Abstract

Electrospun fibers containing antiretroviral drugs have recently been investigated as a new dosage form for topical microbicides against HIV-1. However, little work has been done to evaluate the scalability of the fiber platform for pharmaceutical production of medical fabrics. Scalability and cost-effectiveness are essential criteria in developing fibers as a practical platform for use as a microbicide and for translation to clinical use. To address this critical gap in the development of fiber-based vaginal dosage forms, we assessed the scale-up potential of drug-eluting fibers delivering tenofovir (TFV), a nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor and lead compound for topical HIV-1 chemoprophylaxis. Here we describe the process of free-surface electrospinning to scale up production of TFV fibers, and evaluate key attributes of the finished products such as fiber morphology, drug crystallinity, and drug loading and release kinetics. Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) containing up to 60 wt% TFV was successfully electrospun into fibers using a nozzle-free production-scale electrospinning instrument. Actual TFV loading in fibers increased with increasing weight percent TFV in solution, and encapsulation efficiency was improved by maintaining TFV solubility and preventing drug sedimentation during batch processing. These results define important solution and processing parameters for scale-up production of TFV drug-eluting fibers by wire electrospinning, which may have significant implications for pharmaceutical manufacturing of fiber-based medical fabrics for clinical use.

Keywords: electrospinning, scale-up, microbicides, tenofovir, solid dispersions, fibers

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Women under the age of 24 years have three- to six-fold higher rates of HIV-1 infection than men in the same age category in some parts of sub-Saharan Africa[1,2]. Given the lack of an effective HIV-1 vaccine and no available options for effective female-initiated prevention, there is a need for a microbicide against HIV-1 that women can use discreetly to protect themselves from infection. Products such as vaginal rings, films, and gels are being investigated as potential dosage forms for the delivery of antiretroviral agents for the prevention of HIV-1. Pericoital dosage forms are preferred by some women, but challenges such as inadequate retention, low drug loading, and the lack of sustained release capabilities have limited their effectiveness. For example, challenges associated with low user adherence to daily gel use in some populations have been cited as a concern in the recent VOICE clinical trial[3]. Vaginal films are an alternative pericoital dosage form to gels and can be advantageous because of their compact size, ease of insertion without an applicator, and limited leakage or messiness[4,5]. However, some vaginal films exhibit relatively long dissolution times[6], and the small dosing volume combined with the low drug loadings of <~1%[7–9] may limit the effectiveness of vaginal films unless used with exceptionally potent drugs. As such, more options are needed for female-initiated protection against HIV-1 that are culturally acceptable, shelf-stable, effective, and inexpensive.

Electrospun fibers are a solid dosage form with versatility in terms of the diversity of polymers and antiviral agents that can be formulated, and they have recently been explored as a platform for vaginal drug delivery[10,11]. Fibers can be formed into multiple geometries (sheets, tubes, coatings), and conceptual dosage forms have been identified for vaginal application of fibers that are similar to vaginal films or cervical barrier devices [12]. One criteria of an ideal microbicide platform is its ability to be scaled up inexpensively, which is of particular importance for low resource settings where HIV-1 is most prevalent. Methods for scaling up the electrospinning process have already been developed and are currently being used to produce products for filtration and purification[13]. On the laboratory scale, small volumes of polymer solution are typically electrospun using a single needle electrode, syringe pump, voltage generator, and metal collector (Fig. 1). Formats used for electrospinning scale-up include multi-nozzle, centrifuge-based, and free surface, and they have been reported to increase productivity from 0.1–1 g/h (single needle electrode) to up to 6.5 kg/h (multi-nozzle)[14,15]. The NS-1WS500U (Elmarco, Inc.) is the only commercially available production-scale electrospinning instrument that uses similar technology to existing manufacturing instruments, which is important for process transferability. The instruments employ free surface electrospinning, in which a high voltage is applied across either a wire or a rotating metal drum electrode. For the wire electrode used in this work, a moving carriage deposits polymer solution onto the wire. The polymer coating undergoes a Plateau-Rayleigh instability, resulting in the formation of many charged droplets on the wire[14]. Numerous electrospinning jets emerge simultaneously from these droplets, producing a large sheet of fibers collected on a negatively charged parallel electrode. Such a system can process much larger volumes of solution than single needle electrode systems and has been reported to produce ~200 g of fibers/h, with potential for even greater productivity by combining multiple units in series[13]. Evaluating the scale-up potential is the first step in evaluating cost-effectiveness of the fiber platform, and essential to determining its practicality as a microbicide platform and translation to clinical use.

Figure 1. Electrospinning instrumentation for needle and wire electrode instruments.

Schematic (A) and photograph (C) of laboratory scale electrospinning in which a single fiber jet is electrospun from a needle/syringe pump. Schematic (B) and photograph (D) of scale-up free surface electrospinning, where numerous fiber jets are spontaneously produced from charged polymer droplets deposited on a wire electrode. A magnified inset view of the lower wire electrode is shown in (D).

In this report, we hypothesize that electrospun PVA fibers may be a good candidate for a quick-dissolving pericoital microbicide. The amorphous domains of partially hydrolyzed PVA allow for swelling and dissolution in water, and the large surface area of electrospun fibers may further promote fast dissolution and drug release. PVA has documented biocompatibility, being one of the primary components of the commercially available Vaginal Contraceptive Film (Apothecus). Tenofovir (TFV), a nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor, has been widely investigated for HIV-1 prevention. CAPRISA 004 was the first clinical trial in which a microbicide was shown to protect against HIV-1 acquisition, with a 39% overall reduction in HIV acquisition for women in the 1% TFV vaginal gel arm, and 54% reduction for women with high gel adherence[16]. TFV has also been shown to be effective when administered orally for pre-exposure prophylaxis in three clinical trials (iPrEx, Partners PrEP, TDF2)[17–19]. Given its extensive use in antiretroviral-based prevention methods, we have selected TFV to load into PVA fibers.

Here we present our work evaluating PVA fibers as a platform for vaginal drug delivery and their potential to be scaled up for mass production. We directly compare fiber morphology, drug loading, release kinetics, and crystallinity of TFV-loaded fiber meshes electrospun using a laboratory-scale needle instrument or a production-scale wire instrument. Using only water as a solvent, we encapsulated up to 60 wt% TFV (wt drug/wt fiber) into electrospun fibers without compromising fiber integrity or productivity on both needle and wire instruments. Additionally, we show the ability to electrospin solid dispersions of TFV. Surprisingly, we found that electrospun fibers containing solid dispersions of drug, even when highly crystalline, may not in fact alter release kinetics under sink conditions compared to electrospun fibers containing fully solubilized drug. Where limited solubility has previously precluded the use of some extremely hydrophobic drugs as microbicides, these results suggest that high crystallinity may not significantly impact release kinetics for electrospun fibers containing TFV. This is the first report to our knowledge of TFV fiber scale-up on a free-surface production scale electrospinning unit with direct transferability to the manufacturing scale.

1.2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

1.2.1 Solution preparation and characterization

PVA solutions were prepared by heating a proprietary blend of PVA in water (previously optimized for electrospinning on the NS-1WS500U) at 80°C until the polymer was completely dissolved. TFV (a gift from CONRAD) was added to polymer solutions at 0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, and 80 wt% TFV theoretical drug loading (defined as mass drug/mass fiber). Drug precipitate was observed in all pH-unadjusted (pH 3) TFV solutions. Given that TFV has a pKa of 4.1[20], we hypothesized that by increasing the pH, we could increase drug solubility in the polymer solutions. The pH of each of the TFV-containing solutions was adjusted from pH ~3.3 to a final pH of 7.0 using 10 M sodium hydroxide. A bench top conductivity meter (Thermo Scientific Orion Star A212), pH meter (Thermo Scientific Orion Star A111), and surface tensiometer (Kibron AquaPi ) were used to measure solution parameters in duplicate for both pH 3 and pH 7 solutions. Solution viscosity was measured using an ARG2 rheometer (TA Instruments) fitted with cone and plate geometry (1°58’48” cone angle, 40 mm diameter). A frequency sweep test was performed with a constant strain of 0.04 and ramping up angular frequency from 1–628.3 rad/s at 10 points/decade.

1.2.2 Electrospinning parameter optimization

We established electrospinning parameters for PVA solutions containing 0, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 60 wt% TFV. For small-scale electrospinning, we used a needle instrument apparatus in our lab consisting of a 30 kV voltage generator (Gamma High Voltage Research, Inc.), syringe pump (KD Scientific, Inc.), and flat metal block as a grounded collector. Parameters that were varied included flow rate (10–100 µL/min), voltage (15–20 kV), and distance to collector (9–21 cm). Observations of the formation of fiber meshes on the collector, the presence of a Taylor cone, and dripping solution were recorded for each set of parameters. One fiber mesh from 500 µL of polymer solution was electrospun for each pH 3 and pH 7 solution using the optimal electrospinning parameters (i.e., the fastest flow rate possible for which no dripping was observed). Because of our interest in comparing the properties of fibers electrospun using a large-scale instrument and with our small-scale laboratory system, we also electrospun these solutions into nanofiber meshes using a Nanospider™ NS-1WS500U large-scale production instrument (Elmarco, Inc., Czech Republic). NS-1WS500U (wire instrument) parameters were optimized by increasing the voltage until fiber strands were visible. Orifice size, carriage speed, and distance to collector were also adjusted to result in fiber production. We scaled up our production by electrospinning fiber meshes from ~20 mL of solution for each of the TFV solutions. The 10 wt% and 60 wt% TFV meshes were chosen to move forward with for fiber mesh characterizations to represent low and high drug loading.

1.2.3 Physical characterization of fiber mesh

Fiber diameter and morphology for each mesh was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Meshes were sputtered with gold/palladium for 70 s and imaged with SEM (JSM-7000F, JEOL Ltd.) with 5,000× magnification, 5–10 kV, and 10 mm working distance. Fiber size was determined using ImageJ (NIH) by measuring fibers that intersected a diagonal line drawn across each 5,000× micrograph, with n=45 fibers measured for each sample. Mass productivity was characterized by massing the amount of fibers recovered for a given volume (500 µL for small scale) or run time (30 min for large scale). Mesh thickness was measured using calipers, with n=3 measurements in random locations on the fiber mesh.

1.2.4 Drug loading and release

We evaluated actual drug loading and encapsulation efficiency by dissolving ~5–6 mg pieces of electrospun mesh in 20–40 mL citrate buffer (25 mM, pH 4.3) or phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). These conditions were chosen to simulate normal vaginal pH (~4–6) and the pH of semen (~7–8). Drug loading was calculated as mass of drug / total mass of fiber. Encapsulation efficiency was calculated as the actual amount of drug loaded in fibers / theoretical amount of drug in fiber, accounting for the mass of sodium hydroxide used to pH-adjust solutions. Drug content was measured for triplicate mesh samples using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Release kinetics were monitored at two pH values relevant to vaginal drug delivery. Citrate buffer (25 mM, pH 4.3) or PBS (150 mM, pH 7.4) were added to fiber samples to establish sink conditions (i.e., sufficient volume to be below the solubility limit of TFV), and 200 µL samples were taken at 5 min, 1h, 4h, and 24h. Drug content in release media was evaluated using HPLC methods. A Shimadzu Prominence LC20AD HPLC system and LC Solutions software was used to quantify TFV content. A Luna C18 column with 5 µm particle size and 250×4.6 mm dimensions (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) was used for analysis, run isocratically at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of a mixture of 0.045% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in HPLC grade water and 0.036% TFA in HPLC grade acetonitrile at a 72:28 ratio (v/v). TFV was detected at 259 nm with a retention time of 2.3 min. Standard solutions of TFV were prepared at 200 µg/mL in citrate buffer (25 mM, pH 4.3) or PBS and diluted to generate the calibration curves. Analysis methods were validated with standard solutions and spiked samples to ensure no interference from blank polymer fibers. Linearity was established from 1 µg/mL to 200 µg/mL in citrate buffer using a 20 µL injection volume. A separate standard curve was created for TFV in PBS for release studies conducted in PBS, with linearity from 0.5 µg/mL to 200 µg/mL.

1.2.5 Dissolution

We performed dissolution studies in sink conditions in parallel with release studies in both PBS and citrate buffer. Dissolution was monitored visually at 5 min, 1 h, 4 h, 8 h, and 24 h by rating using a qualitative scale from 0–4, with 0 being fibers completely undissolved and 4 being fibers fully dissolved. Ratings were assigned as follows: 0 = fiber mesh intact; 1= fibers wet out; 2= fiber mesh broken into large pieces; 3= fiber mesh broken into small pieces (less than a pinhead in size); 4= fiber mesh fully dissolved (no mesh visible by eye).

1.2.6 Differential scanning calorimetry

The amount of TFV in crystalline versus amorphous state was measured using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Samples were prepared by massing 6–7 mg of fibers and firmly packing fibers together before placing in aluminum pans. Pans were punctured with a needle to allow volatiles to escape prior to measurements. Temperature was ramped from 25–350°C at 10°C/min with 0.20 s/pt sampling interval under 50 mL/min nitrogen gas purge using a Q20 Differential Scanning Calorimeter (TA Instruments). TA Universal Analysis software (TA Instruments) was used to analyze data. Melting endotherms were integrated using sigmoidal tangential integration. The heat of fusion for TFV was determined by integrating the endothermic peak corresponding to the melting temperature of TFV at 283°C. Relative drug crystallinity was calculated as the heat of fusion of TFV in fibers (ΔHf) relative to the heat of fusion of TFV powder (ΔHf0), corrected for mass fraction of TFV in the sample (wdrug) determined from actual drug loading measurements (Equation 1).

| (Equation 1) |

Normalized polymer crystallinity was calculated using Equation 2, with ΔHf being the area of the melting endotherm for PVA at 193°C, ΔHf0 as the heat of fusion for 100% crystalline PVA (ΔHf0=138.6 J/g)[21], and wpolymer being the mass fraction of polymer in the sample.

| (Equation 2) |

1.2.7 X-ray Diffraction

Diffractograms for ground TFV powder, blank PVA fibers, and 60 wt% TFV fibers (pH 3 and pH 7) were obtained using a Bruker F8 Focus Powder X-ray Diffractometer. Nickel-filtered CuKα radiation was used in the 2θ range of 5–32° at 40 kV and 40 mA. SEM, DSC, and XRD were performed at the Materials Science and Engineering Department at the University of Washington.

1.2.8 Stability Studies

Drug release kinetics, drug and polymer crystallinity, and fiber morphology of four fiber formulations stored under varying temperature and humidity conditions were compared. Samples of fibers electrospun on the wire electrode instrument were stored under laboratory conditions for 12 months and compared to samples placed in an accelerated temperature/humidity chamber for an additional 30 days. Laboratory conditions refer to samples that were stored under vacuum desiccation for 6 months, heat-sealed in a plastic bag, and stored for an additional 7 months at room temperature and humidity. Accelerated conditions refer to samples stored under laboratory conditions for 12 months and then stored under high heat (40°C) and relative humidity (75% R.H.) for 30 days. We used a custom-built humidity chamber that consisted of a closed box containing a vial with saturated sodium chloride solution to establish 75% R.H. [22], and placed the chamber in an incubator to maintain 40°C. Release studies were performed in 25 mM citrate buffer as previously described. Fiber morphology and drug/polymer crystallinity were characterized using SEM and DSC, respectively, as previously described. SEM for stability studies was performed using a Sirion SEM (FEI) at the Molecular and Nanotechnology User Facility at the University of Washington, a member of the NSF National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network (NNIN).

1.2.9 Statistics

Data are displayed as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise indicated. Student’s t-tests (two-tailed with unequal variance) were performed to assess differences between encapsulation efficiency between the needle wire instruments, with statistical significance defined as p<0.05.

1.3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

1.3.1 Electrospinning parameter optimization

Using both a custom-built, small-scale laboratory system (needle electrode) and a commercial production electrospinning instrument (wire electrode), we successfully fabricated PVA fibers containing up to 60 wt% TFV. All electrospinning solutions were transferrable between the needle and wire instruments, and did not require changes to any solution properties such as conductivity, viscosity, surface tension, or pH to fabricate fibers from either platform (Table 1). PVA solutions containing TFV had measured pH values of 3.3–5.3, conductivity of 0.075–0.201 mS/cm, surface tension of 62.5–67.0 mN/m, and viscosity of 0.45–2.52 Pa*s. Viscosity increased by approximately 5-fold for the 60 wt% TFV (pH 3) solution relative to the other solutions, and was likely due to large amount of undissolved drug present in the solution at acidic pH. While it has previously been established that viscosity increases with the volume fraction of solids in solution[23], this change in viscosity was still within the range of values for productive electrospinning.

Table 1.

Electrospinning solution properties for PVA solutions containing 0, 10, or 60 wt% TFV

| pH | Volume of NaOH added (mL) b |

Conductivity (mS/cm) |

Surface Tension (mN/m) |

Viscosity (Pa*s) c |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% TFV, pH 5 | 5.31 ± 0.01 | -- | 0.075 ± 0.000 | 62.9 ± 0.4 | 0.458 ± 0.014 |

| 0% TFV, pH 7 | 6.95 ± 0.00 | 0.004 | 0.111 ± 0.000 | 67.0 ± 1.1 | 0.486 ± 0.013 |

| 10% TFV, pH 3 | 3.33 ± 0.01 | -- | 0.201 ± 0.001 | 62.5 ± 0.8 | 0.454 ± 0.006 |

| 10% TFV, pH 7 | 6.89 ± 0.02 | 0.200 | 2.230 ± 0.006 | 63.4 ± 0.3 | 0.701 ± 0.360 |

| 60% TFV, pH 3 | 3.32 ± 0.01 | -- | 0.175 ± 0.002 | 67.0 ± 5.0 | 2.515 ± 0.226 |

| 60% TFV, pH 7 | 6.94 ± 0.01 | 2.940 | 14.94 ± 0.099 | 62.3 ± 0.1 | 0.457 ± 0.008 |

Values represent average of duplicate measurements ± standard deviation.

Volume of NaOH refers to amount of 10 M NaOH necessary to adjust ~40 mL batch of polymer solution to pH ~7.

Viscosity is reported at an angular frequency of 10 rad/s.

Increasing the solution pH above the pKa of TFV enhanced drug solubility and resulted in homogenous rather than colloidal solid suspensions. However, both types of solutions showed similar surface tension and viscosity. As expected, addition of sodium hydroxide to increase pH resulted in higher solution conductivity (Table 1). For example, TFV solutions of 10 wt% and 60 wt% adjusted to pH 7 resulted in a 11-fold and 85-fold increase in solution conductivity compared to similar solutions at pH 3. The homogenous and colloidal solid suspensions were equally electrospinnable from the nozzle and wire electrodes, which allowed us to investigate the impact from electrospinning solid dispersions on the finished fibers (discussed below).

Optimized parameters for electrospinning TFV-loaded PVA fibers on both the needle and wire instruments are given in Supplementary Table 1. Because the needle and wire electrospinning systems use different electrospinning processes, it is difficult to directly correlate parameters used for each system. In the needle system, the polymer solution is mechanically forced through a needle by a syringe pump at a controlled flow rate and deposited onto a grounded metal surface. In contrast, a moving carriage is used in the free-surface system to deposit droplets of polymer solution onto a wire electrode, and fibers are pulled upward toward a parallel negatively charged wire electrode.

While this needle system produces fibers from only one Taylor cone, hundreds of Taylor cones can be simultaneously produced using the wire electrode system[14]. As expected, mass productivity greatly increased for fibers electrospun on the wire compared with the needle instrument, with 2.9–7.6 g/h produced using the wire electrode (for a single wire with length of 25 cm), and 0.04–0.14 g/h for a single needle electrode. We also observed increasing productivity with increasing drug loading, particularly for the needle instrument. This trend is likely due to the increased mass of drug in solution for electrospinning, which is not accounted for in the mass productivity calculation.

1.3.2 Physical properties of fibers electrospun using needle versus wire instruments

We observed that the needle and wire electrodes produced materials with similar mesh and fiber properties (Table 2). Fiber mesh thickness was approximately 50–220 µm and fiber diameter was approximately 200–300 nm. Fiber diameter decreased with increasing drug loading for both the needle and wire instruments, except for formulations used to fabricate 60 wt% TFV (pH 7) fibers. The wire instrument also produced fibers with slightly smaller diameters compared with the needle instrument. We attribute these differences to greater solution conductivity with increasing drug loading, and greater overall electric field strength for the wire compared to needle electrode (5.4×105 V/m and 1.6–2.2×105 V/m, respectively).

Table 2.

Physical properties of electrospun meshes on needle v. wire instruments.

| Fiber Diametera (nm) | Thicknessb (mm) | Mass Productivityc (g/h) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Needle | Wire | Needle | Wire | Needle | Wire | |

| 0% TFV, pH 5 | 301 ± 84 | 265 ± 68 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.043 | 5.54 |

| 0% TFV, pH 7 | 296 ± 87 | 243 ± 69 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.058 | 6.94 |

| 10% TFV, pH 3 | 205 ± 34 | 176 ± 55 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.067 | 5.56 |

| 10% TFV, pH 7 | 188 ± 44 | 155 ± 59 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.060 | 2.89 |

| 60% TFV, pH 3 | 184 ± 44 | 141 ± 65 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.135 | 7.64 |

| 60% TFV, pH 7 | 320 ± 70 | 242 ± 81 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.093 | 5.53 |

Fiber diameter represents average ± standard deviation (n=45 fibers).

Thickness values represent average of triplicate measurements ± standard deviation.

Mass productivity is defined as mass of final mesh divided by time to electrospin for 500 uL volume (needle) or 30 min run time (wire), with n=1. Wire length=25 cm; Wire diameter=0.2 mm.

The fiber meshes were generally white in color, soft, and flexible, with the exception of meshes of the 60 wt% TFV (pH 7) fibers, which displayed variable delamination and brittleness after storage on vacuum. That is, we observed that these fiber meshes contained separate layers that peeled apart or became stiff upon storage. Meshes with a similarly high TFV loading but fabricated without sodium hydroxide did not exhibit delamination or brittleness. Therefore, we expect that these physical properties are not due to high drug content but are a result of base catalyzed hydrolysis of the acetyl groups on the PVA polymer, which result in hydroxyls that can participate in interchain hydrogen bonding. Further studies are needed to quantify the actual mechanical changes in fibers resulting from pH adjustment and storage conditions.

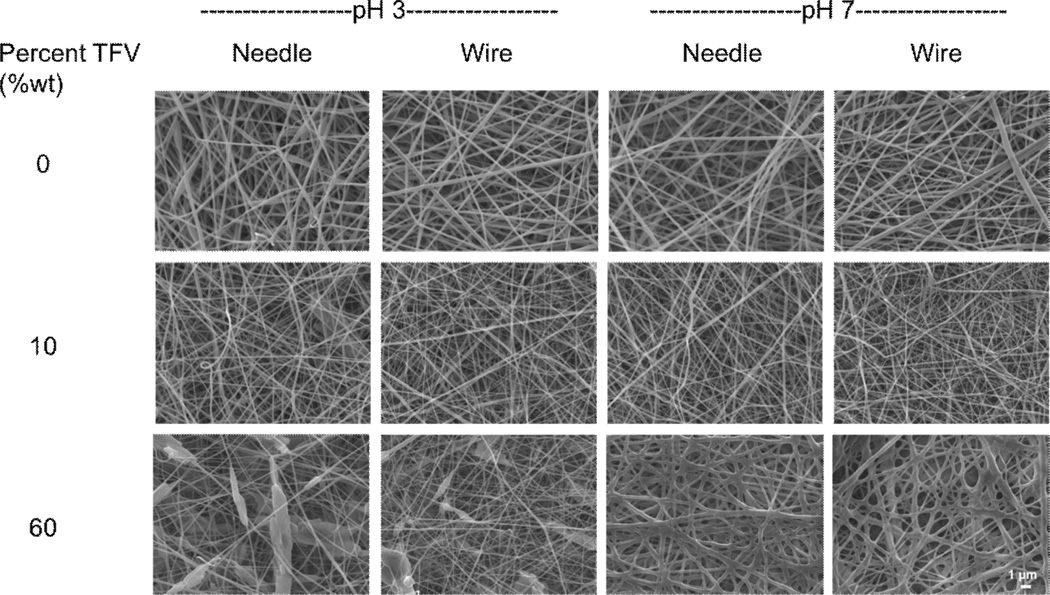

Electrospinning solid dispersions of TFV resulted in fibers with visible solid deposits that we attribute to TFV drug crystals. SEM images of fibers electrospun on the needle and wire instrument show that the finished fibers have a generally smooth and cylindrical morphology (Fig. 2). Of particular note, the 60 wt% TFV formulations that were pH-adjusted with base (pH 7) produced fibers with fused morphology and diameters that were 100–130 nm larger than fibers formulated from pH-unadjusted solutions (pH 3). This observation was similar on both the needle wire instruments. The larger diameter may be caused by addition of sodium hydroxide and increased hydroxy content of the PVA polymer, which can participate in inter- and intra-chain hydrogen bonding that results in decreased chain flexibility during electrospinning. Taken together, these results indicate that physical properties of TFV fabrics based on PVA are consistent between fibers electrospun using laboratory scale needle-based electrospinning and production scale wire electrode electrospinning.

Figure 2. Fiber morphology is consistent between needle and wire electrospinning for fibers containing up to 60 wt% TFV.

SEM images of PVA fibers containing 0, 10, or 60 wt% TFV from needle instrument (laboratory scale) and wire instrument (manufacturing scale). Images of both unadjusted (pH 3) and pH 7 fibers are displayed. Scale bar = 1 µm.

1.3.3 Drug loading is consistent between needle and wire electrospinning

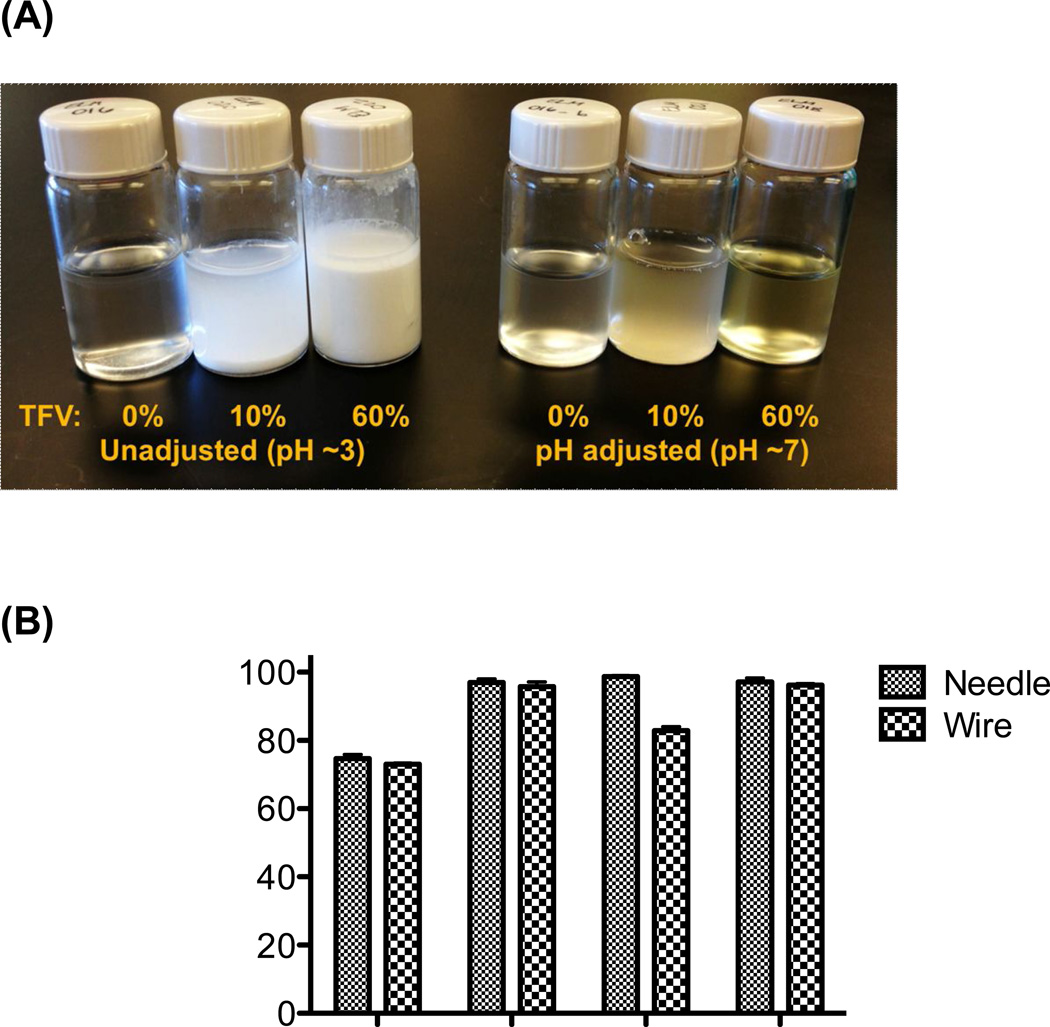

Encapsulation efficiency, drug loading, and drug crystallinity were compared between meshes with 10 wt% and 60 wt% TFV drug loading to understand the influence of drug content on the electrospinning process and resulting materials. We found that actual drug loading and encapsulation efficiency of TFV was comparable between needle and wire electrospinning. Actual TFV loading was found to increase with increasing TFV content in solution (Table 3). As expected, encapsulation efficiency was improved from ~75–80% to nearly 100% when solution pH was adjusted to maintain TFV solubility compared with electrospinning solid dispersions of TFV (Fig. 3). The only significant difference observed between actual drug loading and encapsulation efficiency values for needle versus wire electrospinning was for the 60 wt% TFV (pH 3) fibers, in which the fibers produced with the wire instrument had a ~10% decrease in absolute actual drug loading compared with the fibers produced with the needle instrument. We attribute this difference to the settling of drug precipitate in the carriage tube during electrospinning with the wire instrument, leading to a lower actual drug encapsulation. This problem may be overcome by more uniformly micronizing the drug prior to electrospinning or by actively mixing the polymer solution in the reservoir during electrospinning.

Table 3.

Actual drug loading and crystallinity of fibers electrospun from needle or wire electrodes.

| Actual Drug Loadinga (wt%) | Relative drug crystallinityb (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Needle | Wire | Needle | Wire | |

| 0% TFV, pH 5 | 0 | 0 | nd | nd |

| 0% TFV, pH 7 | 0 | 0 | nd | nd |

| 10% TFV, pH 3 | 7.5 | 7.3 | nd | nd |

| 10% TFV, pH 7 | 9.4 | 9.4 | nd | nd |

| 60% TFV, pH 3 | 59.2 | 49.7 | 96.1 | 96.3 |

| 60% TFV, pH 7 | 52.4 | 51.9 | nd | 2.0 |

Actual drug loading represents average measured by dissolving meshes in citrate buffer (n=3).

Relative drug crystallinity was calculated from differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) thermograms and is reported as percentage of crystalline TFV in fibers relative to the heat of fusion of TFV drug in powder form, correcting for mass fraction of drug in sample. Nd=not detected.

Figure 3. Electrospinning solid suspensions of TFV results in reduced encapsulation efficiency.

(A) The solubility of TFV in polymer solutions is visibly improved by using sodium hydroxide to raise solution pH. (B) The increased solubility of TFV in solution translates to an increased encapsulation efficiency of TFV in PVA nanofibers, measured by analyzing drug content in dissolved fibers with HPLC.

Interestingly, fibers were able to incorporate a remarkably high drug loading of up to 60% of TFV by mass. We also attempted to electrospin a PVA solution containing 80% TFV (pH adjusted to 7) on the wire instrument, but no fiber formation was observed. Therefore, we expect the upper limit of drug loading to be between 60–80 wt% TFV in this fiber formulation using the wire instrument. Antiretroviral-containing vaginal films in development have been reported to have drug loadings of 0.04 – 1.4% (w/w)[7–9]. Thus, the nanofiber platform appears to offer potential for much higher drug loadings than can be obtained with published film formulations. Achieving high drug loading is advantageous in that it allows for drugs with a wider range of potency to be delivered in addition to minimizing the mass of final product that must be administered. For example, to deliver a 40 mg dose of TFV that is consistent with what was used in the CAPRISA 004 trial[16], a fiber mesh ranging from 67–400 mg would need to be administered for 60 wt% and 10 wt% loaded fibers, respectively. While vaginal films in development have been dosed at comparable masses of 90–400 mg [7,9,24], to achieve an equivalent dose of 40 mg of TFV at the currently published drug loading of ~1.4% (w/w) would necessitate a vaginal film mass of ~3,000 mg.

1.3.4 Drug and polymer crystallinity

Relative drug crystallinity was found to be similar for fibers electrospun from the wire compared to the needle electrode (Fig. 4, Table 3). The DSC thermograph we obtained for TFV is consistent with previously observed results[25] that shows a broad peak near 100°C indicative of release of water from monohydrate form of TFV, recrystallization of drug at 210°C, melting at approximately 280°C, and exothermic degradation above 300°C. For 60 wt% TFV fibers (pH 3) electrospun using both the needle and wire electrode, a large melting endotherm was observed near 290°C that correlates to a 96% relative drug crystallinity. In contrast, for 60 wt% TFV fibers (pH 7), this peak was absent and indicated that only a small amount of loaded TFV (0–2%) is in the crystalline form relative to TFV drug powder. A small second peak was observed near ~270°C for this sample only that we attribute to an alternate drug crystal packing conformation. The high relative drug crystallinity in 60 wt% TFV (pH 3) samples is expected because of the presence of solid dispersions of TFV drug in pH-unadjusted (pH 3) solutions and resulting fibers, as confirmed by SEM micrographs. Upon increasing the solution pH to 7, TFV was completely solubilized and resulted in homogenous electrospinning solutions. No peaks were detected for 10% TFV solutions (either pH 3 or pH 7). Results from DSC were consistent with XRD data on the same samples, indicating that a greater amount of crystalline TFV is present in 60 wt% TFV fibers that contain solid dispersions (pH 3) compared to 60 wt% TFV fibers (pH 7) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 4. Increasing TFV solubility prior to electrospinning reduces the final crystalline drug content in fiber meshes.

Representative DSC thermograms of TFV-containing fibers and controls (TFV drug standard and blank PVA fibers) are displayed here. While a large peak indicative of crystalline drug is present for unadjusted 60 wt% TFV fibers, fibers made from pH-adjusted 60 wt% TFV solutions do not have this peak. Vertical lines indicate the melting temperatures of PVA (193°C) and TFV (283°C) standards.

The melting temperature of the PVA polymer was found to be 193°C and is evident in all fiber samples, except for 60 wt% TFV (pH 7) samples, which had no peaks near this temperature. TFV-containing fiber samples resulted in a 4–8°C decrease in the polymer melting temperature relative to pure PVA powder or blank PVA fibers, likely due to drug molecules disrupting the hydrogen bonding between PVA chains (Supplementary Table 2). Similar additive-induced melting temperature depression has been observed previously and attributed to disruption of the crystal structure [26–28]. Blank PVA fibers and PVA powder had similar nominal values of polymer crystallinity of approximately 29%. There was minimal change in polymer crystallinity for 10% TFV fibers samples compared to blank PVA fibers. In contrast, normalized polymer crystallinity was reduced to ~22% for fibers with 60 wt% TFV loading (pH 3). No Tm peak was detected for PVA in the 60 wt% TFV (pH 7) samples. Since this peak was absent for only the 60 wt% TFV (pH 7) fibers, we expect that the high volume of sodium hydroxide needed to pH-adjust these solutions influenced the final polymer crystal structure and also affected the bulk physical properties of these fibers. Overall, there is a trend for decreasing PVA crystallinity with increasing TFV loading. In addition, these results suggest that both polymer and drug crystallinity in fibers is similar for needle and wire electrospinning systems, and that solid dispersions of drug result in increased drug crystallinity in the final fibers.

1.3.5 Quick fiber dissolution and burst release of TFV from electrospun meshes

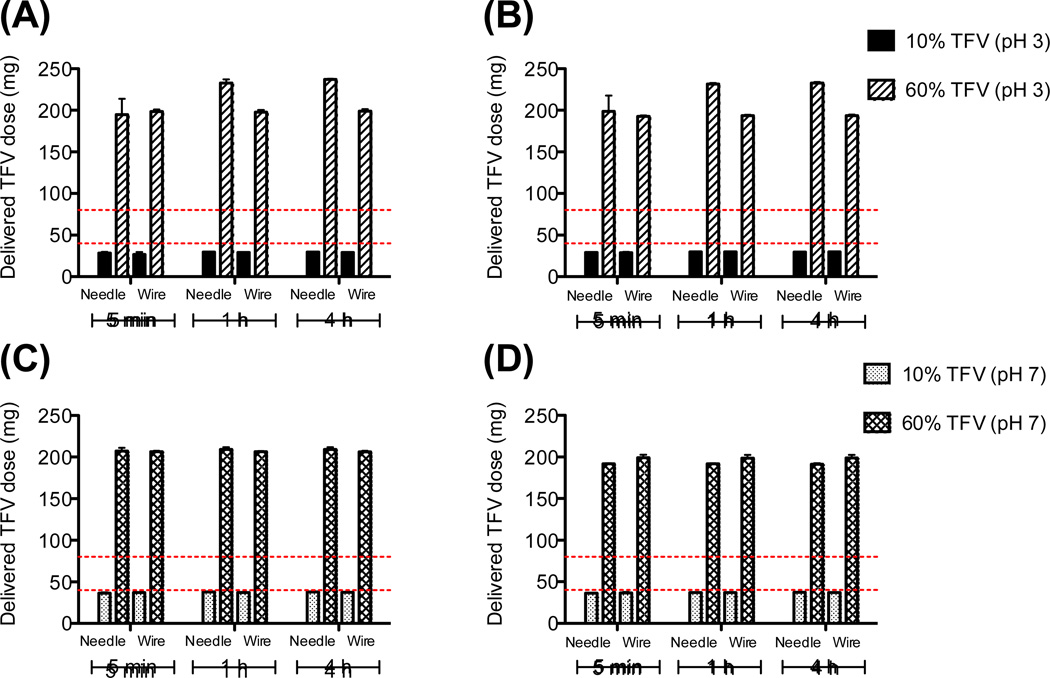

Burst release of >95% TFV from fibers was observed within 5 min for nearly all formulations under sink conditions in both PBS (pH 7.4) and citrate buffer (pH 4.3) (Fig. 5). Release kinetics were consistent between the small scale needle instrument and large scale wire instrument. While reduced drug crystallinity has previously been associated with faster release[29,30], we observed only a small impact of TFV crystallinity on the release rate. Burst release occurred for all fiber formulations regardless of their crystallinity, with a slightly prolonged release of about 85% of total contents within 5 min for needle-based 60 wt% TFV fibers (pH 3). We hypothesize that the electrospinning process constrained the size of crystals that were incorporated into final fiber meshes to a threshold below which differences in crystalline state have an indistinguishable impact on release rate.

Figure 5. Burst release of TFV within 5 min at pH 4.3 and 7.4 is similar for meshes electrospun using both needle and wire instruments.

Graphs display cumulative release of TFV in pH 4.3 citrate buffer (A, C) or pH 7.4 PBS (B, D) for fibers spun on needle versus wire instruments. Release from fibers incorporating solid dispersions of TFV (solution unadjusted at pH 3) are displayed in (A) and (B), and release from fibers from solutions adjusted to pH 7 are shown in (C) and (D). The y axis shows delivered dose TFV per 400 mg fiber mesh, with red lines indicating the recommended range for daily vaginal application (40–80 mg). 100% release corresponds to ~40 mg delivered dose for 10% TFV fibers and ~240 mg delivered dose for 60 wt% TFV fibers.

All TFV-containing fibers were qualitatively observed to dissolve completely within 1 h in both PBS and citrate buffer, with most samples dissolving in 5 min or less (Supplementary Table 3). Notably, drug-containing fibers dissolved more quickly than blank fibers in citrate buffer (pH 4.3), possibly due to the more intact polymer crystalline structure present within blank fibers. Because of the quick fiber dissolution and the hydrophilic nature of both PVA and TFV, monophasic burst release was expected from these polymeric fibers. Such a release profile may be beneficial for pericoital microbicides in which it is desirable to have having high concentrations of drug that is immediately bioavailable (i.e., drug that is dissolved and able to be taken up by cells, as opposed to locked in solid dispersions). These studies were performed under sink conditions to better understand the material properties of the nanofiber delivery system. Further release and dissolution studies evaluating drug release kinetics and fiber dissolution in low volumes of fluid will be important to better understand translation of these systems for intravaginal drug delivery.

1.3.6 Stability Studies

We found that the actual drug content did not change for fiber samples stored under both laboratory and accelerated storage conditions (Supplementary Fig. 2). Additionally, the storage conditions tested did not affect release kinetics for PVA fibers containing 10 and 60 wt% TFV for both unadjusted and pH-adjusted fibers, with all fiber formulations releasing >95% of total drug content within 1 h.

Storage conditions had little effect on polymer melting temperature, polymer crystallinity, or TFV crystallinity for fiber samples stored under laboratory or accelerated conditions, except for 60 wt% TFV (pH 7) fibers (Fig. 6). For this sample, we observed a large peak near ~160°C for the 13 mo. room temp/humidity condition only, suggesting a change in polymer crystallinity. Relative drug crystallinity for 60 wt% TFV (pH 7) fiber samples corresponding to the peak at 293°C remained at <2% of the total TFV content, despite differing storage conditions (Supplementary Table 4). A second peak around ~270°C observed only for the 60 wt% TFV (pH 7) fiber samples increased in size upon long-term storage, corresponding to an increase in relative drug crystallinity of 18% (freshly electrospun) to 35% (both laboratory and accelerated conditions). The increase in crystallinity in this sample did not result in a change in drug release kinetics, supporting our hypothesis that electrospun fibers may constrain crystal size below a threshold where changes in crystallinity do not significantly impact drug release.

Figure 6. Drug and polymer crystallinity are minimally impacted by storage conditions.

DSC thermograms indicate minimal effect of storage condition on polymer or drug crystallinity, with the exception of fibers containing 60 wt% TFV (pH 7). Conditions include original electrospun fibers (<1 month storage at room temperature and humidity), fibers stored for 13 months under laboratory conditions (room temperature and humidity), and samples stored for 12 months under laboratory conditions and an additional 30 days at 40°C / 75% R.H.

Morphology of fiber meshes remained similar for fibers stored under laboratory conditions compared with fibers stored at accelerated temperature and humidity (Supplementary Fig. 3). Fiber diameter increased for both storage conditions compared with freshly electrospun meshes, but this change did not impact drug release kinetics. We also observed an increase in fusing of 60 wt% TFV (pH 7) meshes for both storage conditions compared to the freshly electrospun mesh.

The minimal changes we observed in crystallinity, drug loading, release, and morphological properties of TFV-PVA fiber meshes suggest that they are stable over 12 months under laboratory conditions and for at least 30 days at high humidity and temperature. The accelerated condition of this study may be limited in that 75% R.H. may not have been maintained throughout the entire period due to water absorption by the PVA fibers. Future studies will need to accommodate water absorption by the fibers to maintain constant humidity.

1.4 CONCLUSION

In this work, we established parameters for electrospinning PVA solutions containing 0–60 wt% TFV into fibers. We successfully transferred materials used to electrospin TFV-PVA fibers from a laboratory scale system to a production scale system, demonstrating that both systems can be used to produce fibers with similar morphologies, drug loading, and release kinetics. Additionally, we found that while solid dispersions of TFV can be successfully electrospun into fibers at loadings of up to 60 wt% by mass, fibers containing fully solubilized TFV had enhanced encapsulation into fibers and reduced drug crystallinity. Degree of crystallinity was not found to impact release rate under sink conditions for these formulations. However, high drug crystallinity may affect biodistribution by reducing drug solubility, in addition to influencing the mechanical properties and uniformity of fiber meshes.

Physical characterization of fiber meshes including mechanical testing of fibers, evaluating the transition into “gel-like” material in low volumes of fluid, and post-dissolution studies to assess osmolarity, pH, and rheology of hydrated fibers will be critical for moving a microbicide formulation forward[4]. These characterizations have not been performed for these TFV-PVA formulations, as the focus of this work was to evaluate the potential for manufacturing scale-up of drug-loaded fibers. Future work will investigate properties such as pH, osmolarity, and rheology of electrospun fibers post-dissolution in physiologically relevant conditions.

Overall, given the comparability of needle and wire electrospinning instruments in terms of fiber morphology, drug loading, encapsulation efficiency, and release kinetics, these results support the potential for scale-up of TFV-loaded fibers. The transferability of electrospun fibers to manufacturing scale justifies continued investigation of fibers for use as topical microbicides.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research was supported by a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1067729) and the National Institutes of Health (AI09864801) to KAW. EK was supported by a NSF graduate research fellowship. Assistance with solution property characterization and XRD was provided by R. Edmark, and assistance with stability studies was provided by C. Nhan. We thank R. Edmark and S.F. Chou for critical discussions and review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- DSC

differential scanning calorimetry

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PVA

poly(vinyl alcohol)

- R.H.

relative humidity

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

- TFV

tenofovir

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- XRD

x-ray diffraction

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gengiah TN, Abdool Karim Q. Implementing microbicides in low-income countries. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glynn JR, Caraël M, Auvert B, Kahindo M, Chege J, et al. Why do young women have a much higher prevalence of HIV than young men? A study in Kisumu, Kenya and Ndola, Zambia. AIDS Lond Engl. 2001;15(Suppl 4):S51–S60. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Microbicide Trials Network. Daily HIV Prevention Approaches Didn’t Work for African Women in the VOICE Study. Atlanta: 2013. [Accessed 13 March 2013]. Available: http://www.mtnstopshiv.org/node/4877. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garg S, Goldman D, Krumme M, Rohan LC, Smoot S, et al. Advances in development, scale-up and manufacturing of microbicide gels, films, and tablets. Antiviral Res. 2010;88:S19–S29. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nel AM, Mitchnick LB, Risha P, Muungo LTM, Norick PM. Acceptability of Vaginal Film, Soft-Gel Capsule, and Tablet as Potential Microbicide Delivery Methods Among African Women. J Womens Health. 2011;20:1207–1214. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CAMI Multipurpose Prevention Technologies for Reproductive Health: 2011 Think Tank. Washington, D.C.: 2011. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akil A, Parniak M, Dezzutti C, Moncla B, Cost M, et al. Development and characterization of a vaginal film containing dapivirine, a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), for prevention of HIV-1 sexual transmission. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2011;1:209–222. doi: 10.1007/s13346-011-0022-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sassi AB, Cost MR, Cole AL, Cole AM, Patton DL, et al. Formulation Development of Retrocyclin 1 Analog RC-101 as an Anti-HIV Vaginal Microbicide Product. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2282–2289. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01190-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ham AS, Rohan LC, Boczar A, Yang L, W Buckheit K, et al. Vaginal Film Drug Delivery of the Pyrimidinedione IQP-0528 for the Prevention of HIV Infection. Pharm Res. 2012;29:1897–1907. doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0715-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang C, Soenen SJ, van Gulck E, Vanham G, Rejman J, et al. Electrospun cellulose acetate phthalate fibers for semen induced anti-HIV vaginal drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2012;33:962–969. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ball C, Krogstad E, Chaowanachan T, Woodrow KA. Drug-Eluting Fibers for HIV-1 Inhibition and Contraception. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e49792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blakney AK, Ball C, Krogstad EA, Woodrow KA. Electrospun fibers for vaginal anti-HIV drug delivery. Antiviral Res. 2013;100(Supplement):S9–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Persano L, Camposeo A, Tekmen C, Pisignano D. Industrial Upscaling of Electrospinning and Applications of Polymer Nanofibers: A Review. Macromol Mater Eng. 2013;298:504–520. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forward KM, Rutledge GC. Free surface electrospinning from a wire electrode. Chem Eng J. 2012;183:492–503. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo CJ, Stoyanov SD, Stride E, Pelan E, Edirisinghe M. Electrospinning versus fibre production methods: from specifics to technological convergence. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:4708. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35083a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karim Q, Karim SSA, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Tenofovir Gel, an Antiretroviral Microbicide, for the Prevention of HIV Infection in Women. Science. 2010;329:1168. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, et al. Preexposure Chemoprophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Men Who Have Sex with Men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, et al. Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Heterosexual Men and Women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, et al. Antiretroviral Preexposure Prophylaxis for Heterosexual HIV Transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:423–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costa AP, Xu X, Burgess DJ. Freeze-Anneal-Thaw Cycling of Unilamellar Liposomes: Effect on Encapsulation Efficiency. Pharm Res. 2013:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-1135-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peppas NA, Merrill EW. Differential scanning calorimetry of crystallized PVA hydrogels. J Appl Polym Sci. 1976;20:1457–1465. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenspan L. Humidity fixed points of binary saturated aqueous solutions. J Res Natl Bur Stand. 1977:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeffrey DJ, Acrivos A. The rheological properties of suspensions of rigid particles. AIChE J. 1976;22:417–432. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobaria N, Badhan A, Mashru R. A Novel Itraconazole Bioadhesive Film for Vaginal Delivery: Design, Optimization, and Physicodynamic Characterization. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2009;10:951–959. doi: 10.1208/s12249-009-9288-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson TJ, Gupta KM, Fabian J, Albright TH, Kiser PF. Segmented polyurethane intravaginal rings for the sustained combined delivery of antiretroviral agents dapivirine and tenofovir. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2010;39:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Craig DQ. The mechanisms of drug release from solid dispersions in water-soluble polymers. Int J Pharm. 2002;231:131–144. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00891-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guirguis OW. Thermal and structural studies of poly (vinyl alcohol) and hydroxypropyl cellulose blends. Nat Sci. 2012;04:57–67. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ago M, Okajima K, Jakes JE, Park S, Rojas OJ. Lignin-Based Electrospun Nanofibers Reinforced with Cellulose Nanocrystals. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:918–926. doi: 10.1021/bm201828g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verreck G, Chun I, Peeters J, Rosenblatt J, Brewster ME. Preparation and Characterization of Nanofibers Containing Amorphous Drug Dispersions Generated by Electrostatic Spinning. Pharm Res. 2003;20:810–817. doi: 10.1023/a:1023450006281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu D-G, Branford-White C, White K, Li X-L, Zhu L-M. Dissolution Improvement of Electrospun Nanofiber-Based Solid Dispersions for Acetaminophen. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2010;11:809–817. doi: 10.1208/s12249-010-9438-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.