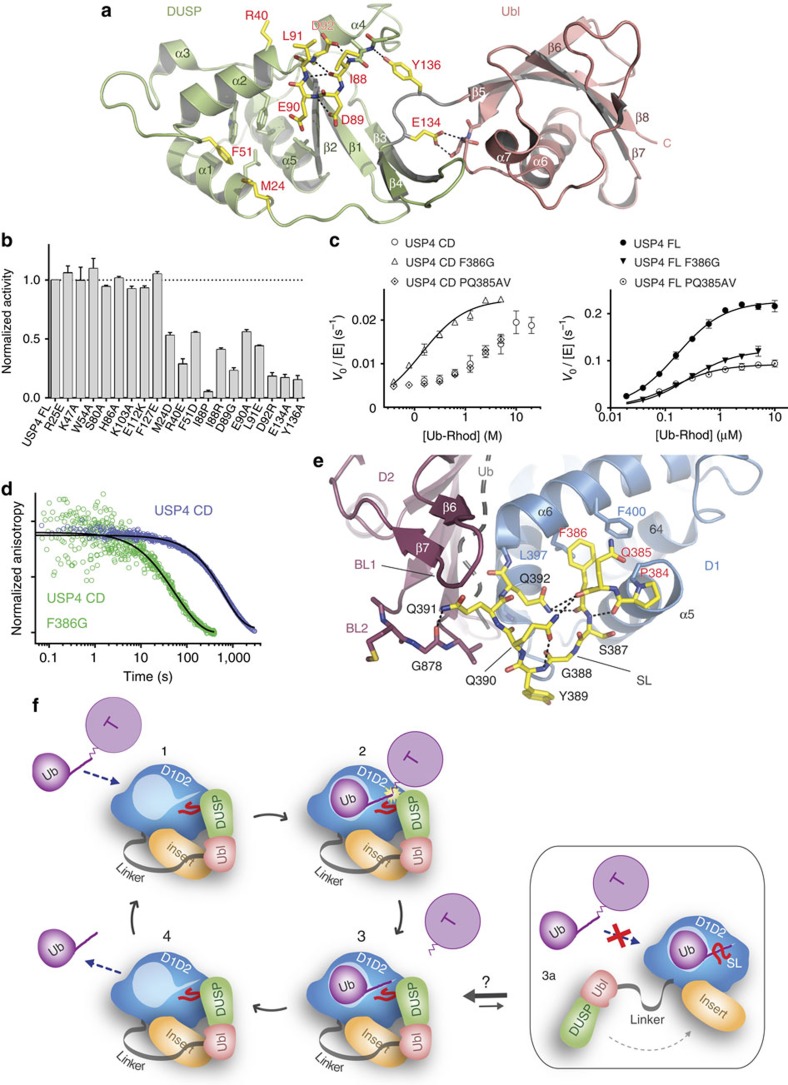

Figure 5. Single-residue mutations in the DUSP domain and in the switching loop hamper USP4 activation.

(a) Mutations mapped onto structure of the murine DUSP–Ubl domain (PDB 3JYU). Mutated residues that cause a reduction in USP4 FL activity are depicted as yellow sticks and labelled in red. Hydrogen bonds are indicated as black dotted lines. (b) Normalized activities of USP4 FL DUSP mutants measured at 5 μM Ub–Rhod concentration (error bars represent s.e.m. for at least three independent replicates). (c) Michaelis–Menten plots showing the catalytic rate of F386G and PQ385AV mutants in comparison with USP4 CD (left panel) and USP4 FL (right panel) wild type (error bars represent s.e.m. for at least three independent replicates). (d) Comparison of the normalized pre-steady-state kinetics of USP4 CD and USP4 CD F386G ubiquitin dissociation. (e) Structure of the USP4 switching loop (SL) represented as yellow sticks (the rest of USP4 is coloured as in Fig. 1b). Residues mutated in c are labelled in red. Hydrogen bonds are indicated as black dotted lines. Blocking loop 2 (BL2) is shown with stick representation. Superposed ubiquitin is represented as a grey cartoon. (f) Schematic model representing the USP4 enzymatic turnover. The ubiquitinated target (T) is recognized by USP4 (1); ubiquitin hydrolysis is catalysed by USP4 (2); the deubiquitinated target dissociates from USP4 (3); ubiquitin dissociates from USP4 allowing the access of a new substrate (4). The dissociation of the DUSP–Ubl domain from the catalytic domain allows the switching loop (SL) to retain ubiquitin in the USP4 active site, preventing the access of more substrates (3a).