Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate whether flexibility and gender influence students' posture.

Method:

Evaluation of 60 female and male students, aged 5 to 14 years, divided into two groups: normal flexibility (n=21) and reduced flexibility (n=39). Flexibility and posture were assessed by photogrammetry and by the elevation of the lower limbs in extension, considering the leg angle and the postural evaluation. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were used for data analysis. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to assess the joint influence of flexibility and gender on the posture-dependent variables. After verifying an interactive effect between the variables of gender and flexibility, multiple comparisons using the t test were applied.

Results:

Flexibility influenced the symmetry angle of the knee (p<0.05) and anteroposterior body tilt (p<0.05). Gender did not influence postural angles (p>0.05). There was an interactive effect between the variables of gender and flexibility on the knee symmetry angle (p<0.02). Male students with reduced flexibility had greater asymmetry of the knee when compared to the other subgroups.

Conclusion:

Posture was influenced by an isolated effect of the variable of flexibility and by an interactive effect between gender and flexibility.

Keywords: Range of articular motion, Sex, Posture, Child, Adolescent

Introduction

Human posture is a result of the association between gravity and the body's limbs1 and may undergo changes over time. Alterations commonly begin during the school age, as bodily growth and development occur in that period.2

Age, gender, school backpack weight, anthropometric parameters,3 position at the computer,4 time spent in the sitting position,5 decreased flexibility,6 and less active life style,7 - 9 are some of the factors that generate discomfort, musculoskeletal changes, and influence posture. It is known that adolescents may have scoliosis, body asymmetries, spinal misalignment,10 and pains, which eventually have long-term consequences,11 clinically impairing health and influencing the quality of adult life.

The prevention of musculoskeletal injuries and improvement in muscle movement and performance depend on body flexibility.12 Flexibility is defined as the passive mobility of the body part, whose restriction lies in its own structure,13 which is closely associated to muscle extensibility, range of motion, and plasticity of ligaments and tendons.6 When there is limitation of the latter, the body undergoes a number of counterbalances, in order to establish an adaptive response to a set of disharmonies,14 which may influence the adopted posture.

In addition to flexibility,12 gender can also have an effect on posture, especially on spinal abnormalities, such as cervical lordosis and thoracic kyphosis in boys,15 and lumbar hyperlordosis in girls.16 The literature is scarce regarding the influence of gender on postural changes in the lower limbs. Most of the studies that assess posture evaluate angles that indicate rotation, valgus or varus knees, and positioning of the pelvis.17 - 19

However, the analysis of body symmetry is considered important, since it provides clinical subsidies for flexibility and postural changes to be developed considering the patient as a whole. Clinically, medical assistance is only sought when alterations in children and adolescents are already visible. Therefore, it is necessary to perform postural screening in primary health care to identify these alterations, in order to make timely interventions aimed to minimize and correct inappropriate behaviors.10

When considering the importance of evaluating the posture in children and adolescents and identifying factors that cause postural changes, the authors formulated the hypothesis that flexibility and gender may influence posture. Thus, this study aimed to verify whether flexibility and gender influence the posture of school children and adolescents.

Method

This was a cross-sectional study of a convenience sample, conducted with 60 school children and adolescents in the city of Florianópolis, state of Santa Catarina, Brazil. To characterize the sample, medical history files containing data on the child, such as age, anthropometric measures (body mass and height), and questions that addressed the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study were used. Inclusion criteria were school children and adolescents aged 5 to 14 years, of both genders. Students with special needs, those undergoing orthopedic treatment and/or physical therapy, or presence of other pathologies associated with posture or congenital malformation were excluded.

This study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina, protocol No. 165/2011. The students were included only if parents or guardians agreed with study participation and signed the informed consent.

Body mass was measured using a digital Filizola scale (Filizola, SP, Brazil) with 100 g precision, whereas height was measured with a Sanny stadiometer (Sanny - American Medical do Brasil, SP, Brazil), with 1 mm precision. Photogrammetry was performed using a Sanyo digital camera model VPC-HD2000 (Sanyo, CA, USA), positioned parallel to the floor on a tripod at a height of 0.85 m and at a distance of 3 m from the assessed individual. To calibrate the image, a plumb line was positioned vertically for reference, which had two reflective markers with a distance of 1 m (for consistency with previous measures) between them. The analysis of posture and flexibility was performed through Sapo software (Software for Postural Assessment, FAPESP, SP, Brazil), developed and validated by Ferreira et al.20 It is highly reliable, and is used by healthcare professionals in clinical assessment and follow-up.21

After the consent form had been signed, the clinical history was obtained. Next, the marking of anatomical landmarks was performed by a trained evaluator. White-colored spherical markers of 1 cm in diameter were attached to the body of the school children and adolescents using doublesided tape, to be used as reference when calculating the evaluated angles. To facilitate the location and attaching of markers and to avoid limiting the range of motion, the students were instructed to wear bathing suits. After that, the assessment procedures were divided into two randomized moments in order to avoid the sequence effect: flexibility and posture.

The test of lower limb elevation in extension, in addition to measuring hamstring flexibility, has clinical validity22 and high inter-rater reliability.23 For the flexibility test, the following anatomical landmarks were used: greater trochanter and lateral malleolus, in both limbs. Then, the test of lower limb elevation in extension was applied, in which the subjects were divided into two groups according to the leg angle: normal flexibility, consisting of subjects that had leg angle ≥65º and reduced flexibility, for those with a leg angle <65º.24

This evaluation was performed in accordance with the study by Graciosa et al.23 The images for flexibility analysis were obtained by elevating the lower limb in extension in the sagittal plane, by measuring the angle of the leg (intersection between the leg segment and the horizontal stretcher).23 , 25 To perform the test, the study subject was placed supine on a stretcher positioned 3 m from the camera, with extended legs and flexed arms, with the hands behind the head. In this position, thigh fixation of the contralateral limb was performed by the examiner, to stabilize and prevent its movement, and then the elevation of the lower limb in extension was performed passively. The image was recorded when the subject reported feeling muscle strain in the posterior region of the assessed leg, before performing hip rotation as compensation. This test was performed bilaterally.

The use of photogrammetry to obtain linear and angular measurements is highly reliable for postural assessment.21 , 26 The anatomical markers used for postural analysis were: spinous process of the seventh cervical vertebra (C7), glabella, tragus, acromion, anterosuperior iliac spine, lateral femoral epicondyle, and lateral malleolus, bilaterally. For postural assessment and photographic record, the individual was asked to remain in the standing position with arms extended along the body and feet positioned comfortably on a sheet of paper measuring 30 x 40 cm, on which the contour of the feet was drawn, for use as a template for the photos. This sheet was placed at a distance of 3 m from the camera on a demarcation on the ground to ensure proper positioning of the subject. Then, postural images were recorded in the frontal and sagittal planes for photogrammetry.

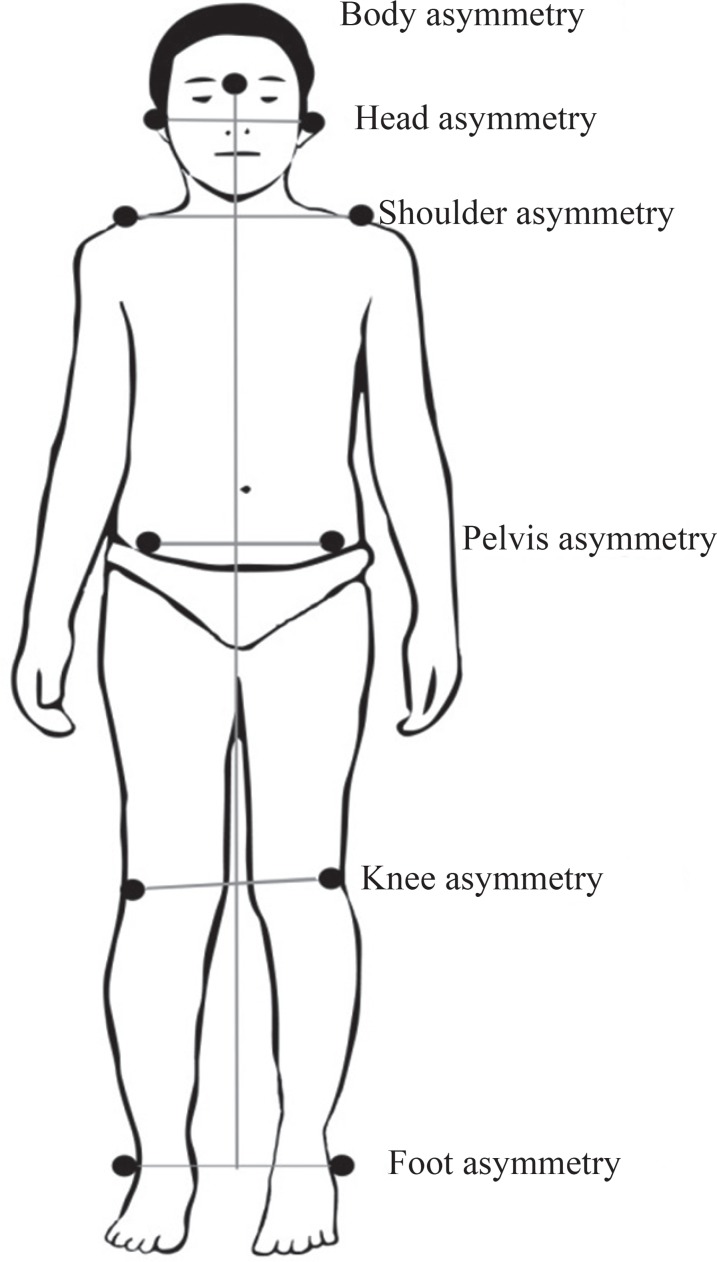

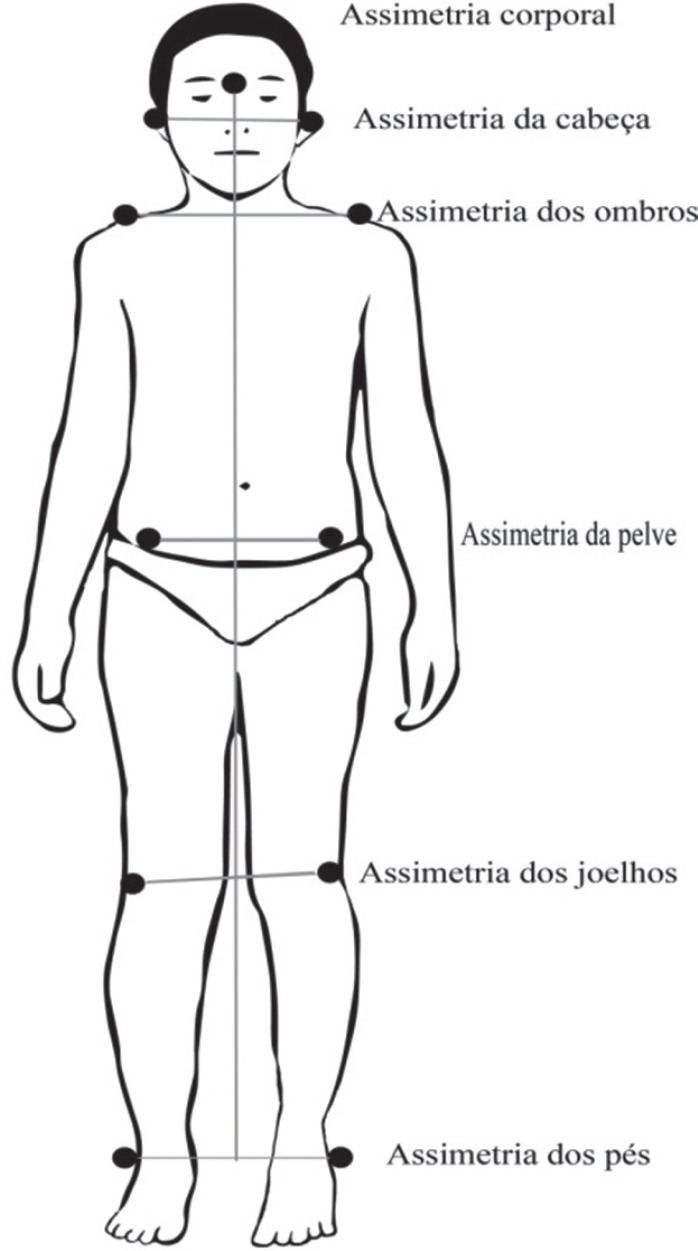

A photographic record was made in each position by a single evaluator. Postural assessment was performed according to the study by Coelho et al. 26 The angles analyzed in the frontal plane were: symmetry of the head, shoulders, pelvis, knees, and malleoli. All were determined by the intersection of the drawn lines, by joining the markers on the right and left side of each anatomical point, and by the straight line horizontally, perpendicular to the plumb line and parallel to the ground. Body symmetry was also analyzed, which was measured by free angle formed by the line passing through the glabella and the midpoint between the malleoli, with a line parallel to the plumb line.27

To ensure the reliability of the postural evaluation, image digitization and angle calculations were performed by two trained evaluators, who analyzed the images independently. The interrater reliability for postural angle measurement was assessed by intraclass correlation coefficient (two-way random ICC). ICC values <0.40 were considered as poor agreement; ICC values between 0.40 and 0.75, as moderate agreement; and ICC>0.75, as high agreement.28 High reliability was obtained in postural angle measurements between the evaluators (all with ICC>0.97, p<0.001) and thus the arithmetic mean of the two raters was considered for the analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Anatomical markings in the frontal plane.

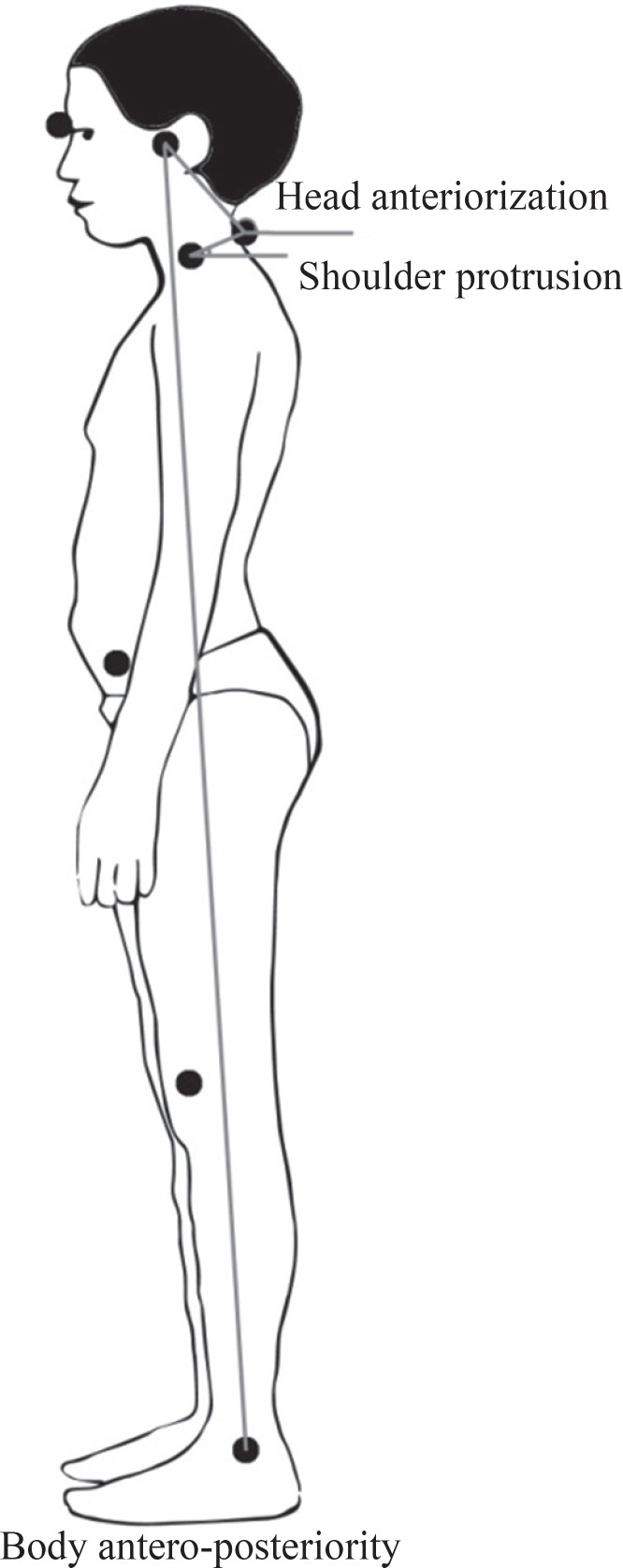

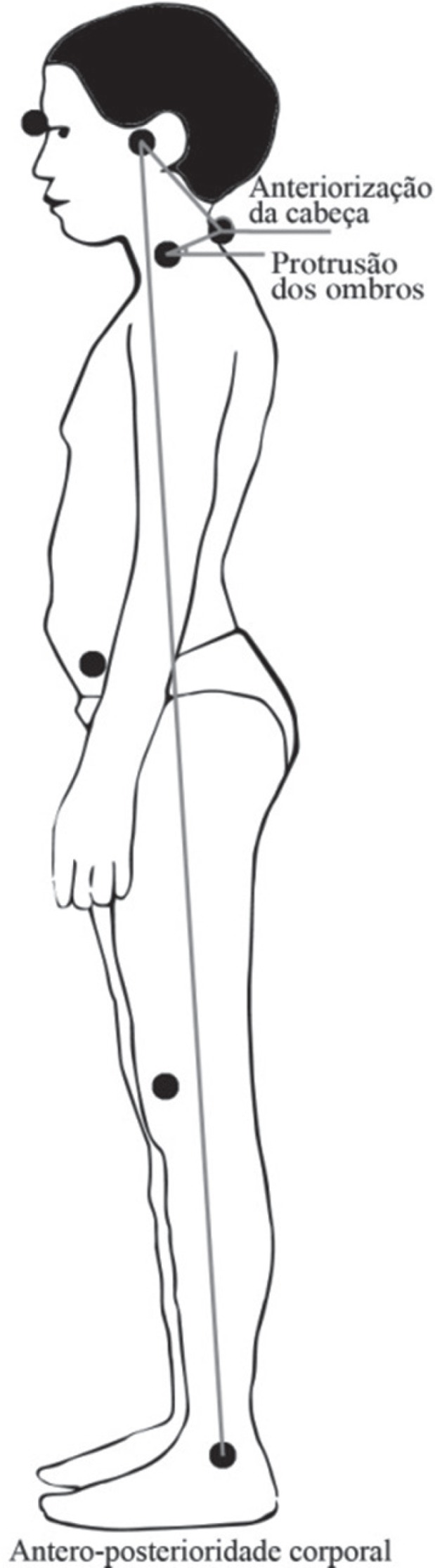

In the sagittal plane, the following were analyzed: head anteriorization (free angle formed by the line passing the tragus marker to the C7 marker and line perpendicular to the plumb line passing through the C7 marker), shoulder protrusion (free angle formed by the line containing the C7 marker to the acromion marker and line perpendicular to the plumb line passing through the acromion marker) and anteroposterior body tilt (free angle formed by the line passing through the tragus marker to the external malleolus marker and line parallel to the plumb line passing through the external malleolus marker27 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Anatomical markings in the sagittal plane.

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were used for data analysis. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to verify the joint effect of the variables of flexibility (normal and reduced) and gender (male and female) on posture-dependent variables (measures of each postural angle). The normality of residuals and homoscedasticity were verified through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Levene's test, respectively. After verifying the interactive effect between the variables of flexibility and gender by ANOVA, multiple comparisons were carried out using the t-test. The program used for statistical analysis was the SPSS, release 20.0 for Windows (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. NY, USA), and a significance level of 5% (0.05) with a two-tailed distribution adopted for all procedures.

Results

The assessed subjects had a mean age of 9.8±2.3 years, height of 1.44±0.15 m, and body mass of 40.2±13.4 kg. Of the students assessed, 25 (42%) were males and 35 (58%) were females; 21 (35%) were classified as having normal flexibility, and 39 (65%) as limited flexibility, with leg angle, respectively, of 76.4±7.0º and 53.1±8.5º.

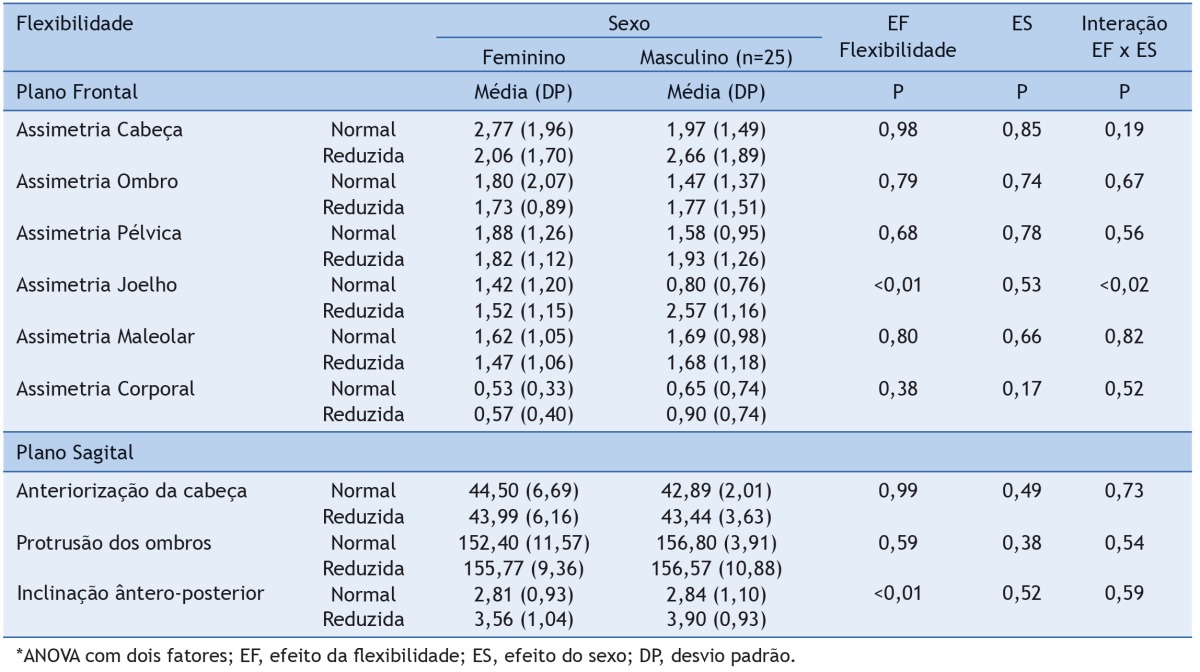

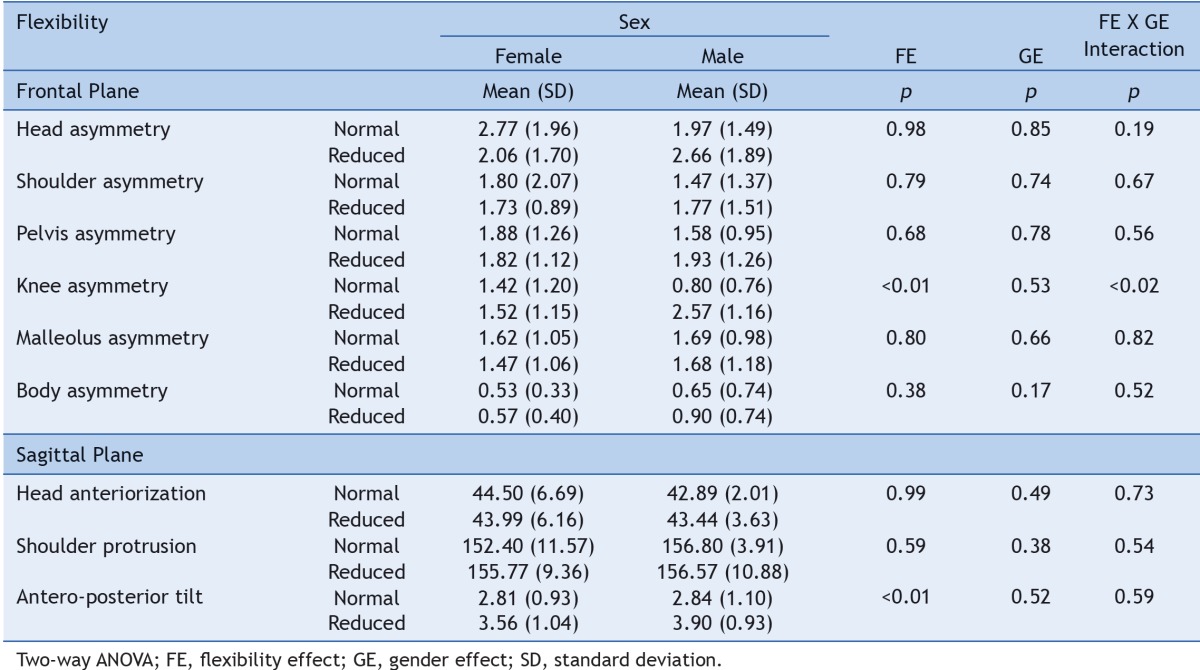

The univariate analysis (Table 1) showed that the variable of flexibility had an effect on the symmetry angle of the knee (p<0.01) and on the anteroposterior body tilt angle (p<0.01). Students with reduced flexibility had greater knee asymmetry and greater anteroposterior body tilt. Gender did not influence postural angles (p>0.05). An interaction was found between the variables of flexibility and gender and symmetry angle of the knee (p<0.02). Male students and subjects with reduced flexibility showed greater asymmetry of the knee when compared to the other subgroups.

Table 1. Scores obtained when evaluating the posture angles of 60 students, divided into female gender with normal (n=15) and reduced (n=20) flexibility and male gender with normal (n=6) and reduced (n=19) flexibility.

The t-test demonstrated that, in males, the asymmetry of the knee in subjects with reduced flexibility was significantly higher than in those with normal flexibility (p<0.01). As for students with limited flexibility, the asymmetry of the knee was significantly higher in males than in females (p<0.01).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated an effect of flexibility on posture only in the asymmetry angles of the knee and anteroposterior body tilt. Individuals with reduced flexibility were the majority and showed greater asymmetry of the knee and greater anteroposterior body tilt.

Reduced flexibility is related to the shortening of the hamstrings.16 , 29 This muscle group originates at the ischial tuberosity and has an important effect on the anteroposterior pelvic tilt.24 A decrease in flexibility in this group can cause postural deviations and affect the function of the lumbar column, as well as of the hip and knee joints.24

The high prevalence of children with reduced flexibility is an object of concern. It was observed that they spend a lot of time in the sitting position in front of computers9 and during school time.30 The time spent in this posture places the posterior muscles of the lower limbs in a shortening position,31 which can generate posterior tilt and misalignment of the pelvis.32

In the present study, although it was not evaluated, the pelvis posture may have influenced the asymmetry of the knees and postural tilt in the sagittal plane observed in the group with reduced flexibility. The interdependence of actions performed by the hamstrings at the hip and knee joints32 suggests that the shortening of the muscl es caused these postural changes. However, the anteroposterior body tilt of the students is also associated with the way they carry the schoolbooks and material. The use of backpacks can cause changes in posture, with an increase in the anterior body tilt,27 in addition to causing other muscle shortenings not controlled in this study.

Regarding gender, it had no significant effect on posture, which did not confirm the initial hypothesis. Although other studies have found gender influence on posture,16 , 33 they evaluated angles that indicated rotations, valgus or varus knees, and positioning of the pelvis.17 , 19 The present study only performed the analysis of symmetry, aiming at overall body posture of school children and adolescents.

The interaction between the variables of gender and flexibility on posture showed that male subjects and those with reduced flexibility had greater asymmetry of the knee when compared to the other subgroups. This result can be explained by cultural differences between boys and girls on their choice of sports practice, as flexibility is influenced by the pattern of physical activity.34 In males, there is prevalence of activities such as soccer, wrestling, and weightlifting.35 In the study by Veiga et al,14 the authors found that intensive and repetitive soccer training results in muscle hypertrophy and decreased levels of flexibility, which can lead to changes in posture.

The reduction in flexibility related to knee asymmetry and greater anteroposterior body tilt determine the greater degree of care necessary for the postural pattern adopted by these children during school years, particularly regarding the time spent in the sitting position, school backpack weight, and physical activity. Furthermore, the high prevalence of reduced flexibility shows the need for early intervention regarding this parameter. A lack of flexibility can impair athletic performance and everyday activities.6

School activities with a global approach, aiming at coordinative motor skills, flexibility, muscular strength, and cardiorespiratory endurance should be applied in the daily routine of schoolchildren and adolescents.23 The evaluation of posture is of utmost importance, especially in individuals of school age, as many postural problems begin at this stage.36 Early correction of posture and increase in the range of motion in childhood and adolescence may result in obtaining more comfortable postures, both in daily movements and in physical activity practice, enabling appropriate postural patterns in adulthood.37

One variable that could affect the results obtained is chronological age. At the stage of 7 to 12 years, changes in posture occur in search of a compatible equilibrium with the new body proportions acquired by growth.21 Thus, the age group assessed was one of the study limitations. It is suggested that future studies use a larger sample size, permitting stratification into subgroups according to age, allowing a more thorough investigation of the influence of gender and flexibility on posture according to each age group. Moreover, as the postural evaluation was performed globally, it was difficult to compare the results with those in the literature, due to the limited number of studies with similar design and sample type.

It can be concluded that in the present study, posture suffered from the isolated effect of the variable of flexibility and the interactive effect between gender and flexibility. Students with reduced flexibility showed knee asymmetry and increased anteroposterior body tilt.

Acknowledgements

To the Programa de iniciação Científica da Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina (PROBiC-UDESC) and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), for the study grants.

Footnotes

Study conducted at Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, SC, Brazil.

Referências

- 1.Gangnet N, Pomero V, Dumas R, Skalli W, Vital JM. Variability of the spine and pelvis location with respect to the gravity line: a three-dimensional stereoradiographic study using a force platform. Surg Radiol Anat. 2003;25:424–433. doi: 10.1007/s00276-003-0154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penha PJ, João SM. Muscle flexibility assessment among boys and girls aged 7 and 8 years old. Fisioter e Pesq. 2008;15:387–391. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azuan M, Zailina H, Shamsul BM, Asyiqin MA, Azhar MN, Aizat IS. Neck, upper back and lower back pain and associated risk factors among primary school children. J Appl Sci. 2010;10:431–435. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs K, Baker NA. The association between children's computer use and musculoskeletal discomfort. Work. 2002;18:221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy S, Buckle P, Stubbs D. Classroom posture and selfreported back and neck pain in schoolchildren. Appl Ergon. 2004;35:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almeida TT, Jabur MN. Mitos e verdades sobre flexibilidade: reflexões sobre o treinamento de flexibilidade na saúde dos seres humanos. Motri. 2007;3:337–344. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva LR, Rodacki AL, Brandalize M, Lopes MF, Bento PC, Leite N. Postural changes in obese and non-obese children and adolescents. Rev Bras Cineant Desemp Hum. 2011;13:448–454. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nunes MM, Figueiroa JN, Alves JG. Overweight, physical activity and foods habits in adolescents from different economic levels, Campina Grande (PB) Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2007;53:130–134. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302007000200017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Really JJ. Physical activity, sedentary behaviour and energy balance in the preschool child: opportunities for early obesity prevention. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67:317–325. doi: 10.1017/S0029665108008604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nery LS, Halpern R, Nery PC, Nehme KP, Tetelbom AS. Prevalence of scoliosis among school students in a town in southern Brazil. Sao Paulo Med J. 2010;128:69–73. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802010000200005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeffries LJ, Milanese SF, Grimmer-Somers KA. Epidemiology of adolescent spinal pain: a systematic review of the research literature. Spine. 2007;32:2630–2637. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318158d70b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikkelson LO, Nupponen H, Kaprio J, Kautiainen H, Mikkelson M, Kujala UM. Adolescent flexibility, endurance strength, and physical activity as predictors of adult tension neck, low-back pain, and knee injury: a 25-year follow up study. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:107–113. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.017350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laessoe U, Voigt M. Modification of stretch tolerance in a stooping position. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2004;14:239–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2003.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veiga PH, Daher CR, Morais MF. Postural alterations and flexibility of the posterior chain in soccer´s injuries. Rev Bras Cienc Esporte. 2011;33:235–248. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penha PJ, Casarotto RA, Sacco IC, Marques AP, João SM. Qualitative postural analysis among boys and girls of seven to ten years of age. Rev Bras Fisioter. 2008;12:386–391. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemos AT, Santos FR, Gaya AC. Lumbar hyperlordosis in children and adolescents at a privative school in southern Brazil: occurrence and associated factors. Cad Saude Publica. 2012;28:781–788. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2012000400017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santos MM, Silva MP, Sanada LS, Alves CR. Photogrammetric postural analysis on healthy seven to ten-year-old children: interrater reliability. Rev Bras Fisioter. 2009;13:350–355. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinto AL, Holanda PM, Radu AS, Villares SM, Lima FR. Musculoskeletal findings in obese children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42:341–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinelli AR, Purga MO, Mantovani AM, Camargo MR, Rosell AA, Fregonesi CE, et al. Analysis of lower limb alignment in overweight children. Rev Bras Cineant Des Hum. 2011;13:124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferreira EA, Duarte M, Maldonado EP, Burke TN, Marques AP. Postural assessment software (PAS/SAPO): validation and reliabiliy. Clinics. 2010;65:675–681. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322010000700005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iunes DH, Castro FA, Salgado HS, Moura IC, Oliveira AS, Bevilaqua-Grossi D. Confiabilidade intra e interexaminadores e repetibilidade da avaliação postural pela fotogrametria. Rev Bras Fisioter. 2005;9:327–334. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gajdosik RL. Passive extensibility of skeletal muscle: review of the literature with clinical implications. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2001;16:87–101. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(00)00061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coelho JJ, Graciosa D, da Costa LM, Medeiros DL, Martinello M, Ries LG. Effect of sedentary lifestyle, nutritional status and sex on the flexibility of students. Rev Bras Crescimento Desenvolv Hum. 2013;23:144–150. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carregaro RL, Silva LC, Gil Coury HJ. Comparison between two clinical tests for evaluating the flexibility of the posterior muscles of the thigh. Rev Bras Fisioter. 2007;11:139–145. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pagnussat AS, Paganotto KM. tudy of lumbar curvature in the structural development phase. Fisioter Mov. 2008;21:39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coelho JJ, Graciosa MD, Medeiros DL, da Costa LM, Martinello M, Ries LG. Influence of nutritional status and physical activity on the posture of children and adolescents. Fisioter Pesq. 2013;20:136–142. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ries LG, Martinello M, Medeiros M, Cardoso M. Peso da mochila escolar, sintomas osteomusculares e alinhamento postural de escolares do ensino fundamental. Ter Man. 2011;9:190–196. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Estatistical methods for rates and proportions. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 29.López-Miñarro PA, Alacid F, Muyor JM. Influence of hamstring muscle extensibility on spinal curvatures in young athletes. J Hum Kinet. 2011;29:15–23. doi: 10.2478/v10078-011-0035-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wouters F, Alves AC, Villaverde AG, Albertini R. Relação entre retroversão pélvica e dores musculoesqueléticas com tempo gasto por escolares na postura sentada. Ter Man. 2011;9:551–557. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sacco IC, Alibert S, Queiroz BW, Pripas D, Kieling I, Kimura AA. Reliability of photogrammetry in relation to goniometry for postural lower limb assessment. Rev Bras Fisioter. 2007;11:411–417. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polachini LO, Fuzasaki L, Tamaso M, Tellini GG, Masieiro D. Estudo comparativo entre três métodos de avaliação do encurtamento de musculatura posterior da coxa. Rev Bras Fisioter. 2005;9:187–193. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen AD, Shultz SJ. Sex differences in clinical measures of lower extremity alignment. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37:389–398. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2007.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melo FA, Oliveira MF, Almeida MB. Nível de atividade física não identifica o nível de flexibilidade de adolescentes. Rev Bras Ativ Fis Saude. 2009;14:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salles-Costa R, Heilborn ML, Werneck GL, Faerstein E, Lopes CS. Gender and leisure-time physical activity. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19:325–333. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2003000800014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bunnell WP. Selective screening for scoliosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005:40–45. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000163242.92733.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martelli RC, Traebert J. Descriptive study of backbone postural changes in 10 to 16 year-old schoolchildren. Tangará-SC, Brazil, 2004. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2006;9:87–93. [Google Scholar]