Abstract

Objectives

To test for any temporal association of Nodding syndrome with wartime conflict, casualties and household displacement in Kitgum District, northern Uganda.

Methods

Data were obtained from publicly available information reported by the Ugandan Ministry of Health (MOH), the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED) Project of the University of Sussex in the UK, peer-reviewed publications in professional journals and other sources.

Results

Reports of Nodding syndrome began to appear in 1997, with the first recorded cases in Kitgum District in 1998. Cases rapidly increased annually beginning in 2001, with peaks in 2003–2005 and 2008, 5–6 years after peaks in the number of wartime conflicts and deaths. Additionally, peaks of Nodding syndrome cases followed peak influxes 5–7 years earlier of households into internal displacement camps.

Conclusions

Peaks of Nodding syndrome reported by the MOH are associated with, but temporally displaced from, peaks of wartime conflicts, deaths and household internment, where infectious disease was rampant and food insecurity rife.

Keywords: Internal Displacement, Food Insecurity, TOXICOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

While clinical signs (head nodding) of Nodding syndrome are distinct and readily recognised, the diagnostic criteria used by the Ugandan Ministry of Health (MOH) between 1998 and 2011 appear to have overestimated case prevalence twofold based on the current MOH-Centers for Disease Control (CDC) case definition.

This study focused on a localised area with a very high prevalence of children with probable Nodding syndrome, as reported by the US Centers for Disease Control.7

There is uncertainty regarding the accuracy of governmental and non-governmental reports of the number of deaths, displaced persons and Nodding syndrome cases. Deaths numbers used by Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED) are known to be conservative.

Introduction

Nodding syndrome (NS) is a treatable, but otherwise progressive, childhood seizure disorder of probable environmental origin. This form of poorly understood epilepsy has occurred in certain East African populations subject to civil disruption, internal displacement, food insecurity, malnutrition and nematode infection.1 The apparent geographic association of an epidemic of NS (approximately 1998–2011) in northern Uganda and a civil war (1986–2006/2008) between government forces and the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), in which physical and psychological abuse and childhood abduction were rampant,2 has raised the possibility that wartime-related activities, as well as poverty and poor nutrition, contribute to culpability.3 4 Many war-traumatised children with NS are reported to suffer from developmental trauma disorder, a form of post-traumatic stress disorder with severe and prolonged depression, psychomotor retardation, fear and anxiety.5 Wartime activities reportedly included the use of land mines and unspecified prohibited chemical weapons delivered by Ugandan Army helicopters in 2002–2003.6 Reported ‘exposure to munitions’ emerged as a significant association with NS in Uganda7; however, this association was with ‘gun raids and not chemicals’,1 and no evidence for exposure to warfare chemicals was found during a 2002 case–control investigation of a NS epidemic in then-southern Sudan.8 A detailed analysis of possible aetiologies associated with NS considered environmental, infectious and nutritional factors.9

The Acholi Sub-Region of northern Uganda has been one of the areas most heavily impacted by conflict as well as NS. Acholi communities affected by NS attribute the illness experience to the trauma of past conflict, to poverty and to region-bound frustration over neglect.10 In 2011, the Ugandan Ministry of Health (MOH) estimated that up to 3000 children were affected in the three districts of Kitgum, Lamwo and Pader, with a prevalence of 1305 cases/100 000 in Labongo Akwang sub-county in Kitgum District.3 Diagnostic criteria used at the time for MOH case identification are unknown to the present authors. In March 2013, the MOH with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducted a cluster survey to assess the prevalence of NS in Uganda using a new consensus case definition,11 which was modified during the course of the investigation. Based on the modified definition, the estimated number of probable NS cases in children aged 5–18 years in the three northern Uganda districts was 1687 (95% CI 1463 to 1912), for a prevalence of 680 (CI 5.9 to 7.7) probable NS cases per 1000 children aged 5–18 years in the three districts.12 The 2011 MOH prevalence estimates were thus approximately double those recently reported in 2014 by MOH-CDC.

We examine annual MOH reports of NS cases in relation to regional wartime conflict, casualties and household displacement in Kitgum District (figure 1). We find a delayed temporal association between peaks in conflict events and deaths. Peaks of reported NS also correlate with peaks of household displacement and prolonged residence in camps for internally displaced people (IDP), where residents were heavily dependent on food aid.13 The camps were insecure, unsanitary and squalid, and morbidity and mortality rates were high.14 Starting in the mid-1990s, these camps were established by the government of Uganda with the goal of protecting people from the LRA, including an estimated 285 000 from Kitgum District.15

Figure 1.

Kitgum District (centre), northern Uganda, one of three districts heavily impacted by Nodding syndrome.

Methods

The total number of NS cases in Kitgum District for the years 1998–2011 was obtained from the Ugandan Ministry of Health (MOH 2011, cited in ref. 5). Conflict events and deaths in Kitgum District were derived from data obtained from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED).16 This comprehensive data set contains information from 1997 on the specific dates and locations of political violence, the types of event, the groups involved, deaths and changes in territorial control of developing states, including Uganda. Information is recorded on the battles, killings, riots and recruitment activities of rebels, governments, militias, armed groups, protesters and civilians. ACLED recorded over 80 000 individual events through early 2014, with ongoing data collection focused on Africa. Importantly, the estimated number of deaths is conservative because ACLED records the number of deaths as ‘one hundred’ when reports from which they draw data describe ‘hundreds of fatalities’. Information on the relocation of households to IDP camps was obtained from the United Nations High Commission for Refugees.17 Additional data were taken from peer-reviewed and other publicly available documents.

Results

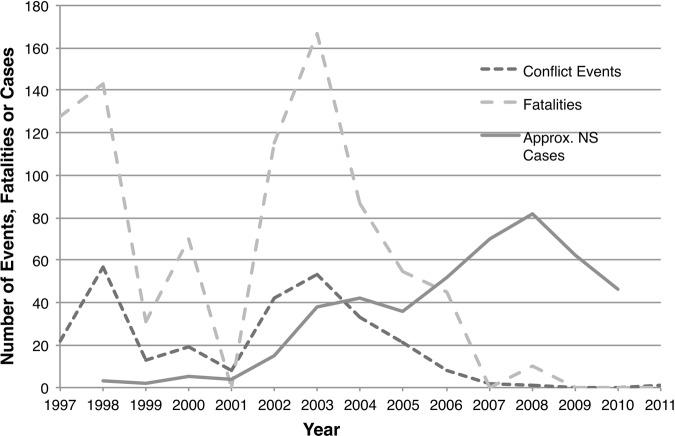

Between the years 1997 and 2011, the period for which data are available, peaks in conflict events as well as deaths arise in 1998, 2000 and 2003 (figure 2). Estimated deaths are conservative because ACLED records the maximum number of deaths per incident as ‘one hundred’. Reports of NS in northern Uganda began to appear in 1997, with the first recorded cases in Kitgum in 199815 (table 1). Cases rapidly increased annually beginning in 2001, with peaks in 2004 (2003–2005) and 2008, followed by a decline toward present-day baseline levels. The 2003–2005 and 2008 peaks of NS cases appeared 6 and 5 years, respectively, after the 1998 and 2003 conflict casualty peaks.

Figure 2.

Temporal relationship between conflict events, deaths (number of deaths) and approximate number of new Ministry of Health (MOH)-reported cases of Nodding syndrome. Kitgum District, 1997–2010/2011.

Table 1.

Annual events, ACLED-reported deaths and approximate number of new NS cases

| Year | Events16 | deaths16 | New NS cases5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | 22 | 128 | |

| 1998 | 57 | 143 | 3 |

| 1999 | 13 | 31 | 2 |

| 2000 | 19 | 70 | 5 |

| 2001 | 8 | 0 | 4 |

| 2002 | 42 | 115 | 25 |

| 2003 | 53 | 167 | 38 |

| 2004 | 33 | 87 | 42 |

| 2005 | 21 | 55 | 36 |

| 2006 | 8 | 45 | 52 |

| 2007 | 2 | 0 | 70 |

| 2008 | 1 | 10 | 82 |

| 2009 | 0 | 0 | 62 |

| 2010 | 0 | 0 | 46 |

| 2011 | 1 | 0 |

Compilation of data from ACLED and Uganda Ministry of Health, September 2011 (originally cited in refs. 16 and 5, respectively).

ACLED, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data; NS, Nodding syndrome.

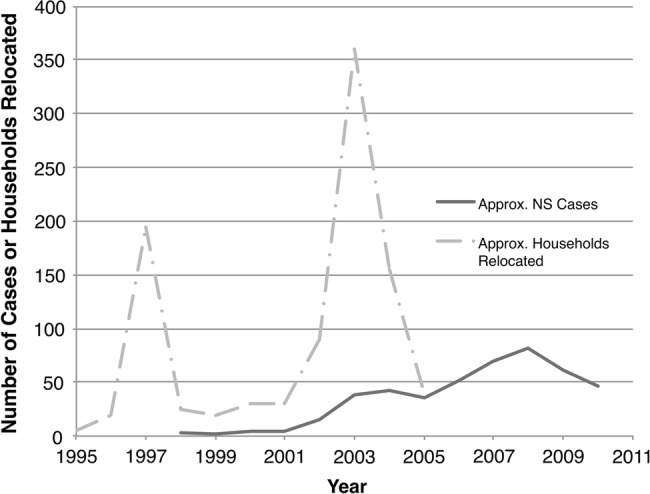

Conflict in northern Uganda resulted in the relocation of the vast majority of the Acholi population to IDP camps. Figure 3 shows that relocation to IDP camps started slowly, increased markedly after a LRA massacre in January 1997, and slowly increased over subsequent years, with the highest peak in 2003 (the year of peak deaths), before declining progressively thereafter. NS cases appeared in 1998 and peaked in 2004, and increased to reach a higher peak in 2008, 7 and 5 years, respectively, after the peak influxes of households into the IDP camps. Of some 1.1 million IDPs in Acholi region, >63% remained in camps in 2005 because of local insecurities. As of the end of June 2007, 539 550 IDPs had returned to their homes and some 916 000 IDPs remained in the camps. Another 381 000 moved to new sites closer to their homes.17

Figure 3.

Temporal relationship between new Ministry of Health (MOH)-reported cases of Nodding syndrome relative to household relocation to internally displaced people camps. Kitgum District, 2005.21

In Kitgum District, the first case of displacement took place in 1997, but the situation turned particularly bad between 2001 and 2002. Following the Uganda People's Defence Force's pursuit of the LRA into southern Sudan, there was a major escalation of LRA activity in northern Uganda. After the start of Operation Iron Fist in September 2002, a government operation aimed at crushing the LRA, almost the entire rural population (∼1.3 million) of Gulu, Kitgum and Pader was forced to move to IDP camps. Conditions were described as appalling.18 After the conflict had subsided, a sample of 210 households in Kitgum District showed that only 4.3% had not been displaced, 60% were planning to return to their homes directly, 21.4% through an intermediary location (satellite camps) and 14.3% were not planning to return to their home village.15

Conclusion

We show a possible relationship between the annual incidence of MOH-diagnosed NS and the annual number of conflict incidents and deaths in preceding years. This supports an association between NS and wartime activities.3 4 7 If the association is true, there is a latent period of approximately 5–6 years between the peak incidences of conflict/deaths and NS cases, a disease that affects children tightly clustered around the ages of 5–15 years of age.1 Civil conflict was active in Acholi Sub-Region when the first reports of NS appeared in 1998, with thousands of residents fleeing villages in Gulu District in July 1996 after a wave of LRA violence. Cases of NS declined between 2008 and 2011 in line with the cessation of the war and signing of a peace agreement between the Ugandan government and LRA in February 2008.

There are numerous reasons why conflict theoretically could be associated with NS. Exposure to warfare chemicals is readily posited but dismissed as highly improbable given the known neurotoxic properties of such substances, none of which causes repetitive head nodding from atonic seizures, let alone a progressive seizure disorder. Sudanese communities affected heavily by NS also experienced war and displacement but reported no symptoms consistent with neurotoxic exposures when questioned in 2002.9 Moreover, Tanzanian children with signs consistent with NS acquired the brain disease in the absence of war or civil conflict.19 Severe psychological trauma resulting from the sight of injury and death, and the personal fear associated therewith, have also been advanced as causal of ‘Psychological NS’, but populations in other war zones have not succumbed to a comparable illness. Furthermore, there are no known reports of NS among the thousands of children who were abducted by the LRA and forced to conduct atrocities. Documentation is available of incidents described as ‘human rights abuses by the LRA’ and ‘human rights violations by Ugandan Government forces’.2 6

There is also an apparent relationship between the peaks of NS cases in Kitgum District and earlier peak influxes of households into IDP camps. The 1997 peak influx is followed 7 years later by an elevated number of new NS cases in 2004 (2003–2005), and the 2003 large influx of households anticipates a larger peak in new NS cases 5 years later in 2008. Conditions in the IDP camps were exceptionally poor, with overcrowding, violence, food insecurity and high potential for disease transmission. In 2005, a government survey of Kitgum estimated an IDP population of 310 111 persons, 21% of whom were under 5 years of age. At the time of the survey, over 66% of children were reported to have been ill sometime in the previous 2 weeks. Crude mortality rates were ∼2 deaths per 10 000 per day and double that rate for children under the age of 5 years. Top self-reported causes of death in IDP camps were malaria/fever (34.7%), AIDS (15.1%) and violence (10.5%). An estimated 1216 persons were killed and an additional 304 (mostly children) abducted during the first half of 2005. Water was obtained from protected sources but water intake was low and waiting times high. Infant feeding practices were poor and, for children under the age of 5 years, the traditional disease concept of two lango or gimiru, a combination of oral thrush, malnutrition and diarrhoea, was the second most commonly reported cause of death.20 The World Food Programme provided food because ability to grow crops was limited due to security concerns.15 Food quality was often extremely poor and, under normal conditions, would have been considered inedible. In some cases, security was so weak that food deliveries did not occur, with resulting hunger and malnutrition. Insecurity in IDP camps led to a migration of children (‘night commuters’) to seek shelter in Kitgum hospitals, schools, municipal buildings, verandahs, parking lots and other open spaces.21 Unfortunately, there are no data on the incidence of NS among night commuters.

The major limitation of this study is the accuracy of reports of the number of deaths, displaced persons and NS cases. Cited data are drawn from reports prepared by the Uganda MOH, international bodies and non-profit and other organisations. Reason for caution is illustrated by the report of a massacre on 7–12 January 1997 when “up to 412 civilians were killed by armed attackers in northwest Kitgum subcounties of Lokung and Palabek and in nearby areas”.6 This contrasts with the report of 128 deaths in Kitgum throughout 1997 recorded in the ACLED database.16 ACLED death data are derived conservatively from a variety of sources, including research publications and reports from humanitarian agencies and local media. If a report mentions hundreds of deaths, ACLED records the number as ‘one hundred’, which might explain the discrepancy.

Taken in concert, there appears to be a reasonable correlation between IDP camp intake peaks and delayed NS peaks, which in turn show correspondence with prior conflict incidents and deaths. Since the disease is clearly associated with prevailing environmental factors, but apparently not with polluted drinking water, suspicion falls on infectious and/or nutritional factors, including food type, quality, spoilage or chemical contamination. This meshes with 2002 findings from then-southern Sudan where NS was associated with onchocerciasis and prevalent in sessile communities dependent for food on crops grown in small gardens but absent in cattle herders, the latter having access to meat, blood and milk.9 When affected South Sudanese were questioned by CDC investigators as to the source of their food, an unexplained association emerged between NS and use of garden food rather than food purchased from the market or provided by the World Food Programme (US Centers for Disease Control, unpublished data). Additionally, a link between food available in IDP camps and NS would explain the apparent absence of this brain disorder in abducted children: while they served as fighters, porters, sex slaves and baby-sitters, they likely had better access to food, including freshly killed human body parts. Thus, the nature of any association between NS, nutrition and materials used for food, in addition to infection with nematode microfilariae (particularly Onchocerca volvulus) and war-related neuropsychological factors, would appear worthy of focused investigation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to study design, data acquisition (principally JLL) and data interpretation (principally PSS.) The paper was written by PSS and edited by co-authors JLL and VSP.

Funding: This work was supported by the US National Institute of Neurological Disorders & Stroke, grant number 1 R01 NS079276.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Dowell SF, Sejvar JJ, Riek L et al. . Nodding syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis 2013;19:1374–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anon. Abducted and Abused: Renewed Conflict in Northern Uganda. Human Rights Watch 15, 12A, 2003. http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/uganda0703.pdf (accessed Jul 2014).

- 3.Bukuluki P, Ddumba-Nyanzi I, Kisuule JD et al. . Nodding syndrome in post-conflict northern Uganda: a human security perspective. Global Health Govern 6, 2012. http://www.ghgj.org (accessed 10 Jul 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitara DL, Amone C. Perception of the population in Northern Uganda to nodding syndrome. J Med Med Sci 2012;3:464–70. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Musisi S, Akena D, Nakimulu-Mpungu E et al. . Neuropsychiatric perspectives on nodding syndrome in northern Uganda: a case series study and a review. Afr Health Sci 2013;13:205–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulindwa HE. Detailed Atrocities Caused in the Acholi Sub Region. 26 February2012. https://www.mail-archive.com/ugandanet@kym.net/msg27528.html (accessed 10 Jul 2014)

- 7.Foltz JL, Makumbi I, Sejvar JJ et al. . An epidemiologic investigation of potential risk factors for Nodding syndrome in Kitgum District, Uganda. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e66419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tumwine JK, Vandemaele K, Chungong S et al. . Clinical and epidemiologic characteristics of nodding syndrome in Mundri County, southern Sudan. Afr Health Sci 2012;12:242–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spencer PS, Vandemaele K, Richer M et al. . Nodding syndrome in Mundri County, South Sudan: environmental, nutritional and infectious factors. Afr Health Sci 2013;13:183–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Bemmel K, Derluyn I, Stroeken K. Nodding syndrome or disease? On the conceptualization of an illness-in-the-making. Ethn Health 2014;19:100–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. International Scientific Meeting on Nodding Syndrome. Meeting report. Kampala, Uganda, 30 July–1 August 2012, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2012. http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/Nodding_syndrom_Kampala_Report_2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyengar PJ, Wamala J, Ratto J et al. . Prevalence of nodding syndrome—Uganda, 2012–2013. MMWR Morb Wkly Rep 2014;63:603–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Food Programme. Emergency Food Security Assessment of IDP Camps in Gulu, Kitgum, Kira and Pader Districts, March-May 2005. September2005. http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/ena/wfp079422.pdf (accessed 10 Jul 2014).

- 14.Bozzoli C, Brzzo T. Child mortality and camp decongestion in post-war Uganda. Microcon Research Working Paper 24, Brighton, May2010. http://www.microconflict.eu/publications/RWP24_CB_TB.pdf (accessed 10 Jul 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Food Programme. Food Security Assessment of IDP Camps in Gulu, Kitgum, and Pader Districts, October 2006. Final Report. January2007. http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/ena/wfp120444.pdf (accessed 10 Jul 2014).

- 16.Raleigh C, Linke A, Håvard H et al. . Introduced ACLED—armed conflict location and event data. J Peace Res 2010;47:1–10 http://www.acleddata.com (accessed 10 Jul 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russo R. Uganda's IDP Camps Start to Close as Peace Takes Hold. 11 September2007. http://www.unhcr.org/46e6a68013.html (accessed 10 Jul 2014).

- 18.Boas M, Hartley A. Northern Uganda internally displaced persons profiling study. Vol 1 United Nations Development Programme, 2005. http://www.fafo.no/ais/africa/uganda/IDP_uganda_2005.pdf (accessed 10 Jul 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spencer PS, Palmer VS, Jilek-Aall L. Nodding syndrome: origins and natural history of a longstanding epileptic disorder in sub-Saharan Africa. Afr Health Sci 2013;13:176–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uganda Ministry of Health. Health and mortality survey among internally displaced persons in Gulu, Kitgum and Pader Districts, Northern Uganda. World Health Organization, Geneva, 2005. http://www.who.int/hac/crises/uga/sitreps/Ugandamortsurvey.pdf (accessed 10 Jul 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21.United Nations. An Account of Life in Northern Uganda. oOCHA RSO-CEA and IRIN. 2004. http://www.irinnews.org/pdf/in-depth/when-the-sun-sets-revised-edition.pdf (accessed 10 Jul 2014).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.