Abstract

This study examines the relationship between sexual experience and various drinking measures in 550 incoming first-year college females. During this transition period, sexually experienced participants reported stronger alcohol expectancies and endorsed higher drinking motives, and drank more frequently and in greater quantities than sexually inexperienced participants. Sexual status was also a significant predictor of alcohol-related nonsexual consequences, over and above amount consumed. Furthermore, controlling for drinking, sexual status moderated the relationship between coping motives and consequences. Among women who endorsed strong coping motives for drinking, sexual experience was linked to greater nonsexual alcohol-related consequences. Implications for prevention and intervention are discussed.

Keywords: alcohol, alcohol-related consequences, college females, college transitions, drinking motives, sexual experience

Introduction

In recent years, frequent and excessive alcohol consumption among college females has gained recognition as a serious public health problem. Evidence of escalating drinking rates among female college students, particularly in contrast to stabilized rates among comparable males, has drawn attention to college women's drinking behaviors and associated ramifications (Berkowitz & Perkins, 1987; Holdcraft & Iacono, 2002; Pullen, 1994; Wechsler et al., 2002; Wechsler, Lee, Nelson, & Kuo, 2002). In addition to alcohol-induced negative consequences such as compromised judgment, academic and social impairment, violence, car accidents, and fatalities (Engs, Diebold, & Hanson, 1996; Wechsler et al., 2000; Wechsler, Moeykens, Davenport, Castillo, & Hansen, 1995), college women face significant gender-specific alcohol-related risks ranging from unsafe sex and sexual victimization to “telescoped” progression of adverse health outcomes, including alcohol addiction as well as liver and cardiovascular disease (CASA, 2003; Randall et al., 1999; Wechsler, Davenport, Dowdall, & Moeykens, 1994; Wechsler et al., 1995; Wechsler et al., 2000). Inherent physiological differences, because of which women metabolize alcohol more slowly and reach higher blood alcohol concentrations (BAC) more quickly than males, exacerbate such risks (Jones & Jones, 1976; NIAAA, 2002; Perkins, 2000).

Not only do college women appear to drink considerably more than same-aged non-college-attending counterparts (Crowley, 1991; Johnston, O'Malley, & Bachman, 2002; Slutske et al., 2004), but they tend to drink more frequently and heavily during the college years than at any other period in their lives (Gomberg, 1994; Knibbe, Drop, & Muytjens, 1987). Specifically, the transition to college holds significant risk for alcohol misuse and associated negative consequences (O'Neill, Parra, & Sher, 2001; Sher & Rutledge, 2007). For example, a Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) longitudinal study that followed a national sample of 1,220 females from elementary school through college affirmed that the single largest increases in reported drinking occurred from high school to college (CASA, 2003). In examining why matriculating into college appears to engender such dangerous outcomes, researchers have pointed to collegiate cultures that tend to endorse heavy social drinking (Presley, Meilman, & Leichliter, 2002) as instilling a “drinking style of excess and intoxication” (Wechsler & Nelson, 2008, p. 3). Others have found that moving away from home, which coincides with unprecedented freedom from parental monitoring and increased import of peers, is central to excessive drinking rates among incoming college students (Bachman, Wadsworth, O'Malley, Johnston, & Schulenberg, 1997; White et al., 2006), particularly females (Johnston et al., 2002). Clearly, college entrance poses unique hazards for young women. In fact, the first six weeks on campus, which are crucial to overall adjustment as well as the development of enduring drinking behaviors, have become a focal point of many alcohol-related campus initiatives and prevention efforts (NIAAA, 2002).

In order to facilitate effective intervention strategies, researchers have explored students' motivations for consuming alcohol (Cooper, 1994). Considered to be the most proximal impetuses of consumption, examination of drinking motives have become a fruitful approach to study antecedents leading to problematic alcohol usage (Cox & Klinger, 1988; Kuntsche, Knibbe, Engels, & Gmel, 2007; Westmaas, Moeller, & Woicik, 2007). Not surprisingly, social drinking motives are found to be most commonly endorsed by college students (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005). The pervasiveness of alcohol-based social settings on college campuses provides venues to help in navigating new social environments and establishing friendship networks for incoming first-year college students. Moreover, college students are prone to overestimate peers' alcohol usage and believe that intoxication facilitates social interaction—both of which contribute to increased socially motivated drinking (LaBrie, Hummer, & Neighbors, 2008; Pedersen & LaBrie, 2008). Evidence suggests that the salience of peer approval and intimate relationships to female identity may complicate the motivations and consequences of alcohol misuse among incoming college women (Gleason, 1994; Vince-Whitman & Cretella, 1999). For example, LaBrie, Huchting, and colleagues (2008) revealed a main effect of social drinking on related problems among two distinct samples of college women, and highlighted the paradoxical complexity of relational health, which was found to increase alcohol intake, but protect against negative alcohol-related consequences.

Coping-motivated drinking, on the other hand, is found to be most predictive of heavy consumption (Cooper, Agocha, & Sheldon, 2000; Karwacki & Bradley, 1996; Labouvie & Bates, 2002; LaBrie, Hummer, & Pedersen, 2007), and is consistently tied to negative consequences, over and above the amount of alcohol consumed (Kassel, Jackson, & Unrod, 2000; Simons, Correia, & Carey, 2000; Windle & Windle, 1996). Consuming alcohol as a means to cope with stressful life events is thought to be especially perilous as it originates from unresolved negative internal states, and is associated with deficient internal coping mechanisms, poor psychosocial health, lack of volitional control over drinking, and alcohol dependency (Carpenter & Hasin, 1999; Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995). Notably, evidence supports that women may be more susceptible to drink as a result of stressful events or negative affect than males (Annis, Sklar, & Moser, 1998; Bischof, Rumpf, Meyer, Hapker, & John, 2005; Park, Armeli, & Tennen, 2004; Timko, 2005). College transitions, for instance, are found to be more emotionally challenging for women than men. Compared to male peers, incoming college females appear to exhibit greater interpersonal distress in managing the amalgamation of newfound responsibilities (i.e., autonomy from parents, rigorous academic pressures, unfamiliar peer groups), which may heighten risks for coping-motivated drinking (Hoffman, 1984; Lapsley, Rice, & Shadid, 1989). Although extensive research has extrapolated direct linkages between both social and coping-motivated drinking to college women's drinking behaviors and consequences, research has yet to ascertain what variables may moderate these fundamental associations.

Given that alcohol misuse and sexual activity often occur concomitantly on college campuses, and roughly half of females entering college report being sexually experienced (Alan Guttmacher Institute, 1994; Division of Adolescent & School Health, CDC, 1997), identifying the extent to which sexual status and risky drinking behaviors may be associated for women immersed in such settings is a worthy endeavor. Compared to sexually inexperienced counterparts, sexually experienced college women are found to engage in more frequent and excessive alcohol consumption, and experience greater unsafe alcohol-related sexual behaviors and consequences, such as unprotected sex, casual sex, and/or sexual victimization (Brown & Vanable, 2007; Leigh & Schafer, 1993; Parks, Romosz, Bradizza, & Ya-Ping, 2008). Although the relationship between college women's sexual experience and drinking-induced sexual hazards has been demonstrated, research has largely neglected to investigate how sexual experience, motivations of consumption, and amount of alcohol consumed might uniquely contribute to predicting nonsexual alcohol-related consequences. Nevertheless, sexual-based alcohol expectancies (i.e., sexual disinhibition, sexual opportunities, sexual pleasure, interpersonal closeness) may predispose sexually active students to heavier drinking and more frequent intoxication (Carey, 1995; Thombs, Wolcott, & Farkash, 1997; Wilsnack, 1991). Further evidence suggests that, compared to sexually abstaining peers, sexually active youths are more likely to possess sensation-seeking, deviant, or non-conformist personalities (Arnett, 1996; Baer, 2002), which also may heighten the likelihood for underage drinking and dangerous outcomes. Female students with stronger and more positive sex-related alcohol expectancies or sensation-seeking dispositions may be susceptible to riskier drinking during transitional periods typified by excessive and socially endorsed alcohol consumption.

The current study examines drinking motives, consumption, and consequences among a cohort of sexually experienced and sexually inexperienced first-year college females at the beginning of their college experience. Sexually experienced female youths may face heightened vulnerabilities to the confluence of unprecedented changes that incoming students encounter upon transitions to college, including the desire to establish new friendships, copious opportunities for underage drinking and sex, newfound independence, and limited parental oversight. We predict that sexually experienced first-year college females will report higher drinking motives, endorse more positive alcohol expectancies, and drink at greater rates compared to sexually inexperienced peers.

Furthermore, the amount of alcohol consumption, social motives, and coping motives should each uniquely predict negative consequences in this cohort, even after controlling for amount consumed. Also as part of this analysis, we seek to extend previous research focused on sexually experienced college women's greater drinking-induced sexual risks by hypothesizing that, compared to sexually inexperienced peers, sexually experienced women should experience more adverse nonsexual drinking-related consequences. Finally, this analysis will also explore whether sexual status statistically moderates the effect of drinking motives on negative alcohol-related nonsexual consequences. It is expected that among women who endorse greater coping and social drinking motives, those who are sexually experienced should encounter more alcohol-related nonsexual repercussions than those who are sexually inexperienced. Explicating how sexually experienced and sexually inexperienced women may differ with regard to drinking motives, consumption, and nonsexual consequences during the challenging transition to college aims to inform and enhance targeted prevention and intervention policy.

Method

Participants

A total of 550 first-year female undergraduate students at a midsized private university participated in this study. Sample size for analyses ranged from 523 to 550 due to participants skipping individual items. However, at least 95% of the total sample responded to each item used in the analyses and no statistical differences existed between completers and non-completers on any demographic or alcohol or sex variables. Participants had a mean age of 17.92 (SD = .34). Racial composition was 56.3% Caucasian, 14.6% Hispanic/Latino, 8.7% Asian/Pacific Islander, 5.6% black/African American, with 10.9% reporting more than one race, and 3.9% indicating “Other/Decline to State.”

Design and Procedure

This sample was taken from two cohorts of a larger intervention research project (N = 550) that were held during two sequential school years 2005–2006 (cohort 1) and 2006–2007 (cohort 2). During the first month on campus, each participant received a letter informing them of an opportunity to participate in an upcoming study on women, alcohol, and health. After receiving the letter, and four weeks after her arrival on campus, each female participant received an e-mail inviting her to participate in the study. The e-mail contained a link to the online consent form and survey. If a participant clicked on the link, she was directed to and electronically “signed” a local IRB-approved informed consent form before completing the online survey. Participants received nominal stipends for their participation in the study. The two intervention studies included this pre-intervention online questionnaire as well as group motivational enhancement intervention sessions and 10 subsequent weekly online diaries (LaBrie, Hummer et al., 2008). Data used in the current study were collected entirely during the pre-intervention online survey, which took place at the end of the first month during the first term of college.

Measures

Demographic Characteristics

The online phic information including age, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), and high school grade point average (GPA).

Alcohol Expectancies

The 40-item Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire (AEQ-3; George, Frone, Cooper, & Russell, 1995) assesses beliefs regarding the positive and negative effects an individual expects to obtain from alcohol consumption. The AEQ is comprised of a comprehensive list of expected circumstances or situations that might be experienced while consuming alcohol. Each participant was asked to rate how much she agreed with each statement (e.g., “I'm more romantic when I drink,” “A few drinks makes it easier to talk to people,” “I'm more likely to get into an argument if I've had some alcohol,” “Alcohol lowers muscle tension in my body”) using a 1 (not applicable) to 6 (strongly agree) scale. The eight AEQ subscales, comprised of five questions each, revealed adequate reliability in the current sample; Social Expressiveness (α = .95), Power and Aggression (α = .90), Social and Physical Pleasure (α = .93), Careless Unconcern (α = .91), Cognitive and Physical Impairment (α = .94), Tension Reduction and Relaxation (α = .90), Sexual Enhancement (α = .90), and Global Positive Change (α = .90).

Drinking Motives

Motivations for drinking alcohol were assessed using the 20-item Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ-R; Cooper, 1994), encompassing the 4 sub-scales of Coping (α = .87), Conformity (α = .79), Enhancement (α = .92), and Social Motives (α = .94). The DMQ-R has proven to be the most rigorously tested and validated measurement of drinking motives (Maclean & Lecci, 2000; Stewart, Loughlin, & Rhyno, 2001). Respondents were prompted with, “Thinking of the time you drank in the past 30 days, how often would you say that you drank for the following reasons?” Participants rated each reason (e.g., “because it makes social gatherings more fun” and “to fit in”) on a 1 (almost never/never) to 5 (almost always/always) scale.

Alcohol Use

Alcohol use and behavior within the past 30 days was measured using single-item self-report questions. Participants reported the number of drinking days per month (“On average, how many days per month did you drink alcohol?”), average drinks per occasion (“On average, how many drinks did you have each time you drank?”), maximum drinks per occasion (“What is the maximum number of drinks you drank at any one time?”), and binge episodes during the past two weeks (“Think back over the past two weeks. How many times have you had four or more drinks in a two-hour period?”). All questions were on an open-ended response format. The total drinks per month variable was calculated by multiplying drinking days per month by average drinks per occasion.

Alcohol-Related Negative Nonsexual Consequences

The 23-item Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989) (α = .87) assessed alcohol-related consequences. Using a 0 (never) to 4 (more than 10 times) scale, participants indicated how many times in the past month they had experienced each stated circumstance (e.g., “Caused shame or embarrassment to someone” or “Felt that you had a problem with school”). None of the items on the RAPI include circumstances related to sexual consequences.

Sexual Status and Behavior

Each respondent was asked, “Have you had sexual intercourse before?” If she responded that she had previously engaged in sexual intercourse, she was asked six self-report single-item questions including, “At what age did you first have sex?”, “How many sexual partners have you had in the past three months?”, “How many sexual partners have you had in your life?”, “What percentage of the time do you use a condom?”, “What percentage of your sexual events involved prior drinking?”, and “What percentage of the time did you use a condom when drinking occurred before sex?”

Results

Analytic Plan

Female college students reporting they have engaged in sexual intercourse were classified as sexually experienced (43.8%); the remaining 56.2% were classified as sexually inexperienced. The demographic characteristics of the sexually experienced and inexperienced participants were compared. To examine in further detail the sexually experienced subsample, descriptive data provided information on their sexual behaviors. Then, independent samples t-tests assessed significant differences between the sexually experienced and sexually inexperienced groups on various alcohol-related psychosocial and behavioral-dependent measures.

Finally, a four-step hierarchical multiple regression model was estimated to offer a more comprehensive view of predictors uniquely contributing to variance in alcohol-related nonsexual negative consequences. In Step 1, demographic covariates (age, race/ethnicity, SES, and GPA) were entered. Alcoholic drinks (total drinks per month) was controlled for in Step 2. Sexual status and each of the four DMQ subscales (Coping Motives, Conformity Motives, Enhancement Motives, and Social Motives) followed at Step 3. In Step 4, to determine the moderating role of sexual status, we computed interaction terms involving sexual status and each of the DMQ sub-scales. Alcohol-related nonsexual negative consequences (RAPI) served as the dependent measure. All predictors were standardized prior to computation of interaction terms. As such, problems associated with multicolli-nearity were not encountered. The multiple regression analysis was estimated, graphed, and interpreted according to procedures put forth by Aiken and West (1991).

Descriptive Data

No demographic differences were discovered on age, race/ethnicity, and SES between the sexually experienced and sexually inexperienced groups. However, these two groups differed on GPA, as sexually inexperienced females tended to receive better high school report card grades.

Among the sexually experienced females, mean age of first sexual encounter was 16.50 years (SD = 1.12), mean number of sexual partners in the past 3 months was 1.16 (SD = .80), and mean number of lifetime sexual partners was 2.31 (SD = 2.40). This group of sexually experienced females also self-reported on average that 72.47% (SD = 38.65) of their sexual encounters involved condoms, 13.06% (SD = 24.17) of their sexual encounters involved prior drinking, and condom usage occurred in 68.29% (SD = 43.37) of their sexual encounters when prior drinking was involved.

Mean Differences in Alcohol-Related Psychosocial and Behavioral Measures

Systematic differences emerged on all the alcohol-related psychosocial and behavioral dependent measures (Table 1). Particularly, sexually experienced compared to sexually inexperienced females had significantly higher means on each of the AEQ and DMQ subscales. Not surprisingly, the largest effect size was exhibited on the alcohol expectancy of Sexual Enhancement. Furthermore, sexually experienced participants consumed significantly higher levels of alcohol—drinking days per month, average drinks per occasion, maximum drinks per occasion, binge episodes past two weeks, and total drinks per month—than the sexually inexperienced participants. The sexually experienced females also were significantly more likely to encounter alcohol-related negative nonsexual consequences (RAPI).

TABLE 1. Psychosocial and Behavioral Differences Between Sexually Experienced and Sexually Inexperienced Females.

| Variable | Sexually experienced | Sexually inexperienced | t-test | Cohen's d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |||

| Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire (AEQ) | ||||||

| Social Expressiveness | 3.84 | (1.62) | 2.60 | (2.07) | 7.51*** | 0.66 |

| Power and Aggression | 3.02 | (1.40) | 1.88 | (1.55) | 8.78*** | 0.77 |

| Social and Physical Pleasure | 3.89 | (1.53) | 2.64 | (1.94) | 8.11*** | 0.71 |

| Careless Unconcern | 3.58 | (1.49) | 2.45 | (1.96) | 7.26*** | 0.64 |

| Cognitive and Physical Impairment | 3.88 | (1.44) | 2.68 | (2.04) | 7.61*** | 0.67 |

| Tension Reduction and Relaxation | 3.28 | (1.52) | 2.10 | (1.77) | 8.15*** | 0.71 |

| Sexual Enhancement | 2.98 | (1.55) | 1.49 | (1.46) | 11.37*** | 1.00 |

| Global Positive Change | 2.49 | (1.31) | 1.60 | (1.42) | 7.38*** | 0.65 |

| Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ) | ||||||

| Coping Motives | 1.56 | (0.70) | 1.28 | (0.58) | 5.00*** | 0.44 |

| Conformity Motives | 1.25 | (0.47) | 1.16 | (0.38) | 2.40* | 0.21 |

| Enhancement Motives | 2.34 | (1.19) | 1.68 | (1.00) | 6.93*** | 0.61 |

| Social Motives | 2.49 | (1.21) | 1.78 | (1.03) | 7.30*** | 0.64 |

| Drinking Behavior | ||||||

| Drinking days per month | 4.85 | (4.87) | 2.27 | (3.54) | 7.09*** | 0.62 |

| Average drinks per occasion | 3.05 | (2.12) | 1.77 | (2.04) | 7.08*** | 0.62 |

| Maximum drinks per occasion | 5.56 | (3.89) | 3.28 | (3.87) | 6.71*** | 0.59 |

| Binge episodes past two weeks | 1.26 | (1.96) | 0.59 | (1.49) | 4.44*** | 0.39 |

| Total drinks per month | 20.72 | (25.40) | 8.96 | (17.59) | 6.30*** | 0.55 |

| Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI) | 4.08 | (5.43) | 1.40 | (2.84) | 7.33*** | 0.64 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Regression Predicting Alcohol-Related Negative Nonsexual Consequences

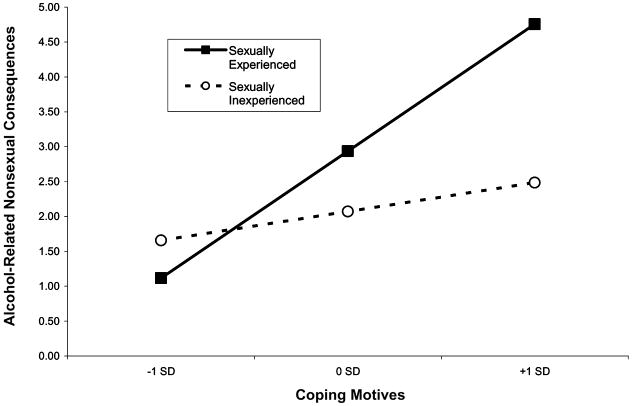

In the hierarchical multiple regression model predicting alcohol-related negative nonsexual consequences, each block of predictors uniquely explained a significant proportion of variance at their step of entry (Table 2). The final model, involving entry of all predictors, accounted for a substantial 53% of the variance in alcohol-related negative consequences, F(14, 508) = 41.38, p < .001. The following emerged as statistically significant predictors in the final model: total drinks per month (β = .31, p < .001), sexual status (β = .10, p < .01), Coping Motives (β = .23, p < .001), Conformity Motives (β = .10, p < .05), Enhancement Motives (β = .17, p < .05), and sexual status × Coping Motives (β = .16, p < .001). The statistically significant moderating effect, controlling for all other variables in the regression, is depicted in Figure 1. As Coping Motives increased from low to high, sexually experienced females encountered greater alcohol-related negative nonsexual consequences than their sexually inexperienced counterparts. Simple slope analyses, evaluating whether each of these two slopes statistically deviated from a flat slope of zero, indicated a positive relationship between Coping Motives and alcohol-related negative nonsexual consequences for both the sexually experienced (β = 2.80, p <.001) and the sexually inexperienced (β = .63, p < .001) females.

TABLE 2. Hierarchical Multiple Regression Predicting Alcohol-Related Nonsexual Consequences.

| Predictor | R2 change | Final model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| B | SE | B | ||

| Step 1: Demographic Characteristics | .05*** | |||

| Age | 0.05 | 0.13 | .01 | |

| Race/ethnicitya | 0.04 | 0.14 | .01 | |

| SES | −0.07 | 0.14 | −.02 | |

| GPA | −0.20 | 0.14 | −.05 | |

| Step 2: Alcoholic Drinks | 30*** | |||

| Total drinks per month | 1.35 | 0.18 | .31*** | |

| Step 3: Sexual Status and DMQ | 15*** | |||

| Sexual statusb | 0.43 | 0.14 | .10** | |

| Coping Motives | 1.03 | 0.19 | 23*** | |

| Conformity Motives | 0.42 | 0.17 | .10* | |

| Enhancement Motives | 0.72 | 0.30 | .17* | |

| Social Motives | 0.01 | 0.30 | .00 | |

| Step 4: Interactions | .03*** | |||

| Sexual status × Coping Motives | 0.70 | 0.19 | .16*** | |

| Sexual status × Conformity Motives | 0.09 | 0.17 | .02 | |

| Sexual status × Enhancement Motives | −0.25 | 0.28 | −.06 | |

| Sexual status × Social Motives | 0.21 | 0.29 | .05 | |

For race/ethnicity, 1 = Caucasian and 0 = non-Caucasian.

For sexual status, 1 = sexually experienced and 0 = sexually inexperienced.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

FIGURE 1.

Sexual status as a moderator of Coping Motives on alcohol-related nonsexual consequences.

Discussion

Sexually experienced first-year college females drank more often and larger quantities during the month transitioning into college than did their sexually inexperienced peers. This finding is consistent with previous research showing correlations between sexual activity and alcohol use (Brown & Vanable, 2007; Leigh & Schafer, 1993; Parks et al., 2008). Also consistent with past studies, sexual experienced individuals yielded higher levels of both drinking motives and alcohol expectancies (Carey, 1995; Thombs et al., 1997; Wilsnack, 1991). However, the current findings extend existing literature, which has focused primarily on alcohol-related sexual harm, by revealing that among incoming college women sexual status is a significant and unique predictor of alcohol-related nonsexual consequences, over and above amount of alcohol consumed. Furthermore, after controlling for drinking, sexual status moderated the predictive relationship between coping motives and nonsexual consequences such that among females who endorsed strong coping motives for drinking, sexual experience was associated with significantly greater alcohol-related nonsexual consequences. Results from this study indicate that alcohol risks faced by sexually experienced incoming college females may not be explained by consumption and drinking motives alone, but may be more multifaceted and complex than previously thought.

Several factors may account for why college entrance appears to pose disproportionate alcohol-related nonsexual risks for sexually experienced females, even after controlling for alcohol consumption. First, compared to sexually inexperienced peers, sexually experienced women may be more inclined to embrace impulsive or sensation-seeking personal styles, which are linked to greater alcohol intake and negative consequences (Baer, 2002; Jackson, Sher, & Park, 2005; Johnson, 1989; Zuckerman & Como, 1983). Pressures to acquire a network of friends amid collegiate cultures in which underage drinking is widespread may be particularly risk enhancing for sexually experienced young women who may be drawn toward risky drinking situations and reckless decision making, whether sexual or nonsexual. In contrast, even if drinking at similar rates, sexually inexperienced women may be less susceptible to drinking-related nonsexual consequences, as they may be influenced to avoid unsafe drinking environments and behaviors per the same protective beliefs that guide them in their sexual abstention. Thus, distinctive personalities of sexually experienced and sexually inexperienced women may contribute to differential drinking circumstances and behaviors associated with varying levels of risk, irrespective of amount consumed. Interventions taking place shortly after matriculation may benefit from assessing personality traits associated with first-year college women's sexual status, which may give rise to risky drinking and adverse nonsexual consequences during challenging transitions. Intervention efficacy may be contingent on effectively communicating ways to deal with stressors and avoid unsafe drinking situations that may be enticing for women possessing particular personality traits.

In addition to dispositional factors, the current results suggest that preexisting patterns of behavior may play a significant role in sexually experienced women's disproportionate drinking-related nonsexual risks. On average, sexually experienced participants had sex for the first time at 16.50 (SD = 1.12) years of age, likely prior to college entrance. The likelihood that pre-established patterns of alcohol and sexual risk-taking behaviors may carry over into college contexts has been supported in several studies (Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1995; Bailey, Fleming, Hensen, Catalano, & Haggerty, 2008; Yu & Shacket, 2001). In this regard, preventive initiatives targeting high school students may be necessary to prevent or minimize risky patterns of behavior. Considering also that college environments have demonstrated catalytic effects on prior drinking behaviors and problems (Yu & Shacket, 2001), it may be helpful to supplement high school-based preventive efforts with collegiate interventions aimed to coincide with newly matriculated students' unprecedented gains in freedom from adult supervision and acclimations to intensified drinking cultures.

In addition, the current findings provide further evidence that coping-motivated drinking, which indicates a dependence on alcohol as a means to resolve psychological issues, is a significant risk factor for first-year college women, over and above alcohol intake and regardless of sexual status (Kassel et al., 2000; Simons et al., 2000; Windle & Windle, 1996). However, while it is not surprising that incoming college students may turn to alcohol to cope with stressful situations that may arise in new college settings, it is notable that sexually experienced participants endorsed more coping-motivated drinking than their sexually inexperienced peers. Moreover, coping motives interacted with sexual status such that among participants endorsing strong coping motives for drinking, sexually experienced women faced significantly more hazardous nonsexual outcomes than sexually inexperienced peers. Considering that coping-motivated drinking is strongly associated with negative consequences, over and above alcohol consumption (Kassel et al., 2000; Simons et al., 2000; Windle & Windle, 1996), and that sexual experience was predictive of drinking and nonsexual problems among this sample, it is possible that both coping-motivated drinking and sexual experience may produce heightened risks for alcohol-related consequences. Thus, the significant interaction that emerged may suggest a synergistic relationship, such that the two risk factors together may predict elevated risk. Challenging college transitions in which both sex and alcohol are prominent aspects of social life may worsen inefficient coping behavior and further perpetuate problems. Conversely, sexually experienced women who do not drink to cope likely possess better overall psychological competence, denoting healthy perspectives toward both drinking and sexual relations, and less reckless drinking behavior compared to coping motivated sexually experienced counterparts. While much is known of college students' social motives for drinking, coping-based rather than social-based motives were associated with increased alcohol-related consequences even after controlling for drinking in this sample. This is similar to findings across other samples of college students that did not just include first-year women (e.g., Windle & Windle, 1996). Campus support programs for incoming first-year college women, particularly those who are sexually experienced, are warranted to help at-risk female students better understand how they might be inclined to use alcohol to cope with challenging transitional periods as well as minimize dependency on coping-based drinking.

Limitations

When interpreting these results, some methodological limitations should be considered. First, given the present findings, examining the risk associated with the degree of sexual experience (i.e., number of sexual partners), participants' affiliation to past sexual partners or type of past sexual relationships may offer important insight into the impact of sexual activity status on collegiate alcohol-related risk. Differentiating monogamous from casual sex would be constructive as both number of partners and partner type may play a role in one's social and drinking behaviors. In all likelihood, sexually experienced young women with histories of monogamous sex may require greater familiarity of potential sexual partners, may drink in safer contexts, and may exhibit more prudent drinking-related decision making than sexually experienced peers prone to casual sex who may be less discriminate in mate selection, drinking situations, and drinking-related judgment. Also, even though our investigation illustrates sexually experienced women's heightened risks for alcohol consumption and related negative consequences during the transition to college, longitudinal analyses assessing women's drinking and sexual behavior through the college years may highlight vital prospective patterns. Not only might this reflect participants' sexual behavioral changes but it also may expose changing perceptions toward sexual activity, which are found to become increasingly more liberal and decreasingly less fearful through college (i.e., fear of pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, negative societal labels; Gilmartin, 2006). In sum, determining college women's past and present sexual affiliations, intentions, and personal beliefs may shed light on likely drinking-related expectancies, motives, and behavioral risks, thereby strengthening intervention efficacy. Furthermore, this study assessed only the relationship between sexual status and drinking-related variables in women. Future research will want to explore if similar patterns hold for college males, particularly during their transition into college. Finally, although careful measures were taken to assure participants that the surveys were confidential, social desirability bias is always an inherent risk of self-reports, particularly those pertaining to sexual behavior.

Conclusion

Early collegiate experiences have been shown to have considerable and enduring influence on long-term drinking trajectories (NIAAA, 2002). The current study makes several contributions to the literature of women's alcohol use during this critical life stage by supporting that sexually experienced females transitioning into college appear to face elevated risks for experiencing alcohol-related nonsexual consequences compared to their sexually inexperienced peers, even when controlling for alcohol use. More specifically, results emphasize the unique dangers of using alcohol to cope with personal problems, particularly for sexually experienced women. It appears that prior and/or current sexual activity contributes to alcohol-related nonsexual consequences that cannot be attributed to increased alcohol consumption alone, but rather sexual status may alter drinking experiences in harmful ways, perhaps via impulsive personality characteristics or as an extension of behavioral patterns established prior to college entrance. The present findings offer support for high school-based preventative efforts as well as college-based early intervention strategies targeted toward sexually experienced young women as they transition to college. Moreover, given that alcohol-related negative consequences were found to be both nonsexual and independent of levels of consumption, it is vital to convey to at-risk women how they may be prone to alcohol-related risk-taking behavior that extends beyond amount of alcohol consumed. Still, while the present findings offer valuable insight into how sexually experienced incoming college females may be predisposed to adverse consequences, additional research is needed to further understand how sexual status may influence the etiology of risky drinking-related behaviors in order to develop programs and initiatives aimed at limiting the negative outcomes associated with such risk factors.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant U18 AA15451-01.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alan Guttmacher Institute. Sex and America's teenagers. New York: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Annis HM, Sklar SM, Moser AE. Gender in relation to relapse crisis situations, coping, and outcome among treated alcoholics. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23(1):127–131. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Sensation seeking, aggressiveness, and adolescent reckless behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 1996;20(6):693–702. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. Smoking, drinking and drug use in young adulthood: The impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Student factors: Understanding individual variation in college drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14(Suppl):40–53. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. High-risk drinking across the transition from high school to college. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19(1):54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Fleming CB, Hensen JN, Catalano RF, Haggerty KP. Sexual risk behaviors 6 months post-high school: Associations with college attendance, living with a parent, and prior risk behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42(6):573–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz AD, Perkins HW. Recent research on gender differences in collegiate alcohol use. Journal of American College Health. 1987;36(3):123–126. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1987.9939003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof G, Rumpf HJ, Meyer C, Hapke U, John U. Gender differences in temptation to drink, self-efficacy to abstain and coping behavior in treated alcohol-dependent individuals: Controlling for severity of dependence. Addiction Research & Theory. 2005;13(2):129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Vanable PA. Alcohol use, partner type, and risky sexual behavior among college students: Findings from an event-level study. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(12):2940–2952. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB. Alcohol-related expectancies predict quantity and frequency of heavy drinking among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1995;9(4):236–241. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, Hasin DS. Drinking to cope with negative affect and DSM-IV alcohol use disorders: A test of three alternative explanations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(5):694–704. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASA: The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. The formative years: Pathways to substance abuse among girls and young women ages 8–22. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(2):117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Agocha VB, Sheldon MS. A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. Journal of Personality. 2000;68(6):1059–1088. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(5):990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97(2):168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley JE. Educational status and drinking patterns: How representative are college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52(1):10–16. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Division of Adolescent & School Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance: National college health risk behavior survey—United States, 1995. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 1997;46(S–S6):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engs RC, Diebold BA, Hanson DJ. The drinking patterns and problems of a national sample of college students, 1994. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1996;41(3):13–33. [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Frone MR, Cooper ML, Russell M. A revised Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire: Factor structure confirmation and invariance in a general population sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56(2):177–185. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin SK. Changes in college women's attitudes toward sexual intimacy. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(3):429–454. [Google Scholar]

- Gleason NA. College women and alcohol: A relational perspective. Journal of American College Health. 1994;42(6):279–289. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1994.9936360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomberg ESL. Risk factors for drinking over a woman's life span. Alcohol Health & Research World. 1994;18(3):220–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JA. Psychological separation of late adolescents from their parents. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1984;31(2):170–178. [Google Scholar]

- Holdcraft LC, Iacono WG. Cohort effects on gender differences in alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2002;97:1025–1036. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Park A. Drinking among college students: Consumption and consequences. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent developments in alcoholism, vol 17: Alcohol problems in adolescents and young adults. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 85–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PB. Personality correlates of heavy and light drinking female college students. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1989;34(2):33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2002. 2001 (NIH Publication 02-5105) [Google Scholar]

- Jones BM, Jones MK. Women and alcohol: Intoxication, metabolism and the menstrual cycle. In: Greenblatt M, Schuckit MA, editors. Alcoholism problems in women and children. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1976. pp. 103–136. [Google Scholar]

- Karwacki SB, Bradley JR. Coping, drinking motives, goal attainment expectancies and family models in relation to alcohol use among college students. Journal of Drug Education. 1996;26(3):243–255. doi: 10.2190/A1P0-J36H-TLMJ-0L32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Jackson SI, Unrod M. Generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation and problem drinking among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(2):332–340. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knibbe R, Drop M, Muytjens A. Correlates of stages in the progression from everyday drinking to problem drinking. Social Science and Medicine. 1987;24:463–473. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90221-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Engels R, Gmel G. Bullying and fighting among adolescents: Do drinking motives and alcohol use matter? Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(12):3131–3135. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(7):841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie E, Bates ME. Reasons for alcohol use in young adulthood: Validations of three-dimensional measures. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(2):145–155. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Huchting K, Tawalbeh S, Pedersen ER, Thompson AD, Shelesky K, et al. A randomized motivational enhancement prevention group reduces drinking and alcohol consequences in first-year college women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:149–155. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C. Self-consciousness moderates the relationship between perceived norms and drinking in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(12):1529–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Pedersen ER. Reasons for drinking in the college student context: The differential role and risk of the social motivator. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(3):393–398. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Thompson AD, Ferraiolo P, Garcia JA, Huchting K, Shelesky K. The differential impact of relational health on alcohol consumption and consequences in first-year college women. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(2):266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapsley DK, Rice KG, Shadid GE. Psychological separation and adjustment to college. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1989;36(3):286–294. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh B, Schafer JC. Heavy drinking occasions and the occurrence of sexual activity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1993;7:197–200. [Google Scholar]

- MacLean MG, Lecci L. A comparison of models of drinking motives in a university sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:83–87. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. A call to action: Changing the culture of drinking at U S colleges. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol and Abuse and Alcoholism; 2002. NIH Publication 02-5010. [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill SE, Parra GR, Sher KJ. Clinical relevance of heavy drinking during the college years: Cross-sectional and prospective perspectives. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:350–359. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Armeli S, Tennen H. The daily stress and coping process and alcohol use among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(1):126–135. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Romosz AM, Bradizza CM, Ya-Ping H. A dangerous transition: Women's drinking and related victimization from high school to the first year at college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:65–74. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, LaBrie JW. Normative misperceptions of drinking among college students: A look at the specific contexts of prepartying and drinking games. Journal of Studies on Alcohol & Drugs. 2008;69(3):406–411. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins WH. Research on women's drinking patterns: Q&A with Wes Perkins. Catalyst. 2000;6:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Presley CA, Meilman PW, Leichliter JS. College factors that influence drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14(Suppl):82–90. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullen LM. The relationship among alcohol abuse in college students and selected psychological/demographic variables. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1994;40(1):36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Randall CL, Roberts JS, Del Boca FK, Carroll KM, Connors GJ, Mattson ME. Telescoping of landmark events associated with drinking: A gender comparison. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(2):252–260. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Rutledge PC. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: Predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(4):819–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons J, Correia CJ, Carey KB. A comparison of motives for marijuana and alcohol use among experienced users. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25(1):153–160. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS, Hunt-Carter EE, Nabors-Oberg RB, Sher KJ, Bucholz KK, Madden PAF, et al. Do college students drink more than their non-college-attending peers? Evidence from a population-based longitudinal female twin study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(4):530–540. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Loughlin HL, Rhyno E. Internal drinking motives mediate personality domain—drinking relations in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, Wolcott BJ, Farkash LGE. Social context, perceived norms and drinking behavior in young people. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:257–267. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C. The 8-year course of alcohol abuse: Gender differences in social context and coping. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2005;29(4):612–621. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000158832.07705.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vince-Whitman C, Cretella M. Alcohol use by college women: Patterns, reasons, results, and prevention. Catalyst: A publication f the higher education center for alcohol and other drug prevention. 1999;5:4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B. Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college: A national survey of students at 140 campuses. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272(21):1672–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990s: A continuing problem: Results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48(5):199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts: Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys, 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50(5):203–317. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Nelson TF, Kuo M. Underage college students' drinking behavior, access to alcohol, and the influence of deterrence policies: Erratum. Journal of American College Health. 2002;51:37. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Moeykens B, Davenport A, Castillo S, Hansen J. The adverse impact of heavy episodic drinkers on other college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56(6):628–634. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TF. What we have learned from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study: Focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. Journal of Studies on Alcohol & Drugs. 2008;69:1–10. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westmaas J, Moeller S, Woicik PB. Validation of a measure of college students' intoxicated behaviors: Associations with alcohol outcome expectancies, drinking motives, and personality. Journal of American College Health. 2007;55(4):227–237. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.4.227-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50(1):30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, McMorris BJ, Catalano RF, Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, Abbot RD. Increases in alcohol and marijuana use during the transition out of high school into emerging adulthood: The effects of leaving home, going to college, and high school protective factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:810–822. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC. Sexuality and women's drinking: Findings from a U.S. national study. Alcohol Health & Research World. 1991;15(2):147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Windle RC. Coping strategies, drinking motives, and stressful life events among middle adolescents: Associations with emotional and behavioral problems and with academic functioning. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105(4):551–560. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Shacket RW. Alcohol use in high school: Predicting students' alcohol use and alcohol problems in four-year colleges. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27(4):775–793. doi: 10.1081/ada-100107668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M, Como P. Sensation seeking and arousal systems. Personality and Individual Differences. 1983;4(4):381–386. [Google Scholar]