Significance

Two-dimensional transition metal carbides (MXenes) offer a quite unique combination of excellent mechanical properties, hydrophilic surfaces, and metallic conductivity. In this first report (to our knowledge) on MXene composites of any kind, we show that adding polymer binders/spacers between atomically thin MXenes layers or reinforcing polymers with MXenes results in composite films that have excellent flexibility, good tensile and compressive strengths, and electrical conductivity that can be adjusted over a wide range. The volumetric capacitances of freestanding Ti3C2Tx MXene and its composite films exceed all previously published results. Owing to their mechanical strength and impressive capacitive performance, these films have the potential to be used for structural energy storage devices, electrochemical actuators, radiofrequency shielding, among other applications.

Keywords: 2D material, MXene, composite, supercapacitor, film

Abstract

MXenes, a new family of 2D materials, combine hydrophilic surfaces with metallic conductivity. Delamination of MXene produces single-layer nanosheets with thickness of about a nanometer and lateral size of the order of micrometers. The high aspect ratio of delaminated MXene renders it promising nanofiller in multifunctional polymer nanocomposites. Herein, Ti3C2Tx MXene was mixed with either a charged polydiallyldimethylammonium chloride (PDDA) or an electrically neutral polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) to produce Ti3C2Tx/polymer composites. The as-fabricated composites are flexible and have electrical conductivities as high as 2.2 × 104 S/m in the case of the Ti3C2Tx/PVA composite film and 2.4 × 105 S/m for pure Ti3C2Tx films. The tensile strength of the Ti3C2Tx/PVA composites was significantly enhanced compared with pure Ti3C2Tx or PVA films. The intercalation and confinement of the polymer between the MXene flakes not only increased flexibility but also enhanced cationic intercalation, offering an impressive volumetric capacitance of ∼530 F/cm3 for MXene/PVA-KOH composite film at 2 mV/s. To our knowledge, this study is a first, but crucial, step in exploring the potential of using MXenes in polymer-based multifunctional nanocomposites for a host of applications, such as structural components, energy storage devices, wearable electronics, electrochemical actuators, and radiofrequency shielding, to name a few.

The history of exfoliated, or delaminated, nanosheets (2D materials) dates back to the 1950s (1); however, few of the produced nanosheets are conductive. In recent years, 2D materials have been receiving increased attention, with graphene as the star material owing to its excellent electric, mechanical, and other properties (2–5). In 2011, our group reported on a new family of 2D early transition metal carbides, which combined metallic conductivity and hydrophilic surfaces (6). This novel 2D family was labeled MXenes to denote that they are produced by etching out the A layers from the layered Mn+1AXn phases (6–8) and their similarity to graphene (7).

In the Mn+1AXn, or MAX, phases, “M” is an early transition metal, “A” is a group A (mainly groups 13–16) element, “X” is carbon and/or nitrogen, and n = 1, 2, or 3 (9). So far, the MXene family includes Ti3C2, Ti2C, (Ti0.5,Nb0.5)2C, (V0.5,Cr0.5)3C2, Ti3CN, Ta4C3 (10), Nb2C, V2C (8), and Nb4C3 (11). Because there are over 70 known MAX phases (9), many more MXenes can be expected. It is important to note here that MXene surfaces are terminated by O, OH, and/or F groups from the etching process. Henceforth, these terminated MXenes will be referred to as Mn+1XnTx, where T represents terminating groups (O, OH, and/or F) and x is the number of terminating groups.

If they are not delaminated, MXenes are multilayered structures resembling those of exfoliated graphite, which have shown promising performance as electrodes in both lithium ion batteries and supercapacitors, as well as adsorbents for heavy metal ions (8, 12–16). Delamination of the multilayered materials into single- or few-layer nanosheets dramatically increases the accessible surface. Large quantities of dispersed 2D MXene flakes—delaminated Ti3C2Tx—have been produced by sonication at room temperature (7, 12, 14). The Ti3C2Tx flakes are one (single layer) to several (few layers) nanometers thick, with lateral sizes ranging from hundreds of nanometers to several micrometers.

With the exception of graphene (17–20), to date, few 2D materials have been made into highly flexible free-standing films with good electrical conductivities. Other 2D materials have been made into free-standing hybrids by the addition of conductive carbon nanotubes or graphene (21). We have previously shown that Ti3C2Tx flakes can be easily assembled into additive-free, flexible Ti3C2Tx films that show excellent electrochemical performance (14).

Ab initio simulations predict elastic moduli along the basal plane to be over 500 GPa for various MXenes (22), suggesting that they could be useful reinforcements for polymer composites. Their excellent intrinsic conductivity, in combination with their reactive and hydrophilic surfaces, also renders them attractive as fillers in a number of polymers. Furthermore, their atomic-scale thicknesses should, in principle, allow for the fabrication of nanocomposites with improved mechanical properties, which are conductive—a combination not offered by other hydrophilic additives with functionalized surfaces, such as clays (23–26), layered double hydroxides (27, 28), or graphene oxide (29–31), all of which are insulating. However, there have been no reports in the literature on MXene-based composites so far. Only a single study of MAX phase-polymer composites has been published (32). However, in that study, the MAX platelets had lateral sizes ranging from 100 to 200 nm and thicknesses of at least 4 nm.

Herein, we report, for the first time (to our knowledge), on the fabrication of conductive, flexible free-standing MXene films and polymer composite films that possess excellent flexibility, impressive electrical conductivity, and hydrophilic surfaces. In this study, Ti3AlC2 was chosen as the MAX precursor because its exfoliation and delamination have already been well developed (7, 12, 14, 33). Two polymers were chosen: poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) (PDDA) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). The former was chosen because it is a cationic polymer and the Ti3C2Tx flakes are negatively charged. The PVA was chosen for several reasons, which include its solubility in water, the large concentration of hydroxyl groups along its backbone, and its extensive utilization in gel electrolytes and composites (23, 26, 34, 35). Both Ti3C2Tx/PDDA and Ti3C2Tx/PVA composite films were fabricated and characterized. A sketch explaining the route for fabricating MXene-based films and their resulting properties is shown in Fig. 1.

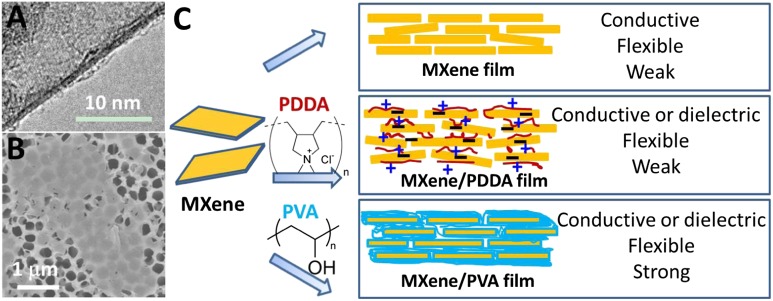

Fig. 1.

(A) TEM and (B) SEM images of MXene flakes after delamination and before film manufacturing. (C) A schematic illustration of MXene-based functional films with adjustable properties.

Results and Discussion

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) analysis of as-produced delaminated Ti3C2Tx showed primarily single (Fig. 1A) and few-layer MXene sheets (Fig. S1) with lateral sizes reaching over 2 μm (Fig. 1B). The few-layer flakes may result from restacking of the flakes during drying. These large flakes with nanoscale thicknesses are ideal for assembly into functional films and incorporation into polymer matrices.

Conductive, Flexible, Free-Standing Ti3C2Tx Films.

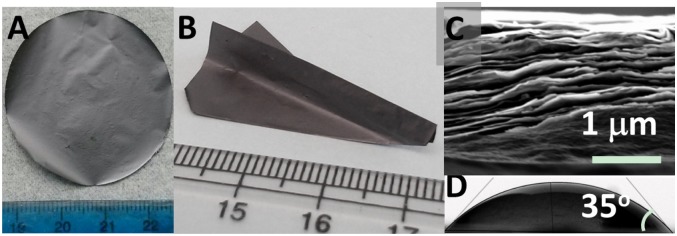

The Ti3C2Tx films were fabricated by vacuum-assisted filtration (VAF) as described in Materials and Methods. The morphologies of the as-fabricated, additive-free, free-standing Ti3C2Tx films are shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. S2. The films’ thickness can be easily tailored by controlling the MXene content in a given volume of solution. For example, a film with a thickness of ∼13 μm is shown in Fig. S2C. SEM cross-sectional images of the film reveal a well-aligned layered structure throughout the entire film (Fig. 2C and Fig. S2D). Free-standing, highly flexible films of <1 μm in thickness are also readily fabricated (Movie S1). Such thin, free-standing, conductive films built of 2D layers, which can be manufactured in aqueous environments and do not require any posttreatment but drying, are quite unique. All of the fabricated films are quite flexible and can be readily folded into various shapes without observable damage (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2 A–C).

Fig. 2.

Appearance, flexibility, and contact angle of 3-µm-thick Ti3C2Tx films. (A) Digital image of a free-standing Ti3C2Tx film with diameter of 40 mm. (B) To demonstrate the mechanical flexibility, a film was folded into the shape of a paper airplane. (C) Typical cross-sectional SEM image of a Ti3C2Tx film showing its layered structure of well-stacked Ti3C2Tx flakes. (D) Digital image of a water drop on a Ti3C2Tx film. The contact angle was measured to be 35°.

The electrical conductivities of the Ti3C2Tx films—determined by a standard four-probe technique—are of the order of 2.4 × 105 S/m, a value that is several times higher than that of graphene or carbon nanotube “paper” (36–38). Note that because the contact resistance between flakes cannot be eliminated, much higher conductivities can be expected for a Ti3C2Tx single layer. Indeed, we have shown that the conductivity of Ti3C2Tx epitaxial thin film with a nominal thickness of 28 nm is 4.3 ×105 S/m (39).

In addition to being highly conductive, the films are hydrophilic. When a water drop was placed on a Ti3C2Tx film, the contact angle was 35° (Fig. 2D), similar to cold-pressed Ti3C2 multistacked particles (6). There is thus no doubt that the Ti3C2Tx surfaces are hydrophilic. Furthermore, unlike graphene oxide (17), the assembled films did not soften, break up, or dissolve even when stored for over a month in water (Fig. S2E), and remained intact even while being shaken (Movie S2). This hydrophilicity and water stability cannot be overemphasized because it implies that—as shown herein—aqueous environments can be used throughout processing. It also augurs well for the use of MXene in applications where water is involved, such as membrane separation and desalination.

Conductive, Flexible, Free-Standing Ti3C2Tx/PDDA and Ti3C2Tx/PVA Composites.

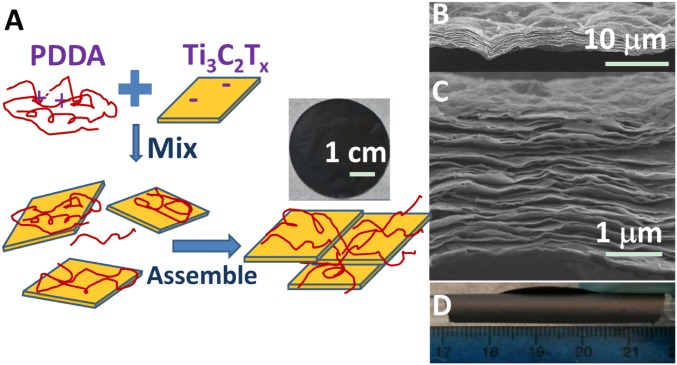

Here again, VAF was used to fabricate highly flexible Ti3C2Tx/PDDA and Ti3C2Tx/PVA films. Because the ζ-potential of the as-produced Ti3C2Tx colloidal solution was measured to be –39.5 mV, it implies that the Ti3C2Tx surfaces are negatively charged. It is for this reason that the cationic polymer, PDDA, was one of the first polymers chosen to make nanocomposites (Fig. 3A). The Ti3C2Tx/PDDA composite films assembled by VAF are composed of orderly stacked layers over the entire film (Fig. 3 B and C). A sharp peak at 4.7° can be observed in the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of these composite films, indicating the ordered stacking of Ti3C2Tx flakes along [0001] (Fig. S3A). Note that the peak shifted to a lower angle compared with that of pure Ti3C2Tx films (6.5°), which could be ascribed to the intercalation of PDDA molecules between the Ti3C2Tx flakes.

Fig. 3.

Flexible free-standing Ti3C2Tx/PDDA films. (A) Schematic illustration of synthesis of Ti3C2Tx/PDDA hybrids and their assembled films. (B and C) Cross-sectional SEM images of films at different magnifications. (D) Digital image of a film wrapped around a glass rod with a 10 mm diameter.

Here again, the film thicknesses can also be readily tailored in a range from hundreds of nanometers to tens of micrometers (Fig. S3 B and C). Similar to the pure Ti3C2Tx, films containing PDDA exhibited impressive flexibility (Fig. 3D) and a conductivity of ∼2,000 S/m. This observed decrease in conductivity compared with the pure Ti3C2Tx films is presumably due to the presence of polymer chains between the Ti3C2Tx flakes.

For reasons outlined above, PVA was the second polymer chosen. The as-fabricated Ti3C2Tx/PVA films were also free-standing and flexible (Fig. S4). The cross-section of the composites shows parallel stacking of Ti3C2Tx flakes (Fig. S5 A–C). The thicknesses of the composite films increase with increasing PVA loadings, ranging from 4 to 12 μm, for a given amount of Ti3C2Tx.

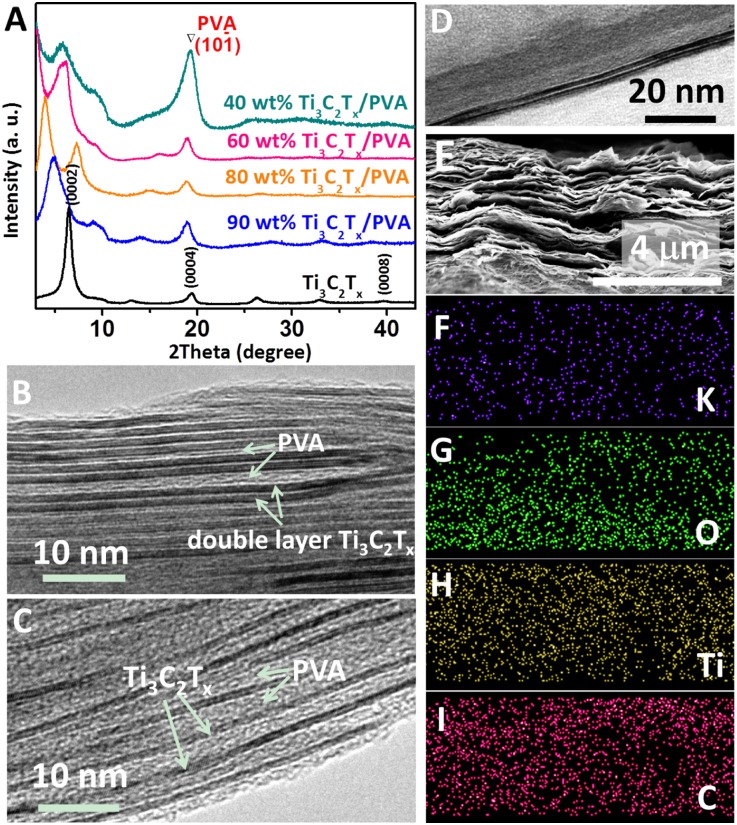

Here again, the (0002) peak shifts toward lower angles, ranging from 4.8° to 6.0° with increased PVA loadings. Concomitantly, its FWHM increases, confirming that not only do the distances between the Ti3C2Tx flakes increase, but they become less uniform as well (Fig. 4A). This is further confirmed by the high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images of Ti3C2Tx/PVA films (Fig. 4 B and C). The intercalation and confinement of PVA layers can be clearly identified in comparison with pure Ti3C2Tx flakes (Fig. 4D). Because only single-layer Ti3C2Tx is found in the composites with a high PVA content (Fig. 4C), we assume that primarily single-layer Ti3C2Tx is present in the colloidal solution after delamination. Multilayer flakes observed in pure Ti3C2Tx samples or Ti3C2Tx with lower contents of PVA (Fig. 4B) may be due to restacking of MXene layers during drying. The spacing between the layers increases with increasing amounts of PVA. This allows for conductivity control, as the film conductivity decreases with the increasing amount of PVA and separation between the Ti3C2Tx flakes (Table 1). Not surprisingly, the electrical conductivity of the composites can be tailored in a large range from 22,430 S/m to almost zero, depending on the PVA content (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Flexible free-standing Ti3C2Tx/PVA and Ti3C2Tx/PVA-KOH films. (A) XRD patterns of the Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx/PVA films. Typical HRTEM images of 90 wt% Ti3C2Tx/PVA (B) and 40 wt% Ti3C2Tx/PVA (C) films showing the intercalation of PVA between Ti3C2Tx flakes. (D) Typical HRTEM image of a double-layer Ti3C2Tx. SEM image of Ti3C2Tx/PVA-KOH film (E) and elemental maps of potassium (F), oxygen (G), titanium (H), and carbon (I) from same area.

Table 1.

Physical properties of Ti3C2Tx, Ti3C2Tx/PVA, and PVA films

| MXene content, wt% | Thickness, μm | Conductivity, S/m | Tensile strength, MPa | Young’s modulus, GPa | Strain to failure, % |

| 100 | 3.3 | 240,238 ± 3,500 | 22 ± 2 | 3.52 ± 0.01 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| 90 | 3.9 | 22,433 ± 1,400 | 30 ± 3 | 3.0 ± 0.01 | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

| 80 | 6.1 | 137 ± 3 | 25 ± 4 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.4 |

| 60 | 7.2 | 1.3 ± 0.08 | 43 ± 8 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 3.0 ± 0.5 |

| 40 | 12.0 | 0.04 ± 0.003 | 91 ± 10 | 3.7 ± 0.02 | 4.0 ± 0.5 |

| 0 | 13.0 | — | 30 ± 5 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 15 ± 6.5 |

Mechanical Properties of the Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx/PVA Films.

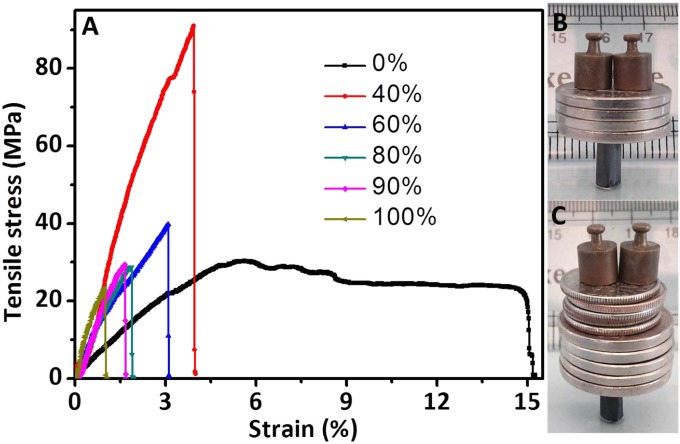

As noted above, the Ti3C2Tx films had sufficient mechanical strength for handling. The tensile strengths of a ∼3.3-μm-thick Ti3C2Tx film was 22 ± 2 MPa, with a Young’s modulus of 3.5 ± 0.01 GPa (Fig. 5A and Table 1). These values are comparable with reported graphene oxide paper and carbon nanotubes-based “bucky” paper (17, 40), but the Ti3C2Tx film has much better conductivity. By introducing 10 wt% PVA, the tensile strength was improved by 34%. The strength of Ti3C2Tx/PVA film was further improved to 91 ± 10 MPa, which was about four times larger than pure Ti3C2Tx film, by increasing the PVA loading to 60 wt% (Fig. 5A). The tensile strength of a 13-μm-thick PVA film was only 30 ± 5 MPa (Fig. 5A and Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Mechanical properties of flexible free-standing Ti3C2Tx, Ti3C2Tx/PVA, and cast PVA films. (A) Stress–strain curves for Ti3C2Tx/PVA films with different Ti3C2Tx content. (B) The 6-mm-diameter, 1-cm-high cylinder, weighing 6.18 mg, made from a 35-mm-long, 10-mm-wide and 5.1-μm-thick strip of Ti3C2Tx, can support ∼4,000 times its own weight. (C) The 6-mm-diameter, 10-mm-high hollow cylinder, weighing 4.75 mg, made from a 35-mm-long, 10-mm-wide, 3.9-µm-thick strip of 90 wt% Ti3C2Tx/PVA, can support ∼15,000 times its own weight. The loads used were nickels (5 g), dimes (2.27 g), and 2.0-g weights.

The general increase in stiffness and strength of these films indicates that at least some of the stress was transferred to the embedded Ti3C2Tx nanosheets, which in turn implies at least some interfacial bonding between the nanosheets and the PVA. The termination of the Ti3C2Tx by OH groups most probably played an important role here. In addition, the Young’s modulus of Ti3C2Tx/PVA films can be tailored by controlling the Ti3C2Tx-to-PVA ratio. A detailed study of the effects of amount of MXenes added on the mechanical and electrical properties of polymers is ongoing and will be reported in the near future.

Hollow cylinders, made by rolling Ti3C2Tx-based films with the thickness of 4–5 µm and connecting the overlapping edges by PVA, were also quite mechanically robust. For example, a hollow Ti3C2Tx cylinder, 6 mm in diameter and 10 mm high, was capable of supporting about 4,000 times its own weight (corresponding stress of ∼1.3 MPa) without visible deformation or damage. Similarly, a cylinder with the same dimensions—made of 90 wt% Ti3C2Tx/PVA—easily supported ∼15,000 times its own weight (corresponding stress of ∼2.9 MPa). These results suggest that these Ti3C2Tx-based films, with impressive conductivities, in general, have sufficient tensile and compressive strengths to be used for structural energy storage devices, similar to the ones described in ref. 5.

Capacitive Performance of Ti3C2Tx-Based Films.

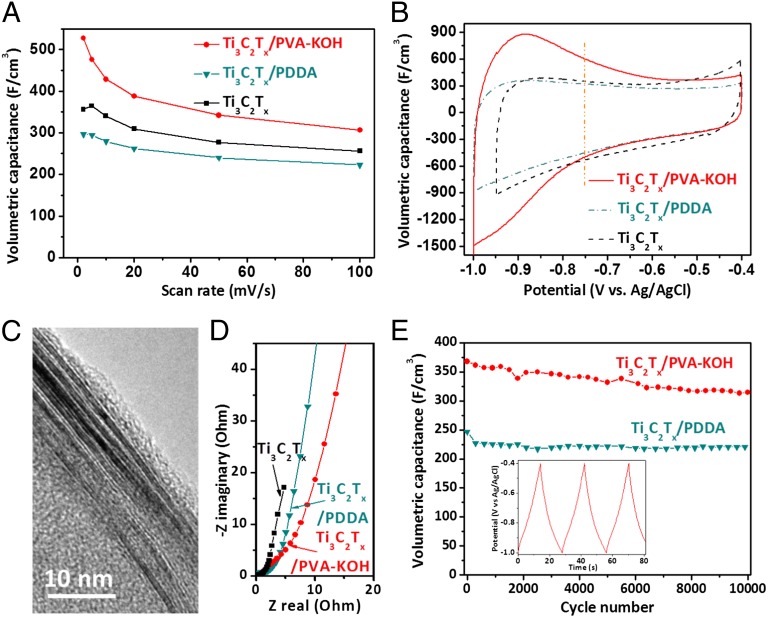

Previously, we have shown that pure Ti3C2Tx films perform quite well as additive-free electrodes in supercapacitors due to the rapid intercalation of cations between the MXene layers (14). As shown in Fig. 6A, volumetric capacitances of over 300 F/cm3 were achieved for all Ti3C2Tx-based films tested herein. These values are higher than those reported for activated graphene (60 ∼ 100 F/cm3) (41), carbide-derived carbons (180 F/cm3) (42), or graphene gel films (∼260 F/cm3) (43). The gravimetric capacitance of the PDDA-containing film was almost the same as the pure Ti3C2Tx (Fig. S6). Because of its slightly lower density (2.71 g/cm3), the resulting volumetric capacitance (296 F/cm3 at 2 mV/s) for the Ti3C2Tx/PDDA film was slightly lower than that of the pure Ti3C2Tx film (3.19 g/cm3; Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Capacitive performance of Ti3C2Tx, Ti3C2Tx/PDDA, and Ti3C2Tx/PVA-KOH films. (A) Volumetric capacitances at different scan rates. (B) CV curves obtained at a scan rate of 2 mV/s. (C) HRTEM image showing the cross-section of a Ti3C2Tx/PVA-KOH film. (D) Nyquist plots for film electrodes. (E) Cyclic stability of Ti3C2Tx/PDDA and Ti3C2Tx/PVA-KOH electrodes at a current density of 5 A/g. Inset shows last three cycles of Ti3C2Tx/PVA-KOH capacitor. All electrochemical tests were conducted in a 1 M KOH electrolyte, using three-electrode Swagelok cells with overcapacitive activated carbon and Ag/AgCl as counter and reference electrodes, respectively.

The combination of PVA and KOH is a well-established and widely used gel electrolyte for electrical energy storage devices (35, 44). Herein, we introduced KOH into the Ti3C2Tx/PVA films to endow them with multifunctionality. No visual changes were observed after the introduction of KOH (Fig. 4E). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy mapping shows a homogeneous dispersion of potassium across the Ti3C2Tx/PVA-KOH film (Fig. 4 F–I). The conductivity of this film is 11,200 S/m. The PVA between the Ti3C2Tx flakes is expected to prevent the restacking of flakes and improve ionic transport and access to MXene.

In addition, although adding PDDA to Ti3C2Tx did not greatly affect the volumetric capacitance, mixing it with PVA-KOH gel electrolyte resulted in a dramatic increase in the volumetric capacitances. The resulting capacitances were 528 F/cm3 at 2 mV/s, and over 300 F/cm3 at 100 mV/s (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, at 3.17 g/cm3, the density of a 10 wt% PVA composite was quite close to that of the pure Ti3C2Tx film (3.19 g/cm3).

Typical cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of Ti3C2Tx, Ti3C2Tx/PDDA, and Ti3C2Tx/PVA-KOH films are shown in Fig. 6B. At higher negative potentials (−0.75 to −0.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl), the behavior of all films is comparable. However, in the lower potential range (−1.0 to −0.75 V vs. Ag/AgCl—separated by a dashed orange line in Fig. 6B), the capacitances of the Ti3C2Tx/PVA-KOH films were significantly higher—at 2 mV/s—than the other two. This almost 80% enhancement in capacitance may be due to an enlarged interlayer space between MXene flakes due to the intercalation of PVA, improving access to deep trap sites (Fig. 6C). The improvement in ionic conductivity must also play a role.

Although the composite films had lower electrical conductivities measured in 4-point tests compared with the pure Ti3C2Tx film, the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) results indicate only a slight increase in resistivity for Ti3C2Tx/PDDA and Ti3C2Tx/PVA-KOH films (Fig. 6D). The latter exhibited a slight decrease in capacitance over 10,000 cycles at 5 A/g (Fig. 6E). However, at 314 F/cm3, the volumetric capacitance at the end of the 10,000 cycles was still quite respectable, indicating sufficient cyclic stability.

Conclusion

Herein, we show that Ti3C2Tx flakes by themselves, or when mixed with polymers, produce multifunctional films with attractive mechanical and electrochemical properties. Both, pure Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx/polymer composite films, with excellent conductivities, controlled thicknesses, and excellent flexibility, were fabricated. The mechanical strength of the Ti3C2Tx-based PVA composite films was much improved compared with their pure Ti3C2Tx or PVA counterparts.

When used as electrodes for supercapacitors, the composite films exhibited impressive volumetric capacitance in KOH electrolyte. Values as high as 528 F/cm3 at 2 mV/s and 306 F/cm3 at 100 mV/s were measured. The films also showed good cyclability. These values underscore the great potential of using MXenes in supercapacitor electrodes. Films with other electrolytes (e.g., ionic liquids) may widen the potential range and also produce electrodes for Li-ion batteries. From a practical point of view, our results suggest that MXenes are promising fillers in multifunctional polymer composites, which can in turn be used in such applications as flexible and wearable energy storage devices, structural components, radiofrequency shielding, water filtration, etc. Clearly, the films made here have a very useful combination of properties.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of MXene-Based Nanocomposites.

The Ti3C2Tx/PDDA composites were prepared by the dropwise addition of a PDDA solution (5 mL, 2 wt% aqueous solution) into the colloidal solution of MXene (35 mL; 0.34 mg⋅mL−1) prepared as described in SI Materials and Methods. The mixture was magnetically stirred for 24 h. The solution was again centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 1 h. The obtained sediment was washed using deionized water, and then centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for another hour. Last, the sediment was redispersed into 15 mL of deionized water, before further processing.

The MXene/PVA mixture was produced by mixing the MXene colloidal solution with a PVA (Mr, 115,000; Scientific Polymer Products) aqueous solution. Specifically, aqueous solutions of MXene (0.3 mg⋅mL−1) and PVA (0.1 wt%) were mixed, and the mixture was sonicated in a water bath for 15 min. The MXene-to-PVA weight ratios chosen were 90:10, 80:20, 60:40, and 40:60, and the resulting composite films were denoted as 90, 80, 60, and 40 wt% Ti3C2Tx/PVA, respectively. In all cases, the mass of the starting Ti3C2Tx was 13.4 ± 0.1 mg.

Fabrication of Free-Standing Ti3C2Tx and Its Composite Films.

The Ti3C2Tx and its polymer composite films were fabricated via VAF of the diluted solutions through a polypropylene separator membrane (Celgard) with a diameter of about 45 mm. A glass microfiltration apparatus, with a fritted sand supported base, was used for the vacuum filtration (Feida). The filtered cakes were air dried and detached from the filters.

Mechanical Testing.

The Ti3C2Tx-based films were cut into strips (30 mm × 3 mm) using a razor blade and glued onto supporting paper frames, which were subsequently cut after fixing the latter in the grip of a universal testing machine (KES G1 Tensile Tester). The tensile tests were performed at a loading rate of 6 mm/min; a 50-N load cell was used. All of the measurements were performed at room temperature and an average humidity of about 30%. The reported tensile strength, Young’s modulus, and strains at rupture were the averages of three to six samples.

The hollow cylinders were made by rolling strips (35 mm long and 10 mm wide) of Ti3C2Tx and 90 wt% Ti3C2Tx/PVA films around a 6-mm-diameter glass rod. The edge of the strip was glued using a very small amount of PVA solution (0.1 wt%) to hold the cylinder shape and then the rod was removed. The hollow cylinder was fixed on the top of a glass slide using PVA solution (5 wt%) before testing.

Electrochemical Testing.

All of the electrochemical tests were conducted in three-electrode Swagelok cells, using a 1 M KOH electrolyte. The produced Ti3C2Tx-based films served as working electrode, activated carbon electrodes with overcapacitance were used as counter electrode, and Ag/AgCl in 1 M KCl was used as reference electrode.

Cyclic voltammetry, galvanostatic charge–discharge, and EIS were used to test the capacitive performance using an electrochemical workstation (VMP3; Biologic). The CV scan rates ranged from 2 to 100 mV/s. The open circuit potential (OCP) was chosen as the upper limit for each cycle. The minimum potential was chosen such that to be below the electrolyte decomposition voltage. The galvanostatic charge–discharge cycles were conducted with a current density of 5 A/g, with a potential range of −1 to −0.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl. EIS was conducted at the OCP, with a 10-mV amplitude and frequencies ranging from 10 mHz to 200 kHz.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gabriel Burks, Shan Cheng, and Christopher Li for help with mechanical tests and Vadym Mochalin for the ζ-potential test. SEM, TEM, and XRD studies were performed at the Centralized Research Facilities at Drexel University. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant DMR-1310245. Z.L. and C.R. were supported by the Chinese Scholarship Council. Electrochemical work was supported as part of the Fluid Interface Reactions, Structures and Transport (FIRST) Center, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences. J.Y. was supported by Jiangsu Government Scholarship for Overseas Studies, the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, and the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University, IRT1146.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1414215111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Norrish K. The swelling of montmorillonite. Discuss Faraday Soc. 1954;18(0):120–134. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novoselov KS, et al. Two-dimensional atomic crystals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(30):10451–10453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502848102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolosi V, Chhowalla M, Kanatzidis MG, Strano MS, Coleman JN. Liquid exfoliation of layered materials. Science. 2013;340(6139):1226419–1226437. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma R, Sasaki T. Nanosheets of oxides and hydroxides: Ultimate 2D charge-bearing functional crystallites. Adv Mater. 2010;22(45):5082–5104. doi: 10.1002/adma.201001722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li N, Chen Z, Ren W, Li F, Cheng H-M. Flexible graphene-based lithium ion batteries with ultrafast charge and discharge rates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(43):17360–17365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210072109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naguib M, et al. Two-dimensional transition metal carbides. ACS Nano. 2012;6(2):1322–1331. doi: 10.1021/nn204153h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naguib M, et al. Two-dimensional nanocrystals produced by exfoliation of Ti3AlC2. Adv Mater. 2011;23(37):4248–4253. doi: 10.1002/adma.201102306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naguib M, et al. New two-dimensional niobium and vanadium carbides as promising materials for Li-ion batteries. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(43):15966–15969. doi: 10.1021/ja405735d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barsoum MW. MAX Phases: Properties of Machinable Ternary Carbides and Nitrides. Wiley; Weinheim, Germany: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naguib M, Mochalin VN, Barsoum MW, Gogotsi Y. 25th anniversary article: MXenes: A new family of two-dimensional materials. Adv Mater. 2014;26(7):992–1005. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghidiu M, et al. Synthesis and characterization of two-dimensional Nb4C3 (MXene) Chem Commun (Camb) 2014;50(67):9517–9520. doi: 10.1039/c4cc03366c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mashtalir O, et al. Intercalation and delamination of layered carbides and carbonitrides. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1716. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naguib M, et al. MXene: A promising transition metal carbide anode for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem Commun. 2012;16(1):61–64. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lukatskaya MR, et al. Cation intercalation and high volumetric capacitance of two-dimensional titanium carbide. Science. 2013;341(6153):1502–1505. doi: 10.1126/science.1241488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Come J, et al. A non-aqueous asymmetric cell with a Ti2C-based two-dimensional negative electrode. J Electrochem Soc. 2012;159(8):A1368–A1373. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng Q, et al. Unique lead adsorption behavior of activated hydroxyl group in two-dimensional titanium carbide. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(11):4113–4116. doi: 10.1021/ja500506k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dikin DA, et al. Preparation and characterization of graphene oxide paper. Nature. 2007;448(7152):457–460. doi: 10.1038/nature06016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joshi RK, et al. Precise and ultrafast molecular sieving through graphene oxide membranes. Science. 2014;343(6172):752–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1245711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H, et al. Ultrathin, molecular-sieving graphene oxide membranes for selective hydrogen separation. Science. 2013;342(6154):95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1236686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nair RR, Wu HA, Jayaram PN, Grigorieva IV, Geim AK. Unimpeded permeation of water through helium-leak-tight graphene-based membranes. Science. 2012;335(6067):442–444. doi: 10.1126/science.1211694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coleman JN, et al. Two-dimensional nanosheets produced by liquid exfoliation of layered materials. Science. 2011;331(6017):568–571. doi: 10.1126/science.1194975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurtoglu M, Naguib M, Gogotsi Y, Barsoum MW. First principles study of two-dimensional early transition metal carbides. MRS Communications. 2012;2(04):133–137. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Podsiadlo P, et al. Ultrastrong and stiff layered polymer nanocomposites. Science. 2007;318(5847):80–83. doi: 10.1126/science.1143176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walther A, et al. Large-area, lightweight and thick biomimetic composites with superior material properties via fast, economic, and green pathways. Nano Lett. 2010;10(8):2742–2748. doi: 10.1021/nl1003224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walther A, et al. Supramolecular control of stiffness and strength in lightweight high-performance nacre-mimetic paper with fire-shielding properties. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49(36):6448–6453. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Cheng Q, Lin L, Jiang L. Synergistic toughening of bioinspired poly(vinyl alcohol)-clay-nanofibrillar cellulose artificial nacre. ACS Nano. 2014;8(3):2739–2745. doi: 10.1021/nn406428n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao H-B, Fang H-Y, Tan Z-H, Wu L-H, Yu S-H. Biologically inspired, strong, transparent, and functional layered organic-inorganic hybrid films. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49(12):2140–2145. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dou Y, et al. Transparent, flexible films based on layered double hydroxide/cellulose acetate with excellent oxygen barrier property. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24(4):514–521. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Putz KW, Compton OC, Palmeri MJ, Nguyen ST, Brinson LC. High-nanofiller-content graphene oxide–polymer nanocomposites via vacuum-assisted self-assembly. Adv Funct Mater. 2010;20(19):3322–3329. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tian Y, Cao Y, Wang Y, Yang W, Feng J. Realizing ultrahigh modulus and high strength of macroscopic graphene oxide papers through crosslinking of mussel-inspired polymers. Adv Mater. 2013;25(21):2980–2983. doi: 10.1002/adma.201300118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potts JR, Dreyer DR, Bielawski CW, Ruoff RS. Graphene-based polymer nanocomposites. Polymer (Guildf) 2011;52(1):5–25. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X, et al. Ultrathin nanosheets of MAX phases with enhanced thermal and mechanical properties in polymeric compositions: Ti3Si0.75Al0.25C2. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52(16):4361–4365. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi C, et al. Structure of nanocrystalline Ti3C2 MXene using atomic pair distribution function. Phys Rev Lett. 2014;112(12):125501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.125501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu L, et al. High mechanical performance of layered graphene oxide/poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposite films. Small. 2013;9(14):2466–2472. doi: 10.1002/smll.201300819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu X, Yu M, Wang G, Tong Y, Li Y. Flexible solid-state supercapacitors: Design, fabrication and applications. Energy Environ Sci. 2014;7:2160–2181. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen H, Müller MB, Gilmore KJ, Wallace GG, Li D. Mechanically strong, electrically conductive, and biocompatible graphene paper. Adv Mater. 2008;20(18):3557–3561. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao M-Q, et al. Unstacked double-layer templated graphene for high-rate lithium-sulphur batteries. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3410. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ng SH, et al. Single wall carbon nanotube paper as anode for lithium-ion battery. Electrochim Acta. 2005;51(1):23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halim J, et al. Transparent conductive two-dimensional titanium carbide epitaxial thin films. Chem Mater. 2014;26(7):2374–2381. doi: 10.1021/cm500641a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Z, et al. Freestanding bucky paper with high strength from multi-wall carbon nanotubes. Mater Chem Phys. 2012;135(2-3):921–927. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu Y, et al. Carbon-based supercapacitors produced by activation of graphene. Science. 2011;332(6037):1537–1541. doi: 10.1126/science.1200770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heon M, et al. Continuous carbide-derived carbon films with high volumetric capacitance. Energy Environ Sci. 2011;4(1):135–138. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang X, Cheng C, Wang Y, Qiu L, Li D. Liquid-mediated dense integration of graphene materials for compact capacitive energy storage. Science. 2013;341(6145):534–537. doi: 10.1126/science.1239089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu X, et al. Stabilized TiN nanowire arrays for high-performance and flexible supercapacitors. Nano Lett. 2012;12(10):5376–5381. doi: 10.1021/nl302761z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.