Abstract

Bacteria influence site-specific disease etiology and the host’s ability to metabolize xenobiotics, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Lung cancer in Xuanwei, China has been attributed to PAH-rich household air pollution from burning coal. This study seeks to explore the role of lung microbiota in lung cancer among never smoking Xuanwei women and how coal burning may influence these associations. DNA from sputum and buccal samples of never smoking lung cancer cases (n = 8, in duplicate) and controls (n = 8, in duplicate) in two Xuanwei villages was extracted using a multi-step enzymatic and physical lysis, followed by a standardized clean-up. V1–V2 regions of 16S rRNA genes were PCR-amplified. Purified amplicons were sequenced by 454 FLX Titanium pyrosequencing and high-quality sequences were evaluated for diversity and taxonomic membership. Bacterial diversity among cases and controls was similar in buccal samples (P = 0.46), but significantly different in sputum samples (P = 0.038). In sputum, Granulicatella (6.1 vs. 2.0%; P = 0.0016), Abiotrophia (1.5 vs. 0.085%; P = 0.0036), and Streptococcus (40.1 vs. 19.8%; P = 0.0142) were enriched in cases compared with controls. Sputum samples had on average 488.25 species-level OTUs in the flora of cases who used smoky coal (PAHrich) compared with 352.5 OTUs among cases who used smokeless coal (PAH-poor; P = 0.047). These differences were explained by the Bacilli species (Streptococcus infantis and Streptococcus anginosus). Our small study suggests that never smoking lung cancer cases have differing sputum microbiota than controls.

Keywords: lung microbiota, 16S, carcinogenesis, lung cancer, bacteria, respiratory, pulmonary

INTRODUCTION

The bacteria living on and in the human body, collectively described as the microbiota, are ubiquitous and are estimated to outnumber human cells 10-fold [Ley et al., 2006]. Given the vast bacterial communities within the human body and the variety of processes they are involved in, bacteria have substantial influences on health and disease etiology [Hajishengallis et al., 2012]. Bacterial communities have been detected in both lung tissues and bronchoalveolar lavage samples of smokers and nonsmokers [Erb-Downward et al., 2011; Beck et al., 2012; Dickson et al., 2013a,b]. Further, there is evidence to support the hypothesis that bacteria present in the lung play roles in the etiology of nonmalignant respiratory diseases [Lin et al., 2011; Han et al., 2012; Schwabe and Jobin, 2013]. For example, differences in lung bacterial flora have been found between patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and those with nondiseased lungs [Sze et al., 2012]. The potential role of the lung microbiota in lung cancer susceptibility, however, has yet to be defined.

Bacteria have also been shown to influence the host’s ability to metabolize xenobiotics, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) [Van de Wiele et al., 2005]. The human microbiota is the body’s first interface with environmental exposures. In this regard, the lung microbiota may play an important role in the body’s response to known airborne lung carcinogens such as environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) or household coal combustion byproducts [Gao et al., 1988; Lan et al., 2002; Samet et al., 2009; Hosgood et al., 2011]. Household indoor air pollution attributed to coal combustion for heating and cooking increases the levels in the home of known carcinogens, such as PAHs [IARC, 1983; Mumford et al., 1993]. Experimentally, it has been shown that bacteria colonizing humans are capable of metabolizing and detoxifying PAHs [Van de Wiele et al., 2005]; therefore, the lung microbiota may influence the link between household coal exposure and lung cancer risk.

In the study reported here, we aimed to explore the possible impact household air pollution attributed to coal combustion has on the oral and lung microbiota. The Xuanwei region poses a unique opportunity to assess bacterial communities associated with lung cancer risk because this region has the highest female incidence rate of lung cancer in China and a majority of women are never smokers [Mumford et al., 1987; Chapman et al., 1988; Lan and He, 2004]. Nearly all Xuanwei women have substantial exposure to indoor air pollution, which contains PAHs generated by domestic fuel combustion for heating and cooking [Lan et al., 2002; Hosgood et al., 2008], an established lung carcinogen [IARC, 2010]. To this end, we measured the presence of the 16S rRNA genes found in bacteria to assess the microbiota in buccal and sputum samples of never smoking female lung cancer cases and controls from the region of Xuanwei, China.

MATERIALS ANDMETHODS

Study Subjects

For this initial effort, we randomly selected never smoking female lung cancer cases (n = 8) and never smoking female controls (n = 8) from an ongoing case-control study of never smoking females in Xuanwei county, and the neighboring Fuyuan county, China. Cases were women with newly diagnosed primary lung cancer (ICD-9 162) who currently lived in Xuanwei and Fuyuan counties and who were evaluated at one of the 5 study hospitals. The diagnosis of lung cancer was made by histology or cytology. Cases were restricted to those aged 18–79 years of age at the time of diagnosis. Controls were women who had never been diagnosed with lung cancer. Controls were individually matched to cases by age (+/−5 years) and hospital. Controls were selected from never smoking female patients aged 18–79 years old who were evaluated at one of the 5 study hospitals and who were current residents of Xuanwei or Fuyuan counties. The controls were required to have admission diagnoses diseases and conditions that were unrelated to the study’s primary hypotheses regarding household coal exposure and air pollution. Control diseases were drawn from a large, diverse number of categories to ensure that >20% of controls did not have any one condition. The age range of cases and controls selected for this analysis was 45–72 years old. Eligible cases and controls for this analysis were also restricted to those residing in the Laibin and Reshui communities of Xuanwei, which have been shown to have differing risks of lung cancer associated with their respective types of coal burned [Lan et al., 2008]. Residents of Laibin use PAH-rich smoky coal constituting a high risk for lung cancer, while residents of Reshui use smokeless coal, which carries a lower risk for lung cancer. This study was reviewed and approved by the NIH’s Institutional Review board. All subjects provided written, informed consent.

Sample Collection

Buccal samples were collected with two 30-second rinses with water to which isopropanol was immediately added, followed by centrifugation and freezing at −80°C. Sputum samples were collected noninvasively through participant-induced coughing (i.e., without induction) with the expectorate immediately preserved in Saccamono’s fixative. It is well understood that subjects with underlying airway diseases (i.e., COPD, lung cancer) can expectorate sputum spontaneously; however, subjects without underlying airway diseases typically require induction to be able to collect sputum. In this region of China however, subjects can produce sputum without induction. We collected sputum samples from both lung cancer cases and controls using a method (i.e., patient-induced coughing) that was developed and used successfully during a previous case-control study conducted in Xuanwei [Lan et al., 2000]. Cytological examination of sputum collected via this method, specifically from subjects without lung cancer, found that the sputum was derived from the lower respiratory tract and confirmed the presence of bronchial epithelial cells [Keohavong et al., 2005]. Buccal cells and sputum samples were collected from study subjects before surgery or other treatment. Both the sputum and buccal samples for each subject included here were selected in duplicate (i.e., aliquoted from the same parent sample, respectively) for DNA extraction, and 16S PCR amplification and pyrosequencing of the 16S rRNA bacterial genes. Therefore, 32 sputum samples and 32 buccal samples from 16 subjects (two sputum samples and two buccal samples per subject) were included in this study for a total of 64 tested samples.

DNA Extraction

Total genomic DNA was extracted using the protocol described by Zupancic et al. [2012]. Briefly, samples were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 min, after which the supernatant was removed. Cell lysis was initiated by addition of 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline and a first enzymatic cocktail composed of lyzosyme, mutanolysin and lysostaphin. After a 30-min incubation at 37°C, the samples were further lysed by addition of proteinase K and 10% SDS, followed by incubation at 55°C for 45 min. Mechanical disruption was then performed by bead beating using a FP120 FastPrep instrument and 0.1 mm silica spheres. The resulting crude lysate was processed using the ZYMO Fecal DNA kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Negative extraction controls were performed to ensure that the samples were not contaminated by exogenous bacterial DNA during the extraction process.

16S rRNA Gene PCR Amplification and Sequencing

The universal primers 27F and 338R were used for PCR amplification of the V1–V2 hypervariable regions of 16S rRNA genes. The 338R primer included a unique sequence tag to barcode each sample [Zupancic et al., 2012]. Using 96 barcoded 338R primers, the V1–V2 regions of 16S rRNA genes were amplified in 96-well microtiter plates using AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems) and 50 ng of template DNA in a total reaction volume of 25 µl, using the cycling conditions described previously [Zupancic et al., 2012]. Negative controls without a template were included for each barcoded primer pair. PCR products were quantified using the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA assay, and equimolar amounts (100 ng) of the PCR amplicons were mixed in a single tube. The purified amplicon mixture was then sequenced by 454 FLX Titanium pyrosequencing using 454 Life Sciences primer A by the Genomics Resource Center at the Institute for Genome Sciences, University of Maryland School of Medicine, using protocols recommended by the manufacturer as amended by the Center.

Analysis of the16S rRNA Gene Sequences

Reads output by the sequencer were demultiplexed using 5′ barcodes, trimmed of forward and reverse primer sequences, filtered for length and quality, and corrected for homopolymer errors. The resulting high-quality dataset was then screened for chimeric sequences and contaminant chloroplast DNA using UCHIME (de novo mode) [Edgar et al., 2011] and the RDP classifier [Wang et al., 2007], respectively.

Passing sequences were characterized for diversity and taxonomic composition using the QIIME [Caporaso et al., 2010] and R packages. To begin, sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using UCLUST [Edgar, 2010] with a 95% identity threshold. Representative sequences of each cluster were assigned to a taxonomic lineage and used to construct a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree with FastTree. Taxonomic assignment was performed using the RDP classifier (trained by a customized version of the comprehensive GreenGenes 16S database, release v.13-05) with a minimum confidence threshold of 0.80. Alpha and beta-diversity metrics were computed in QIIME. We performed univariate analyses by comparing the abundance of taxonomic groups at all phylogenetic levels (phylum to species) as well as at the OTU level between cases and controls using the nonparametric paired ttest (or Fisher’s exact test for sparse counts) implemented in the Metastats program [White et al., 2009].

RESULTS

Evaluation and Merging of Replicate Data

Of the 32 duplicate pairs included in our analysis, the first 24 (n = 48 total samples) were used for an initial quality control analysis to evaluate the possibility of merging the metadata from biological replicates. We determined the number of shared OTUs under the constraint that an OTU must occur in a given sample with at least 15 sequencing reads (after sub-sampling to 5,000 sequences per sample). For each of the 24 duplicate pairs, we observed that all OTUs shared between the associated duplicates were in 100% concordance, except for one duplicate pair, which had 98.6% concordance. Taxonomic assignments to classes and genera also revealed high correlations with an average Pearson’s correlation coefficient of the relative abundances equal to 0.98 and 0.99, respectively, with an average of 98.9% concordance. Therefore, given the high level of agreement between the duplicates, our analysis plan for the full dataset was to merge the OTU data for each subject’s pair of sputum reads, and merge the OTU data for each subject’s paired buccal reads.

Similarly, we evaluated the overlap between the lung and oral microbiota. The observed OTU abundances among sputum-buccal pairs were not highly correlated, with an average Pearson’s correlation coefficient of the relative abundances equal to 0.54 (range: 0.10–0.86). Therefore, it was planned that microbiota derived from buccal samples and from sputum samples would be analyzed separately in the full dataset as they have unique attributes.

Taxonomic Levels Observed

When all sequencing was completed for all 64 samples included in this study, we obtained a total of 882,578 raw 16S sequences. The loss of sequences due to chimeras was within the expected range (average ~14% of sequences per sample) detected in the entire dataset. The average final read length was 304 base pairs. The average number of reads per sample was 9,351. After excluding two outlier samples, the minimum number of reads per sample was 5,540. The total number of sequences passing this step was 597,386. Sequences passing the preprocessing steps were then merged by biological replicates. We had 31 unique samples, including 16 sputum and 15 buccal samples from eight never smoking lung cancer cases and eight never smoking controls.

The total counts of 16S sequences associated with each taxon are summarized in supplemental materials for Phylum (Supporting Information Table SI) Class (Supporting Information Table SII), Order (Supporting Information Table SIII), Family (Supporting Information Table SIV), and Genus (Supporting Information Table SV). In general, the oral communities were dominated at the Phylum level by Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Fusobacteria members (Fig. 1a). When compared with the sputum samples, we observed a clear dominance of Bacilli in buccal samples, and a potential enrichment of Fusobacteria and Bacteroidia in the sputum samples relative to buccal communities (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Class level distributions of sequences from (A) buccal and (B) sputum samples from never smoking female lung cancer cases and never smoking female controls in Xuanwei, China. Samples are organized by case status (cancer case or control).

Oral Microbiota Derived from Buccal Samples

A total of 3,222 OTUs were used to calculate Alphadiversity metrics (i.e., Chao1 estimator, Shannon entropy, the reciprocal Simpson index). We observed on average 520.75 species-level OTUs in the oral flora of controls, compared with 469.125 species among cases (P = 0.33). Overall, oral bacterial community diversity was similar between cases and controls (Chao1 estimator P = 0.46; Shannon entropy P = 0.13; reciprocal Simpson index P = 0.27). We found limited evidence of reduced levels of four particular family level taxa in the oral microbiata of lung cancer patients (Odoribacteraceae, a subgroup of uncharacterized Gammaproteobacteria, Dethiosulfovibrionaceae, an uncharacterized subgroup of Firmicutes; Supporting Information Table SVI).

When stratifying these results by coal type, the average number of species-level OTUs between the oral microbiota of controls from Laibin (n = 526.5) and Reshui (n = 515.0) were statistically similar (P = 0.82). No differences were observed between specific Phyla, Class, or Order identified from buccal samples in the two villages (metastats P > 0.05; Supporting Information Table SVIII). At the Family level, there was a suggestion that a rare Burkholderiales subgroup (<0.01% on average in each community) is slightly enriched in Laibin controls (metastats P = 0.001). Similarly, the average number of species-level OTUs were similar for the oral microbiata of cases in the two villages (Laibin: n = 511.25; Reshui: n = 427.0; P = 0.40). Clear differences were not observed between specific Phyla, Class, Order, or Families identified from buccal samples collected from cases in the two villages (metastats P > 0.05; Supporting Information Table SIX).

Lung Microbiota Derived from Sputum Samples

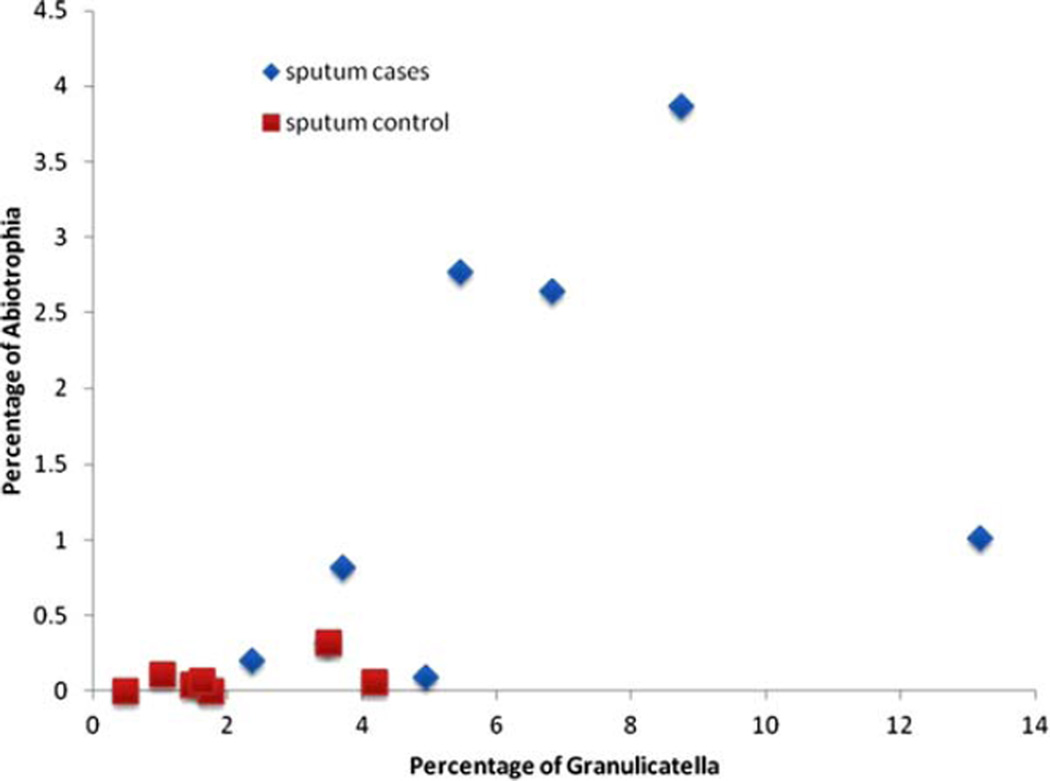

An average of 420.5 species-level OTUs were observed in the lung microbiota of cases and 473.0 in controls (P = 0.28). Differences in bacterial communities were evident when comparing sputum samples in lung cancer cases and healthy controls (Chao1 estimator P = 0.038; Shannon entropy P = 0.058; reciprocal Simpson index P = 0.10). Evidence of multiple genus-level differences among cancer cases and controls was observed (Table I; Supporting Information Table SVII). Lung cancer cases had an enrichment of Granulicatella (6.1 vs. 2.0%; P = 0.0016), Abiotrophia (1.5 vs. 0.085%; P = 0.0036), and Streptococcus (40.1 vs. 19.8%; P = 0.0142) members relative to controls (Fig. 2).

TABLE I.

Differentially Abundant Genera Between Sputum Communities in Never Smoking Female Lung Cancer Cases and Never Smoking Female Controls in Xuanwei, China

| Average % Abundance | P-values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic lineage | Cases | Controls | Metastats | Mann-Whitney | Fisher’s |

| Lactobacillales; Carnobacteriaceae; Granulicatella | 6.1 | 2 | 0.0016 | 0.0059 | 0 |

| Synechococcales; Synechococcaceae; Synechococcus | 0 | 0.0083 | 0.0027 | 0.0069 | 0.0022 |

| Lactobacillales; Aerococcaceae; Abiotrophia | 1.5 | 0.085 | 0.0036 | 0.0053 | 2.11E-264 |

| Sphingomonadaceae; Sphingomonas | 0 | 0.037 | 0.0062 | 0.0071 | 1.21E-12 |

| Betaproteobacteria; Burkholderiales; Other | 0.005 | 0.034 | 0.0078 | 0.0077 | 1.20E-06 |

| Oxalobacteraceae; Polynucleobacter | 0 | 0.006 | 0.0103 | 0.0205 | 0.0103 |

| Lactobacillales; Streptococcaceae; Streptococcus | 40.1 | 19.8 | 0.0142 | 0.054 | 0 |

| Bacteroidetes; Cytophagaceae; Hymenobacter | 0 | 0.007 | 0.0145 | 0.0211 | 0.0048 |

| Fusobacteria; Leptotrichiaceae; Leptotrichia | 0.6 | 5.4 | 0.0207 | 0.0401 | 0 |

Fig. 2.

Genus trends for the percentage of Abiotrophia and Granulicatella associated with cancer status, among never smoking female lung cancer cases and never smoking female controls in Xuanwei, China. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Principal coordinate analysis using the unweighted Unifrac distance metric found that the sputum samples from lung cancer cases appeared much closer to each other than the sputum samples from controls (Fig. 3). Using the quantitative UniFrac distances, the sputum cancer samples were significantly closer to each other than they were to the sputum control samples (P = 0.002; Mann-Whitney test).

Fig. 3.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plot of sputum samples from never smoking female lung cancer cases and never smoking female controls in Xuanwei, China [PCoA plot is based on the unweighted Unifrac distance metric. We see an apparent clustering based on cancer status that is statistically significant (P = 0.002)]. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Analyses were then stratified by coal type and case and control status. Among controls, no differences were observed for the lung microbiota in terms of the average number of species-level OTUs (Laibin: n = 499.0; Reshui: n = 453.5; P = 0.49), nor between specific Phyla, Class, Order, or Families identified from sputum samples in the two villages (Supporting Information Table SX). However, we observed on average 488.25 species-level OTUs in the sputum of cases from Laibin, compared with 352.5 for cases in Reshui (P = 0.047). At the Phylum level, Proteobacteria was significantly enriched in the Reshui cases (17.6 vs. 4.0%; metastats P = 0.015; Supporting Information Table SXI). Proceeding deeper into the phylogeny of these assignments, the Proteobacteria difference can be largely attributed to members of the Neisseria genus, which are significantly enriched in Reshui lung cancer cases (metastats P = 0.01). Additionally, two genus-level subgroups of Bacilli were significantly enriched in the Laibin sputum lung cancer samples; however, these two groups could not be classified to a particular genus. Two species-level OTUs from the genus Streptococcus (tentatively assigned to S. infantis and S. anginosus) showed evidence of enrichment in the Laibin samples, while a Neisseria species-level OTU was found to drive the enrichment in Reshui sputum cases (15.3 vs. 2.6%).

DISCUSSION

The lung microbiota may have implications for lung cancer etiology. While there is a suggestive body of literature to support this hypothesis, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of differences among the lung flora of lung cancer cases and controls. Our study demonstrates the presence of oral (buccal samples) and lung (sputum samples) microbiota among never smoking subjects with and without lung cancer. Even more importantly, our results suggest that the oral microbiota can be differentiated from that of the respiratory tract, with bacterial species unique to the sputum and not due to contamination by the oral mucosa during sputum collection. We report the presence of a lung microbiota in sputum samples of never smoking lung cancer cases and never smoking controls that is unique from the oral microbiota in paired buccal samples. Further, we observed bacterial composition differences in the sputum of cases, associated with the coal type burned in the homes of the subjects. Juxtaposing these discoveries with our findings that specific taxonomic groups are more often present in lung cancer cases than controls, our initial study provides evidence that bacterial community composition in the lung, when using sputum as a surrogate, may be associated with lung cancer attributed to solid fuel use.

The most notable differences observed between cases and controls was the enrichment for OTUs belonging to Granulicatella, Abiotrophia, and Streptococcus among the sputum of the cases. Interestingly, Granulicatella has been previously identified as part of the normal flora of the respiratory tract [Harris et al., 2007], and is being increasing implicated in clinically relevant infections leading to central nervous system infections, sinusitis, and other infections [Michelow et al., 2000; Hepburn et al., 2003; De Luca et al., 2013]. Abiotrophia has been associated with aortitis [Raff et al., 2004]. Streptococcus is causally linked to the chronic lung disease pneumonia [van der Poll and Opal]. A recent systematic review of the risk of lung cancer associated with history of lung diseases found elevated risks associated with COPD, chronic bronchitis, and tuberculosis (TB) [Brenner et al., 2011]. Interestingly, pneumonia was associated with lung cancer among never smokers [Brenner et al., 2011]. The associations between nonmalignant lung diseases, specifically TB, COPD, and chronic bronchitis, and the risk of lung cancer have also been reported in Xuanwei, China [Hosgood et al., 2013]. This suggests that the etiologic link between the pathogens enriched in our cases (i.e., Granulicatella, Streptococcus) and lung cancer is potentially driven by chronic inflammation of the lung. In support of this hypothesis, microbes have tremendous influence on how our organs respond to immunologic challenges as they effect innate immune responses and immune homeostasis [Garn et al., 2013]. Presumably the regulatory pathways of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) are heavily involved in this mechanism [Elinav et al., 2013]; however, more research focusing specifically on the respiratory tract is needed. One such hypothesis to test would be to explore if degradation of the mucosal barrier promotes inflammation and carcinogenesis, or if the relationship occurs in reverse, or potentially even in both directions [Schwabe and Jobin, 2013].

Although microbiota differences between cases and controls provides new etiologic clues for lung cancer, the risk of lung cancer in Xuanwei is primarily driven by household air pollution attributed to coal burning for heating and cooking. Therefore, it is the interaction between coal smoke and microbiota that is of particular interest to elucidate the underlying mechanism of lung cancer in Xuanwei. Microbiota may play an important role in how the host interacts with environmental exposures [Kostic et al., 2013]. Bacteria within the respiratory tract can be viewed as the first point of contact with the inhalable environment. Microbiota may influence the body’s ability to process and respond to environmental exposures, and environmental conditions can influence the microbiota’s composition and function [Backhed, 2012]. Specifically, the lung microbiota may play an important role in response to known airborne lung carcinogens in household coal combustion byproducts, such as PAHs [IARC, 1983; Mumford et al., 1993]. Using a human intestinal microbial ecosystem (SHIME), researchers have Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis. DOI 10.1002/em 6 Hosgood et al. mimicked the human colon [Zhong et al., 2000]. After inoculation, the microbiota in the SHIME reached a steady state, were sequenced, and were found to be dominated by Bacteroidetes [Zhong et al., 2000]. PAHs were then introduced into the SHIME and the system successfully metabolized PAHs [Wu et al., 2009]. The microbiota of our study population are also enriched for Bacteroidetes like the SHIME. Therefore, it has been shown experimentally that bacteria colonizing humans, and specifically bacteria that have been found in the oral and lung microbiota of our study population, are capable of metabolizing and detoxifying PAHs [Van de Wiele et al., 2005]; therefore, the lung microbiota may influence the link between household air pollution and lung cancer risk through a microbiota-household air pollution interaction. Although our study is under powered to formally test this interaction, the results support our hypothesis given that the mean bacterial abundance of Bacteroidetes found in the sputum of lung cancer cases from Laibin was only 2.6%, compared with 14.6% for Reshui cases, 20.8% for Laibin controls, and 20.7% for Reshui controls.

The major strength of our study is the novel hypothesis, and the fact that this is the first project to report on the lung microbiota and lung cancer. Our unique study population is also a major strength. Our population of women from Xuanwei has the highest incidence rate of lung cancer in China [Lan and He, 2004]. The similar lung cancer rates in Xuanwei men and women is of interest, because almost all women in this area are nonsmokers [Mumford et al., 1987; Chapman et al., 1988; He et al., 1991], suggesting that either environmental factors, or genetic factors not related to tobacco smoke, may be driving the increased risk. Further supporting this hypothesis, nearly all Xuanwei women and few men cook, while most men and nearly no women smoke tobacco [Chapman et al., 1988]. While coal, other environmental exposures (i.e., ETS), genetic variation, and TB infection have been associated with lung cancer in this population [Lan et al., 2000, 2002; Hosgood et al., 2008; Engels et al., 2009], these associations do not collectively account for the high lung cancer burden in this unique population. For this first analysis, we focused on the unique population of Xuanwei and used only never smokers to minimize confounding from active tobacco smoking. While this is strength for this study, this may limit the generalizability of our results to smoking populations since the molecular pathogenesis of lung cancer differs by smoking status. From a public health standpoint though, lung cancer in nonsmokers remains a concern as it is the sixth leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States, ahead of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and cancers of the liver, ovaries, bladder, brain, and kidneys [Rudin et al., 2009].

There are limitations associated with our results that must be considered. First, since we used a case-control study design, we were unable to eliminate the possibility that our observed differences may have been influenced by reverse causation. Although reverse causation cannot be completely overcome in a case-control design, it is useful to demonstrate case-control differences in the lung microbiota prior to seeking the use of precious, prospectively collected and stored biological samples from existing cohort studies. Further, the 16S-based sequencing assay does not differentiate between viable and nonviable bacteria. Our results have identified microbial communities in the lung; however, we are not able to determine if our observed perturbations are attributed to living, metabolically active bacterial cells or dead, lysed cells that are in the process of being eliminated by the lung’s clearance mechanism. In addition, we have only evaluated the microbiota at a single time point. Therefore, we are observing bacteria in a given environmental “snapshot”, which does not mean that these bacteria are stable residents in this environment. Additionally, we used noninduced sputum, which many may come from differing parts of the lung of a subject based on exposure levels. Finally, given our limited sample size, we were unable to explore histology-specific results. Therefore, more research is needed to determine if our observed microbiota differences in cases from Reshui compared with cases from Laibin are fully attributed to the differences in coal type used or if prevalence differences in lung cancer subtype diagnosed in the two villages may explain the results. A preliminary analysis of our previous cohort study [Lan et al., 2002] found the percentages of lung cancer cases being diagnosed as adenocarcinomas and as squamous cell carcinomas were similar in Reshui compared with Laibin.

Even with these caveats, as well as issues related to multiple comparisons, our findings provide the critical first step of identifying if bacterial communities are differentially present in the cancerous lung relative to the noncancerous lung. Although our findings are early and must be replicated in larger sample sizes, they highlight the need for further research related to the role of bacterial communities in respiratory health and respiratory diseases, potentially leading to a novel field of research related to the role that pathogens play in the lung. A larger sample size would enable a more detailed analysis of the differences we observed between cases, particularly by histology, who use smoky coal compared to cases who use smokeless coal. Research should also explore the role of coal constituents in addition to PAHs. For example, coal found in the Southwest Guizhou region of China has high arsenic content [Liu et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2007]. Future studies replicating our findings, particularly among prospectively collected serial samples, will have clinical and translational importance given that antimicrobial regimens have been identified for the treatment of the microbes we found enriched among cases [Ruoff, 1991].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: The Intramural National Cancer Institute; Grant number: N01-CO-12400.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Conflicts of interest: None to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

HDH, NR, and QL designed the study. WH, JX, RV, XH, GW, FW, HDH, NR, and QL carried out the Xuanwei case-control study. ARS, JRW, and EFM carried out the sequencing and initial data analyses. HDH, NR, TR, RV, ARS, JRW, EFM, and QL took part in interpretation of results and manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

- Backhed F. Host responses to the human microbiome. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(Suppl 1):S14–S17. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JM, Young VB, Huffnagle GB. The microbiome of the lung. Transl Res. 2012;160:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner DR, McLaughlin JR, Hung RJ. Previous lung diseases and lung cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RS, Mumford JL, Harris DB, He ZZ, Jiang WZ, Yang RD. The epidemiology of lung cancer in Xuan Wei, China: Current progress, issues, and research strategies. Arch Environ Health. 1988;43:180–185. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1988.9935850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JG, Chen YG, Zhou YS, Lin GF, Li XJ, Jia CG, Guo WC, Du H, Lu HC, Meng H, et al. A follow-up study of mortality among the arseniasis patients exposed to indoor combustion of high arsenic coal in Southwest Guizhou Autonomous Prefecture, China. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2007;81:9–17. doi: 10.1007/s00420-007-0187-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca M, Amodio D, Chiurchiu S, Castelluzzo MA, Rinelli G, Bernaschi P, Calo Carducci FI, D’Argenio P. Granulicatella bacteraemia in children: two cases and review of the literature. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson RP, Erb-Downward JR, Huffnagle GB. The role of the bacterial microbiome in lung disease. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2013a;7:245–257. doi: 10.1586/ers.13.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson RP, Huang YJ, Martinez FJ, Huffnagle GB. The lung microbiome and viral-induced exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: New observations, novel approaches. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013b;188:1185–1186. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1573ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinav E, Nowarski R, Thaiss CA, Hu B, Jin C, Flavell RA. Inflammation-induced cancer: Crosstalk between tumours, immune cells and microorganisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:759–771. doi: 10.1038/nrc3611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels EA, Shen M, Chapman RS, Pfeiffer RM, Yu YY, He X, Lan Q. Tuberculosis and subsequent risk of lung cancer in Xuanwei, China. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1183–1187. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb-Downward JR, Thompson DL, Han MK, Freeman CM, McCloskey L, Schmidt LA, Young VB, Toews GB, Curtis JL, Sundaram B, et al. Analysis of the lung microbiome in the "healthy" smoker and in COPD. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao YT, Blot WJ, Zheng W, Fraumeni JF, Hsu CW. Lung cancer and smoking in Shanghai. Int J Epidemiol. 1988;17:277–280. doi: 10.1093/ije/17.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garn H, Neves JF, Blumberg RS, Renz H. Effect of barrier microbes on organ-based inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1465–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP, Curtis MA. The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:717–725. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han MK, Huang YJ, Lipuma JJ, Boushey HA, Boucher RC, Cookson WO, Curtis JL, Erb-Downward J, Lynch SV, Sethi S, et al. Significance of the microbiome in obstructive lung disease. Thorax. 2012;67:456–463. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JK, De Groote MA, Sagel SD, Zemanick ET, Kapsner R, Penvari C, Kaess H, Deterding RR, Accurso FJ, Pace NR. Molecular identification of bacteria in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from children with cystic fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20529–20533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709804104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XZ, Chen W, Liu ZY, Chapman RS. An epidemiological study of lung cancer in Xuan Wei County, China: current progress. Case-control study on lung cancer and cooking fuel. Environ Health Perspect. 1991;94:9–13. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94-1567943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn MJ, Fraser SL, Rennie TA, Singleton CM, Delgado B., Jr Septic arthritis caused by Granulicatella adiacens: diagnosis by inoculation of synovial fluid into blood culture bottles. Rheumatol Int. 2003;23(5):255–257. doi: 10.1007/s00296-003-0305-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosgood HD, III, Wei H, Sapkota A, Choudhury I, Bruce N, Smith KR, Rothman N, Lan Q. Household coal use and lung cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies, with an emphasis on geographic variation. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:719–728. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosgood HD, Chapman R, Shen M, Blair A, Chen E, Zheng T, Lee KM, He X, Lan Q. Portable stove use is associated with lower lung cancer mortality risk in lifetime smoky coal users. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1934–1939. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosgood HD, Chapman RS, He X, Hu W, Tian L, Liu LZ, Lai H, Chen W, Rothman N, Lan Q. History of lung disease and risk of lung cancer in a population with high household fuel combustion exposures in rural China. Lung Cancer. 2013;81:343–346. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humans IMotEotCRt, editor. IARC. Polynuclear aromatic compounds. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer Monographs on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Humans IMotEotCRt, editor. IARC. Household Use of Solid Fuels and High-temperature Frying. Lyon: World Health Organization; 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keohavong P, Lan Q, Gao WM, Zheng KC, Mady HH, Melhem MF, Mumford JL. Detection of p53 and K-ras mutations in sputum of individuals exposed to smoky coal emissions in Xuan Wei County, China. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:303–308. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostic AD, Howitt MR, Garrett WS. Exploring host-microbiota interactions in animal models and humans. Genes Dev. 2013;27:701–718. doi: 10.1101/gad.212522.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Q, He X, Costa DJ, Tian L, Rothman N, Hu G, Mumford JL. Indoor coal combustion emissions, GSTM1 and GSTT1 genotypes, and lung cancer risk: A case-control study in Xuan Wei, China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:605–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Q, He XZ. Molecular epidemiological studies on the relationship between indoor coal burning and lung cancer in Xuan Wei, China. Toxicology. 2004;198:301–305. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Q, Chapman RS, Schreinemachers DM, Tian L, He X. Household stove improvement and risk of lung cancer in Xuanwei, China. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:826–835. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.11.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Q, He X, Shen M, Tian L, Liu LZ, Lai H, Chen W, Berndt SI, Hosgood HD, Lee KM, et al. Variation in lung cancer risk by smoky coal subtype in Xuanwei, China. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2164–2169. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley RE, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Ecological and evolutionary forces shaping microbial diversity in the human intestine. Cell. 2006;124:837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin KW, Li J, Finn PW. Emerging pathways in asthma: Innate and adaptive interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1810:1052–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zheng B, Aposhian HV, Zhou Y, Chen ML, Zhang A, Waalkes MP. Chronic arsenic poisoning from burning high-arsenic-containing coal in Guizhou, China. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:119–122. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelow IC, McCracken GH, Jr, Luckett PM, Krisher K. Abiotrophia spp. brain abscess in a child with Down’s syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:760–763. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200008000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumford JL, He XZ, Chapman RS, Cao SR, Harris DB, Li XM, Xian YL, Jiang WZ, Xu CW, Chuang JC, et al. Lung cancer and indoor air pollution in Xuan Wei, China. Science. 1987;235:217–220. doi: 10.1126/science.3798109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumford JL, Lee XM, Lewtas J, Young TL, Santella RM. DNA adducts as biomarkers for assessing exposure to polycyclic aromatic-hydrocarbons in tissues from Xuan-Wei women with high exposure to coal combustion emissions and high lung-cancer mortality. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;99:83–87. doi: 10.1289/ehp.939983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raff GW, Gray BM, Torres A, Jr, Hasselman TE. Aortitis in a child with Abiotrophia defectiva endocarditis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:574–576. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000130077.41121.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudin CM, Avila-Tang E, Harris CC, Herman JG, Hirsch FR, Pao W, Schwartz AG, Vahakangas KH, Samet JM. Lung cancer in never smokers: molecular profiles and therapeutic implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5646–5661. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruoff KL. Nutritionally variant streptococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:184–190. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.2.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet JM, Avila-Tang E, Boffetta P, Hannan LM, Olivo-Marston S, Thun MJ, Rudin CM. Lung cancer in never smokers: Clinical epidemiology and environmental risk factors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5626–5645. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe RF, Jobin C. The microbiome and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:800–812. doi: 10.1038/nrc3610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze MA, Dimitriu PA, Hayashi S, Elliott WM, McDonough JE, Gosselink JV, Cooper J, Sin DD, Mohn WW, Hogg JC. The lung tissue microbiome in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1073–1080. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2075OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Wiele T, Vanhaecke L, Boeckaert C, Peru K, Headley J, Verstraete W, Siciliano S. Human colon microbiota transform polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to estrogenic metabolites. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:6–10. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Poll T, Opal SM. Pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention of pneumococcal pneumonia. Lancet. 2009;374:1543–1556. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JR, Nagarajan N, Pop M. Statistical methods for detecting differentially abundant features in clinical metagenomic samples. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Hu Z, Yu D, Huang L, Jin G, Liang J, Guo H, Tan W, Zhang M, Qian J, et al. Genetic variants on chromosome 15q25 associated with lung cancer risk in Chinese populations. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5065–5072. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L, Goldberg MS, Parent ME, Hanley JA. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and the risk of lung cancer: A metaanalysis. Lung Cancer. 2000;27:3–18. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(99)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zupancic ML, Cantarel BL, Liu Z, Drabek EF, Ryan KA, Cirimotich S, Jones C, Knight R, Walters WA, Knights D, et al. Analysis of the gut microbiota in the old order Amish and its relation to the metabolic syndrome. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.