Abstract

Depression and other health problems are common co-morbidities among persons living with human immunodeficiency virus infection/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS). The aim of this study was to investigate depression, health status, and substance use in relation to HIV-infected and uninfected individuals in South Africa. Using a cross-sectional case-control design, we compared depression, physical health, mental health, problem alcohol use, and tobacco use in a sample of HIV infected (N=143) and HIV uninfected (N=199) respondents who had known their HIV status for two months. We found that depression was higher and physical health and mental health were lower in HIV positive than HIV negative individuals. Poor physical health also moderated the effect of HIV infection on depression; HIV positive individuals were significantly more depressed than HIV negative controls, but only when general physical health was also poor. We did not find an association between alcohol or tobacco use and HIV status. These results suggest the importance of incorporating the management of psychological health in the treatment of HIV.

Keywords: Co-morbidity, Depression, Physical health, Mental Health, HIV status, South Africa

Introduction

Depression and other mental health issues are common co-morbidities in human immunodeficiency virus infection/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), but the literature is mostly from developed countries (Ciesla & Roberts, 2001; Judd et al., 2005). Studies from developing countries, especially Africa, are fairly limited, in terms of (1) the number of such studies (see reviews by Brandt 2009 and Breuer, Myer, Struthers & Joska, 2011), (2) the frequent lack of a proper HIV negative control group, (3) the assessment of mental health in respondents unaware of their HIV status, and (4) the paucity of research on substance use and HIV.

While HIV's neurotropic effect may directly cause mental health co-morbidities (Judd et al., 2005), psychological adjustment after one becomes aware of one's HIV status may have stronger effect (Chikezie, Otakpor, Kuteyi & James, 2013). Some studies have found no association between HIV and depression in individuals unaware of their HIV status (e.g., Rochat et al., 2006; Mfusi & Mahabeer, 2000; Carson, Sandler, Owino, Matete, & Johnstone, 1998), but others where respondents did know their HIV status found a significant association (Adewuya et al., 2007; Shisana et al., 2005; Sebit et al., 2003; Maj et al., 1994; Lindner 2006; Brandt 2007; Chikezie et al., 2013). Finally, although alcohol use disorders (Boden & Fergusson, 2011; Sullivan, Goulet, Justice & Fiellin, 2011) and smoking/nicotine dependence (Tsuang, Francis, Minor, Thomas & Stone, 2012) are associated with depression, the relationship between HIV and substance use is under-researched. The aim of our study was, thus, to investigate the relationship between HIV and depression, health status, and substance use in South Africa, comparing HIV-infected individuals to HIV-uninfected controls, two months after the respondents received their HIV diagnosis. Studying depression in PLWHA is important given depression's effect on immune functioning (Cruess et al., 2003) and ART non-adherence (Nakimuli-Mpungu et al., 2013).

Method

Study design

This was a cross-sectional case–control study of HIV positive clients and randomly slected unmatched HIV negative clients (≥18 years of age), both concurrently enrolled post-HIV testing.

Study setting

The study was conducted in public primary care health facilities in Nkangala district, Mpumalanga province, South Africa. The antenatal HIV prevalence rate in Nkangala district was 32.1% in 2012 (29.5% national) (Department of Health, 2014). In a study in HIV testing sites in Mpumalanga province, the proportion of men were 33.6% and women 66.4%; the HIV prevalence did not significantly differ between men and women in the clients from these HIV testing sites (Peltzer, 2012).

Participants

Participants (N=342) were recruited from a systematic sample of consecutive post-HIV testing clients between September 2009 and April 2010. Every HIV positive respondent and every third HIV negative respondent was recruited as ‘case’ and ‘control’ respectively, resulting in almost a 1:1 ratio of HIV positive to HIV negative clients. Participation in our study took place two months after the participants' HIV diagnosis, and, due to higher attrition of HIV+ clients, 60% of our sample was HIV negative. Data were collected by face-to-face interviews performed in Zulu (the language of the respondents); the questionnaire was translated from English to Zulu and back translated for consistency (Szrek, Chao, Ramlagan, & Peltzer, 2012). The study was approved by the Human Sciences Research Council Ethics Committee.

Participants (N=342) were a subsample of respondents referred from another study that took place in health clinics around Witbank in Mpumalanga province, South Africa. The other study recruited a systematic sample of consecutive post-HIV testing clients who visited the study clinics during a five-month period. Every HIV positive respondent and every third HIV negative respondent was recruited, resulting in a sample with almost a 1:1 ratio of HIV positive to HIV negative clients. Participation in our study took place two months after the participants' HIV tests, and, due to higher attrition of HIV+ clients, 60% of our sample was HIV negative. After informed consent participants were interviewed with a questionnaire. The questionnaire was translated from English to the study languages (Northern Sotho and Zulu) and back translated. Participants were reimbursed travel expenses. Data were collected between September 2009 and April 2010 (Szrek, Chao, Ramlagan, & Peltzer, 2012). The study was approved by the Human Sciences Research Council Ethics Committee.

Measures

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 10-item version of the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994). Scoring is classified from 0 to 9, 10 to 14, and 15 or higher as mild, moderate, and severe depressive symptoms, respectively (Kilbourne et al., 2002). The Cronbach alpha of this 10-item scale was 0.71 in this study.

Alcohol use was assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT-C) questionnaire (Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn & Bradley, 1998), a measure of consumption of alcohol (i.e., the frequency of drinking, the quantity consumed at a typical occasion), and the frequency of heavy episodic drinking (5 drinks for men and 4 for women). Hazardous or harmful or dependent drinking was defined by using an AUDIT-C cutoff score of 4 for men and 3 for women (Bush et al., 1998). The Cronbach alpha of AUDIT-C for this study was 0.91.

Tobacco use was measured by asking, “Do you currently use one or more of the following tobacco products (cigarettes, snuff, chewing tobacco, cigars, etc.)?” Response options were ‘yes’ or ‘no’ (WHO, 1998).

General health

The Short Form (SF)-12v2 scoring algorithm was used to generate Physical Component (PCS-12) and Mental Component (MCS-12) scores, with lower scores indicating lower health (Ware et al., 1995).

Socio-demographic variables included age, sex, education, marital status, household income and household wealth (including household possessions, having electricity or tap water in the house, and formal versus shack dwelling).

Statistical Methods

We calculated summary statistics for the demographic and health variables, tested for differences between HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups using chi-square for discrete variables and Wilcoxon ranksum for continuous variables. As recruitment was based only on HIV status, we control for other variables using regression. We used ordinary least squares for continuous dependent variables and ordinal logistic regression for the CES-D cutoffs (low, moderate, and severe depression). Stata 13 was used for the analysis.

Results

For the overall sample of 342, 214 (62.6%) were female and 128 (37.4%) male, and 143 (41.8%) were HIV-infected and 199 (58.2%) were uninfected (see Table 1). Relative to the HIV-uninfected control group, HIV-infected respondents were significantly more likely to be female, between the ages of 30-44, and severely depressed. In fact, 22% of HIV-infected respondents (compared to 13% of controls) were screened positive for severe depression. PCS12 and MCS12 scores were lower among the HIV-infected group. Hazardous or harmful or dependent alcohol use and current tobacco use were not related to HIV status.

Table 1. Comparison between HIV-positive and control (HIV-negative) groups, by demographic and health variables.

| HIV Positive Group | HIV negative control group | Statistical tests of difference between groups | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=143 (%) | N=199 (%) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 101 (70.6) | 113 (56.8) | chi2 = 6.81, df = 1, p < .01 |

| Male | 42 (29.4) | 86 (43.3) | |

| Age group | |||

| 18-29 yrs | 57 (39.9) | 112 (56.3) | chi2 = 10.60, df = 1, p < .01 |

| 30-44 | 71 (49.7) | 65 (32.7) | |

| 45+ | 15 (10.5) | 22 (11.1) | |

| Level of education | |||

| None/some/primary | 25 (17.5) | 29 (14.6) | chi2 = 3.48, df = 2, p = 0.18 |

| Some/secondary | 100 (69.9) | 130 (65.3) | |

| Postsecondary | 18 (12.6) | 40 (20.1) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 72 (50.4) | 115 (57.8) | chi2 = 2.29, df = 2, p = 0.32 |

| Married/cohabiting | 60 (42.0) | 74 (37.2) | |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 11 (7.7) | 10 (5.0) | |

| Hazardous or harmful or dependent alcohol use | 31 (21.7) | 48 (24.1) | chi2 = 0.28, df = 1, p = 0.60 |

| Current tobacco use | 26 (18.2) | 41 (15.6) | chi2 = 0.41, df = 1, p = 0.52 |

| Depression (CESD score) | |||

| Low (0-9) | 62 (43.4) | 115 (57.8) | chi2 = 8.72, df = 2, p < 0.05 |

| Moderate (10-14) | 49 (34.3) | 59 (29.7) | |

| Severe (15+) | 32 (22.4) | 25 (12.6) | |

|

| |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

|

| |||

| Depression score | 10.6 (5.5) | 8.9 (5.0) | Wilcoxon z = 3.05, p < 0.01 |

| PCS12 (physical health)1 | 45.4 (10.5) | 48.5 (9.1) | Wilcoxon z = 2.78, p < 0.01 |

| MCS12 (mental health) 1 | 44.7 (11.5) | 48.2 (10.1) | Wilcoxon z = 3.00, p < 0.01 |

PCS12 = physical component summary score; MCS12 = mental component summary score

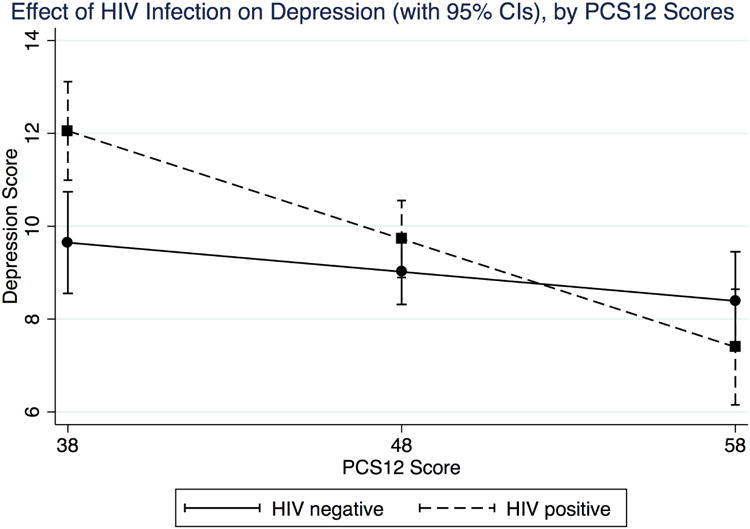

Table 2 presents multivariate regression results with HIV status as a determinant of poor health outcomes, controlling for demographic covariates. Columns 1, 2, and 3 present ordinary least squares regressions using PCS12, MCS12, and CES-D 10-item scores as the dependent variable. HIV infected respondents had statistically significantly lower physical and mental health scores, as well as higher depression scores, even when income and wealth variables were added as covariates (not shown in the tables, but available from authors upon request). Because poorer health may moderate the effect of HIV infection on depression, we ran a regression interacting PCS12 and HIV. Figure 1 shows the effect of HIV on depression at different levels of PCS12. HIV infected participants were more depressed than HIV uninfected controls but only when physical health (PCS12) was also lower than average.

Table 2. Regression of health outcome variables on socio-demographic variables.

| Least Squares Regressions | Ordinal Logistic Regression | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PCS12 | MCS12 | CES-D 10-item | CES-D 3 levels | ||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

| Coefficient [s.e.] | Odds ratio [95% CI] | ||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

| HIV infected (vs. HIV negative) | -2.69 | [1.08]* * | -3.10 | [1.21]* * | 1.34 | [0.59]* * | 1.62 | [1.04 - 2.50]* * | |

| Male (vs. Female) | 1.14 | [1.07] | -0.06 | [1.16] | -0.51 | [0.59] | 0.71 | [0.44 - 1.13] | |

| Age groups (vs. 18-29) | |||||||||

| 30-44 | -0.77 | [1.21] | 0.71 | [1.39] | 0.47 | [0.63] | 1.07 | [0.63 - 1.80] | |

| 45+ | -4.69 | [1.98]* * | 3.62 | [2.44] | 0.66 | [1.31] | 1.19 | [0.52 - 2.72] | |

| Educational Level (vs. None/Some/Primary) | |||||||||

| Some/secondary | 4.11 | [1.71]* * | 5.05 | [1.93]*** | -1.76 | [1.02]* | 0.62 | [0.29 - 1.33] | |

| Postsecondary | 6.07 | [1.90]*** | 9.91 | [2.19]*** | -3.73 | [1.14]*** | 0.17 | [0.07 - 0.47]*** | |

| Marital Status (vs. Single) | |||||||||

| Married/cohabiting | 0.46 | [1.16] | 1.38 | [1.35] | -0.33 | [0.62] | 1.10 | [0.68 - 1.77] | |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 1.66 | [2.43] | -1.62 | [2.85] | 0.88 | [1.28] | 1.66 | [0.75 - 3.68] | |

| Intercept | 44.64 | [1.95]*** | 41.90 | [2.14]*** | 10.84 | [1.09]*** | ---- | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Model Fit Statistics | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| N=338 | N=338 | N=342 | N=342 | ||||||

| F(8, 329) = 5.01 | F(8, 329) = 4.01 | F(8, 333) = 3.78 | Wald chi2 (df=8) = 33.83 | ||||||

| p = 0.0000 | p = 0.0001 | p = 0.0003 | p = 0.0000 | ||||||

| R2 = 0.11 | R2 = 0.08 | R2 = 0.08 | Pseudo R2 = 0.06 | ||||||

p < 0.1;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01

Figure 1. Plot of the effect of HIV status on depression, at various PCS12 levels.

We next performed an ordinal logistic regression, using CES-D cutoffs for low, moderate, and severe depression as an ordinal dependent variable (Column 4). Again, HIV infection is found to be significantly associated with a higher odds ratio for depression. Compared to HIV-negative controls, HIV-infected respondents were 1.6 times more likely to have severe depression (than to have moderate/low depression) and were 1.6 times more likely to have moderate to severe depression (than to have low depression).

In regressions not shown in the tables (available upon request), we did not find a relationship between HIV-infection and hazardous or harmful or dependent drinking and tobacco use.

Discussion

This study found a high rate of severe depression and poorer physical and mental health among HIV infected respondents compared to controls, similar to the findings in other developing country studies using control groups and respondents who knew their HIV status (Adewuya et al., 2007; Shisana et al., 2005; Sebit et al., 2003; Maj et al., 1994; Lindner 2006; Brandt 2007; Chikezie et al., 2013). The relationship between HIV status and poorer health outcomes remained robust after having controlled for covariates that may also contribute to differentials in health outcomes. Although HIV infection was related to depression, this effect was significant only when physical health was also poor. These findings not only emphasize the need to include management of psychological maladjustments to the disease, but also point to the potential of ART in not only improving health but also improving depression related to HIV. Our finding of an insignificant relationship between HIV status and alcohol or tobacco use is in agreement with that in other developing country studies (Shaffer, Njeri, Justice, Odero, & Tierney, 2004; Sebit et al., 2003; Adewuya et al., 2007). Psychological adjustment to the awareness of one's HIV status may, thus, impact depression but not substance use. Since the controls in our study were not matched with the cases, a preponderance of middle-aged (30-44 years) female HIV positive clients vs. younger HIV negative (18-29 years) was found. It is possible that depressive symptoms are naturally increased in older females compared to younger male patients. In this case, the difference between HIV positive and HIV negative in terms of depressive symptoms may not be attributed to HIV status but to age and gender. However, this effect was adjusted for in the regression model.

Study limitations

Our case control study design recruited individuals who came for HIV testing. If depression and health influenced testing decision in HIV infected and HIV uninfected individuals differently, our results may be biased. We did not include drug screening, standardized psychiatric measures (such as the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders), or alcohol and tobacco use over the life course. Longitudinal studies are needed to further investigate the development and course of depression and substance use disorders in relation to HIV status (Sullivan et al., 2011).

Conclusion

The study found a high rate of depression and poorer physical and mental health among HIV infected respondents compared to controls. This suggests the importance of incorporating the management of psychological health in the treatment of HIV post diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support for the study provided by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Aging (P30AG12836, B. J. Soldo, P.I.), the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, and the European Social Fund. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders. The authors thank the fieldwork coordinators Jesswill Magerman and Patricia Makuba, field supervisors Maria Vilakazi and Mantwa Mofokeng, and dedicated field workers Bridget Chiloane, Sellinah Gume, Marcia Lingwathi, Deborah Magolo, Thandiwe Mthombothi, Cleopatra Ncongwane, Nontokozo Shabangu, and Nonhlahla Sibanyoni. The authors also thank the Mpumalanga Department of Health for providing logistical support and clinic space for fieldworker training and study implementation.

References

- Adewuya AO, Afolabi MO, Ola BA, Ogundele OA, Ajibare AO, Oladipo BF. Psychiatric disorders among the HIV-positive population in Nigeria: A control study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2007;63:203–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden JM, Fergusson DM. Alcohol and depression. Addiction. 2011;106(5):906–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt R. Ph D Dissertation. University of Cape Town, Department of Psychology; 2007. Does HIV matter when you are poor and how? The impact of HIV/AIDS on the psychological adjustment of South African mothers in the era of HAART. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt R. The mental health of people living with HIV/AIDS in Africa: a systematic review. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2009;8:123–133. doi: 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.2.1.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuer E, Myer L, Struthers H, Joska JA. HIV/AIDS and mental health research in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2011;10:101–122. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2011.593373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson AJ, Sandler R, Owino FN, Matete FOG, Johnstone EC. Psychological morbidity and HIV in Kenya. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia. 1998;97:267–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb09998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikezie UE, Otakpor AN, Kuteyi OB, James BO. Depression among people living with human immunodeficiency virus infection/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Benin City, Nigeria: A comparative study. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice. 2013;16:238–242. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.110148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:725–730. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess DG, Petitto JM, Leserman J, Douglas SD, Gettes DR, Ten Have TR, Evans DL. Depression and HIV infection: impact on immune function and disease progression. CNS Spectrums. 2003;8(1):52–8. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900023452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. The 2012 National antenatal sentinel HIV and herpes simplex type-2 prevalence Survey, South Africa. Pretoria: National Department of Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Judd F, Komiti A, Chua P, Mijch A, Hoy J, Grech P, et al. Williams B. Nature of depression in patients with HIV/AIDS. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39(9):826–32. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne A, Justice A, Rollman B, McGinnis K, Rabeneck L, Weissman S, et al. Rodriguez-Barradas M. Clinical importance of HIV and depressive symptoms among veterans with HIV infection. Journal of General and Internal Medicine. 2002;17(7):512–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner GK. Psychology Dissertations. 2006. HIV and psychological functioning among black South African women: An examination of psychosocial moderating variables. Paper 19. [Google Scholar]

- Maj M, Janssen R, Starace F, Zaudig M, Satz P, Sughondhabirom B, et al. Sartorius N. WHO Neuropsychiatric AIDS Study, Cross-sectional Phase I. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:39–49. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010039006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mfusi SK, Mahabeer M. Psychosocial adjustment of pregnant women infected with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Journal of Psychology in Africa, South of the Sahara, the Caribbean and Afro-Latin America. 2000;10:122–145. [Google Scholar]

- Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Mojtabai R, Alexandre PK, Musisi S, Katabira E, Nachega JB, et al. Bass JK. Lifetime depressive disorders and adherence to anti-retroviral therapy in HIV-infected Ugandan adults: a case-control study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;145(2):221–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K. Correlates of HIV infection among people visiting public HIV counseling and testing clinics in Mpumalanga, South Africa. African Health Sciences. 2012;12(1):8–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat TJ, Richter LM, Doll HA, Buthelezi NP, Tomkins A, Stein A. Depression among pregnant rural South African women undergoing HIV testing. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1376–1378. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebit MB, Tombe M, Siziya S, Balus S, Nkomo SDA, Maramba P. Prevalence of HIV/AIDS and psychiatric disorders and their related risk factors among adults in Epworth, Zimbabwe. East African Medical Journal. 2003;80:503–512. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v80i10.8752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer DN, Njeri R, Justice AC, Odero WW, Tierney WM. Alcohol abuse among patients with and without HIV infection attending public clinics in western Kenya. East African Medical Journal. 2004;81(11):594–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, Parker L, Zuma K, Bhana A, et al. Bhana A. South African national HIV prevalence, HIV incidence, behaviour and communication survey, 2005. Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LE, Goulet JL, Justice AC, Fiellin DA. Alcohol consumption and depressive symptoms over time: a longitudinal study of patients with and without HIV infection. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;117(2-3):158–63. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szrek H, Chao LW, Ramlagan S, Peltzer K. Predicting (un)healthy behavior: A comparison of risk-taking propensity measures. Judgment and Decision Making. 2012;7(6):716–727. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuang MT, Francis T, Minor K, Thomas A, Stone WS. Genetics of smoking and depression. Human Genetics. 2012;131(6):905–15. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. How to Score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales. 2nd. Boston: Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Guidelines for controlling and monitoring the tobacco epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1998. [Google Scholar]