Abstract

Isonitriles are delicately poised chemical entities capable of being coaxed to react as nucleophiles or electrophiles. Directing this tunable reactivity with metal and non-metal catalysts provides rapid access to a large array of complex nitrogenous structures ideally functionalized for medicinal applications. Isonitrile insertion into transition metal complexes has featured in numerous synthetic and mechanistic studies, leading to rapid deployment of isonitriles in numerous catalytic processes, including multicomponent reactions (MCR). Covering the literature from 1990–2014, the present review collates reaction types to highlight reactivity trends and allow catalyst comparison.

Keywords: catalysis, condensation, coupling, isocyanides, isonitriles

1 Introduction

Driven largely by an emphasis on multicomponent reactions,[1] the rich chemistry of isonitriles[2] is experiencing a renaissance.[3] The synthesis of isonitriles has blossomed because isonitriles provide a rapid entry into drug-like molecules, heterocycles,[4] and diverse molecular scaffolds.[5]

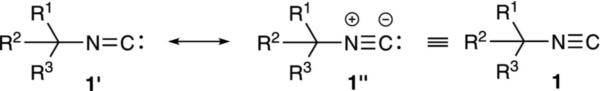

Isonitriles have a highly unusual structure. The isonitrile carbon bears a free electron-pair and is one of the few, naturally occurring stable carbenes.[6] Crystal-lographic analyses indicate that the isonitrile group is linear and not bent, suggesting structure 1″ as a better representation than implied by 1′ where the sp2 N would suggest a trigonal structure (Figure 1). Infrared spectra are consistent with the isonitrile carbon–nitrogen unit having triple bond character. The IR resonance at ~2100 cm–1 is only slightly less than those of the corresponding nitrile at ~2200 cm–1. For simplicity, isonitriles are often drawn as in 1 with a triple bond but no charges.

Figure 1.

Isonitrile representations.

The formal divalent character of isonitriles places them as carbene equivalents capable of sequentially adding a nucleophile and an electrophile. The carbon is weakly nucleophilic, and requires a potent electrophile partner such as the iminium ions that are intermediates in the Ugi reaction.[7] Dramatic progress in Ugi, Passerini, and related multicomponent additions has recently been reviewed.[1–3]

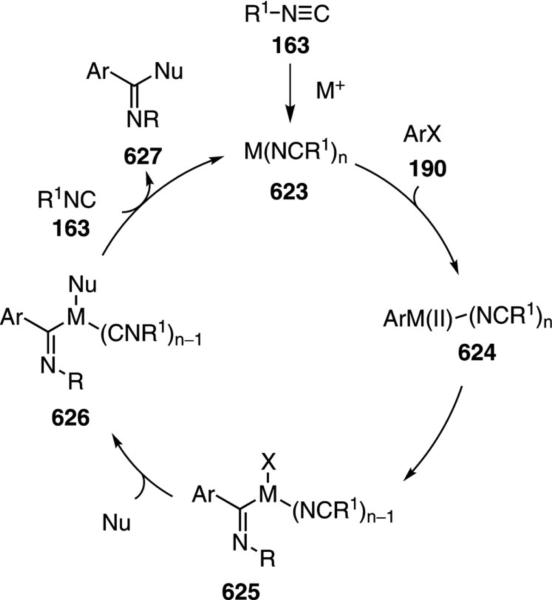

Isonitriles are emerging as key coupling partners in transition metal-catalyzed insertion reactions. Isonitriles readily associate with transition metals because of a strong s-donation from the lone pair on carbon with a simultaneous back donation into the excellent p*-acceptor orbitals of the NC unit.[7] Compared with their isoelectronic CO counterparts, isonitriles are stronger σ-donors which results in particularly strong complexes with metals in high oxidation states.[8] Conversely, the π-acceptor properties are weaker than those of CO resulting in poorer complexation to metals in low oxidation states.

A measure of the excellent ligating properties of isonitriles is gleaned from the ability of CNCH2CO2Me to displace a tridentate pybox ligand from a palladium complex.[9] A similar ligand displacement with a pincer complex causes catalyst deactivation in one case and in another, modification of the catalyst through insertion, to form the true precatalyst.[10] Strong complexation of isonitriles through σ-donation and π-acceptance is exploited in hexakis(2-methoxyisobutylisonitrile)-99mTc(I), a radiotracer used for myocardial perfusion imaging.[11]

The excellent ligation of isonitriles to transition metals has been exploited to remove spent ruthenium from cross-metathesis reactions.[12] In many cases, metal coordination to isonitriles facilitates either internal or external nucleophilic attack to form carbene-ligated metal complexes.[13]

Catalytic turnover with isonitriles is challenging because of the strong coordination to transition metals. Metal coordination activates isonitriles toward nucleophilic attack and simultaneously retards dissociation. In some cases, adding the isonitrile slowly over the course of the reaction sufficiently retards isonitrile complexation to make catalysis viable.

Unlike catalytic cycles involving the insertion of CO, the analogous insertion of isoelectronic isonitriles is significantly less common. The challenge in catalyzing insertion reactions with isonitriles lies in preventing multiple insertions leading to polymers, and preventing irreversible complexation to the catalyst. Many catalytic cycles access medium-sized metallocycle intermediates in which an intramolecular reaction or reductive elimination is faster than further isonitrile insertion.

The most frequently used catalysts are palladium complexes. Several palladium complexes are capable of catalyzing reactions with isonitriles without ligand exchange or isonitrile insertion into the ligand.[14] Many reactions proceed through palladium(II) species, formed through oxidative addition, that react with isonitriles through an insertion into a palladium carbon bond. In several instances discrete palladium(II) complexes have been demonstrated to react with isonitriles through an insertion mechanism to provide characterized intermediates.[14] Subsequent reductive elimination sequences close the catalytic cycle.

Facile coordination of isonitriles to metals increases the acidity of the adjacent protons. Deprotonation of metal-complexed isonitriles often proceeds with weak bases such as triethylamine.[15] Metallation affords nucleophiles that can react in stepwise alkylations and in concerted [3+2]cycloaddition with alkenes and alkynes.

This review surveys catalytic insertions of isonitriles into carbon-metal bonds and reactions catalyzed by activation of the isonitrile moiety. Although some catalysts function as Lewis acids, catalysts are only included if the isonitrile is activated rather than the electrophile. The catalysis therefore differs from Ugi and Passerini reactions where Lewis acid catalysts bind to the electrophile. Particularly interesting are several organic catalysts that activate isonitriles through hydrogen bonding. Only reactions with synthetically useful yields are included. An increased focus on isonitrile-activated reactions is loosely traced to 1990 which represents the earliest date of the articles included in the review.

The review is organized according to the product generated through the isonitrile condensation. In some cases the first-formed product is employed as an intermediate en route to a different target material, often a heterocycle. The categorization of catalytic methods by product type allows a direct comparison between different catalysts and catalytic cycles that is expected to facilitate future method development.

2 Aldol-Type Condensations

Lewis acidic metals activate isonitriles toward deprotonation. The resulting nucleophiles react with imines and aldehydes to form aldol-type intermediates, which typically react further by attacking the isonitrile function. Isocyanoacetates are easily deprotonated in the absence of a Lewis acid catalyst and often the background non-catalyzed condensation occurs at a similar rate. Overall the condensation provides a route to oxazolines and imidazolines.

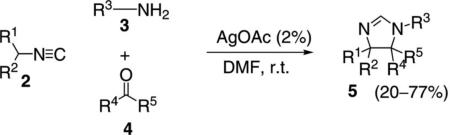

During the multicomponent condensation of α-acidic isocyanides with ketones and primary amines, the formation of 2H-2-imidazolines was catalyzed by AgOAc [Eq. (1)].[16,17] Substituted isocyanoacetates 2

|

(1) |

(R1=CO2R6) form 2-imidazolines 5 readily in DMF, but the conversion is incomplete in other solvents unless AgOAc is added. Isocyanoamides are similarly activated by AgOAc or CuI.

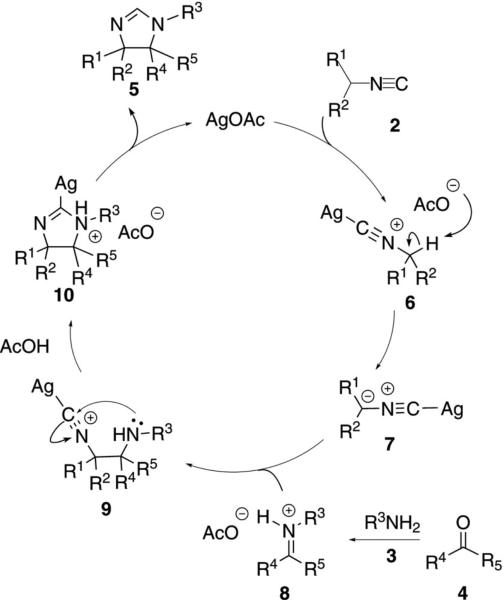

AgOAc activates isonitrile 2 toward deprotonation by complexing to the isonitrile carbon (Scheme 1). Deprotonation of the silver-isonitrile complex 6 by acetate yields the nucleophile 7. Nucleophilic attack of 7 on iminium 8 affords 9, possibly through an anti transition structure to minimize steric demand, which sets the trans stereochemistry in the imidazoline. Subsequent intramolecular attack by the amine onto the isonitrile affords argentate 10. Proton transfer, formally within 10, yields 2-imidazoline 5 and regenerates the catalyst.

Scheme 1.

Silver-catalyzed imidazoline synthesis.

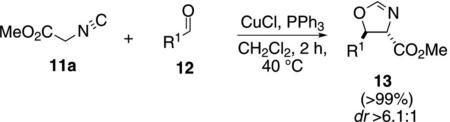

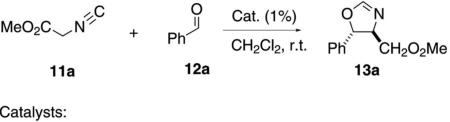

CuCl and PPh3 catalyze the condensation of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) with aldehydes 12 [Eq. (2)].[18] The mechanism of this aldol-type condensation, like

|

(2) |

most similar condensations, directly follows Scheme 1 with aldehyde 12 substituting for the iminium 8. All the reactions were quantitative and exhibited a high preference for the trans-oxazoline 13.

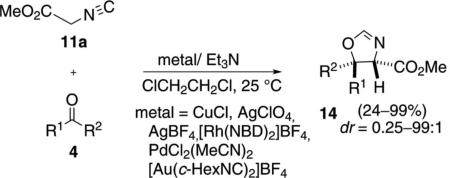

Methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) was condensed with a series of ketones 4 to afford substituted oxazolines 14 [Eq. (3)]. Extensive base and catalyst screening

|

(3) |

identified AgClO4, AgBF4, CuCl, and AgOAc as competent catalysts.[19] Methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) is easily enolized and the uncatalyzed aldol condensation is particularly favorable in polar solvents.[20] The condensation with electron-deficient ketones work well. Unactivated ketones such as acetophenone require heating to 50°C for 24 h. Aliphatic ketones fail to react completely, affording oxazolines 14 with yields less than 37%. Typically the trans-oxazoline 14 is the major diastereomer.[21]

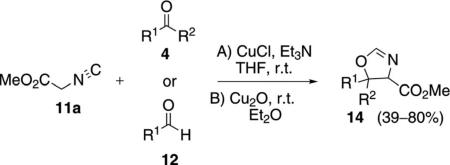

A series of oxazolines 14 was prepared by condensing methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) with aldehydes 12 or ketones 4 [Eq. (4)].[22] The copper(I) salts CuCl and

|

(4) |

Cu2O, were found to be more efficient than either t-BuOK or ZnCl2, providing a direct comparison of catalytic and non-catalytic methods.

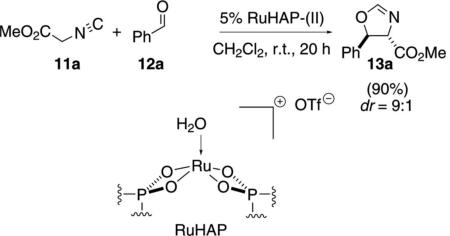

A hydroxyapatite-bound cationic ruthenium complex catalyzes the condensation of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) with benzaldehyde (12a) [Eq. (5)].[23]

|

(5) |

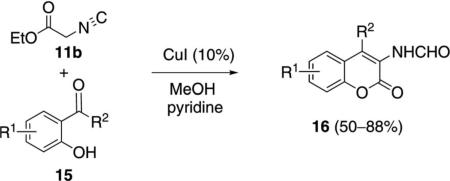

Copper iodide catalyzes the condensation of ethyl isocyanoacetate (11b) with ortho-hydroxyphenyl ketones 15 [Eq. (6)]. Methanol is the optimal solvent because the aminocoumarins 16 are insoluble and can

|

(6) |

be isolated simply by filtration. The condensation is interesting in affording lactones rather than oxazolines.

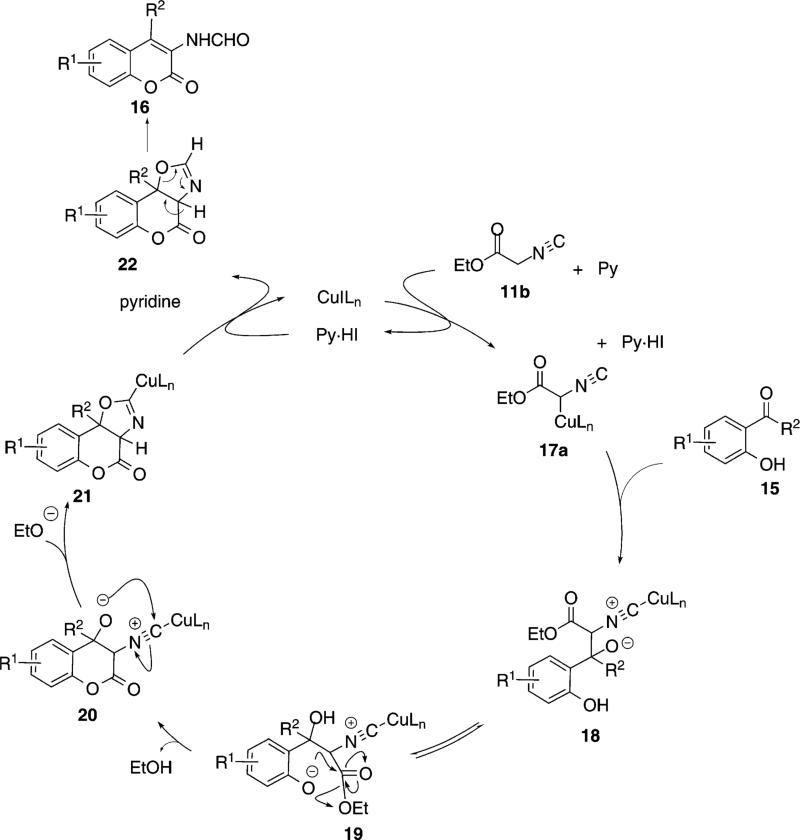

The formation of aminocoumarin 16 involves inter- and intramolecular events. Copper iodide complexes to isonitrile 11b and, in the presence of pyridine, forms the copper enolate 17a (Scheme 2).[24] The structure of the copper enolate 17a has not been determined and although depicted with copper bound to carbon, the solution species could be an oxygen-bound enolate or an equilibrium mixture of the two species. Attack of 17a on the carbonyl of 15 affords 18. Proton transfer within 18 generates 19 which is poised for an intramolecular lactonization to afford 20. Cyclization of the alkoxide 20 on the activated isonitrile affords 21, a process which may precede closure of the lactone. Protonation of the copper-carbon bond of 21, opening of the oxazoline 22, and reprotonation, affords the aminocoumarin 16.

Scheme 2.

Copper-catalyzed aminocoumarin synthesis.

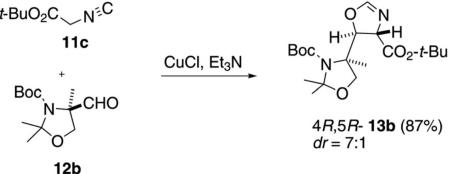

Despite the wealth of catalysts developed for the isocyanoacetate aldol condensation, the synthesis of manzacidin B represents the first use of this reaction in total synthesis. A key step in the synthesis employed catalytic CuCl in the condensation of tert-butyl isocyanoacetate (11c) with oxazolidine aldehyde 12b [Eq. (7)].[25] The facial attack on the aldehyde is dictated

|

(7) |

by the aminal chirality whereas CuCl controls the diastereoselectivity, favoring the trans-oxazoline 13b.[25]

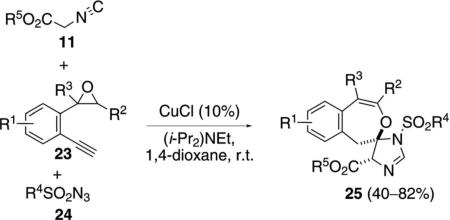

The copper-catalyzed reaction of isocyano ester 11, 2-(2-ethynylphenyl)oxirane 23 and sulfonyl azide 24, [Eq. (8)] proceeds through two catalytic cycles to give

|

(8) |

spirocyclic imidazolines 25 (Scheme 3 and Scheme 4).[26] Solvent and base were screened and the aromatic substituents (R1=H, Cl, F, OMe) of the epoxide substrate were varied.

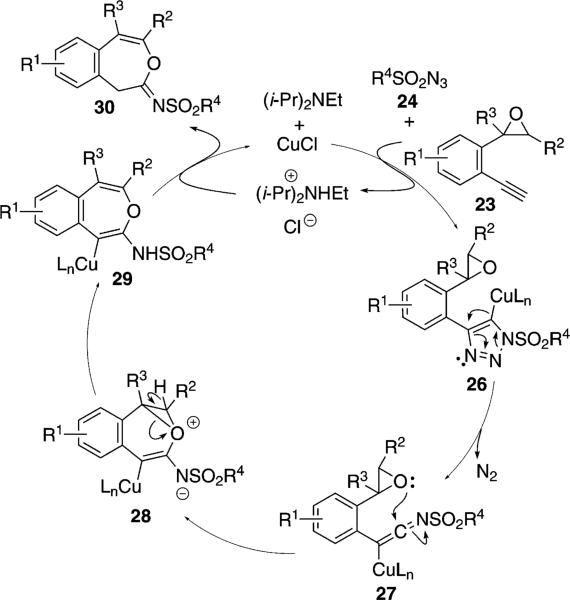

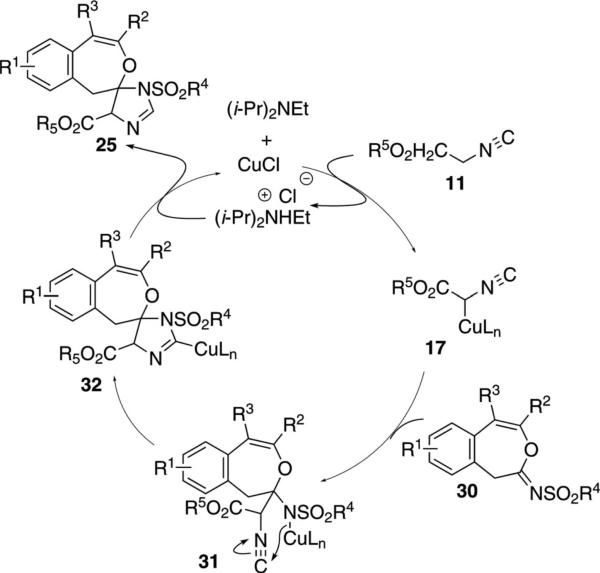

Scheme 3.

Copper-catalyzed epoxide–alkyne cyclization.

Scheme 4.

Formal [3+2]isonitrile route to spiro imidazolines.

In the first catalytic cycle, CuCl catalyzes the condensation of epoxide 23 with the sulfonyl azide 24 to generate 30 (Scheme 3). Presumably the reaction proceeds via a copper-catalyzed deprotonation of 23 with (i-Pr)2NEt followed by cycloaddition with 24. Copper migration and loss of nitrogen from 26 forms the ketenimine 27. Intramolecular nucleophilic attack of the epoxide onto the ketenimine leads to 28 that engages in a ring opening proton transfer to furnish 29. Protonation of 29 regenerates CuCl and releases imine 30.

The condensation of imine 30 with isocyanoacetate 11 is formally a CuCl-catalyzed [3+2]cycloaddition (Scheme 4). CuCl-assisted deprotonation of isocyano acetate 11 affords 17 that attacks imine 30 to form 31. Intramolecular cyclization of 31 to 32 and protonation of the carbon-copper bond affords the imidazoline 25 and regenerates CuCl and (i-Pr)2NEt.

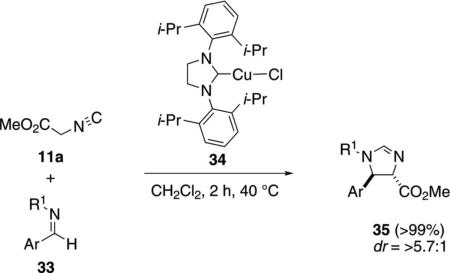

Screening various ligands with CuCl identified complex 34 as an effective catalyst for the condensation of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) with imines 33 [Eq. (9)]. The yield was quantitative with a high preference for trans-imidazolines 35.[27]

|

(9) |

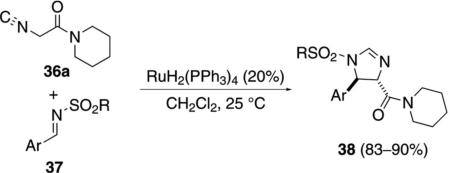

The ruthenium-catalyzed reaction of isocyanoacetamide 36a with N-sulfonylimines 37 affords trans-2-imidazolines 38 [Eq. (10)].[28] When less than

|

(10) |

20 mol% catalyst is used, the yield of 2-imidazoline 38 decreases and an oxazole is formed competitively.

Although the mechanism of the ruthenium condensation is not known, the catalytic cycle likely follows the general isonitrile-aldol sequence (Scheme 1). Isonitrile activation by ruthenium presumably generates a metallated isonitrile or an enolate that condenses with the imine through either a [3+2]cycloaddition or by sequential addition–cyclization and protonation.

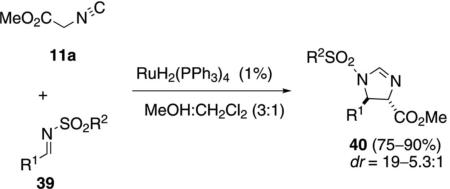

RuH2(PPh3)4 catalyzes a similar condensation of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) with N-sulfonylimines 39 to afford trans-imidazolines 40 [Eq. (11)].[29] A methanol-dichloromethane solvent mixture provided the optimal diastereoselectivity and chemical yield. Tosyl- and phenylsulfonylimines having aliphatic and aromatic substituents react equally well.

|

(11) |

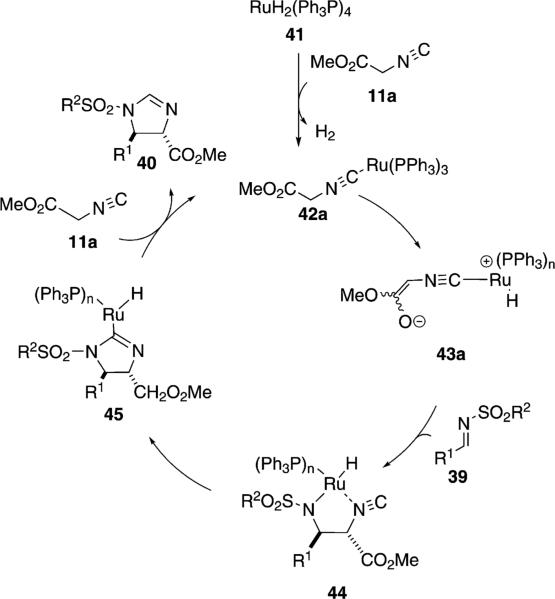

The active catalyst 42a, for the condensation of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) with 39, is presumed to form via hydrogen extrusion from RuH2(PPh3)4 and coordination of Ru(PPh3)4 to 11a (Scheme 5). Oxidative addition of ruthenium into one of the acidic methylene protons affords the enolate 43a that attacks imine 39 to afford the ruthenacycle 44. Migration of the metal-nitrogen bond with concomitant attack on the isonitrile carbon affords 45. Coordination of another isonitrile 11a and reductive elimination regenerates active catalyst 42a and affords the trans-imidazoline 40.

Scheme 5.

Ruthenium-catalyzed isocyanoacetate condensation with imines.

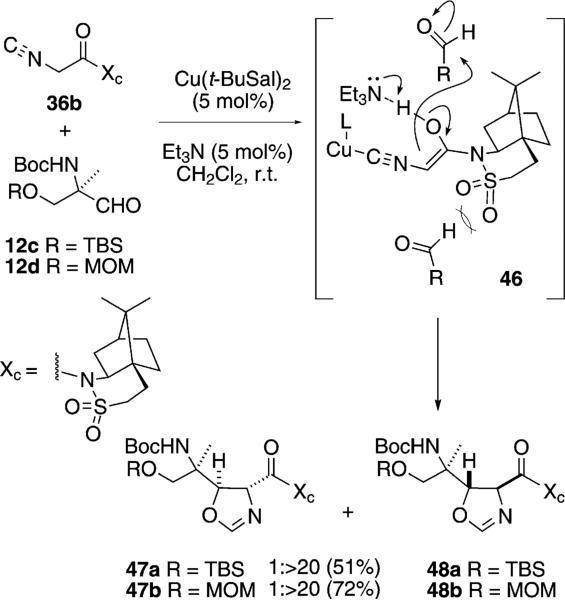

An aldol condensation of the chiral isonitrile-amide 36b with the chiral aldehydes 12c or 12d was highly stereoselective (Scheme 6).[30] Screening copper sources identified a copper salen complex as the most diastereoselective metal. The selectivity is rationalized by assuming that the copper-complexed isonitrile eno-late 46, selectively attacks the aldehydes 12c or 12d from the top face.

Scheme 6.

Double stereodifferentiation in an isonitrile aldol-type condensation.

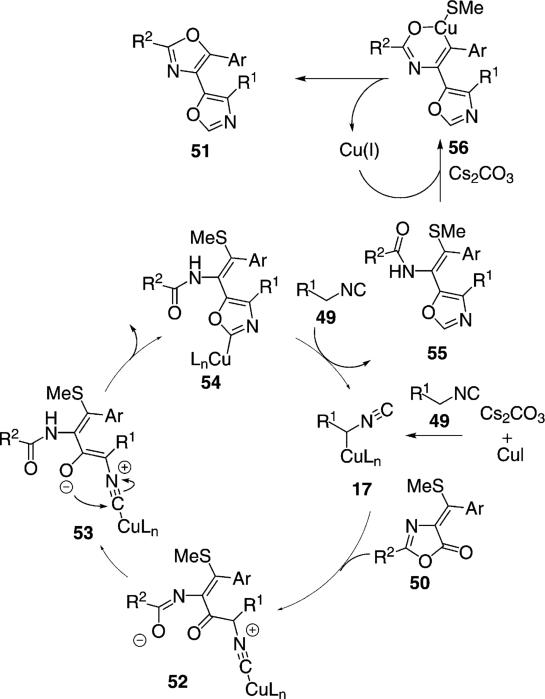

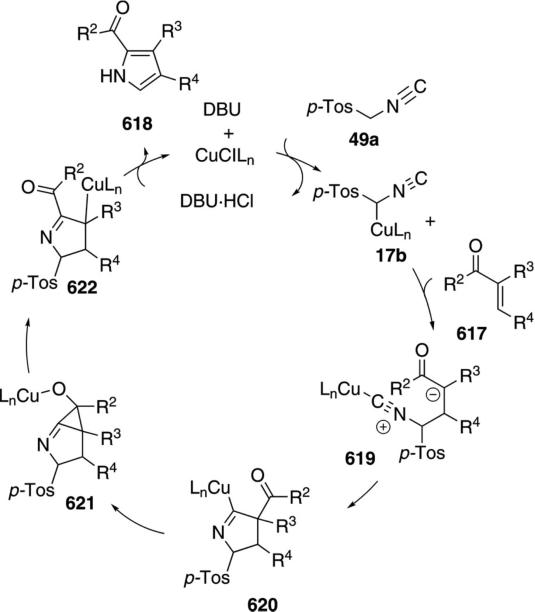

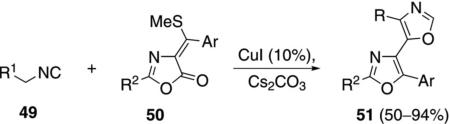

Catalytic copper iodide promotes the reaction of activated isonitriles 49 with oxazolones 50 to form bisoxazoles 51 [Eq. (12)].[31] The isonitrile activating

|

(12) |

group can be sulfonyl, ester, pyridyl, amide, or a substituted phenyl group.

As with many copper-catalyzed reactions with activated isonitriles, the copper facilitates deprotonation to afford an isocyano enolate (49→17, Scheme 7). Attack of enolate 17 onto the carbonyl of 50 generates enolate 52 which engages in a proton transfer to form enolate 53. Cyclization of 53 leads to 54. Protonation of 54 by the activated isonitrile releases 55 that reacts with a copper(I) species accompanied with deprotonation by Cs2CO3 to afford 56. Reductive elimination from 56 releases the copper(I) species and the bisoxazole 51.

Scheme 7.

Copper-catalyzed bisoxazole formation.

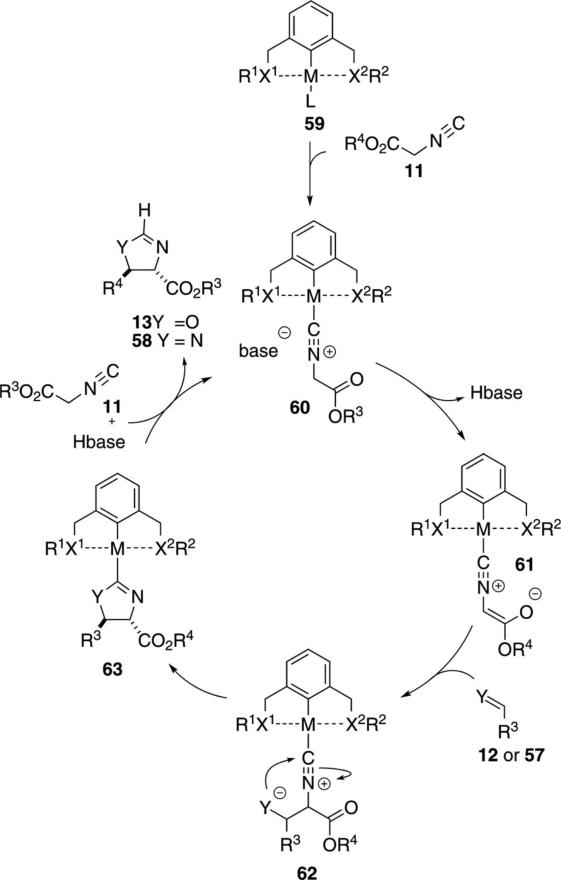

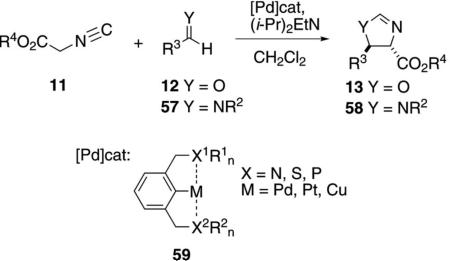

Pincer metal complexes 59 have been used extensively in platinum- and palladium-catalyzed aldol condensations to afford oxazolines 13 and imidazolines 58 [Eq. (13)]. The condensations exhibit a high preference

|

(13) |

for the trans-diastereomer in which the alkyl group R3 and the ester reside on opposite sides of the oxazoline or imidazoline ring.

All pincer complexes catalyze the aldol condensation of isocyanoacetates via essentially the same catalytic cycle (Scheme 8). The pincer precatalyst typically has a labile ligand (halide, water, triflate), providing a vacant coordinating site for isocyanoacetate 11 to bind to. Mechanistic studies show that the isonitrile binds particularly strongly to the metal center, implying that the palladium-isonitrile bond is best considered as a covalent bond.[32] Deprotonation of the metal-bound isonitrile is facile and does not necessarily require added base to form the enolate 61. The slow step of the pincer-catalyzed aldol condensation is the attack of the coordinated isonitrile enolate 61 on the aldehyde or imine.[33] Subsequent internal attack on the isonitrile transforms 62 to the metallated heterocycle 63. Coordination of 11 and concomitant protonation of 63, releases the heterocycle and the pincer complex 60.

Scheme 8.

Pincer-catalyzed aldol cyclization.

Pincer complexes vary primarily in the nature of the ligated heteroatom coordinated with the metal ion and in the substituents on this ligand. Although the metal ion can be varied, palladium is the most common metal used in pincer complexes for isocyanoacetate condensations. Usually the diastereoselectivity is very high. Many catalysts incorporate a deep binding pocket at the metal site to create a chiral environment for imparting enantioselectivity. Despite much variation, high enantioselectivity remains elusive.[34]

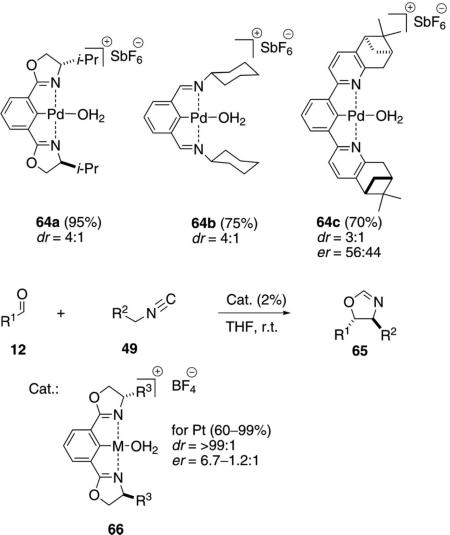

2.1 Aldol Condensations with C2-Symmetrical NCN Pincer Complexes

The oxazoline-derived pincer complexes 64a–c catalyze the condensation of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) with benzaldehyde (12a) to form the trans-oxazoline 13a [Eq. (14)].[34] No enantioselectivity was reported, which is typical for this type of pincer-catalyzed condensation. The iminocyclohexane pincer complex 64b exhibits a very similar profile affording 13a with a dr of 4:1. Similarly, the chiral bis-pyridine complex 64c catalyzes the formation of 13a (dr=3:1) but the background reaction accounts for at least 50% of the conversion. Not surprisingly, the isoxazole 13a was racemic.[35] The corresponding platinum complex exhibits the same diastereoselectivity profile.

Pincer-catalyzed condensations of TosMIC (49a, R2=SO2Tol) with various aldehydes exhibited the best selectivity with the cationic aqua platinum catalyst 66 (M=Pt) [Eq. (15)].[36] The tert-butyl-substituted complex 66 (R3=t-Bu) was virtually inactive whereas the enantioselectivities using Ph, Bn, and s-Bu alkyl substituents were distinctly lower than that

|

(14) |

|

(15) |

of the corresponding i-Pr complex. Only the trans-diastereomer was detected with reasonable levels of enantioselectivity. Analogous condensations of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) with aldehyde 12 and catalyst 66 (M=Pt, R3=i-Pr) were distinctly less selective than for the corresponding condensation with TosMIC.

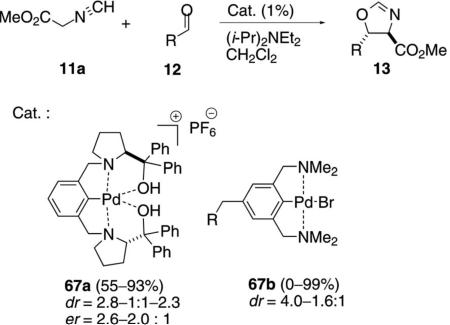

The diphenylhydroxymethylpyrolidinyl pincer complex 67a catalyzes the condensation of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) with aromatic aldehydes 12 [Eq. (16)].[36] Although the preference for the trans diastereomer

|

(16) |

is modest, there is a changeover with ortho-methoxybenzaldehyde in favoring the cis diastereomer. Most interesting is a modest enantioselectivity in the condensation, which is higher for the cis diastereomer than for the trans diastereomer. There is essentially no change in the diastereoselectivity when the counter ion PF6 is replaced by BF4.

A series of complexes 67b was prepared in which the substituent R contained an amino acid linked through an amide or ester.[37] No enantioselectivity was observed for the 67b-catalyzed condensation of 11a with benzaldehyde, and the diastereoselectivity was modest.

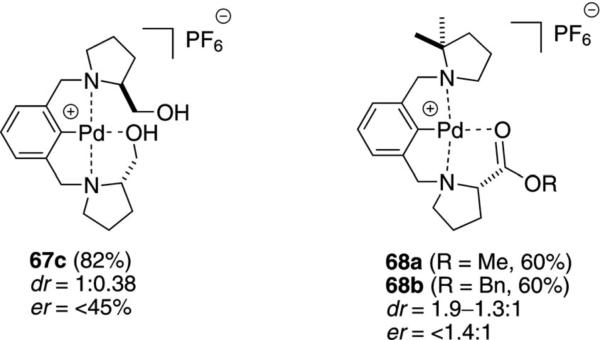

The pincer complexes 67c and 68 coordinate one hydroxy or carbonyl group to fully saturate the coordination sphere of the cationic palladium complexes (Figure 2).[34,38] Fast coordination and dissociation takes place in solution, allowing the isonitrile to coordinate and be activated by the metal center. The catalysts afforded oxazolines with modest dr and er.

Figure 2.

Cationic pincer complexes.

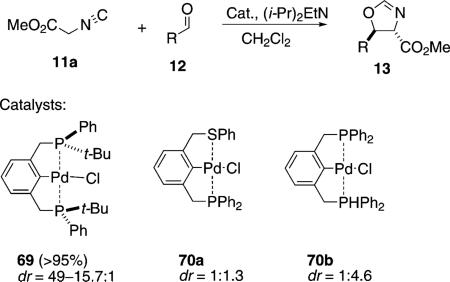

2.2 Aldol Condensations with PCP and SCP Pincer Complexes

The generally poor stereoselectivity with chiral pincer complexes such as 64a–c stimulated shifting the chirality from a nitrogenous ligand to a phosphine ligand. The C2-symmetrical phosphine pincer 69 was used to condense methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) with an aldehyde [Eq. (17)]. The diastereoselectivity was high but

|

(17) |

the enantioselectivity was never greater than 1.3:1. The platinum analogue of 69 exhibited no catalytic activity.[39]

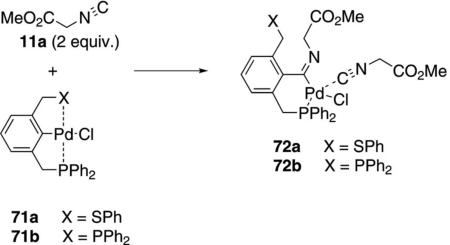

The non-symmetrical, achiral pincer complex 71a was prepared and the catalytic activity compared with that of the symmetrical pincer complex 71b [Eq. (17)].[40] Both complexes are trans-selective with non-symmetrical 71a being the least selective and most reactive.

Complexes 71a and 71b are precatalysts which incorporate isocyanoacetate to afford active catalyst 72a or 72b, respectively [Eq. (18)]. The insertion

|

(18) |

occurs by dissociation of one ligand, isonitrile coordination, followed by isonitrile insertion. For the un-symmetrical complex 72a, the phosphine remains coordinated while the PhS ligand is free.

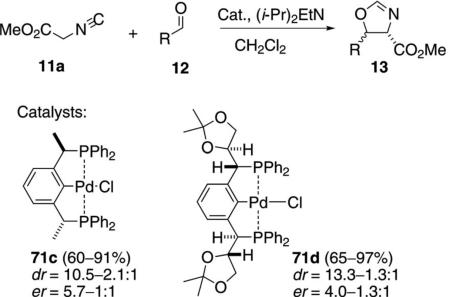

Extensive optimization with the chiral pincer complex 71c was rewarded with the highest enantiomeric ratio in a pincer-catalyzed aldol condensation [Eq. (19)].[41] Treating 71c with silver chloride provided

|

(19) |

a catalyst with significantly more activity than the platinum analogue. The aldol condensations of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) and diverse aldehydes 12 afford mixtures of trans- and cis-oxazolines 13. The highest er was obtained with mesityl aldehyde (er=5.7:1) indicating that installing chirality on the benzylic carbon is a feasible strategy for stereocontrol with pincer complexes. Catalyst 71d, bearing a chiral benzylic substituent, also reacts with a variety of aldehydes to afford trans-oxazolines with good diastereo-selectivity and similar enantioselectivity.[42]

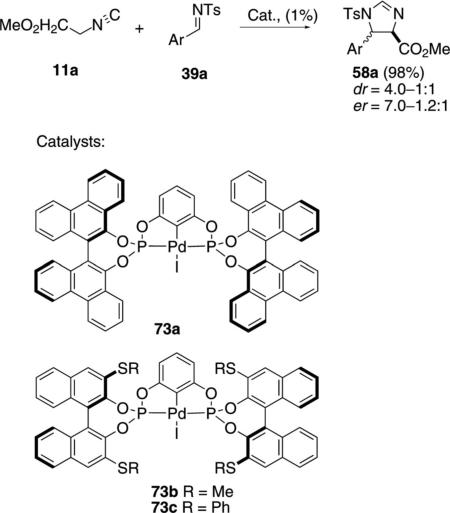

Palladium complexes 73a–c catalyze the condensation of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) with sulfinylimines 39a [Eq. (20)].[43] The biphenanthrol catalyst

|

(20) |

73a provided higher selectivity than the binol complexes 73b and 73c, although the diastereoselectivity is modest with both catalysts (4.0–1.0:1). The enantioselectivity was higher with the sterically more demanding catalyst 73a than for the corresponding binol complex 73b, affording a 7:1 enantiomeric ratio with the imine derived from benzaldehyde. All catalysts gave better enantioselectivity for the minor cis-imidazoline diastereomer.

2.3 Immobilized Pincer Complexes

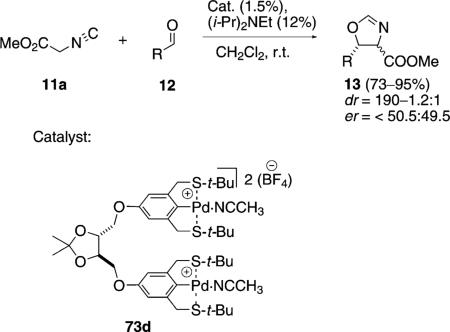

Bimetallic palladium complex 73d catalyzes the aldol condensation of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) with aldehydes 12 to form oxazolines 13 [Eq. (21)].[44] Each palladium atom is coordinated to an SCS-type ligand with the two pincer units linked by a chiral spacer. There is no cooperativity between the metal centers. The enantioselectivity is virtually non-existent as expected for such remote chirality. The chiral acetal was used to link the catalyst to silica to form a catalyst which showed essentially the same profile as catalyst 73d.

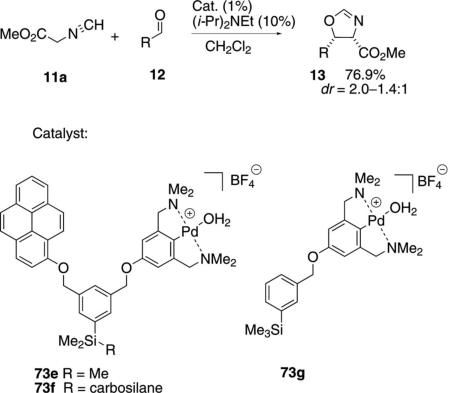

The NCN-pincer complex 73e incorporates a pyrene unit as a fluorescent tag [Eq. (22)].[45] The

|

(21) |

|

(22) |

trimethylsilyl substituent on 73e and 73g provides a solution mimic for the carbosilane-immobilized analogue 73f.[46] A related silicon tether strategy allows pincer complexes to be incorporated within dendrimers.[47] The carbosilane allows for catalyst recycling by nanofiltration. The tweezer-pincer complex 73e has a small rate enhancement relative to 73g indicating possible cation-π interaction perhaps because of a faster isonitrile ligation or association with the aromatic aldehyde. The silane complex 73f catalyzes a slower condensation than 73e, although the total turnover numbers are similar for the two catalysts.[48] The diastereoselectivity was the same with all three catalysts.

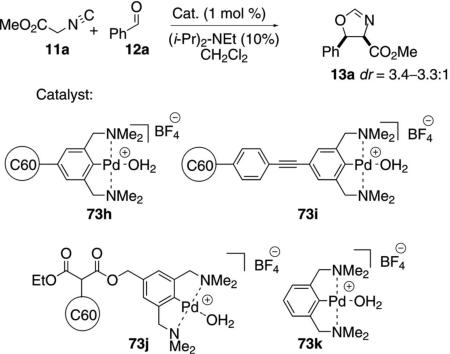

Palladium(II) bis(amino)aryl NCN pincers 73h–j were attached to C60 through three different linkers [Eq. (23)].[40] All three immobilized catalysts, and the parent 73k, gave very similar rates and diastereoselectivity. The large size of the C60-linked complexes provides retention in continuous-flow processes.

|

(23) |

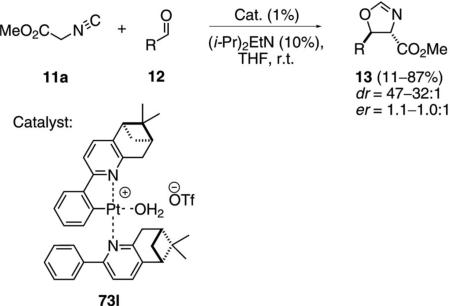

The non-symmetrical cyclometallated platinum complex 73l provides excellent diastereoselectivity in the aldol condensation of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) with aldehydes 12 [Eq. (24)].[42] In contrast, there is virtually no enantioselectivity.

|

(24) |

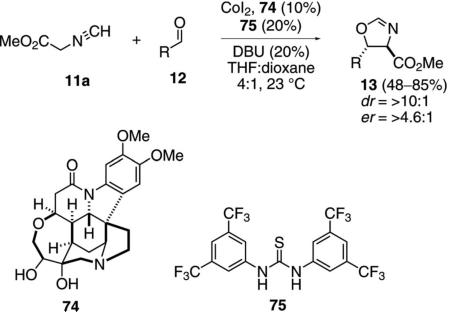

2.4 Aldol Reactions Promoted by Cooperative Catalysts

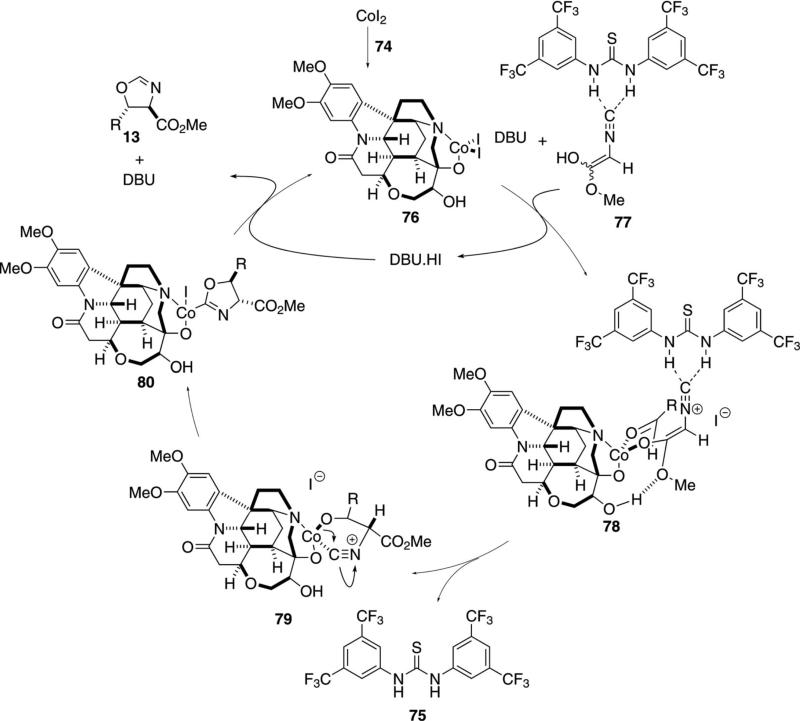

Cooperative catalysis, in which a multifunctional organic scaffold is combined with a transition metal, is emerging as a powerful tool in asymmetric synthesis. The diastereoselective condensation of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) with aldehydes (12) is representative [Eq. (25)].[50] The condensation employs CoI2, chiral ligand 74, and the thiourea organocatalyst 75. NMR analysis indicates that 75 binds to the isonitrile. Although the reaction is catalyzed by CoI2 alone, the thiourea improves the diastereomeric ratio from 1.2 to 5.7:1. Dioxane is added as a co-solvent to improve the solubility of the cobalt catalyst.

The catalytic cycle engages a thiourea-complexed isonitrile 77 with the cobalt catalyst-ligand complex 76 (Scheme 9). A downfield shift of the thiourea NH

|

(25) |

signal occurs on adding the isonitrile 11a to the thiourea 75, suggesting formation of complex 77 prior to deprotonation by DBU. Side products include an aldol arising from condensation without cyclization, consistent with isonitrile activation by the thiourea and not the metal center. Ligation of the enolate to cobalt complex 76 forms 78 in which a key hydrogen bond between the hydroxy and the enolate oxygens anchors the two groups in a specific orientation. Condensation within the preorganized complex 78 leads to 79 that cyclizes internally to provide 80. Protonation of 80 releases the oxazoline 13 and regenerates the cobalt catalyst. In addition to high selectivities, the reaction provides a high yield with both aromatic and aliphatic aldehydes.

Scheme 9.

Cooperative CoI2–organocatalysis.

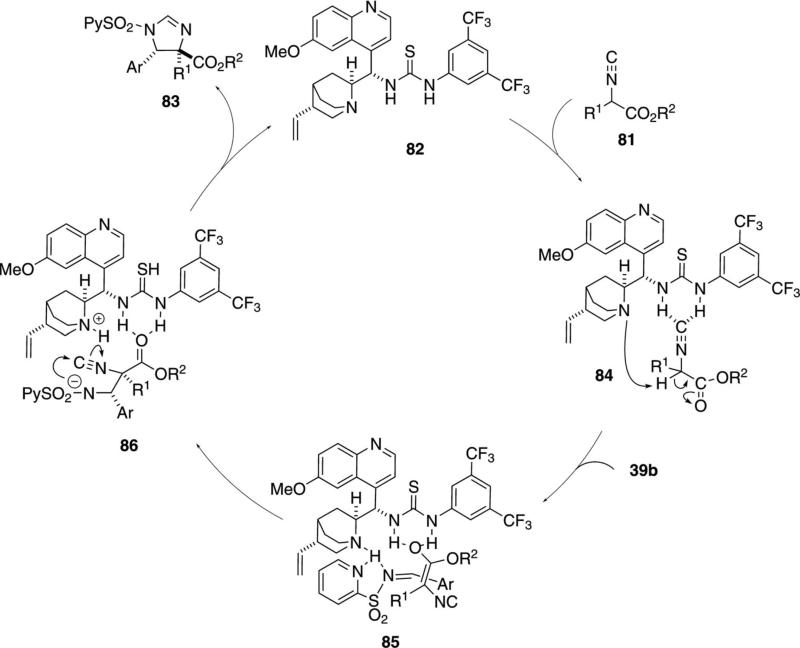

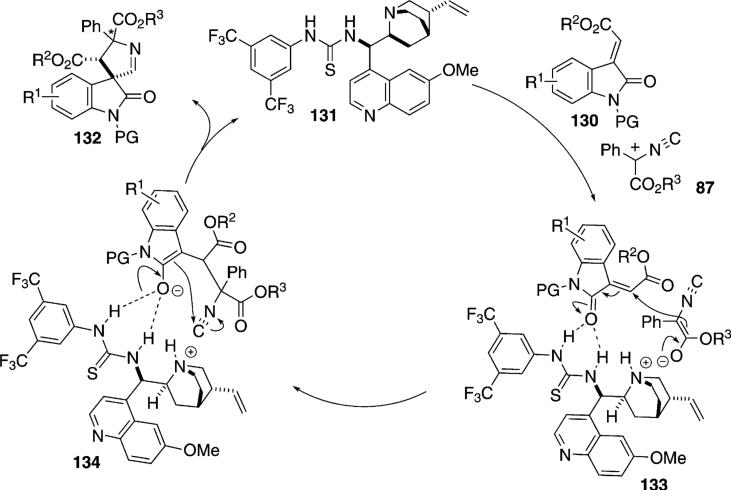

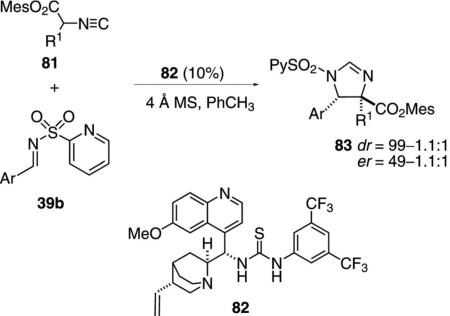

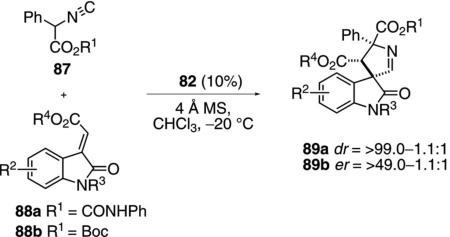

Several organocatalysts incorporate two different functional groups to bind and activate a substrate. The chiral thiourea 82 functions as a bifunctional organocatalyst in catalyzing the addition of isocyanoacetate 81 to imines 39b [Eq. (26)].[51] Extensive optimization

|

(26) |

identified the requirement for the pyridylsulfonyl imine 39b suggesting a two point binding between the catalyst and the pyridine and imine nitrogens. The reaction tolerates diverse substituents in the imine, with an aromatic substituent R1 in the isonitrile affording the best stereoselectivity.

A key design feature of organocatalyst 82 is the presence of the thiourea for hydrogen bonding to the isonitrile (Scheme 10).[52] Hydrogen bonding between the isonitrile 81 and the organocatalyst 82 aligns the complex 84 for internal deprotonation. The enolate reorganizes to 85 with the enolate oxygen complexed to the thiourea. Anchoring of the imine to the ammonium ion by the two nitrogens within 85 is speculated to control the geometry and set the stereochemistry in imidazoline 83. Attack of the sulfonamide nitrogen of 86 onto the isonitrile followed by protonation, affords 83 and regenerates catalyst 82.

Scheme 10.

Organocatalyzed imidazoline synthesis.

Organocatalyst 82 effectively catalyzes the condensation of phenyl isocyanoacetate 87 with protected methyleneindolinones 88 [Eq. (27)].[53] The reaction tolerates halogen and alkyl substituents in the indolinones. α-Alkyl isocyanoacetates are not sufficiently acidic to participate in the reaction. Subtle interactions control the stereoselectivity, with the phenyl amide-protected indoles 88a affording anti-diastereomers and Boc-protected indoles 88b favoring syn diastereomers. The catalytic cycle is presumably analogous to that for imine condensations (Scheme 10).

|

(27) |

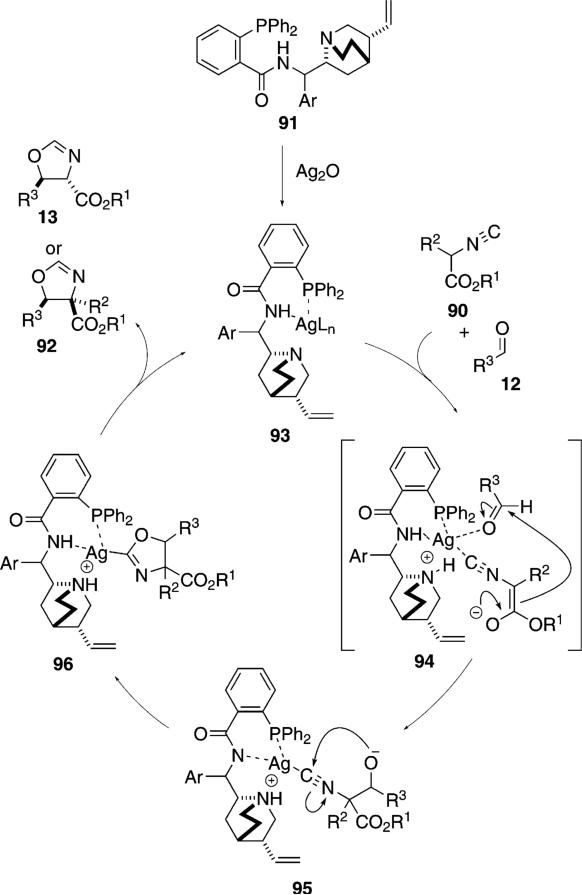

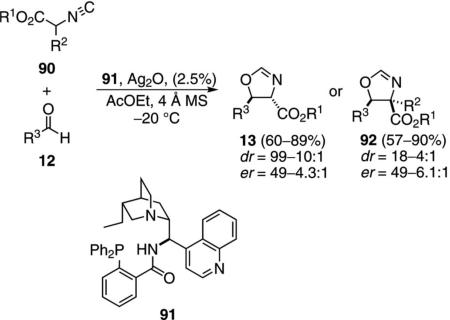

Silver oxide complexed with the chiral aminophosphine ligand 91, catalyzes the condensation of isocyanoacetate 90 with aldehydes 12 to form oxazolines 13 or 92 [Eq. (28)].[54] Control experiments establish that both silver and the ligand are required for catalysis. Aromatic aldehydes and sterically hindered aliphatic aldehydes give high selectivities. Non-substituted isocyanoacetates (90, R2=H) afford trans-oxazolines 13 whereas substituted isocyanoacetates 90 afford the cis-diastereomers 92.

The chiral phosphine ligand 91 contains a coordination site for complexing silver and a bridgehead nitrogen

|

(28) |

capable of deprotonating the activated isonitrile (Scheme 11). Complexation of silver oxide to the phosphine 91 likely creates the active catalyst 93 in situ (Scheme 11). Isonitrile complexation to 93 allows internal deprotonation by the tertiary amine, forming an ammonium ion that associates with the enolate in 94. Attack on the aldehyde is directed by the chiral environment created through complexation, leading to the alkoxide 95. Cyclization of 95 affords 96. Protonation of the silver-carbon bond by the ammonium ion releases the oxazoline 13 or 92 and allows the catalyst to re-enter the catalytic cycle.

Scheme 11.

Cooperative catalysis with Ag2O and aminophosphine 91.

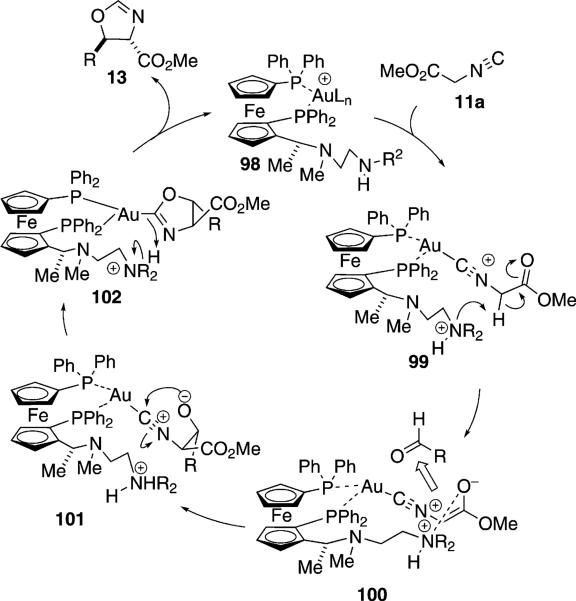

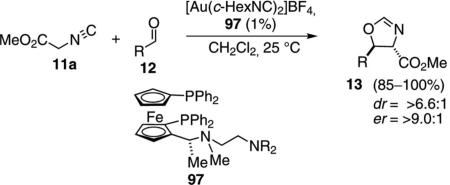

One of the first catalytic isonitrile-type aldol reactions was the condensation of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) and aldehydes 12 promoted by the bifunctional gold ferrocenylphosphine complex formed with ligand 97 [Eq. (29)].[55] Modification of the terminal amino

|

(29) |

group has a significant influence on the diastereoselectivity.[56] Solution NMR analysis of analogues in which the stereochemistry of the secondary methyl group is varied indicate that the substituent controls the conformation required for catalysis.[57] Changing the length of the tether decreases the selectivity.

The gold-catalyzed condensation of isocyanoacetate with aldehydes requires the planar chirality induced by the ferrocene and the chirality in the amine side chain (Scheme 12). Gold binds to the phosphorus atoms of the ferrocenyl ligand[58] to form complex 98 having a vacant coordination site that binds methyl isocyanoacetate (11a). Once bound, the activated isonitrile 99 is deprotonated by the distal amine, which NMR experiments show is in close proximity to the methylene protons (99→100). Experiments with catalysts in which the benzylic amine is replaced by a sulfide give very similar enantioselectivities, implying that the optimal chain conformation requires a heteroatom.[59] Enolate 100 remains in close proximity to the ammonium ion, exposing only the si face of the enolate for attack on the incoming aldehyde. Following condensation, 100→101, the alkoxide adds to the isonitrile carbon to form the oxazoline-gold complex 102. Protonation within 102 releases the catalyst and ejects the oxazoline 13.

Scheme 12.

Gold-catalyzed isonitrile aldol.

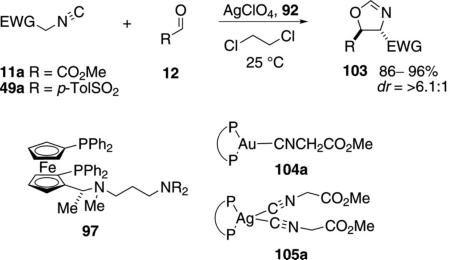

Silver-ferrocenyl catalysts condense methyl isocyanoacetate (11a)[60] and tosylmethyl isocyanide (49a)[61] with aldehydes [Eq. (30)]. The silver complex 105a catalyzes the condensation of activated methyl isonitrile with substituted aromatic, saturated aliphatic, and α,β-unsaturated aldehydes. The selectivity is

|

(30) |

lower than for the gold complex 104a but adding methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) slowly by syringe pump gives comparable selectivity. IR and kinetic data indicate that the gold catalyst adopts a tricoordinate structure 104a in which gold is bound to two phosphorus atoms and the carbon of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a). The corresponding silver complex 105a binds to the same ligand and two molecules of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a).[60] Limiting the available methyl isocyanoacetate (11a), or increasing the temperature from –10°C to 25°C, favors a tricoordinate silver structure, similar to 104a, which affords the oxazoline 103 more selectively.

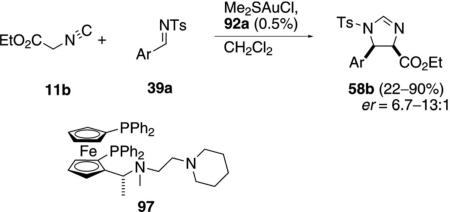

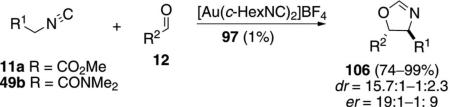

The neutral gold complex formed from Me2S·AuCl and the ferrocene ligand 97 catalyzes the condensation of 11b with imines 39a, suggesting that the same catalytic species is formed as in the aldol condesation. The catalyst condenses ethyl isocyanoacetate (11b) with imines 39a to generate cis-imidazolines 58b [Eq. (31)].[62] The enantioselectivity is not influenced by changing the electronic nature of the aromatic imine.

Bis(cyclohexyl isocyanide)gold(I) tetrafluoroborate, is distinctly less selective in the condensation of 11a

|

(31) |

with aldehydes 12. Electron deficient aromatic benzaldehydes are less selective whereas tetra- and pentafluorinated benzaldehyde form cis-oxazolines with high enentioselectivity [Eq. (32)].[63] With less than

|

(32) |

four fluorine atoms in the aromatic ring of the aldehyde, the diastereoselectivity and enantioselectivity are modest. The analogous condensation of isocyanoacetamide 49b with aldehydes does not exhibit the same stereoselectivity, affording primarily trans-oxazolines 106.[64]

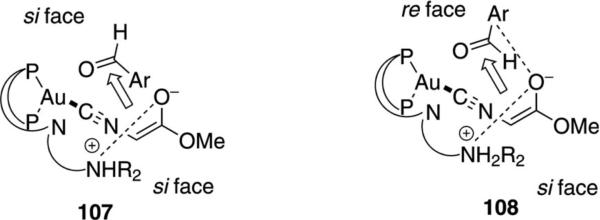

The gold-catalyzed condensations of isocyanoacetate and isocyanoacetamide proceed with the same facial selectivity on the enolate but differ in the facial selectivity on the aldehyde. For fluorinated aldehydes the usual transition structure 107 is posited to be less favorable than 108 because of an electrostatic attraction between the enolate oxygen and the electron-deficient fluoroaromatic ring (Figure 3). Possibly the enolate derived from the isocyanoacetamide suffers from steric compression in 108 and so reacts through TS 107.

Figure 3.

Stereocontrol in gold-catalyzed reactions.

3 Condensations Leading to Pyrroles and Indoles

Isonitriles have featured prominently as precursors in pyrrole syntheses.[65] In most instances the isonitrile nitrogen becomes embedded within the pyrrole as the aromatic nitrogen.

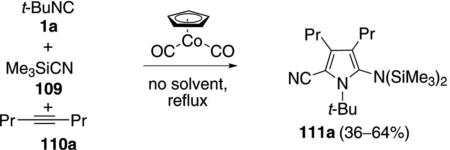

CpCo(CO)2 was found to catalyze the condensation of tert-butyl isonitrile 1a, trimethylsilyl cyanide (109), and 4-octyne (110a) to give the substituted pyrrole 111a [Eq. (33)].[66] Unfortunately the reaction is not

|

(33) |

general as variation of the isonitrile and alkyne leads to numerous pyrroles in low yield. The mechanism of this unusual reaction is not known.

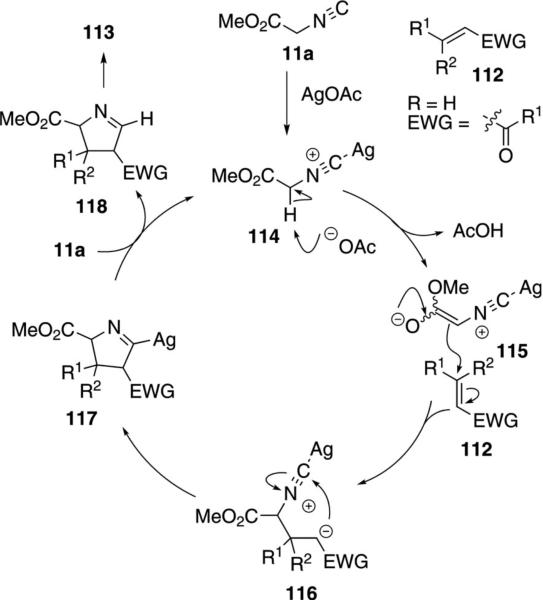

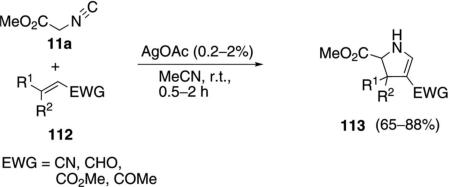

Silver acetate catalyzes the addition of methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) to activated olefins 112 leading to substituted pyrrolines 113 [Eq. (34)].[67] The reaction

|

(34) |

exhibits a high chemoselectivity in prefering conjugate addition to carbonyl addition, even with enals and enones. Mono-, di-, and trisubstituted Michael acceptors work equally well, providing variability in the number and nature of the pyrroline substituents.

Mechanistically, silver acetate catalyzes the reaction by first coordinating to methyl isocyanoacetate (11a, Scheme 13). The resulting complex 114 is activated towards deprotonation by acetate which affords the enolate 115. Michael addition of 115 to the activated olefin 112 affords a second enolate 116 which is poised for a formal 5-endo-dig cyclization. Protonation of the resulting pyrroline 117 by interaction with methyl isocyanoacetate (11a) gives the pyrroline 118 and regenerates the silver complex 114. Subsequent tautomerization of Δ1-pyrroline 118 generates the more stable Δ2-pyrroline 113.

Scheme 13.

Silver-catalyzed pyrrole synthesis.

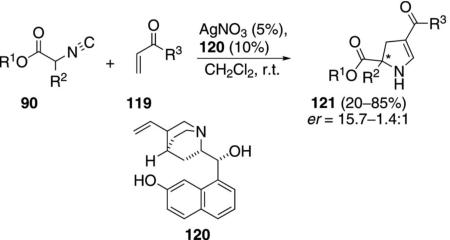

A chiral variant of the Δ2-pyrroline synthesis has been developed using a catalyst formed by complexing silver nitrate with the chiral bifunctional catalyst 120 [Eq. (35)].[68] Several silver salts promote the reaction

|

(35) |

in the absence of a quinuclidine catalyst. Only AgNO3 suppressed the background condensation while facilitating the reaction with 120. The enantioselectivity and yield are modest, though the reaction does install quaternary centers.

The catalytic cycle involves isonitrile activation by silver and chiral recognition by interaction with bi-functional catalyst 120 (Scheme 14). Complexation of isonitrile 90 with silver nitrate activates the isonitrile complex 122 toward deprotonation. Deprotonation of 122 by the quinuclidine nitrogen of 120 forms the enolate complex 123 in which an electrostatic attraction holds the enolate in a chiral environment. Facial selectivity in the attack on the Michael acceptor is attributed to H-bonding with the aromatic hydroxy group that concommitently activates the enone toward attack 123→124+125. Subsequent 5-endo-dig cyclization of enol 125 leads to pyrroline 126 which protonates and tautomerizes to the 2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrrole 121.

Scheme 14.

Silver-catalyzed enantioselective isonitrile condensation.

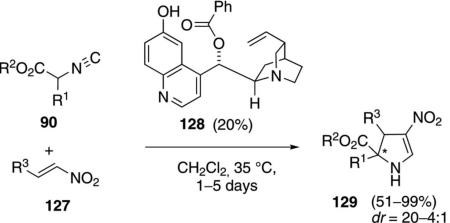

Modified Cinchona alkaloids such as 128 catalyze the cycloaddition of isocyano esters 90 with nitroolefins 127 to form 2,3-dihydropyrroles 129 [Eq. (36)].[69]

|

(36) |

The tertiary amine and the aromatic hydroxy group of 128 are essential for high selectivity. The functional group requirements of the catalyst suggest a mechanism similar to that of catalyst 120 (Scheme 14) in which the chiral base promotes the Michael addition. Diverse electronic substituents are tolerated in the nitroolefin and in the isocyano ester. Unsubstituted isocyano esters are one of the few substrates that do not react.

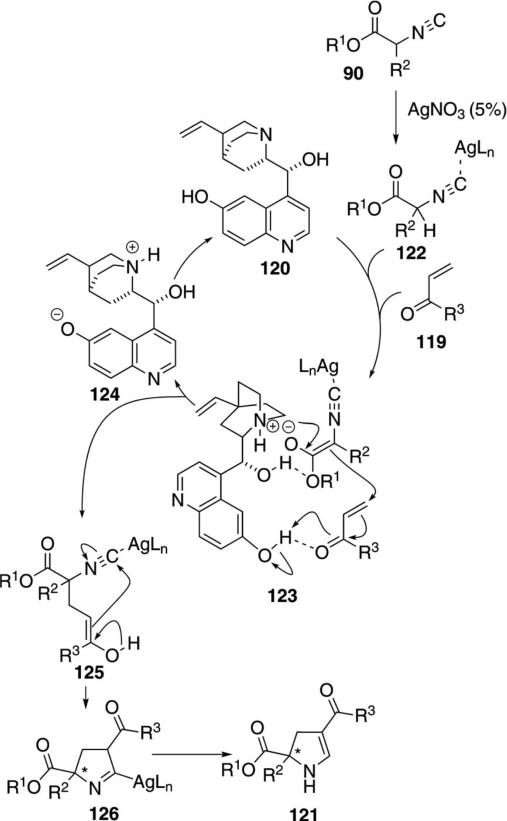

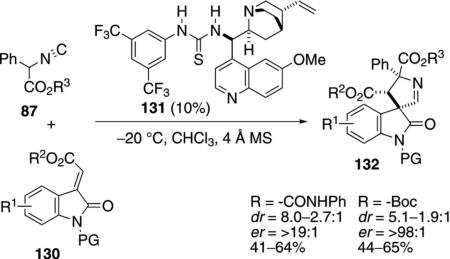

The quinolone-derived thiourea 131 catalyzes the [3+2]cycloaddition of α-phenyl isonitrile esters 87 with methyleneindolinones 130 to afford 3,3′-pyrrolinidyl spirooxindoles 132 [Eq. (37)].[70] By varying the

|

(37) |

protecting group on the methyleneindolinone, the syn- or anti-spiroindole is generated with moderate to good diastereoselectivity and with high enantioselectivity. N-Phenylamide-protected indolinones give anti-spirooxindoles in which the two ester substituents lie on opposite sides of the indoline ring. N-Boc protected indoles give primarily syn-adducts. Diverse substitution on the aromatic ring of the indolinone is tolerated.

Although a mechanism has not been proposed, surveys of similar organocatalyzed reactions establish the basic control elements likely to operate in this reaction.[71] The quinuclidine nitrogen of the catalyst 131 likely abstracts a proton from the activated isonitrile 87 to generate enolate 133 that remains close to the ammonium ion through an electrostatic interaction (Scheme 15). Internal conjugate addition of the enolate is likely directed by subtle conformational features induced by the protecting groups and the quinoline ring (133→134). Attack of the enolate 134 onto the isonitrile followed by protonation from the ammonium ion regenerates the catalyst and releases the spiroindole 132.

Scheme 15.

Organocatalyzed spirooxindole synthesis.

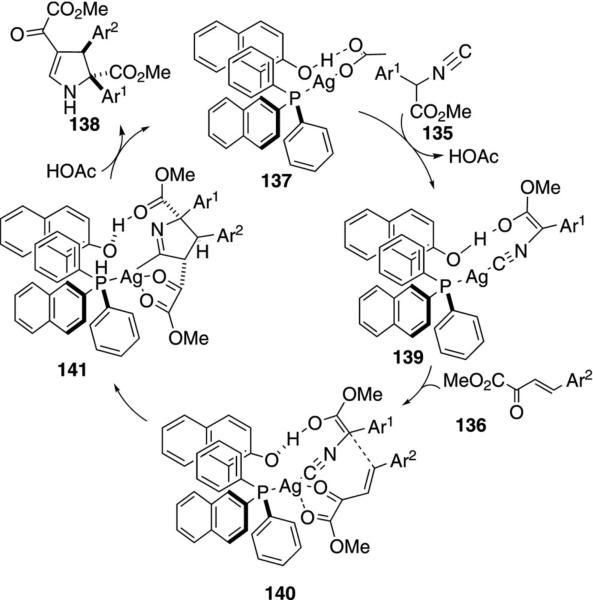

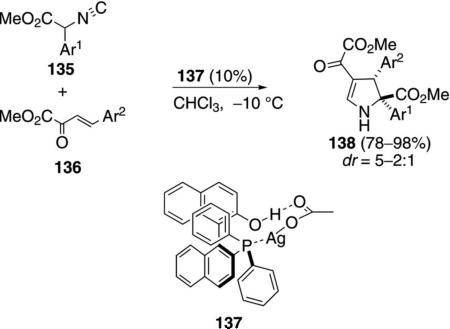

The chiral complex 137, generated from silver acetate and (S)-(2′-hydroxy-1,1′-binaphthyl-2-yl)diphenylphosphine, catalyzes the formal [3+2]cyclization of α-aryl isocyano esters 135 with 2-oxobutanoate esters 136 to afford 2,3-dihydropyrroles 138 [Eq. (38)].[72] A

|

(38) |

variety of aromatic substituents is tolerated within the 2-oxobutanoate and the isocyanoacetate.

The active catalyst is 137 that crystallizes when phosphine is added to AgOAc (Scheme 16). Complexation of 137 to isonitrile 135 leads to ejection of acetate and facilitates deprotonation of isocyanoacetate to generate the stabilized enol complex 139. Coordination of the oxobutanoate 136 to the central silver sets the orientation for the conjugate addition and subsequent cyclization 140→141. Chelation of the 2-butanoate carbonyls with the central silver enhances the electrophilicity of the double bond and orients the substrate for Michael addition to the re face. Protonation of the carbon-silver bond in 141 releases the pyrrole 138 and regenerates the silver catalyst.

Scheme 16.

Silver-catalyzed formal [3+2]isonitrile addition to oxobutenoates.

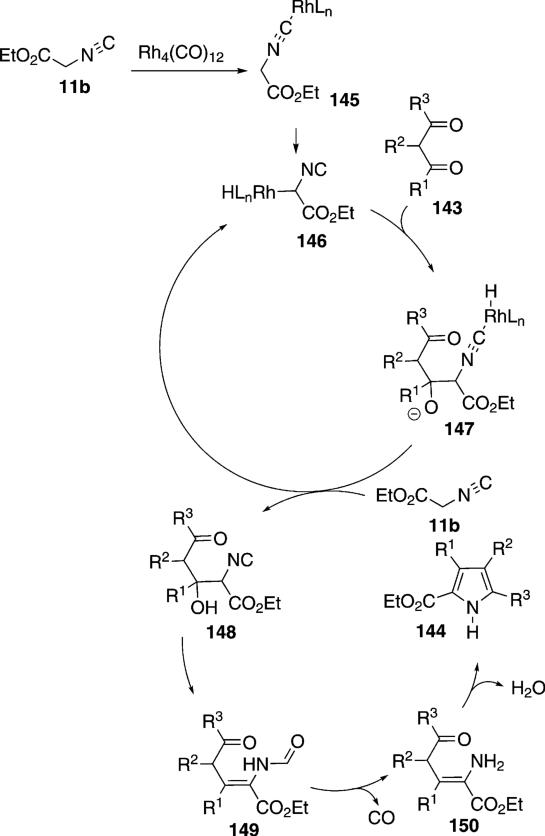

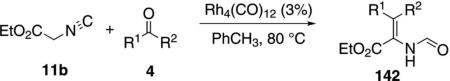

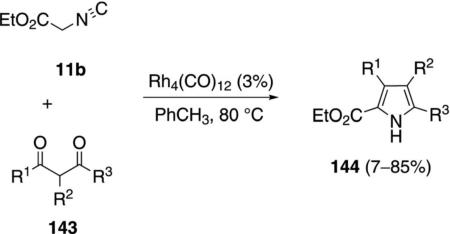

Rh4(CO)12 catalyzes the condensation of ethyl isocyanoacetate (11b) with ketones 4 to give unsaturated formamides 142 [Eq. (39)]and with diketones 143 to

|

(39) |

give substituted pyrroles 144 [Eq. (40)].[73] The regio-selectivity is dictated largely by steric compression.

The rhodium catalyst initiates the catalytic cycle by co-ordinating to ethyl isocyanoacetate (11b) and inserting into the C–H bond 145→146 (Scheme 17).

|

(40) |

Nucleophilic attack of 146 on the 1,3-diketone 143 gives the alkoxide 147. Protonation of 147 by ethyl isocyanoactate 11b gives the alcohol 148 and regenerates the rhodium catalyst 146. Isonitrile 148 eliminates water which subsequently hydrolyzes the isonitrile group to give formamide 149. Decarbonylation of 149 by the rhodium catalyst affords 150 which suffers internal condensation to give the pyrrole 144.

Scheme 17.

Rhodium-catalyzed pyrrole synthesis.

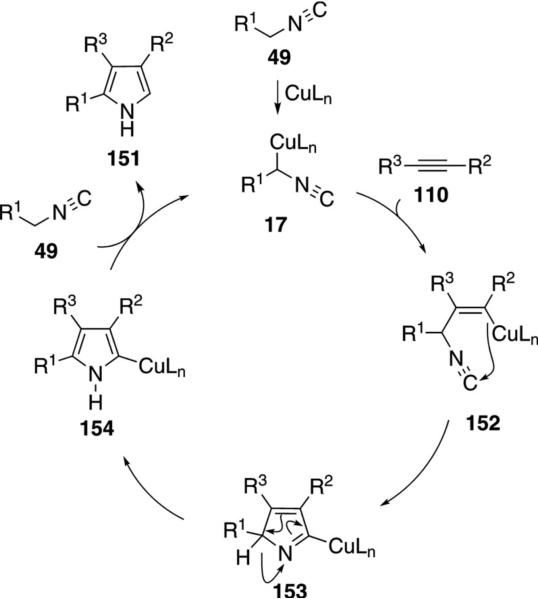

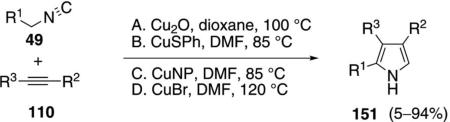

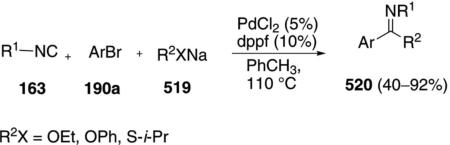

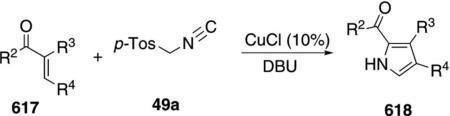

Substituted pyrroles 151 were synthesized through the copper-catalyzed addition of activated isonitriles 49 to electron-deficient alkynes 110 [Eq. (41)].[74] The reaction is catalyzed by Cu2O, CuSPh, CuBr, or copper nanoparticles. Reactions catalyzed by Cu2O

|

(41) |

require two mol equivalents of phenanthroline and are distinctly more efficient with acetylenic esters than with acetylenic ketones, nitriles, amides, or sulfones. Copper(I)benzenethiolate and copper nanoparticles were employed in DMF at 85°C. An additional catalyst-base[74a] combination of CuBr and Cs2CO3 (120°C) is effective with terminal alkynes not having an electron-withdrawing group.

The catalytic cycle involves metallation, cyclization and release of the copper catalyst (Scheme 18). Activation of the isonitrile 49 by copper allows facile metallation resulting in the cuprated isonitrile 17. Carbo-metallation of alkyne 110 or a Michael-type addition by cuprated isonitrile 17, leads to the vinyl-copper 152. Intramolecular cyclization of 152 generates the copper 2H-pyrrolenine 153 which undergoes a 1,5 hydride shift to afford the copper pyrrole 154. Protonation of 154 likely proceeds by coordination of the isonitrile 49, facilitating the protonation, to form the pyrrole 151 and regenerating 17. Experiments with copper catalysts and terminal alkynes implicate a similar mechanism.[74a] Recent experiments with Ag2CO3 and terminal alkynes are suggested to proceed through a [3+2]cycloaddition.[75]

Scheme 18.

Copper-catalyzed pyrrole synthesis.

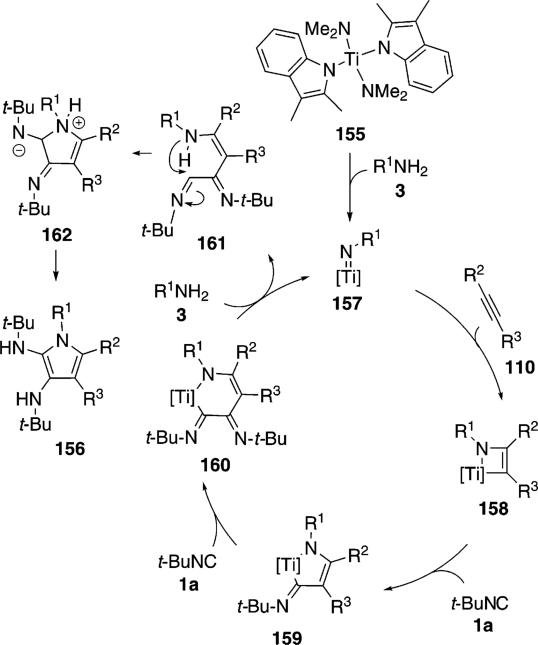

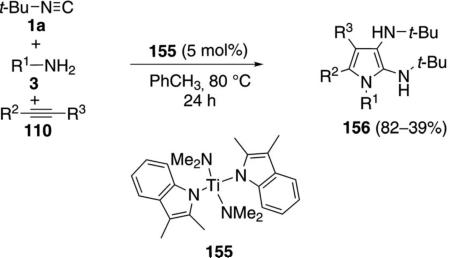

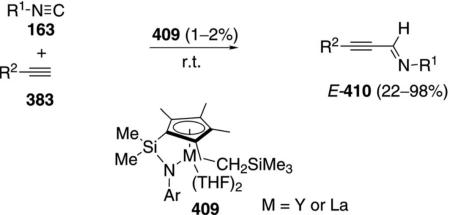

The titanium complex 155 catalyzes the condensation of t-BuNC (1a) with an amine 3 and an alkyne 110 to form pyrroles 156 [Eq. (42)].[76] Terminal alkynes 110 (R3=H) react more efficiently than internal

|

(42) |

alkynes 110. Only aromatic amines engage in catalysis.

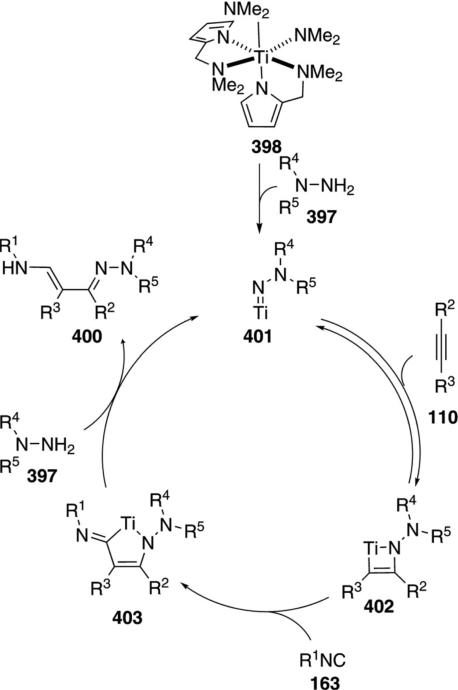

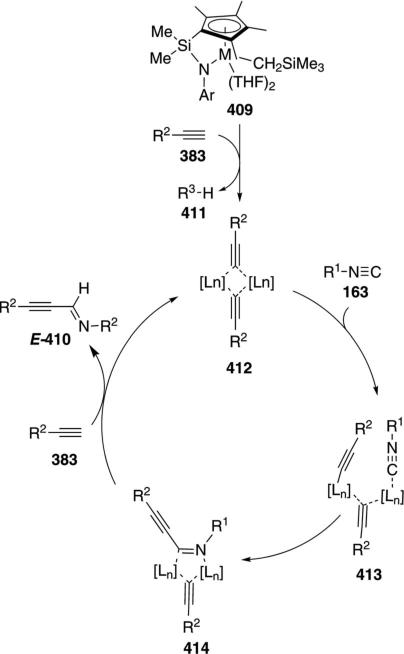

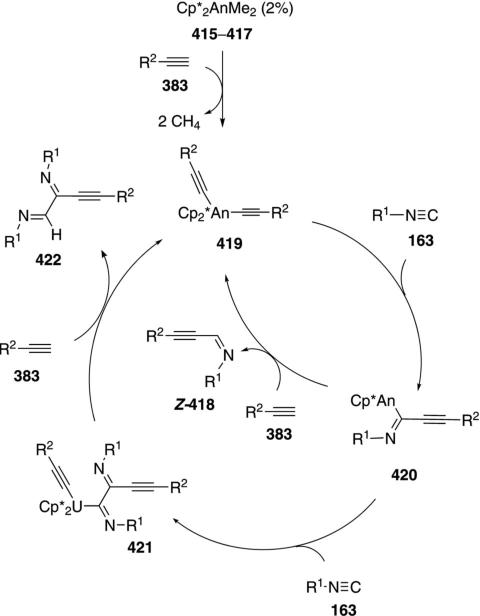

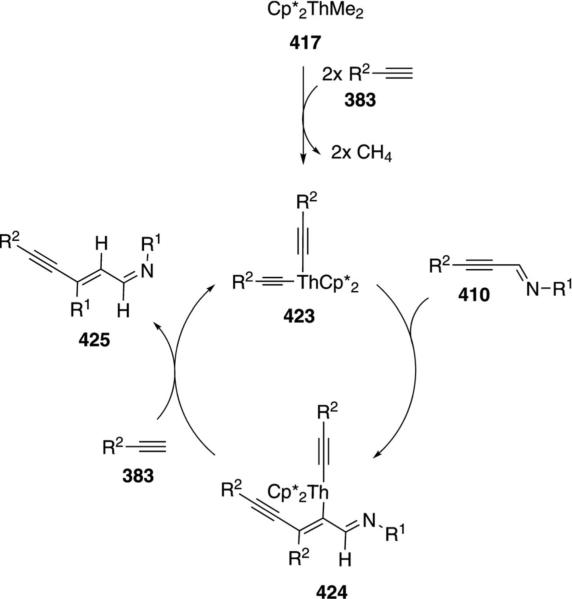

An essential feature of the cataylic cycle is formation of a formal titanium nitrene 157, which allows [2+2]cycloaddition to form titanocycle 158, and insertion of t-BuNC (1a) to form 159 (Scheme 19). Using indolyl titanium pre-catalyst 155, a second isonitrile insertion occurs after formation of 159, transforming 159 to 160. Further isonitrile insertions are disfavored because they involve formation of a 7-membered titanocycle. Coordination of amine 3 causes protonation of the metal bonds, delivering the catalyst 157 and releasing imine 161. Intramolecular cyclization 161→162, proton transfer, and tautomerization deliver the pyrrole 156.

Scheme 19.

Titanium-catalyzed pyrrole synthesis.

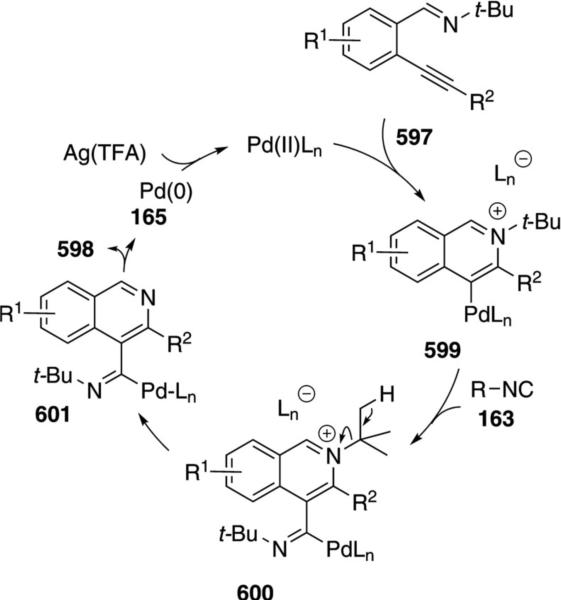

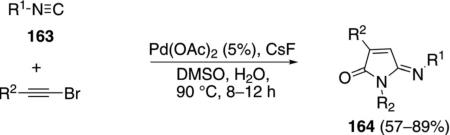

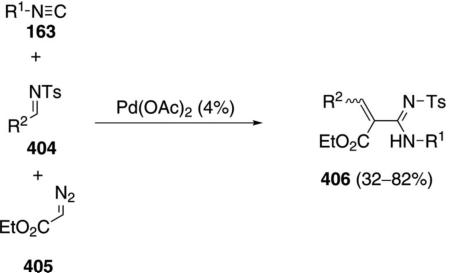

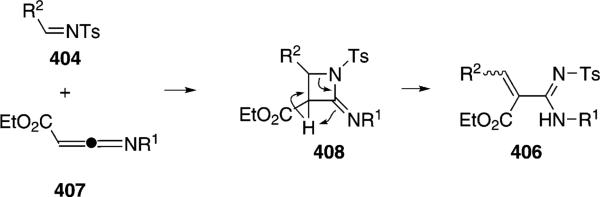

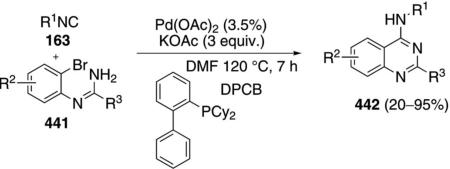

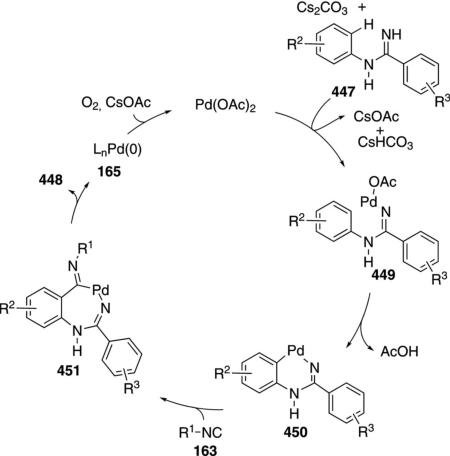

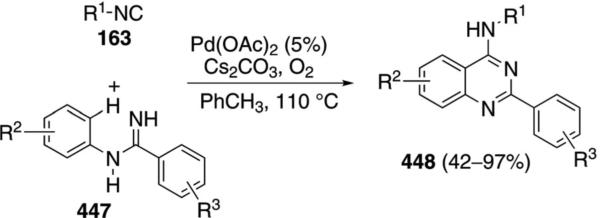

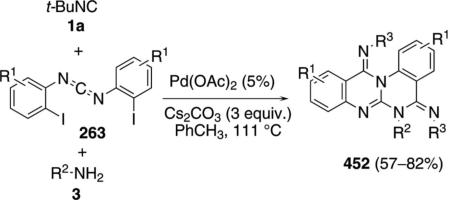

Palladium acetate catalyzes the formation of 5-iminopyrrolones 164 from two equivalents of an isonitrile 163 and a bromoalkyne 110b [Eq. (43)].[77] Performing the reaction in a stepwise fashion allows control

|

(43) |

over the iminopyrroline substituents. Alkyl and aryl substituents are tolerated in both the alkyne and the isonitrile. Isocyanobenzene and isocyanoacetate gave low yields.

The catalytic cycle rests on the in situ formation of bromoacrylamide 166 from bromoalkyne 110b and isonitrile 163 (Scheme 20). The reaction proceeds in two stages; CsF promotes the addition of the isonitrile 163 to the bromoalkyne 110b and the subsequent hydrolysis to the β-bromoacrylamide 166, whereas Pd(OAc)2 catalyzes the insertion and cyclization reaction. Oxidative addition of zero-valent palladium species 165 to the bromoacrylamide 166 affords the vinyl-palladium complex 167 which inserts an equivalent of isonitrile 163 to afford 168. Internal complexation of palladium to the amine facilitates deprotonation which transforms 168 to palladacycle 169. Reductive elimination of palladium from 169 affords the 5-iminopyrrolidinone 164 and regenerates the catalyst.

Scheme 20.

Palladium-catalyzed synthesis of 5-iminopyrrolones.

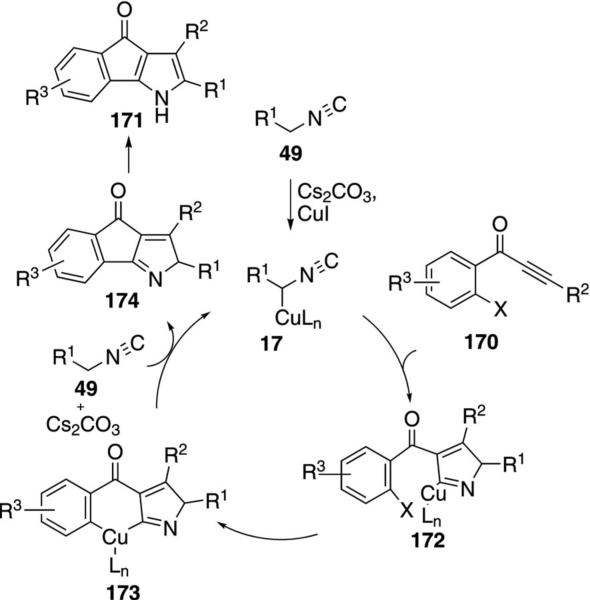

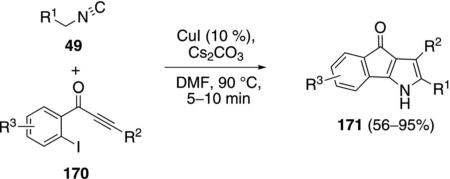

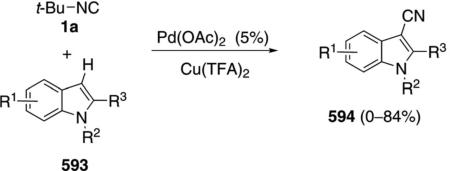

Several iodoaryl Michael acceptors were coupled with activated isonitriles to afford oxindeno[1,2-b]pyrroles. Copper iodide catalyzes the coupling of isonitriles 49 and 1-(2-iodoaryl)-2-yn-1-ones 170 to give 4-oxoindeno[1,2-b]pyrroles 171 [Eq. (44)].[78] Alkyl and aryl substituents R2 are tolerated on the alkyne

|

(44) |

whereas the isonitrile substituent R1 must be an electron-withdrawing group.

The key catalytic species is the cuprated isonitrile 17 formed by complexation of CuI to 49 followed by deprotonation (Scheme 21). Formal [3+2]cycloaddition of 17 onto ynone 170 gives the arylcopper 172. Intramolecular insertion of copper into the aryl C–I bond likely affords the copper(III) species 173. Reductive elimination from 173 ejects 174 that subsequently tautomerizes to the 4-oxoindeno[1,2-b]pyrrole 171. The copper(I) species generated during the reductive elimination, engages with the isonitrile to reform the catalyst 17.

Scheme 21.

Copper-catalyzed 4-oxoindeno[1,2-b]pyrrole synthesis.

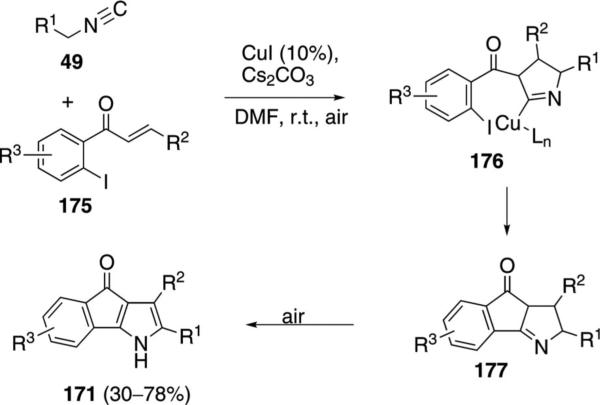

Using the same catalyst system, 4-oxoindeno[1,3-b]pyrroles 171 are synthesized by coupling activated isonitriles 49 with 1-(2-haloaryl)enones 175 (Scheme 22).[79] An initial cycloaddition 175→176 is followed by cyclization 176→177 that follows the same copper catalytic cycle as with 170 (Scheme 22). An air oxidation aromatizes 177 to afford 171.

Scheme 22.

Copper-catalyzed isonitrile addition–cyclization–oxidation.

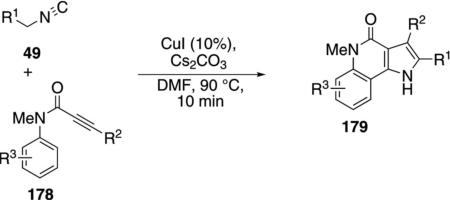

The same copper coupling stategy was employed with N-(2-haloaryl)propiolamide 178 and the activated isonitrile 49 to yield pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolin-4-ones 179 [Eq. (45)].[80] The analogous coupling with alkynoates

|

(45) |

was unsuccesful. Alkyl and aryl substituents R2 are well tolerated on the alkyne side chain of 178 as are electron-withdrawing or donating groups R3 on the aromatic ring. Electron-withdrawing groups on the aryl group of propiolamide 178 activate the substrates in the coupling process.

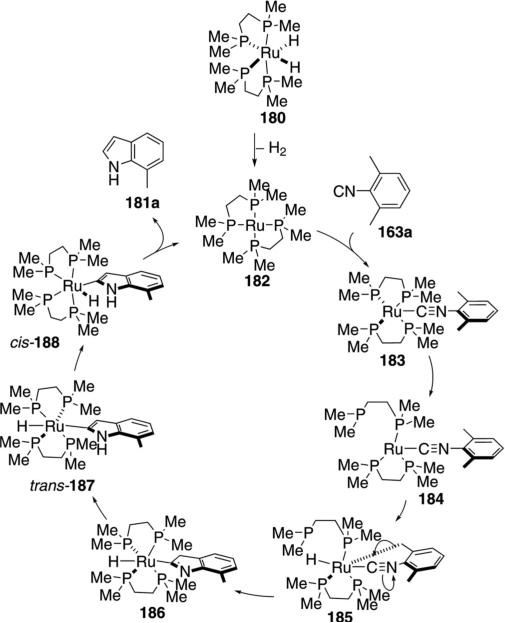

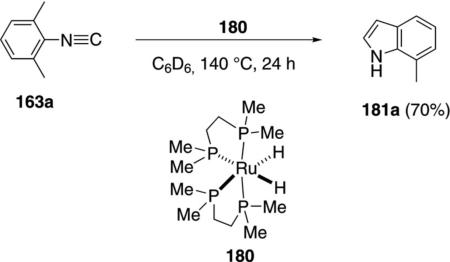

The ruthenium complex 180 catalyzes an unusual synthesis of 7-methylindole 181a from 2,6-xylyl isonitrile 163a [Eq. (46)].[81] The reaction is limited to 2,6-xylyl

|

(46) |

isonitrile because less substituted isonitriles remain complexed to the catalyst. High temperatures are required for the reductive elimination and catalyst turnover.

The mechanism involves loss of hydrogen gas from the ruthenium precatalyst 180 to give the true catalyst 182 (Scheme 23). Ligation of catalyst 182 to isonitrile 163a affords 183. Release of one of the phosphines (183→184) exposes two free coordination sites, allowing ruthenium insertion into the benzylic C–H bond to give the ruthenacycle 185. Alkyl migration within 185 to the isonitrile group forms the heterocycle 186 which tautomerizes to form the indole 187. A trans-to cis-isomerization allows the reductive elimination from cis-188 to afford the indole 181a.

Scheme 23.

C–H insertion–cyclization with RuH2(dmpe)2.

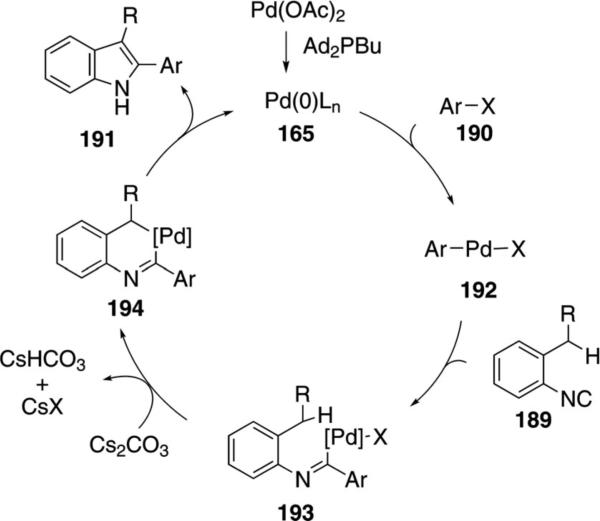

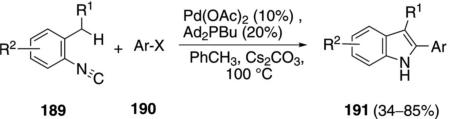

In C–H activation couplings with isonitriles, palladium catalysts generally have a greater substrate scope than the ruthenium catalyst 180. Pd(OAc)2 and Ad2PBu form a complex that catalyzes the coupling of ortho-alkylaryl isonitriles 189 with aryl iodides or bromides 190 to afford indoles 191 [Eq. (47)].[82] Electron-donating

|

(47) |

and electron-withdrawing substituents R2 are tolerated at the para-position of the isonitrile.

The catalytic cycle is initiated by an oxidative addition of zerovalent palladium species 165 into the aryl halide 190 (Scheme 24). Isocyanide insertion into 192 gives the palladium imine 193 which is poised for insertion into the benzylic C(sp3)–H bond 193→194. Reductive elimination from 194 and tautomerization affords the 2-substituted indole 191 and regenerates the palladium catalyst 165.

Scheme 24.

Palladium-catalyzed C–H insertion isonitrile coupling.

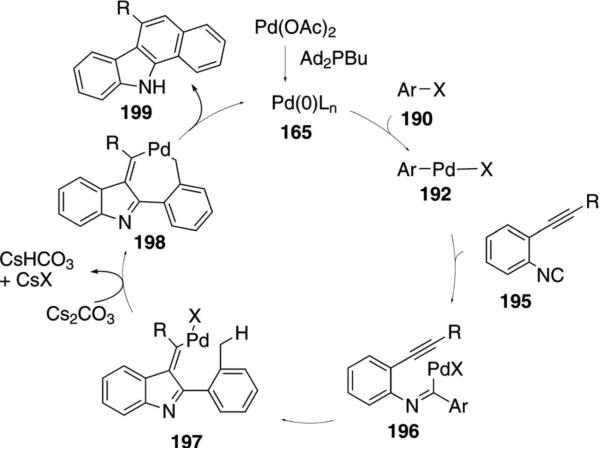

The same palladium-catalyzed C–H insertion strategy provides tetracyclic carbazoles 199 from ortho-alkynylphenyl isonitriles 195 (Scheme 25).[82] Following oxidative addition of palladium(0) into the aryl halide 190→192, isonitrile insertion affords 196. Internal carbopalladation of 196 generates 197. Insertion of the palladium(II) to the proximal benzylic C–H bond transforms 197 into 198 which reductively eliminates and tautomerizes to form 199.

Scheme 25.

Palladium-catalyzed isonitrile addition, carbopalladation, C–H insertion.

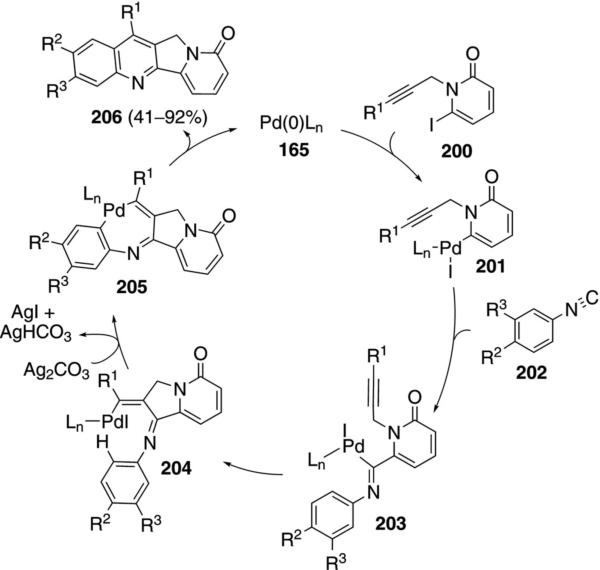

Camptothecins are accessable through a palladium-catalyzed C–H insertion process (Scheme 26).[83] Zerovalent palladium species 165 inserts into 6-iodo-N-propargylpyridone 200 to afford 201 that coordinates and inserts isonitrile 202 to form 203. Close proximity of palladium to the alkyne triggers carbopalladation to 204. C–H insertion 204→205 and reductive elimination then gives 11H-indolizino[1,2-b]quinolin-9-ones 206. Sterically encumbered substituents are tolerated at the acetylenic terminus of 200 whereas unsubstituted acetylenic pyridines are un-reactive.

Scheme 26.

Palladium-catalyzed isonitrile–insertion–C–H activation route to camptothecins.

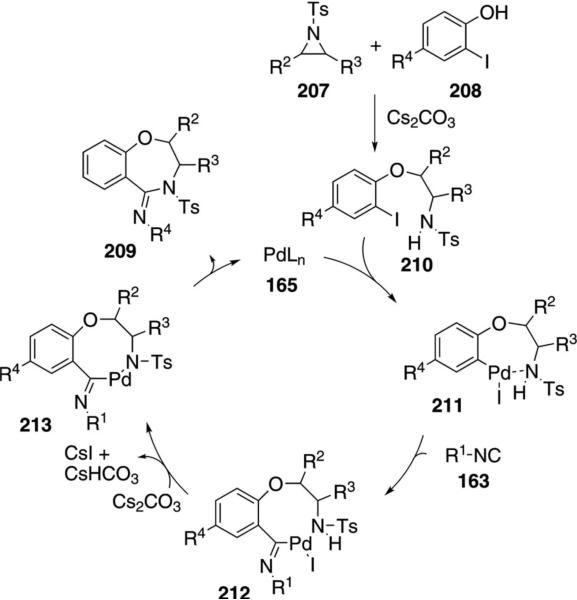

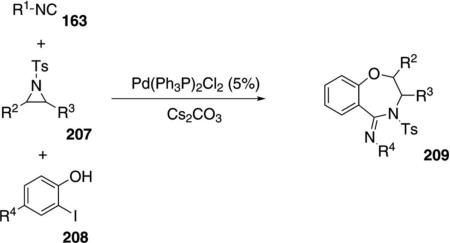

Pd(Ph3P)2Cl2 catalyzes the condensation of isonitriles 163 with N-tosylaziridines 207 and 2-iodophenols 208 to form 1,4-benzoxazepines 209 [Eq. (48)].[84]

|

(48) |

Tertiary isonitriles are most effective in the condensation, with cyclohexyl isonitrile affording the corresponding benzoxazepine distinctly less efficiently. Chloro, methyl, and phenyl substituents are tolerated in the iodophenol in equally effective condensations with cyclic or acyclic aziridines.

The condensation proceeds through base-promoted aziridine ring opening, uniting the phenol 208 and aziridine 207 into the ether 210 (Scheme 27). Insertion of palladium species 165 into the aryl iodide is proposed to afford 211 followed by isonitrile insertion and dehydrohalogenation of 212 to afford 213. Given the likely coordination in 211, which decreases the amine acidity, the dehydrohalogenation may occur prior to isonitrile insertion. Reductive elimination from 213 affords 209 and regenerates the active catalyst.

Scheme 27.

Palladium-catalyzed cyanation of 2-alkylindoles.

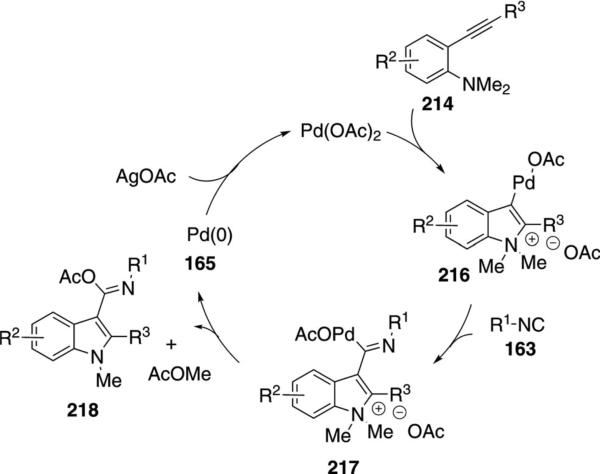

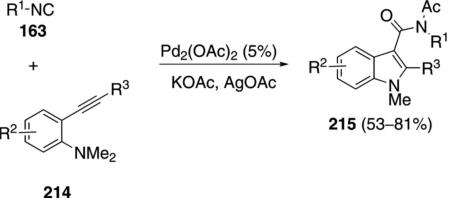

Palladium acetate catalyzes the condensation of isonitriles 163 with 2-alkynylanilines 214 to afford 3-amidylindoles 215 [Eq. (49)].[85] Primary, secondary,

|

(49) |

and tertiary aliphatic isonitriles react well but 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide failed to react. All of the successful substrates contained an aromatic or aliphatic substituent R3 on the alkyne.

Conversion of the aminoacetylene 214 into indole 215 proceeds through an initial aminopalladation (214→215, Scheme 28). Isonitrile insertion into the palladium complex 216 affords 217 that suffers demethylation and reductive elimination to generate indole 218 that subsequently tautomerizes to 215. Subjecting independently prepared 216 to the reaction conditions affords 215, providing support for the proposed mechanism.

Scheme 28.

Palladium-catalyzed isonitrile condensation affording indoles.

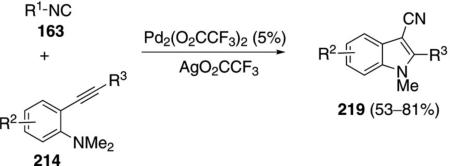

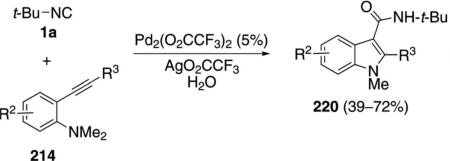

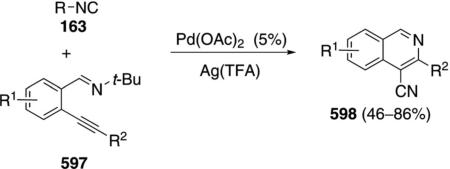

Palladium trifluoroacetate catalyzes the condensation of isonitriles 163 with aminoalkynes 214 to afford cyanoindoles 219 [Eq. (50)].[86] tert-Butyl isonitrile

|

(50) |

and cyclohexyl isonitrile react equally well, whereas 2,6-dimethylphenyl isonitrile does not participate in the reaction. Alkyl- and arylacetylene substituents react well.

The reaction mechanism presumably parallels the acylation process (Scheme 28) except for 217 suffering reductive dealkylation and a fragmentation with release of nitrile 219 rather than a reductive elimination.

|

(51) |

Supporting this change in mechanism is the addition of water to the reaction mixture which, with tert-butyl isonitrile (1a), results in formation of the corresponding amide 220 [Eq. (51)].

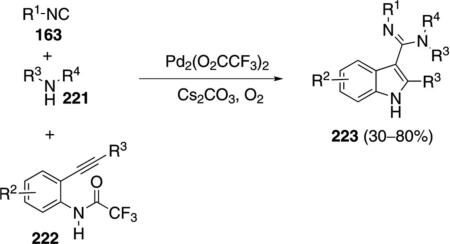

|

(52) |

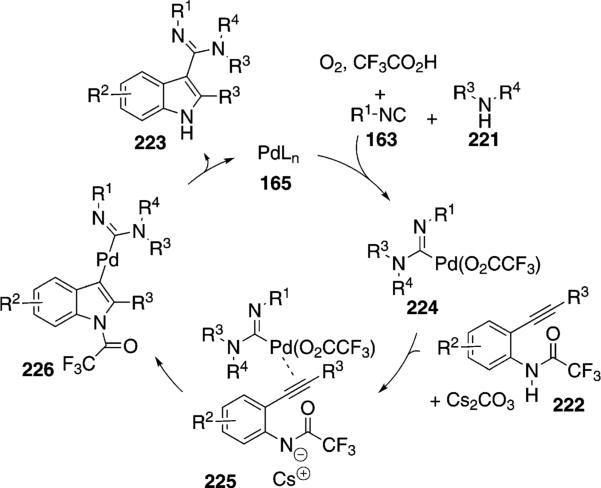

Palladium trifluoroacetate catalyzes a related condensation of isonitriles 163 with 2-alkynylamides 222 and an amine 221 to afford indoles 223 [Eq. (52)].[87] Tertiary isonitriles react best with the isonitriles cyclohexyl isocyanide and pentyl isonitrile providing the corresponding indoles in 39–45% yield. The reaction tolerates electron-withdrawing and electron-donating substituents in the benzene ring and aliphatic and aromatic acetylenic substituents.

Mechanistically, the reaction is initiated through an oxidative condensation of palladium with the isonitrile 163 and amine 221 to afford 224 (Scheme 29). Coordination of palladium complex 224 to the acetylene of 222 activates the system toward cyclization, perhaps through the deprotonated amide 225. Reductive elimination from the resulting indole 226, accompanied by loss of the trifluoroacetamide, affords 223 and releases zerovalent palladium species 165.

Scheme 29.

Palladium-catalyzed indole formation.

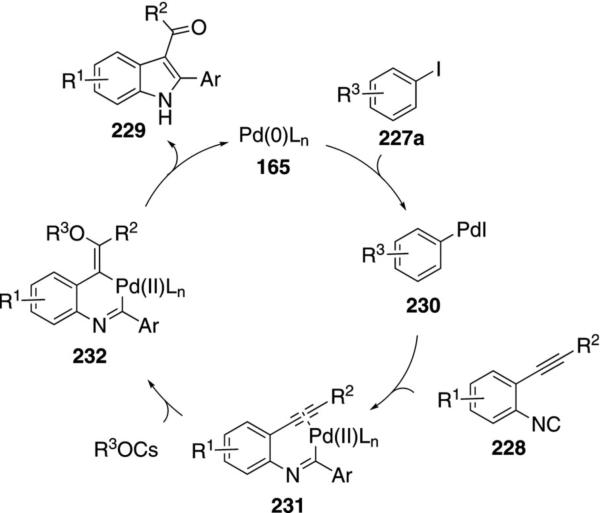

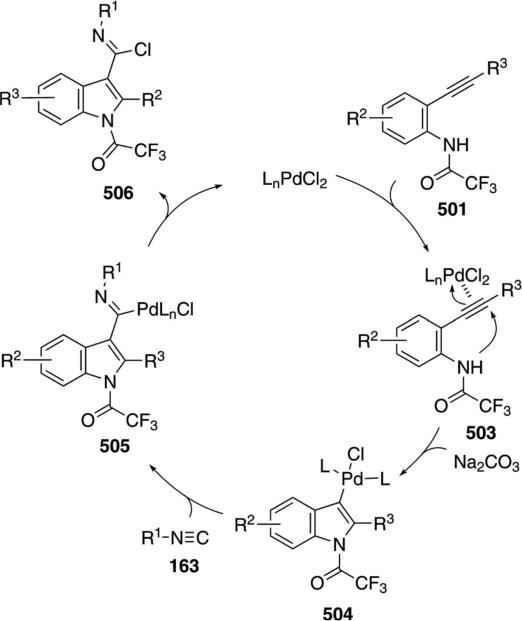

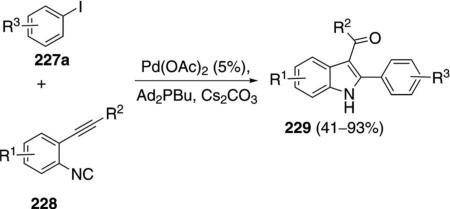

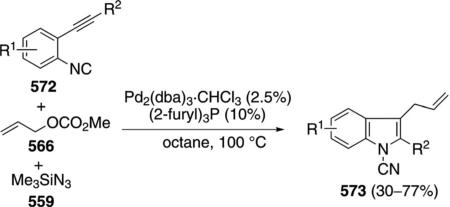

Catalytic palladium acetate condenses ortho-acetylenic isonitriles 228 with aryl iodides 227a to afford substituted indoles 229 [Eq. (53)].[88] Electron-donating groups and chlorine substituents within the aryl iodide 227a, have minimal effects on the reaction. Electron-withdrawing substituents cause a distinct decrease in the yield of the indole 229. Aryl iodides

|

(53) |

bearing nucleophilic ortho subtituents react further with the ketone to afford tetracyclic indoles.

The catalytic cycle is initiated through insertion of zerovalent palladium into the aryl iodide 227a to form 230. Insertion of the isonitrile 228 into the palladium-carbon bond of 230 generates 231 that is poised for cyclization (Scheme 30). Activation of the pendant alkyne by palladium complexation facilitates nucleophilic attack by hydroxide, acetate, or carbonate to afford 232. Reductive elimination from 232 and hydrolysis or enolization leads to the indole 229 and regenerates zerovalent palladium 165.

Scheme 30.

Palladium-catalyzed synthesis of indoles.

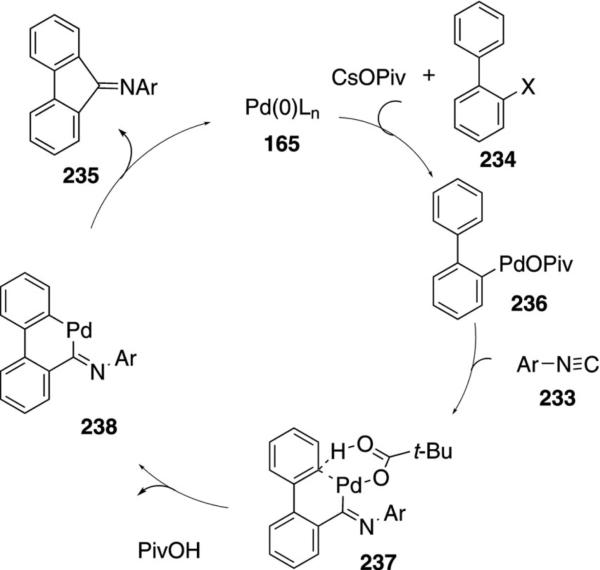

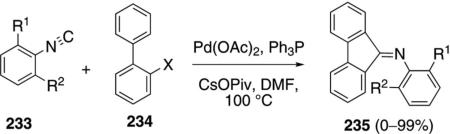

The combination of Pd(OAc)2, Ph3P, and CsOPiv catalyzes the coupling of 2,6-disubstituted phenyl isocyanides 233 with 2-halobiaryls 234 to afford iminofulvenes 235 [Eq. (54)].[89] The optimal isonitrile proved to be 2,6-diisopropylphenyl isocyanide (233); aliphatic isonitriles are unsuitable reaction partners. A wide range of biaryls, electron-deficient pyridines,

|

(54) |

and similar substrates, effectively participate in the coupling. The reaction exhibits good functional group tolerance.

Labelling studies demonstrate that the turnover-limiting step of the reaction is C–H insertion (Scheme 31). Initial C–X insertion of zerovalent palladium into 234 affords 236. Isonitrile insertion into 236 affords 237 bearing the pivolate ligand. Palladation of the aromatic ring may proceed through concerted metallation–deprotonation (237) or electrophilic addition; the precise mechanism is not known. Subsequent reductive elimination from the iminopalladium species 238 affords imine 235 and regenerates the catalyst.

Scheme 31.

Palladium-catalyzed isonitrile–insertion–C–H activation route to iminofulvenes.

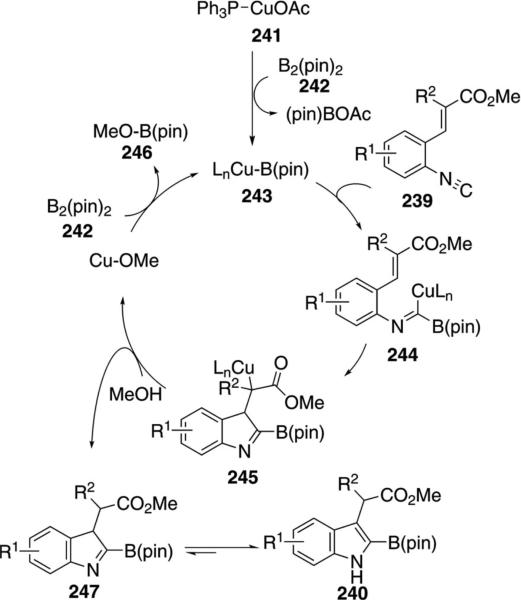

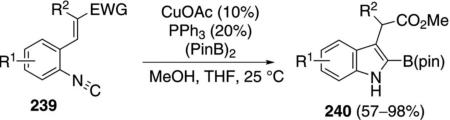

Borylindoles 240, valuable substrates for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling, were prepared through a copper-catalyzed borylation–cyclization of 2-alkenylphenyl isonitrile 239 [Eq. (55)].[90] The coupling proceeds at room temperature and, after filtration, the boryl imine can be used directly in a subsequent Suzuki–Miyaura coupling.

|

(55) |

The coupling is initiated by reaction of (BPin)2 (242) with the copper-phosphine complex 241 to form the active copper catalyst 243 (Scheme 32). Insertion of isonitrile 239 into the copper-boron bond of 243 leads to the organocopper-containing imine 244 triggering an internal 1,4-conjugate addition 244→245. Protonation of 245 by methanol releases CuOMe and 247 that then tautomerizes to indole 240. CuOMe then reacts readily with (PinB)2 to regenerate the catalyst 243.

Scheme 32.

Copper-catalyzed borylation affording borylindoles.

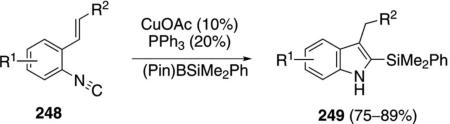

An analogous silylation sequence employs isonitrile 248, the same catalyst system, and a silylboronate to generate silylindoles 249 [Eq. (56)].[90] An electron-withdrawing

|

(56) |

olefinic substituent R2 is required: an ester, an amide, or a nitrile. The donor and acceptor groups OMe, Me and MeO2C groups are tolerated as substituents R1 in the aromatic ring.

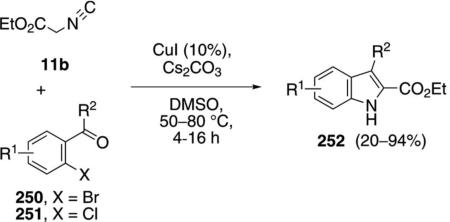

Copper iodide catalyzes the condensation of ethyl isocyanoacetate 11b and 2-haloaryl aldehydes or ketones 250 and 251 to afford indole-2-carboxylic acid esters 252 [Eq. (57)].[91] The aromatic ring tolerates

|

(57) |

diverse electronic substituents. Ketones react more efficiently than aldehydes.

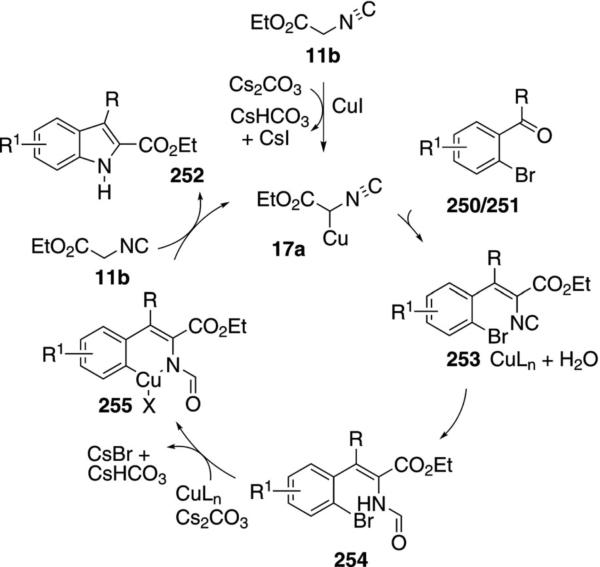

Although the mechanism has not been determined, the sequence likely involves a Knovenagel condensation of the cuprated isonitrile 17a with the carbonyl halide 250/251 (Scheme 33). Hydrolysis of the unsaturated isonitrile 253 by the liberated water then generates the corresponding formamide 254. Copper-catalyzed cyclization 254→255, reductive elimination, deformylation, and protonation from ethyl isocyanoacetate (11b) complete the catalytic cycle.

Scheme 33.

Copper-catalyzed indole formation.

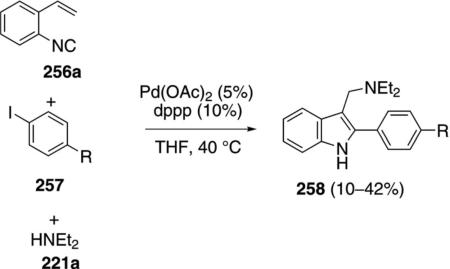

Palladium acetate catalyzes the synthesis of 2,3-substituted indoles 258 from ortho-alkenylphenyl isonitrile 256a, aryl iodides 257, and diethylamine 221a [Eq. (58)]. Although the yields are modest, the isonitrile

|

(58) |

tolerates diverse electronic substituents and the reaction assembles a functionalized indole in a single step.[92]

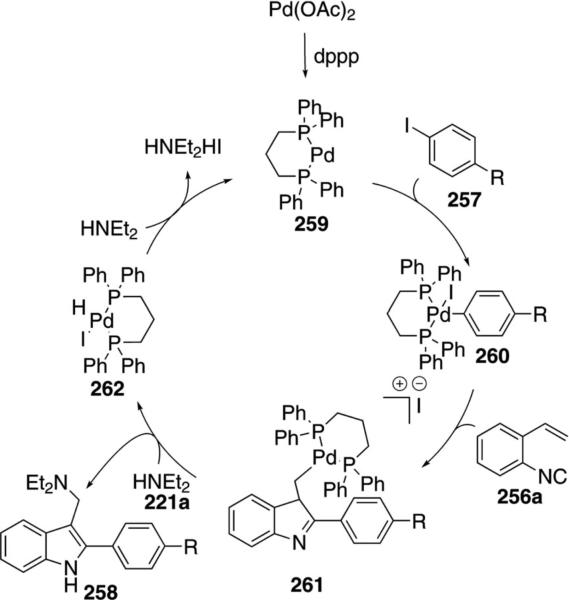

Mechanistically, insertion of the palladium catalyst 259 into the aryl iodide 257 gives 260 (Scheme 34). Complex 260 inserts isonitrile 256a with the palladium then adding onto the pendant olefin to give 261. Nucleophilic attack of diethylamine onto the palladium complex followed by reductive elimination and tautomerization gives the indole 258 and the palladium hydride complex 262. Base-induced reductive elimination of 262 by diethylamine regenerates the palladium catalyst 259.

Scheme 34.

Palladium-catalyzed synthesis of indoles.

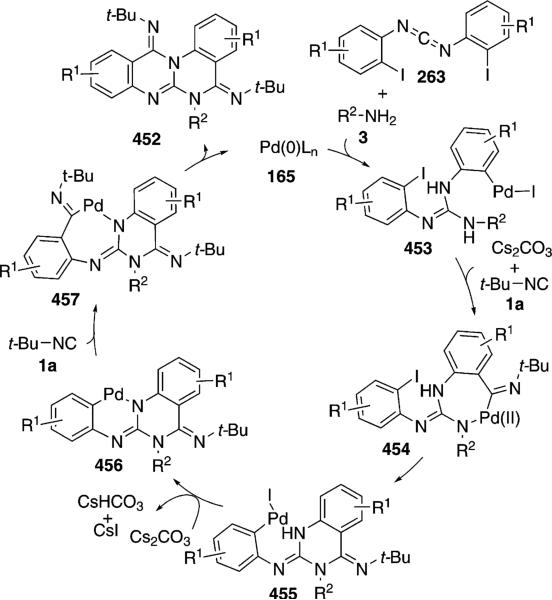

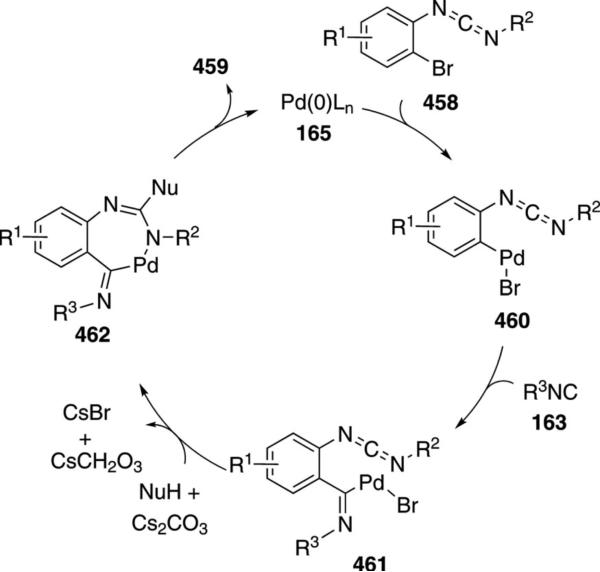

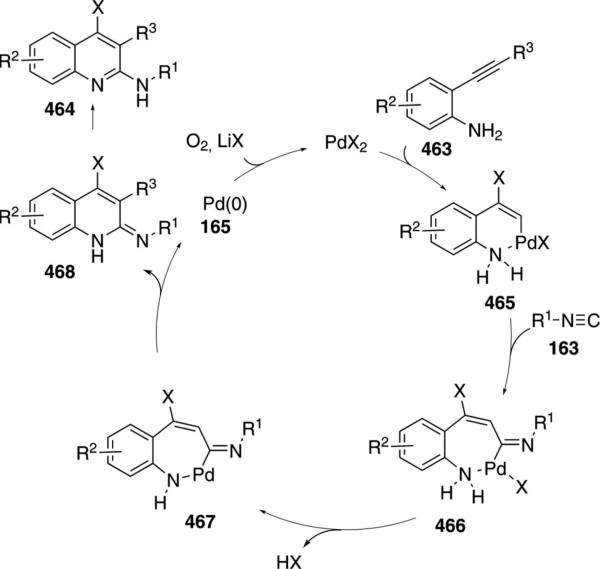

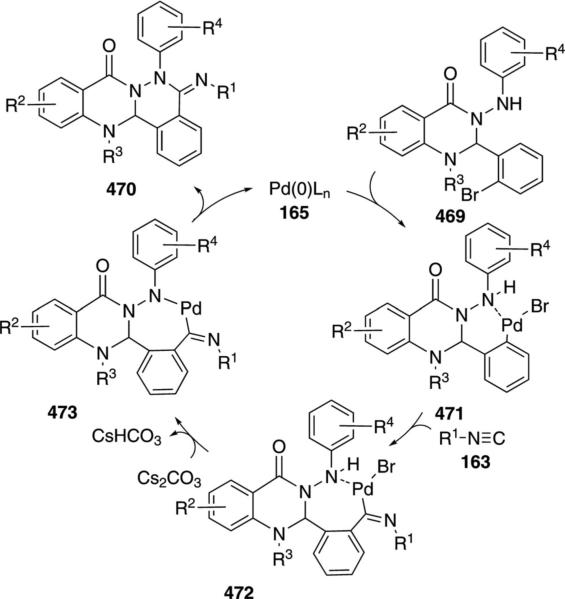

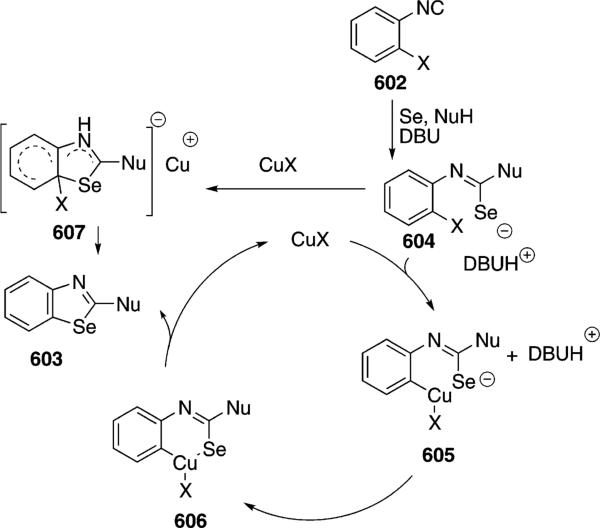

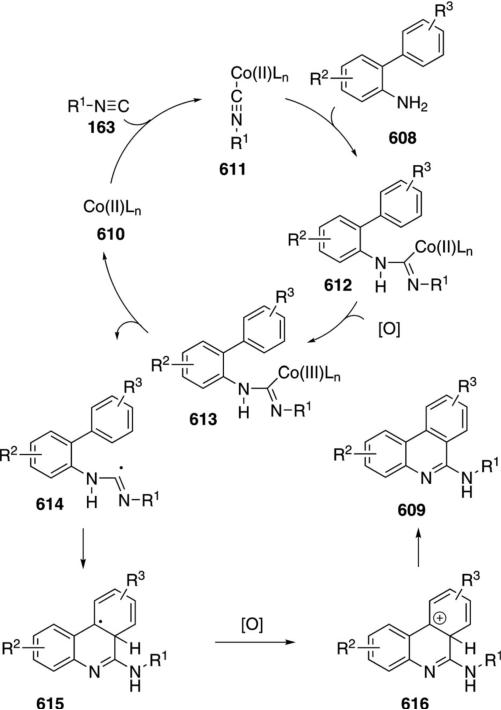

4 Condensations Affording Imidazoles

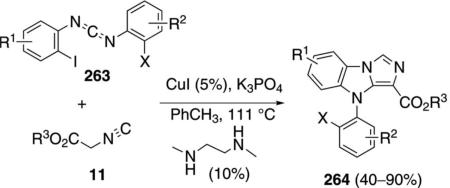

CuI catalyzes the condensation of isocyanoacetates 11 with carbodiimides 263 to form benzoimidazo[1,5-a]imidazoles 264 [Eq. (59)].[93] The condensation is

|

(59) |

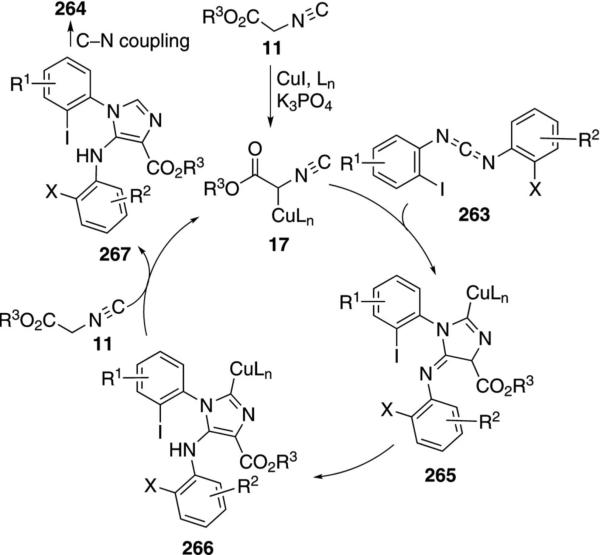

formally a [3+2]cycloaddition followed by a copper-catalyzed amination with the aryl iodide. A variety of amine ligands was screened with N1,N2-dimethylethane-1,2-diamine proving optimal. An isocyano ester is required for good yields; the sulfonyl isonitrile, TosMIC, provides 264 in only 40% yield. Me, Cl, I or H substituents are tolerated in the diimide 263.

Activation of isonitrile 11 by the CuI-amine catalyst forms the metallated isonitrile 17 (Scheme 35). A formal [3+2]cycloaddition of 17 with the diimide 263 generates 265, although a stepwise attack of 17 onto the C=N bond, followed by cyclization, may be more likely because the process directly parallels related reactions of imines. Tautomerization of 265 to 266, followed by a copper-assisted protonation by 11 yields 267 and regenerates the cuprated isonitrile 17. Copper-catalyzed intramolecular C–N coupling[94] of 267 leads to the benzoimidazo[1,5-a] imidazole 264.

Scheme 35.

Copper-catalyzed bis-cyclization of carbodiimides.

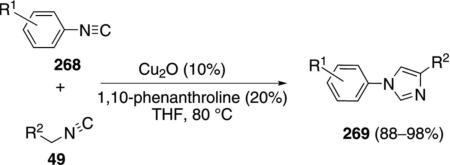

The first cross-condensation of isonitriles to form imidazoles was discovered during an attempted synthesis of pyrroles [Eq. (60)].[95] The Cu2O-catalyzed

|

(60) |

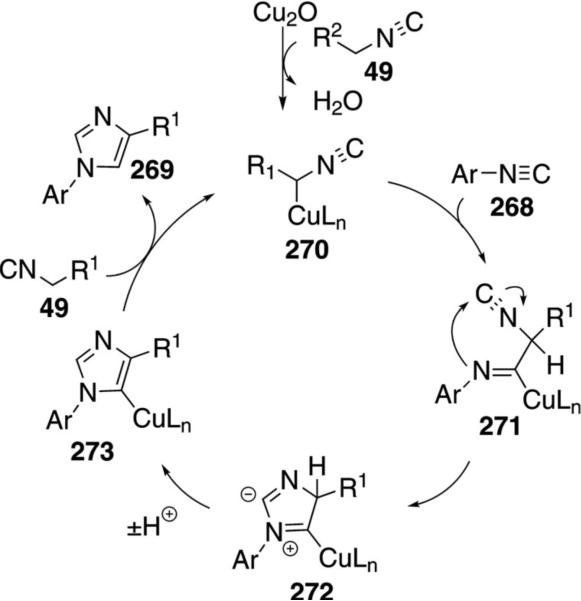

reaction effectively condenses a variety of electron-rich and electron-deficient aryl isonitriles 268 with isonitriles 49 bearing an adjacent electron-withdrawing group R2. The reaction proceeds at 80°C in THF. Aliphatic isonitriles do not participate in the reaction.

Copper oxide activates the C–H bond of the isonitrile 49 to generate cuprated isonitrile 270 (Scheme 36). Nucleophilic addition of 270 onto aryl isonitrile 268 forms the copper imine 271 with subsequent attack of the aryl nitrogen onto the isonitrile carbon to give 272. Proton transfers transform 272 to imidazole 273. Protonation of the C–Cu bond of 273 by 49 yields the 1,4-disubstituted imidazole 269 and regenerates the true catalyst 270.

Scheme 36.

Copper-catalyzed synthesis of arylimidazoles.

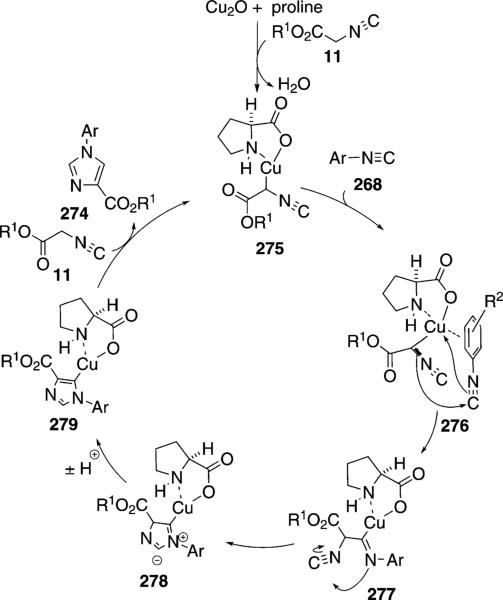

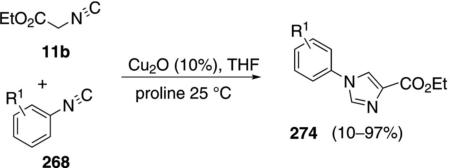

An almost identical cross-condensation of ethyl isocyanoacetate (11b) with aryl isonitriles 268 was performed with catalytic Cu2O and proline to form N-arylimidazoles 274 [Eq. (61)].[96] The isonitriles were

|

(61) |

prepared from the corresponding formamides, dehydrated with POCl3 and Et3N, and used without purification. Proline was found to be the best ligand when the reaction was performed at room temperature, although 1,10-phenanthroline is equally efficient if the reaction is performed in refluxing THF. The reaction tolerates electron-withdrawing and electron-rich substituents in the aromatic ring. Considerable functional group tolerance was demonstrated through reactions of acetylated isonitrile-containing glycosides.

Copper(I) oxide is a weak base that combines with proline and isocyanoacetate 11b to form complex 275 (Scheme 37). Complex 275 chelates to the isonitrile 268 to form 276 with a π interaction that facilitates an intramolecular nucleophilic attack to yield 277. The precedented complexation explains why cross-condensation is favored over homodimerization. Intramolecular attack within isonitrile 277 affords zwitterion 278 from which subsequent proton transfers afford 279. Coordination of isocyanoacetate 11, and protonation of the copper-carbon bond, closes the catalytic cycle and releases the N-arylimidazole 274.

Scheme 37.

Copper–proline-catalyzed imidazole formation.

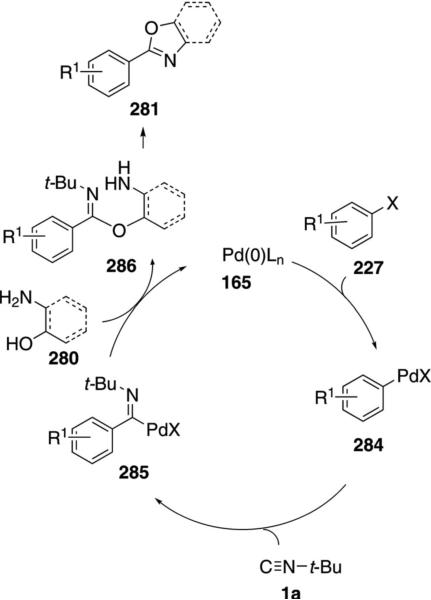

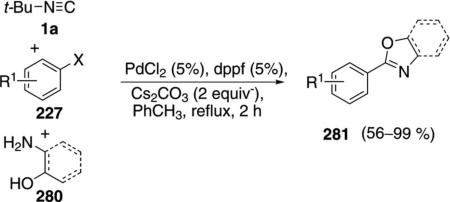

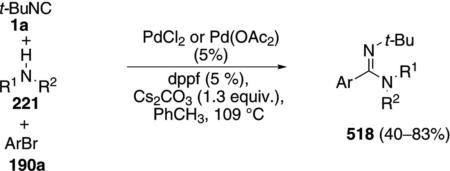

Various oxazoles and benzoxazoles 281 are readily assembled through a three-component coupling of aryl iodides and bromides 227 with tert-butyl isonitrile (1a) and an amino alcohol or ortho-aminophenol 280 [Eq. (62)].[97] Only the isonitrile carbon is incorporated

|

(62) |

into the oxazoline 281, with aminoethanol acting to displace tert-butylamine. The coupling is equally efficient with electron-rich and electron-deficient aryl bromides, iodides, and triflates.

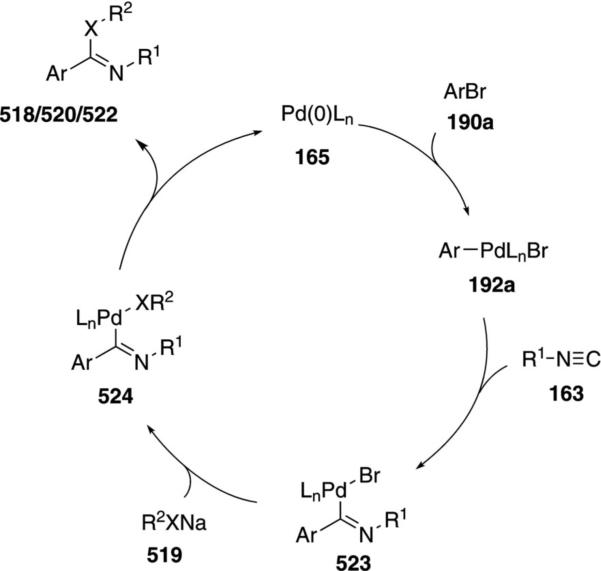

The same PdCl2-dppf combination allows the conversion of diamines 282 to imidazoles 283 [Eq (63)].[98] In some cases the combination of PdCl2 and dppp is superior to PdCl2 and dppf. Extending the reaction to 1,3-diaminopropane affords a tetrahydropyrimidine in 95% yield.

The two reactions involve essentially the same mechanism. Palladium oxidatively adds to the aryl halide 227 to generate the aryl palladium halide 284 which then inserts tert-butyl isonitrile (1a) to yield 285 (Scheme 38). Attack of aminoethanol on 285 affords 286 and releases the catalyst. The amidine 286

|

(63) |

suffers internal cyclization with loss of tert-butylamine to provide the oxazoline 281. Aminophenols and diamines react through an analogous sequence.

Scheme 38.

Isonitrile insertion route to oxazolines.

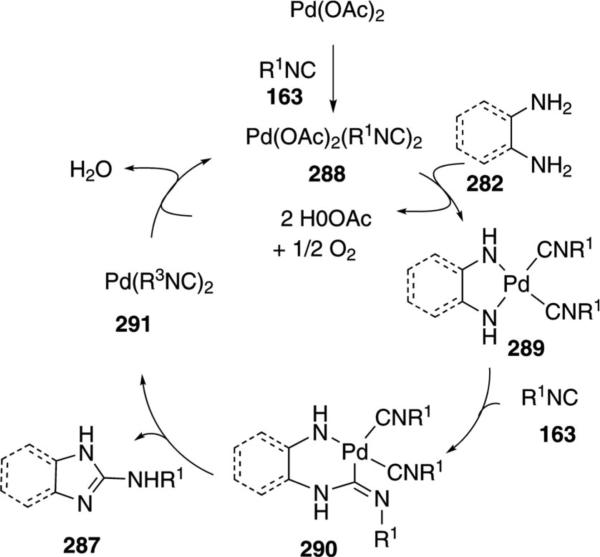

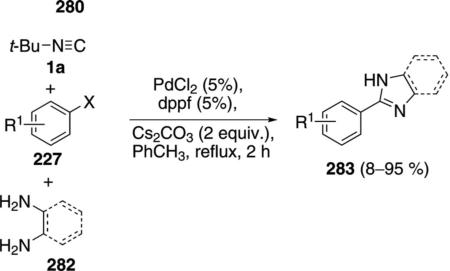

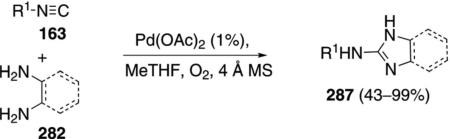

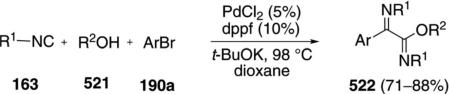

Pd(OAc)2 in 2-methyltetrahydrofuran catalyzes the condensation of isonitriles 163 with ortho-phenylenediamines 282, and similar bis-nucleophiles, to afford 2-aminobenzimidazole 287 [Eq. (64)].[99] The

|

(64) |

Pd(OAc)2 system has wide substrate scope both in the diamine and in allowing condensations with primary, secondary and tertiary isonitriles. In some instances, diamines bearing strong electron-withdrawing groups require higher catalyst loadings for complete conversion.

Palladium acetate is proposed to react with isonitrile 163 to form the active catalyst 288 (Scheme 39). Reaction of the diamine 282 with 288 affords 289 which suffers isonitrile insertion from the coordinated isonitrile. Additional isonitrile then complexes the open coordination site. Reductive elimination from 290 releases the benzimidazole 287 with concomitant formation of the zerovalent palladium complex 291. Reoxidation of 291 with molecular oxygen regenerates the catalyst and releases water.

Scheme 39.

Palladium-catalyzed synthesis of 2-aminobenzimidazoles.

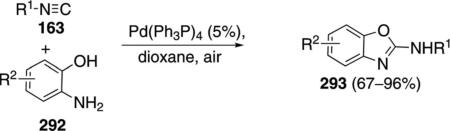

Tetrakis(triphenylphospine)palladium catalyzes the condensation of several isonitriles 163 with ortho-aminophenols 292 to generate 2-aminobenzoxazoles 293 [Eq. (65)].[100] Electron-rich ortho-aminophenols 292

|

(65) |

react smoothly whereas aromatics with electron-withdrawing groups require higher temperatures and longer reaction times. Primary, secondary, and tertiary isonitriles react equally well. Ethyl isocyanoacetate (11b) was the only substrate reported not to react.

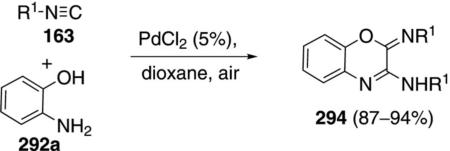

Switching the catalyst from Pd(Ph3P)4 to PdCl2 redirects the isonitrile–ortho-aminophenol condensation to afford 3-aminobenzoxazines 294 [Eq. (66)].[100] The double insertion process tolerates primary, secondary, and tertiary isonitriles.

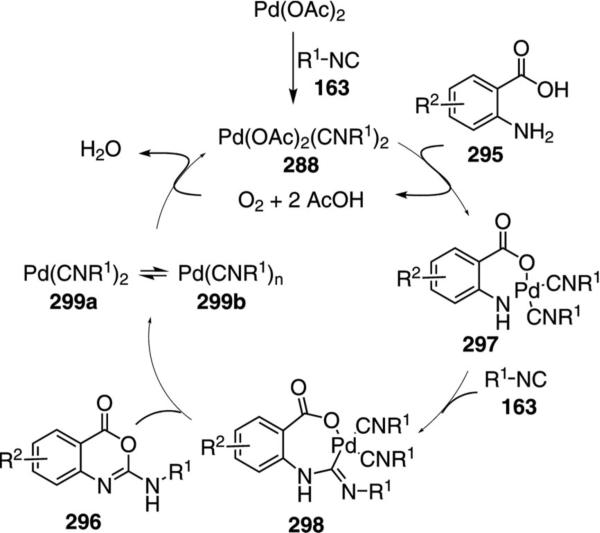

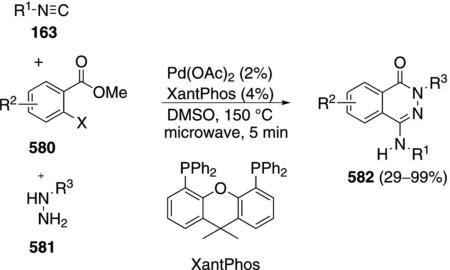

Palladium acetate catalyzes the reaction of isonitriles 163 with anthranilic acids 295 to afford bioactive

|

(66) |

|

(67) |

2-aminobenzoxazinones 296 [Eq. (67)].[101] Primary, secondary, and tertiary isonitriles participate in the reaction although the yield with butyl isonitrile was distinctly reduced. The condensation tolerates electronically diverse substituents in the anthranilic acid without adversely affecting the reaction efficiency.

The excellent ligation of isonitriles is thought to result in the conversion of palladium acetate into complex 288 incorporating two isonitrile groups. Condensation of 288 with anthranilic acid 295 leads to 297 which undergoes migratory insertion of an isonitrile ligand followed by ligation of another isonitrile to the vacant coordination site (Scheme 40). Reductive elimination from 298 releases 296 and a palladium(0) complex 299 that is reoxidized to 288.

Scheme 40.

Palladium-catalyzed synthesis of 2-aminobenzoxazinones.

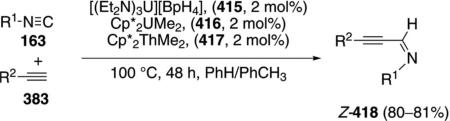

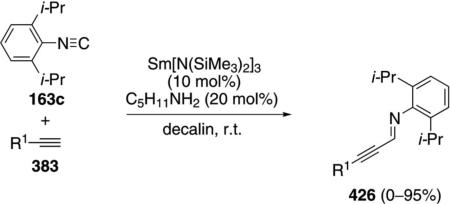

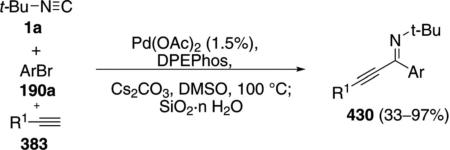

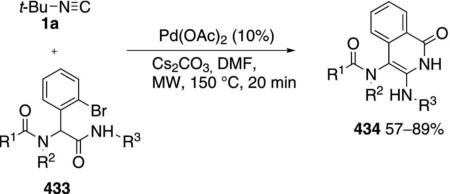

5 Condensations Affording Imines

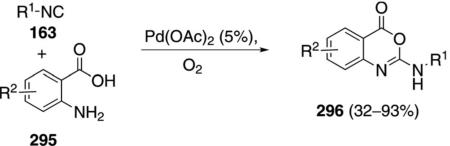

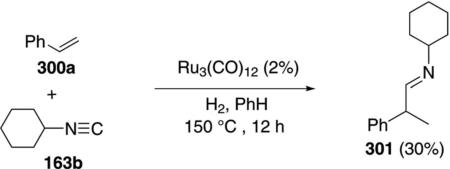

Over twenty years ago styrene (300a) was hydroiminoformylated with cyclohexyl isonitrile (163b) [Eq. (68)].[102]

|

(68) |

Ru3(CO)12 catalyzes the reaction, through an unknown mechanism, to afford imine 301 in a modest 30% yield. Although the reaction with pentene only gave 14% of the corresponding imine, the reaction seems ripe for development.

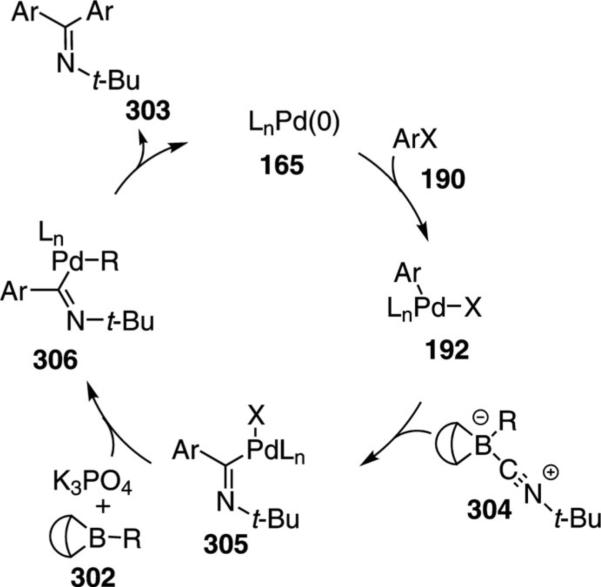

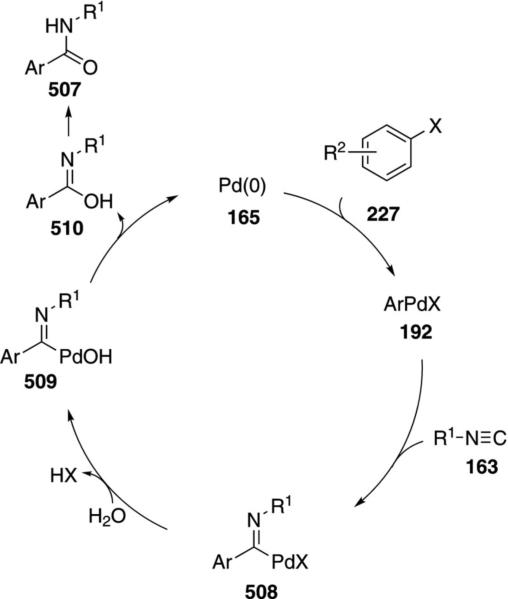

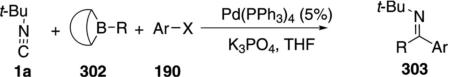

Pd(PPh3)4 catalyzes the iminocarbonylative cross-coupling reaction between tert-butyl isonitrile (1a), 9-alkyl-9-BBN 302 derivatives, and haloarenes 190 to afford imines 303 [Eq. (69)].[103] Strong bases and

|

(69) |

polar solvents lower the yield as do electron-withdrawing substituents on the iodoarene. The reaction is sensitive to the stoichiometry of the isonitrile and the 9-alkyl-9-BBN derivative; a 1:1 ratio being optimal. A boron–isonitrile complex appears to provide a reservoir of isonitrile while minimizing the concentration of free isonitrile.

Zerovalent palladium species 165 initiates the catalytic cycle through an insertion into the aryl halide 190 to generate 192 (Scheme 41). Delivery of the isonitrile via the borane complex 304 allows insertion into the aryl-palladium bond of 192 to form 305. Base activation of the free borane facilitates the alkyl transfer from boron to palladium 305→306. Reductive elimination from 306 releases the imine 303 and completes the catalytic cycle.

Scheme 41.

Palladium-catalyzed iminocarbonylative cross-coupling.

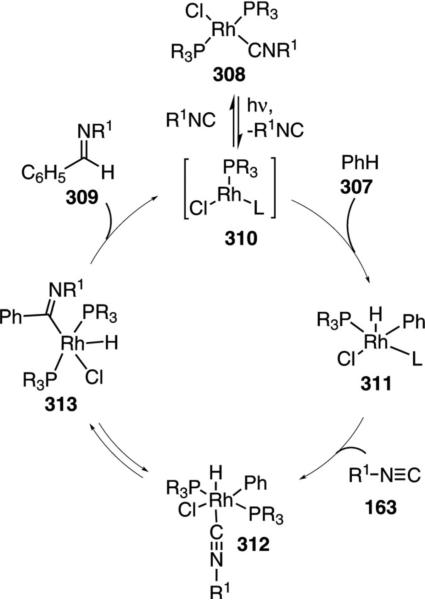

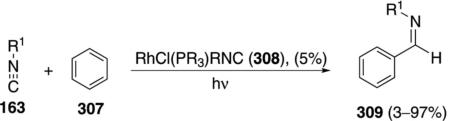

C–H bond insertion of isonitrile 163 into benzene (307) with RhCl(PR3)R1NC (308) affords iminobenzaldehyde 309 [Eq. (70)].[104] A mechanism-oriented

|

(70) |

study demonstrated the feasability of catalysis under UV irradiation, measuring conversion rather than isolated yield.

The precise mechanism for the C–H and isonitrile insertion is not clear. UV irradiation of 308 is thought to promote dissociation of either a phosphine or an isonitrile ligand to create the electrophilic rhodium complex 310 (Scheme 42). Insertion of 310 into benzene generates the complex 311 which coordinates isonitrile 163 and triggers an insertion of the ligated isonitrile group 312→313. Reductive elimination from 313 releases the benzaldimine 309 and the active catalyst 310. Excess isonitrile forms a bisphosphine–bisisonitrile rhodium complex which precipitates from solution. Under UV irradiation the complex is able to release sufficient amounts of a catalytically active species to promote the reaction.

Scheme 42.

Rhodium-catalyzed C–H isonitrile insertion.

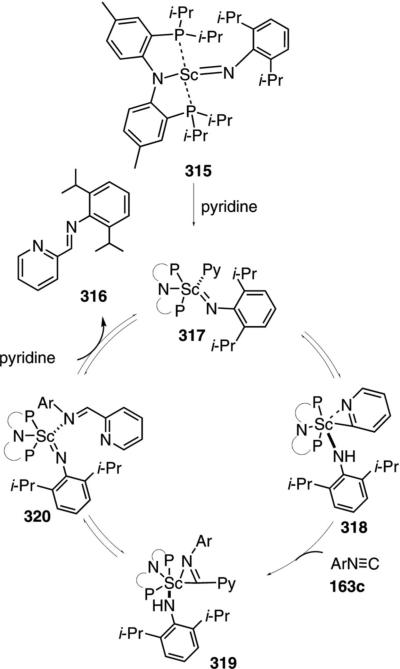

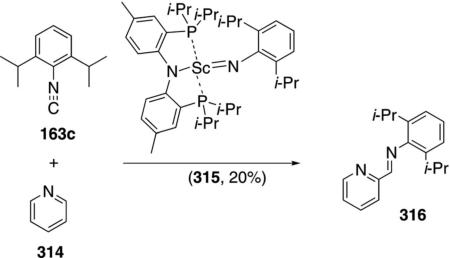

A scandium imide complex 315 catalyzes the C–H insertion into pyridine (314) and subsequent isonitrile

|

(71) |

insertion to form the imino-substituted pyridine 316 [Eq. (71)].[105] The catalytic reaction was not performed preparatively but gives complete conversion after 4 h. Only the hindered isonitrile 163c engages in catalysis; less hindered isonitriles bind irreversably to the catalyst.

Isolation of several scandium complexes supports the proposed catalytic cycle (Scheme 43). Complex 317, generated by addition of pyridine to 315, is the active form of the catalyst which undergoes C–H insertion to form 318. Insertion of the isonitrile 163c into the scandium-carbon bond of 318 generates 319; an intermediate that can be crystallized from solution (Scheme 43). Proton transfer within 319 affords tautomer 320 that releases the iminopyridine 316, binds additional pyridine, and regenerates the catalyst.

Scheme 43.

Scandium-catalyzed C–H and isonitrile insertion.

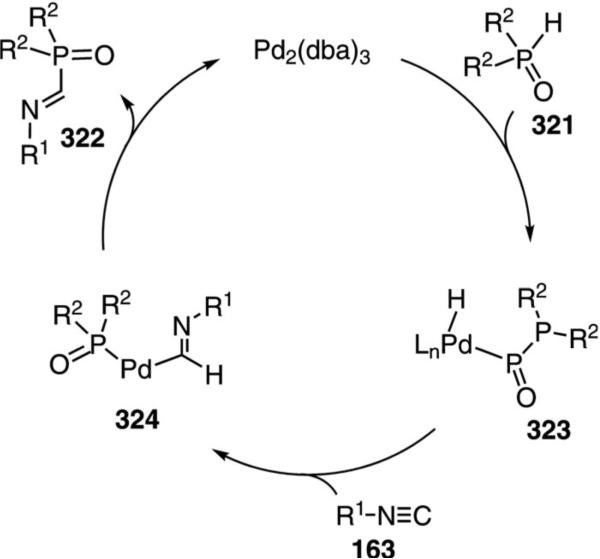

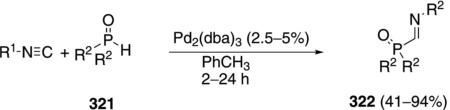

α-Iminophosphine oxides 322 are synthesized by the palladium-catalyzed insertion of isonitriles 163 into secondary phosphine oxides 321 [Eq. (72)].[106]

|

(72) |

Aromatic and aliphatic substituents on the isonitrile are tolerated, even with sterically hindered substrates. Both aliphatic and aromatic substituents are tolerated, but highly branched phosphines are unreactive.

An initial insertion of Pd2(dba)3 into the P–H bond of the phosphine oxide 321 is thought to initiate the catalytic cycle. The resulting hydropalladium complex 323 inserts isonitrile 163 into the Pd–H bond to form complex 324 (Scheme 44). Subsequent reductive elimination from 324 affords the α-iminophosphine oxide 322 and regenerates the palladium catalyst.

Scheme 44.

Palladium-catalyzed iminophosphine oxide formation.

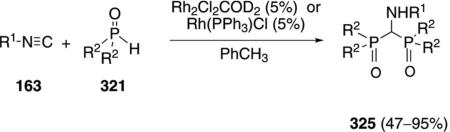

Several rhodium(I) complexes catalyze the condensation of isonitriles 163 with secondary phosphine oxides 321 to afford bisphosphinoyl(amino)methanes 325 [Eq. (73)].[106] Presumably the mechanism parallels that of the palladium-catalyzed sythesis of α-iminophosphine

|

(73) |

oxides [Scheme 44] but includes a second phosphine oxide insertion followed by an attack on the initially formed iminophosphine oxide 322.

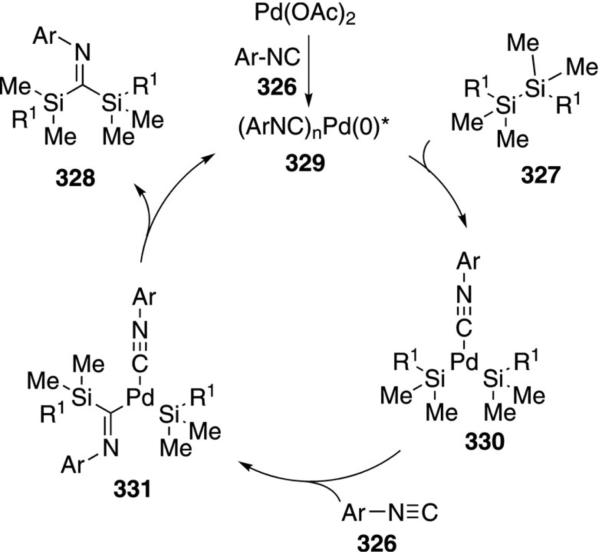

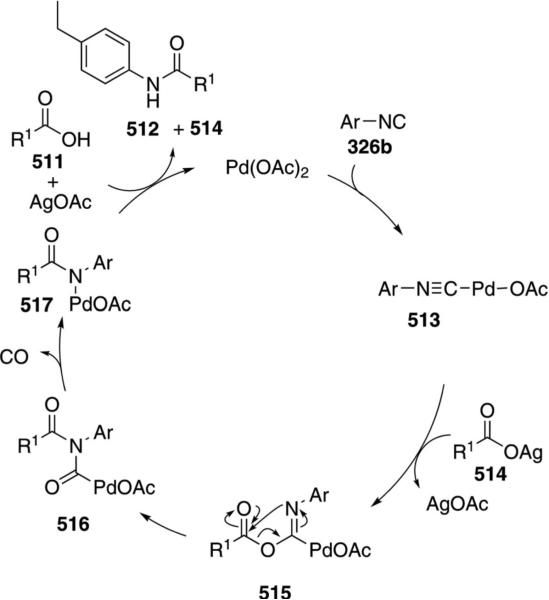

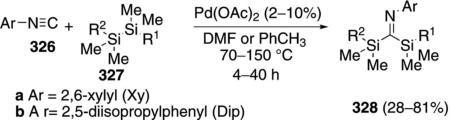

Palladium acetate catalyzes the insertion of aryl isonitriles 326 into the Si–Si bond of disilanes 327. [Eq. (74)].[107] The insertion was performed with a series of

|

(74) |

oligomeric silanes resulting in silylimines of varying molecular weights.

Mechanistically, the palladium(II) catalyst is reduced by isonitrile ligation[108] to the palladium(0) complex 329. Oxidative addition of 329 into the oligosilane 327 forms complex 330 (Scheme 45). Attack of the Pd–Si bond on the isonitrile 326 affords imine 331 which reductively eliminates to form 328 and regenerate the Pd(0) catalyst.

Scheme 45.

Palladium-catalyzed isonitrile insertion into Si–Si bonds.

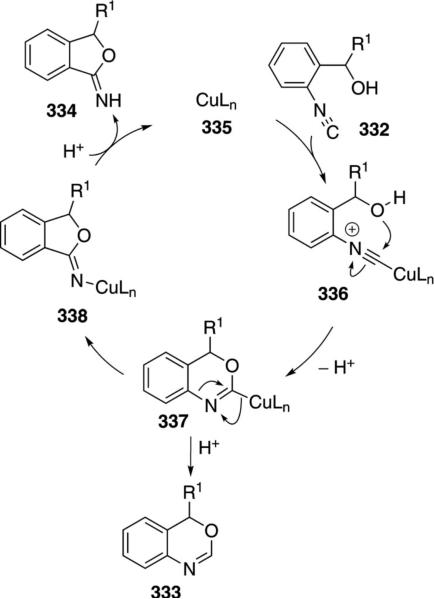

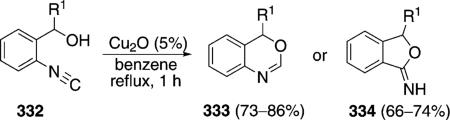

Copper oxide catalyzes the cyclization of isocyanobenzyl alcohols 332 [Eq. (75)].[109] 4H-3,1-Benzoxazines 333 are generated when the carbinol substituent R1 is 4-MeOC6H4, Ph, 4-Cl-C6H4, 4-pyridyl, or a tert-butyl group whereas tetrahydrofuranimines 334 are generated when the substituent R1 is a 2-(5-methylfural) or an isopropyl group. The reason for the changeover in product formation is unknown but is independant of the metal.

Copper oxide cyclizes isocyanobenzyl alcohols 332 by coordinating and activating the isonitrile carbon (Scheme 46).[110] Coordination of copper to the isonitrile 332 forms complex 336 which is activated toward

|

(75) |

internal attack by the hydroxy group. Cyclization and subsequent deprotonation affords 337. Protonation of 337 forms 333. Alternatively the benzoxazine 337 can undergo a formal 1,2-rearrangement to afford the isobenzofuranimine 338. Protonation of the iminocopper bond in 338 yields the tetrahydrofuranimine 334 and regenerates the copper catalyst.

Scheme 46.

Copper(I) oxide-catalyzed cyclization of isocyanobenzyl alcohols.

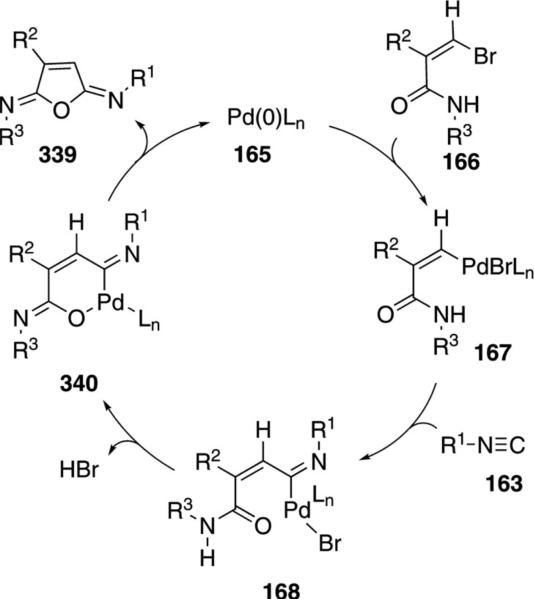

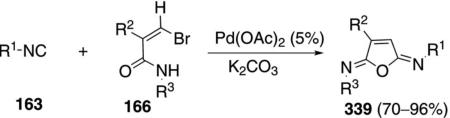

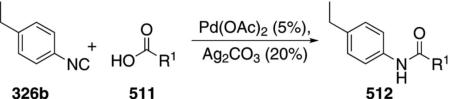

Aromatic and aliphatic isonitriles 163 are condensed with bromoacrylamides 166 and catalytic palladium acetate to form 2,5-diiminofurans 339 [Eq. (76)].[111] The reaction is essentially the same as a previously

|

(76) |

reported furan sequence in which the bromoacrylamide is generated in situ from a bromoalkyne (cf. Scheme 20). The difference lies in the use of K2CO3 rather than CsF which presumably redirects the reaction to 339 rather than an iminopyrrolidinone.

Mechanistically the reaction likely begins with an oxidative addition of the palladium(0) species (165) into the vinyl bromide to afford 167 (Scheme 47). Insertion of the isonitrile 163 into the palladium-carbon bond is followed by attack of the more nucleophilic oxygen onto the metal center of 168. Presumably the different ligands on palladium, compared to that in the iminopyrrolidinone reaction, are responsible for the preferential closure to 340 which reductively eliminates to afford 339.

Scheme 47.

Palladium-catalyzed synthesis of diiminofurans.

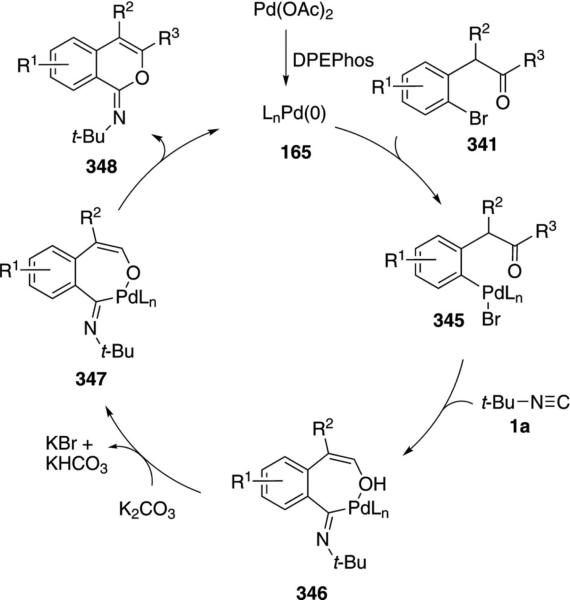

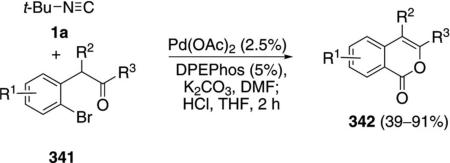

Palladium acetate, in combination with DPEPhos, catalyzes the condensation of tert-butyl isonitrile (1a) with ketone 341 to generate iminolactones that were hydrolyzed to the corresponding isocoumarins 342 [Eq. (77)].[112] Aromatic ketones (341, R3=Ar) work

|

(77) |

particularly well with minimal dependence on the electronic nature of the aromatic ring. NiCl2 (2.5%), DPPE, and K2CO3 catalyze the same condensation of tert-butyl isonitrile with ketones 341 to afford iminolactones (52–91%) with the advantage of employing a less expensive metal.[113]

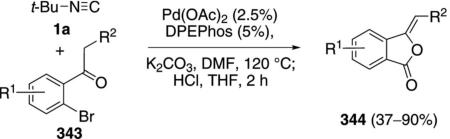

Palladium acetate with DPEPhos[112] and NiCl2, DPPE[113] both catalyze the condensation of the regioisomeric bromo ketones 343 with tert-butyl isonitrile to afford iminophthalides that were hydrolyzed to the corresponding phthalides 344 [Eq. (78)]. The ketone substituents R2 can be aliphatic or aromatic.

|

(78) |

Electron-rich aromatics are efficient substrates while electron-deficient aromatics are distinctly less effective substrates.

The mechanisms for the isocoumarin and phthalide syntheses are very similar. In the case of isocoumarins, oxidative addition of zerovalent palladium species 165 into the aryl bromide 341 affords complex 345 (Scheme 48). Sequential isonitrile coordination and insertion leads to the coordinated enol 346 that is activated toward deprotonation 346→347. Reductive elimination from 347 generates the iminocoumarin 348 that is hydrolyzed in a separate step to afford 342.

Scheme 48.

Palladium-catalyzed isocoumarin synthesis.

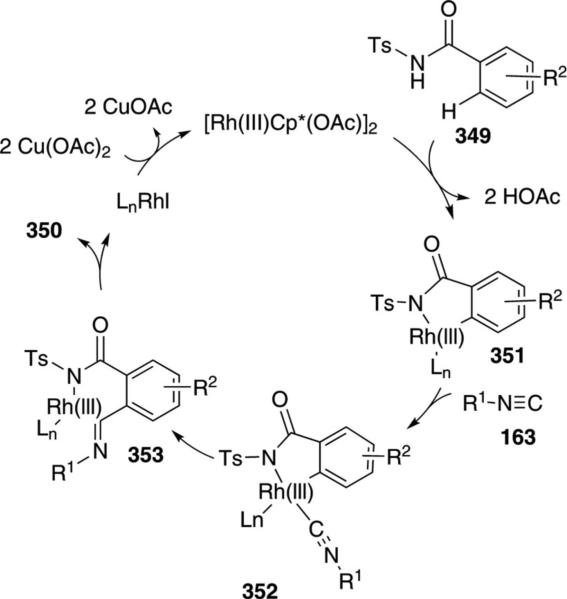

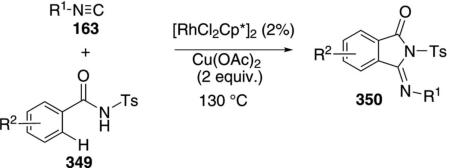

The rhodium complex [RhCl2Cp*]2 catalyzes the synthesis of 3-(imino)isoindolines 350 from isonitriles 163 and N-benzoylsulfonamides 349 [Eq. (79)].[114]

|

(79) |

C–H insertion adjacent to the sulfonamide is followed by isonitrile insertion and ring closure. The sulfon-amide is necessary for the reaction; less acidic benz-amides are unreactive. Cu(OAc)2 is required as an oxidant. Aliphatic and aromatic isonitriles react equally well but substituted aromatic isonitriles polymerize.

Several mechanistic experiments provide insight into the individual steps of the catalytic cycle. Rhodium insertion into the ortho-position of the benzamide is facile, implicating C–H insertion and cyclization as the first steps of the catalytic cycle (349→351, Scheme 49). Isonitrile complexation to rhodacycle 351 affords 352 as a prelude to insertion into the Rh–C bond (352→353). Reductive elimination from 353 generates the 3-(imino)isoindoline 350 and a rhodium(I) complex which is reoxidized to the rhodium(III) catalyst.

Scheme 49.

Rhodium-catalyzed (imino)-isonitrile synthesis.

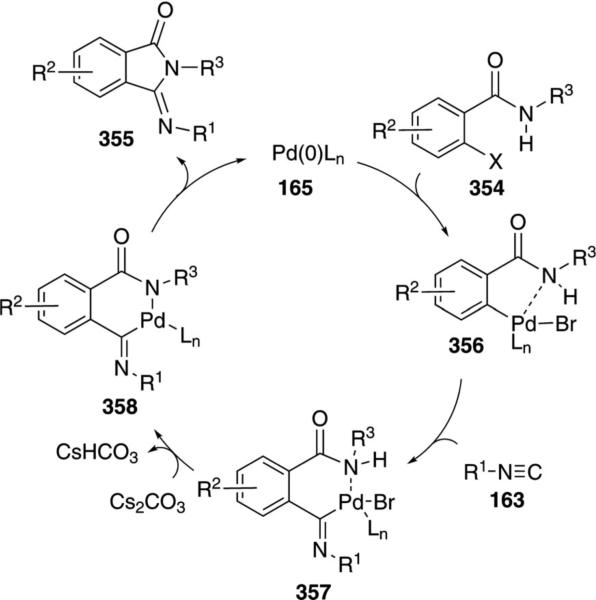

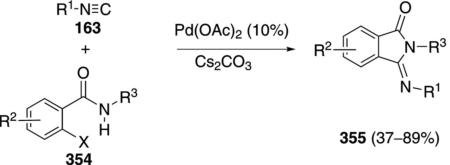

Tertiary isonitriles 163 react with o-haloamides 354 to form 3-(imino)isoindolines 355 in the presence of catalytic palladium acetate [Eq. (80)].[115] Several aromatic,

|

(80) |

benzylic, and cyclopropyl substituents are tolerated as substituents on the amide. Iodobenzamides react most efficiently (354 X=I). A chlorobenzamide affords the corresponding 3-(imino)isoindoline 355 less efficiently (44%) than the corresponding bromide.

Insertion of the benzamide 354 into zerovalent palladium species 165 affords 356 with an interaction between palladium and the amide nitrogen (Scheme 50). Isonitrile insertion into the palladium-carbon bond affords 357 that ejects HBr to afford 358. The elimination of HBr may occur at 356 prior to isonitrile insertion as the precise order of steps is currently unknown. Reductive elimination from 358 affords 355, releasing palladium for further catalysis.

Scheme 50.

Palladium-catalyzed (imino)-indolinone synthesis.

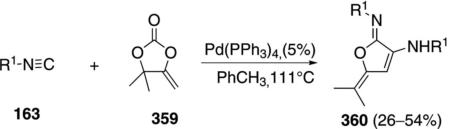

A related palladium-catalyzed double insertion of isonitrile 163 into carbonate 359 generates iminolactone 360 [Eq. (81)].[116] The mechanism is uncertain,

|

(81) |

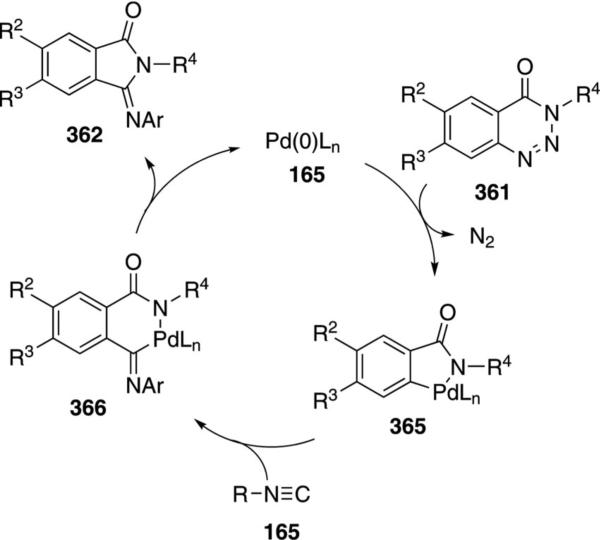

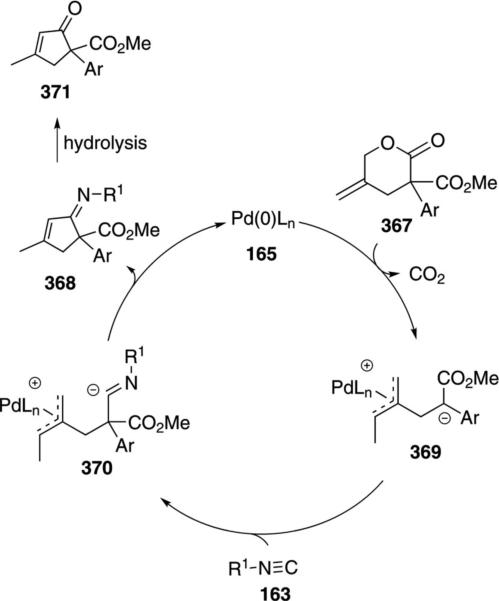

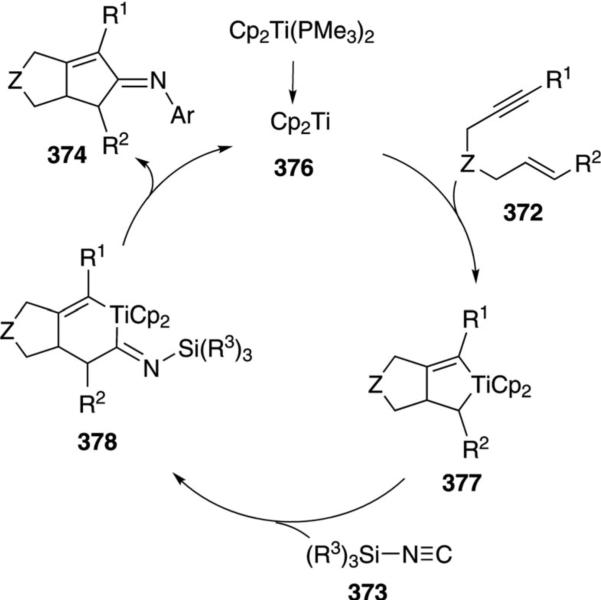

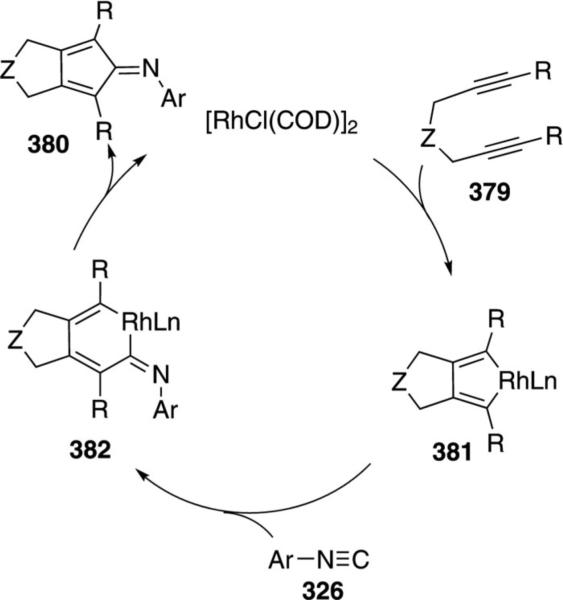

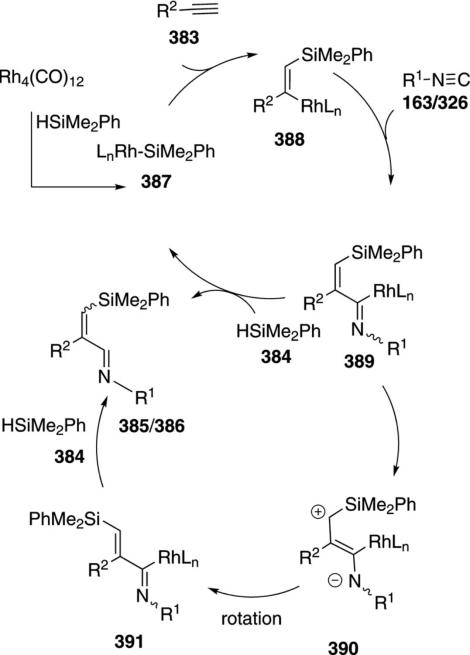

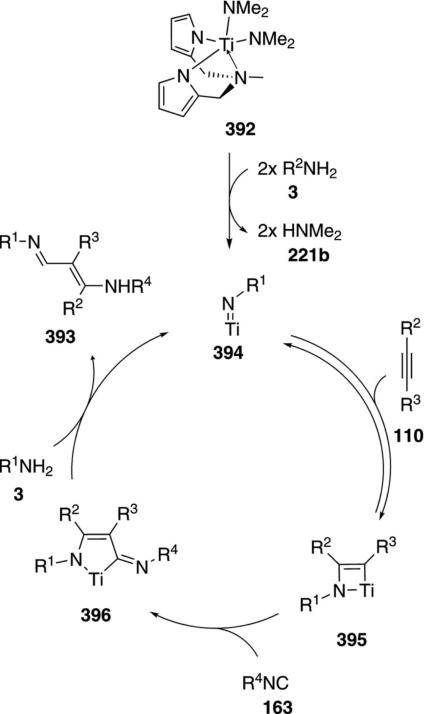

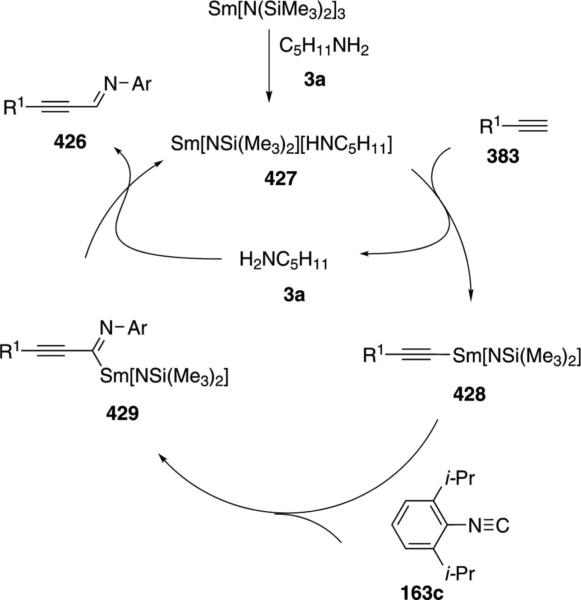

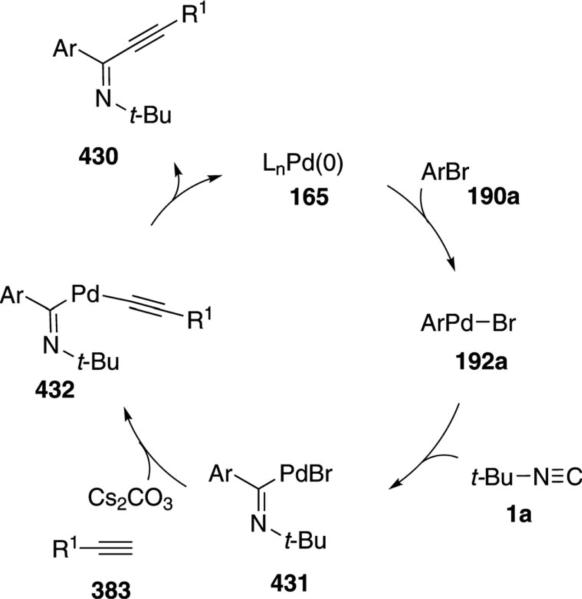

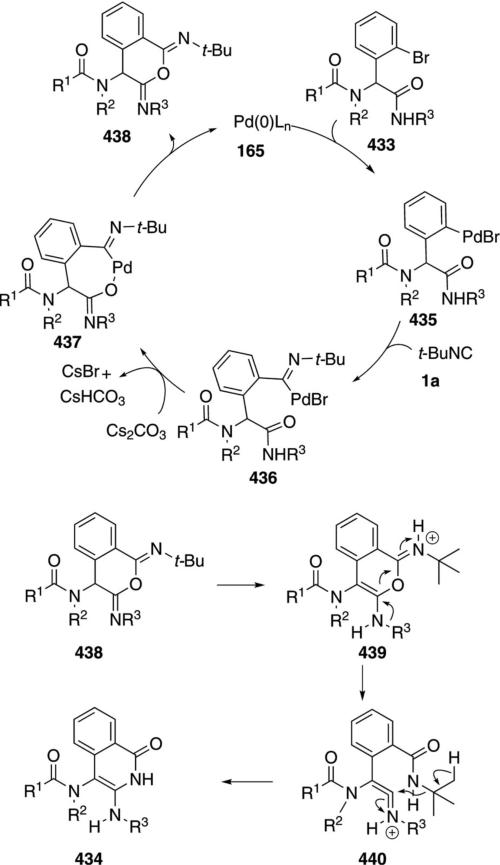

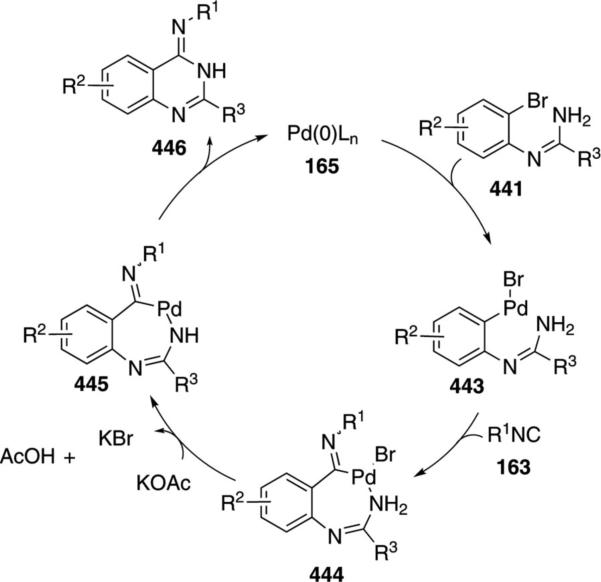

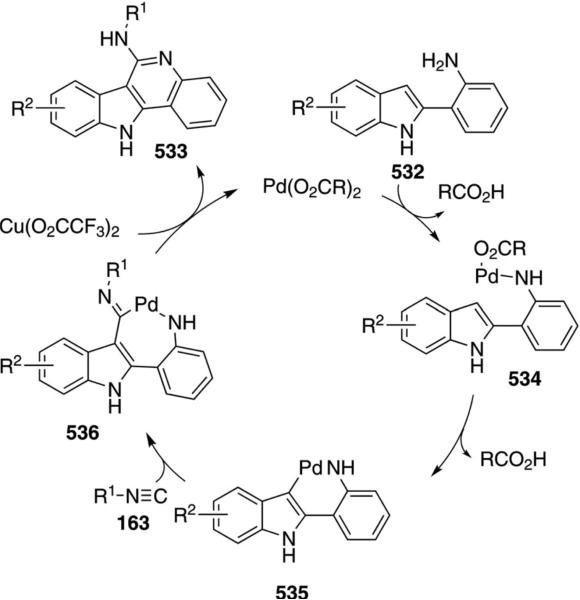

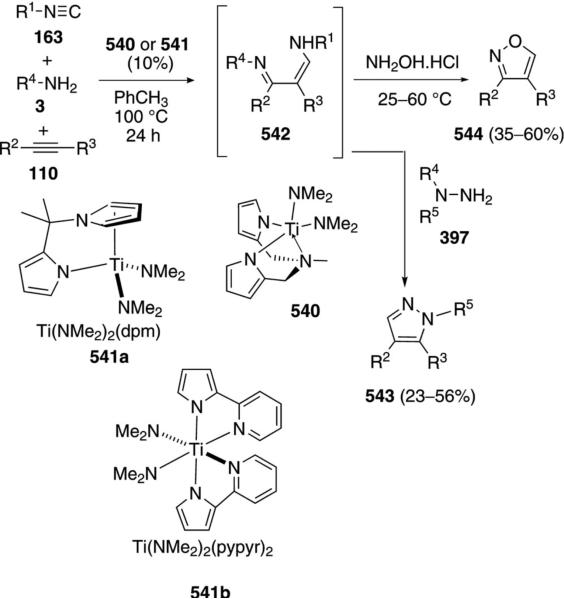

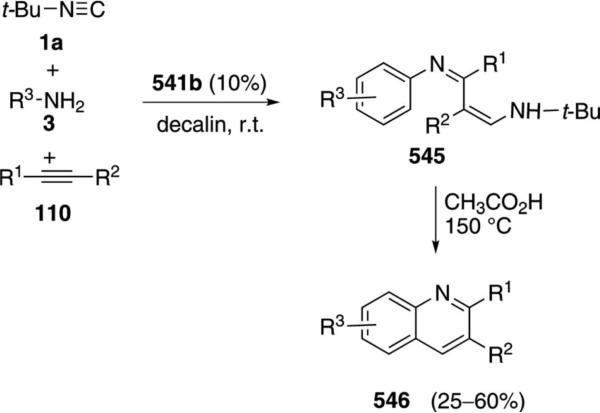

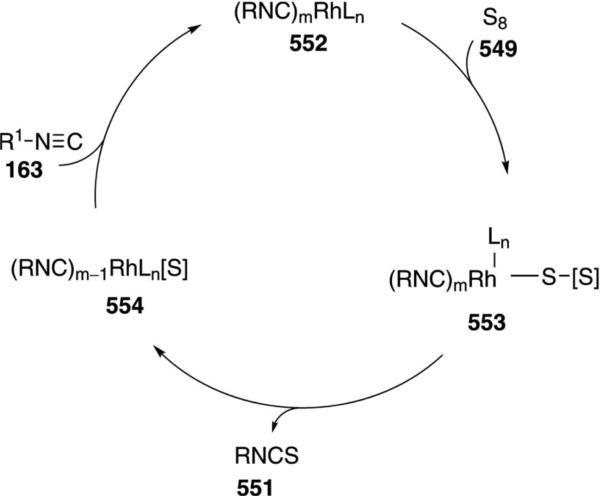

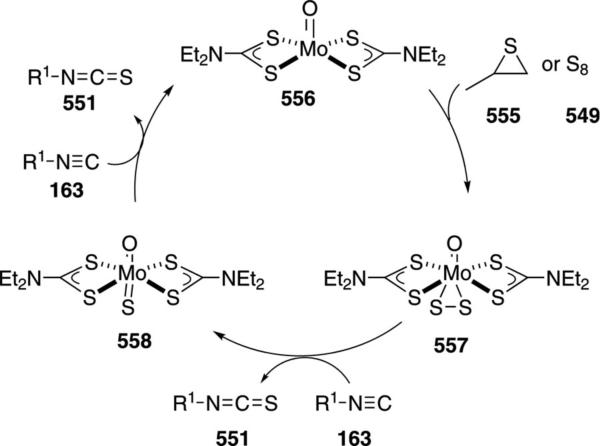

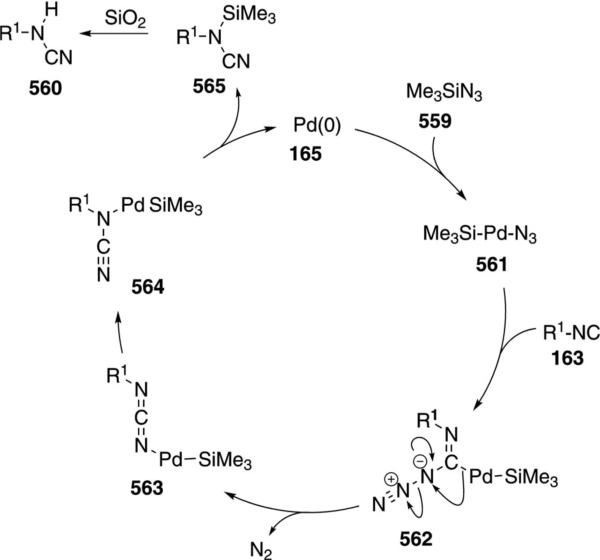

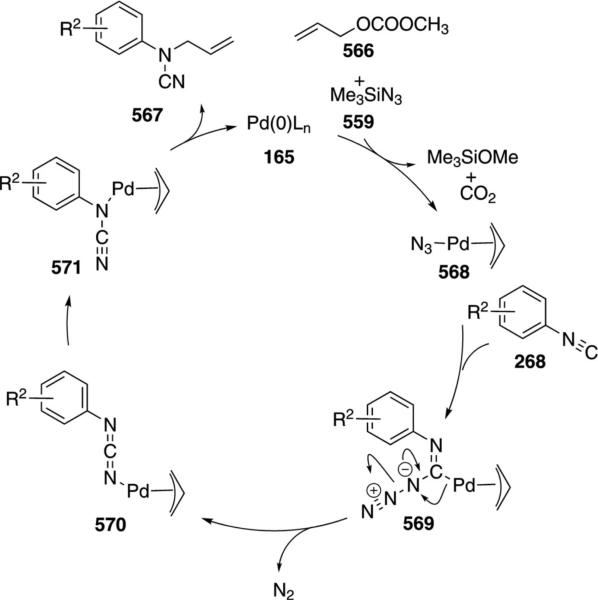

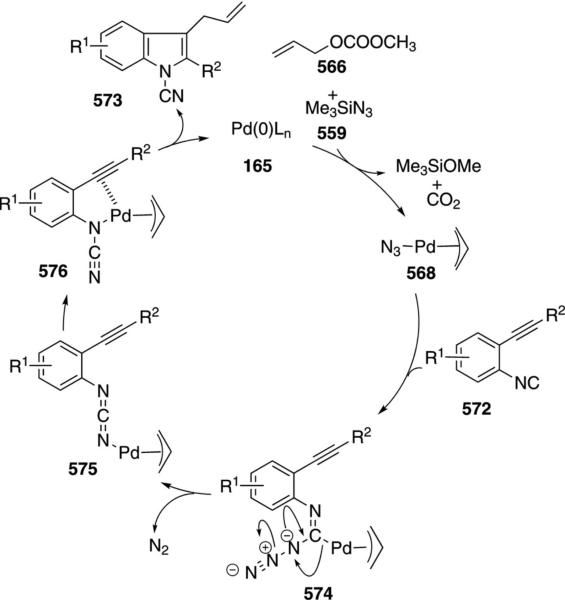

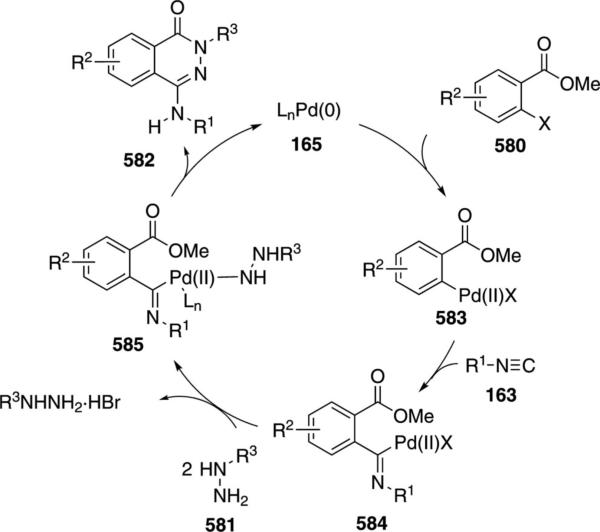

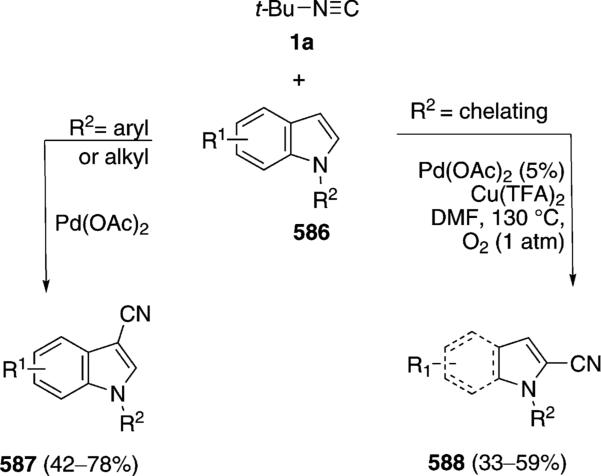

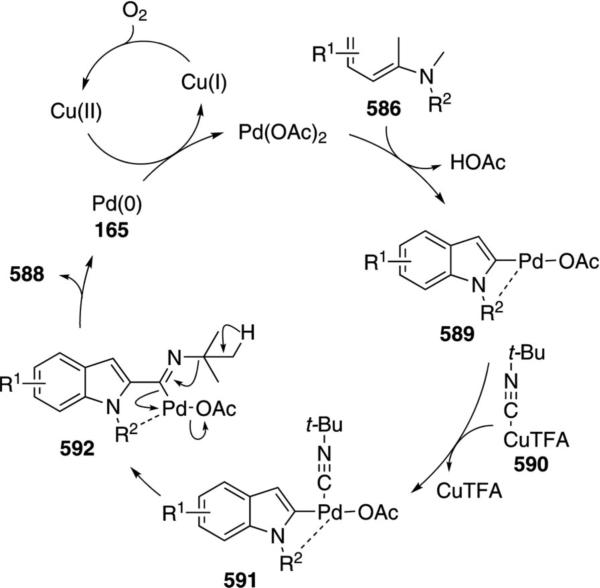

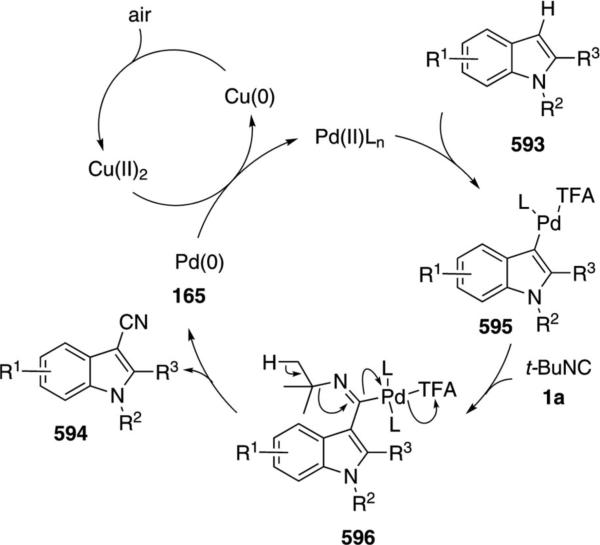

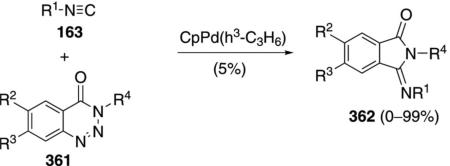

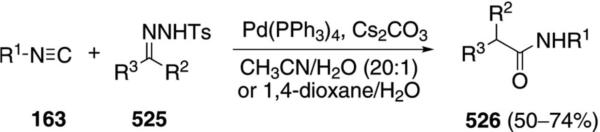

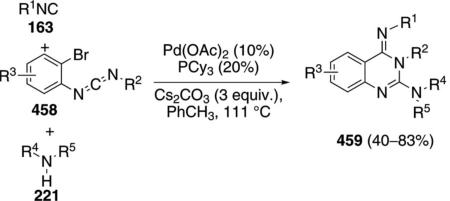

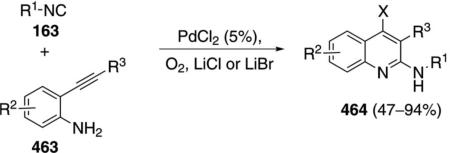

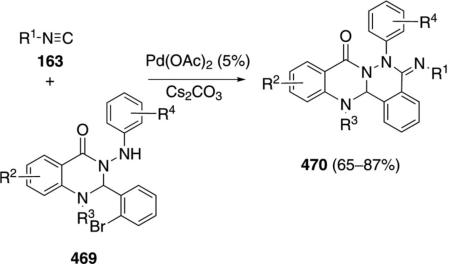

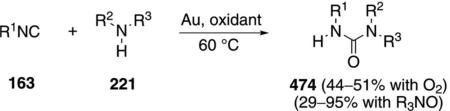

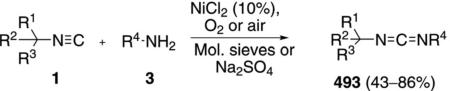

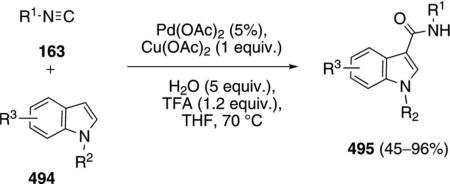

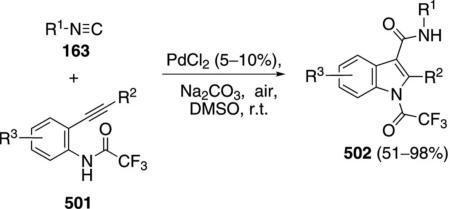

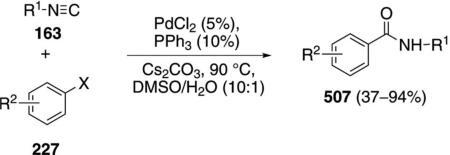

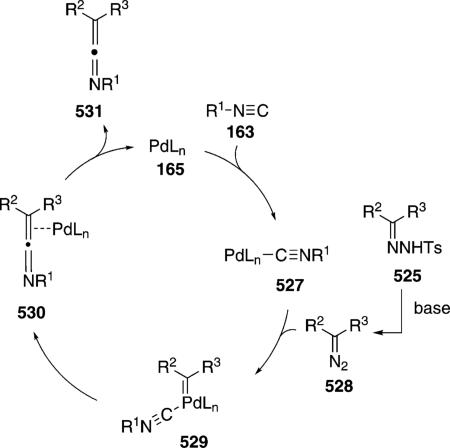

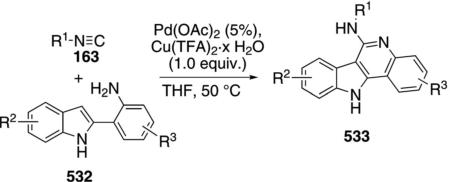

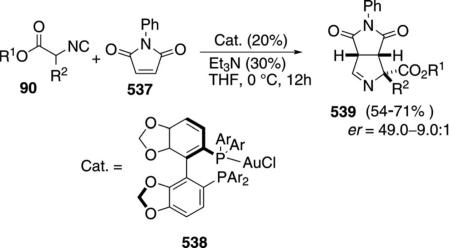

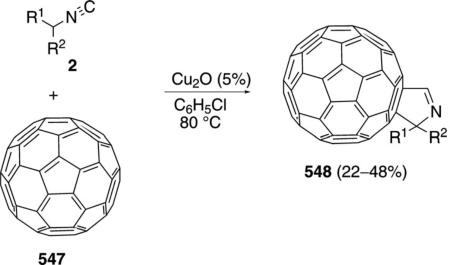

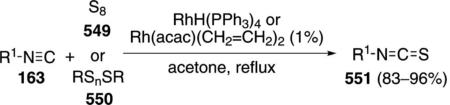

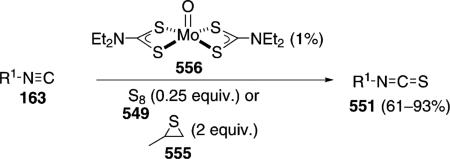

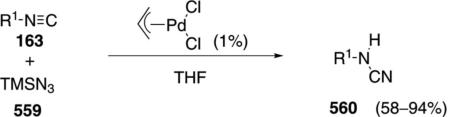

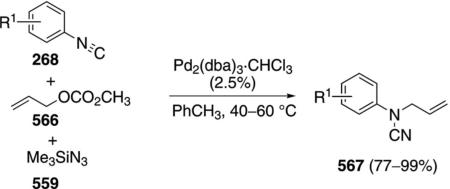

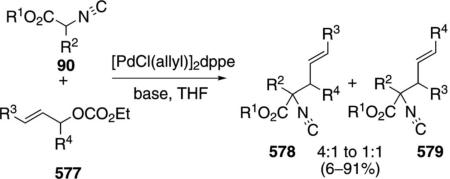

although it may involve successive isonitrile insertion into a π-allyl palladium complex.