Abstract

School truancy is a serious concern in the U.S., with far-reaching negative consequences. Truancy has been positively associated with substance use and delinquent behavior; however, research is limited. Consequently, the Truancy Brief Intervention Project was established to treat and prevent substance use and other risky behaviors among truants. This article examines whether the Brief Intervention program is more effective in preventing future delinquency over a 12-month follow-up period, than the standard truancy program. Results indicate the Brief Intervention was marginally significant in effecting future delinquency among truants, compared to the standard truancy program. Future implications of this study are discussed.

Keywords: Truancy, delinquency, substance use, Brief Intervention

Introduction

While juvenile offending has declined in recent years (Puzzanchera, Adams, & Sickmund, 2011), school truancy, which is often a harbinger for juvenile offending, remains a serious national problem. Truancy refers to an unexcused absence from school without approval from appropriate school officials or parents; however, the exact definition of truancy varies across school districts. The inconsistent definition, as well as recording and reporting practices, of truancy makes it difficult to collect national statistics for truancy rates. Though limited in representativeness, data from the Monitoring the Future national survey for 2003 indicated that 10.5% of 8th graders and 16.4% of 10th graders had skipped school at least once within the past four weeks (Henry, 2007). Some local statistics on truancy rates are also available, and support truancy prevalence rates reported in the Monitoring the Future survey. For example, during the 2008-2009 school year 16% of all students in Las Angeles County were truant, with 57 of the 88 school districts in the county reporting truancy rates greater than 10% (Dropout Nation, 2010). Similarly, during the 2010-2011 school year, truancy rates in Colorado were above 10% for many schools, including several Denver area schools (Colorado Department of Education, 2011). Comparable statistics pointing to the high level of truancy problems can also be found in other jurisdictions (Garry, 1996).

Truancy appears to be a stepping stone toward more negative and antisocial behaviors (National Center for School Engagement, 2006). As Garry (1996) observed, truancy may be the beginning of a lifetime of problems among students who routinely skip school. Truancy has been shown to be related to a variety of educational, family and personal issues such as poor standardized test performance (Caldas, 1993; Lamdin, 1996), high school dropout (Bridgeland, Dilulio, & Morison, 2006), a stressed family life (Baker, Sigmon, & Nugent, 2001; Kearney & Silverman, 1995) and emotional/psychological functioning problems (Diebolt & Herlache, 1991; Egger, Costello, & Angold, 2003; Kearney & Silverman, 1995), substance use and abuse (Henry, Thornberry, & Huizinga, 2009; Henry & Thornberry, 2010; Soldz, Huyser & Dorsey, 2003) and both juvenile delinquency (Baker et al., 2001; Garry, 1996; Loeber & Farrington, 2000) and adult criminality (Schroeder, Chaisson, & Pogue, 2004).

From a criminological perspective, truants represent a segment of the population that is particularly at risk of becoming involved in the criminal justice system for two main reasons. First, the act of truancy alone may draw attention from the criminal justice system. In many jurisdictions, truancy qualifies as a status offense that often results in arrest and contact with the juvenile court system. Specifics for how a truancy case is handled vary across communities, with some areas utilizing informal, non-criminal justice-oriented mechanisms such as school official discretion and others utilizing formal, criminal justice-oriented mechanisms such as arrest and juvenile court petition. According to recent juvenile court statistics in 2008 for the U.S., 33% of status offense cases formally processed in juvenile courts with the filing of a petition was for truancy (Puzzanchera et al., 2011). The number of truancy cases processed in U.S. courts has increased 54% between 1995 and 2008 (Puzzanchera et al., 2011). This trend suggests that the juvenile justice system is being relied upon more often to manage truancy.

Second, truancy may lead to other delinquent or criminal behaviors that increase the likelihood of the truant becoming involved in the criminal justice system. Studies have reported a positive association between truancy and substance use and abuse (Bryant & Zimmerman, 2002; Chou, Ho, Chen, & Chen, 2006; Miller & Plant, 1999). In a series of studies examining the connection between truancy and substance use during adolescence, Henry and her associates (Henry et al., 2009; Henry & Huizinga, 2007; Henry & Thornberry, 2010) found truancy leads to the onset and escalation of substance use, specifically alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana, among adolescents. Truancy results in greater periods of unstructured and unsupervised time, which Henry and her associates speculate affords truants greater opportunities to become involved in substance use. Clearly, truant youth are at risk of using and abusing substances, which increases their likelihood of becoming involved with the criminal justice system.

Furthermore, truants are at risk of engaging in other delinquent and criminal behavior. Research has indicated truancy is associated with delinquency and crime (Baker et al., 2001; Catalano, Arthur, Hawkins, Berglund, & Olson, 1998; Garry, 1996; Onifade, Nyandoro, Davidson, & Campbell, 2010; Schroeder et al., 2004). Loeber and Farrington (2000) describe three developmental pathways to delinquent behavior for children, one of which, the authority conflict pathway, includes truancy as a characteristic. According to the authority conflict pathway to violence, truancy along with curfew violations and running away represents the last step in a pattern of defiant behavior among young boys that increases their risk of becoming involved in delinquency early on and a trajectory toward violence (Loeber & Farrington, 2000). Although the research supporting this contention is limited, in their research using longitudinal data on boys involved in the Pittsburgh Youth Study, Loeber et al. (1993) demonstrated that boys in the authority conflict pathway were at increased risk of engaging in future violence and property offending. Unfortunately, research on the connection between truancy and crime/delinquency is limited. Additional research on the association between truancy and delinquency is needed.

Based on the known associations between truancy and substance use and between truancy and future delinquency/crime, a prospective, longitudinal Brief Intervention (BI) was developed for drug-involved truant youth. The BI project received NIDA funding and is currently being implemented in a county in a southeastern state. The BI provides counseling services for drug-related issues to truant youth (described in detail below), compared to standard truancy treatment in the county. The BI assumes that deviance, particularly substance use, is a learned behavior and relies on techniques for developing effective coping and problem-solving skills to reduce and prevent future deviance (Catalano, Hawkins, Wells, & Miller, 1991; Clark & Winters, 2002). Youth are taught skills to strengthen prosocial coping and resist attitudes and behaviors that interfere with prosocial behavior. As such, the BI should reduce risk for future deviance. The purpose of the present study is to examine the effectiveness of BI in reducing contact with the justice system for the drug-involved truants. The present report describes the impact of BI services on official arrest charges for the truant youths over a 12-month, post-intervention follow-up period. Two hypotheses guided this study:

H1: Youth receiving BI services will experience a lower rate of arrest charges over the 12-month, post-intervention period, than youth receiving standard truancy services.

H2: The effect of intervention services on arrest charges will become more pronounced the longer the follow-up period.

Following a discussion of the results, implications for intervention services are considered.

Method

Sample and Procedure

The present recidivism study consists of 180 youths enrolled in the truancy intervention project between March 2, 2007 and June 22, 2010. Data on these youths’ juvenile and adult arrests, as well as time in a secure justice system or treatment facility, were available for 12 months following their date of last participation in project intervention services.

The main place of recruitment into the BI project occurred at a truancy center located at the county Juvenile Assessment Center (JAC). In addition, eligible participants were recruited from a community diversion program, and referrals from any social worker or guidance counselor associated with the school district who knew of eligible youth. Eligible youths met the following criteria: (1) age 11 to 17, (2) no official record of delinquency or up to two misdemeanor arrests, (3) some indication of alcohol or other drug use, as determined, for example, by a screening instrument (Personal Experience Screening Questionnaire [PESQ], Winters, 1992) or as reported by a social worker located at the truancy center, and (4) residence within a 25-mile radius of the truancy center. Free project services were provided in-home, and participation was voluntary.

Following the completion of the consent and assent processes, and separate baseline interviews with the youth and his/her parent/guardian, the youth and parent/guardian were randomly assigned to one of three project service conditions: (1) BI-Youth (BI-Y) that involved two BI sessions administered to the youth, (2) BI-Youth and Parent (BI-YP) that involved the same two BI sessions administered to the youth plus an additional session to the parent, or (3) STS plus a referral service overlay involving three in-home visits by a project staff member. All study procedures were approved and monitored by a local IRB.

Standard Truancy Services (STS)

In 1993, the county established a centrally-located truancy program. The truancy program relies upon a cooperative agreement among local school and law enforcement officials to identify and enforce truancy policies. Students who are not in school and do not possess a legitimate excuse from school officials or parents are taken into custody by law enforcement and transported to the truancy program located in the local JAC. Truants complete as self-report screening survey and are placed in a “classroom” (the program has been designated a school site) with a social worker from the school district, where they await the arrival of their parents.

In addition to the normal truancy services provided by the school district, STS youths/families received a referral service overlay of three weekly hour-long visits by a project staff member. Reflecting the concept of equipoise (Freedman, 1987), this referral assistance provided families in the control condition with an additional resource that is not routinely available to them, and also controlled for service exposure. On each contact occasion, staff offered families referral information for various social agencies from a resource guide containing hundreds of agency listings.

The Brief Intervention

Youth who were selected for either of the BI treatments received counseling with a BI therapist. The primary goal of the BI therapist sessions was to promote abstinence and prevent relapse through the development of adaptive beliefs and problem-solving skills. The BI incorporates elements of Rational-Emotive Therapy (RET) and Problem-Solving Therapy (PST) to develop adaptive beliefs and coping skills. Drug involvement is viewed as learned behavior that develops within a context of personal, environmental, and social factors (Catalano et al., 1991; Clark & Winters, 2002) that shape and define drug use attitudes and behaviors. Maladaptive beliefs and coping skill deficits are viewed as primary determinants of drug use. The goal of the BI therapy is to diminish factors contributing to drug use (e.g., maladaptive beliefs) and promote factors that protect against relapse (e.g., problem solving skills) (Winters, Fahnhorst, Botzet, Lee, & Lalone, in press; Winters & Leitten, 2007).

Following extensive training and utilizing fidelity assessment via authorized tape recordings, BI sessions were conducted between the BI counselor and participating family members. Each BI session was approximately 1-1/4 hours in duration, and the sessions occurred about a week apart. The first BI session with the youth focused on discussing information about the youth's substance use and related consequences, willingness to change, causes and benefits of change, and establishing goals for change. In the second session with the youth, the counselor reviewed the youth's progress with the agreed upon goals, identified risk situations associated with difficulty in achieving goals, discussed strategies to overcome barriers toward goal achievement, reviewed where the youth was in the process of change, and negotiated either continuation or advancement of goals. Informed by an integrated behavioral and family therapy approach, the parent BI session addressed the youth's substance use issues, parent attitudes and behaviors regarding this use, parent monitoring and supervision to promote progress towards their child's intervention goals, and parent communication skills to enhance youth-parent connectedness.

Research interviews

Separate from the BI counseling sessions, baseline and follow-up interviews were conducted. (No follow-up interview data were used in the analyses reported in this paper.) Each youth and parent/guardian was paid $15 for completing each baseline and follow-up interview. The baseline, in-home interviews for parents/guardians averaged 30 minutes; the youth interviews averaged one hour. The interviews were conducted by trained research staff, following local IRB approved procedures. The main data collection instruments used in the study were the Adolescent Diagnostic Interview (ADI, Winters & Henly, 1993) and the Parent/Guardian ADI (ADI-P, Winters & Stinchfield, 2003). Both the ADI and ADI-P were designed to be delivered within a highly structured and standardized format (e.g., most questions are yes/no) to capture DSM-IV criteria for substance use disorders and related areas of functioning. Item construction primarily involved advice from an expert panel and feedback from field testers. DSM guidelines and results from the statistical analysis provided the basis for scoring rules. Reliability and validity studies, involving over 1,000 drug clinic adolescents for the ADI and about 200 parents/guardians for the ADI-P, provide a wide range of psychometric evidence pertaining to inter-rater agreement, test-retest reliability, convergent validity (with clinical diagnoses), self-report measures, and treatment referral recommendations (Winters & Henly, 1993; Winters & Stinchfield, 2003).

Measures

Socio-demographic

Several demographic characteristics were measured for the youth: age; gender (0 = male, 1 = female); race (1 = African American, 0 = other); ethnicity (1 = Hispanic, 0 = other); family structure (1 = youth lives with mother alone or mother + other adult, 0 = youth lives in other arrangement). Family annual income level was categorized as: 1 =< $5,000; 2 = $5,001 to $10,000; 3 = $10,001 to $25,000; 4 = $25,001 to $40,000; 5 = $40,001 to $75,000; and 6 > $75,000. When interpreting the race and ethnicity variables, it must be noted that they can be treated as dummy variables for a three category measure. A person can be classified as African American, non-Hispanic (where race = 1 and ethnicity = 0), non-African American, non-Hispanic (where race = 0 and ethnicity = 0), or Hispanic, i.e. not African American, Caucasian, Asian, or other race, (where race = 0 and ethnicity = 1).

Family related variables

Youths were asked to indicate whether their family members ever had (1) substance abuse problems and (2) a history of mental health problems. Each of these problems was coded as follows: 0 = no problem or 1 = problem identified. An additive summary measure of eleven different stressful events experienced by youth or other family members was also created. The youths’ parents/guardians were asked to indicate if the youth or their family ever experienced various stressful/traumatic events, where 1 = ever and 0 = never. Finally, during their baseline interviews, parents were asked frequency of alcohol use in the past year. Response categories for the parent reported frequency of past year alcohol use were 1 = never, 2 = 1-5 times, 3 = 6-20 times, 4 = 21-49 times, 5 = 50-99 times, and 6 = 100 or more times.

Self-reported delinquency

Based on the work of Elliott, Ageton, Huizinga, Knowles, and Canter (1983), we measured the youths’ delinquent behavior during the past year by asking how many times they engaged in each of 23 delinquent behaviors. Youths who reported committing an act 10 or more times were also asked to indicate how often they participated in this behavior (once a month, once every two or three weeks, once a week, two to three times a week, once a day, or two to three times a day) as a means of validating reports of high frequencies. Moreover, youths were asked to indicate the age during which a committed act first occurred for each delinquent behavior. Similar to Elliott et al. (1983), we developed five summary indices of delinquent involvement: general theft (e.g., petty theft, vehicle theft/joyriding, burglary); crimes against persons (e.g., aggravated assault, fighting, and robbery); index crimes (similar to UCR Index Part I); drug sales; and total delinquency (i.e., the sum of the 23 delinquent activities).

The range of responses to the items comprising the five self-reported delinquency scales was large, ranging from no activity to hundreds (and in few cases thousands), so analysis of the frequency data as an interval scale was not appropriate as a measure of involvement in delinquency/crime. Raw numbers of offenses do form an interval scale, which might be useful if one were predicting crime rates for populations. However, the difference between no offense and 1 offense is not the same as the difference between 99 and 100 offenses in terms of involvement. A transformation was employed so that equal intervals on the transformed scale would represent differences in involvement. We interpreted the differences between 1 and 10, 10 and 100, and 100 and 1,000 offenses as being comparable. Accordingly, we log transformed the number of offenses for each scale to the base 10.

For any base, logarithms exist for all positive numbers. The choice of base does not matter if the logarithms are analyzed by a statistical procedure invariant under linear transformation, such as analysis of variance, multiple regression, discriminate analysis, or factor analysis. However, regardless of the base, the logarithm of 0 does not exist. Some other method must be employed to determine the score assigned to no offenses. For any base, 0 is the logarithm of the value 1, and 1 is the logarithm of the base. If the difference from “base” offenses (10 in this study) to 1 offense is assigned the difference in logarithm scores of 1 and 0, this provides a unit of measurement for assigning a score even lower than 0 (a negative number) to no offenses. In this study a score of –1 was assigned. This evaluates the difference between no offense and 1 offense as equal in importance as the difference between 1 offense and 10, or between 10 offenses and 100 (Dembo & Schmeidler, 2002).

The correlations between the log transformed measure of total delinquency and the other delinquency measures were sizable (mean correlation = 0.626) and statistically significant. Importantly, the skewness and kurtosis of the log transformed measure of total delinquency were dramatically lower than that of the untransformed measure. Hence, we decided to use the log transformed measure of total delinquency in our analyses. (A longitudinal study of the youths’ self-reported delinquency data of youths in this study confirmed their validity [Dembo et al., in press]).

Youth alcohol/drug use factor

A composite alcohol and drug use measure was created from a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of four indicators of substance use. First, an indicator of self-reported alcohol use was included. The ADI alcohol questions probed the youths’ use of alcohol to the point of experiencing its effects, such as feeling a buzz or getting drunk (Winters & Henly, 1993), and responses were coded as never, 1 to 4 times, or five or more times. The baseline alcohol use questions probed lifetime use up until the time of the baseline interview. (Appendix A reports the percent distributions for the four indicators used to create the alcohol/drug use factor.)

Second, a combination of urine test results and self-reports for marijuana use was used in the alcohol/drug use factor. Urine specimens were collected to assess recent drug use. The use of marijuana was probed using the Onsite CupKit® urine screen procedure, where a positive threshold level for marijuana (THC) was 50 ng/ml of urine, and the surveillance window was 5 days for moderate users, 10 days for heavy users, and 20 days for chronic users. No urine testing was done for alcohol use. The ADI questions probed the self-reported use of marijuana as: never, less than five times, or five or more times.

We combined the urine analysis (UA) and ADI marijuana data into an overall measure of marijuana use: (1) marijuana use denied, and UA test for marijuana negative; (2) marijuana use denied, and UA test data missing (due to reasons beyond the youth's control [e.g., incarcerated]); (3) UA test data missing and UA sample/specimen refused (not due to reasons beyond the youth's control); (4) UA test missing or negative for marijuana, but youths reported marijuana use one to four times; (5) UA test missing or negative, but youth reported marijuana use five or more times; (6) UA test positive for marijuana. A frequency breakdown of the six marijuana use categories indicated there were no youths in category (2), and only two youths in category (3). None of the youths with positive UA tests denied use. Hence, categories one to three were combined, and the resulting four ordinal category measure used in further analyses (see Appendix A).

Third, the youths were also asked in the ADI about their use of other drugs, including amphetamines, barbiturates, cocaine, opioids, hallucinogens, PCP, Club Drugs (e.g., Ecstasy), and inhalants. The ADI questions for other drugs probed the self-reported use as: never, less than five times, or five or more times. (Fewer than four percent of the youths were urine test positive for the other drugs tested [methamphetamines, opiates, cocaine]; hence, UA results for other drugs were excluded.)

Finally, youths reporting alcohol, marijuana, or other drug use five of more times in their lives were asked detailed questions for each drug regarding the extent, experiences, and consequences of use. The responses for each drug were keyed to DSM-IV criteria for a substance use disorder, leading to a classification of each youth as having no diagnosis, a diagnosis of being an abuser, or dependent on the drug. These diagnostic results for the three categories of drugs (alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs) were combined into an overall measure, based on their most serious diagnostic classification on any of the three mutually exclusive drug categories: 0 = no diagnosis on any of the three categories of drugs, 1 = abuse disorder on any of the drug categories and no dependence disorder on all categories, and 2 = dependence disorder on any of the three categories of drugs.

In line with previous research (Dembo et al., in press), CFA, using Bayesian estimation, confirmed the four alcohol/other drug involvement measures (baseline alcohol use, marijuana use, other drug use, and drug use diagnosis) reflected one underlying factor on which each of the measures was significantly loaded (Potential Scale Reduction [PSR] = 1.06; Posterior Predictive P-value [PPP] = 0.338). Hence, an alcohol/drug use factor score was created for further analysis.

Youth emotional/psychological functioning factor (lifetime)

A composite indicator of emotional/psychological functioning was also created for the youth. The youths reported high levels of emotional and psychological problems in response to ADI questions keyed to DSM-IV criteria in the domains of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Mania, Anxiety, and Depression (Winters & Henly, 1993). The rates of these problems in the sample and the results of efforts to create summary measures in each domain are presented in Appendix B. CFA, using Bayesian estimation, found a one factor model for each of these four domains (ADHD: PSR = 1.05, PPP = 0.500; mania: PSR = 1.05, PPP = 0.514; anxiety: PSR = 1.08, PPP = 0.315; depression: PSR = 1.07, PPP = 0.369) that was consistent with the data (see Dembo et al., in press; Dembo et al., under review). Based on these results, factor scores for each of these four domains were created for further analyses. As a final step in these analyses, a confirmatory factor analysis, using Bayesian estimation, was performed on the four emotional/psychological summary measures (depression, ADHD, anxiety, and mania). Results indicated one underlying factor, labeled emotional/psychological functioning, on which each indicator was loaded significantly. Good Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm convergence was achieved in this CFA, which indicated a low potential scale reduction value of 1.05. In addition, a very good model fit, reflected in a posterior predictive p-value of 0.476 was obtained. Hence, an emotional/psychological functioning factor score was created for further analysis.

Prior arrest charges

Since the truancy intervention project accepted youth with up to two misdemeanor charges, a measure of prior arrest charges was included in the study. Official state arrest information was also obtained on the number of arrest charges that occurred prior to the baseline interview.

Number of intervention sessions completed

We also recorded the number of BI or STS sessions project youth/family completed. This information was coded as follows: 0 = did not complete any session; 1 = completed at least one but not all sessions (including some STS telephone sessions); 2 = completed all sessions (including some STS telephone sessions).

Time-at-risk

From official records, for each recidivism follow-up period, we obtained information on the number of days each youth was in a secure facility, either treatment or incarceration facility. For each follow-up period, the number of days in a secure facility was highly skewed. Hence, we log transformed these data to the base 10 for use in our recidivism analyses. A score of -1 was assigned to zero days in a secure facility. Log transformation significantly reduced the skewness and kurtosis of each of these variables.

Intervention condition

Two forms of the BI were conducted: one with youths only (BI-Y) and one with youth and their parents (BI-YP). Both treatment conditions rely on the same social learning approach to deviance and same therapeutic techniques for developing adaptive beliefs and coping skills. Therefore, it is appropriate to combine the BI treatment groups into an overall BI effect, when comparing them to the STS group. We performed contingency table analyses and ANOVAs, comparing the BI-Y, BI-YP, and STS groups’ baseline scores on the various predictor variables. Results indicated one small, statistically significant effect for parent reported frequency of past year alcohol use (F=3.09 [2,177], p=0.048). The Eta2 value for this effect was quite small (0.034). This effect is not significant on the basis of the Bonferroni inequality threshold of 0.003 for the 16 comparisons.

Our main interest in this study was to assess the overall BI effect on the youths’ recidivism, when compared to the STS condition. Given that there were only moderate numbers of cases in each intervention condition (BI-Y, n = 60; BI-YP, n = 61; STS, n = 59) and no statistically significant differences in the outcomes when comparing the BI treatment conditions, we combined BI-Y and BI-YP youths to compare them to the STS youths (1 = BI-Y & BI-YP youth, 0 = STS youth).

Official recidivism

Considerable discussion has been devoted to reviewing the strengths and weaknesses of measuring recidivism (see, for example: Spohn & Holleran, 2002). A major issue in this discussion centers around the lack of complete information on “every crime and who committed it” (Maltz, 1984, p. 22). Although informed judgments differ on an appropriate operational definition of recidivism, Maltz (1984) and Blumstein and Cohen (1979) argue persuasively that data on arrests are a better measure of recidivism than convictions. As Blumstein and Cohen (1979, p. 565) assert, “errors of commission associated with truly false arrests are ...far less serious than errors of omission that would occur if the more stringent standard of conviction were” [used]. Hence, our operational definition of recidivism was based on the youths’ follow-up period arrest data, where three follow-up periods over a one-year follow-up period were defined following the youths’ date of last project service (i.e., BI session or STS meeting): (1) first 90 days or first 3 months, (2) second 90 days or second 3 months, and (3) the following 185 days or last 6 months.

Since youths can be arrested on multiple charges, official state arrest information was obtained on the number of arrests and the number of arrest charges during the 12-month follow-up period. In addition, adult arrest information was obtained from the county jail system, and from records from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement for youths who turned 18 years old or older during the one year follow-up period. The official arrest and charge data were coded into seven offense categories: violent felonies (e.g., robbery); property felonies (e.g., burglary); drug felonies (e.g., selling cocaine); violent misdemeanors (e.g., assault); property misdemeanors (e.g., retail theft); drug misdemeanors (e.g., marijuana possession); and public disorder misdemeanors (e.g., trespassing) (see Appendix C).

Summary scores for total arrests and total arrest charges were created for each of the three recidivism follow-up periods. This was done to assess whether the predictor variable effects differed across the follow-up periods. The number of arrest charges variables for each follow-up period reflected Poisson distributions (one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Z test values: all <.0.645, p-values = 0.800 or higher; first 3-months: M = 0.130, s2= 0.150; second 3-months: M = 0.190, s2= 0.325; last 6-months: M = 0.300, s2= 0.423). Similar results were obtained for number of arrests in each follow-up period (all one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Z test values: <. 0.089, p-values = 1.000; first 3-months: M = 0.120, s2= 0.104; second 3-months: M = 0.130, s2= 0.127; last 6-months: M = 0.230, s2= 0.225). For the analyses reported in this paper, only the variables reflecting the total number of arrest charges, not arrests, were used. For a Poisson model, “...the mean should be approximately the same as the variance.” (Berk & MacDonald, 2007, p. 5). Examination of the means and variances suggested that the Poisson model was appropriate for most of the arrest and arrest charge measures, but somewhat overdispersed for second 3-month arrest charges. However, Berk and MacDonald also discuss how this may occur with real-world data without meaning that the Poisson model has been misspecified. Although there was minor overdispersion, Poisson regression seemed most appropriate for the data presented here. (We also examined the data believed to be overdispersed using negative binomial regression and found no substantive differences than those reported here.)

Analysis Strategy

We completed separate, stepwise, Poisson regression analyses to examine the relative predictive ability of the variables discussed in the methods section on number of arrest charges. The Poisson regression analyses were run using Mplus version 6.12 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2011). The analyses involved maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. The independent variables were entered in the following historical order for the stepwise analyses: (1) family alcohol/other drug problem, (2) family mental health problem, (3) family stressful events/trauma, (4) youth age, (5) youth gender, (6) race, (7) ethnicity, (8) youth alcohol/drug use factor, (9) youth emotional/psychological functioning factor, (10) number of arrest charges prior to project entry, (11) self-reported delinquency in year prior to project entry, (12) parent reported frequency of past year alcohol use, (13) family structure, (14) family income level, (15) number of project sessions completed, (16) log of days in secure facility (justice system and/or treatment facility), (17) overall BI effect. Two cases (1%) were missing data on a predictor variable (family income level), and were excluded from the Poisson regression analyses.

Our main interest in completing the regressions in a stepwise fashion was to control for the cumulative effects of the various predictor variables before examining the effect of BI services on number of arrest charges received in each follow-up period. These stepwise analyses will also indicate whether the effects of the predictor variables differed across the three follow-up periods. For these interim analyses, the directional hypotheses were considered significant at the .05 level by a one-tailed test.

Results

Results indicated most youths/families completed all BI or STS sessions. Only three percent did not complete any BI or STS session. Ten percent completed at least one but not all sessions (including some STS telephone sessions); while 87 percent completed all sessions (including some STS telephone sessions).

Most youths in the study were male (65%), and averaged 14.79 years in age (SD = 1.30). Thirty-nine percent of the youths were Caucasian, 23% were African American, 28% were Hispanic, 2% were Asian, and 8% were from other, mainly multi-ethnic, backgrounds. Relatively few youths (14%) lived with both their biological parents. In contrast, a majority of the youths were living either with their biological mother alone (33%) or with their mother and another adult (35%). Many of the youths tended to live in modest socioeconomic circumstances. For example, only 9% of the caretakers reported an annual income of more than $75,000, while 39% reported annual incomes of $25,000 or less. Median family income was $25,000 to $40,000.

The youths reported they and their families experienced significant problems. Specifically, 56% reported a family member ever had a substance abuse problem, and 34% indicated a family history of mental health problems. Results also indicated large percentages of the youths/families experienced stressful family events, such as unemployment of a parent (51%), divorce of parents (45%), death of a loved one (61%), serious illness (33%), and a legal problem resulting in jail or detention (25%). In addition, 48% of the caretakers reported other traumatic experiences (e.g., youth being placed in foster care, not having a relationship with their father, mom's drug addiction, youth witnessing mom being verbally and physically abused by dad, separation from their mother). Overall, an average of 3.07 (SD = 1.75) family traumatic events was reported. The data also indicated a good portion of parents reported frequent alcohol use: never (38%), 1-5 times (17%), 6-20 times (22%), 21-49 times (6%), 50-99 times (5%), and 100 or more times (12%).

Results also indicated that youths were involved in delinquency. The 180 youths reported relatively high rates of delinquency during the year prior to their initial interviews. High prevalence rates were reported for index offenses (47%), crimes against persons (74%), general theft (77%), drug sales (30%), and total delinquency (93%). Further, from 2% to 14% of the youths reported engaging in the offenses (represented by the various indices) 100 times or more; some reported many hundreds of offenses. According to official records, 56 percent of project youth had at least one previous arrest (49% had one arrest). Most of these arrests were for violent misdemeanors (e.g., battery) (13%), drug misdemeanors (e.g., marijuana possession) (17%), or property misdemeanors (e.g., retail theft) (22%). Importantly, arrested youth (n = 113) received an average of 1.45 charges (SD = 0.926). Data indicated that 8% of youth spent one of more days in a secure setting in the first 3-month follow-up period, and this increased from 10% in the first 6 months to 17% in the last 6 months.

Table 1 displays the number of arrests and number of arrest charges in each of the three follow-up periods. As can be seen, the prevalence rate for arrests and arrest charges increased over the three periods. Within each follow-up period, the correlation between number of arrests and number of arrest charges was .92 or higher. For this reason, since arrest charges reflect more serious offending, we focused our recidivism outcome analyses on number of arrest charges.

Table 1.

Arrests and Arrest Charges During Each Follow-Up Period and Twelve Months Overall (n=180) in Percents

| Follow-Up Period | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First 3 months | Second 3 months | Last 6 months | Total 12 months | |||||

| Arrests | Arrest Charges | Arrests | Arrest Charges | Arrests | Arrest Charges | Arrests | Arrest Charges | |

| None | 88.3% | 88.3% | 86.7% | 86.7% | 78.9% | 78.9% | 66.1% | 66.1% |

| 1 | 11.7% | 10.0% | 12.7% | 8.9% | 18.9% | 13.3% | 26.7% | 18.9% |

| 2 | - | 1.7% | 0.6% | 3.3% | 2.2% | 7.2% | 7.2% | 10.6% |

| 3 | - | - | - | 0.6% | - | - | - | 3.3% |

| 4 | - | - | - | 0.6% | - | 0.6% | - | 1.1% |

| 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.1% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

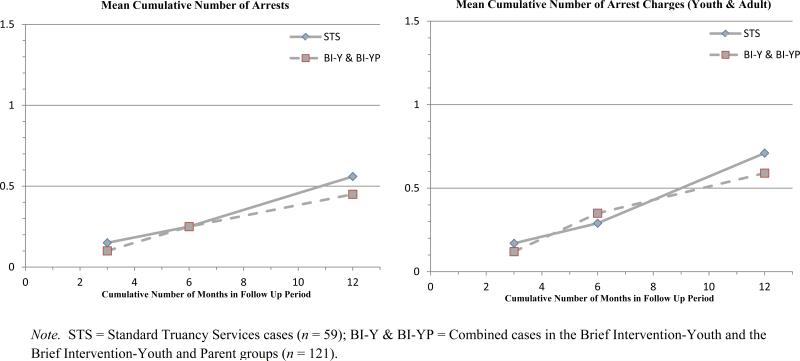

Figure 1 presents the mean, cumulative values, unadjusted for time at risk for number of arrests and number of arrest charges for the 3-month, 6-month and 12-month post-intervention periods for the STS and combined BI groups. In regard to the number of arrests, there was very small (at 3-month follow-up) or no difference (at 6-month follow-up) between the STS and combined BI groups during the first and second follow-up periods. At 12-month follow-up, however, STS group youth had a larger, but non-significant mean, cumulative number of arrests (0.56), than the BI groups (0.45). A similar trend occurred for mean, cumulative number of arrest charges at 3-month, 6-month, and 12-month follow-ups (STS youths: 0.17, 0.29, and 0.71; BI youths: 0.12, 0.35, and 0.59, for mean arrest charges across the 3-month, 6-month, and 12-month follow-ups, respectively). The graphs for both number of arrests and number of arrest charges highlight a trend over time, in which STS youth generally have more arrests and arrest charges than BI youth.

Figure 1.

Mean Cumulative Number of Recidivism Arrests and Arrest Charges During 3-Month, 6-Month, and 12-Month Post-Intervention Follow-up Period (Unadjusted for time at risk; untransformed data)

Predicting Arrest Charges During the Three Follow-up Periods

Stepwise, Poisson regression analyses were conducted to examine the relative predictive ability of the various variables discussed earlier (entered in chronological order) on the number of arrest charges during the 3-month, 6-month, and 12-month follow-up periods. The standardized coefficients, robust standard errors, and associated z-scores for the predictor variables are presented in Table 2. This interest reflected the primary purpose of the present study: to test the impact of BI on official record recidivism, as indicated by the number of arrest charges, during each of these follow-up periods.

Table 2.

Poisson Regression of Total Arrest Charges During First Three Months, Second Three Months, and Last Six Months Following Last Participation Date in Project Services (Standardized Estimates)

| First 3 Months | Second 3 Months | Last 6 Months | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Estimate | S.E. | Critical Ratio | Estimate | S.E. | Critical Ratio | Estimate | S.E. | Critical Ratio |

| Family alcohol/other drug problem | 0.389 | 0.361 | 1.077 | 0.497 | 0.287 | 1.729+ | -0.062 | 0.284 | -0.219 |

| Family mental health problem | -0.651 | 0.487 | -1.336 | 0.089 | 0.279 | 0.318 | 0.089 | 0.364 | 0.245 |

| Family stressful events/trauma | -0.225 | 0.122 | -1.848+ | -0.225 | 0.073 | -3.083** | -0.134 | 0.103 | -1.305 |

| Age | -0.023 | 0.187 | -0.122 | -0.136 | 0.110 | -1.236 | -0.270 | 0.105 | -2.569** |

| Gender (1 = female) | -1.001 | 0.511 | -1.958* | 0.025 | 0.305 | 0.082 | -0.922 | 0.389 | -2.370* |

| Race (1 = African American) | -0.797 | 0.544 | -1.465 | -0.581 | 0.322 | -1.803+ | 0.323 | 0.379 | 0.851 |

| Ethnicity (1 = Hispanic) | -1.510 | 0.609 | -2.481* | -1.175 | 0.349 | -3.363*** | 0.374 | 0.406 | 0.922 |

| Alcohol/drug use factor | 0.687 | 0.493 | 1.393 | 0.222 | 0.373 | 0.594 | 0.222 | 0.345 | 0.645 |

| Emotional/psychological functioning factor | 0.000 | 0.424 | 0.001 | -1.286 | 0.261 | -4.923*** | 0.156 | 0.289 | 0.541 |

| Number arrest charges prior to project entry | 0.087 | 0.164 | 0.532 | 0.078 | 0.111 | 0.702 | 0.071 | 0.099 | 0.724 |

| Self-reported delinquency-past year | -0.075 | 0.298 | -0.253 | 0.300 | 0.136 | 2.209* | 0.060 | 0.227 | 0.264 |

| Parent reported frequency of past year alcohol use | -0.042 | 0.119 | -0.358 | -0.094 | 0.077 | -1.229 | -0.084 | 0.117 | -0.713 |

| Family structure (1 = mother alone + others) | 0.462 | 0.526 | 0.897 | 0.078 | 0.266 | 0.292 | 0.351 | 0.412 | 0.851 |

| Family income level | -0.239 | 0.167 | -1.429 | -0.168 | 0.142 | -1.176 | -0.040 | 0.142 | -0.280 |

| Number of project sessions completed | -0.244 | 0.362 | -0.673 | 0.746 | 0.291 | 2.562** | 0.214 | 0.366 | 0.585 |

| Log of days in secure facility | 0.783 | 0.285 | 2.748* | 0.701 | 0.122 | 5.736* | 0.543 | 0.174 | 3.115* |

| Overall BI effect (1 = BI-Y & BI-YP) | -0.426 | 0.404 | -1.055 | 0.061 | 0.291 | 0.211 | -0.433 | 0.266 | -1.628++ |

| Intercept | 1.696 | 2.897 | 0.585 | 0.739 | 1.701 | 0.287 | 2.963 | 1.937 | 1.638 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.173 | 0.384 | 0.227 | ||||||

Note. The coding of the variables is discussed in the methods section. Significance levels:

Two-tailed:

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

p = 0.052 (one-tailed test).

As the results in Table 2 show, after controlling for the 15 noted predictor variables, youths receiving BI services had a near significant, lower rate of arrest charges during the third follow-up period (i.e., months 7 through 12), than STS youth (estimate = -0.433, S.E. = 0.266, p = 0.052, one-tailed test). The pseudo R2 value for this model was 0.23.

Two additional sets of analyses further refined these findings: (1) additional Poisson regression analyses indicated the overall BI effect was greatest among youth with one or more arrests prior to enrollment in the truancy project (one or more prior arrests [n = 99]: estimate = -0.596, S.E. = 0.381, Critical Ratio = -1.564, one-sided test p = 0.059; no prior arrests [n = 79]: estimate = 0.025, S.E. = 0.642, Critical Ratio = 0.038, p = n.s.); and (2) future offense reductions were greatest for property felonies (e.g., burglary, grand larceny). (Detailed reporting of these results has been omitted due to space concerns. More information is available from the senior author upon request.)

No significant, overall BI effect was found for the first 3-month and second 3-month recidivism follow-up periods. As could be expected, the log number of days in a secure facility during each follow-up period was significantly and positively related to the number of arrest charges in that time period. On the other hand, no other patterned relationships were found for any of the predictor variables on number of arrest charges across the three follow-up periods.

(We also completed a stepwise, Poisson regression analysis examining the relative predictive ability of the various predictor variables on total arrest charges over the entire 12-month follow-up period. Given the results reported in Table 1, indicating relatively few youths were arrested during the 3-month and 6-month follow-up periods, an expected, non-significant, overall BI effect was found. A detailed copy of these results is available from the senior author upon request.)

Discussion and Conclusions

Truant youth represent an understudied at-risk segment of our society who suffer various educational, familial, and antisocial problems. In particular, truancy has been linked with the initiation and habituation of substance use and future delinquency/crime. Based on such evidence, the Truancy Brief Intervention Project was established to treat truant youth involved in substance use and prevent future substance use and other at-risk behavior. The BI represents an innovative approach to identifying and providing services to drug-involved youth, with spillover effects in reducing their future delinquency—especially among those with previous contact with the justice system. As such, this study hypothesized that truants receiving the BI counseling protocol (both youth and youth and parent versions) would demonstrate less involvement in crime, measured as official arrest charges, over a one-year follow-up period, than truants receiving standard county truancy services. It was also hypothesized that the effects of the BI intervention on arrest charges (i.e., recidivism) would become more pronounced the longer the follow-up period.

While the BI group youth had a marginally significant lower number of arrest charges during the third follow-up period (months 7 through 12 of the one-year follow-up period) than STS group youth, there was no, overall support for the first hypothesis. The marginally significant BI effects at the 12-month wave suggest that this intervention has the potential of benefiting truant youths more than standard truancy programs; but further research is needed to confirm this finding. The BI project is an ongoing study. Future analyses extending the follow-up period beyond 12-months may offer stronger support for the benefit of the BI program.

Having the strongest result in the last phase of the follow-up period supports the second hypothesis. It should be noted, however, that the small percentages of youths who were arrested in the 3-month (12%) and 6-month follow-up periods (13%) made it difficult, given the sample size, to find a BI effect. In contrast, 21% of project youth were arrested one or more times in the 12-month follow-up period (see Table 1). This is likely why we found a marginal BI direct effect in the last 6-month phase of the follow-up period. Future analyses using crime data beyond the 12-month follow-up period may provide significant support for hypothesis two.

Other researchers have also found delayed or sleeper effects in their work. Prado et al. (2007) found the preventive effects of an intervention for Hispanic families (Familias Unidas) parent preadolescent training for HIV prevention (PATH) to be greatest at year 2 follow-up. Wolchik et al. (2002) found similar effects in their intervention study. It will, therefore, be important to continue examining the effects of BI beyond the 12-month follow-up period.

Importantly, Poisson regression analysis indicated the overall BI effect was greatest among youth with one or more arrests prior to enrollment in the truancy project. Among these youth, 29% receiving STS, compared to 18% receiving BI services, were arrested one or more times during the 12-month follow-up period. Future studies, involving an 18-month follow-up period, will enable us to examine these issues with more cases over a longer period of time.

The official record delinquency results we obtained are similar to those resulting from a recent study we completed on the youths’ self-reported delinquency over a 12-month follow-up period (Dembo et al., in press). In that longitudinal study, we examined the relationships between the youth's mental health, substance use and delinquency, and found a marginally significant, direct BI effect on delinquency at 3-month follow-up, and a nearly significant intervention BI effect (p = 0.052) on delinquency at 12-month follow-up. No patterned sociodemographic effects (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity) on outcome were found in this study as well.

Although the BI focuses on drug use, it is not surprising that we are also finding its salutary effect on the youths’ delinquent behavior. Since these behaviors are related (Dembo et al., in press), it could be expected that brief interventions directed to one or another of these factors would likely influence the others over time. Ellickson and her colleagues (Ellickson, McCaffrey, & Klein, 2009; Ellickson, McCaffrey, Ghosh-Dastidar, & Longshore, 2003) were among the first to identify such “spillover effects” of drug prevention activities that have implications for intervention studies. According to their work, drug prevention interventions can have “spillover effects” in reducing sexual risk behavior among youths. In general, among related risk behaviors, it could be expected that reduction in one risk behavior would result in the reduction of another—particularly if these behaviors are believed to reflect a syndrome of problem behavior (LeBlanc & Bouthillier, 2003; Jessor & Jessor, 1977). It is possible that non-specific factors, such as client expectations, readiness for change, and rapport developed between the interventionist and client, may account for at least some of the intervention effects we identified (Stout & Hayes, 2005). We were not able to assess possible important non-intervention specific factors on change in delinquent behavior. It would be important for future intervention research involving truant youth to address this issue. (We did not include truancy as an outcome in the present study for two main reasons: [1] schools differ in their recording of this event, and [2] schools report total truancy by school quarter (usually 8 weeks per quarter), not date, preventing refined analyses of these data.)

There were several limitations to this study. First, there were limitations due to the nature of the sample, which consisted of truant youth picked up by law enforcement or placed in a diversion program. Hence, the results of the study may not generalize to truant youth who do not have such agency contact/involvement. Second, the sample size used for this interim report was relatively small, precluding an examination of the fit of the models across various sociodemographic groups. Third, self-report data were mainly used as predictor variables in the analyses. While every effort was made to ensure data validity (e.g., conducting interviews in private in the youth's home, informing them of our Certificate of Confidentiality), it is possible some self-report bias is reflected in the data. At the same time, there is a consistency and coherence in our findings, as noted earlier, involving diverse data used in this study.

Planned, future analyses of our growing data set will include replicating this examination of the effects of BI services on truant youth follow-up arrests. Relatedly, where feasible, we plan to conduct multi-group analyses for gender and race/ethnicity groups.

We appreciate there are other domains of youth outcome that are important to examine, such as improvements in psychosocial functioning. These are the subject of other project studies. Our focus in this study on official delinquency reflects a major concern of school districts, law enforcement agencies, and community-based service providers. The results of this study provide a promising indication that successful BI services can reduce the youths’ likelihood of future arrests, six months to a year post intervention services, even after controlling for a large number of sociodemographic and psychosocial youth and parent factors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by Grant # DA021561, funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. We are grateful for their support. However, the research results reported and the views expressed in the paper do not necessarily imply any policy or research endorsement by our funding agency. We are also grateful for the collaboration and support of our work by the Tampa Police Department, the Hillsborough County Sheriff's Office, the Hillsborough County Public Schools, the Agency for Community Treatment Services, Inc., and 13th Judicial Circuit, Juvenile Diversion Program.

Contributor Information

Richard Dembo, Criminology Department University of South Florida 4202 E. Fowler Avenue Tampa, FL 33620 Phone: (813) 931-3345 Fax: (813) 354-0740 rdembo@usf.edu

Rhissa Briones-Robinson, Criminology Department University of South Florida 4202 E. Fowler Avenue Tampa, FL 33620

Jennifer Wareham, Department of Criminal Justice Wayne State University 3278 Faculty/Administration Building Detroit, MI 48202

James Schmeidler, Department of Psychiatry Mt. Sinai Medical School One Gustove Levy Place New York, NY 10029

Ken C. Winters, Department of Psychiatry University of Minnesota F282/2A 2450 Riverside Avenue Minneapolis, MN 55454 (Also affiliated with Treatment Research Institute, Philadelphia, PA)

Kimberly Barrett, Criminology Department University of South Florida 4202 E. Fowler Avenue Tampa, FL 33620

Rocio Ungaro, Criminology Department University of South Florida 4202 E. Fowler Avenue Tampa, FL 33620

Lora M. Karas, Mediation Program 13th Judicial Circuit 800 E. Twiggs St Tampa, FL 33602

Steven Belenko, Department of Criminal Justice Temple University 558-9 Gladfelter Hall 1115 West Berks Street Philadelphia, PA 19122 (Also affiliated with Treatment Research Institute, Philadelphia, PA)

References

- Baker ML, Sigmon JN, Nugent ME. Truancy reduction: Keeping students in school. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Washington DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Berk R, MacDonald J. Overdispersion and poisson regression. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.crim.upenn.edu/faculty/papers/berk/regression.pdf.

- Blumstein A, Cohen J. Estimation of individual crime rates from arrest records. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 1979;70:561–585. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgeland J, Dilulio JJ, Jr., Morison KB. The silent epidemic: Perspectives of high school dropouts. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Seattle, WA: 2006. A report by Civic Enterprises in association with Peter D. Hart Research Associates for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant AL, Zimmerman MA. Examining the effects of academic beliefs and behaviors on changes in substance use among urban adolescents. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2002;94:621–637. [Google Scholar]

- Caldas SJ. Reexamination of input and process factor effects on public school achievement. Journal of Educational Research. 1993;86:206–214. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, Berglund L, Olson JJ. Comprehensive community- and school-based interventions to prevent antisocial behavior. In: Loeber R, Farrington D, editors. Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. pp. 248–283. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Wells EA, Miller J. Evaluation of effectiveness of adolescent drug abuse treatment, assessment of risks for relapse, and promising approaches for relapse prevention. The International Journal of Addictions. 1991;25:1085–1140. doi: 10.3109/10826089109081039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou L-C, Ho C-Y, Chen C-Y, Chen WJ. Truancy and illicit drug use among adolescents surveyed via street outreach. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colorado Department of Education [December, 2011];School by school truancy rates. School year: 2010-2011. 2011 from http://www.cde.state.co.us/cdereval/truancystatistics.htm.

- Clark DB, Winters KC. Measuring risks and outcomes in substance use disorders prevention research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1207–1223. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.6.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Briones-Robinson R, Barrett KL, Winters KC, Schmeidler J, Ungaro R, Karas LM, Belenko S, Gulledge LM. Mental health, substance use, and delinquency among truant youths in a brief intervention project: A longitudinal study. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. doi: 10.1177/1063426611421006. in press doi: 10.1177/1063426611421006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Briones-Robinson R, Barrett KB, Winters KC, Ungaro R, Karas LM, Gulledge LM, Belenko S. Psychosocial problems among truant youth: A multi-group, exploratory structural equation modeling analysis. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2012.724290. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Gulledge L. Truancy intervention programs: Challenges and innovations to implementation. Criminal Justice Policy Review. 2009;20:437–456. doi: 10.1177/0887403408327923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Schmeidler J. Family Empowerment Intervention: An innovative service for high-risk youths and their families. Haworth Press; Binghamton, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Diebolt A, Herlache L. The school psychologist as a consultant in truancy prevention; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Association of School Psychologists; Dallas, Texas. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dropout Nation [March 14, 2012];America's truancy problem: L.A. County example. 2010 from http://dropoutnation.net/

- Egger HL, Costello EJ, Angold A. School refusal and psychiatric disorders: A community study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:797–807. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046865.56865.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, McCaffrey DF, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Longshore DL. New inroads in preventing adolescent drug use: Results from a large-scale trial of Project ALERT. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1830–1836. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, McCaffrey DF, Klein DJ. Long-term effects of drug prevention of risky sexual behavior among young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Ageton SS, Huizinga D, Knowles BA, Canter RJ. The prevalence and incidence of delinquent behavior: 1976-1980. Behavioral Research Institute; Boulder, CO: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman B. Equipoise and the ethics of clinical research. New England Journal of Medicine. 1987;317:141–145. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198707163170304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garry EM. Truancy: First step to a lifetime of problems [Bulletin] Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL. Who's skipping school: Characteristics of truants in 8th and 10th grade. Journal of School Health. 2007;77:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, Huizinga DH. Truancy's effect on the onset of drug use among urban adolescents placed at risk. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40:358.e9–358.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, Thornberry TP. Truancy and escalation of substance use during adolescence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:115–124. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, Thornberry TP, Huizinga DH. A discrete-time survival analysis of the relationship between truancy and the onset of marijuana use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:5–15. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney CA, Silverman WK. Family environment of youngsters with school refusal behavior: A synopsis with implications for assessment and treatment. American Journal of Family Therapy. 1995;23:59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lamdin DJ. Evidence of student attendance as an independent variable in education production functions. Journal of Educational Research. 1996;89:155–162. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc ML, Bouthillier C. A developmental test of the general deviance syndrome with adjudicated girls and boys using hierarchical confirmatory factor analysis. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health. 2003;13:81–105. doi: 10.1002/cbm.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP. Young children who commit crime: Epidemiology, developmental origins, risk factors, early interventions, and policy implications. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:737–762. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Wung P, Keenan K, Giroux A, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB, Maughan B. Developmental pathways in disruptive child behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:101–132. [Google Scholar]

- Maltz MD. Recidivism. Originally published by Academic Press, Inc.; Orlando, FL: 1984. Internet edition available at http://www.uic.edu/depts/lib/forr/pdf/crimjust/recidivism.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Miller P, Plant M. Truancy and perceived school performance: An alcohol and drug study of UK teenagers. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1999;34:886–893. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.6.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide, version 6. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2011. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for School Engagement . Quantifying school engagement: Research Report. Colorado Foundation for Families and Children; Denver, CO: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Onifade E, Nyandoro AS, Davidson WS, Campbell C. Truancy and patters of criminogenic risk in a young offender population. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2010;8:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Pantin H, Briones E, Schwartz SJ, Feaster D, Huang S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a parent-centered intervention in preventing substance use and HIV risk behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:914–926. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzzanchera C, Adams B, Sickmund M. Juvenile court statistics 2008. National Center for Juvenile Justice; Pittsburgh, PA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder J, Chaisson R, Pogue R. Pathways to death row for America's disabled youth: Three case studies driving reform. Journal of Youth Studies. 2004;7:451–472. [Google Scholar]

- Soldz S, Huyser DJ, Dorsey E. The cigar as a drug delivery device: Youth use of blunts. Addiction. 2003;98:1379–1386. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spohn C, Holleran D. The effect of imprisonment on recidivism rates of felony offenders. Criminology. 2002;40:329–357. [Google Scholar]

- Stout CE, Hayes RA. The evidence-based practice: Methods, models, and tools for mental health professionals. John Wiley and Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC. Development of an adolescent alcohol and other drug abuse screening scale: Personal Experience Screening Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 1992;17:479–490. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90008-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Fahnhorst T, Botzet A, Lee S, Lalone B. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. Brief intervention for drug abusing adolescents in a school setting: Outcomes and mediating factors. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Henly GA. Adolescent diagnostic interview schedule and manual. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Leitten W. Brief intervention for drug-abusing adolescents in a school setting. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:249–254. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Stinchfield RD. Adolescent Diagnostic Interview-Parent. University of Minnesota; Minneapolis: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, Millsap RE, Plummer BZ, Greene SM, Anderson ER, et al. Six–year follow-up of preventive interventions for children of divorce: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:1874–1881. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.