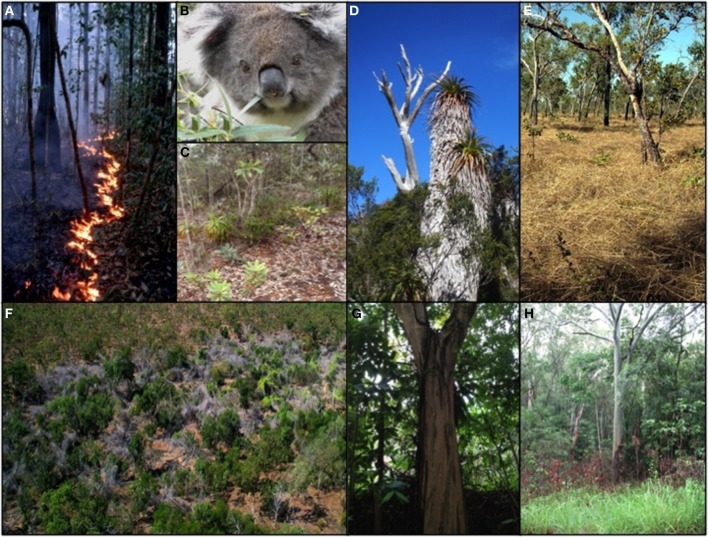

Figure 1.

Diverse plant traits that affect vegetation flammability. (A) Surface fire in Amazonian rainforest leaf litter and ground cover vegetation during a severe drought, when leaf moisture context of living and dead foliage was very low (Photo: Mark Cochrane); (B) Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus), an iconic specialist mammalian herbivore involved in a co-evolutionary relationship with eucalypt leaf secondary chemical defenses. These defenses also make foliage exceptionally flammable (Photo Kath Handasyde); (C) New Caledonian maquis vegetation, which is dominated by sclerophyll species with phylogenetic links to Australian flammable heathland, yet has a poor capacity to recover from fire (Photo David Bowman); (D) leaf retention of Richea pandanifolius, a fire sensitive Gondwana rainforest giant heath, demonstrates that this trait is not universally associated with increasing flammability (Photo David Bowman); (E) low bulk density annual grass layer in eucalypt savanna is exceptionally flammable (Photo Don Franklin); (F) post-flowering die-off of the giant bamboo Bambusa arnhemica in frequently burnt eucalypt savanna. The dead bamboo is much less flammable than the grass layer in surrounding savanna (photo Don Franklin); (G) decorticating bark on a SE Asian tropical rainforest tree Cratoxylum cochinchinense demonstrates that this trait is not necessarily related to spreading fires via fire brands (Photo David Tng); (H) abrupt rain forest boundary in north Queensland which limits the spread of savanna fires, as evidenced by the shrubs burnt in the preceding dry season (Photo David Bowman).