Abstract

Objective

To understand collaborative care psychiatric consultants’ views and practices on making the diagnosis of and recommending treatment for bipolar disorder in primary care using collaborative care.

Method

We conducted a focus group at the University of Washington in December 2013 with nine psychiatric consultants working in primary care-based collaborative care in Washington State. A grounded theory approach with open coding and the constant comparative method revealed categories where emergent themes were saturated and validated through member checking, and a conceptual model was developed.

Results

Three major themes emerged from the data including the importance of working as a collaborative care team, the strengths of collaborative care for treating bipolar disorder, and the need for psychiatric consultants to adapt specialty psychiatric clinical skills to the primary care setting. Other discussion topics included gathering clinical data from multiple sources over time, balancing risks and benefits of treating patients indirectly, tracking patient care outcomes with a registry, and effective care.

Conclusion

Experienced psychiatric consultants working in collaborative care teams provided their perceptions regarding treating patients with bipolar illness including identifying ways to adapt specialty psychiatric skills, developing techniques for providing team-based care, and perceiving the care delivered through collaborative care as high quality.

Keywords: Collaborative care, bipolar disorder, primary care

1. Introduction

It is well established that the majority of mental health care delivered in the United States is provided in general medical settings such as primary care (1). However, there are major gaps in the quality of mental health care provided in primary care (2,3). Health service models have been developed to enhance accurate diagnosis and quality of mental health care for patients with psychiatric illnesses seen in primary care, with collaborative care having the most extensive body of research supporting its effectiveness (4–8). Many large health systems have implemented collaborative care into primary care settings with the aim to improve quality of care and outcomes for patients with psychiatric illness.

Collaborative care is a population-based treatment involving enhanced case identification, patient education to improve self-management, proactive patient follow-up, a patient registry, a clinical care manager, and a consulting psychiatrist. In collaborative care, the consulting psychiatrist regularly and systematically reviews a caseload of patients maintained in a registry with the clinical care manger, makes diagnostic and treatment recommendations, and may evaluate patients in person or by telemedicine when needed, such as when non-response to standard treatments occurs (5). Collaborative care for depression and anxiety in primary care is cost-effective (9) and is associated with improved mental and general health outcomes (4, 10), improved quality of life (4), and increased patient and clinician satisfaction (10).

Most collaborative care clinical trials focused on the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders in primary care (4, 7). However, dissemination of collaborative care into large health systems has revealed that clinicians working in collaborative care often face diagnosing and treating other more severe and complex psychiatric illnesses including bipolar disorder (11). Despite research showing that bipolar spectrum illnesses may occur in up to 10% of primary care patients in some primary care settings (12), and that the prevalence of bipolar disorder in primary care is approximately twice the prevalence in the general population (12–14), few studies are available to guide collaborative care consultation by psychiatrists in helping to improve the diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder in primary care. Moreover, despite the high prevalence, primary care clinicians are generally less comfortable with diagnosing and treating bipolar disorder compared to major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders, and view patients with bipolar disorder as complex (15).

The aim of this pilot study is to gain a preliminary understanding of consulting psychiatrists’ views and current practices on diagnosis and management of patients with bipolar disorder in primary care settings using a collaborative care model. Understanding consulting psychiatrists’ views may inform implementation of tools and techniques that assist in accurate recognition of, and delivery of high quality treatment to, patients with bipolar disorder treated in collaborative care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study setting

We conducted a focus group at the University of Washington in December 2013 with nine psychiatric consultants (eight consulting psychiatrists and one consulting psychiatric nurse practitioner) from the Mental Health Integration Program (MHIP). MHIP is an integrated care program serving patients with medical, mental health and substance misuse needs in over 140 safety net clinics such as community health centers and federally qualified health centers in Washington State. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington determined that this study was exempt from full review. We followed the COREQ method of reporting qualitative research for this report (16).

Clinicians working in MHIP provide collaborative care based on the IMPACT model (5, 6), which includes approximately two hours a week doing systematic caseload review with care managers using a web-based disease registry system that tracks patient visit dates, clinical progress, treatment history, and other information. Standardized clinical measures such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (17), Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (18), Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) (19), and Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) (20) are integrated into the registry and available for care managers’ use with patients. Registry use and results of these measures help to facilitate systematic case reviews by consulting psychiatrists. Clinicians working in MHIP can also refer patients from primary care to community mental health clinics for up to six months of treatment.

2.2 Patient characteristics in MHIP

Detailed characteristics of 740 patients with bipolar disorder treated in MHIP are described in a separate report (21), but summarized here. The sample was 44% female, with over half (57%) having received prior outpatient psychiatric care and one-third with one or more inpatient psychiatric hospitalization (21). Approximately half of patients reported concerns about their housing situation, one-third lacked dependable transportation, and 15% were homeless (21). Additionally, patients with bipolar disorder in MHIP demonstrated a high psychiatric symptom burden measured by standardized tools such as the PHQ-9 (17,21).

2.3 Personal characteristics of the research team and relationship with participants

The authors included three psychiatrists working in primary care settings, one family medicine physician, and one health services researcher with expertise in qualitative research methods. The focus group interviewer (JMC) had known most of the other consulting psychiatrists in MHIP for approximately one year due to working together in MHIP. Focus group participants understood that the leader had a research interest in treatment of bipolar disorder in primary care.

2.4 Focus Group Questions

Prior to holding the focus group interview, the authors developed seven guide questions used by the interviewer to prompt discussion among participants. Questions were developed through literature review, author discussion, and consultation with experts in collaborative care. The participants were unaware of the questions prior to the meeting. The interview guide consisted of the following seven questions: 1) How comfortable are you with diagnosing bipolar disorder in collaborative care?, 2) What clinical information do you seek when a care manager tells you that a patient has bipolar disorder?, 3) How do you manage the diagnostic uncertainty?, 4) What has been your experience recommending initiating treatment of bipolar disorder in collaborative care?, 5) What has been your experience monitoring treatment of bipolar disorder in collaborative care?, 6) What factors make you decide to see the patient?, 7) What has been your experience transferring patients to a higher level of care?

2.5 Participant selection and characteristics

Twenty three psychiatric consultants were working in MHIP at the time of this study; all were invited to participate in the focus group meeting. MHIP consulting psychiatrists were notified of the focus group meeting in person one month before the date of the focus group, and email reminders were subsequently sent. Participation in the focus group session was voluntary and no participants dropped out. Nine clinicians (8 psychiatrists and 1 psychiatric nurse practitioner) participated in the focus group. Four of the participants were women. The median age was 41 years (interquartile range [IR] 36, 57 years). Participants had been in clinical practice for a median of 6 years (IR 2, 14 years). Participants had been in practice in the MHIP collaborative care model for a median of 4 years (IR 2, 5 years).

2.6 Focus group procedure

The focus group session was audio-recorded and the conversation was transcribed verbatim. Field notes were taken during the session to enhance the transcription. All participants were encouraged to discuss their experiences. Guidelines were introduced by the interviewer to ensure that general, rather than specific, information about patients would be shared. In addition to the 9 participants and 1 group leader, one project manager was present at the focus group session to help organize and record the meeting.

2.7 Data analysis

The transcription was analyzed using a grounded theory approach (22). Using open coding and the constant comparative method (22, 23), we employed the Atlas.Ti Version 7.1 program to help sort and organize the data into major categories. Axial coding then followed, where through interactive discussion among authors, relationships between and within categories were found. Major categories were identified and three themes emerged from within categories. Saturation was reached when no new themes emerged. Reliability and validity of the three major themes were determined when consensus was reached from review and re-review by the focus group participants. Reliability was also enhanced by purposively including study participants with expertise in collaborative care

3. Results

We identified three emergent major themes contributing to the consulting psychiatrists’ experiences caring for patients with bipolar disorder in collaborative care: 1) the importance of working as a collaborative care team, 2) the strengths of collaborative care for treating bipolar disorder, and 3) adapting psychiatric specialty clinical skills to primary care.

3.1 Theme 1: Importance of working as a team

Most participants emphasized that providing high quality care to individuals with bipolar disorder required working closely with all members of the collaborative care team including the care manager, primary care clinician, and the patient. The care manager was described as the central team member. Many consulting psychiatrists described providing care managers with education on bipolar disorder on a weekly basis; for example by describing bipolar disorder phenomenology, and encouraging them to ask patients questions directly related to bipolar disorder.

“So I spend a lot of time on educating [care managers] on how to take a mood history, to look for periods of shifts in mood.”

“And so I get [care managers] to really ask, ‘What happened and what did other people notice about you when you were in this mood?’”

“I’ve seen care managers become incredibly adept at doing a really good mood history.”

Others identified care coordination among the collaborative care team as a key job of the care manager, such as ensuring that lab studies such as lithium levels recommended by the psychiatrist are ordered in primary care clinic and patients get their blood drawn or other samples collected before leaving the clinic.

“They’re effective in walking the patients to the lab, or…making sure that those things happen at the end of their visit.”

Participants also stressed the need for collaborative care teams to work together to develop a standard technique for assessing bipolar disorder, which many participants described as using a combination of structured instruments such as the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (17), follow-up clinical questions, and collateral information.

“I usually start by looking at the way the patient has filled out the screening questionnaire, either the MDQ or the CIDI, and see if the care manager has [asked] follow-up questions which address the duration of symptoms, whether symptoms occur simultaneously, and so on.”

“When I’m deeply suspicious of any bipolar diagnosis…I insist that the care coordinator talk with somebody who knows the patient well.”

The patient’s role in collaborative care was also emphasized. One consulting psychiatrist described how patients and care managers work together to determine which patients should be seen directly by the collaborative care psychiatrist:

“[Who I see for an in-person consultation] is getting identified between the patient and the care manager.”

Part of the discussion revealed that effective teamwork over time can increase care manager, primary care clinician and psychiatric consultant comfort with managing bipolar disorder in primary care. One experienced consulting psychiatrist described recently receiving questions from several primary care clinicians regarding bipolar disorder treatment, which differed from her early experience in collaborative care in which she met resistance to treating bipolar disorder. The consulting psychiatrist attributed this shift to having successfully worked as a team in collaborative care at that clinic for over four years, and had spent time addressing primary care clinicians’ questions about bipolar disorder.

“When I first started and the clinics were newer to collaborative care there was less comfort…in prescribing and monitoring mood stabilizers and antipsychotics. [Now] I do find that primary care physicians generally don’t have any problems…taking a recommendation on antipsychotics.”

3.2 Theme 2: Strengths of collaborative care for treating bipolar disorder

Consulting psychiatrists acknowledged the general benefits of using collaborative care to deliver specialty psychiatric care to a primary care population. However, they also emphasized collaborative care’s strengths in managing bipolar disorder in a safety net population where the prevalence of bipolar disorder is higher than in other primary care settings (12).

A major strength participants described was being able to utilize repeated observations of patients treated in collaborative care, which participants felt enhanced diagnostic accuracy and quality of bipolar disorder treatment. These observations included prospective follow-up clinic visits with the care manager or primary care clinician, review of prior treatment records, and observations from patients’ family members. The patient registry also facilitated patient tracking and outreach efforts, and provided clinicians with information used to make treatment adjustments.

“We often get more frequent assessments, because we have the data from the primary care provider’s visits, and the care manager’s visits, and the care managers see people more frequently than I typically would in my outpatient visits.”

“Sometimes I actually think there are pluses to seeing a patient in collaborative care in terms of getting that longitudinal assessment that’s really needed to make a good mood disorder diagnosis.”

“The care managers are going to get people back in [to the clinic].”

Similar to other clinical settings such as emergency rooms, many consulting psychiatrists described sometimes wanting additional clinical information before making a firm diagnosis or recommending treatment for a patient. However, as exemplified by the following quotes, the participants emphasized that collaborative care offers the opportunity to have several clinicians closely follow patients and often permitted psychiatric consultants to make provisional diagnoses and treatment recommendations.

“I document it as a provisional diagnosis with clear guidelines to the team about how we’re going to monitor and follow this patient closely”

“I actually feel like in some ways my ability to titrate medications in collaborative care is more effective than in my outpatient practice where I’m trying to facilitate all [components of care]…so that surprised me. I wasn’t expecting that to be true in collaborative care. But you have a kind of army of people helping you [care for the patients].”

“We can actually make more rapid adjustments to medications in the primary care setting than if we refer them [to a psychiatry clinic]”.

Furthermore, one psychiatric consultant stressed that in the safety net primary care clinic she consults with, patients have few options other than collaborative care for outpatient psychiatric treatment. This fact has led her to recommend initiating bipolar disorder treatment despite lacking comprehensive clinical information in some cases, as suggested by the following perspective.

“I personally balance the risks of the harm of doing something versus the harm of not doing something…sometimes I treat even in the lack of perfect information, as long as I’m comfortable that there’s going to be follow-up… but whether the treatment is for major depression or bipolar depression really depends on the best information I have at that moment...I am often faced with choosing to treat in the face of imperfect information”

3.3 Theme 3: Adapting specialty psychiatric skills to primary care

Participants acknowledged that bipolar disorder is generally viewed as a “specialty illness”, and that most collaborative care teams expected consulting psychiatrists to have detailed knowledge of the natural history and symptoms of bipolar disorder, as well as treatment options for patients with co-occurring bipolar disorder, substance use, and chronic illnesses such as diabetes. However, participants also discussed challenges associated with adapting specialty clinical skills to collaborative care, such as diagnosing hypomania without directly observing a patient to conduct a mental status examination. Some participants suggested that instruction from colleagues on the clinical practice of collaborative care helped with adapting specialty skills to collaborative care.

Several participants reported needing to learn techniques for assessing bipolar disorder psychopathology while indirectly caring for patients, and explained relying on the care manager to assess patients’ experiences with symptoms.

“Mania is not just an internal mood state. It has some outward manifestations in terms of speech or movement or decisions or behavior…and sometimes patients feel anxious or agitated but it is not really mania. And so I get care managers to really ask [about symptoms].”

“There are important distinctions…in differentiating those states…So I imagine that the consulting psychiatrist giving, feeding some questions to the care manager, is actually quite important in helping.”

Additionally, many psychiatric consultants agreed that the style of assessments and recommendations made in collaborative care differed from those made in psychiatry clinics. Furthermore, understanding “how primary care worked” (i.e. the barriers primary care clinicians face, and competing clinical demands in primary care) allowed psychiatric consultants to provide assessments and treatment recommendations that were more consistent with the daily practice of primary care clinicians.

“You can’t just say “titrate divalproex”, you actually really need to give explicit directions around how to do that. And in the end they’re more interested in that than in all of the kind of decision-making about why you think that the person has bipolar disorder.”

In MHIP, the collaborative care team can refer patients for up to six months of treatment in community mental health clinics. Psychiatric consultants expressed developing a deeper understanding of the challenges associated with referring a patient with bipolar disorder from primary care to a community mental health clinic, due to experiencing some of the same barriers faced by primary care clinicians during referral.

“Yeah, I would say the most common thing is that until somebody gets sick enough, it’s actually pretty hard to [refer the patient to specialty mental health].”

“Yeah, I was thinking of two cases that…made their way [from primary care] to specialty care by way of the inpatient psychiatry unit.”

“I think it’s sometimes the sickest patients [that have] the hardest time…You can make all the referrals but the patient will have a hard time actually presenting himself to the [specialty mental health clinic].”

However, consultants described that in many circumstances, the collaborative care treatment team and patient prefer continuing with care delivered in primary care instead of transferring care to a community mental health clinic.

“It’s been my experience with one or two patients in trying to get them to [specialty mental health] that they have developed such a relationship with their care manager too that they’re reluctant to go get treatment elsewhere, even if it could be more direct treatment.”

“[I] worry that their treatment may not be as systematic or quite as good in referring them out, even though it could be more direct or has the potential to be more direct, [the patient] could also have a long wait in order to get treatment.”

“I would say the other piece is that…I often end up helping the primary care provider manage the patient’s meds, because it’s really hard to see a prescriber in many community health centers locally.”

3.4 Conceptual Model

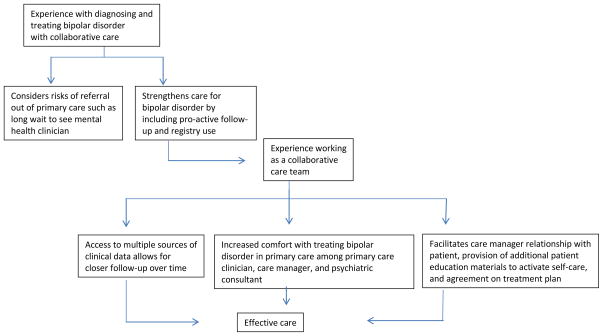

Given our grounded theory approach (22, 23), these three main themes derived from our analysis of the data led to development of a non-temporal conceptual model illustrating psychiatric consultants’ experiences with caring for patients with bipolar disorder in collaborative care (Figure 1), reflecting a theoretical pattern of how collaborative care psychiatrists view the treatment of bipolar disorder in primary care. Psychiatric consultants tended to favor the strengths of collaborative care including use of care manager and patient registry over the potential risk of the patient dropping out of care during referral to a mental health clinic. The experience clinicians gained working together to treat patients with bipolar disorder in collaborative care led to close patient follow-up and provision of effective care.

Figure 1.

Non-temporal Conceptual model of collaborative care psychiatrists’ views on treating bipolar disorder in primary care

4. Discussion

Our focus group discussion on the recognition and treatment of bipolar disorder, involving nine psychiatric consultants working in collaborative care, revealed three major themes. These themes included the importance of working as a collaborative care team, the strengths of collaborative care for treating bipolar disorder, and the need to adapt specialty psychiatric clinical skills to the primary care setting. This study adds to the growing literature on the experiences of clinicians working in collaborative care, and its impact on the recognition and treatment of bipolar disorder in primary care.

Psychiatric consultants in this study discussed valuing team effort, including the patients’ efforts, when caring for individuals with bipolar disorder in collaborative care. This finding is consistent with prior research (24) showing that collaborative care clinical care managers treating low income mothers with depression valued teamwork, including frequent consultation with the psychiatric consultant, team sessions with the patient involving the care manager and consulting psychiatrist, and efforts to enhance patient participation in treatment through use of an engagement session (25).

Enhancing patient participation and increasing patient self-efficacy are two key components of implementing effective treatment for primary care patients with complex illnesses such as bipolar disorder (26). Patients with mood instability have previously reported a strong preference for patient-centered care, in terms of having a more reciprocal and trusting relationship with clinicians, feeling listened to, receiving explanations for why symptoms occur, and enhancing their self-care (27). Additionally, psychiatric consultants in our study reported that patients with bipolar disorder often preferred receiving treatment in primary care rather than specialty mental health, and that many patients developed relationships with the care manager and treatment team that were seen as beneficial by both patients and the psychiatric consultants. Our findings suggest that collaborative care offers treatment consistent with patient’s preferences.

Psychiatric consultants experienced challenges associated with referring moderately-ill patients with bipolar disorder from primary care settings to community mental health centers including long waiting times for an appointment with a mental health clinician and concerns that patients would “fall through the cracks” due to lack of use of a patient registry in the mental health center. Collaborative care includes the use of a highly trained, pro-active care manager and a patient registry which, together, often lead to increased patient participation in their treatment (5). Furthermore, collaborative care provided clinicians with access to a patient registry, which assisted with tracking and treating their population of patients with bipolar disorder.

Primary care clinicians also address a wide spectrum of concurrent general and mental health problems such as mood disorders, tobacco use, and diabetes. Approximately one-half of individuals with bipolar disorder smoke (28), one-half have significant medical comorbidity (29), and approximately one-fifth of older patients with bipolar disorder have diabetes (30). Furthermore, more severe bipolar disorder symptoms predicted use of general medical services, but not mental health counseling, among patients with bipolar disorder enrolled in one comparative effectiveness trial (31). Another study found that from 1995 to 2010, the percentage of clinic visits resulting in either a bipolar disorder diagnosis or prescription of an antipsychotic medication (potential treatment for bipolar disorder) have grown more rapidly in primary care clinics compared to psychiatric clinics (32). These findings suggest that both the diagnosis of and potential treatment prescriptions for bipolar disorder are increasing in primary care settings. Prior research on population-based care for individuals with bipolar disorder treated in mental health care settings has shown significant reductions in manic symptom burden and a greater decline in depression symptoms compared to usual care, suggesting that collaborative care for patients with bipolar disorder treated in primary care is also effective (33).

Limitations include involvement only of psychiatric consultants working in safety net primary care settings in Washington State and those consultants attending the focus group meeting, and potential biases related to development of our focus group questions which was done by the authors. Patients with bipolar disorder may present more frequently to safety-net rather than non-safety-net settings; thus our findings may not be generalizable to psychiatrists working in collaborative care models outside of safety-net clinics. The MHIP clinical program in which the psychiatric consultants from this study work has been in-place since 2008 which may limit the application of our findings to newer collaborative care programs.

5. Conclusions

Experienced psychiatric consultants working in collaborative care teams identified ways to adapt specialty mental health care skills to primary care settings and developed techniques for providing team-based care by providing education to care managers, primary care clinicians, and patients about bipolar disorder, and by tracking patients using a registry so that treatments could be adjusted based on multiple clinical observations. Additionally, psychiatric consultants perceived that care delivered to individuals with bipolar disorder through the collaborative care model was of high quality.

Acknowledgments

Grant funding: 5-T32MH020021-15

The authors wish to thank Marc Avery, MD for allowing meeting time to hold the focus group, Cassandra Vaughn, MS for her assistance with facilitating multiple aspects of this project, and Tess Grover, BA for recording and transcribing the meeting.

Footnotes

Prior presentations: None

Disclosures: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, Laje G, Correll CU. National trends in the mental health care of children, adolescents, and adults by office-based physicians. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:81–90. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein MB, Sherbourne CD, Craske MG, et al. Quality of care for primary care patients with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2230–2237. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seelig MD, Katon W. Gaps in depression care: why primary care physicians should hone their depression screening, diagnosis and management skills. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:451–458. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318169cce4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ, et al. Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katon WJ, Unützer J. Health reform and the Affordable Care Act: the importance of mental health treatment to achieving the triple aim. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74:533–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mental Health Integration Program (MHIP) [Accessed May 2nd, 2014]; http://integratedcare-nw.org/

- 7.Korsen N, Pietruszewski P. Translating evidence to practice: two stories from the field. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009;16:47–57. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huffman JC, Niazi SK, Rundell JR, Sharpe M, Katon WJ. Essential articles on collaborative care for treatment of psychiatric disorders in medical settings: a publication by the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine Research and Evidence-Based Practice Committee. Psychosomatics. 2014;55:109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacob V, Chattopadhyay SK, Sipe TA, et al. Economics of collaborative care for management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katon WJ, Lin EHB, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vannoy SD, Mauer B, Kern J, et al. A learning collaborative of CMHCs and CHCs to support integration of behavioral health and general medical care. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:753–758. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.7.pss6207_0753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cerimele JM, Chwastiak LA, Dodson S, Katon WJ. The prevalence of bipolar disorder in general primary care samples: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cerimele JM, Chwastiak LA, Dodson S, Katon WJ. The prevalence of bipolar disorder in primary care patients with depression or other psychiatric complaints: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2013;54:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant RW, Ashburner JM, Hong CS, Chang Y, Barry MJ, Atlas SJ. Defining patient complexity from the primary care physician’s perspective: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:797–804. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-12-201112200-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Calabrese JR, Farley PA, et al. Composite international diagnostic interview screening scales for DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:1625–1637. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirschfeld RMA, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL, et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the mood disorder questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1873–1875. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerimele JM, Chan YF, Chwastiak LA, Avery M, Katon W, Unutzer J. Bipolar disorder in primary care: clinical characteristics of 740 primary care patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2014 Apr 15; doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300374. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cresswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook DA, Sorensen KJ, Wilkinson JM, Berger RA. Barriers and decisions when answering clinical questions at the point of care: a grounded theory study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1962–1969. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang H, Bauer AM, Wasse JN, et al. Care managers’ experiences in a collaborative care program for high risk mothers with depression. Psychosomatics. 2012;54:272–276. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grote NK, Swartz HA, Geibel SL, et al. A randomized controlled trial of culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:313–321. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azrin ST. High-impact mental health-primary care research for patients with multiple comorbidities. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:406–409. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bilderbeck AC, Saunders KEA, Price J, Goodwin GM. Psychiatric assessment of mood instability: qualitative study of patient experience. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:234–239. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.128348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chwastiak LA, Rosenheck RA, Kazis LE. Association of psychiatric illness and obesity, physical inactivity, and smoking among a national sample of veterans. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kemp DE, Sylvia LG, Calabrese JR, et al. General medical burden in bipolar disorder: findings from the LiTMUS comparative effectiveness trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;129:24–34. doi: 10.1111/acps.12101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kilbourne AM, Cornelius JR, Han X, et al. Burden of general medical conditions among individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2004;6:368–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sylvia LG, Iosifescu D, Friedman ES, et al. Use of treatment services in a comparative effectiveness study of bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:1119–1126. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olfson M, Kroenke K, Wang S, Blanco C. Trends in office-based mental health care provided by psychiatrists and primary care physicians. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:247–253. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Unutzer J, Bauer MS, Operskalski B, Rutter C. Randomized trial of a population-based care program for people with bipolar disorder. Psychol Med. 2005;35:13–24. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]