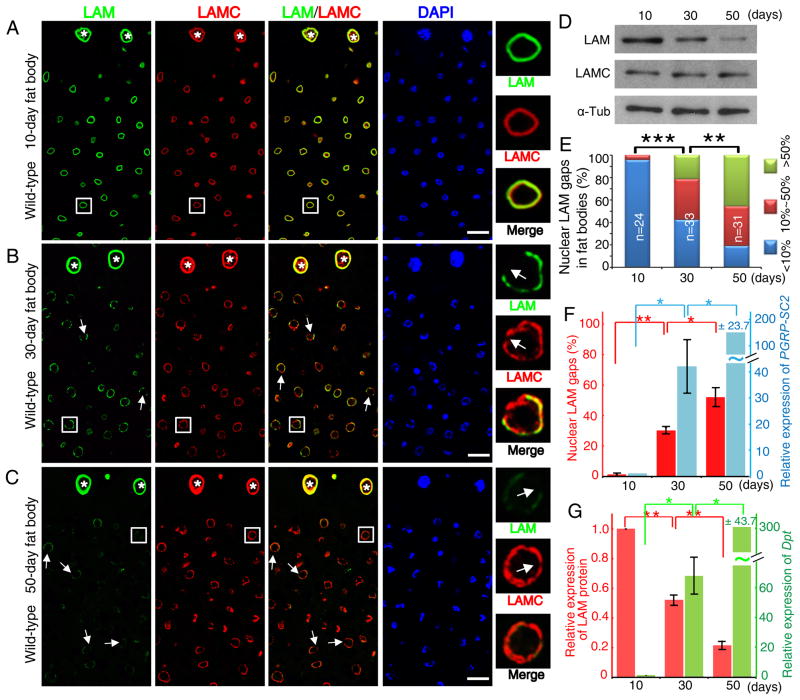

Figure 3. LAM loss in old fat body accompanies fat body inflammation.

A–C. Age-associated LAM reduction and appearance of nuclear LAM/LAMC gaps. Images (LAM, green; LAMC red; DAPI, blue) of a section of fat body next to the heart tube (see Figure 1A) from wild-type 10- (A), 30- (B), and 50-day (C) old flies. White asterisks mark the heart peripheral cells. Nuclei outlined by white squares were enlarged to the right. White arrows indicate LAM and LAMC gaps. Scale bars, 20 μm.

D. LAM and LAMC Western blotting analyses of 10-, 30-, and 50-day abdominal fat bodies. α-Tub, α-tubulin as loading control.

E. Quantification of LAM gaps. Nuclei with one or more LAM gaps were counted from confocal images from the fat body area in Figure 1A of 10-, 30-, and 50-day old flies. The percentages of nuclei with gap(s) per fat body were grouped and plotted. n, numbers of flies analyzed. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, Wilcoxon two-sample test.

F–G. The increase of nuclei with LAM gaps (F, left) or decrease of LAM protein (G, left) upon aging is accompanied by the increase of PGRP-SC2 (F, right) and Dpt (G, right) expression in fat bodies. The percentage of nuclear LAM gap was calculated by dividing the number of nuclei with one or more gaps by the total nuclei analyzed. LAM amount and PGRP-SC2, Dpt mRNAs measured from Western blots or qRT-PCR, respectively, were plotted relative to 10-day old fat bodies. Error bars, SEM, from three independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p< 0.01, Student’s t-tests.

All flies were raised in conventional condition.

See also Figure S3.