Abstract

Indolotryptoline natural products represent a small family of structurally unique chromopyrrolic acid-derived antiproliferative agents. Like many prospective anticancer agents before them, the exploration of their potential clinical utility has been hindered by the limited information known about their mechanism of action. To study the mode of action of two closely related indolotryptolines (BE-54017, cladoniamide A), we selected for drug resistant mutants using a multidrug resistance-suppressed (MDR-sup) Schizosaccharomyces pombe strain. As fission yeast maintains many of the basic cancer-relevant cellular processes present in human cells, it represents an appealing model to use in determining the potential molecular target of antiproliferative natural products through resistant mutant screening. Full genome sequencing of resistant mutants identified mutations in the c and c′ subunits of the proteolipid substructure of the vacuolar H+-ATPase complex (V-ATPase). This collection of resistance-conferring mutations maps to a site that is distant from the nucleotide-binding sites of V-ATPase and distinct from sites found to confer resistance to known V-ATPase inhibitors. Acid vacuole staining, cross-resistance studies, and direct c/c′ subunit mutagenesis all suggest that indolotryptolines are likely a structurally novel class of V-ATPase inhibitors. This work demonstrates the general utility of resistant mutant selection using MDR-sup S. pombe as a rapid and potentially systematic approach for studying the modes of action of cytotoxic natural products.

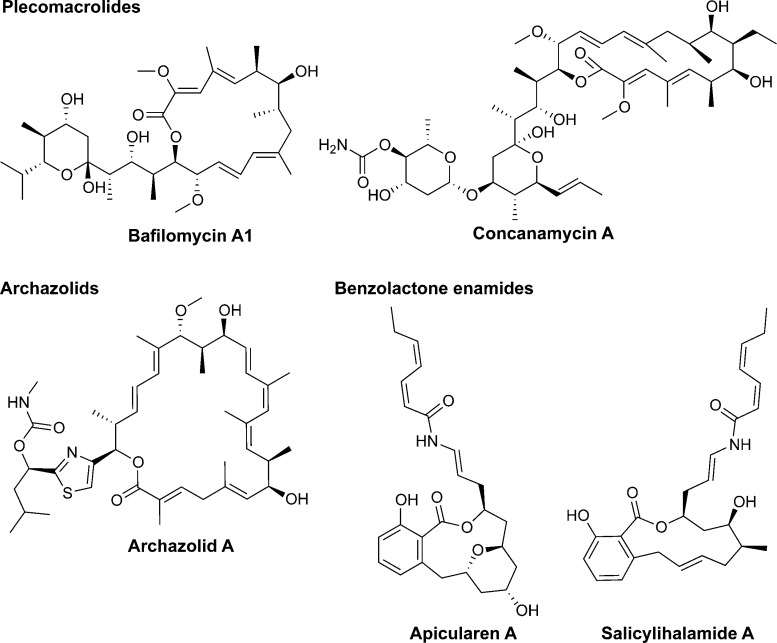

A number of biologically active natural products arise from the biosynthetic coupling and subsequent oxidative rearrangement of two tryptophans (e.g., tryptophan dimers).1 One rare subclass of this general family is the indolotryptolines, which are characterized by the presence of a tricyclic tryptoline fused to an indole in the final structure (Figure 1).2,3 The two reported indolotryptolines, BE-540174 and cladoniamide A,5 both exhibit potent (nanomolar) antiproliferative activity against diverse cancer cell lines in vitro. As this is one of the defining characteristics for natural products that have successfully transitioned into clinically useful cancer chemotherapy drugs,6,7 these compounds have recently attracted an increasing level of interest.3,8−11

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of indolotryptoline (green)- and indolocarbazole (red)-containing natural product cytotoxins.

While biological studies of indolotryptolines are still in their infancy, the biological activities of the more common indolocarbazole-type natural product tryptophan dimers, which differ from indolotryptolines by the presence of a tricyclic carbazole in place of a tryptoline, have been extensively studied (Figure 1).12 More than 100 natural indolocarbazoles have been discovered to date, with many showing potent in vitro cytotoxicity,13 and both natural and synthetic derivatives of the indolocarbazoles, staurosporine and rebeccamycin, have been introduced into clinical trials as cancer therapeutic agents.14 One of the key events in the therapeutic development of indolocarbazole-related metabolites (e.g., Gleevac and others)15 was the determination that although staurosporine and rebeccamycin bind unique molecular targets (e.g., protein kinase and DNA topoisomerase I, respectively), they function through a common binding motif involving their interaction at the nucleotide (i.e., ATP or DNA)-binding site of the target protein.16,17

A recent high-throughput screen for small molecule inhibitors of the vacuolar-type H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) seredipidously found that BE-54017 shows V-ATPase inhibitory activity in a human cell line.18 The V-ATPase is highly conserved across eukaryotes and is responsible for pumping protons across the plasma membranes and acidifying an array of intracellular organelles.19,20 As the V-ATPase is increasingly viewed as a potentially underexplored target for anticancer therapy because of the variety of pH gradients observed in cancer development,21,22 we were interested in using a more systematic genome-wide approach to either genetically corroborate V-ATPase or possibly identify a different entity as the physiologically relevant molecular target of indolotryptolines.

Elucidating the molecular target of a bioactive small molecule in a genome-wide context remains a significant challenge.23,24 This is especially true when studying cytotoxic natural products that might serve as anticancer agents. One approach for determining the mode of action of a small molecule involves the selection and full genome sequencing of mutants that acquire compound resistance.25 Upon identification of resistance-conferring mutations, a compound’s effect on the activity of both the mutant and wild-type gene products can be used to directly validate a proposed mode of action. This powerful approach is commonly employed for target identification of antimicrobial natural products.26,27 However, its application to antitumor natural product mode of action studies has been limited because of the time-consuming, costly, and cumbersome nature of conducting these experiments using human cells.

Yeasts are often used as a eukaryotic model for antineoplastic mode of action studies because of their small genomes, fast growth rates, and genetic tractability.28 While budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) have usually been used in these types of studies, fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) maintain many more of the basic cancer-relevant cellular processes present in human cells (e.g., cell division, DNA replication, and heterochromatin assembly), making fission yeast a potentially much more general model for mode of action studies.29 However, despite the clear biological advantages fission yeast provide, resistant mutant screening has seldom been employed in S. pombe, because of its robust multidrug resistance (MDR) response and therefore lack of sensitivity to many cytotoxins.30 A recent study identified five major contributors to fission yeast’s MDR phenotype (four drug efflux transporters and a transcription factor) and showed that their deletion results in the increased sensitivity of S. pombe to a wide range of chemical toxins.31 This MDR-suppressed (MDR-sup) strain of S. pombe should be particularly well suited for antiproliferative natural product target identification studies because of its broad sensitivity to cytotoxins and its weakened ability to acquire drug resistance through uninformative, nonspecific MDR mechanisms.

Here we have used MDR-sup S. pombe to study the mode of action of the indolotryptoline-containing natural products, BE-54017 and cladoniamide A (Figure 2). Whole-genome sequencing of indolotryptoline resistant MDR-sup S. pombe mutants identified point mutations in the c/c′ proteolipid subunits of the V-ATPase. The reintroduction of these mutations into a clean background showed that they were necessary and sufficient for indolotryptoline resistance. Fluorescent visualization of acidic vacuoles confirms that the indolotryptolines inhibit V-ATPase activity and that the mutations in the proteolipid subunits provide resistance to V-ATPase inhibitory activity by indolotryptolines. Mapping of the observed resistance-conferring mutations onto a model proteolipid structure shows that indolotryptoline-conferring mutations map to a site that is distinct from sites known to confer resistance to previously described V-ATPase inhibitors. As well as providing corroborative genetic evidence of the predicted molecular target of indolotryptoline natural products, this work demonstrates that resistant mutant screening using MDR-sup S. pombe can serve as a simple and generic tool for natural product mode of action studies.

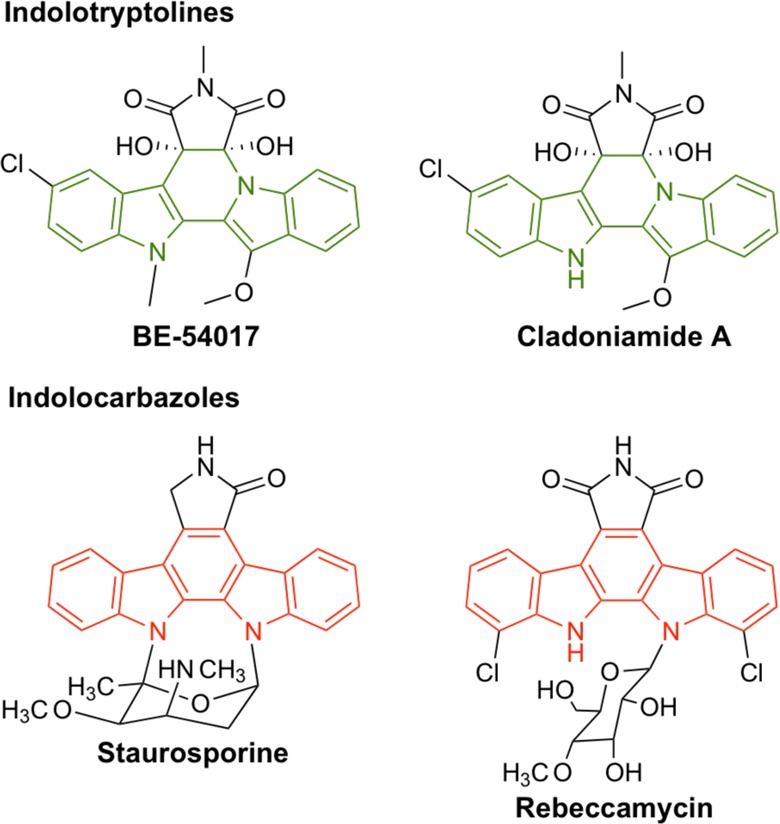

Figure 2.

Four-step schematic for resistance screening using S. pombe. For mutagenesis, the S. pombe strain with its multidrug resistance (MDR) response suppressed (MDR-sup) through five-gene knockouts (KO) is randomly mutagenized with methylnitronitrosoguanidine (NTG). For selection, NTG-mutagenized cells are plated on drug-containing solid media to select for resistant mutants. For backcrossing, drug resistant mutants (orange) are crossed with unmutagenized MDR-sup (white), resulting in the formation of ascus containing four spore progeny with a decrease in the number of mutations. Progeny retaining drug resistance (orange) are maintained. For sequencing, the genome of each backcrossed mutant is sequenced and compared to the unmutagenized parent genome to identify the specific mutation that confers drug resistance.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Strains

The multidrug resistance-suppressed (MDR-sup) S. pombe, SAK84 and SAK690, and the MDR-active S. pombe SAK1, from which MDR-sup S. pombe was derived, were generously provided by T. M. Kapoor (Laboratory of Chemistry and Cell Biology, The Rockefeller University). The genotypes32,33 of these strains are listed in Table S1 of the Supporting Information. The indolotryptoline-based compounds, BE-54017 and cladoniamide A, were isolated from Streptomyces albus harboring the abe gene cluster, as described previously.2 Bafilomycin A1, concanamycin A, and brefeldin A were purchased from a commercial supplier (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

S. pombe Whole-Cell Cytotoxicity Assay

Freshly struck MDR-sup S. pombe SAK84 was inoculated into liquid YE4S medium and grown (30 °C, 300 rpm) to log phase (OD595 = 0.5). The culture was diluted 50-fold and distributed as 100 μL aliquots into a sterile 96-well microtiter plate. BE-54017 or cladoniamide A resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to the first well at an initial concentration of 0.50 μg/mL (1109 nM for BE-54017 and 1144 nM for Cladoniamide A) and serially diluted 2-fold across the plate (final concentrations of 0.50, 0.25, 0.13, 0.063, 0.031, 0.016, 0.0078, 0.0039, 0.0020, 0.0010, 0.00050, and 0.00025 μg/mL). A compound-free DMSO control was similarly diluted across the plate (final DMSO concentration of <1%; no effect was observed on the apparent growth rate of MDR-sup S. pombe). After outgrowth (36 h, 30 °C, 300 rpm), the absorbance (OD595) of each well was measured using a microplate reader (Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer, BioTek). Using GraphPad Prism, the normalized absorbance values were plotted and curve-fitted to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for each indolotryptoline. The same method (using different initial drug concentrations) was used to determine IC50 values for bafilomycin A1, concanamycin A, and brefeldin A against resistant and nonmutant strains.

Selection of Indolotryptoline Resistant S. pombe Mutants

Twenty milliliters of log phase S. pombe SAK84 was pelleted by centrifugation (3000g for 3 min) and resuspended in TM buffer [50 mM Tris, 50 mM maleic acid, 7.5 mM (NH4)2SO4, and 0.4 mM MgSO4 (pH 6.0)] containing 50 μg/mL methylnitronitrosoguanidine (NTG) to randomly mutagenize the genome. After 30 min at 32 °C (250 rpm), the mutagenized cells were pelleted, washed twice with 10 mL of sterile water, resuspended in 20 mL of fresh YE4S, and allowed to recover for 3 h (32 °C and 250 rpm). The culture was adjusted to an OD595 of 0.5, and 150 μL aliquots were spread onto YE4S plates containing different concentrations of the indolotryptolines. After 72 h at 32 °C, resistant clones were picked from plates containing either ∼10 (BE-54017, 69 nM; cladoniamide A, 143 nM) or ∼50 (BE-54017, 35 nM; cladoniamide A, 72 nM) colonies. Each strain was then reassessed for indolotryptoline resistance and cross-resistance to brefeldin A using the whole-cell cytotoxicity assay described above.

Backcrossing of Indolotryptoline Resistant Mutants

Resistant strains were crossed with nonmutant MDR-sup strain SAK690, which differs in genetic background from SAK84 only by having a different mating type (h-). Both resistant and nonmutant S. pombe strains grown on YE4S plates were resuspended in water to produce suspensions with an OD595 of ∼1. These were mixed in equal volumes, and 10 μL aliquots were spotted onto an SPA plate. After 40 h at 25 °C, the mixture was struck onto a YE4S plate. Using a dissecting microscope/micromanipulator (Axioskop 40, Zeiss), zygotic asci (mating products) were isolated from the YE4S plate and incubated (37 °C for 6 h) to permit native digestion of the ascus wall. The four spores from each zygotic ascus were then separated and individually grown on a YE4S plate (30 °C for 5 days). The resulting colonies were tested for resistance to indolotryptolines, and resistant colonies were used in subsequent rounds of backcrossing. For additional rounds of backcrossing, the progeny that retained resistance were crossed, depending on their mating type, with either SAK84 or SAK690.

Whole-Genome Sequencing and Bioinformatics

Backcrossed mutants were grown in YE4S, and genomic DNA was isolated from these cultures using zymolyase treatment followed by phenol/chloroform extraction.34 Genomic DNA from six resistant mutants and two nonmutant strains (SAK84 and SAK690) was sequenced at the Rockefeller University Genomics Resource Center using Illumina HiSeq 2000 technology (50 bp single end, ∼150 million reads in total). Reads from resistant mutants were compared to those of nonmutant samples to identify resistant mutant specific somatic mutations that altered the wild-type amino acid sequence with ≥4× coverage and >50% mutation allele frequency. In brief, the variant detection pipeline consisted of the mapping of Illumina reads to the S. pombe genome29 using BWA, removal of duplicates, indel-based realignment using GATK, base quality score recalibration, mutation calling for a single-nucleotide variant using a GATK Unified Genotyper, and annotation using SnpEff (Sloan Kettering Bioinformatics Core).

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Sequencing of V-ATPase Proteolipid Subunit Genes

A fresh colony of each resistant strain that was not sequenced by HiSeq was resuspended in 0.2% SDS and heated at 95 °C for 10 min. One microliter of this crude cell lysate was used as a template in PCRs designed to amplify the vma3, vma11, and zhf1 genes (Phusion Hot Start Flex DNA polymerase kit, New England Biolabs). Primers are listed in Table S2 of the Supporting Information. The following PCR cycling conditions were used: one cycle of 95 °C for 2 min; 30 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s per kilobase; one cycle for 7 min at 72 °C; and hold at 4 °C. The resulting amplicons were sequenced from both ends using the same set of primers that were used for PCR.

Targeted Mutagenesis of the S. pombe Genome

The vma3 or vma11 specific recombination cassettes containing point mutations of interest were amplified from the appropriate resistant mutant using the same Phusion Hot Start Flex PCR conditions described previously. Primers were designed (Table S2 of the Supporting Information) to generate amplicons with ∼500 bp homology arms flanking each side of the point mutation of interest. The PCR cassette was introduced into SAK84 by lithium acetate-assisted transformation.34 The transformation reaction mixture was spread onto YE4S plates containing defined concentrations of indolotryptoline to select for strains conferring drug resistance. The acquisition of drug resistance and point mutation were confirmed by a whole-cell cytotoxicity assay and PCR sequencing, respectively.

V-ATPase Activity Assay by Acidic Organelle Staining

Log phase S. pombe was added to fresh indolotryptoline-containing media [final concentrations of 0.50 (1109 nM for BE-54017 and 1144 nM for cladoniamide A), 0.25, 0.13, 0.063, 0.031, 0.016, 0.0078, and 0.0039 μg/mL] to give 5 mL cultures with an OD595 of 0.15. These cultures were grown at 30 °C for 1 h, pelleted (2 min at 3000g), and washed with YE4S buffered with 50 mM MOPS (pH 7.6). The cell pellet was then resuspended in buffered YE4S containing 200 μM quinacrine, and staining was allowed to proceed at room temperature for 10 min. After being washed with buffered YE4S, the samples were resuspended in the same medium and transferred to an eight-chamber slide. Cells were imaged at the Rockefeller University Bio-Imagining Resource Center under a fluorescent microscope using a 100× objective lens with DIC optics for Nomarski imaging or with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) filter set for quinacrine visualization (DeltaVision Image Restoration Microscope System with Olympus IX-70 base microscope, Applied Precision). A minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the minimum dose at which the formation of fluorescent puncta was inhibited in >95% of the cells.

Mapping of Resistance-Conferring Residues onto a V-ATPase Structure

The Enterococcus hirae Na+-ATPase proteolipid subunit, NtpK [Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry 2bl2], was imaged using PyMOL. A CLUSTALW alignment of S. pombe V-ATPase proteolipid subunits Vma3 and Vma11 and NtpK was created to map residues between proteins from the two organisms. Residues that confer resistance to indolotryptoline and plecomacrolide compounds were identified in NtpK based on this alignment. Side chains for resistance-conferring residues were converted to those seen in wild-type Vma3 or Vma11 and then represented as colored sticks on the NtpK structure.

Results

Random Mutagenesis and Selection of Indolotryptoline Resistant MDR-sup S. pombe Mutants

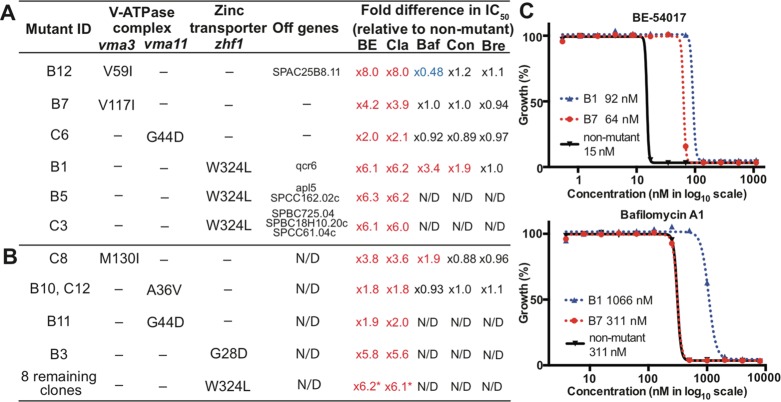

As an initial step in investigating the mode of action of indolotryptolines, methylnitronitrosoguanidine (NTG)-mutagenized MDR-sup S. pombe was plated on medium containing either BE-54017 or cladoniamide A (Figure 2). For both metabolites, concentrations ranging from 2- to 6-fold above the IC50 (BE-54017, 35–70 nM; cladoniamide A, 70–150 nM) were used for resistant mutant selections, which yielded between 1 and 10 resistant colonies per 100000 mutagenized cells. In contrast, the S. pombe strain from which MDR-sup S. pombe was derived (MDR-active S. pombe) is approximately 50 times less sensitive to these natural products (IC50 values of 780 nM for BE-54017 and 1600 nM for cladoniamide A). For each target compound, we picked 12 resistant colonies for further analysis (S. pombe strains B1–B12 for BE-54017 and S. pombe strains C1–12 for cladoniamide A). These 24 mutants were re-examined for indolotryptoline resistance and tested for cross-resistance to the unrelated cytotoxin, brefeldin A (protein transport inhibitor). Strains that failed to show resistance when they were rescreened against indolotryptolines (B2, B9, C1, and C11) and those showing cross-resistance to brefeldin A (C7) were abandoned. All of the remaining strains were found to be resistant to both BE-54017 and cladoniamide A, suggesting a common mode of action and drug-binding site. The IC50 for these resistant mutants ranged from 2- to 8-fold above the IC50 determined for unmutagenized MDR-sup S. pombe (Figure 3 and Figure S1 of the Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

Data from BE-54017 (B#) and cladoniamide A (C#) resistant mutant strains. Compilation of data from either (A) fully sequenced or (B) vma3, vma11, or zhf1 PCR-sequenced resistant mutants. Genes containing mutations, the amino acid change encoded by each mutation, and the fold difference in whole-cell cytotoxicity (IC50) relative to the unmutagenized strain are shown. Abbreviations: BE, BE-54017; Cla, cladoniamide A; Baf, bafilomycin A1; Con, concanamycin A; Bre, brefeldin A; N/D, not determined. The numbers followed by asterisks represent average values. (C) Examples of dose response curves used to determine whole-cell cytotoxicity and fold differences in IC50. Curves for BE-54017 and bafilomycin A1 against mutant B1, mutant B7, or unmutagenized MDR-sup S. pombe are shown. See also Figure S1 and Table S3 of the Supporting Information.

Characterization of Indolotryptoline Resistance-Conferring Mutations by Backcrossing and Sequencing

Random NTG mutagenesis can result in the introduction of multiple mutations into the genome of each strain, complicating the identification of the specific mutations that are relevant to the molecular target. An additional benefit of using fission yeast as a model for the resistance selection approach is that the complexity of the mutagenized genetic background can be significantly simplified through backcrossing with unmutagenized yeast (Figure 2). Backcrossing serves to replace non-drug resistance-associated mutations with wild-type allelles from the unmutagenized strain, thereby preventing irrelevant mutations from complicating downstream genome-wide bioinformatics analyses. Six representative mutant strains showing varying levels of resistance (B1, B5, B7, B12, C3, and C6) were backcrossed four to six times with unmutagenized MDR-sup S. pombe (Figure 3). Consistently, two of the four progeny from each backcross retained drug resistance, suggesting that a single mutation was responsible for the observed resistant phenotype in each strain. The final backcrossed clones were subjected to Illumina whole-genome sequencing, and the resulting reads were mapped onto the unmutagenized MDR-sup genome to identify differences in protein-coding sequences. Upon comparison to the unmutagenized MDR-sup genome, the six backcrossed strains were found to contain between one and four point mutations (Figure 3A). While various one-off mutations (e.g., qcr6 in B1 and apl5 in B5) were observed in this strain collection, every resistant strain had mutations either in the zinc transporter gene, zhf1 (B1, B5, and C3), or in genes encoding the c (vma3 for B7 and B12) or c′ (vma11 for C6) subunits of the vacuolar H+-ATPase complex (V-ATPase), suggesting that zinc transporter and V-ATPase activity were likely linked to the molecular mechanism of indolotryptoline cytotoxicity. In no cases did we detect mutations that might traditionally be associated with a generic MDR-like phenotype, highlighting a key advantage of using the MDR-sup strain.

The zhf1, vma3, and vma11 genes from the 13 resistant strains that were not analyzed by Illumina whole-genome sequencing were amplified via PCR and individually sequenced (Figure 3B). All 13 strains were found to contain a mutation in one of these three genes. Eight strains contain the same zhf1 mutation (W324L) observed previously, making it the most common mutation we detected. Four strains contain new variants of vma3 (C8), vma11 (B10 and C12), and zhf1 (B3), and the remaining strain B11 has the same vma11 mutation that is seen in C6.

Targeted Mutagenesis of V-ATPase and Zinc Transporter Genes

The genetic tractability of yeast allows for a specific mutation of interest to be easily introduced into a clean background to provide a genetic validation of its role in conferring resistance. To confirm the relevance of the vma and zhf mutations to indolotryptoline resistance, each unique vma3/11 point mutation (B7, B10, B12, C6, and C8) and the common W324L zhf1 mutation (B1) were introduced into the unmutagenized MDR-sup S. pombe strain by homologous recombination. The resulting strains, which were shown by PCR amplicon sequencing to harbor the desired mutation, were all found to be resistant to indolotryptolines at the same level as the randomly mutagenized clones containing the same mutation (Figure S2 of the Supporting Information). The individual vma3, vma11, and zhf mutations we detected are therefore necessary and sufficient for conferring resistance to indolotryptoline-based compounds.

Acidic Staining of Vacuoles

As the V-ATPase is responsible for maintaining the acidification of cellular organelles, V-ATPase activity can be monitored in whole cells by using acidic staining dyes (e.g., quinacrine) that form fluorescent puncta in vacuoles at reduced pH.35,36 Similar to the known plecomacrolide-type V-ATPase inhibitors, bafilomycin and concanamycin, indolotryptolines also prevented the formation of fluorescent puncta in the cells in a dose-dependent manner, while the presence of brefeldin (protein transport inhibitor) had no effect (Figure 4A). Whole-cell V-ATPase inhibition by indolotryptolines (MICs of 69 nM for BE-54017 and 143 nM for cladoniamide A) occurs at concentrations similar to those needed for whole-cell cytotoxicity (MICs of 35 nM for BE-54017 and 72 nM for cladoniamide A). In addition, acidic staining experiments were conducted using strains containing each unique vma3 (B7, B12, and C8) and vma11 (B10 and C6) mutation, as well as a representative strain with the common W324L zhf1 (B1) mutation (Figure 4B and Figure S3 of the Supporting Information). All vma3 and vma11 mutants showed increased tolerance to the disruption of puncta by indolotryptolines, while the zhf1 mutant responded like nonmutant MDR-sup in these experiments.

Figure 4.

Visualization of whole-cell V-ATPase activity by acidic organelle staining. (A) Nomarski and fluorescent images of quinacrine-stained unmutagenized MDR-sup S. pombe upon incubation with BE-54017 (BE) or brefeldin A (Bre). The formation of fluorescent puncta is inhibited at higher concentrations of BE, with no puncta observed in >95% of the cells at 69 nM, which is defined as the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of V-ATPase activity (red). Bre has no effect on puncta formation. (B) Summary of the fold difference in whole-cell V-ATPase MIC relative to unmutagenized MDR-sup. Cla, cladoniamide A. See also Figure S3 and Table S3 of the Supporting Information.

V-ATPase Inhibition in the Presence of Zinc

As Zhf1 is responsible for controlling zinc homeostasis, in particular in regulating the zinc concentration in the endoplasmic reticulum and nucleus, we tested the relationship between indolotryptoline toxicity and zinc concentration. In these assays, we observed that MDR-sup S. pombe becomes more sensitive to BE-54017 and cladoniamide A with increasing concentrations of zinc in the growth medium (Figure 5). This effect is similarly observed with the known V-ATPase inhibitors, bafilomycin and concanamycin, but not with the protein transport inhibitor, brefeldin.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity of the unmutagenized MDR-sup S. pombe to cytotoxins in the presence of increasing concentrations of zinc. (A) Summary of fold differences in whole-cell cytotoxicity (IC50) relative to media without the addition of ZnCl2. (B) Dose response curve for unmutagenized MDR-sup when it is exposed to BE-54017 in the presence of different concentrations of ZnCl2. In the tested ZnCl2 concentration range (0.01–0.2 mM), zinc has no effect on the apparent growth rate of MDR-sup S. pombe in the absence of any cytotoxins. See also Table S3 of the Supporting Information.

Cross-Resistance

Indolotryptoline resistant strains were tested for cross-resistance to the well-characterized plecomacrolide-type V-ATPase inhibitors, bafilomycin and concanamycin (Figure 3 and Figure S1 of the Supporting Information). The W324L Zhf1 mutant confers resistance to both of the known V-ATPase inhibitors. With the exception of the M130I Vma3 (C8) mutant, which confers a 2-fold increase in resistance to bafilomycin, V-ATPase mutants did not show cross-resistance to either bafilomycin or concanamycin.

Mapping of the Putative Indolotryptoline Proteolipid-Binding Site

The V-ATPase is a multiprotein complex that consists of two domains: a peripheral ATP-binding domain (V1) and a membrane-associated proton translocating pore domain (V0) (Figure 6A).19,20 In yeast, the V0 domain contains a hexameric cylinder that is known as the proteolipid ring. The catalytic V1 subunit hydrolyzes ATP, which drives the rotation of the proteolipid ring that in turn allows for protons to translocate across the membrane. The proteolipid ring is thought to be composed of c (vma3), c′ (vma11), and c″ (vma16) subunits that assemble in a 4:1:1 (c:c′:c″) stoichiometry.19,20,37 As is the case with plecomacrolide resistance-conferring mutations, indolotryptoline-conferring mutations are found in the proteolipid subunits.

Figure 6.

Structure of V-ATPase. (A) Schematic of yeast V-ATPase architecture, which consists of the catalytic V1 domain (green) and the membrane-translocating V0 domain (yellow and beige). Proteolipid subunits c, c′, and c″ (beige) are part of the V0 domain and form a hexameric ring structure. (B–D) Side, close-up, and top views, respectively, of the crystal structure of a proteolipid subunit from the E. hirae V-ATPase (PDB entry 2BL2). The peptide backbone is represented as a green stick model. Residues found to be involved in conferring resistance to indolotryptolines are colored red. Residues reported in previous studies to be involved in plecomacrolide resistance are colored blue.37 See also Figure S4 of the Supporting Information.

The detailed molecular structure of the yeast V-ATPase is not known; however, the proteolipid substructure from the vacuolar Na+-ATPase from the bacterium E. hirae has been determined by X-ray crystallography.38 Despite phylogenetic and functional differences, the high degree of sequence homology seen between the E. hirae proteolipid subunits and those found in eukaryotic V-ATPase complexes has led to the use of the E. hirae V-ATPase structure as a model for eukaryotic V-ATPase studies. In particular, the residues that confer resistance to V-ATPase inhibitors have been mapped onto the E. hirae V-ATPase structure to predict putative inhibitor-binding sites.37,39 Residues reported to confer resistance to plecomacrolide-like inhibitors generally cluster midway between the cytoplasmic and luminal faces of the proteolipid ring and point out from the four-helix bundle that makes up each of the proteolipid subunits.37 In contrast, indolotryptoline resistance-conferring mutations map near the cytoplasmic face and mostly point into the center of the bundle (Figure 6 and Figure S4 of the Supporting Information).

Discussion

Through whole-genome sequencing of indolotryptoline resistant mutants, we identified point mutations in the proteolipid (c/c′) subunits of V-ATPase and the zinc transporter Zhf1 that conferred resistance to this family of natural products. Previous studies have observed a tight functional connection between zinc toxicity and V-ATPase activity. The inactivation of the V-ATPase in diverse organisms from yeasts to plants, by either a gene knockout or a small-molecule inhibitor, is known to result in increased sensitivity to zinc, indicating that the V-ATPase plays a critical role in zinc homeostasis and that zinc toxicity is likely the principal downstream deleterious consequence of V-ATPase inhibition.40−42 As would be expected for a V-ATPase inhibitor, we observed that MDR-sup S. pombe becomes more sensitive to indolotryptolines in the presence of increasing concentrations of zinc.

Although V-ATPase activity in budding yeast (Sa. cerevisiae) has been investigated in vitro using isolated vacuolar membranes,43 the purification of similar membrane fractions from S. pombe has proven to be challenging, thereby precluding comparable in vitro biochemical analyses of these mutants.44 However, because the V-ATPase is responsible for maintaining the acidification of cellular organelles, V-ATPase activity in whole cells can be monitored using acidic staining dyes.35,36 As previously reported for known V-ATPase inhibitors,45,46 the addition of indolotryptolines to culture media at subminimal inhibitory concentrations resulted in the loss of fluorescent puncta formation in a dose-dependent manner in unmutagenized MDR-sup S. pombe (Figure 5A), confirming the inhibition of V-ATPase activity in the presence of indolotryptolines. The fact that our indolotryptoline resistance-conferring V-ATPase mutants are largely compound class specific, while Zhf1 mutants confer resistance irrespective of the compound class, further suggests a model in which zinc toxicity is a downstream deleterious consequence of V-ATPase inhibition in the presence of indolotryptoline natural products. Ultimately, the in vitro biochemical reconstitution of mutant and wild-type human V-ATPase will be necessary to definitively confirm V-ATPase as the molecular target of indolotryptolines in human cells.

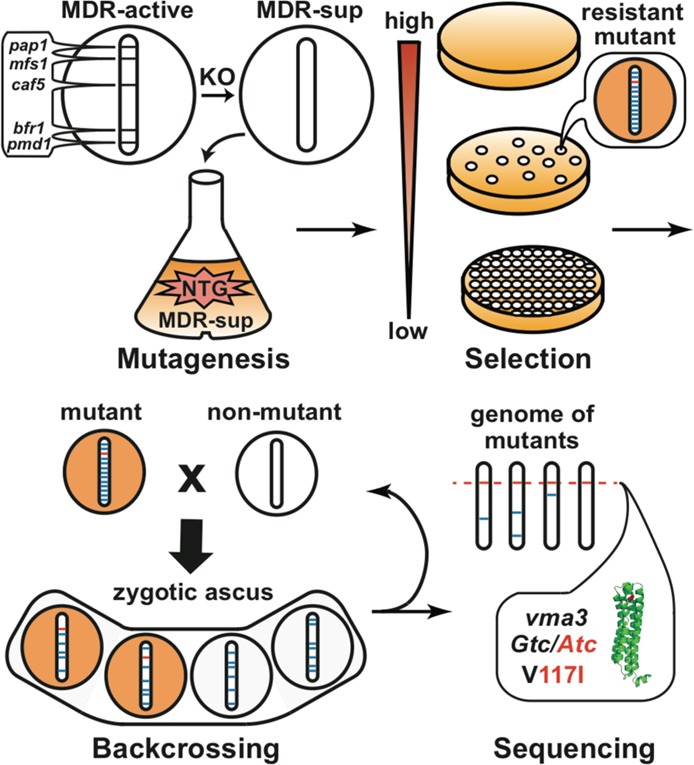

The V-ATPase is a highly conserved protein complex in eukaryotes that plays a role in acidifying a variety of organelles.19,20 V-ATPase inhibitors have been explored as cancer therapeutic agents because of their cytotoxicity toward diverse cancer cell lines.47,48 Cell lines from cancers that are especially malignant, aggressive, and unresponsive to current therapies are known to be sensitive to V-ATPase inhibitors, possibly because of the involvement of an acid microenvironment in tumor progression and multidrug resistance.21,22 On the basis of the fact that four of the five vma3/11 mutations that confer resistance to indolotryptolines do not show cross-resistance to plecomacrolide-type metabolites and that the fifth mutation confers only low-level resistance to bafilomycin (Figure 3), the indolotryptoline-binding site is likely distinct from the plecomacrolide-binding pocket in the proteolipid ring. On the basis of the significant structural differences between indolotryptolines and known V-ATPase inhibitors (Figure 7),49 it would not be surprising that they bind at a distinct site and therefore have selected for unique resistance-conferring mutations. The potential existence of a unique indolotryptoline V-ATPase-binding site suggests that these natural products can serve as the inspiration for the development of a new class of nanomolar V-ATPase inhibitors that can be explored for anticancer activity.

Figure 7.

Chemical structures of previously characterized V-ATPase inhibitors.

Tryptophan dimers, in particular the closely related indolocarbazole family of natural products, have been observed to interact with proteins containing nucleotide-binding sites (i.e., ATP or DNA) through mimicry of a nucleotide base.13,15−17 While the V-ATPase uses ATP, the proteolipid subunits of V-ATPase are not known to contain a nucleotide-binding site, suggesting that tryptophan dimer-binding motifs might extend beyond simple nucleotide mimicry. Disruption of the planar indolocarbazole ring system through the sp3 hybridization of the two carbons at the base of the pyrrole ring in the indolotryptoline structure is likely to lead to an altered mode of binding of this class of tryptophan dimers. Eventually, an indolotryptoline–proteolipid cocrystal structure will be required to confirm this change in binding motif hypothesis.

Any molecular target elucidated in a model organism like S. pombe must ultimately be confirmed in human cancer cells if relevance to cancer therapy is to be established. Nevertheless, resistant mutant selection of MDR-sup S. pombe provides the means for developing mode of action hypotheses that do not require any chemical modification of the bioactive compound, preliminary prediction of the target, or construction of a custom-made genetic library, thereby serving as a convenient alternative approach for target identification studies of cytotoxic natural products. The characterization of a cytotoxic natural product’s molecular target using human cells has traditionally been costly, time-consuming, and technically cumbersome. Resistant mutant screening using MDR-sup S. pombe should serve as a powerful and generally applicable alternative target identification technique that fits nicely into diverse drug discovery pipelines for gene-level target identification and validation of cytotoxins.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tarun M. Kapoor for the generous gift of S. pombe strains.

Supporting Information Available

Complete whole-cell cytotoxicity dose response curves, targeted mutagenesis data, complete V-ATPase activity data, and protein sequence alignment of resistance-conferring mutations (Figures S1–S4, respectively) and S. pombe strain list, PCR primer list, and summary of IC50 and MIC values (Tables S1-S3, respectively). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM077516. S.F.B. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Scientist.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Ryan K. S.; Drennan C. L. (2009) Divergent pathways in the biosynthesis of bisindole natural products. Chem. Biol. 16(4), 351–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang F. Y.; Brady S. F. (2011) Cloning and characterization of an environmental DNA-derived gene cluster that encodes the biosynthesis of the antitumor substance BE-54017. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133(26), 9996–9999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y. L.; Ding T.; Patrick B. O.; Ryan K. S. (2013) Xenocladoniamide F, minimal indolotryptoline from the cladoniamide pathway. Tetrahedron Lett. 54(41), 5635–5638. [Google Scholar]

- Nakase K.; Nakajima S.; Hirayama M.; Kondo H.; Kojiri K.; Suda H.. JP 2000178274, 2000.

- Williams D. E.; Davies J.; Patrick B. O.; Bottriell H.; Tarling T.; Roberge M.; Andersen R. J. (2008) Cladoniamides A-G, tryptophan-derived alkaloids produced in culture by Streptomyces uncialis. Org. Lett. 10(16), 3501–3504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg G. M.; Grothaus P. G.; Newman D. J. (2009) Impact of natural products on developing new anti-cancer agents. Chem. Rev. 109(7), 3012–3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd M. R.; Paull K. D. (1995) Some practical considerations and applications of the national cancer institute in vitro anticancer drug discovery screen. Drug Dev. Res. 34(2), 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Du Y. L.; Ding T.; Ryan K. S. (2013) Biosynthetic O-methylation protects cladoniamides from self-destruction. Org. Lett. 15(10), 2538–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngernmeesri P.; Soonkit S.; Konkhum A.; Kongkathip B. (2014) Formal synthesis of (±)-cladoniamide G. Tetrahedron Lett. 55(9), 1621–1624. [Google Scholar]

- Loosley B. C.; Andersen R. J.; Dake G. R. (2013) Total synthesis of cladoniamide G. Org. Lett. 15(5), 1152–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang F. Y.; Brady S. F. (2013) Discovery of indolotryptoline antiproliferative agents by homology-guided metagenomic screening. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110(7), 2478–2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speck K.; Magauer T. (2013) The chemistry of isoindole natural products. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 9, 2048–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez C.; Mendez C.; Salas J. A. (2006) Indolocarbazole natural products: Occurrence, biosynthesis, and biological activity. Nat. Prod. Rep. 23(6), 1007–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M. S. (2005) Natural products to drugs: Natural product derived compounds in clinical trials. Nat. Prod. Rep. 22(2), 162–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano H.; Omura S. (2009) Chemical biology of natural indolocarbazole products: 30 years since the discovery of staurosporine. J. Antibiot. 62(1), 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prade L.; Engh R. A.; Girod A.; Kinzel V.; Huber R.; Bossemeyer D. (1997) Staurosporine-induced conformational changes of cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit explain inhibitory potential. Structure 5(12), 1627–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staker B. L.; Feese M. D.; Cushman M.; Pommier Y.; Zembower D.; Stewart L.; Burgin A. B. (2005) Structures of three classes of anticancer agents bound to the human topoisomerase I-DNA covalent complex. J. Med. Chem. 48(7), 2336–2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T.; Kanagaki S.; Matsui Y.; Imoto M.; Watanabe T.; Shibasaki M. (2012) Synthesis and assignment of the absolute configuration of indenotryptoline bisindole alkaloid BE-54017. Org. Lett. 14(17), 4418–4421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies K. C.; Cipriano D. J.; Forgac M. (2008) Function, structure and regulation of the vacuolar (H+)-ATPases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 476(1), 33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benlekbir S.; Bueler S. A.; Rubinstein J. L. (2012) Structure of the vacuolar-type ATPase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae at 11-Å resolution. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19(12), 1356–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Sayans M.; Somoza-Martin J. M.; Barros-Angueira F.; Rey J. M.; Garcia-Garcia A. (2009) V-ATPase inhibitors and implication in cancer treatment. Cancer Treat. Rev. 35(8), 707–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spugnini E. P.; Citro G.; Fais S. (2010) Proton pump inhibitors as anti vacuolar-ATPases drugs: A novel anticancer strategy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenone M.; Dancik V.; Wagner B. K.; Clemons P. A. (2013) Target identification and mechanism of action in chemical biology and drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9(4), 232–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler S.; Pries V.; Hedberg C.; Waldmann H. (2013) Target identification for small bioactive molecules: Finding the needle in the haystack. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 52(10), 2744–2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill A. J.; Chopra I. (2004) Preclinical evaluation of novel antibacterial agents by microbiological and molecular techniques. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 13(8), 1045–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado M. A.; Rintoul M. R.; Farias R. N.; Salomon R. A. (2001) Escherichia coli RNA polymerase is the target of the cyclopeptide antibiotic microcin J25. J. Bacteriol. 183(15), 4543–4550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg C.; Brunner N. A.; Schiffer G.; Lampe T.; Pohlmann J.; Brands M.; Raabe M.; Habich D.; Ziegelbauer K. (2004) Identification and characterization of the first class of potent bacterial acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibitors with antibacterial activity. J. Biol. Chem. 279(25), 26066–26073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffeau A.; Barrell B. G.; Bussey H.; Davis R. W.; Dujon B.; Feldmann H.; Galibert F.; Hoheisel J. D.; Jacq C.; Johnston M.; Louis E. J.; Mewes H. W.; Murakami Y.; Philippsen P.; Tettelin H.; Oliver S. G. (1996) Life with 6000 genes. Science 274(5287), 546., 563–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood V.; Gwilliam R.; Rajandream M. A.; Lyne M.; Lyne R.; Stewart A.; Sgouros J.; Peat N.; Hayles J.; Baker S.; Basham D.; Bowman S.; Brooks K.; Brown D.; Brown S.; Chillingworth T.; Churcher C.; Collins M.; Connor R.; Cronin A.; Davis P.; Feltwell T.; Fraser A.; Gentles S.; Goble A.; Hamlin N.; Harris D.; Hidalgo J.; Hodgson G.; Holroyd S.; Hornsby T.; Howarth S.; Huckle E. J.; Hunt S.; Jagels K.; James K.; Jones L.; Jones M.; Leather S.; McDonald S.; McLean J.; Mooney P.; Moule S.; Mungall K.; Murphy L.; Niblett D.; Odell C.; Oliver K.; O’Neil S.; Pearson D.; Quail M. A.; Rabbinowitsch E.; Rutherford K.; Rutter S.; Saunders D.; Seeger K.; Sharp S.; Skelton J.; Simmonds M.; Squares R.; Squares S.; Stevens K.; Taylor K.; Taylor R. G.; Tivey A.; Walsh S.; Warren T.; Whitehead S.; Woodward J.; Volckaert G.; Aert R.; Robben J.; Grymonprez B.; Weltjens I.; Vanstreels E.; Rieger M.; Schafer M.; Muller-Auer S.; Gabel C.; Fuchs M.; Dusterhoft A.; Fritzc C.; Holzer E.; Moestl D.; Hilbert H.; Borzym K.; Langer I.; Beck A.; Lehrach H.; Reinhardt R.; Pohl T. M.; Eger P.; Zimmermann W.; Wedler H.; Wambutt R.; Purnelle B.; Goffeau A.; Cadieu E.; Dreano S.; Gloux S.; Lelaure V.; Mottier S.; Galibert F.; Aves S. J.; Xiang Z.; Hunt C.; Moore K.; Hurst S. M.; Lucas M.; Rochet M.; Gaillardin C.; Tallada V. A.; Garzon A.; Thode G.; Daga R. R.; Cruzado L.; Jimenez J.; Sanchez M.; del Rey F.; Benito J.; Dominguez A.; Revuelta J. L.; Moreno S.; Armstrong J.; Forsburg S. L.; Cerutti L.; Lowe T.; McCombie W. R.; Paulsen I.; Potashkin J.; Shpakovski G. V.; Ussery D.; Barrell B. G.; Nurse P. (2002) The genome sequence of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nature 415(6874), 871–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfger H.; Mamnun Y. M.; Kuchler K. (2001) Fungal ABC proteins: Pleiotropic drug resistance, stress response and cellular detoxification. Res. Microbiol. 152(3–4), 375–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima S. A.; Takemoto A.; Nurse P.; Kapoor T. M. (2012) Analyzing fission yeast multidrug resistance mechanisms to develop a genetically tractable model system for chemical biology. Chem. Biol. 19(7), 893–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoi Y.; Sato M.; Sutani T.; Shirahige K.; Kapoor T. M.; Kawashima S. A. (2014) Dissecting the first and the second meiotic divisions using a marker-less drug-hypersensitive fission yeast. Cell Cycle 13(8), 1327–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima S. A.; Takemoto A.; Nurse P.; Kapoor T. M. (2013) A chemical biology strategy to analyze rheostat-like protein kinase-dependent regulation. Chem. Biol. 20(2), 262–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfa C., Fantes P., Hyams J., McLeod M., and Warbrick E. (1993) Experiments with Fission Yeast, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Iwaki T.; Goa T.; Tanaka N.; Takegawa K. (2004) Characterization of Schizosaccharomyces pombe mutants defective in vacuolar acidification and protein sorting. Mol. Genet. Genomics 271(2), 197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C. J.; Raymond C. K.; Yamashiro C. T.; Stevens T. H. (1991) Methods for studying the yeast vacuole. Methods Enzymol. 194, 644–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman B. J.; McCall M. E.; Baertsch R.; Bowman E. J. (2006) A model for the proteolipid ring and bafilomycin/concanamycin-binding site in the vacuolar ATPase of Neurospora crassa. J. Biol. Chem. 281(42), 31885–31893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T.; Yamato I.; Kakinuma Y.; Leslie A. G.; Walker J. E. (2005) Structure of the rotor of the V-type Na+-ATPase from Enterococcus hirae. Science 308(5722), 654–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockelmann S.; Menche D.; Rudolph S.; Bender T.; Grond S.; von Zezschwitz P.; Muench S. P.; Wieczorek H.; Huss M. (2010) Archazolid A binds to the equatorial region of the c-ring of the vacuolar H+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 285(49), 38304–38314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDiarmid C. W.; Milanick M. A.; Eide D. J. (2002) Biochemical properties of vacuolar zinc transport systems of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 277(42), 39187–39194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi M.; Kobae Y.; Mimura T.; Maeshima M. (2008) Deletion of a histidine-rich loop of AtMTP1, a vacuolar Zn2+/H+ antiporter of Arabidopsis thaliana, stimulates the transport activity. J. Biol. Chem. 283(13), 8374–8383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melin P.; Schnurer J.; Wagner E. G. (2004) Disruption of the gene encoding the V-ATPase subunit A results in inhibition of normal growth and abolished sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiology 150(Part 3), 743–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane P. M.; Yamashiro C. T.; Stevens T. H. (1989) Biochemical characterization of the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 264(32), 19236–19244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongcharoen P.; Kawano-Kawada M.; Iwaki T.; Sugimoto N.; Sekito T.; Akiyama K.; Takegawa K.; Kakinuma Y. (2013) Functional expression of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Vba2p in the vacuolar membrane of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem. 77(9), 1988–1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M.; Tarsio M.; Charsky C. M.; Kane P. M. (2005) Structural and functional separation of the N- and C-terminal domains of the yeast V-ATPase subunit H. J. Biol. Chem. 280(44), 36978–36985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marceau F.; Bawolak M. T.; Bouthillier J.; Morissette G. (2009) Vacuolar ATPase-mediated cellular concentration and retention of quinacrine: A model for the distribution of lipophilic cationic drugs to autophagic vacuoles. Drug Metab. Dispos. 37(12), 2271–2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman E. J.; Bowman B. J. (2005) V-ATPases as drug targets. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 37(6), 431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fais S.; De Milito A.; You H. Y.; Qin W. X. (2007) Targeting vacuolar H+-ATPases as a new strategy against cancer. Cancer Res. 67(22), 10627–10630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huss M.; Wieczorek H. (2009) Inhibitors of V-ATPases: Old and new players. J. Exp. Biol. 212(Part 3), 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.