Abstract

Cholesterol is essential for neuronal physiology, both during development and in the adult life: as a major component of cell membranes and precursor of steroid hormones, it contributes to the regulation of ion permeability, cell shape, cell–cell interaction, and transmembrane signaling. Consistently, hereditary diseases with mutations in cholesterol-related genes result in impaired brain function during early life. In addition, defects in brain cholesterol metabolism may contribute to neurological syndromes, such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), Huntington's disease (HD), and Parkinson's disease (PD), and even to the cognitive deficits typical of the old age. In these cases, brain cholesterol defects may be secondary to disease-causing elements and contribute to the functional deficits by altering synaptic functions. In the first part of this review, we will describe hereditary and non-hereditary causes of cholesterol dyshomeostasis and the relationship to brain diseases. In the second part, we will focus on the mechanisms by which perturbation of cholesterol metabolism can affect synaptic function.

Keywords: brain disease, cholesterol metabolism, cognition

See the Glossary for abbreviations used in this article.

Introduction

Cholesterol is an essential constituent of eukaryotic membranes, and as such, it impacts on nearly all aspects of cellular structure and function [1–5]. In addition, cholesterol serves as precursor for steroid hormone and bile acid synthesis [6] and therefore has a critical role in body metabolism (Fig 1). Furthermore, cholesterol can also influence cell function through its biologically active oxidized forms: oxysterols [7–11].

Figure 1. Cellular cholesterol homeostasis.

Diagram summarizing how cells ensure cholesterol homeostasis. Cells synthesize cholesterol from acetyl-CoA by a long series of enzymatic steps requiring energy and molecular oxygen. Intermediates of the pathway serve as precursors for other biologically active molecules. Highlighted enzymes are 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR), which is rate-limiting for the mevalonate pathway and inhibited by statins, 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR24) and 7-dehydrocholesteol reductase (DHCR7), whose defects cause rare human diseases. Cells can take up cholesterol by receptor-mediated endocytosis of lipoproteins bearing apolipoproteins. In this pathway, Niemann-Pick Type C Protein 1 and NPC2 mediate cooperatively the exit of cholesterol out of the endosomal-lysosomal system and thereby allow for its incorporation into the intracellular pool. Defects in either protein cause the lysosomal storage disorder Niemann-Pick Type C. Overload by cholesterol is prevented by its intracellular esterification and subsequent storage in lipid droplets and by its release. Cholesterol is released either as a complex with apolipoprotein-containing lipoproteins via members of the ATP-binding cassette transporters or after conversion to oxysterols. Examplary proteins for each process are indicated. The relative contribution of each pathway to cholesterol homeostasis is probably cell type-specific. The post-lanosterol steps of cholesterol biosynthesis are divided into Bloch and Kandutsch–Russell pathways, which share enzymatic stages but produce C24 double-bond reduced cholesterol at different steps.

Cellular cholesterol synthesis is a complex and resource-intense process: it starts with the conversion of acetyl-CoA to 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA by HMG-CoA synthase, which is then converted to mevalonate by HMG-CoA reductase. The latter constitutes the only known rate-limiting and irreversible step in cholesterol synthesis. This is followed by a long series of enzymatic reactions that convert mevalonate into 3-isopenenyl pyrophosphate, farnesyl pyrophosphate, squalene, lanosterol and, through a 19-step process, to cholesterol (Fig 1) [12]. Whether other enzymatic steps in the pathway, posterior to squalene synthesis, are rate-limiting is unknown. Cholesterol is synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum from where it is distributed to cellular membrane compartments by vesicular and non-vesicular transport mechanisms (Fig 1) [13]. Cells can also import sterols through receptor-mediated endocytosis of lipoproteins and the subsequent export of unesterified cholesterol from lysosomes (Fig 1) [14,15]. It is well established that cells regulate their cholesterol content by an exquisite feedback mechanism that balances biosynthesis and import. Cells sense their level of cholesterol by membrane-bound transcription factors known as sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs), which regulate the transcription of genes encoding enzymes of cholesterol and fatty acid biosynthesis as well as lipoprotein receptors [16].

Cholesterol is not uniformly distributed within membranes and across different cellular compartments. A recent study in vitro suggests that cholesterol is enriched in the cytosolic (inner) leaflet of the plasma membrane [17]. Moreover, there is evidence that the plasma membrane contains nano/micro-domains that are enriched in cholesterol, the so-called ‘lipid rafts’. These rafts are thought to represent highly dynamic structures dispersed throughout the membrane of cells that recruit downstream signaling molecules upon activation by external or internal signals [18]. Rafts also contain a high amount of sphingomyelin, which is enriched in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, indicating that some trans-bilayer translocation must occur to form and stabilize these domains [19]. In neurons, membrane rafts have been detected at synapses, where they are thought to contribute to pre- and postsynaptic function [20–24].

The brain contains 23% of all cholesterol in the body [25], and within the brain, a large fraction of cholesterol is present in the myelin sheath that is formed by oligodendrocytes to insulate axons (Fig 2). Neurons and astrocytes probably also contain large amounts of cholesterol to maintain their complex morphology and synaptic transmission. All cells in the brain are cut off from cholesterol supply by the blood, because the blood–brain barrier prevents entry of cholesterol-rich lipoproteins. Therefore, all cholesterol in the CNS is made locally [26,27]. The fact that brain cholesterol metabolism is separated from the rest of the body warrants caution when causal correlations between high blood cholesterol and brain pathologies are suggested: in the presence of an intact blood–brain barrier neurons and all other cells in the brain are not influenced by circulating cholesterol (Fig 2). On the other hand, there is a constant efflux of cholesterol from the brain, which is enabled by the neuron-specific cytochrome P450 oxidase Cyp46a1. This enzyme hydroxylates cholesterol to 24S-hydroxycholesterol (24-OHC), which crosses the blood–brain barrier, enters the circulation and is metabolized by the liver (Fig 2) [28].

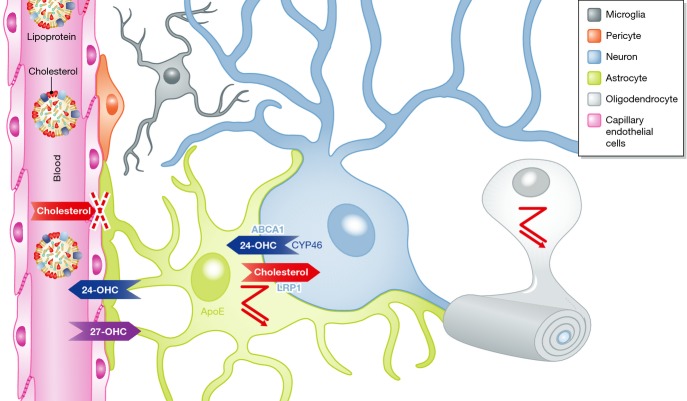

Figure 2. Brain-specific aspects of cholesterol metabolism.

Brain cells are cut off from blood supply as the blood–brain barrier prevents entry of lipoproteins. Cholesterol is synthesized by different types of glial cells as indicated by the zagged pathway symbol. Some neurons may import cholesterol from APOE-expressing astrocytes via lipoprotein uptake (LRP1) and hydroxylate surplus cholesterol to 24-OHC, which is excreted via ABCA1 and which enters the blood circulation. 24-OHC is able to cross the blood–brain barrier where it may signal the level of plasma cholesterol levels to cells in the brain. Cholesterol-related proteins with cell-specific distribution are indicated.

In the mouse brain, cholesterol synthesis is high until the second post-natal week and then decreases significantly and remains low in the adult [29]. Age-associated cholesterol reduction was also observed in postmortem human samples [30]. Importantly, the rate of cholesterol synthesis in individual brain cells is unknown. Whereas oligodendrocytes probably rely on their own cholesterol synthesis to form and maintain myelin, neurons may import cholesterol from astrocytes. The high metabolic rate of neurons probably enforces a constant turnover of cholesterol throughout life (Fig 2) [31].

Enzymatic deficiencies in the cholesterol synthesis pathway are responsible for a number of inherited disorders with severe neurodevelopmental defects. In addition, alterations in brain cholesterol are thought to be critically involved in a number of neurodegenerative pathologies, in some cases as the suspected cause and in others as a consequence. In the following sections, we will summarize our current knowledge of how defects in cholesterol metabolism and transport can lead to, or be part of, brain dysfunction.

Cholesterol in brain disease: hereditary causes

The important role of cholesterol for CNS function is exemplified by a number of rare hereditary diseases caused by mutations in cholesterol-related genes. The reader interested in a comprehensive description of these diseases should refer to excellent reviews [32–34]. Here, we will focus on three diseases that are linked to mutations in cholesterol metabolism and transport steps: the Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome, desmosterolosis and the Niemann-Pick type C disease. In addition, we will briefly comment on the recent discovery of an association between cholesterol metabolism and Rett syndrome.

Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome (SLOS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the gene encoding the enzyme 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7, Fig 1). This enzyme catalyzes the last step in the Kandutsch–Russell pathway of cholesterol biosynthesis. There are reports of 154 different mutations in DHCR7 in SLOS patients [35]. In the most severe cases, the mutation causes fetal or newborn death, due to severe malformations and multiple organ failure. The milder cases can present multi organ defects of different severity: facial and cranial malformations, hypospadia or complete gonadal absence and even gender reversal, gastrointestinal symptoms, limb malformations, liver disease and cardiac defects (for comprehensive descriptions see [36–38]). SLOS patients present, with different degree of gravity, intellectual disabilities, delayed motor and language maturation, affective disorders and sleeping problems. The signs and symptoms may be due to reduced brain cholesterol levels. Severely affected SLOS patients have plasma cholesterol concentrations at 2% of the normal level and low cholesterol content in all tissues, especially in the brain [39]. Patients with milder symptoms can show normal plasma concentrations of cholesterol, probably due to residual synthesis capacity and dietary import. However, even in these mild cases, circulating cholesterol cannot compensate for the brain deficits due to the blood–brain barrier, suggesting that low cholesterol levels in the brain are the primary cause of the neurological symptoms in SLOS patients. Alternatively, these symptoms may be due to accumulation of 7,8-dehydrodesmosterol, which is the substrate of DHCR7, or its oxidized metabolites [36]. Notably, some of the teratogenic effects by impaired cholesterol synthesis are probably due to defects in sonic hedgehog signaling [40,41]. During autoprocessing of sonic hedgehog, a cholesterol molecule is covalently added to the amino terminus and regulates protein function [42,43].

Desmosterolosis is a rare, autosomal recessive disease caused by mutations in the dhcr24 gene (Fig 1). The enzyme encoded by this gene catalyzes the reduction of desmosterol to cholesterol, the last step in the Bloch pathway of cholesterol synthesis [44]. dhcr24 was first identified as a gene involved in human steroid synthesis due to its similarity to DIMINUTO/DWARF1 (dwf1). The product of this gene catalyzes a similar step in sterol synthesis in plants, which is essential for normal growth and development in Arabidopsis [45,46]. In addition to its enzymatic activity, DHCR24 contains a binding site for p53 and Mdm2, which mediate oncogenic and oxidative stress signaling [47]. Patients with DHCR24 mutations present severe brain defects including microcephalia, hydrocephalia, ventricular enlargement, defects in the corpus callosum, and thinning of white matter and seizures. Disease signs may be attributed to reduced cholesterol levels or to accumulation of desmosterol. In addition, reduced levels of DHCR24 in the adult brain may enhance sensitivity to oxidative stress [48,49].

Niemann-Pick C disease is an autosomal recessive disorder caused in 95% of the cases by mutations in the npc1 or npc2 genes, which cause progressive visceral, neurological, and psychiatric symptoms and premature death. Neurologic symptoms and the age of onset vary strongly among patients. The symptoms include delayed development of motor skills, supranuclear palsy, gait problems, frequent falls, clumsiness, difficulties to speak and learn, and ataxia. The adult form presents psychiatric problems, cerebellar ataxia, and progressive dementia. Cataplexy, seizures, and dystonia are other common features [50,51]. At the histological level, NPC-deficient brains present neurons with enlarged neurites, ectopic dendrites, neurofibrillary tangles, neuroinflammation, and axonal dystrophy. In the advanced disease, neuronal death is the prominent feature, affecting specific cell types, particularly cerebellar Purkinje cells [52]. At the cellular level, NPC1 and NPC2 cooperate to mediate the exit of cholesterol from the endosomal-lysosomal system (Fig 1) [53–55]. Defects in either protein cause accumulation of unesterified cholesterol and gangliosides in late endosomes and lysosomes [56–58] with reduced cholesterol levels in the plasma membrane of NPC patient cells [59] and in axons of cultured neurons [60]. Moreover, endosomal organelle transport [61] and synaptic vesicle composition and morphology are affected [62]. Hence, the neurological and psychiatric symptoms in NPC disease may result, like in the previously mentioned diseases, from a combination of abnormal lipid accumulation and reduced cholesterol levels in specific membrane compartments [63].

Rett syndrome is an X-linked neurological disorder characterized by defective motor control, cognitive abilities, and social interactions, namely appearance of speech difficulties, stereotypic hand movements, problematic walking, seizures, intellectual disabilities, and autistic behavior. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in the X-linked mecp2 gene, which encodes a methyl DNA-binding protein that regulates gene expression [64]. Until recently, Rett syndrome was not associated with a defect in cholesterol metabolism. However, a recent study has shown that a suppressing mutation in the sqle gene, encoding for the squalene epoxidase that mediates a dedicated step in cholesterol synthesis, was sufficient to restore function and longevity in Mecp-2 null mice [65]. These data suggest that Mecp-2 may be involved in the transcriptional control of cholesterol metabolism. In support of this hypothesis, the expression of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coA reductase, squalene epoxidase, and Cyp46A1 was altered in Mecp-2 null mice in an age-dependent manner. Measurements of de novo cholesterol synthesis confirmed that sterol synthesis decreases in adult brains of Mecp-2 mutant mice. Administration of fluvastain, an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor with intermediate capacity to cross the blood–brain barrier [66], to Mecp-2 null mice lowered serum cholesterol levels, improved motor, cognitive and social behaviors and increased life span. In summary, while Rett syndrome is clearly associated with changes in cholesterol metabolism, it remains to be demonstrated whether Mecp-2 phenotypes are caused by neuron-specific defects in cholesterol metabolism [67].

Taken together, these rare genetic diseases underline that the brain is highly sensitive to perturbations of cholesterol synthesis and transport and that these defects cannot be rescued by manipulations of peripheral cholesterol levels.

Brain cholesterol and Alzheimer's disease

Apart from hereditary diseases with a clear-cut link to cholesterol, there are neurodegenerative diseases for which a contribution of impaired cholesterol metabolism to the disease has been proposed. One of the most studied cases is Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Twenty years ago, it was shown that the apolipoprotein E allele ε4 enhances the risk of late-onset familial and sporadic AD [68] and increases amyloid beta deposition in the brain [69]. This APOE variant is also associated with cardiovascular disease, atherogenicity, and high LDL-cholesterol levels in blood [70–72], raising the possibility that peripheral cholesterol dyshomeostasis could contribute to late-onset AD. Consistently, early work showed that rabbits fed with a high cholesterol diet develop intracellular accumulations of beta amyloid in brain cells [73]. Later on, clinical retrospective studies in humans showed that hypercholesterolemia predisposes to cognitive deficits, including dementias of the Alzheimer's type [74], and that chronic treatment with cholesterol-lowering statins seemed to prevent the disease [75,76]. More recently, a multisite, medical center-based analysis of early patients with AD confirmed a correlation between high LDL-cholesterol, low HDL-cholesterol and high PIB index, which measures the levels of cerebral Aβ with carbon C11-labeled Pittsburgh Compound B [77]. Several lines of evidence suggest that the link between elevated blood cholesterol and AD is related to vascular and inflammatory alterations (and associated diseases) rather than through changes in brain cholesterol [78–88]. In fact, atherosclerosis affects the cerebral vasculature, leading to plasma protein leakage, accumulation of lipid-containing macrophages, and vessel fibrosis, which causes hypoperfusion, local inflammation and, eventually, breakdown of the blood–brain barrier [78–80]. Moreover, there is good evidence that metabolic conditions characterized by high circulating cholesterol levels predispose to AD through gradual and persistent vascular defects in the brain [81–86]. In agreement with the clinical evidence, chronic hypoperfusion of the brain in rats and AD mice increased BACE1 expression, the concentration of Aβ fibrils and caused cognitive impairment [87,88]. In addition to hypoperfusion and inflammation, high blood cholesterol may also cause vascular defects predisposing to AD via oxysterols. These metabolites contribute to the atherogenic process by inducing endothelial cell dysfunction, adhesion of circulating blood cells, foam cell formation, and apoptosis of vascular cells [89]. Furthermore, hypercholesterolemia may predispose to AD by comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clinical studies revealed that a high proportion of patients with AD present T2DM [90], which often associates with hypercholesterolemia [91]. In this constellation, AD signs may also result from defects in brain insulin signaling [92].

On the other hand, predisposition to AD in cases of familial hypercholesterolemia with the ε4 variant of APOE may result from isoform-specific effects on brain cells. This could involve alterations in the metabolism of beta peptide, effects on synaptic function, and disturbance of cholesterol metabolism in the CNS [93]. Animal studies have shown that APOE levels are reduced in the brain of mice expressing human Apoε4, suggesting a shorter life span of this isoform. Moreover, Apoε4 has different properties than other Apoε isoforms, which may impair the glia-to-neuron transport of cholesterol, reduce myelin, and diminish the capacity to degrade the toxic amyloid peptide [94–100]. Still, the consequences of the inheritance of the ε4 allele ought to be put together with the vascular defects due to hypercholesterolemia and with the direct toxic effects of ε4 on the cerebrovascular system [101]. Interestingly, a recent study on a cohort of NPC patients revealed a correlation between APOE alleles and disease severity, which confirms an impact of cholesterol dyshomeostasis on neurodegeneration.

Recent data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) suggest that mutations in the lipid metabolism-related proteins ApoJ/Clusterin (CLU) and ABCA7 are risk factors for AD [102]. ApoJ/Clusterin is involved in lipid transport but also has heat-shock-like chaperone activity and regulates apoptosis, immunoglobulin interaction and complement defense [103,104]. Individuals carrying particular polymorphisms present elevated levels of LDL-cholesterol and vascular defects [105]. Aging mice deficient in ApoJ/Clusterin develop progressive glomerulopathy characterized by deposition of immune complexes in the thin membranes surrounding the capillary loops [106]. Mutations or polymorphisms in the ABCA family member ABCA1 are associated with Tangier disease or, in the less severe cases, with familial HDL deficiency. Both conditions are characterized by reduced levels of circulating HDLs and the deposition of cholesterol esters in peripheral tissues [107]. Hence, like for the ε4 allele of APOE, polymorphisms in these two proteins may predispose to AD by peripheral, vascular defects with or without direct changes in brain cholesterol. Future research will need to address what the relative and specific contributions of the diverse defects to AD predisposition are.

A link between brain cholesterol and AD was also suggested by several in vitro studies on neuronal, pseudo-neuronal, and non-neuronal cells over-expressing proteins involved in familial AD. Acute reduction of cholesterol levels after treatment of these cells with synthesis inhibitors like statins or sterol-extracting drugs as methyl-β-cyclodextrin, reduced the production and toxicity of amyloid beta peptide, suggesting that elevated levels of brain cholesterol can be the cause of AD [108]. Although early work showed that brain cholesterol is high in the brains of patients with AD, as a consequence of excess Aβ [109], others showed reduced total brain cholesterol and brain cholesterol synthesis in Alzheimer's disease patients [110–117]. These studies reported a reduction in the lipid bilayer width of neurons, a 30% reduction in free, unesterified cholesterol in the temporal gyrus but not in the cerebellum [113] and a significant reduction of cholesterol levels in the whole-brain raft fraction [116] and in the white matter [114]. On the other hand, cholesterol levels were increased in nerve terminals of AD brains that were rich in amyloid aggregates [118] and in the core of mature, but not diffuse, amyloid plaques [119]. These observations suggest that amyloid-mediated sequestration of membranes, mainly in nerve terminals, may be one of the causes for cholesterol depletion from neuronal membranes in AD brains. Other causes of low cholesterol levels in AD brains may be APP-mediated inhibition of cholesterol synthesis [120], amyloid beta peptide-induced reduction of APOE-mediated cholesterol uptake [121], increased CYP46 activity leading to cholesterol oxidation and excretion [122,123] or beta amyloid-induced modifications of lipid rafts [124]. Increased CYP46 activity leading to cholesterol elimination could possibly be one of the multiple consequences of amyloid peptide-induced synaptic calcium alterations and oxidative stress [125,126]. These different possibilities are illustrated in Figure 3. In agreement with the observation that AD is accompanied by low brain cholesterol, low levels of cholesterol are also characteristic of the aging human brain in regions susceptible to the disease like the hippocampus [30,127–129], in Alzheimer's-like mice [130] and in hippocampal synapses of old mice [131]. In vitro studies have proposed that low neuronal membrane cholesterol levels might contribute to AD by a combination of events, including an increase in beta amyloid peptide production [132], a reduction in beta amyloid peptide degradation [133], an increase in the inflammatory response [134] and by facilitating the interaction of Aβ42 oligomers with lipid rafts, leading to plasma membrane perturbation, calcium dyshomeostasis, and toxicity [124,135]. In fibroblasts from Alzheimer's patients, recruitment of amyloid assemblies to the plasma membrane is higher in cholesterol poor conditions while high membrane cholesterol levels in these cells prevent Aβ42-induced generation of ROS and membrane lipoperoxidation [136].

Figure 3. Schematic picture showing how AD can lead to reduced cholesterol in neurons.

Numerous studies in brain samples from AD affected individuals show reduced cholesterol levels in structures like the hippocampus. In vitro studies suggest that amyloid oligomers, whether through binding to detergent resistant membrane domains (rafts) and/or in the form of amyloid peptide aggregates in intracellular compartments, trigger cell cholesterol decrease by various mechanisms: stress-activated Cyp46A1 transcription leading to cholesterol solubilization and excretion in the form of 24-OHC; sequestration of membranes and cholesterol within terminals from dying neurons and directly in amyloid plaques; inhibition of astrocyte-derived APOE-cholesterol uptake and/or by direct changes in plasma membrane lipid content. Cholesterol reduction can also occur in conditions accompanied by an excess of APP through direct inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR) and SREBP mRNA levels.

In summary, while it is quite clear that pharmacological reduction of cholesterol levels in cells with normal cholesterol content can inhibit amyloidogenic processing of over-expressed APP in a variety of cell types and systems [reviewed in 108], it remains unclear whether the conclusions from these studies can be extrapolated to the disease or normal aging contexts, especially taking into account the human studies showing that cholesterol levels are reduced in normal and pathological (Alzheimer's) aging brains (see Sidebar A). Given the numerous functions of cholesterol, it is not difficult to envision how reduced neuronal cholesterol levels can lead to brain dysfunction.

Brain cholesterol metabolism is altered by neurodegenerative pathologies and during aging

Significant changes in brain cholesterol metabolism have also been observed in other pathological conditions different from AD, such as Huntington's disease (HD), Parkinson's disease (PD), depression, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, stroke, head trauma, and also normal aging.

Aging is characterized by cognitive decline and is accompanied by altered short-term memory and learning. An age-dependent loss of cholesterol has been observed in the human brain [30,112,127–129] and in the rodent hippocampus, in vivo and in vitro [131,137]. At present, the causes for the age-associated cholesterol loss are not known. There are several candidate mechanisms. First, it could be due to increased transcriptional activation [125] and membrane mobilization [138] of the brain-specific cholesterol-hydroxylating enzyme Cyp46A1. This is supported by the observations that Cyp46A1 increases in high stress situations, such as cortical injury, induced autoimmune encephalomyelitis and in Alzheimer's disease [123,139,140]. Alternatively, the age-dependent lowering of cholesterol levels may be due to reduced synthesis in neurons or impaired delivery from glial cells.

Huntington's disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder caused by an abnormal expansion of a CAG repeat in the huntingtin gene resulting in behavioral abnormalities, cognitive decline, and involuntary movements. In HD patients, cholesterol metabolism in the brain is impaired [141,142] possibly by inhibition of SREBPs [141] by mutant huntingtin. Valenza and colleagues showed that cholesterol biosynthesis is reduced in brain samples from different transgenic mouse models expressing mutant huntingtin [143]. The authors also showed that cholesterol is first reduced in synaptosomes and later on in myelin and that transcript levels of genes mediating cholesterol biosynthesis and efflux are reduced in HD astrocytes causing lower production and secretion of APOE from these cells. Notably, these results are in contradiction with other studies showing increased free cholesterol in the same mice [144]. The divergence may be due to the use of different experimental approaches, namely mass spectrometry by Valenza et al [143] and filipin staining and thin-layer chromatography by Trushina et al [144]. Moreover, Valenza et al [141] perfused animals with saline before measurements of sterol levels in the brain, which may have reduced a substantial fraction of blood-derived cholesterol. Further support that mutant huntingtin affects cholesterol levels comes from in vitro experiments showing that the biosynthesis of cholesterol and fatty acids is impaired in cells expressing disease-causing mutants of huntingtin [141]. HD patients and HD mice show a progressive decrease of 24-OHC [142,143], which is a sign of neuronal cell loss. The decrease in this metabolite may further reduce cholesterol levels in the brain by impairing the activity of liver X receptors (LXRs), thus reducing expression of LXR-dependent transcripts like ABCA1 and APOE and consequently the transport of cholesterol to neuronal cells. Evidence for a role of the LXR pathway in HD—but not necessarily in ABCA1, APOE and cholesterol levels in the brain—comes from the observation that treatment with a LXR agonist partially reverts symptoms in a zebrafish model of HD [145].

Parkinson's disease (PD) is the second most common progressive neurodegenerative disorder after AD. Like in AD, a low number of PD cases are caused by mutations in specific genes: α-synuclein, parkin, LRRK2, PINK1, DJ-1, and ATP13A2 [146]. PD is characterized by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra of the midbrain and by the development of Lewy Bodies in neurons. Postmortem studies of highly purified lipid rafts from the frontal cortex of control, early motor stages PD, and incidental PD subjects did not reveal disease-related differences in the contents of sphingomyelin or cholesterol. However, the levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids were significantly reduced in raft fractions from PD compared to age-matched control subjects. Significant reductions were also observed in the fatty acid 18:1 (n-9) in combination with significant increases in stearic acid (18:0). The authors proposed that these changes could determine how cells respond to different forms of physical and/or chemical stress. However, confounding differences in dietary lipid uptake between patients and control subjects must be taken into account. On the other hand, acute manipulations of cholesterol in vitro suggest that cholesterol defects are not only a consequence of PD pathology but could contribute to PD. Treatment of cells and mice with the cholesterol-extracting drug methyl-β-cyclodextrin decreases the levels of α-synuclein in membrane fractions and reduces the accumulation of α-synuclein in the neuronal cell body and in synapses, preventing its aggregation [147]. However, the effects observed with cyclodextrins cannot be used to strongly argue that high cholesterol levels cause α-synuclein accumulation. First of all, it is unclear whether synuclein aggregation occurs in a background of high cellular cholesterol, and if so in which compartments. Second, and perhaps most critical, cyclodextrin represents a rather harsh treatment that not only leads to cholesterol extraction and redistribution to different membrane organelles but, due to its chemical nature, it can bind and redistribute other hydrophobic molecules (i.e. lipids) potentially affecting other pathways. On the other hand, also statins reduce the aggregation of α-synuclein in cultured neurons and in animal models of synucleinopathies [148,149], suggesting again that high cellular cholesterol could be at the base of this pathological sign. Yet, care should be taken when interpreting these results as (i) these data were obtained in cells and animals with normal and not high cholesterol levels, and (ii) statins play numerous HMG-CoA-independent roles, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory roles and also impact on the nitric oxide synthase pathway [150,151].

A dysregulation of brain cholesterol has been discussed in the context of other pathologic conditions including stroke, schizophrenia, depression, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, but again, it remains unclear whether the changes in brain cholesterol are at the base of these pathologies or are an epiphenomenon. A clear exception is spastic paraplegia type 5, a hereditary autosomal recessive disease with neurologic symptoms caused by mutations in CYP7B1 [152]. This enzyme is expressed in the brain and in the liver, where it hydroxylates 25- and 27-hydroxycholesterol to 7α-25-dihydroxycholesterol and 7α-27-dihydroxycholesterol. So far, it is unclear why its dysfunction causes progressive neuropathy in humans [153]. However, the strong increase in the substrate (27-hydroxycholesterol) in the CSF has been proposed to be the cause for the neurological symptoms [154].

In summary, the studies described above indicate that cholesterol metabolism in the brain is affected by various disease conditions. A major challenge for future research will be to determine the cellular origin (neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes) of disease-related changes in cholesterol levels, how each pathological condition affects cholesterol homeostasis in the brain, and whether cholesterol dyshomeostasis plays a causal role in the disease (see Sidebar A).

Mechanisms by which cholesterol dyshomeostasis could contribute to disease: role of oxysterols

Cells in the brain rely on constant cholesterol synthesis; however, the blood–brain barrier prevents entry and exit of lipoproteins. Consequently, cells in the brain require a specific mechanism to prevent an accumulation of excess cholesterol. Different mechanisms for removal of brain cholesterol are currently recognized [25,155–157]. An important one is the hydroxylation of cholesterol to 24-OHC by cholesterol 24-hydroxylase or CYP46 [25,28,157–159]. Interestingly, CYP46 is expressed specifically by neurons, suggesting that these cells are particularly sensitive to excess of cholesterol [31]. However, knockout mice lacking CYP46 do not present increased cholesterol levels, possibly due to the concomitant reduction in the cholesterol mevalonate pathway [160]. These mice exhibit severe deficiencies in spatial, associative, and motor learning, which are reversed by treatment with geranylgeraniol, a non-sterol isoprenoid required for learning, but not cholesterol. The explanation is that brains from mice lacking CYP46 excrete cholesterol more slowly, and the tissue compensates by suppressing the mevalonate pathway, which in turn results in lower synthesis of geranylgeraniol [160]. Geranylgeraniol is posttranslationally attached to a large number of proteins and regulates multiple cellular processes ranging from intracellular signaling to vesicular transport [161].

Cholesterol turnover catalyzed by CYP46 seems to be essential for neural function. Female homozygous transgenic mice that ubiquitously overexpress the cyp46A1 gene under the β-actin promoter present levels of circulating 24-OHC that are 30–60% higher than heterozygote littermates and show increased expression of synaptic proteins and improved spatial memory in the Morris water maze test, compared to wild-type mice [162]. Curiously, this effect was not observed in male mice, implying hormonal-dependent sensitivity to the effects of 24-OHC. It is unclear whether neuronal or glial cholesterol levels contribute to the improved cognition in these mice, as cholesterol levels were not measured in this model. Beneficial effects for CYP46 have also been proposed based on the evidence that increased cyp46A1 expression in the brain of APP23 mice by adeno-associated viral therapy significantly reduced Aβ pathology and gliosis and improved cognitive functions. These effects correlated with increased levels of 24-OHC in the brain regions under study, but no changes in total cholesterol levels were observed in these mice [163], suggesting that the effects may be unrelated to CYP46-mediated cholesterol removal from cells. In fact, oxysterols are not only intermediates in the cholesterol elimination pathway but also constitute important signaling molecules. 24-OHC serves as an activator of nuclear transcription factors, liver X receptors α and β [7,164], which increase the expression of cholesterol transport genes [165,166] including ABCA1 in both neurons and glia [167] and APOE in astrocytes [31,168]. ABCA1 mediates cellular cholesterol efflux in the brain and influences whole-brain cholesterol homeostasis. It has been shown in vitro that ABCA1 actively eliminates 24-OHC in the presence of HDL as a lipid acceptor and protects neuronal cells from the toxic effects of 24-OHC accumulation [169]. Previous studies showed that the exposure of SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells to physiological concentrations of 24-OHC led to a 90% loss in cell viability [170]. This last result is in contrast to the above-mentioned studies showing improved cognition and reduced amyloid load in mice with increased Cyp46A1 levels, leaving open the possibility that 24-OHC may produce different, even opposite, effects depending on levels and cell types.

Specific inactivation of ABCA1 in the mouse brain changes synaptic transmission and sensorimotor behavior [171]. Recent experiments in vivo showed that mice lacking brain ABCA1 exhibit cortical astrogliosis, increased inflammatory gene expression as well as activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) following acute lipopolysaccharide (LPS) administration. Mice lacking neuronal ABCA1 develop astrogliosis but show no change in inflammatory gene expression. These findings suggest that coordinated ABCA1 activity across neurons and glial cells influences neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration [172]. Accordingly, other experiments have shown that genetic elimination of either LXRα or β results in age-dependent neurodegenerative changes with accumulation of lipids in neurons, astrocytes, and the meninges [173].

Oxysterols may also modify Aβ peptide clearance by acting on the blood–brain barrier. 24-OHC and 27-hydroxycholesterol increased the expression of the ABCB1 transporter in brain capillary endothelial cells leading to enhanced Aβ clearance [174]. Moreover, oxysterols decrease Aβ peptide generation by brain capillary endothelial cells, by modulating the expression level of APP proteolytic enzymes [175] and possibly by changing the membrane cholesterol content of these cells [176]. Notably, 27-hydroxcholesterol is produced enzymatically in cells outside the nervous system, but it can enter the brain via the blood–brain barrier (Fig 2) [177], where it may signal the level of plasma cholesterol levels to cells in the brain and impact on the renin–angiotensin system [178]. This system in addition to its roles in salt and water homeostasis and the regulation of blood pressure regulates multiple brain functions such as learning and memory, processing of sensory information, and regulation of emotional responses [179].

Mechanisms by which cholesterol dyshomeostasis affects synaptic activity

Synaptic transmission appears to be particularly sensitive to a disturbance of cholesterol levels, probably because synaptic vesicle release at the presynaptic terminal and the response to signals through neurotransmitter receptors on the postsynaptic side rely entirely on membranous compartments and membrane-bound signaling pathways [180]. Some key aspects of cholesterol function in pre- and postsynaptic activities are schematized in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Proposed mechanism to explain how reduced brain cholesterol could underlie poor cognition.

In the presynaptic compartment, cholesterol depletion impairs synaptic vesicle exocytosis probably due to altered membrane curvature and impaired SNARE clusterization at fusion-competent sites. Cholesterol depletion also affects the ability of synapses to undergo sustained synaptic transmission by compromising the recycling of proteins from synaptic vesicles. In the postsynaptic compartment, cholesterol loss leads to MARCKS detachment from the membrane and PIP2 release. Most of the released PIP2 is transformed to PIP3 due to the enhanced TrkB PI3K activity also promoted by cholesterol loss. PIP3 accumulation stabilizes F-actin, blocks AMPARs at the dendritic spines, and also leads to high levels of active p-Akt, which in turn inactivates GSK3β required to promote AMPARs endocytosis. As a consequence of reduced PIP2, low PLCγ activity is also found in old neurons leading to impaired LTP. PLC activity is also required for processes such as actin depolymerization, AKAP150 removal from spines, and PSD95 degradation after LTD induction. Altogether, impaired LTP and LTD in old neurons result in decreased learning and memory.

Role of cholesterol in presynaptic vesicle fusion

For membrane fusion to occur, two bilayers must merge, resulting in extreme structural changes. Membrane curvature is a key determinant for fusion [181] and strongly depends on lipid composition and topology. The merging process between membrane bilayers requires a highly negative curvature [182], and thus, addition of lipids with negative intrinsic curvature facilitates the fusion of bilayers [183].

Cholesterol is a prominent component of synaptic vesicles. It supports intrinsic negative curvature of membranes [184,185] and facilitates the formation of high curvature intermediates during the fusion process. Depletion of cholesterol results in a dose-dependent inhibition of the rate and kinetics of fusion [186]. In addition, cholesterol may favor membrane fusion through its interaction with synaptophysin, an integral membrane protein enriched in synaptic vesicles [187]. Consistent with these data, cholesterol depletion impairs synaptic vesicle exocytosis in cultured neurons [188], greatly reduces Ca2+-evoked neurotransmitter release from synaptosomes [189], and alters presynaptic plasticity events [190]. Accordingly, addition of cholesterol to glia- and serum-free neuronal cultures enhances presynaptic transmitter release [191,192].

Furthermore, cholesterol may facilitate fusion by concentrating SNAREs, a highly conserved family of integral membrane proteins involved in synaptic vesicle fusion, at fusion-competent sites [189,193,194]. Cholesterol depletion also affects the ability of synapses to undergo sustained synaptic transmission [192] by compromising the recycling of SV proteins [195]. A thorough understanding of the presynaptic role of cholesterol probably requires more refined methods to manipulate its subcellular levels.

Influence of cholesterol on postsynaptic function

Changes in the number and composition of postsynaptic glutamate receptors contribute to the induction and consolidation of memory formation [196–199]. These changes occur through endocytosis and exocytosis but also through the rapid lateral diffusion of these receptors between synaptic and extrasynaptic areas in the plasma membrane [200,201]. These processes are controlled by receptor interactions with the underlying protein scaffold [202] and by the lipid composition of the subsynaptic membranes [24,203]. It has been shown that depletion of cholesterol destabilizes surface AMPA receptors clustered within lipid rafts in cultured hippocampal neurons [204] and decreases their mobility [203]. In agreement with these observations, we have recently shown that in neurons with low cholesterol levels, AMPA receptors accumulate at the cell surface due to reduced lateral mobility and impaired endocytosis [205], supporting the idea that cholesterol levels influence synaptic activity.

Similarly, the distribution and function of NMDA receptors depends on the lipid environment. Their presence in lipid rafts may facilitate their oligomerization [24]. Cholesterol depletion prevents NMDA-dependent Ca2+ influx in cultured hippocampal pyramidal cells [206] and inhibits NMDA-induced long-term potentiation (LTP) in the hippocampus [207]. Recent studies suggest 24-OHC as a very potent positive allosteric modulator of NMDARs. At sub-micromolar concentrations, 24-OHC potentiated NMDAR-mediated EPSCs in rat hippocampal neurons in vitro and enhanced the ability of sub-threshold stimuli to induce LTP in hippocampal slices. In turn, 24-OHC reversed hippocampal LTP deficits induced by the NMDAR channel blocker ketamine. Synthetic drug-like derivatives of 24-OHC are able to restore behavioral and cognitive deficits in rodents treated with NMDAR channel blockers [208].

Previous studies from our laboratory provide evidence for age-dependent changes in the membrane composition of rodent hippocampal neurons. We observed that the membrane concentration of the PI(4,5)P2-clustering molecule MARCKS declines during aging in mice hippocampal neurons. The reduced level of MARCKS lowers the concentration of PI(4,5)P2 and reduces PLCγ activity, with a negative impact on learning and memory [209]. More recently, we have shown that cholesterol depletion can trigger the detachment of MARCKS from neuronal membranes in culture, which suggests that the natural occurrence of cholesterol reduction during aging can contribute to the cognitive deficit phenotype of the elderly through, at least in part, this mechanism [205].

Our studies also suggest a link between cholesterol loss and TrkB receptor activation. First, age-related decrease of cholesterol in membranes of hippocampal neurons is accompanied by the recruitment of TrkB receptors to rafts and their phosphorylation in vivo and in vitro [137]. Second, mild (25%) reductions in membrane cholesterol of cultured neurons activate TrkB and its downstream effector Akt [137,210,211]. Age-dependent accumulation of active Akt occurred in the hippocampus of old mice [137,205,209], which could be restored by replenishment of cholesterol in hippocampal acute slices and in primary neurons with low cholesterol content [205,211]. Long-term depression (LTD) requires dephosphorylation of p-Akt to trigger endocytosis of AMPA receptors, and accumulation of p-Akt in old cells interferes with this process [205]. Electrophysiological recordings from brain slices of old mice and in anesthetized elderly rats demonstrated that the reduced hippocampal LTD associated with age can be rescued by cholesterol perfusion. Accordingly, cholesterol infusion in the lateral ventricle of old animals improved hippocampal-dependent learning and memory in the water maze test [205].

Therapeutic approaches to cholesterol-related brain diseases

Whether disturbances of cholesterol metabolism cause or contribute to brain disease, cholesterol and cholesterol-dependent pathways are obvious targets for therapeutic interventions.

A prime example for a potential therapeutic approach targeting cholesterol is provided by NPC disease. Several studies revealed that administration of a specific form of cyclodextrin can stop the progress of the disease in mouse models of NPC [212,213]. Although the exact mechanism is unknown, the most parsimonious explanation is that the lipophilic molecule equilibrates the cholesterol pools, by extracting cholesterol from sites where it is highly concentrated (such as the endosomal-lysosomal system) and redistributing it to sites with lower content (such as the plasma membrane). Irrespective of the unclear mode of action, a clinical trial exploring cyclodextrin as potential therapeutic approach to NPC patients is currently under way [214]. Interestingly, a recent study revealed that the same form of cyclodextrin has neuroprotective activity in cellular and mouse models of Alzheimer's disease [215].

A helpful indication for clinical trials is the availability of biomarkers that allow for monitoring treatment efficacy in a longitudinal manner. Again, NPC serves as an exemplary case, where progress has been made. Recent studies have shown that the plasma and CSF of NPC patients contain strongly elevated levels of specific oxysterols, namely 3β,5α,6β-cholestanetriol and 7-ketocholesterol that are generated by non-enzymatic oxidation [216]. These changes, which are probably caused by elevated oxidative stress in a variety of cell types, are highly specific and can be used to diagnose the disease and to monitor disease progression [217]. Future research should reveal whether these oxsterols can serve as biomarkers for other neurodegenerative diseases.

There is evidence that LXR activation by the agonist T0901317 reduces neuropathological changes and improves memory in mouse models of experimental dementia [218]. An essential role of LXRs for Aβ peptide clearance in the APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model has been proposed: activation of LXRs elevates the brain levels of APOE and ABCA1, resulting in increased amyloid clearance and markedly improved memory formation [219]. Similarly, LXR activation suppressed amyloid deposition and improved memory function in APP23 mice exposed to high fat diet [220], altogether suggesting that LXR activation can play different roles, at the central and systemic levels. It should be mentioned that astrocytic LXRα activation and subsequent release of APOE by astrocytes plays a role in cholesterol delivery to neuronal cells and has been shown to be critical for the ability of microglia to remove fibrillar Aβ in response to treatment with LRX activator TO901317 [221]. Note, however, that some LXR agonists are not very specific and may affect multiple molecular targets.

Statins have been assayed for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, ischemic stroke, and traumatic brain injury. However, the benefits of statins are controversial: some observations suggest that a positive relationship exists and that statins delay both, the onset and progression of dementia [76,222–224], others found a similar risk for dementia among statin and non-statin users [225] and some revealed cognitive impairment by statin treatment [226]. In January 2014, the United States Federal Drug Administration issued a note of advice on statin risks, recognizing the existence of cognitive impairment, such as memory loss, forgetfulness, insomnia, and confusion in some statin users (http://www.fda.gov/forconsumers/consumerupdates/ucm293330.htm). In agreement, a recent study showed that long-term oral treatment of mice with atorvastatin, the most widely prescribed statin, leads to significant alterations in behavior and cognition [227]. It is now thought that lipophilicity of the statins may determine the degree of side effects, especially those affecting muscle and central nervous system function, and could also explain the different results obtained in the different clinical trials [228]. It is in fact easy to envision that lipophilic statins can directly alter brain cholesterol levels, leading to dysfunction by the direct reduction of cholesterol in the membrane of astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes. In addition, one should not forget that statins may also exert beneficial effects through inhibiting the Cox-2 pathway and thus inflammation [229], by affecting the endothelial nitric oxide synthase [230] or by their anti-oxidant properties [231].

Conclusion

In summary, it is clear that a direct disturbance of cholesterol metabolism, for example, by defects in cholesterol synthesizing enzymes or transporters, impairs brain development and function. In addition, changes in cholesterol metabolism in the adult and during aging, and in several age-related neurodegenerative diseases, can directly impact on brain function. Nevertheless, a true causal link between brain cholesterol alterations and late-onset brain dysfunction and brain disease is unproven [232]. In fact, it even remains uncertain to which extent inheritable polymorphisms or mutations in cholesterol pathway genes predispose to brain pathology of the adult by a direct perturbation of brain cholesterol homeostasis rather than body cholesterol/metabolic dyshomeotasis indirectly affecting brain function. Like in AD, the changes in brain cholesterol in inherited conditions with symptoms in the adult could be an accompanying process, likely relevant in the stabilization or progression of disease signs, rather than being the cause of the disease. Further progress in the field requires careful cell-specific analyses of cholesterol homeostasis in neurons and glial cells under different pathologic conditions with new tools for cell-specific measurements and manipulations of cholesterol levels in vivo.

Sidebar A: In need of answers

For which of the major pathologies of the adult brain cholesterol dyshomeostasis is a primary disease-triggering event rather than simply a secondary effect of the disease, such as the multiple defects in cellular homeostasis that occur in the course of a disease (as for example mitochondrial dysfunction, calcium dyshomeostasis, transcriptional dysregulation)? It remains unclear whether polymorphisms in cholesterol synthesis and transport regulatory genes predispose to diseases of late onset like Alzheimer's due to a direct brain cholesterol defect or as a consequence of the accompanying vascular/systemic alterations (or the combination of both).

Can the levels of cholesterol-related biomarkers in blood or CSF of patients help to monitor patient-specific changes over time and to define disease progression?

Future transcriptional, protein, and lipid analyses should determine the cell types, such as neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, in which changes in cholesterol metabolism occur.

Should lipophilic, blood–brain barrier permeable, statins be used for the prevention or treatment of brain disorders? This is an important consideration for future clinical trials, in light of the numerous evidences for decreased cholesterol content and metabolism in the brains of the aged, and the reports (and formal warnings from the FDA) of cognitive and mood disorders in statin users.

Future studies should determine by which of its multiple sites of action statins produce ‘beneficial’ effects: through reduction of cellular cholesterol/cholesterol metabolites, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative stress, or the nitric oxide pathway?

Glossary

- 24-OHC

24S-hydroxycholesterol

- ABCA1

ATP-binding cassette transporter A1

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- AKAP150

A-kinase-anchoring protein 150

- Akt

serine/threonine kinase Akt/PKB (Protein kinase B)

- AMPARs

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors

- APOE

apolipoprotein E

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- CLU

Clusterin

- CNS

central nervous system

- Cox-2

cyclooxygenase 2

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- CYP46

cytochrome P450 cholesterol 24-hydroxylase

- CYP7B1

cytochrome P450 oxysterol 7-α-hydroxylase

- dhcr24

24-dehydrocholesterol reductase

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- EPSC

excitatory postsynaptic currents

- GWAS

genome-wide association studies

- HD

Huntington's disease

- HDL

high density lipoprotein

- HMG-CoA

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- LRRK2

leucin-rich repeat-kinase 2

- LTD

long-term depression

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- LXRs

liver X receptors

- MARCKS

myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate

- Mdm2

mouse double minute 2 homolog

- Mecp2

methyl CpG binding protein 2

- MβCD

methyl-β-cyclodextrin

- NMDAR

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

- NPC

Niemann-Pick C

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- PI(4,5)P2

phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate

- PINK1

PTEN-induced putative kinase 1

- PLCγ

phospholipase Cγ

- PSD95

postsynaptic density protein 95

- PUFAs

polyunsaturated fatty acids

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SLOS

Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome

- SNAREs

Soluble NSF Attachment Protein REceptors

- SREBPs

sterol regulatory element-binding proteins

- SV

synaptic vesicle

- T2DM

comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TrkB

tropomyosin-related kinase B receptor

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mañes S, Martínez-A C. Cholesterol domains regulate the actin cytoskeleton at the leading edge of moving cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:275–278. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dart C. Lipid microdomains and the regulation of ion channel function. J Physiol. 2010;588:3169–3178. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lippincott-Schwartz J, Phair RD. Lipids and cholesterol as regulators of traffic in the endomembrane system. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010;39:559–578. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simons K, Gerl MJ. Revitalizing membrane rafts: new tools and insights. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;10:688–699. doi: 10.1038/nrm2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levitan I, Singh DK, Rosenhouse-Dantsker A. Cholesterol binding to ion channels. Front Physiol. 2014;5:65. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLean KJ, Hans M, Munro AW. Cholesterol, an essential molecule: diverse roles involving cytochrome P450 enzymes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:587–593. doi: 10.1042/BST20120077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janowski BA, Grogan MJ, Jones SA, Wisely GB, Kliewer SA, Corey EJ, Mangelsdorf DJ. Structural requirements of ligands for the oxysterol liver X receptors LXRalpha and LXRbeta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:266–271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Björkhem I. Crossing the barrier: oxysterols as cholesterol transporters and metabolic modulators in the brain. J Intern Med. 2006;260:493–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radhakrishnan A, Ikeda Y, Kwon HJ, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Sterol-regulated transport of SREBPs from endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi: oxysterols block transport by binding to Insig. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6511–6518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700899104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill S, Chow R, Brown AJ. Sterol regulators of cholesterol homeostasis and beyond: the oxysterol hypothesis revisited and revised. Prog Lipid Res. 2008;47:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyoshi N, Iuliano L, Tomono S, Ohshima H. Implications of cholesterol autoxidation products in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;446:702–708. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.12.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg JM. The Complex Regulation of Cholesterol Biosynthesis Takes Place at Several Levels. Biochemistry. 5th edn. New York: W.H. Freeman; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lev S. Non-vesicular lipid transport by lipid-transfer proteins and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;10:739–750. doi: 10.1038/nrm2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikonen E. Cellular cholesterol trafficking and compartmentalization. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:125–138. doi: 10.1038/nrm2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Storch J, Xu Z. Niemann-Pick C2 (NPC2) and intracellular cholesterol trafficking. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:671–678. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. A proteolytic pathway that controls the cholesterol content of membranes, cells, and blood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11041–11048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mondal M, Mesmin B, Mukherjee S, Maxfield FR. Sterols are mainly in the cytoplasmic leaflet of the plasma membrane and the endocytic recycling compartment in CHO cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:581–588. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lingwood D, Simons K. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science. 2010;327:46–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1174621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Meer G. Dynamic transbilayer lipid asymmetry. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a004671. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gil C, Cubí R, Blasi J, Aguilera J. Synaptic proteins associate with a sub-set of lipid rafts when isolated from nerve endings at physiological temperature. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348:1334–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wasser CR, Kavalali ET. Leaky synapses: regulation of spontaneous neurotransmission in central synapses. Neuroscience. 2009;158:177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mailman T, Hariharan M, Karten B. Inhibition of neuronal cholesterol biosynthesis with lovastatin leads to impaired synaptic vesicle release even in the presence of lipoproteins or geranylgeraniol. J Neurochem. 2011;119:1002–1015. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki T. Lipid rafts at postsynaptic sites: distribution, function and linkage to postsynaptic density. Neurosci Res. 2002;44:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen JA, Halverson-Tamboli RA, Rasenick MM. Lipid raft microdomains and neurotransmitter signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:128–140. doi: 10.1038/nrn2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dietschy JM, Turley SD. Thematic review series: brain Lipids. Cholesterol metabolism in the central nervous system during early development and in the mature animal. Lipid Res. 2004;45:1375–1397. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R400004-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfrieger FW. Cholesterol homeostasis and function in neurons of the central nervous system. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1158–1171. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3018-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Björkhem I, Meaney S. Brain cholesterol: long secret life behind a barrier. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:806–815. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000120374.59826.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell DW, Halford RW, Ramirez DM, Shah R, Kotti T. Cholesterol 24-hydroxylase: an enzyme of cholesterol turnover in the brain. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:1017–1040. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.072407.103859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quan G, Xie C, Dietschy JM, Turley SD. Ontogenesis and regulation of cholesterol metabolism in the central nervous system of the mouse. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;146:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thelen KM, Falkai P, Bayer TA, Lütjohann D. Cholesterol synthesis rate in human hippocampus declines with aging. Neurosci Lett. 2006;403:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfrieger FW, Ungerer N. Cholesterol metabolism in neurons and astrocytes. Prog Lipid Res. 2011;50:357–371. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porter FD, Herman GE. Malformation syndromes caused by disorders of cholesterol synthesis. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:6–34. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R009548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanungo S, Soares N, He M, Steiner RD. Sterol metabolism disorders and neurodevelopment-an update. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2013;17:197–210. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanier MT. Niemann-Pick diseases. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;113:1717–1721. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-59565-2.00041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waterham HR, Hennekam RC. Mutational spectrum of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2012;160:263–284. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Barber AE, Eroglu Y, Merkens LS, Pappu AS, Steiner RD. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e24. doi: 10.1017/S146239941100189X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diaz-Stransky A, Tierney E. Cognitive and behavioral aspects of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2012;160:295–300. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nowaczyk MJ, Irons MB. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: phenotype, natural history, and epidemiology. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2012;160:250–262. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cunniff C, Kratz LE, Moser A, Natowicz MR, Kelley RI. Clinical and biochemical spectrum of patients with RSH/Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome and abnormal cholesterol metabolism. Am J Med Genet. 1997;68:263–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cooper MK, Porter JA, Young KE, Beachy PA. Teratogen-mediated inhibition of target tissue response to Shh signaling. Science. 1998;280:1603–1607. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koide T, Hayata T, Cho KWY. Negative regulation of Hedgehog signaling by the cholesterogenic enzyme 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase. Development. 2006;133:2395–2405. doi: 10.1242/dev.02393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Porter JA, Young KE, Beachy PA. Cholesterol modification of hedgehog signaling proteins in animal development. Science. 1996;274:255–259. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gallet A, Ruel L, Staccini-Lavenant L, Thérond PP. Cholesterol modification is necessary for controlled planar long-range activity of Hedgehog in Drosophila epithelia. Development. 2005;133:407–418. doi: 10.1242/dev.02212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zerenturk EJ, Sharpe LJ, Ikonen E, Brown AJ. Desmosterol and DHCR24: unexpected new directions for a terminal step in cholesterol synthesis. Prog Lipid Res. 2013;52:666–680. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klahre U, Noguchi T, Fujioka S, Takatsuto S, Yokota T. The Arabidopsis DIMINUTO/DWARF1 gene encodes a protein involved in steroid synthesis. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1677–1690. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.10.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schaller H. The role of sterols in plant growth and development. Prog Lipid Res. 2003;42:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(02)00047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu C, Miloslavskaya I, Demontis S, Maestro R, Galaktionov K. Regulation of cellular response to oncogenic and oxidative stress by Seladin-1. Nature. 2004;432:640–645. doi: 10.1038/nature03173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greeve I, Hermans-Borgmeyer C, Brellinger D, Kasper T, Gomez-Isla T, Behl C, Levkau B, Nitsch RM. The human DIMINUTO/DWARF1 homolog seladin-1 confers resistance to Alzheimer's disease-associated neurodegeneration and oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7345–7352. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07345.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crameri A, Biondi E, Kuehnle K, Lütjohann D, Thelen KM, Perga S, Dotti CG, Nitsch RM, Ledesma MD, Mohajeri MH. The role of seladin-1/DHCR24 in cholesterol biosynthesis, APP processing and Abeta generation in vivo. EMBO J. 2006;25:432–443. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vanier MT. Niemann-Pick disease type C. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patterson MC, Hendriksz CJ, Walterfang M, Sedel F, Vanier MT, Wijburg F. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Niemann-Pick disease type C: an update. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;106:330–344. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walkley SU, Suzuki K. Consequences of NPC1 and NPC2 loss of function in mammalian neurons. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1685:48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwon HJ, Abi-Mosleh L, Wang ML, Deisenhofer J, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Infante RE. Structure of N-terminal domain of NPC1 reveals distinct subdomains for binding and transfer of cholesterol. Cell. 2009;137:1213–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liscum L. Niemann-Pick type C mutations cause lipid traffic jam. Traffic. 2000;1:218–225. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vance JE, Karten B. Niemann-Pick C disease and mobilization of lysosomal cholesterol by cyclodextrin. J Lipid Res. 2014;55:1609–1621. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R047837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pentchev PG, Comly ME, Kruth HS, Vanier MT, Wenger DA, Patel S, Brady RO. A defect in cholesterol esterification in Niemann-Pick disease (type C) patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;8:8247–8251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lloyd-Evans E, Morgan AJ, He X, Smith DA, Elliot-Smith E, Sillence DJ, Churchill GC, Schuchman EH, Galione A, Platt FM. Niemann-Pick disease type C1 is a sphingosine storage disease that causes deregulation of lysosomal calcium. Nat Med. 2008;14:1247–1255. doi: 10.1038/nm.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lloyd-Evans E, Platt FM. Lipids on trial: the search for the offending metabolite in Niemann-Pick type C disease. Traffic. 2010;8:419–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liscum L, Ruggiero RM, Faust JR. The intracellular transport of low density lipoprotein-derived cholesterol is defective in Niemann-Pick type C fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1625–1636. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.5.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karten B, Vance DE, Campenot RB, Vance JE. Cholesterol accumulates in cell bodies, but is decreased in distal axons, of Niemann-Pick C1-deficient neurons. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1154–1163. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ko DC, Gordon MD, Jin JY, Scott MP. Dynamic movements of organelles containing Niemann-Pick C1 protein: NPC1 involvement in late endocytic events. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:601–614. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.3.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karten B, Campenot RB, Vance DE, Vance JE. The Niemann-Pick C1 protein in recycling endosomes of presynaptic nerve terminals. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:504–514. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500482-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vance JE, Hayashi H, Karten B. Cholesterol homeostasis in neurons and glial cells. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:193–212. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chahrour M, Jung SY, Shaw C, Zhou X, Wong ST, Qin J, Zoghbi HY. MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science. 2008;320:1224–1229. doi: 10.1126/science.1153252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Buchovecky CM, Turley SD, Brown HM, Kyle SM, McDonald JG, Liu B, Pieper AA, Huang W, Katz DM, Russell DW, et al. A suppressor screen in Mecp2 mutant mice implicates cholesterol metabolism in Rett syndrome. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1013–1020. doi: 10.1038/ng.2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Joshi HN, Fakes MG, Serajuddin ATM. Differentiation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors by their relative lipophilicity. Pharm Pharmacol Commun. 1999;5:269–271. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li Y, Wang H, Muffat J, Cheng AW, Orlando DA, Lovén J, Kwok SM, Feldman DA, Bateup HS, Gao Q, et al. Global transcriptional and translational repression in human-embryonic-stem-cell-derived Rett syndrome neurons. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:446–458. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel D, George-Hyslop PH, Pericak-Vance MA, Joo SH, Rosi BL, Gusella JF, Crapper-MacLachlan DR, Alberts MJ. Association of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1993;43:1467–1472. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schmechel DE, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Crain BJ, Hulette CM, Joo SH, Pericak-Vance MA, Goldgaber D, Roses AD. Increased amyloid beta-peptide deposition in cerebral cortex as a consequence of apolipoprotein E genotype in late-onset Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9649–9653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ordovas JM, Litwack-Klein L, Wilson PW, Schaefer MM, Schaefer EJ. Apolipoprotein E isoform phenotyping methodology and population frequency with identification of apoE1 and apoE5 isoforms. J Lipid Res. 1987;28:371–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lehtinen S, Lehtimäki T, Sisto T, Salenius JP, Nikkilä M, Jokela H, Koivula T, Ebeling F, Ehnholm C. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism, serum lipids, myocardial infarction and severity of angiographically verified coronary artery disease in men and women. Atherosclerosis. 1995;114:83–91. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)05469-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Howard BV, Gidding SS, Liu K. Association of apolipoprotein E phenotype with plasma lipoproteins in African-American and white young adults. The CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:859–868. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sparks DL, Scheff SW, Hunsaker JC, 3rd, Liu H, Landers T, Gross DR. Induction of Alzheimer-like beta-amyloid immunoreactivity in the brains of rabbits with dietary cholesterol. Exp Neurol. 1994;126:88–94. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zambón D, Quintana M, Mata P, Alonso R, Benavent J, Cruz-Sánchez F, Gich J, Pocoví M, Civeira F, Capurro S, et al. Higher incidence of mild cognitive impairment in familial hypercholesterolemia. Am J Med. 2010;123:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wolozin B, Kellman W, Ruosseau P, Celesia GG, Siegel G. Decreased prevalence of Alzheimer disease associated with 3-hydroxy-3-methyglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:1439–1443. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.10.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jick H, Zornberg GL, Jick SS, Seshadri S, Drachman DA. Statins and the risk of dementia. Lancet. 2000;356:1627–1631. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reed B, Villeneuve S, Mack W, DeCarli C, Chui HC, Jagust W. Associations between serum cholesterol levels and cerebral amyloidosis. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:195–200. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.5390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Altman R, Rutledge JC. The vascular contribution to Alzheimer's disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2010;119:407–421. doi: 10.1042/CS20100094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tenenholz Grinberg L, Thal DR. Vascular pathology in the aged human brain. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:277–290. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0652-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vasilevko V, Passos GF, Quiring D, Head E, Kim RC, Fisher M, Cribbs DH. Aging and cerebrovascular dysfunction: contribution of hypertension, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and immunotherapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;207:58–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05786.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.de la Torre JC. Is Alzheimer's disease a neurodegenerative or a vascular disorder? Data, dogma, and dialectics. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:184–190. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00683-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.de la Torre JC. How do heart disease and stroke become risk factors for Alzheimer's disease? Neurol Res. 2006;28:637–644. doi: 10.1179/016164106X130362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Newman AB, Fitzpatrick AL, Lopez O, Jackson S, Lyketsos C, Jagust W, Ives D, Dekosky ST, Kuller LH. Dementia and Alzheimer's disease incidence in relationship to cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1101–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Honig LS, Kukull W, Mayeux R. Atherosclerosis and AD: analysis of data from the US National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center. Neurology. 2005;64:494–500. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150886.50187.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bell RD. The imbalance of vascular molecules in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;32:699–709. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Orsucci D, Mancuso M, Ienco EC, Simoncini C, Siciliano G, Bonuccelli U. Vascular factors and mitochondrial dysfunction: a central role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2013;10:76–80. doi: 10.2174/156720213804805972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhiyou C, Yong Y, Shanquan S, Jun Z, Liangguo H, Ling Y, Jieying L. Upregulation of BACE1 and beta-amyloid protein mediated by chronic cerebral hypoperfusion contributes to cognitive impairment and pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem Res. 2009;34:1226–1235. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9899-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kitaguchi H, Tomimoto H, Ihara M, Shibata M, Uemura K, Kalaria RN, Kihara T, Asada-Utsugi M, Kinoshita A, Takahashi R. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion accelerates amyloid beta deposition in APPSwInd transgenic mice. Brain Res. 2009;1294:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Poli G, Sottero B, Gargiulo S, Leonarduzzi G. Cholesterol oxidation products in the vascular remodeling due to atherosclerosis. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Janson J, Laedtke T, Parisi JE, O′Brien P, Petersen RC, Butler PC. Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes. 2004;53:474–481. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kruit JK, Brunham LR, Verchere CB, Hayden MR. HDL and LDL cholesterol significantly influence beta-cell function in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21:178–185. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328339387b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ledesma MD, Dotti CG. Peripheral cholesterol, metabolic disorders and Alzheimer's disease. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;4:181–194. doi: 10.2741/e368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]