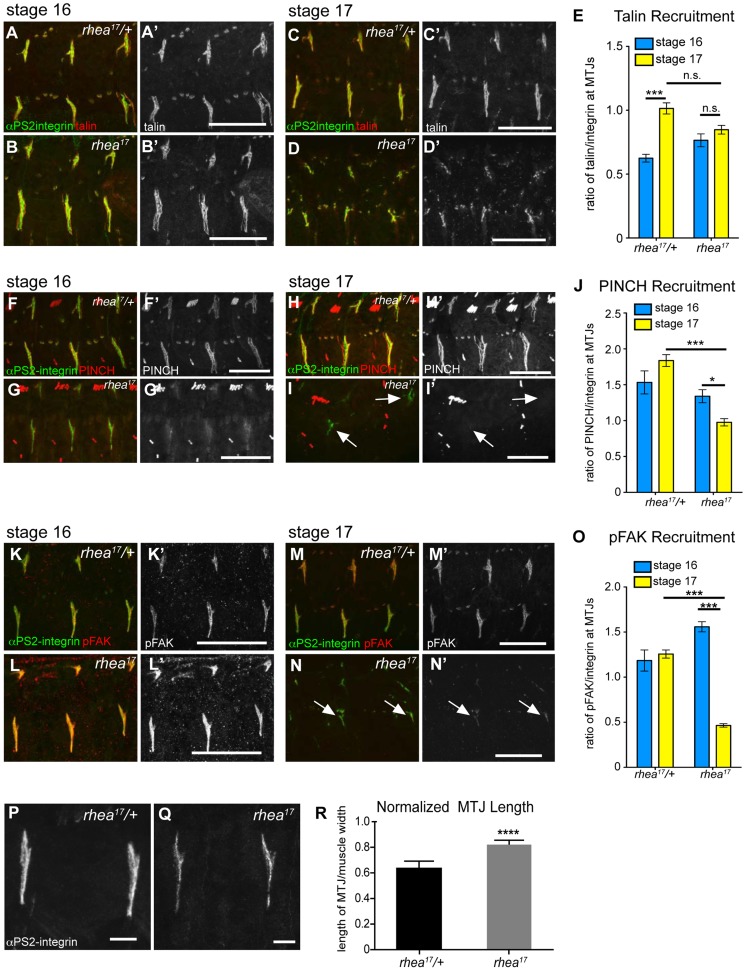

Figure 5. rhea17 disrupts adhesion complex reinforcement and adhesion consolidation.

WT and rhea17 embryonic muscles stained for talin (red in a–d; grey in a′–d′) and integrin (green in a–d) at stage 16 (a–b) and stage 17 (c–d). (e) The recruitment of talin to adhesions (normalized to integrin levels; see materials and methods) was comparable between WT and rhea17 in stage 16 embryos. However, although talin was maintained at sites of adhesion, its recruitment was not reinforced in rhea17 embryos in stage 17 embryos (e). (f–j). WT and rhea17 embryos stained for integrin (green in f–i) and PINCH (red in f–i, grey in f′–i′) at stage 16 (f–g) and stage 17 (h–i). PINCH recruitment was not reinforced in stage 17 rhea17 embryos as determined by measuring the ratio of anti-PINCH fluorescence intensity relative to integrin intensity at MTJs. (j; see Materials and Methods). (k–o) WT and rhea17 embryos stained for integrin (green in k–n) and pFAK (red in k–n; grey in k′–n′). pFAK recruitment was not reinforced in stage 17 rhea17 embryos as determined by measuring the ratio of anti-pFAK fluorescence intensity relative to integrin intensity at MTJs (o; see Materials and Methods). (p–r) MTJ length was measured in control heterozygous (p) and rhea17 mutant (q) embryos (see materials and methods). MTJs were significantly longer in rhea17 mutants compared to control embryos (****p<0.0001). Scale bars: a–n = 50 µm; p–q = 10 µm.