SUMMARY

Spatial patterns of functional organization, resolved by microelectrode mapping, comprise a core principle of sensory cortices. In auditory cortex, however, recent two-photon Ca2+ imaging challenges this precept, as the traditional tonotopic arrangement appears weakly organized at the level of individual neurons. To resolve this fundamental ambiguity about the organization of auditory cortex, we developed multiscale optical Ca2+ imaging of unanesthetized GCaMP transgenic mice. Single-neuron activity monitored by two-photon imaging was precisely registered to large-scale cortical maps provided by transcranial wide field imaging. Neurons in the primary field responded well to tones, neighboring neurons were appreciably co-tuned, and preferred frequencies adhered tightly to a tonotopic axis. By contrast, nearby secondary-field neurons exhibited heterogeneous tuning. The multiscale imaging approach also readily localized vocalization regions and neurons. Altogether, these findings cohere electrode and two-photon perspectives, resolve new features of auditory cortex, and offer a promising approach generalizable to any cortical area.

INTRODUCTION

The functional organization of primary sensory cortices (e.g., visual, somatosensory, and auditory) often mirrors the spatial organization of their peripheral sensing organs (Kaas, 1997, 2011). The resulting functional maps of cortex have proven invaluable, both to compare recording locations across experiments and to track an operational correlate of synaptic plasticity (Buonomano and Merzenich, 1998; de Villers-Sidani et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2012; Karmarkar and Dan, 2006). Nonetheless, the supporting data for these maps has often drawn from methods that average activity across multiple neurons; thus, the extent to which these canonical maps pertain to individual neurons remains to be determined.

In particular, these maps have traditionally been resolved by extracellular electrode recordings, densely sampled across a large cortical area with accurate spike detection. Alternatively, a complementary view has come from wide field optical imaging that simultaneously surveys expansive cortical regions. For instance, to gauge neural tissue activity, these approaches monitor local changes in blood flow or altered flavoprotein oxidation (Honma et al., 2013; Takahashi et al., 2006); alternatively, regions of depolarization may be directly detected via voltage-sensitive dyes bulk-loaded into neuropil (Grinvald and Hildesheim, 2004). While these spatially expansive approaches provide holistic global maps, they are often limited by low signal fidelity and spatial resolution. Most recently, two-photon Ca2+ imaging has promised major advances at an intermediate scale, enabling simultaneous monitoring of large numbers of neurons within a local region (Andermann et al., 2011; Ohki et al., 2005; Svoboda and Yasuda, 2006). This approach has the potential to expand our knowledge of the functional organization of cortex.

For auditory cortex, however, paradoxical observations have emerged between methods. Electrode recordings consistently substantiate a cochleotopic organization. This arrangement—also referred to as spectral organization or tonotopy—originates from the base-to-apex selectivity of the cochlea for decreasing frequencies of incoming sound (Pickles, 2012). This spectral organization is subsequently maintained through much of the auditory system (Hackett et al., 2011; Kaas, 2011). In mouse cortex, the primary auditory fields (AI, primary auditory cortex; and AAF, anterior auditory field) contain best-frequency spatial gradients (tonotopic axes) that mirror each other (Guo et al., 2012; Hackett et al., 2011; Joachimsthaler et al., 2014; Stiebler et al., 1997). Other auditory fields are less well-characterized; these include the ultrasonic field (UF), which responds to high-frequency sounds and may be an extension of dorsorostral AI (Guo et al., 2012), and the secondary auditory field (AII), which sits ventral to the primary fields and may not be spectrally organized (Stiebler et al., 1997). Instead, AII has been theorized to support higher-order novelty and sound-object processing (Geissler and Ehret, 2004; Joachimsthaler et al., 2014).

By contrast, recent two-photon Ca2+ imaging of individual neurons in AI and AAF, using Ca2+-sensitive dyes bulk loaded into tissue, paints a different picture. Tuning of individual neurons is often poor, with only weak responsiveness over a broad frequency range. Moreover, frequency tuning of neighboring neurons (<100–200 μm apart) is largely uncorrelated, with best frequencies varying by up to 3–4 octaves (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2011; Rothschild et al., 2010). Finally, an overall tonotopic axis that spans AI is only negligibly (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2010) or inconsistently (Rothschild et al., 2010) resolved over larger distances, with strikingly poorer correlations observed between preferred frequency and position along a tonotopic axis, compared to microelectrode studies (Table S1). This discord—between the strong tonotopy observed over decades of electrode recordings versus the diverse and weak tonal selectivity measured with two-photon Ca2+ imaging—presents a key hurdle to leveraging the two-photon approach to define cortical circuits and raises questions about the spectral organization of auditory cortex (Guo et al., 2012), particularly as it relates to experience-dependent plasticity of tonotopic maps (de Villers-Sidani and Merzenich, 2011). Potential explanations include actual differences in the neurons interrogated by the two techniques, effects of anesthesia that disproportionately mute signal detection by Ca2+ imaging (Wang, 2007), or inadvertent two-photon imaging of regions outside intended loci.

We therefore develop a preparation that enables two-photon Ca2+ imaging of mouse auditory cortex in unanesthetized mice to preserve cortical activity. Also crucial is our use of a transgenic mouse in which neuronal expression of the genetically-encoded Ca2+ indicator GCaMP3 is controlled by the Cre-Lox system (Tian et al., 2009; Zariwala et al., 2012). This approach furnishes widespread expression of GCaMP3 in a manner reproducible across cortices and mice, aiding comparison across large sectors of auditory cortex. Of equal importance, we discover that GCaMP3-expressing mice permit robust transcranial wide field imaging of auditory cortical activity, allowing resolution of a global functional map before undertaking two-photon Ca2+ imaging to interrogate individual neurons. These global maps can be delineated from only a single-trial set of tone presentations, enabling rapid registration of individual neurons to their precise locations within a global map. With these advances, we reconcile the conflicting perspectives on tonotopicity of AI, discover previously unknown organizational features of AII, and identify vocalization-responsive regions and neurons. Our approach—Ca2+ imaging across multiple spatial scales in functional mapping experiments—may be generalized for studying coding and functional organization in any sensory cortex.

RESULTS

GCaMP-Based Transcranial Functional Imaging

We sought a convenient method for macroscopic mapping of auditory cortex, a strategy that would allow rapid and definitive subsequent registration of individual neurons interrogated under in vivo two-photon Ca2+ imaging. For this purpose, we utilized unanesthetized transgenic mice expressing GCaMP3 in neurons (Syn1-Cre; R26-lsl-GCaMP3 or Emx1-Cre; R26-lsl-GCaMP3) (Zariwala et al., 2012)). Using immunohistochemistry and Ca2+ imaging, we verified that GCaMP3 expression was predominantly in neurons rather than in glia (Figures S1 and S7A–C). After exposing and thinning the skull overlying left auditory cortex, we performed wide field epifluorescence imaging on restrained, head-fixed mice (Figure 1A). The baseline fluorescence ‘scout’ image shows the overall field, which spans a ~4 mm2 area (Figure 1B). Blood vessels are clearly resolved in black, which serve as useful guides for subsequent registration. In response to sinusoidal amplitude modulated (SAM) tones delivered to the right ear, we routinely resolved single-trial fluorescence responses of sizeable magnitude (~5% ΔF/FO with standard deviation ~0.3% ΔF/FO, metrics averaged from three mice). This profile grants signal-to-noise ratios of ~15 (Figures 1C and S2A–C) and standard deviations of ~1% across trials (Figure S2D). The fluorescence signals displayed in the upper rows of Figure 1C correspond to the three regions marked in Figure 1B, and the affiliated tone presentations are registered below by blips. For comparison, we also considered the use of an established approach to transcranial macroscopic imaging based on flavoprotein fluorescence (Takahashi et al., 2006). Our own attempts at such imaging yielded transients of ~0.1% ΔF/FO and a signal-to-noise ratio of ~1 (not shown). Thus, GCaMP3-based imaging represented a crucial enabling advantage for the present study.

Figure 1. Transcranial responses to SAM tones in GCaMP3 mice.

(A) Transcranial Ca2+ imaging layout. Speaker emits SAM (sinusoidal amplitude modulated) tones to right ear of head-fixed, unanesthetized mouse. 470-nm excitation illuminates thinned skull over left auditory cortex (gray circle). 525-nm emission collected by CCD camera.

(B) Average transcranial fluorescence image from exemplar mouse, expressing GCaMP3 under Emx1-Cre driver line. Vasculature landmarks are low signal.

(C) Ca2+ activity induced by SAM tones at three regions marked in panel B. Upper 3 rows, single-trial fluorescence responses. SAM tones delivered every 2 secs, covering 5-octave range in random order. For convenience, traces here sorted by increasing frequency, as labeled on bottom. Original baseline-corrected signal in gray and sparse-encoding waveform in black.

(D) Ca2+ activity over entire auditory region during presentation of low, middle, and high-frequency tones. Images displayed in grayscale format (equivalent ΔF/FO scale bar, lower right) after processing by sparse-encoding algorithm and deblurring. Loci of strongest response to low (L) and high (H) frequency tones marked on 3 and 30 kHz images, respectively. Dorsal-caudal spatial scale bar on lower left denotes 300 μm along each dimension.

(B–D) Data from same mouse.

We next investigated the spatial organization of these signals. Indeed, responses to different tone frequencies were spatially distinct in the same mouse (Figures 1D and S2E–F). In particular, low-frequency stimuli elicited spatially restricted responses in the three regions (‘poles’) within the leftmost subpanel of Figure 1D (labeled ‘L’). By contrast, high-frequency sounds elicited responses in four different poles, labeled ‘H’ in the rightmost subpanel of Figure 1D. As might be expected, tone presentation of middle frequencies evoked peak responses at intermediate positions (Figure 1D, middle subpanel). As the locations of these ‘L’ and ‘H’ poles were largely consistent across different sound levels and tone durations (Figure S3), we used the local center-of-mass of pole activities as landmarks for subsequent registration of two-photon imaging fields. Details on forming these transcranial signals and images (Figures 1C–D) are described in online Experimental Procedures (Transcranial Image Analysis) and Figure S2.

To form a detailed spatial map of spectral tuning from such images, we calculated a preferred frequency at each pixel. First, we recorded response images across a range of sound levels and frequencies as shown by the thumbnail image collage in Figure 2A. The images were processed as in Figure 1D, but shown with an inverted grayscale format for clarity at reduced display size. Sound attenuation is graded along the y axis and frequency along the x axis. Second, based on these responses, we selected the weakest sound level that elicited a response for the field as a whole, yielding the jagged border line in Figure 2A. Reassuringly, this estimate of cortical threshold versus frequency accords well with other measures of hearing thresholds in C57BL/6 mice (Mikaelian et al., 1974; Taberner and Liberman, 2005) (Figure S4A). Third, at each pixel, a weighted average of the frequencies eliciting the largest responses provided an estimate of the preferred frequency. For visualizing these tuning preferences, we formed the map shown in Figure 2B, where hue indicates preferred frequency and color saturation indicates response strength. Weakly responsive regions appear as white pixels. As expected, this detailed map (Figure 2B) agrees well with the landmarks chosen for low- and high-frequency stimuli (Figure 1D). Importantly, transcranial maps could be reproducibly obtained across mice (Figure 2C), as shown by maps from two other mice (M2 and M7). After adjusting for differences in landmark positions between mice via elastic registration (Figure S5), averaging seven maps yielded a canonical arrangement (Figure 2D). The resemblance of this meta configuration to that of individual mice (Figures 2B and 2C) substantiates the reproducibility of maps across mice.

Figure 2. Formation of transcranial map of auditory cortices.

(A) Single-trial transcranial fluorescence responses during SAM tones of various frequencies (x axis) and sound attenuations (y axis, left). SPL intensities, y axis on right, coarsely corrected for speaker calibration. Images as in Figure 1D, but plotted as inverted grayscale format (equivalent ΔF/FO scale bar, lower right). Jagged thin black line indicates approximate threshold, lowest sound level eliciting responses at given frequency. Signals below threshold reflect spontaneous activity. Mouse expressing GCaMP3 under Syn1-Cre driver line.

(B) Best-frequency map for the same experiment. Each pixel plots a color-map readout of weighted average of 3 frequencies eliciting largest responses at threshold sound level. Color map (lower right) associates best frequencies (y axis) with specific colors (e.g., blue = low, red = high); color saturation (x axis) denotes strength of best-frequency responses. Low- and high-frequency hotspots (L and H labels, respectively), determined as local center-of-mass coordinates calculated over low- and high-frequency islands, serve as landmarks throughout. Dorsal-caudal spatial scale bar on lower left denotes 300 μm along each dimension.

(C) Transcranial response maps as in panel B, for 2 other mice (M2 and M7). Slight differences exist in colors and precise layout of landmarks, but overall features and low-to-high frequency gradients are preserved. Mice expressing GCaMP3 under Emx1-Cre (M2) and Syn1-Cre (M7).

(D) Average of 7 transcranial response maps, including those in panels B–C, demonstrating conserved canonical layout across mice. Landmark-based registration morphs each individual map onto a common coordinate system before averaging (see Figure S5).

(E) Global map from panel B, with dark-thick-line paths of maximally responsive loci (local center-of-mass) with increasing frequencies. Trajectories derived from solid arrows in panel F.

(F) Coarse schematic of mouse auditory cortex, from transcranial imaging of mouse M1. Solid lines with arrows, best fits to data; dashed lines with arrows, poorer fits. Details in Figure S4.

This reproducibility allowed for analysis of additional features of spectral organization (Figure 2E, corresponding to the merged field in Figure 2D). In particular, we resolved four low-to-high frequency gradients, depicted as thick black L→H trajectories in Figure 2E, where each gradient is here defined by the trajectory of local maxima of Ca2+ activity with increasing tone frequency (Figure S4). These gradients and the high- and low-frequency poles permitted identification of the likely locations of AI/UF, AAF, and AII (Figure 2F), as follows. For AI, two gradients travelled rostrally. The dorsal branch terminated in UF, consistent with recent extensive microelectrode mapping (Guo et al., 2012). The ventral branch moved towards AII, and may be a new observation in mice. For AAF, the traditional tonotopic axis defined by microelectrode mapping would extend from the low-frequency pole in AAF to the high-frequency pole in UF (Guo et al., 2012), as depicted by the dashed arrow connecting AAF ‘L’ with UF ‘H’ in Figure 2F. Importantly, however, the traditional gradient traces a path tracking the steepest rate of change in preferred frequency with distance (Guo et al., 2012), regardless of comparative response strength. If we were to use a similar definition, this tone axis would be present in our data along the dashed arrow in Figure 2F. However, we often observed comparatively weak responsiveness along this path. Accordingly, for purposes of robust fiducial orientation, we favored calculation of the ventrally directed L→H gradient in AAF (Figures 2E and 2F), which tracks local maxima of response strength. Reassuringly, this ventrally directed gradient concurs with results from intrinsic imaging methods (Honma et al., 2013). Finally, for AII, the robust activity we monitor under transcranial Ca2+ imaging enabled observation of a dorsoventral gradient (Figures 2E and 2F), a feature not previously discerned in electrode studies using anesthesia (Guo et al., 2012).

Ca2+ responses of individual neurons registered to AI

Following acquisition of a global transcranial activity map, we performed a craniotomy over the left auditory cortex and undertook two-photon Ca2+ imaging of individual neurons at depths of 150 to 430 μm (Figure S1Q), with most neurons residing within layers II/III. Figure 3 displays the results for a single exemplar neuron. Panel A outlines the registration of this neuron to the low-frequency pole of AI. The transcranial map for this mouse is displayed in the left subpanel, and the relevant two-photon field is shown in the middle subpanel (exemplar neuron boxed). SAM tone presentation at a preferred frequency produced a substantial increase in fluorescence over that observed in quiescent periods (respective bottom and top images in rightmost subpanels). Figure 3B displays a single-trial fluorescence trace of this same neuron during presentation of randomly-ordered SAM tones (−20 dB sound attenuation) with frequencies denoted below the trace. This record exhibits sizeable responses to low-frequency stimuli (Figure S6), allowing reliable discrimination of tuning characteristics. Upon sorting traces by increasing stimulus frequencies and averaging across multiple trials, the sharply tuned response preference of this neuron for low frequency tones is evident (Figure 3C, top row). Individual trial responses are shown in gray and the average response overlaid in black. At weaker sound levels (Figure 3C, middle and bottom rows), responses become smaller and more selectively tuned. The frequency-response area (FRA) of this neuron (Figure 3D) highlights its monotonic level dependence and preference for low frequency tones. To improve resolution, FRAs were deduced from deconvolved and thresholded signals, here and throughout (Figure S6, and Online Experimental Procedures (Two-Photon Image Analysis)). Across all active GCaMP3 neurons in our study, single events detected by deconvolution and thresholding had mean amplitudes of ~6 ± 1.5 % ΔF/FO (mean ± sd) and decay time constants ~0.8 s (Figure S7A–C). These outcomes are similar to single-spike transients in a prior study of in vivo GCaMP3 activity (Tian et al., 2009).

Figure 3. Tonal tuning of exemplar neuron residing within low-frequency pole of AI.

(A) Registration of neuron to transcranial map. Left subpanel, high- and low-frequency landmarks (H and L) obtained via transcranial imaging (scale bar, 500 μm). Box registers overall field of view for neuron-by-neuron imaging under two-photon microscopy. Middle subpanel, portion of actual field of view acquired under scanning two-photon microscopy (scale bar, 30 μm), reporting time-averaged fluorescence. Box registers individual neuron to be scrutinized in right subpanel. Right subpanel, change in fluorescence of this neuron between quiet (top) and active (bottom) periods (scale bar, 10 μm). GCaMP3 under Syn1-Cre driver line.

(B) Single-trial fluorescence as a function of time from neuron in panel A (right subpanel). Time-registered blips show frequency and timing of 30 randomly delivered SAM tones logarithmically spaced between 3 and 48 kHz.

(C) Fluorescence responses from same neuron, after sorting for tone presentation in order of increasing frequency (left to right). Each row relates to stimuli presented at different levels of sound attenuation. Results of individual trials plotted in gray and averaged responses across multiple trials in black. Strong and sharp tuning to low frequencies of 4–5 kHz.

(D) Frequency-response area (FRA) for this neuron, confirming low-frequency tuning. Intensity displays estimated spike rate, gauged by deconvolving and thresholding traces (Figure S7).

While this exemplar neuron exhibits sharp tuning to low-frequency tones, what about neighboring neurons in the same field (Figures 4A–4C)? For reference, Figure 4A again registers the location of the exemplar two-photon field to the low-frequency pole in AI, with a slightly larger fluorescence ‘scout’ image of the two-photon field shown on the bottom. The field contains 47 neurons that could be detected based on expressed GCaMP3 fluorescence, 53% of which showed fluorescence transients at any point. Of those, 80% were found to be responsive to tones, with colored circles indicating their best frequency (across all fields in this study, 835/1407 fluorescent neurons exhibited Ca2+ transients (‘active’), and 297 of these (36%) responded to tones). Figure 4B displays the frequency response characteristics of five of these neurons. The average responses to SAM tones (−20 dB attenuation) are plotted in the left column, using the same format as Figure 3C (top row). FRAs for these neurons are displayed in the right column, using identical procedures to those in Figure 3D (cell 3 is the same as in Figure 3). A first notable result is that some variability exists between neurons; thus, these signals reflect the activity of individual neurons rather than whole-field neuropil contamination (a concern with bulk-loading of chemical-fluorescent Ca2+ dyes (Kerr et al., 2005)). Second, despite modest variability, all 5 neurons clearly responded within a 1-octave low-frequency range.

Figure 4. Spatially co-localized AI neurons show sharp tuning to similar tone frequencies.

(A–C) Neuron-by-neuron responses in low-frequency AI, encompassing same field as Figure 3. GCaMP3 under Syn1-Cre.

(A) Landmarks from transcranial imaging, with registered two-photon imaging field. Same field and format as in Figure 3A, but two-photon field here encompasses modestly larger region (scale bar, 30 μm). Colored circles, best frequency of sound-responsive neurons, with color map at bottom (blue = low frequency, red = high frequency). Thicker circles delineate neurons whose responses appear in panel B.

(B) Activity of 5 neurons marked in panel A; format as in Figure 3C. Neuron 3 is same as shown in Figure 3. Sound attenuation of −20 dB was used throughout panels B and H. FRAs on right follow format in Figure 3D. FRAs scaled to 24.6 events/sec.

(C) Top subpanel, FRA averaged from all active neurons in entire field, showing considerable population tuning to low frequency stimuli. Scaled to 5.64 events/s. Middle subpanel, cumulative distribution of best-frequency spread (ΔBF, in octaves here and throughout) between all pairs of tuned neurons in field. Bottom subpanel, cumulative distribution of sharpness of tuning metric (Q factor) for all tone-responsive neurons in field, substantiating narrow frequency preference within individual neurons. Vertical dashed lines and symbols delineate mean values.

(D–F) Single-neuron responses in mid-frequency field of AI, where tone-responsive neurons demonstrate clear tuning to similar middle frequencies. Format as in A–C, but from different mouse, with −40 dB sound attenuation. GCaMP3 under Syn1-Cre. Neurons 1–4 in panel E exhibit mid-frequency tuning. Fields often contained neurons with activity not driven by tones, as illustrated by neuron 5 in panel E (white-circled neuron in panel D). Individual FRAs in panel E scaled to 7.25 events/sec, and population FRA in panel F scaled to 1.21 events/sec.

(G–I) Neuronal responses in high-frequency field of AI (or UF), where tone-responsive neurons demonstrate tuning to similar high frequencies. Format as in A–C; different mouse than in above panels. Data shown here (but not elsewhere) are from bulk-loaded Fluo-2 chemical-fluorescent dye, illustrating overall similarity to results obtained from GCaMP3. Individual FRAs in panel H scaled to 33.11 events/sec, and population FRA in panel I scaled to 4.90 events/sec.

In fact, population analysis across the entire field (all circled neurons in Figure 4A) corroborated and extended these trends, as detailed in Figure 4C. The topmost subpanel shows the average FRA for the entire field, demonstrating sharp low-frequency tuning across the population. Note the similarity to the FRA from the individual neuron shown in Figure 3D. The middle subpanel summarizes population data describing the spread in best frequencies across the field, quantified as ‘BF spread’ (ΔBF). This metric tallies the difference in best frequencies between each pair of tone-responsive neurons in the field, in octaves. Specifically, the sharp rise of the cumulative histogram for BF spread shown here, corresponding to a mean value of 0.258 octaves, substantiates that neurons across this field are highly co-tuned to a similar preferred frequency. Additionally, the bottom subpanel displays population data for the sharpness of tuning across the field, as gauged by a Q factor defined as the best frequency (BF) divided by the bandwidth of responsiveness (BW). The sharp rise of the cumulative histogram of Q, affiliated with a large mean value of 2.26, argues that neurons across the field are well tuned.

The remainder of the figure summarizes results for two-photon fields registered to middle (Figure 4D–F) and high (Figure 4G–I) frequency loci of AI in the global transcranial map. For these other regions, we also observed clustered tuning among nearby neurons, appropriately tuned to middle and high frequency tones. Further, each field had responses to a limited range of frequencies. Thus, strong co-tuning and narrow spectral preference seem characteristic across AI. Finally, the frequency preference of individual neurons in these low, middle, and high-frequency exemplar fields adheres to tonotopic organization expected from transcranial maps (e.g., see average FRAs in Figures 4C, 4F, and 4I). Further data and analysis substantiating these trends will be presented after characterization of fields in AII.

Ca2+ responses of individual neurons registered to AII

Beyond AI, our method allowed unambiguous identification of single-neuron responses in other auditory areas that have received comparatively little attention in prior two-photon Ca2+ imaging studies. In particular, we focused on AII. On the basis of multi-unit electrode recordings, neurons in AII may exhibit broad and multi-peaked tonal tuning (Stiebler et al., 1997). However, these multi-unit records leave open the possibility that the observed broad tuning actually reflects summation of sharply but heterogeneously tuned individual neurons.

Figure 5 presents the results for three two-photon fields registered to AII, displayed according to the format in Figure 4. These fields progress along the AII dorsoventral axis identified earlier in transcranial maps (Figure 2D). The low frequency pole (‘L’) is situated at the dorsal end of this axis and the high frequency pole (‘H’) at the ventral end. Results for a field registered to the ‘L’ pole are displayed in Figures 5A–5C, those for an intermediate point along the axis are shown in Figures 5D–5F, and those for the ‘H’ pole in Figures 5G–5I. These exemplar fields illustrate notable similarities and sharp contrasts in relation to AI. First, large tone-responsive Ca2+ signals could be resolved for individual neurons throughout AII, with response amplitude at least equivalent to that in AI (Figures 5B, 5E, and 5H). Second, while clearly tone responsive, many of these neurons were activated by tones spanning a remarkably broad frequency range. For example, for both neuron 3 in Figure 5B and neuron 4 in Figure 5E, strong responses were well maintained over a 2–3 octave range, something not observed in AI. This broadness of tuning is reflected in the expansive width of some of the single-neuron FRAs (right end of panels B, E, and H) and by cumulative population histograms demonstrating lower sharpness-of-tuning Q values (Figures 5C and 5F). Third, best frequencies among neighboring neurons could widely diverge, particularly as illustrated by the mid-frequency field. Here, neurons in the field collectively respond well to tones spanning the entire 5-octave test range (Figure 5E), and the cumulative histogram for BF spread is impressively right shifted (Figures 5F). Fourth, both the broad tuning of individual neurons and dispersion of best frequencies within fields collectively produced appreciable widening of whole-field average FRAs relating to all AII exemplar fields (Figures 5C, 5F, and 5I). This profile clearly contrasts with average FRAs measured in AI (Figures 4C, 4F, and 4I). Finally, despite the broad and diverse tuning of AII fields, there was some correspondence between field location and preferred frequencies. The most dorsal ‘L’ field tended to respond to low frequencies (Figure 5C, average FRA), and the most ventral ‘H’ field preferred higher frequencies (Figure 5I, average FRA). This outcome rationalizes the coarse AII tone gradient observed under transcranial mapping.

Figure 5. Broad frequency tuning and diverse best frequencies in co-localized AII neurons.

Exemplar low, middle, and high frequency AII fields, format as in Figures 4A–4C.

(A–C) Neuron-by-neuron responses in low-frequency AII field, from mouse expressing GCaMP3 under Syn1-Cre. Neurons exhibit overall preference for low frequencies (panel B), but with broad frequency responsiveness and diversity of best frequencies. Broad population FRA in panel C supports this trend. Individual and group FRAs scaled to 25 (B) and 2.62 events/sec (C). Panels B, E, and H used sound attenuation of −20 dB.

(D–F) Neuron responses in mid-frequency AII field, from another mouse expressing GCaMP3 under Syn1-Cre. Broad frequency tuning to divergent best frequencies (panel E), confirmed by population metrics (panel F). Note x-axis break for ΔBF to allow full display of larger ΔBFs. Individual and group FRAs scaled to 15.5 (E) and 2.66 events/sec (F).

(G–I) Responses in high-frequency AII field, from mouse with GCaMP3 under Emx1-Cre. Moderately sharp tuning, albeit with greater ΔBF than in corresponding high-frequency areas of AI (cf., Figure 4G–I). Individual and group FRAs scaled to 17.5 (H) and 6.09 events/sec (I).

Functional organization of AI and AII cortices revealed by multiscale optical Ca2+ imaging

The results from exemplar AI and AII fields presented thus far hint at the existence of fundamental contrasts in the functional organization of AI and AII auditory subregions. Importantly, the use of transgenic GCaMP3 mice to interrogate individual neurons registered to transcranial maps facilitated the characterization of numerous other fields, drawn from a total of 22 mice. Thirteen fields were investigated in total along the axis extending from the low-to-high frequency AI poles, as denoted in Figure 6A by squares within the translucent-cyan ovoid. Sixteen fields were studied in total along the AII low-to-high frequency axis, as marked in Figure 6D by squares within the translucent-yellow ovoid. The analysis here included all neurons whose activity increased with any tone presentation, regardless of frequency preference or tuning (see Online Experimental Procedures (Response Metrics)). This large data set fully established the trends observed above in exemplar fields. To test for a strong tonotopic axial organization in AI, we plotted best frequencies of all 154 tone-responsive neurons in these fields versus their position along a normalized axis coordinate (Figure 6B, black-filled symbols), where ‘0’ denotes the low-frequency AI pole and ‘1’ marks the dorsal high-frequency AI pole. Precise coordinates were determined by orthogonal projection onto the ventrodorsal, low-to-high-frequency axis of AI, as determined in individual mice. Additionally, the mean best frequency and coordinate position for fields were plotted on the same axis (Figure 6B, translucent squares). Both of these plots substantiate an excellent linear fit to all the two-photon data (Figure 6B, r = 0.88, p< 0.001 via Pearson’s analysis of 154 neurons), indicating that AI has a well-resolved tonotopic organization. Still, one remaining ambiguity might be that, while this relation is evident when compiled from multiple fields across the entire AI tonotopic axis (Figure 6B, black symbols), this trend is not obvious within individual fields of sizes <250 μm (as seen with our usual 40× objective). However, data-based simulations predicted that computed linear correlations would yield r values > 0.5 only if field sizes were > 300 μm (Figure S8A). Reassuringly, a linear trend was then clearly resolved within a single larger field (375 μm) imaged with a 25× objective (Figure 6B, red symbols, and Figure S8B–D; r = 0.66 and p< 0.001 via Pearson’s analysis of 30 neurons). In further support of tonotopy, cumulative histograms incorporating results from all 40× fields demonstrated limited best-frequency spread, indicative of strong co-tuning among neighboring neurons (Figure 6C, top, dashed vertical line and symbol mark the mean). Moreover, cumulative histogram analysis of Q factors corroborates sharp frequency tuning within individual neurons throughout AI (Figure 6C, bottom, dashed vertical line and symbol mark the mean). These Q values are similar to those found by microelectrode methods in rodent auditory cortex (Polley et al., 2007).

Figure 6. Contrasts in tonotopic organization of mouse AI versus AII cortex.

(A–C) Well-resolved tonotopic gradient via two-photon imaging of individual neurons within AI.

(A) Map of all two-photon imaging fields (squares in translucent ovoid) characterized along ventrodorsal tonotopic axis of AI, as resolved in transcranial maps. Each field registered onto a single canonical map (Figure S6 and Online Experimental Procedures).

(B) Best frequencies of neurons versus normalized distance along AI axis, where the ‘0’ coordinate corresponds to the low-frequency pole in AI, and the ‘1’ position marks the high-frequency landmark atop AI (i.e., UF). Each black symbol marks outcome of one neuron, and ensemble of points encompasses all tone-responsive neurons from all fields in panel A (squares). Squares in panel B plot field averages. Good linear correlation (r = 0.88, 154 neurons, p< 0.001 via Pearson’s analysis) supports strong tonotopy in AI. Normalized distance on AI axis determined by orthogonal projection onto linear axis between low- and high-frequency AI poles, determined in transcranial maps for given neurons. Fields within 300 μm of the axis included. Red symbols, data from single larger field of view, obtained with 25× objective (Figure S8B–D).

(C) Summary of co-tuning and tuning sharpness for all fields in panel A. Top, cumulative distribution of BF spread (ΔBF), as in Figure 4C. Bottom, cumulative distribution of sharpness of tuning (Q) averaged across all neurons within individual fields. Black-dashed vertical lines and symbols indicate mean values.

(D–F) Weaker tonotopic gradient in AII, same format as in panels A–C.

(D) Squares register fields residing near tonotopic axis of AII (translucent ovoid).

(E) Best frequency plotted versus normalized position along AII tonotopic axis demonstrates poorer but significant correlation (r = 0.54, 143 neurons, p< 0.001 via Pearson’s analysis).

(F) Weaker co-tuning and tuning sharpness in AII versus AI. Top, cumulative distribution of BF spread for all AII fields in panel D (black with yellow shading). Significant right shift of distribution (p< 0.042, 2-tailed Mann-Whitney, performed on metrics from 13 AI versus 16 AII fields) compared with AI distribution (fit reproduced in gray, for reference) indicates greater diversity of best frequencies at specific AII locales. Bottom, cumulative distribution of Q for all AII fields in panel D (black with yellow shading). Significant left shift of distribution (p< 0.02, 2-tailed Mann-Whitney, performed on metrics from 13 AI versus 16 AII fields) compared with AI distribution (fit reproduced in gray, for reference), showing decreased sharpness of tuning in AII. Vertical dashed lines and symbols, mean ΔBF and Q values for AII (yellow) and AI (cyan). (B–C, E–F). Data from mice expressing GCaMP3 under Syn1-Cre (n = 9) and Emx1-Cre (n = 8), and from mice bulk loaded with Fluo2 (n = 10).

In contrast, the same analysis applied to the large data set for AII indicates a substantially different profile. Contrary to prior expectations, we indeed resolve a weaker though significant tonotopic organization within AII, with adherence of BF to a tonotopic axis (Figure 6E) yielding a linear correlation with r = 0.54 (p< 0.001 via Pearson’s analysis of 143 neurons). Population statistics for ΔBF and Q in Figure 6F indicate that co-tuning and sharpness of tuning within local neuronal subpopulations in AII differ significantly from those in AI. In particular, we observe significantly decreased co-tuning of neighboring neurons compared to AI (Figure 6F, top, p< 0.042, two-sided Mann Whitney) and far broader frequency tuning within individual neurons (Figure 6F, bottom, p< 0.02, two-sided Mann Whitney). In Figure 6F, AII data are plotted in black with fits to AI data reproduced in gray for reference. To account for any potential influence of different-sized fields on the use of best-frequency spread (ΔBF) to compare co-tuning among neighboring neurons, we also normalized this metric by the distance d between pairs of neurons. This approach also furnished significantly different ΔBF/d values of 0.008 ± 0.005 octaves/μm for AI (mean ± standard deviation) versus 0.0149 ± 0.01 octaves/μm for AII (p< 0.032, two-sided Mann Whitney, performed on metrics from 13 AI versus 16 AII fields). All these population comparisons thereby substantiate that neurons in AII are not only more broadly tuned than neurons in AI, but also more disparately tuned from their neighbors (Figures 6D–6F). Though many of these features are newly recognized, the larger Q values we observe are similar to those observed by microelectrode recordings in a potentially comparable rodent ventral auditory field (Polley et al., 2007).

Overall, then, within the primary fields (AI and AAF), there is considerable agreement between the tonotopic functional organization established here by Ca2+ imaging and that resolved previously via microelectrode mapping. Notably, high- and low-frequency poles of our global transcranial map (from Figure 2B) overlay well onto a recently published microelectrode layout reproduced in Figure 7A (Guo et al., 2012). By contrast, in AII, we newly resolve a significant, though weaker, tonotopic scheme (Figures 2E and 6D–6F). Additionally, in AAF, a ventrally directed gradient (Figure 2E; and Figure 7B, red arrow), identified by tracking maximal activity with increasing tone frequencies, differs from the traditional axis shown as a dashed blue arrow in Figure 7B (Guo et al., 2012). This discrepancy may occur because the customary gradient traces the steepest rate of change in best frequency. The two definitions often yield identical axes (e.g., dorsally directed AI axis shown by green arrow in Figure 7B) but, for AAF, new organizational features may emerge.

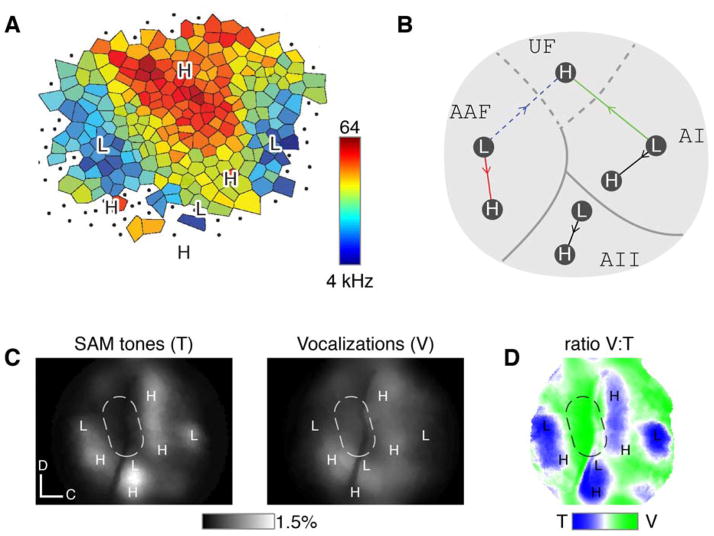

Figure 7. Tone-insensitive sector along AI/AII border.

(A) Comparison of low- and high-frequency poles of global transcranial map (from Figure 2B) to electrode-based map (Guo et al., 2012). Landmarks (L and H) translated without scaling or rotation to register low- and high-frequency loci. Ventral landmarks correspond to regions where it is difficult to assign best frequencies using electrodes (dots, indeterminate responsiveness).

(B) Features of primary fields by multi-scale imaging. Global map annotated from Figure 2F.

(C) Tone-insensitive region (dashed sector) identified by global transcranial maps from representative experiment. Left subpanel plots fluorescence response averaged across multiple SAM tone frequencies spanning entire mouse receptive range, while right subpanel plots same in response to a set of ten vocalizations (Figure 8A). Dashed oval denotes region insenstive to SAM tones. Both sets of stimuli presented at 20 dB attentuation. GCaMP3 expressed under Syn1-Cre.

(D) Ratio of vocalization to tone responses, from same mouse as in panel C. Green regions correspond to pixels favoring vocalizations (by 4:1), and blue regions to those favoring SAM tones (by 1:4). Dashed oval same as in panel C.

Responses to complex stimuli identified by multiscale approach

We next tested whether our multiscale approach could identify cortex specialized for more complex stimuli. Under transcranial imaging, we typically observed a region encompassing the border of AI and AAF that was only sparingly responsive to tones, which is visualized by taking the average fluorescence response to SAM tones over all frequencies, with tones delivered at the highest sound level tested (Figure 7C, left subpanel). The darker zone in the dashed oval is intriguing because adult mouse vocalizations (Grimsley et al., 2011) presented to this same mouse nicely elicit responses extending into the oval (Figure 7C, right subpanel). Taking the ratio of vocalization to tone responses highlights the difference (Figure 7D), as green regions correspond to pixels favoring vocalization, which overlap heavily with the region insensitive to tones (dashed oval reproduced from panel C). Blue regions denote pixels favoring tones.

Next, we investigated the response properties of single neurons within vocalization-selective regions. A set of ten mouse vocalizations were used, of which nine contained energy only in the ultrasonic range as illustrated by their spectrograms (Figure 8A). After identifying a tone-insensitive region via transcranial Ca2+ imaging (magenta oval, Figure 8B, left subpanel), we intentionally focused on a presumed high-frequency AAF region (marked by a rectangle) that corresponded to a border between vocalization-preferring (green) and tone-preferring (blue) sectors (Figure 8B, middle subpanel). The right subpanel displays the corresponding two-photon field at this location. Responses to vocalizations (Figure 8C) and SAM tones (Figure 8D) under two-photon imaging are shown for three of these neurons. The top three rows in Figure 8C illustrate single-trial fluorescence records, and the bottom row plots the average of multiple trials (dark trace, with individual trials in gray). Likewise, the top row in Figure 8D plots an individual trial, and the bottom shows the average fluorescence response to variable frequencies. Neurons 1 and 2 respond preferentially to one of ten vocalizations (the two-frequency step syllable) but are not tone-responsive. Meanwhile, neuron 3 prefers tones, consistent with a border region. Figure S8H–I summarizes statistical analysis of call selectivity. These results illustrate the power of multiscale imaging to identify stimulus-specific receptive regions and neurons.

Figure 8. Vocalization-selective neurons identified by multiscale Ca2+ imaging.

(A) Spectrograms of ten adult vocalizations, adapted from online database (Grimsley et al., 2011). Silent periods removed for clarity.

(B) Global map for this mouse identifies tone-insensitive region highlighted by magenta oval (left subpanel). High-frequency AAF region (rectangle) overlaid on color map showing ratio of vocalization to tone responses (middle subpanel). Right subpanel displays corresponding two-photon field (scale bar, 30 μm). GCaMP3 under Syn1-Cre, another mouse than in Figure 7.

(C) Single-neuron responses to vocalizations. Single trials (top three rows) illustrate responses for three neurons identified in panel B. Bottom row plots average of multiple trials (dark trace, with individual trials in gray).

(D) Single-neuron response to SAM tones, format as in panel C except only one trial is shown. No neurons in this field responded below 24 kHz, so traces are truncated.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate the enormous utility of multiscale Ca2+ imaging of transgenic GCaMP3 mice. By first monitoring activity across all auditory sensory regions to define a global map, followed by scrutiny of individual neurons registered to global coordinates, we readily resolve functional organization within auditory cortex. Indeed, a long-sought key to comprehending the coding of sensory information is just this capability—to monitor populations of neurons whose precise locations within individual brains are known (Averbeck et al., 2006).

Using this strategy in unanesthetized mice, two-photon Ca2+ measurements of individual neurons support a strongly organized tonotopic structure in the primary AI auditory cortex of mice, both at the local (<100 μm) and global scales (across AI). These results contrast with those in recent reports that used two-photon Ca2+ imaging of neurons (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2011; Rothschild et al., 2010), but do agree with and enhance the profile of prior microelectrode mapping studies (Guo et al., 2012; Hackett et al., 2011; Stiebler et al., 1997) (Figure S8 and Table 1). Though the coarse existence of some cortical tonotopic organization has never been in doubt on the scale of an entire primary auditory field, the divergence from this paradigm at smaller scales in recent two-photon studies has raised the possibility that precise tonotopy may represent an averaging ‘epiphenomenon’ of the electrode method, rather than a ‘valid description of the underlying biology’ (Guo et al., 2012). Figure S8 and Table S1 furnish head-to-head comparison among the present and prior studies. Overall, this report may unify newer two-photon imaging and traditional electrode perspectives.

Beyond the issue of tonotopicity, our multiscale approach offers new possibilities: facilitating investigation of other auditory fields, in particular to define sharply contrasting response behaviors in AII; resolving novel organizational features within AII and AAF; and readily identifying and characterizing vocalization-responsive regions and neurons.

Reconciling AI profiles from electrode-based studies and two-photon Ca2+ imaging

The differences in AI tonotopic organization observed by electrode recordings and prior two-photon Ca2+ imaging studies could arise from multiple factors. For example, single-unit electrode recordings favor the most active neurons, and multi-unit recordings convey population-averaged signals that preferentially weigh the contributions of highly active neurons. By contrast, two-photon Ca2+ imaging may encompass a sample that includes numerous weakly active neurons, whose responses could differ from those of their more active counterparts. Another sampling bias could be that two-photon studies tend to focus on superficial layers II/III of cortex that afford better optical resolution, whereas electrode studies commonly target deeper layer IV. Perhaps, highly active and tonotopically organized neurons predominate in layer IV, while weakly responding and poorly tuned neurons prevail in superficial layers II/III of cortex. A recent two-photon study argues for such a scenario via explicit comparison of responses in layers IV and II/III (Winkowski and Kanold, 2013). However, the majority of neurons investigated in the present study are from layers II/III (Figure S1Q), which nonetheless exhibit strong tonotopicity (Figures 6A–C). Moreover, microelectrode studies also confirm significant tonotopic organization in layer II/III (Guo et al., 2012). Still another form of bias relates to the possibility that two-photon Ca2+ imaging may incorporate signals of non-neuronal origin, such as from astrocytes (Kerr et al., 2005). The bulk loading of chemical fluorescent dyes used in prior Ca2+ imaging studies would robustly label astrocytes (Figure S7A–B), yielding a diffuse signal that may be difficult to exclude by simple region-of-interest analysis. GCaMP3 sensors, particularly as expressed under the neuron-selective promoter Syn1 used in many of our recordings (Figures S1 and S7A–B), are less prone to such crosstalk. A final potential concern is that parvalbumin-expressing GABAergic neurons exhibit broader tuning than excitatory neurons (Li et al., 2014). Thus, selective exclusion of GABAergic neurons (for example, ~2% express GCaMP3 under the Emx1 promoter) (Gorski et al., 2002) may bias results. However, this effect is unlikely to be significant as only ~7% of all auditory cortical neurons express parvalbumin (Yuan et al., 2011).

Beyond sampling bias, two-photon imaging could be especially vulnerable to anesthesia. As auditory cortex is several synapses removed from the cochlea, anesthesia may diminish cortical activity more severely here than in other sensory modalities (Wang, 2007). Electrodes would still detect the resulting sparse spike activity, but fluorescent Ca2+ sensors would respond poorly to isolated spikes, making it difficult to resolve response properties (Gaese and Ostwald, 2001; Kindler et al., 1999). The use of unanesthetized mice in the present study may have diminished these challenges (Figure S7E). Finally, the cortical location of neurons sampled by two-photon microscopy may have been uncertain in prior studies. Electrode mapping studies painstakingly sample the spatial extent of auditory cortex, thereby definitively establishing the location of each recording site relative to the overall cortical map. By contrast, two-photon studies often rely on stereotaxic or anatomic markers to discern the site of Ca2+ imaging. Yet, these markers vary in relation to functional maps within individual animals (Guo et al., 2012; Merzenich et al., 1973), as confirmed by our own global transcranial maps (Figures 2B–C). This variability would be especially consequential given the small size of mouse auditory cortex. Beyond suboptimal registration in primary cortex, a field assigned by stereotaxy to AI and AAF may actually reside outside these regions, for example in AII. This could lead to the appearance of weak tonotopy in primary cortex. The chance of suboptimal registration is reduced in our study by registering fields to specific coordinates in a global map.

Recent electrode studies have begun to engage these issues (Guo et al., 2012; Hackett et al., 2011), but the dissonance between electrode and Ca2+ imaging approaches has largely remained. The strong AI tonotopy observed here via two-photon imaging (Figures 6A–C) thus offers to unify perspectives from Ca2+ imaging and decades of electrode studies.

Organization of auditory cortical regions

As described in the results, multiscale imaging allows both confirmation and novel extension of tonotopic organization in primary auditory fields (AI and AAF) (Figures 7A–B). Importantly, this strategy also permits exploration of robustly registered secondary areas. New organizational features of AII are thus resolved. Many AII neurons are broadly tuned to an impressive degree (Figure 6F, bottom), as found previously using electrodes (Geissler and Ehret, 2004). Moreover, neighboring AII neurons are disparately tuned (Figure 6F, top), an insight afforded by two-photon imaging. Finally, AII has a weak but consistent dorsoventral frequency organization (Figure 6E). Altogether, these properties may reflect functions that distinguish AII from the primary fields, such as frequency-invariant, object-based representations.

Concerning more complex stimuli, multiscale imaging permitted rapid localization and interrogation of vocalization-responsive regions and neurons (Figures 7–8). This capability is timely, as the encoding of vocalizations in primate auditory cortex has become a potentially tractable realm for studying higher-order processing, where different cortical fields play complementary but as-yet-poorly-understood roles (Romanski and Averbeck, 2009). Vocalization studies in rodents (advantageous for facile transgenic manipulation) would furnish a critical counterpoint; yet, comparatively little is known, with detailed electrode studies mainly focused on AI (Carruthers et al., 2013), and the likely essential role of other subregions sparingly explored (Geissler and Ehret, 2004). In this regard, our multiscale imaging approach could prove particularly advantageous. First, global maps for each mouse allow precise registration of two-photon fields responsive to vocalization, a feature especially critical if multiple cortical subregions collaborate in sound processing. Second, responses to vocalizations can be recorded transcranially, allowing the experimenter to rapidly focus on particularly informative loci. In primates, vocalizations may even involve aspects of prefrontal cortex, in addition to the auditory fields per se (Romanski and Averbeck, 2009). Our global transcranial imaging could facilitate a search for similarly expansive involvement of cortex in mice. An exciting frontier lies ahead.

More broadly, the new information from mice may comment on auditory cortical organization across other species. In rat, similarly arranged primary fields AAF and AI are observed (Polley et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2006). Interestingly, the coarse analog of the mouse AII region would be the rat VAF secondary field, which also demonstrates a weaker tonotopic organization than AI, while nonetheless exhibiting a ventrally directed low-to-high-frequency gradient (Polley et al., 2007). Another potential commonality relates to reports in rat of a tone-insensitive region along the border of AAF and AI, similar to our murine findings (Figure 7C, ovoid)(Polley et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2006). It would then be interesting if this region of rat would also support representation of more complex stimuli. As with mice, cats also exhibit a coarsely similarly arrangement of primary AAF and AI fields, with a ventrally situated secondary AII field (Winer and Lee, 2007). It is intriguing that a multimodal AES locus resides near the junction of these three fields. Likewise, in marmosets, a pitch center resides at the juncture between primary R and AI fields (Bendor and Wang, 2005). Perhaps, there is a coarsely preserved organizational feature for representing more complex stimuli at this locus.

General applicability of the multiscale approach

The ability of two-photon Ca2+ imaging to monitor activity across hundreds of neighboring neurons is powerful. Yet, cortical organization extends beyond neuronal activity within local fields, to interacting sensory cortices that encompass larger spatial dimensions (Knopfel, 2012; Wang, 2007). Accordingly, connecting the activity of individual neurons to more global events and coordinates is crucial. For instance, for investigating cortical rearrangement during development or altered experience (Buonomano and Merzenich, 1998; de Villers-Sidani et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2012; Karmarkar and Dan, 2006), multiscale Ca2+ imaging approach could significantly expand the scope and resolution of experiments, thus far limited to electrode methods. Additionally, transcranial global imaging could simultaneously survey and register multiple cortical fields that collectively orchestrate higher-order functions (Eliades and Wang, 2008; Hubbard and Ramachandran, 2005). Indeed, several two-photon studies have already employed intrinsic imaging strategies to correspond high-resolution neuronal data to the overall layout of cortex (Andermann et al., 2011; Marshel et al., 2011; Olcese et al., 2013). Other intrinsic imaging studies have also illumined the large-scale organization of rodent auditory cortex (Bathellier et al., 2012; Kalatsky et al., 2005; Moczulska et al., 2013; Polley et al., 2007). However, such intrinsic imaging necessitates considerable multi-trial averaging, thus limiting convenience and breadth of experiments. By contrast, the multiscale imaging of GCaMP3 transgenic mice described here furnishes global maps within single trials, facilitating views of rapidly evolving plasticity and time-varying adaptation to specific stimuli (Taaseh et al., 2011), and expanding the dimensionality of stimuli and experimental complexity that can be accommodated. In the future, our imaging approaches are potentially miniaturizable, permitting readouts in awake behaving animals. As transgenic models with improved sensors arise (Chen et al., 2013), multiscale imaging should prove increasingly useful for probing the function of brain circuitry at large and small scales.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animal Surgery and General Procedures

All animal procedures approved by Johns Hopkins Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Floxed GCaMP3 mice (R26-lsl-GCaMP3, Ai38 from Jackson Labs, JAX no. 014538) (Zariwala et al., 2012) were crossed with Syn1-Cre mice (JAX no. 003966) (Zhu et al., 2001) or Emx1-Cre mice (JAX no. 005628) (Gorski et al., 2002), resulting in GCaMP3-Syn1 or GCaMP3-Emx1 mice used for experiments. Anesthesia, surgery, and imaging methods detailed in online extended experimental procedures. All imaging performed on unanesthetized mice.

Ca2+ Dye Injection and Cranial Window Preparation

In a minority of mice (e.g., Figures 4G–I), bulk-loaded Fluo-2 (TEFLabs) was used for Ca2+ imaging. For Ca2+ imaging of neurons (GCaMP3 or Fluo-2), a glass coverslip was often affixed atop craniotomy to dampen pulsations.

Wide field Transcranial Imaging of GCaMP3

We typically performed wide field imaging through a thinned skull, using 460-nm excitation focused 0–200 microns beneath dura through a 10× 0.25 NA objective (Olympus). 540-nm emission collected onto a CCD camera at 20 Hz.

Two-Photon Ca2+ Imaging

Imaging was performed with an Ultima system (Prairie Technologies). Excitation at 950 nm from a mode-locked laser was raster scanned at 5–12 Hz with emission collected in red (607/45 nm) and green (525/70 nm) channels. 40× 0.8 NA objective (Olympus) used. As noted, 25× objective (Olympus XLPlan N) was used in some instances to afford a larger field of view.

Auditory Stimulation

Microscope located in sound-attenuated room (Acoustical Solutions, Audio Seal ABSC-25) with noisy equipment placed outside. Sounds delivered by free-field speaker (Tucker-Davis Technologies, ES1) 12 cm from right ear. Ambient background noise significantly weaker than the softest stimuli presented (Figure S4G–H).

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital and perfused with freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Brains were post-fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C and stored in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C until processed. 35-μm thick coronal brain sections cut with vibratome were incubated overnight with primary antibodies against GFAP and NeuN. After rinsing, sections further incubated with secondary antibodies, rinsed, and mounted on super frost glass slides. Confocal imaging was then performed.

Data Analysis

Transcranial Ca2+ images were processed by a structured sparse encoding algorithm (Haeffele et al., 2014). For two-photon Ca2+ imaging of neurons, fluorescence signals were directly used to calculate output-versus-frequency response profiles (e.g., Figure 3C). A deconvolution method was subsequently applied to estimate spike probabilities (Vogelstein et al., 2010), used for analyzing FRAs as well as BF and Q metrics described below. For registration, transcranial maps and vascular fiduciaries were used to localize individual neurons. To compare across mice, elastic registration of each animal’s coordinates to a canonical coordinate system was performed. Best frequency (BF) was the frequency evoking strongest responses at threshold. Bandwidth was calculated as the average of the half-maximal width of Gaussian fits to output-versus-frequency plots, and the frequency range eliciting greater than half maximum responses. ‘BF spread’ (ΔBF) was defined as the absolute difference in best frequency for each pair of tone-responsive neurons in a field, measured in octaves. Q factor was the best frequency at threshold ÷ maximum bandwidth at any sound level.

Extended Methods

More complete methods appear in the online extended experimental procedures.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

High-sensitivity mode of transcranial imaging of cortex in unanesthetized mice

Spectral organization of auditory cortex under wide field imaging is highly regular

Neighboring neurons in AI are appreciably co-tuned

Increased spectral integration is observed in neurons of AII

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank M. Ben-Johny and A. Djamanakova for assistance on the manuscript, X. Wang for discussions, P.J. Adams for mouse care, X. Song for loaning 25× objective, and P. Worley for the Syn1-Cre mouse line. This work was supported by grants from the Kleberg Foundation (to D.T.Y.), NINDS (to D.T.Y.), NIH (MSTP fellowship to J.B.I.), and NIDCD (NRSA fellowship to B.H.).

References

- Andermann ML, Kerlin AM, Roumis DK, Glickfeld LL, Reid RC. Functional specialization of mouse higher visual cortical areas. Neuron. 2011;72:1025–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averbeck BB, Latham PE, Pouget A. Neural correlations, population coding and computation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:358–366. doi: 10.1038/nrn1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay S, Shamma SA, Kanold PO. Dichotomy of functional organization in the mouse auditory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:361–368. doi: 10.1038/nn.2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathellier B, Ushakova L, Rumpel S. Discrete neocortical dynamics predict behavioral categorization of sounds. Neuron. 2012;76:435–449. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendor D, Wang X. The neuronal representation of pitch in primate auditory cortex. Nature. 2005;436:1161–1165. doi: 10.1038/nature03867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonomano DV, Merzenich MM. Cortical plasticity: from synapses to maps. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1998;21:149–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers IM, Natan RG, Geffen MN. Encoding of ultrasonic vocalizations in the auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2013;109:1912–1927. doi: 10.1152/jn.00483.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, et al. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Leischner U, Rochefort NL, Nelken I, Konnerth A. Functional mapping of single spines in cortical neurons in vivo. Nature. 2011;475:501–505. doi: 10.1038/nature10193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Villers-Sidani E, Merzenich MM. Lifelong plasticity in the rat auditory cortex: basic mechanisms and role of sensory experience. Prog Brain Res. 2011;191:119–131. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53752-2.00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Villers-Sidani E, Simpson KL, Lu YF, Lin RC, Merzenich MM. Manipulating critical period closure across different sectors of the primary auditory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:957–965. doi: 10.1038/nn.2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliades SJ, Wang X. Neural substrates of vocalization feedback monitoring in primate auditory cortex. Nature. 2008;453:1102–1106. doi: 10.1038/nature06910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaese BH, Ostwald J. Anesthesia changes frequency tuning of neurons in the rat primary auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:1062–1066. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.2.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler DB, Ehret G. Auditory perception vs. recognition: representation of complex communication sounds in the mouse auditory cortical fields. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1027–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski JA, Talley T, Qiu M, Puelles L, Rubenstein JL, Jones KR. Cortical excitatory neurons and glia, but not GABAergic neurons, are produced in the Emx1-expressing lineage. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6309–6314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06309.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsley JM, Monaghan JJ, Wenstrup JJ. Development of social vocalizations in mice. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinvald A, Hildesheim R. VSDI: a new era in functional imaging of cortical dynamics. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:874–885. doi: 10.1038/nrn1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Chambers AR, Darrow KN, Hancock KE, Shinn-Cunningham BG, Polley DB. Robustness of cortical topography across fields, laminae, anesthetic states, and neurophysiological signal types. J Neurosci. 2012;32:9159–9172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0065-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett TA, Barkat TR, O’Brien BM, Hensch TK, Polley DB. Linking topography to tonotopy in the mouse auditory thalamocortical circuit. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2983–2995. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5333-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeffele BD, Young ED, Vidal R. Structured Low-Rank Matrix Factorization: Optimality, Algorithm, and Applications to Image Processing. Proceedings of The 31st International Conference on Machine Learning; Beijing, China. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Honma Y, Tsukano H, Horie M, Ohshima S, Tohmi M, Kubota Y, Takahashi K, Hishida R, Takahashi S, Shibuki K. Auditory cortical areas activated by slow frequency-modulated sounds in mice. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e68113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard EM, Ramachandran VS. Neurocognitive mechanisms of synesthesia. Neuron. 2005;48:509–520. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joachimsthaler B, Uhlmann M, Miller F, Ehret G, Kurt S. Quantitative analysis of neuronal response properties in primary and higher-order auditory cortical fields of awake house mice (Mus musculus) Eur J Neurosci. 2014;39:904–918. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. Topographic maps are fundamental to sensory processing. Brain Res Bull. 1997;44:107–112. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(97)00094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. The evolution of auditory cortex: the core areas. In: Winer JA, Schreiner CE, editors. The auditory cortex. Springer; US: 2011. pp. 407–427. [Google Scholar]

- Kalatsky VA, Polley DB, Merzenich MM, Schreiner CE, Stryker MP. Fine functional organization of auditory cortex revealed by Fourier optical imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13325–13330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505592102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmarkar UR, Dan Y. Experience-dependent plasticity in adult visual cortex. Neuron. 2006;52:577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr JN, Greenberg D, Helmchen F. Imaging input and output of neocortical networks in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14063–14068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506029102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindler CH, Eilers H, Donohoe P, Ozer S, Bickler PE. Volatile anesthetics increase intracellular calcium in cerebrocortical and hippocampal neurons. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1137–1145. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199904000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopfel T. Genetically encoded optical indicators for the analysis of neuronal circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:687–700. doi: 10.1038/nrn3293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LY, Xiong XR, Ibrahim LA, Yuan W, Tao HW, Zhang LI. Differential Receptive Field Properties of Parvalbumin and Somatostatin Inhibitory Neurons in Mouse Auditory Cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2014 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshel JH, Garrett ME, Nauhaus I, Callaway EM. Functional specialization of seven mouse visual cortical areas. Neuron. 2011;72:1040–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzenich MM, Knight PL, Roth GL. Cochleotopic organization of primary auditory cortex in the cat. Brain Res. 1973;63:343–346. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikaelian DO, Warfield D, Norris O. Genetic progressive hearing loss in the C57-b16 mouse. Relation of behavioral responses to chochlear anatomy. Acta Otolaryngol. 1974;77:327–334. doi: 10.3109/00016487409124632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moczulska KE, Tinter-Thiede J, Peter M, Ushakova L, Wernle T, Bathellier B, Rumpel S. Dynamics of dendritic spines in the mouse auditory cortex during memory formation and memory recall. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:18315–18320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312508110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohki K, Chung S, Ch’ng YH, Kara P, Reid RC. Functional imaging with cellular resolution reveals precise micro-architecture in visual cortex. Nature. 2005;433:597–603. doi: 10.1038/nature03274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcese U, Iurilli G, Medini P. Cellular and synaptic architecture of multisensory integration in the mouse neocortex. Neuron. 2013;79:579–593. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickles JO. An introduction to the physiology of hearing. United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Polley DB, Read HL, Storace DA, Merzenich MM. Multiparametric auditory receptive field organization across five cortical fields in the albino rat. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:3621–3638. doi: 10.1152/jn.01298.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanski LM, Averbeck BB. The primate cortical auditory system and neural representation of conspecific vocalizations. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:315–346. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild G, Nelken I, Mizrahi A. Functional organization and population dynamics in the mouse primary auditory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:353–360. doi: 10.1038/nn.2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiebler I, Neulist R, Fichtel I, Ehret G. The auditory cortex of the house mouse: left-right differences, tonotopic organization and quantitative analysis of frequency representation. J Comp Physiol A. 1997;181:559–571. doi: 10.1007/s003590050140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda K, Yasuda R. Principles of two-photon excitation microscopy and its applications to neuroscience. Neuron. 2006;50:823–839. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taaseh N, Yaron A, Nelken I. Stimulus-specific adaptation and deviance detection in the rat auditory cortex. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taberner AM, Liberman MC. Response properties of single auditory nerve fibers in the mouse. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:557–569. doi: 10.1152/jn.00574.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Hishida R, Kubota Y, Kudoh M, Takahashi S, Shibuki K. Transcranial fluorescence imaging of auditory cortical plasticity regulated by acoustic environments in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:1365–1376. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Hires SA, Mao T, Huber D, Chiappe ME, Chalasani SH, Petreanu L, Akerboom J, McKinney SA, Schreiter ER, et al. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat Methods. 2009;6:875–881. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein JT, Packer AM, Machado TA, Sippy T, Babadi B, Yuste R, Paninski L. Fast nonnegative deconvolution for spike train inference from population calcium imaging. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:3691–3704. doi: 10.1152/jn.01073.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Neural coding strategies in auditory cortex. Hear Res. 2007;229:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA, Lee CC. The distributed auditory cortex. Hear Res. 2007;229:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkowski DE, Kanold PO. Laminar transformation of frequency organization in auditory cortex. J Neurosci. 2013;33:1498–1508. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3101-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu GK, Li P, Tao HW, Zhang LI. Nonmonotonic synaptic excitation and imbalanced inhibition underlying cortical intensity tuning. Neuron. 2006;52:705–715. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan K, Fink KL, Winer JA, Schreiner CE. Local connection patterns of parvalbumin-positive inhibitory interneurons in rat primary auditory cortex. Hear Res. 2011;274:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zariwala HA, Borghuis BG, Hoogland TM, Madisen L, Tian L, De Zeeuw CI, Zeng H, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Chen TW. A Cre-dependent GCaMP3 reporter mouse for neuronal imaging in vivo. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3131–3141. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4469-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Romero MI, Ghosh P, Ye Z, Charnay P, Rushing EJ, Marth JD, Parada LF. Ablation of NF1 function in neurons induces abnormal development of cerebral cortex and reactive gliosis in the brain. Genes Dev. 2001;15:859–876. doi: 10.1101/gad.862101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.