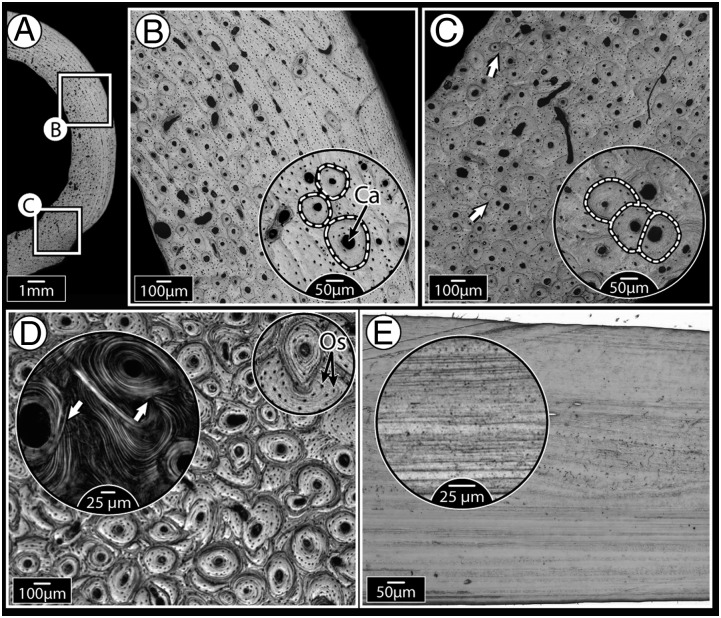

Fig. 1.

Mammalian bone ultrastructure, showing morphological evidence for remodeling, compared with relatively “featureless” fish bone. (A) Cross-section of dog femoral midshaft with localized areas showing primary and remodeled bone (secondary osteons). (B) Higher magnification of the upper boxed region in A, showing isolated, nonoverlapping osteons (borders indicated by dashed lines) present in otherwise lamellar (layered) primary bone tissue. Every osteon is organized around a central Haversian canal (Ca); smaller black dots are osteocyte lacunae. (C) Higher magnification of the lower boxed region in A, showing much higher osteonal density, with many overlapping osteons (secondary osteons, shown by arrows, and in more detail in the inset image), indications of tissue remodeling. (D) Horse third metatarsal bone showing heavy remodeling, evidenced by extensive osteonal overlap. Inset polarized microscopy image illustrates how osteonal lamellae are “interrupted” by lamellae of new osteons (white arrows). The smaller Inset image highlights the high concentration of osteocyte lacunae (Os), visible as small black dots throughout the tissue. (E) Tilapia opercular bone which, like most fish bone examined to date, has a simple layered ultrastructure, even at higher magnification (Inset). This species is anosteocytic (i.e., lacks osteocytes entirely); in contrast, the mammalian tissues in A–D all have numerous osteocytes.