Abstract

Background

Tetraspanins are transmembrane proteins that serve as scaffolds for multiprotein complexes containing, for example, integrins, growth factor receptors and matrix metalloproteases, and modify their functions in cell adhesion, migration and transmembrane signaling. CD151 is part of the tetraspanin family and it forms tight complexes with β1 and β4 integrins, both of which have been shown to be required for tumorigenesis and/or metastasis in transgenic mouse models of breast cancer. High levels of the tetraspanin CD151 have been linked to poor patient outcome in several human cancers including breast cancer. In addition, CD151 has been implicated as a promoter of tumor angiogenesis and metastasis in various model systems.

Methods

Here we investigated the effect of Cd151 deletion on mammary tumorigenesis by crossing Cd151-deficient mice with a spontaneously metastasising transgenic model of breast cancer induced by the polyoma middle T antigen (PyMT) driven by the murine mammary tumor virus promoter (MMTV).

Results

Cd151 deletion did not affect the normal development and differentiation of the mammary gland. While there was a trend towards delayed tumor onset in Cd151−/− PyMT mice compared to Cd151+/+ PyMT littermate controls, this result was only approaching significance (Log-rank test P-value =0.0536). Interestingly, Cd151 deletion resulted in significantly reduced numbers and size of primary tumors but did not appear to affect the number or size of metastases in the MMTV/PyMT mice. Intriguingly, no differences in the expression of markers of cell proliferation, apoptosis and blood vessel density was observed in the primary tumors.

Conclusion

The findings from this study provide additional evidence that CD151 acts to enhance tumor formation initiated by a range of oncogenes and strongly support its relevance as a potential therapeutic target to delay breast cancer progression.

Keywords: Tetraspanin, CD151, Breast, Cancer, Metastasis

Background

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among women and despite some major advances in diagnosis and treatment, it remains the second leading cause of cancer death in women worldwide. Similarly to other cancers, some of the major challenges in the treatment of breast cancer reside in the lack of response or development of resistance to existing therapies and the devastating consequences of metastasis. Better prognostic markers as well as new targeted treatments that could be used alone, or most likely in combination with existing therapies are needed to improve patient outcomes.

The tetraspanin CD151 is part of the tetraspanin family of transmembrane proteins, which consists of 33 members in humans. These proteins serve as scaffolds for multiprotein complexes (called TEMs or Tetraspanin-Enriched Microdomains) where they associate with molecules such as integrins, growth factor receptors and matrix metalloproteases, modifying their functions in various cellular processes. CD151 forms tight complexes with the laminin binding integrins (α3β1, α6β1 and α6β4) [1], modulates their signaling and contributes to integrin mediated cell adhesion and motility.

Interestingly, β1-integrin and β4-integrin- heterodimers (reviewed in [2]) are both expressed by breast epithelial cells (mostly as α3β1 and α6β4) and have been shown to be required for tumorigenesis and metastasis in the MMTV/PyMT and MMTV/Neu (rat homolog of ErbB2) mouse models of breast cancer [3,4], respectively. CD151 expression itself has been associated with poor patient outcome in several malignancies, including cancers of the breast [5,6], prostate [7], lung [8], and kidney [9], whereas it has also been found to correlate with improved survival in endometrial cancer [10]. Notably in breast cancer, elevated expression of CD151 correlates with lymph node invasion and poor overall survival of patients with invasive ductal carcinoma [5,6]. In accordance with its association with poor prognostic in patients, CD151 has been implicated as a promoter of tumor angiogenesis and/or metastasis in vitro in human breast cancer cell lines and in several in vivo model systems including xenografts [5,11], matrigel plug and tumor implantation experiments [12], as well as experimental metastasis models [13,14]. In addition, a recent study showed that CD151 plays a role in mammary cell proliferation, suggesting the involvement of CD151 in tumor cell growth [15].

Altogether these data strongly indicate a role for CD151 in tumor growth and metastasis, suggesting that it could be used as a target molecule for the design of new breast cancer therapies. However, when we started this work, the possible direct cause-effect relationship between CD151 expression and breast tumor onset/progression and metastasis had never been tested. In order to address this question, we studied the effect of Cd151 deletion on de novo breast tumorigenesis and spontaneous metastasis in the very well characterized MMTV/PyMT transgenic breast cancer mouse model [16]. In this model, the polyoma middle T oncogene is expressed under the transcriptional control of the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter. The mammary tumors that develop in MMTV/PyMT female mice recapitulate the histological stages of human breast cancer from premalignant lesions to invasive carcinoma [17] and they also display activation of the same signaling pathways that act downstream of the ErbB2 oncogene and are often activated in breast cancer, such as c-Src, PI3K and Ras [18].

It is interesting to note that a study addressing the impact of Cd151 deletion in another mouse model of breast cancer (the ErbB2 model) has recently been published by Deng and colleagues [19]. The results from both studies will be compared in the discussion.

Here we show that Cd151–null mice develop smaller and fewer PyMT mammary tumors than their age matched controls. Our results suggest that Cd151 deletion impairs tumor initiation and/or tumor growth in the MMTV/PyMT model, while an apparent effect on tumor metastasis could be attributable to larger tumor burden in Cd151+/+ mice.

Methods

Experimental animals

Animal maintenance was in accordance with the Animal Care and Ethics Committee at the Australian BioResources specific pathogen free (SPF) animal breeding facility (Moss Vale, New South Wales). All animal monitoring and experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee at the University of Newcastle. In the tumorigenesis experiments, we used the well-characterized FVB/N (FVB) MMTV/PyMT mouse line (MT#634) carrying a mouse mammary tumor virus promoter-driven polyoma middle T transgene [16]. A pure FVB genetic background is most commonly used for mouse tumorigenesis experiments because of its permissiveness to spontaneous tumor development. Cd151−/− mice are grossly healthy on the C57Bl/6 (B6) background [20] but they develop a severe kidney disease on a pure FVB background [21]. Hence FVB Cd151−/− mice could not be used for the tumorigenesis experiments. Since F1 hybrid FVB x B6 Cd151−/− mice were healthy and did not present any sign of kidney disease onset (monitored for the appearance of proteinuria over a 12 months period, our unpublished data), we conducted the experiments on this hybrid background. This allowed us to keep all experimental animals on a mixed but yet homogenous (50% B6 and 50% FVB) genetic background. FVB Cd151+/− mice were produced by backcross for 10 generations from the original B6 Cd151−/−[20] and maintained as heterozygotes. Heterozygous B6 Cd151+/− females were crossed with FVB Cd151+/− males carrying the MMTV/PyMT transgene (PyMT Cd151+/− males, see Additional file 1: Figure S1 for breeding details) in order to generate the experimental F1 animals. Genotyping was performed as previously described [20]. Experimental and control littermates were co-housed throughout the experiments, in a temperature controlled facility with a 12-h light: dark cycle.

Animal monitoring and tissue collection

Beginning at weaning (3 weeks of age), female mice were palpated twice weekly for the onset of mammary tumors. For each mouse, tumor palpation was performed in each of the ten mammary glands, in a genotype-blinded fashion. At 15–16 weeks of age, female mice were euthanased by CO2 inhalation, and all the tumors were dissected and weighed. For each experimental mouse, half of the biggest tumor was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) for paraffin embedding, one quarter was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and the last quarter was snap frozen in OCT compound. At the time of dissection and after excision of the tumors, the lungs were exposed and inflated via tracheal injection of 1 ml of 10% NBF in order to inflate and fix the lung lobes. Lungs were then excised and further fixed in 10% NBF for at least 24 hours before paraffin embedding.

Whole mount analysis

Whole mount analysis was performed by spreading inguinal #4 mammary glands onto poly-lysine slides followed by overnight fixation in 10% NBF, defatting in acetone and overnight staining in carmine alum (0.2% carmine and 0.5% aluminium sulphate) as previously described [22]. The stained glands were then dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, incubated in xylene for 1 hour and stored in methyl salicylate.

Tumor histology and immunohistochemistry

Tumor histology/stage was assessed on the largest tumor for each mouse using 5 μm paraffin sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on 5 μm paraffin sections using a peroxidase VECTASTAIN ABC elite kit and DAB peroxidase substrate kit as per the manufacturer’s recommendations (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The antibodies and dilutions used for IHC were rabbit monoclonal anti-Ki67 at 1:200 (Neomarkers, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) and polyclonal rabbit anti-cleaved caspase 3 at 1:800 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA).

Immunofluorescence labeling

Immunofluorescence labelings were performed on 5 μm frozen sections as previously described [21]. Primary antibodies and dilutions used for immunofluorescence labeling were rabbit anti-CD151 (LAI-2) at 1:500 [21]; rat anti-CD31 (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at 1:200; rabbit anti-α3 integrin (a kind gift from Dr. Fiona Watt, Wellcome Trust Centre for Stem Cell Research, Cambridge, UK) at 1:1000; rat anti-β1 integrin (BD Biosciences) at 1:200; rat anti-β4 integrin (BD Biosciences) at 1:200; rat anti- α6 integrin (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA) at 1:200. The double labeling where two rabbit primary antibodies were used (CD151 and α3 integrin) was performed sequentially following established methods as described previously [21].

Quantitation of tumor cell proliferation, apoptosis and vascularization

The largest tumor for each mouse was used to quantitate proliferation, apoptosis and vascularization in a genotype-blinded manner. Tumor cell proliferation was assessed by immunohistochemistry (as described above) for the commonly used Ki67 nuclear marker. Ki67 stained slides were scanned in a digital format using the Aperio™ digital pathology system (Aperio) and 200× magnification snapshots of digital images were generated using Imagescope. Quantitation of proliferation (expressed as percent Ki67 positive nuclear area per total nuclear area) was then performed on the 200× digital images using ImmunoRatio, a publicly available web-based application [23]. The extent of apoptosis in the tumors was quantitated on Aperio images of cleaved-caspase 3 IHC stained slides, using the positive pixel count algorithm at 200× magnification (5 fixed size (300 μm × 300 μm) images were used for each tumor section).

To estimate blood vessel density, CD31 immunofluorescence labeling was performed and Image J was used to quantitate the proportion of CD31 positive area inside the tumors. At least five fluorescent microscope pictures (100× magnification) per tumor were used in the CD31 analysis.

Analysis of lung metastasis

All the lung lobes were dissected and processed for paraffin embedding. Five microns paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and slides were scanned in a digital format using the Aperio™ digital pathology system (Aperio). The lung area per section was measured using Scanscope and the metastatic burden (mm2 of metatastases/cm2 lung) was calculated for each animal, using the data from 3 sections at least 100 μm apart, as previously described [24].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism 6 (Graphpad software). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analysed with the log-rank test. Metastasis distribution was assessed with a contingency table and Chi-square test. All the other data sets were submitted to the Shapiro-Wilk normality test and depending on the result of this test, parametric or non-parametric comparison tests were performed. Specific tests used for each data set are mentioned in the figure legends. In all tests, P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Deletion of Cd151 does not interfere with mammary gland development and differentiation

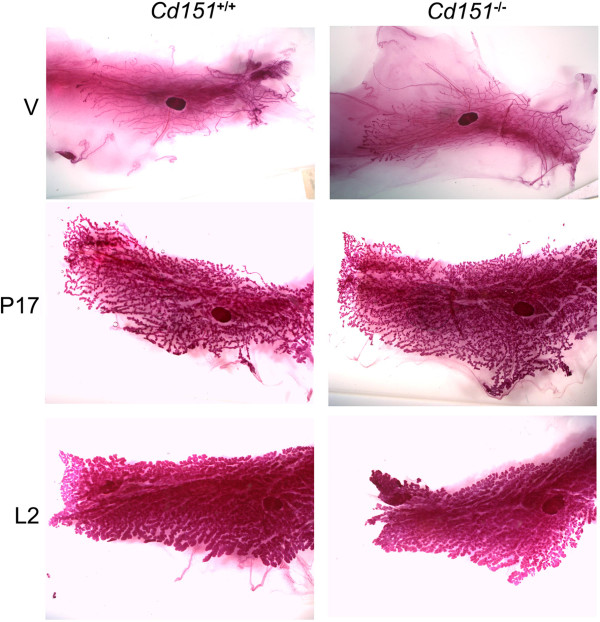

Before investigating the effect of Cd151 deletion on mammary tumorigenesis it was necessary to determine whether mammary gland development and differentiation was normal in Cd151 knock-out mice. For this purpose, we performed whole mount analysis of #4 inguinal mammary glands in virgin, pregnant and lactating FVB Cd151+/+ and Cd151−/− mice (Figure 1). Ductal outgrowth and mammary gland differentiation appeared grossly normal in the Cd151−/− females at the different stages of development investigated.

Figure 1.

Whole mount analysis of mammary gland development in Cd151+/+ and Cd151 −/− mice. The morphology of whole mount #4 mammary glands was analysed at different stages in FVB Cd151+/+ and Cd151−/− mice. Mammary gland development was assessed in virgin glands (V, top panel) and appeared to occur normally in Cd151−/− animals as compared to Cd151+/+ mice. Mammary gland differentiation during pregnancy (day 17 of pregnancy, middle panel) and lactation (lactation day 2, bottom panel) was also unchanged in Cd151−/− mice.

Expression pattern of CD151 in the normal mammary gland and PyMT mammary tumors

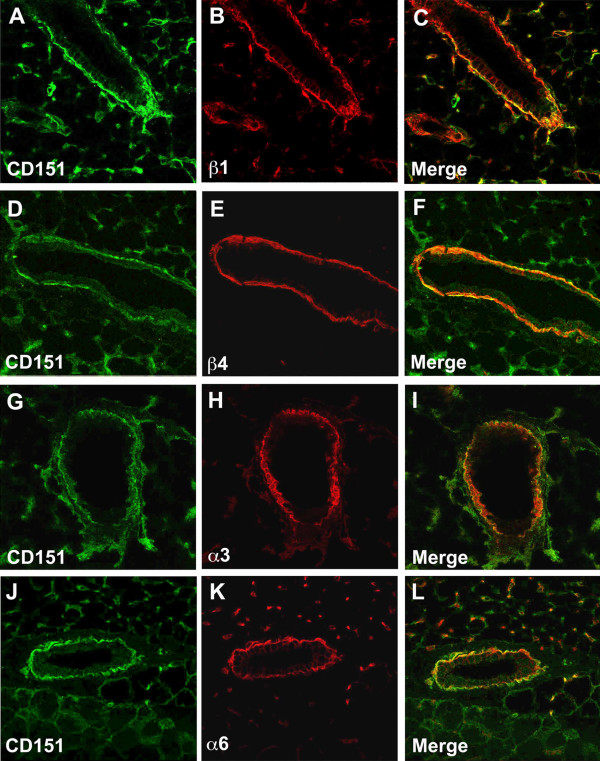

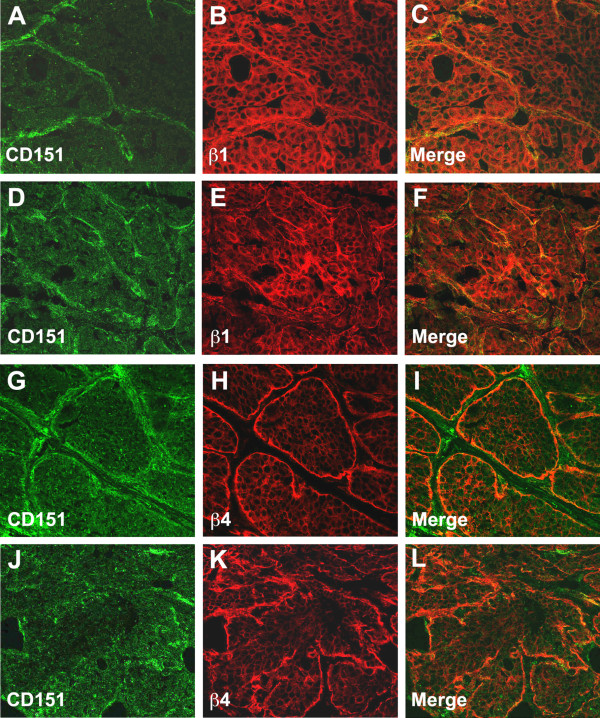

Immunofluorescence labeling of 6-week old virgin mammary glands and confocal microscopy revealed strong expression of CD151 in the mammary ducts in a basolateral pattern (Figure 2), reminiscent of the surrounding basal layer of myoepithelial cells and in accordance with what has been previously reported in humans [11]. Fainter CD151 labeling was also noticeable in the basolateral membrane of ductal luminal cells (Figure 2A). Moreover, CD151 labeling in the mammary ducts colocalized to some extent with the α3-, α6-, β1- and β4- chains of integrins, suggesting association of CD151 with the α3β1, α6β1 and α6β4 integrin heterodimers in the mammary gland. Similarly to the situation in the normal glands, CD151 appeared to be expressed strongly by the myoepithelial cell layer surrounding the tumor nodules of the early stage PyMT tumors, while the cancer cells in the nodules were only faintly labeled (Figure 3). The CD151 labeling overlapped to some extent with the β1- and β4- integrin immunolabelings in the tumors suggesting as expected some degree of colocalization.

Figure 2.

Localization of CD151 in the wild-type mouse mammary gland. Dual immunofluorescent labeling and confocal analysis using CD151 antibodies (green) and antibodies towards the integrin chains β1 (A-C), β4 (D-F), α3 (G-I) and α6 (J-L) in red. CD151 co-localizes with these 4 chains of integrins in the basal cell layer of the mammary epithelium and the basolateral membrane of luminal epithelial cells. Original magnification ×400.

Figure 3.

Expression of CD151 in mammary tumors. Dual immunofluorescent labeling and confocal analysis using CD151 antibodies (green) and antibodies towards β1-(A-F), or β4-integrin (G-L) were performed on Cd151+/+ MMTV/PyMT mammary tumors at the adenoma stage (A-C and G-I) and the carcinoma stage (D-F and J-L) (stages as defined by Lin et al. [17]). At the early adenoma stage (A-C and G-I), the tumor cells showed faint CD151 expression overall that was more intense on the edge of the tumor nodules, colocalizing with β1 and β4 integrins along the basement membrane. At a more advanced tumor stage, the labeling was more patchy with still some degree of colocalization with integrins (D-F and J-L). Original magnification ×400.

Loss of Cd151 significantly decreases mammary tumor multiplicity and growth

To avoid the kidney phenotype that has been described in FVB Cd151−/− mice [21], we chose to investigate the effects of Cd151 deletion on mammary tumorigenesis on a F1 (FVB×B6) background (see explanations in Methods). Consistent with previous reports showing increased PyMT tumor latency on the B6 background [24,25], the onset of mammary tumors was significantly delayed by about 20 days on the (FVBxB6) F1 background in comparison to the pure FVB background (Additional file 2: Figure S2).

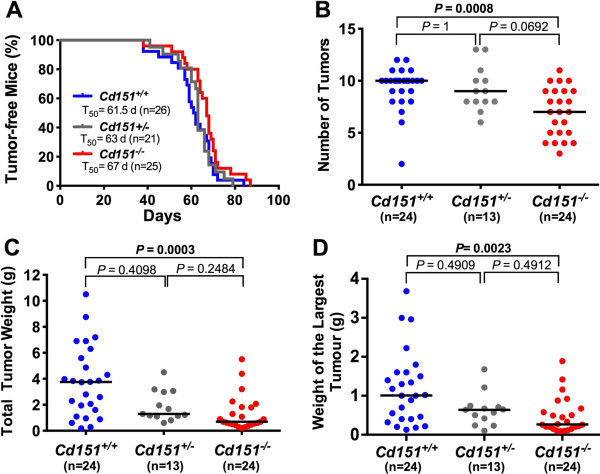

Investigation of mammary tumor onset by palpation showed no statistically significant difference in tumor latency between Cd151+/+ and Cd151−/− PyMT mice (Figure 4A). There was however a trend towards increased tumor latency in Cd151−/− (T50 = 67 days; n = 25) as compared to Cd151+/+ (T50 = 61.5 days; n = 26) that was approaching significance (Log-rank test P-value =0.0536). Interestingly, the median age to tumor onset in the heterozygous Cd151+/− mice was in between the values reported for Cd151+/+ and Cd151−/− PyMT mice (Cd151+/− T50 = 63, n = 21). However, the difference between the median tumor latency of Cd151+/− versus Cd151+/+ mice was not significant (Log-rank test P = 0.7533).

Figure 4.

Effect of Cd151 deletion on MMTV/PyMT tumor onset and growth. (A) The appearance of mammary tumors was monitored in MMTV/PyMT Cd151+/+, Cd151+/− and Cd151−/− mice by bi-weekly palpation and is represented on a Kaplan-Meier survival curve. T50 indicates the median time to development of a palpable mammary tumor for each group of mice. The differences in T50 between Cd151+/+ and Cd151−/− groups or between the Cd151+/+ and the Cd151+/− groups were not statistically significant (log rank test P = 0.0536 and P = 0.7533, respectively). Tumor multiplicity (B), total tumor weight (C) and the weight of the biggest tumor per mouse (D) were measured at the time of euthanasia. The horizontal bars on the graphs represent the median for each parameter. The results were compared using the non-parametric Krustal-Wallis test. The number of tumors (B, P = 0.0003), the total tumor weight per mouse (C, P = 0.0002) and the weight of the biggest tumor per mouse (D, P = 0.0014) were significantly decreased in the Cd151−/− group compared to the Cd151+/+. mice. There were no significant differences when comparing Cd151+/+ with Cd151+/− groups or Cd151+/− with Cd151−/− respectively.

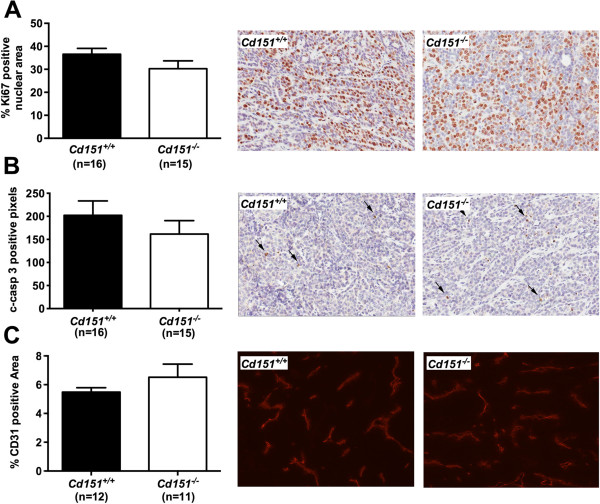

At 15 to 16 weeks of age (i.e. 6 to 7 weeks after initial tumor palpation), the mice were euthanased and all the tumors were collected and weighed for each mouse. Interestingly both the total tumor weight (P = 0.0003) and tumor multiplicity (P = 0.0008) per mouse were significantly decreased in the Cd151−/− group as compared to Cd151+/+ group (Figure 4B and 4C). Individual tumor weight (as shown with weight of the largest tumor per mouse Figure 4D) was also clearly decreased in Cd151−/− mice (P = 0.0023), suggesting an effect of Cd151 gene deletion on both mammary tumor induction and growth/proliferation in vivo. Regardless of the Cd151 genotype, at least part of the largest tumor of each mouse had progressed to the carcinoma stage as determined by H&E staining (illustrated in Figure 5). Immunolabelings for Ki67, cleaved caspase-3 and CD31 were performed on representative primary tumor samples in order to compare the rates of cell proliferation, apoptosis and tumor angiogenesis between both groups of mice, respectively (Figure 6). These experiments did not reveal any significant differences between Cd151+/+ and Cd151−/− tumors.

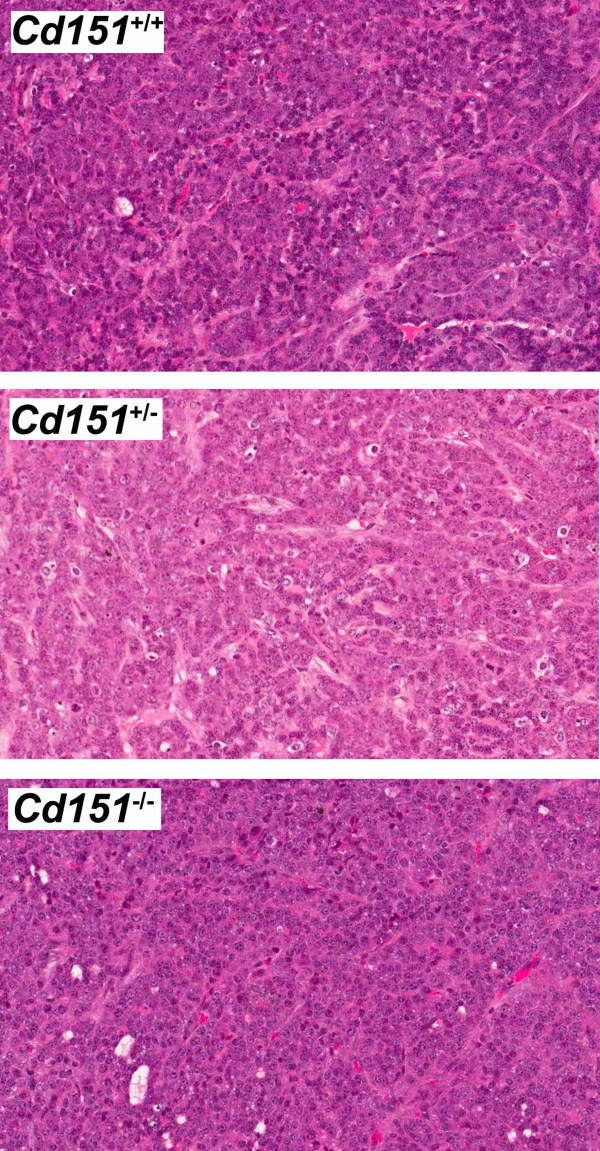

Figure 5.

Tumor histology of the MMTV/PyMT Cd151+/+, Cd151+/− and Cd151−/− mice. At the end point, tumor histology (assessed by H&E staining) was undistinguishable between the three groups of mice. All mammary tumors presented features of the carcinoma stage, independently of their Cd151 genotype.

Figure 6.

Tumor cell proliferation, apoptosis and blood vessel density in Cd151+/+ and Cd151−/− mammary tumors. These parameters were assessed by IHC for the cell proliferation marker Ki67 (A, P =0.1533), the apoptosis marker cleaved-caspase 3 (B, P =0.3476), and by immunofluorescence for the endothelial cell specific antigen CD31 (C, P = 0.3035), respectively. Means ± SEM are represented and parametric t-test was used to compare the data. Representative photos of the immunolabelings are also shown. Original magnification: ×200 for Ki67 and Cleaved-caspase 3 and ×100 for CD31.

Effect of Cd151 deletion on development of lung metastases

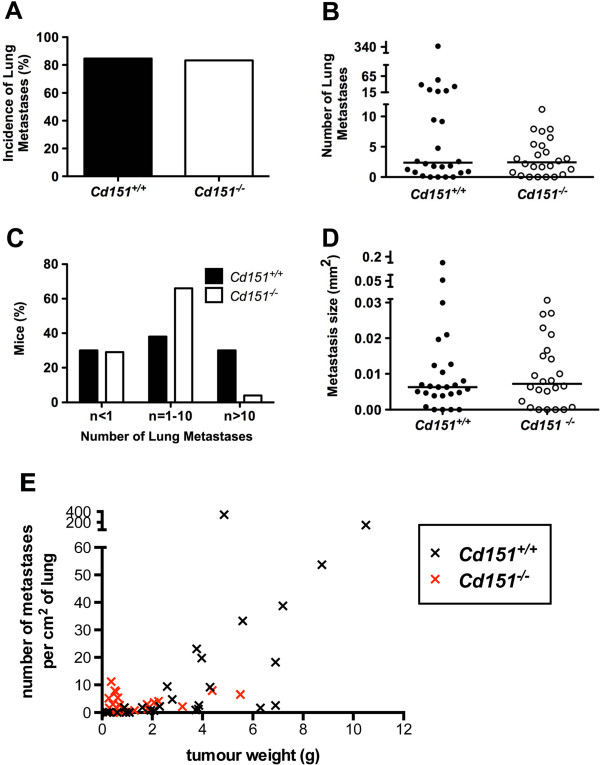

Since the mammary tumors of MMTV/PyMT mice primarily metastasize to the lungs, we examined the lungs of Cd151+/+ and Cd151−/− PyMT mice at the time of dissection, which corresponds to 6 to 7 weeks after tumor onset. The incidence of lung metastasis was similar in both groups with 22 out of 26 Cd151+/+ (85%) and 20 out of 24 Cd151−/− (83%) mice developing lung metastases (Figure 7A). In addition, the median number of lung metastases (Mann Whitney test P-value = 0.3554) and the average size of individual metastasis per mouse (Mann Whitney test P-value = 0.6757) were similar between the two groups (Figure 7B and 7D, respectively). The distribution of the number of metastases in the Cd151+/+ group, was much more heterogeneous (Figure 7B), with a large subset of the Cd151+/+ but not Cd151−/− group of mice containing high numbers of metastases (Chi-square P-value = 0.0329, Figure 7C). On closer observation, it could be noted that the mice with high number of metastases in the Cd151+/+ group were also the mice with higher tumor burden (Figure 7E) suggesting that tumour burden rather than Cd151 status is the likely explanation. In conclusion, ablation of Cd151 per se did not appear to affect the number or size of metastases in the MMTV/PyMT mice.

Figure 7.

Impact of Cd151 deletion on lung metastases. The incidence of lung metastasis (A), the median number of lung metastases (per cm2) per mouse (B, P = 0.3554), and the average metastasis size per mouse (mm2) (D, P = 0.6757) were not different between Cd151+/+ (n = 26) and Cd151−/− (n = 24) mice. Non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the data in B and D and the horizontal bars indicate the median values. The distribution of the number of metastases per mouse was much more heterogenous in the Cd151+/+ group (C): A significantly larger proportion of Cd151+/+ (8/26) than Cd151−/− (1/24) mice had 10 or more metastatic foci per cm2 of lung (Chi square P value = 0.0329). (E) Correlation between the number of metastases and the total tumor weight per mouse was assessed using the non parametric Spearman correlation test. The number of metastases did not correlate with tumor burden in the Cd151−/− group (r = 0.117, P = 0.5861). There was however a strong correlation between number of metastases and tumor weight in the Cd151+/+ group (r = 0.8046, P < 0.0001), which contains mice with larger tumor burden than the Cd151−/− group.

Discussion

In this study, we found that deletion of Cd151 significantly impaired tumor development and progression in the murine MMTV/PyMT breast tumorigenesis model. These results are consistent with previous work investigating CD151’s function in other breast tumor models, suggesting that regardless of the tumor initiating oncogene, CD151 enhances tumor initiation and subsequent progression. Whilst the increase in tumor latency in Cd151−/− mice was only approaching significance, there was significant decrease in the number of tumors per mouse, suggesting that Cd151 deletion might impair PyMT tumor initiation. This could be determined in future experiments by assessing the early stages of PyMT tumorigenesis (from the age of weaning) and whether the extent of hyperplasia is different between genotypes before a palpable tumor can be detected. The decreased number of detectable tumors could also reflect a pronounced defect in tumor growth. Indeed, the size of the mammary tumors was also reduced in Cd151−/− mice, as shown by the total tumor burden per mouse (expressed as total tumor weight per mouse), as well as the individual tumor weight (represented as the weight of the largest tumor for each mouse). Intriguingly however we did not find a difference in tumor vascularisation or tumor cell proliferation and apoptosis that could explain the decreased tumor size in Cd151−/− mice. In conclusion, the absence of effect on tumor proliferation and apoptosis reinforces the hypothesis stated above that Cd151 deletion may act predominantly by delaying PyMT tumor initiation, as suggested by the trend towards delayed tumor onset and the decreased number of tumors per mouse.

In recent years, Sadej and colleagues have reported a decrease in tumor growth associated with CD151 knock-down in a subcutaneous xenograft model [5]. Similar to our result, CD151 knock-down did not have an effect on overall vessel density in the xenografts. Interestingly however the authors of that study described a pronounced decrease in the dense angiogenic network typically observed at the subcutaneous border of this type of tumors. We were not able to similarly assess the tumor border in our model system due to the nature of the de novo MMTV/PyMT tumors and because rich vascular networks do not develop at the periphery of tumors in this model.

Tumor progression in the MMTV/PyMT model has been very well characterized; it follows several well-defined stages from hyperplasia to non-invasive adenoma and finally invasive carcinoma [17]. Loss of the myoepithelial cell layer surrounding the hyperplastic luminal epithelial structures is an important step in the progression to invasive carcinoma in these tumors [26,17]. Moreover, mammary myoepithelial cells have been referred to as ‘natural tumor suppressors’ because of their capacity to block tumor cell growth and invasion [27,28]. Because CD151 is primarily expressed in the mammary myoepithelial cells and the PyMT tumors arise from luminal epithelial cells in the mammary gland where CD151 has reduced expression, it is tempting to speculate that Cd151 deletion could affect tumor development indirectly through the microenvironment, by modifying the phenotype of the myoepithelial cells. However CD151 is also expressed, to a lesser extent, at the basolateral membrane of the luminal epithelium. It would be interesting to evaluate separately the specific effect of Cd151 deletion in the stroma (tumor vasculature, immune cells, myoepithelial cells) and the luminal epithelium/tumor cells respectively, using a conditional knock-out model. In addition, one could study the tumor cell autonomous versus microenvironment effect by performing orthotopic tumor grafts.

A recent study [19] investigated the impact of Cd151 deletion on tumor onset, growth and metastasis of another well characterized mouse mammary tumor model, the MMTV/Neu model (overexpressing multiple copies of wild-type Neu, the rat homolog of ErbB2). In their study, Deng and colleagues observed a significant delay in tumor onset as well as a decreased number of metastases per animal in the Cd151−/− and Cd151+/− groups compared with Cd151+/+ and they also suggest that the effects of CD151 in the MMTV/Neu model are largely mediated through α6β4 integrin. Together our data shows that Cd151 deletion significantly impairs tumor occurrence and growth. On assessment of lung metastasis, we obtained different results from Deng and colleagues. The median incidence, number and size of lung metastases did not vary with the Cd151 genotype in our study, and the higher metastatic burden in a proportion of wild-type mice was associated with increased primary tumors. These results suggest that ablation of Cd151 does not directly affect metastasis in the PyMT model. Future studies using experimental metastasis models will be required to elucidate the contradictory effects on metastasis in the MMTV/Neu and MMTV/PyMT models.

In addition, two other studies have assessed the role of CD151 on de novo tumorigenesis in mouse cancer models other than breast. Firstly, similarly to our results in the PyMT breast cancer model, Takeda and colleagues have demonstrated that CD151 promotes tumor incidence and multiplicity in a skin carcinogenesis model [14]. Secondly, recent work in our laboratory has shown that deletion of Cd151 reduces spontaneous metastasis of prostate tumors in the TRAMP model [29]. Altogether, the literature and the data we report here identify CD151 as an enhancer of de novo tumorigenesis and/or spontaneous metastasis across a broad range of cancer types.

Interestingly, the functional role of CD151 in tumorigenesis and metastasis has been mainly linked to its association with the laminin receptors in the literature. These adhesion receptors include mostly α3β1, α6β1 and α6β4 integrins in the mammary epithelium. Laminin binding integrins have a well-documented role in malignant cell processes regulating crucial functions such as cell proliferation and invasion. β1-integrins represent the most predominantly expressed integrins in the mammary epithelium and their direct involvement in mammary tumorigenesis has been extensively demonstrated using mouse models of breast cancer. For example, it has been shown that β1-integrin is absolutely required for PyMT mammary tumor initiation and progression [4,30]. Similarly, several studies have demonstrated that ablation of crucial signaling molecules downstream of β1-integrin such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK) also dramatically decreased cancer cell proliferation [31-33]. In contrast to the total block in PyMT induced tumorigenesis, mammary epithelial deletion of β1 integrin in an MMTV/Neu (activated ErbB2) mouse model did not totally prevent tumor development. Although it significantly delayed tumor onset, all of the mice developed tumors that were histologically identical to control mice [34]. The major effect of β1 deletion in the context of activated ErbB2 mammary tumorigenesis was the decrease in incidence of lung metastasis as well as decreased metastatic burden. There is to our knowledge no published report on the role of β4-integrin in the MMTV/PyMT model but it has been shown however that β4-integrin collaborates with ErbB2 to promote mammary tumorigenesis [3,16] in the MMTV/Neu mouse model.

Conclusions

In summary, the results of this study show that CD151 enhances mammary tumor initiation and progression in the MMTV/PyMT mouse model but no direct effect on metastasis was demonstrated. The effects of Cd151 deletion in the MMTV/PyMT model are likely to be mediated by a combination of both β1- and β4-integrins but this remains to be tested. In conclusion, our findings strongly support the relevance of CD151 as a potential therapeutic target to delay breast cancer progression.

Abbreviations

IHC: Immunohistochemistry; NBF: Neutral buffered formalin; PyMT: Polyoma middle T antigen; MMTV: Mouse mammary tumor virus.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SR and LKA conceived and designed the project. MJN participated in the analysis of mammary gland development and differentiation. J.W. participated in the tumor and metastasis data analysis. WJM provided the MMTV/PyMT mouse model and participated in the study design. BTC performed some of the immunohistochemical data analysis. SR and RGK carried out the monitoring of the mice and the tissue collections. SR analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Diagram representing the breeding protocol used to generate the F1 (FVBxB6) PyMT Cd151+/+ and Cd151−/− experimental animals.

Effect of the genetic background on MMTV/PyMT tumor onset. The appearance of mammary tumors in wild-type pure FVB or F1 FVB:B6 mice was monitored by bi-weekly palpation and is represented on a Kaplan-Meier survival curve. T50 indicates the median time to development of a palpable mammary tumor for each group of mice. The difference in T50 between FVB (42 d) and F1 FVB:B6 (62.5 d) was statistically significant (P=0.0001).

Contributor Information

Séverine Roselli, Email: severine.roselli@newcastle.edu.au.

Richard GS Kahl, Email: Richard.kahl@newcastle.edu.au.

Ben T Copeland, Email: bcopela6@jhmi.edu.

Matthew J Naylor, Email: matthew.naylor@sydney.edu.au.

Judith Weidenhofer, Email: Judith.weidenhofer@newcastle.edu.au.

William J Muller, Email: william.muller@mcgill.ca.

Leonie K Ashman, Email: leonie.ashman@newcastle.edu.au.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Celeste Harrison and Matthew Bowman for technical assistance. This work was supported by an early career Fellowship from the Cancer Institute NSW (06/ECF/1/22) and a Gladys M. Brawn Memorial post-doctoral Fellowship to S.R. L.K.A was supported by a Principal Research Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

References

- Sterk LM, Geuijen CA, van den Berg JG, Claessen N, Weening JJ, Sonnenberg A. Association of the tetraspanin CD151 with the laminin-binding integrins alpha3beta1, alpha6beta1, alpha6beta4 and alpha7beta1 in cells in culture and in vivo. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 6):1161–1173. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.6.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahlou H, Muller WJ. Beta1-integrins signaling and mammary tumor progression in transgenic mouse models: implications for human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(6):229. doi: 10.1186/bcr2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Pylayeva Y, Pepe A, Yoshioka T, Muller WJ, Inghirami G, Giancotti FG. Beta 4 integrin amplifies ErbB2 signaling to promote mammary tumorigenesis. Cell. 2006;126(3):489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DE, Kurpios NA, Zuo D, Hassell JA, Blaess S, Mueller U, Muller WJ. Targeted disruption of beta1-integrin in a transgenic mouse model of human breast cancer reveals an essential role in mammary tumor induction. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(2):159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadej R, Romanska H, Baldwin G, Gkirtzimanaki K, Novitskaya V, Filer AD, Krcova Z, Kusinska R, Ehrmann J, Buckley CD, Kordek R, Potemski P, Eliopoulos AG, Lalani e-N, Berditchevski F. CD151 regulates tumorigenesis by modulating the communication between tumor cells and endothelium. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7(6):787–798. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon MJ, Park S, Choi JY, Oh E, Kim YJ, Park YH, Cho EY, Kwon MJ, Nam SJ, Im YH, Shin YK, Choi YL. Clinical significance of CD151 overexpression in subtypes of invasive breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(5):923–930. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang J, Lijovic M, Ashman LK, Kan K, Frauman AG. CD151 protein expression predicts the clinical outcome of low-grade primary prostate cancer better than histologic grading: a new prognostic indicator? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(11 Pt 1):1717–1721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuhara T, Hasegawa H, Hattori N, Ishida H, Taki T, Tachibana S, Sasaki S, Miyake M. Clinical significance of CD151 gene expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(12):4109–4114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Lee K, Chae JY, Moon KC. CD151 expression can predict cancer progression in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Histopathology. 2011;58(2):191–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss MA, Gordon N, Maloney S, Ganesan R, Ludeman L, McCarthy K, Gornall R, Schaller G, Wei W, Berditchevski F, Sundar S. Tetraspanin CD151 is a novel prognostic marker in poor outcome endometrial cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(10):1611–1618. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XH, Richardson AL, Torres-Arzayus MI, Zhou P, Sharma C, Kazarov AR, Andzelm MM, Strominger JL, Brown M, Hemler ME. CD151 accelerates breast cancer by regulating alpha 6 integrin function, signaling, and molecular organization. Cancer Res. 2008;68(9):3204–3213. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda Y, Kazarov AR, Butterfield CE, Hopkins BD, Benjamin LE, Kaipainen A, Hemler ME. Deletion of tetraspanin Cd151 results in decreased pathologic angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Blood. 2007;109(4):1524–1532. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zijlstra A, Lewis J, Degryse B, Stuhlmann H, Quigley JP. The inhibition of tumor cell intravasation and subsequent metastasis via regulation of in vivo tumor cell motility by the tetraspanin CD151. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(3):221–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda Y, Li Q, Kazarov AR, Epardaud M, Elpek K, Turley SJ, Hemler ME. Diminished metastasis in tetraspanin CD151-knockout mice. Blood. 2011;118(2):464–472. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novitskaya V, Romanska H, Dawoud M, Jones JL, Berditchevski F. Tetraspanin CD151 regulates growth of mammary epithelial cells in three-dimensional extracellular matrix: implication for mammary ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer Res. 2010;70(11):4698–4708. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy CT, Cardiff RD, Muller WJ. Induction of mammary tumors by expression of polyomavirus middle T oncogene: a transgenic mouse model for metastatic disease. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12(3):954–961. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EY, Jones JG, Li P, Zhu L, Whitney KD, Muller WJ, Pollard JW. Progression to malignancy in the polyoma middle T oncoprotein mouse breast cancer model provides a reliable model for human diseases. Am J Pathol. 2003;163(5):2113–2126. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63568-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte R, Muller WJ. Signal transduction in transgenic mouse models of human breast cancer–implications for human breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2008;13(3):323–335. doi: 10.1007/s10911-008-9087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Li Q, Hoff J, Novak M, Yang H, Jin H, Erfani SF, Sharma C, Zhou P, Rabinovitz I, Sonnenberg A, Yi Y, Zhou P, Stipp CS, Kaetzel DM, Hemler ME, Yang XH. Integrin-associated CD151 drives ErbB2-evoked mammary tumor onset and metastasis. Neoplasia. 2012;14(8):678–689. doi: 10.1593/neo.12922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MD, Geary SM, Fitter S, Moseley GW, Lau LM, Sheng KC, Apostolopoulos V, Stanley EG, Jackson DE, Ashman LK. Characterization of mice lacking the tetraspanin superfamily member CD151. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(13):5978–5988. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5978-5988.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baleato RM, Guthrie PL, Gubler MC, Ashman LK, Roselli S. Deletion of CD151 results in a strain-dependent glomerular disease due to severe alterations of the glomerular basement membrane. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(4):927–937. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor MJ, Oakes SR, Gardiner-Garden M, Harris J, Blazek K, Ho TW, Li FC, Wynick D, Walker AM, Ormandy CJ. Transcriptional changes underlying the secretory activation phase of mammary gland development. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(7):1868–1883. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuominen VJ, Ruotoistenmaki S, Viitanen A, Jumppanen M, Isola J. ImmunoRatio: a publicly available web application for quantitative image analysis of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and Ki-67. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(4):R56. doi: 10.1186/bcr2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie SA, Maglione JE, Manner CK, Young D, Cardiff RD, MacLeod CL, Ellies LG. Effects of FVB/NJ and C57Bl/6 J strain backgrounds on mammary tumor phenotype in inducible nitric oxide synthase deficient mice. Transgenic Res. 2007;16(2):193–201. doi: 10.1007/s11248-006-9056-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellies LG, Fishman M, Hardison J, Kleeman J, Maglione JE, Manner CK, Cardiff RD, MacLeod CL. Mammary tumor latency is increased in mice lacking the inducible nitric oxide synthase. Int J Canc Suppl J Int Canc Suppl. 2003;106(1):1–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglione JE, Moghanaki D, Young LJ, Manner CK, Ellies LG, Joseph SO, Nicholson B, Cardiff RD, MacLeod CL. Transgenic Polyoma middle-T mice model premalignant mammary disease. Cancer Res. 2001;61(22):8298–8305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak K, Hu M. Do myoepithelial cells hold the key for breast tumor progression? J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2005;10(3):231–247. doi: 10.1007/s10911-005-9584-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursini-Siegel J, Hardy WR, Zuo D, Lam SH, Sanguin-Gendreau V, Cardiff RD, Pawson T, Muller WJ. ShcA signalling is essential for tumour progression in mouse models of human breast cancer. EMBO J. 2008;27(6):910–920. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland BT, Bowman MJ, Ashman LK. Genetic ablation of the tetraspanin CD151 reduces spontaneous metastatic spread of prostate cancer in the TRAMP model. Mol Cancer Res. 2013;11(1):95–105. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontier SM, Muller WJ. Integrins in breast cancer dormancy. APMIS. 2008;116(7–8):677–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahlou H, Sanguin-Gendreau V, Zuo D, Cardiff RD, McLean GW, Frame MC, Muller WJ. Mammary epithelial-specific disruption of the focal adhesion kinase blocks mammary tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(51):20302–20307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710091104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzano PP, Inman DR, Eliceiri KW, Beggs HE, Keely PJ. Mammary epithelial-specific disruption of focal adhesion kinase retards tumor formation and metastasis in a transgenic mouse model of human breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(5):1551–1565. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pylayeva Y, Gillen KM, Gerald W, Beggs HE, Reichardt LF, Giancotti FG. Ras- and PI3K-dependent breast tumorigenesis in mice and humans requires focal adhesion kinase signaling. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(2):252–266. doi: 10.1172/JCI37160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huck L, Pontier SM, Zuo DM, Muller WJ. Beta1-integrin is dispensable for the induction of ErbB2 mammary tumors but plays a critical role in the metastatic phase of tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(35):15559–15564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003034107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Diagram representing the breeding protocol used to generate the F1 (FVBxB6) PyMT Cd151+/+ and Cd151−/− experimental animals.

Effect of the genetic background on MMTV/PyMT tumor onset. The appearance of mammary tumors in wild-type pure FVB or F1 FVB:B6 mice was monitored by bi-weekly palpation and is represented on a Kaplan-Meier survival curve. T50 indicates the median time to development of a palpable mammary tumor for each group of mice. The difference in T50 between FVB (42 d) and F1 FVB:B6 (62.5 d) was statistically significant (P=0.0001).