Abstract

Despite the fact that numerous major public health problems have plagued American Indian communities for generations, American Indian participation in health research traditionally has been sporadic in many parts of the United States. In 2002, the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma) and 5 Oklahoma American Indian research review boards (Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service, Absentee Shawnee Tribe, Cherokee Nation, Chickasaw Nation, and Choctaw Nation) agreed to participate collectively in a national research trial, the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescence and Youth (TODAY) Study. During that process, numerous lessons were learned and processes developed that strengthened the partnerships and facilitated the research. Formal Memoranda of Agreement addressed issues related to community collaboration, venue, tribal authority, preferential hiring of American Indians, and indemnification. The agreements aided in uniting sovereign nations, the Indian Health Service, academics, and public health officials to conduct responsible and ethical research. For more than 10 years, this unique partnership has functioned effectively in recruiting and retaining American Indian participants, respecting cultural differences, and maintaining tribal autonomy through prereview of all study publications and local institutional review board review of all processes. The lessons learned may be of value to investigators conducting future research with American Indian communities.

Keywords: American Indians, American Indian health, collaborative research, community-based research

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

American Indian communities have dealt with numerous public health–related issues for decades. Of all US racial/ethnic groups, the American Indian population continues to have the lowest attained levels of education, the highest unemployment rates, and the lowest income levels (1). American Indians have higher mortality rates, including mortality from tuberculosis, diabetes, and pneumonia, than all other US racial/ethnic groups (1).

Even with these health concerns, historically there have been significant barriers to conducting research with American Indian communities, including a lack of understanding of tribal culture, sovereignty, and research priorities by non-Native academic investigators (2–4). In some cases, American Indian communities have experienced abuse of trust, misinterpretation or misrepresentation of data, and failure by investigators to share new knowledge with them (2, 4–8). In other cases, academic researchers have ignored or failed to acknowledge valuable contributions made by tribal community members (8).

In the past, researchers entered American Indian communities with preconceived notions of the communities' problems, without knowledge of the culture or an appreciation of what the communities themselves viewed as their problems (4, 6, 8). At times, American Indian communities learned of studies' results only after seeing them in print or in the media, leading the communities to believe they were being exploited (4, 7, 8). Additionally, conflicts occurred when some investigators profited financially from the data collected while making no effort to share benefits with the participating communities (8). These issues have caused some tribal communities to resist participation in health research.

Such negative experiences have substantially hindered research efforts in Oklahoma, with a few notable exceptions (9–11). These studies, although successful examples of how research partnerships occur, still only provided examples of how to partner with individual tribal communities. Successfully partnering in research with all of Oklahoma's 39 American Indian tribal communities is a complex challenge (12), for reasons that include issues related to the complexity of tribal sovereignty, varying institutional review boards and health boards, and unique community issues, locations, identities, and concerns (2, 3). In this paper, we highlight a clinical trial that effectively overcame these barriers.

Tribal sovereignty

American Indian tribes and nations have a unique legal status known as tribal sovereignty. In the 1800s, the US Supreme Court recognized the ability of Native tribes and nations to regulate their own internal affairs but limited this power by recognizing them as domestic dependent nations (13). Tribal sovereignty is derived from complex and frequently changing treaties that were negotiated with the US government (6). The 1975 Indian Self-Determination Act, along with the passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act Amendments in 1988, allowed Native tribes and nations to take control of their health programs and reclaim traditional practices (14, 15). As a result of these acts and treaties, tribal sovereignty must be recognized and respected while partnering with American Indian tribes and nations in academic research (6).

Oklahoma tribal and Indian Health Service institutional review boards

As a result of previous concerns related to health research, many tribes have begun exerting their sovereign authority by developing tribal institutional review boards (IRBs) or research ethics boards that monitor research activities within their jurisdiction. In Oklahoma, 4 American Indian IRBs—the Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service IRB and 3 tribal IRBs, the Cherokee Nation, Chickasaw Nation, and Choctaw Nation IRBs—are registered and have their own unique Federalwide Assurance agreements with the Department of Health and Human Services' Office of Human Research Protection. The Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service and tribal IRBs provide human subject protections for the respective American Indian populations they serve, with the Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service IRB serving those tribes that do not have an IRB. Although these IRBs represent independent, sovereign entities, they often collaborate closely with one another.

Designed to promote research collaboration while preserving the rights of tribal citizens and protecting them from research harms, the boards also strive to protect tribal cultural values and sensitivities. The characteristics of tribal IRBs are unique, and these IRBs have a broader scope than a traditional academic IRB (7). American Indian IRBs typically: 1) require that approved research be relevant to tribal community priorities, 2) reserve the right to approve publications, and 3) claim sole or joint ownership of data generated by the research.

American Indian IRBs promote community-engaged research and work closely with the researchers throughout the duration of a project (16). Prior to conducting research with American Indian communities, investigators may be asked by the tribal IRB to complete cultural competency training to aid in the alignment with the community's values. The training helps bring equity to the relationship (6, 17, 18). Tribal IRBs may also recommend the designation of a tribal co-investigator to further solidify the establishment of a true partnership (2). In most instances, the additional investment of time and effort, done respectfully and properly, leads to the development of mutual trust, refinement of the research design, and community empowerment (8, 19).

BUILDING A COLLABORATIVE PARTNERSHIP: THE OKLAHOMA MODEL

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in the 1990s the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes increased by 71% among American Indians below the age of 35 years (20). Despite the fact that Oklahoma is home to one of the largest populations of American Indian people in the United States (20), many of whom are afflicted with diabetes, historically Oklahoma often has not been included in national diabetes research (10). Beginning in the late 1990s and early 2000s, researchers with the Department of Diabetes at the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma) met frequently with Oklahoma tribal leaders and members, in an effort to increase participation in meaningful diabetes research within American Indian communities. These meetings familiarized researchers with tribal customs, provided a better understanding of the communities' needs, and aided in the identification of potential risks and benefits of research. Communications with tribal leaders allowed for an exploration of ways to share resources and to provide much needed clinical services and program support.

Formal partnerships were established in 2000 whereby regular University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (OUHSC) pediatric diabetes services were provided on-site at tribal health-care facilities. During the provision of clinical services, OUHSC staff and tribal leaders identified 1 research issue of particular mutual interest and importance: developing better treatment for youth with type 2 diabetes. In 2002, the OUHSC, the Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service, and several Oklahoma tribes and nations agreed to participate in the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) Study. The TODAY Study, designed to determine optimal treatments in youth newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, was implemented at 15 clinical sites across the United States in May 2004 and will continue to follow the 699 enrolled youth until February 2020 (21).

Native American Coordinator

Learning from the few previous research collaborations in Oklahoma (9–11), the OUHSC and American Indian partners proposed the creation of a Native American Coordinator position as part of their National Institutes of Health TODAY Study grant application. The American Indian partners assisted the OUHSC with the interviewing and selection of the coordinator, whose proposed role was to foster relationships between the OUHSC and tribal communities and to ensure that American Indian interests were adequately represented in the TODAY Study. In addition, a concerted effort was made to hire American Indians, when possible, as TODAY Study employees. Ultimately, the positions of Native American Coordinator, Personal Activity and Nutrition Leaders, and Study Physician were filled by qualified American Indians. This strategy contributed in large part to the identification and screening of 63 Oklahoma American Indian youth with clinical type 2 diabetes for TODAY Study participation.

One of the first responsibilities of the Native American Coordinator was to facilitate Memoranda of Agreement (MOAs) between the OUHSC and American Indian partners (Figure 1). The research barriers previously experienced by other American Indian research partnerships encouraged the development of MOAs. The critical issues the MOAs addressed included acknowledgment of tribal sovereignty and preservation of research relevancy to the partnering communities. These agreements provided assurance that tribal customs and traditions would be respected and that research outcomes would be communicated to the American Indian communities. Once the MOAs had been signed, respective IRB and health board approvals were obtained before recruitment and enrollment could begin. Since American Indian participants were recruited throughout the state, approval from the Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service's IRB was also necessary.

Figure 1.

Site partners in the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) Study, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma (2004–present): the Absentee Shawnee Tribe, the Cherokee Nation, the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, the Chickasaw Nation, the Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service, the University of Oklahoma, the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine, and the TODAY Study. Reproduced with permission from the respective tribes, nations, and organizations.

Prereview of all presentations and publications

Another unique aspect of American Indian IRBs is the required review and approval of all research presentations and publications. The purpose of this requirement is not censorship but avoiding the repetition of historical missteps (17, 18). In addition, with careful prereview of publications and presentations, tribal nations ensure that participating communities learn about study findings prior to dissemination and ensure that scientific conclusions are presented accurately and in a culturally sensitive manner (1, 18, 19).

The TODAY Study MOAs with American Indian partners stated that the partnering IRBs would review all articles prior to publication. The TODAY Study leadership initially questioned the suitability of this requirement, voicing concerns that a separate review could delay the publication process. The fairness of allowing prereview of all publications was also questioned, since the TODAY Study investigators had not considered prepublication review for other minority groups and participation of American Indians would likely account for less than 10% of the study's cohort (21). Another concern was that sensitive, unpublished, or embargoed information might be leaked, thus jeopardizing publication. Finally, the question was raised as to how the TODAY Study would handle a potential American Indian IRB's refusal to allow publication.

Following her appointment to the TODAY Study Presentations and Publications (P&P) Committee, the Native American Coordinator proposed to the TODAY Study leadership and to American Indian partners a set of guidelines to ensure that all parties' concerns were addressed. The guidelines designated the Native American Coordinator as the liaison between the TODAY Study P&P Committee and the American Indian partners. It was agreed that the Native American Coordinator would be responsible for ensuring that all information would be held in strictest confidence, that partners would be fully informed, and that vetting would occur in a timely fashion. This resulted in the establishment of a TODAY Study Native American P&P Sub-Committee.

TODAY Study Native American P&P Sub-Committee

The formation of the TODAY Study Native American P&P Sub-Committee was unprecedented. A national research prereview committee comprised of representatives from numerous tribes/nations and a university had never been formed, and many people questioned how the committee might work. Sub-Committee members agreed to keep each reviewed manuscript draft in the strictest confidence until publication or presentation, and the Sub-Committee requested and agreed that no tribe-specific identifying data were to be analyzed or reported unless specifically requested by the tribes; however, individual participating tribes' and nations' names could appear in a manuscript's Acknowledgments section.

Currently, the TODAY Study Native American P&P Sub-Committee meets bimonthly. The Native American Coordinator reviews all TODAY Study presentations and publications, labels the materials according to the degree of review required, and then e-mails the items to all Sub-Committee members. Items not containing American Indian data are labeled “for your information only,” while items containing American Indian analyses are highlighted and designated as in need of immediate committee review. To ensure that the Sub-Committee's review process does not delay the national presentations and publications process, a time limit for a response or decision is assigned to each item. Decisions as to which reports are to be brought to the respective IRB/health board for review are made independently by each representative. If there is an IRB issue, the representative brings the concern back to the Sub-Committee. A majority vote decides which suggestion(s) will be made to the TODAY Study P&P Committee. Once the prereview has been concluded, the Native American Coordinator notifies the TODAY Study P&P Committee of any concerns identified.

In the last 4 years, the Sub-Committee has met approximately 40 times and has reviewed over 60 manuscript and presentation proposals. Only 2 items, each relating to data interpretation, have been identified by the TODAY Study Native American P&P Sub-Committee as matters of concern. On both occasions, the suggestions for alternate wording submitted by the Sub-Committee were reviewed, were accepted by the TODAY Study P&P Committee, and appeared in the final publications.

Another item the Native American P&P Sub-Committee addressed was whether prepregnancy educational material proposed as part of a small ancillary study during the follow-up of the TODAY Study was culturally appropriate for American Indian participants. After review and discussion, the Sub-Committee advised the OUHSC and the TODAY Study leadership that the proposed educational material was not an appropriate tool for their population, and they proposed alternate, culturally appropriate educational materials. The TODAY Study leadership agreed and approved the distribution of culturally appropriate educational materials to American Indian participants.

In addition to the prereview of all publications, the TODAY Study Native American P&P Sub-Committee has assisted in the streamlining of several TODAY Study IRB items. One example is the development and approval of a single consent form for all American Indian TODAY Study participants in the state; previously each IRB required its own unique form. In addition to its contributions to the TODAY project, the Sub-Committee's guidance has aided in the development of other academic and research partnerships. Representatives have provided counsel on potential projects, have helped researchers understand the complexity of American Indian tribal membership and health policies, and have provided a better understanding of the tribal IRB submission and navigation process. Conversely, regular contact with a diverse array of researchers through the subcommittee process provided American Indian partners an opportunity to evaluate and improve their own IRB policies and practices.

LESSONS LEARNED

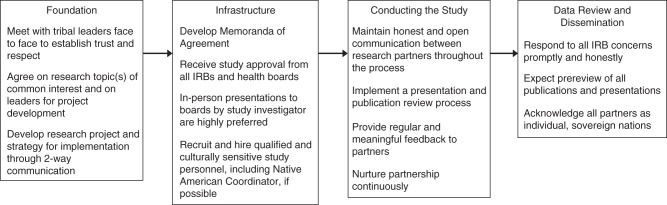

American Indian communities often view academic researchers in only one of 2 dichotomous ways: those who are genuinely invested in the communities and those who are not. Investment in tribal communities is demonstrated by meeting with American Indian leaders and community members early in the process, and it is an essential step in developing an effective partnership. Early and numerous conversations with tribal leaders likely will require extra time and compromise. Researchers must recognize that most American Indian communities have limited resources and competing priorities; as a result, investigators may encounter and should expect delays in implementation of projects. Recognition of tribal sovereignty is an elemental factor in any potential tribal partnership, and researchers should expect a requirement for prereview of all publications (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A suggested timeline for building a research partnership with American Indian tribes and nations. The length of time needed to complete each step may vary, timelines for different processes may overlap, and participants may need to return to various steps throughout the partnership process. IRB, institutional review board.

OUHSC researchers learned that there can be complex and lengthy legal issues involved when contracting with a tribe or nation and that one should anticipate a requirement for executing a legal instrument with a participating tribe or nation. To assist investigators who may be considering conducting research with these communities, the OUHSC and the American Indian partners created a list of the top 5 “hot-button” legal issues to consider when negotiating a legal instrument with a Native tribe or nation (Appendix). These are key issues to be aware of when negotiating MOAs with American Indian partners, including understanding of tribal jurisdiction, knowing who has the authority to enter into an agreement, the extent of data ownership, hiring/employment of American Indians, and reimbursement for expenses. American Indian tribes and nations may have similar items to consider when negotiating MOAs, but researchers must remember that each tribal entity negotiates and makes decisions regarding research entirely independently from other tribal entities.

Many concerns were alleviated and potential barriers ultimately resolved by the creation of the position of Native American Coordinator. The Coordinator assists in many of the functions necessary to maintaining open communication among partners. From serving on the national TODAY Study P&P Committee to providing well-monitored and highly protected access to pending presentations and publications, the Native American Coordinator aids in the process of open communication.

Finally, it should be noted that a new trend has emerged nationally in which tribes, nations, and collaborative institutions are developing “Data Use Agreements” (22, 23). American Indian tribes and nations assert that data obtained from their members belong to their people—in a sense, asserting “cultural property rights” (3, 22). A Data Use Agreement is considered an amicable option by which tribal ownership can be asserted even when the data are managed by another entity. This affords a tribe or nation legal protection against the potential risk of a data breach or the misuse of tribal information. While Data Use Agreements are now commonplace in the American Indian clinical trial community, the TODAY Study partnership was developed before the emergence of this issue. The American Indian partners and the OUHSC are currently considering developing a modified Data Use Agreement, potentially applicable for the continuation of the TODAY partnership.

CONCLUSIONS

The TODAY Study has provided an opportunity for the OUHSC and Oklahoma American Indian communities to engage in a collaboration, the extent of which is quite unique. In the process, the partnership developed into a singular, multitribal research association pursuing a common goal: meaningful research to address the diabetes epidemic facing American Indians in Oklahoma. With continued hard work and active, honest communication, the partnerships developed through the TODAY Study will foster future robust research relationships between American Indian communities, academic centers, and the National Institutes of Health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Section on Endocrinology, Department of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma (Jennifer Q. Chadwick, Kenneth C. Copeland, Mary R. Daniel); Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) Study, University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma (Jennifer Q. Chadwick, Kenneth C. Copeland, Mary R. Daniel); Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma (Julie A. Erb-Alvarez); Absentee Shawnee Tribe Shawnee Clinic, Shawnee, Oklahoma (Beverly A. Felton); Cherokee Nation Health Services, Tahlequah, Oklahoma (Sohail I. Khan); Section of Research and Population Health, Chickasaw Nation Department of Health, Ada, Oklahoma (Bobby R. Saunkeah); Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma Health Services Authority, Talihina, Oklahoma (David F. Wharton); Biostatistics Center, George Washington University, Washington, DC (Marisa L. Payan); and TODAY Study, George Washington University, Washington, DC (Marisa L. Payan).

This work was completed with funding from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health through grants U01-DK61212, U01-DK61230, U01-DK61239, U01-DK61242, U01-DK61254 and M01-RR14467 (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center).

We gratefully acknowledge the participation and guidance of the American Indian partners associated with the TODAY Study, including members of the Absentee Shawnee Tribe, the Cherokee Nation, the Chickasaw Nation, and the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, and the tribes supported by the Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service.

The content of this article and the opinions expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the respective tribal and Indian Health Service institutional review boards or their members.

K.C.C. is an advisor for a research study for Daiichi-Sankyo, Inc. (Parsippany, New Jersey) and receives an honorarium from the company.

APPENDIX

Top 5 Issues to Consider When Negotiating a Research Agreement With an American Indian Tribe or Nation

Jurisdiction and Venue. A standard agreement usually addresses jurisdiction and venue. Asking an American Indian nation to submit to state jurisdiction may not be feasible, and may be considered an insult. If your institution cannot agree to tribal jurisdiction or venue in tribal courts, then leave the issue silent.

Authority to Sign. It is the researcher's responsibility to determine who or which person or entity has the authority to obligate an American Indian tribe or nation. In addition, separate approvals from a governing body may have to be obtained, and a resolution, order, ordinance, or similar legal instrument may be required.

Data Ownership and Intellectual Property. A separate data use agreement may be the best way to address data ownership and intellectual property issues. These issues are complicated, and there are no easy answers. These issues should be addressed early.

Hiring American Indian Preference. Federal subcontracts usually require compliance with the policies of the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (http://www.eeoc.gov/). However, most American Indian tribes and nations are eligible for an exception under this law. This exception, under certain circumstances, allows for preference in hiring qualified American Indians, meaning that members of federally recognized tribes are given preference over other qualified applicants.

Indemnification. The principle of indemnification is a written guarantee from one party to protect and reimburse the other party for expenses associated with any loss or damage. For a research study, these would cover any losses or damages related to participation in the study. Will a sovereign nation indemnify an institution? The institution should be in a position to indemnify an American Indian tribe, because third parties (e.g., physicians) are routinely indemnified. If these issues cannot be agreed upon, then leave the issue silent.

REFERENCES

- 1.Division of Program Statistics, Indian Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services. Trends in Indian Health 2002–2003. Rockville, MD: Indian Health Service; 2004. http://www.ihs.gov/dps/files/Trends%20Cover%20Page%20&%20Front%20Text.pdf . Published January 25, 2010. Updated February 12, 2010. Accessed June 6, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis SM, Reid R. Practicing participatory research in American Indian communities. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(4 suppl):755S–759S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.4.755S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wax ML. The ethics of research in American Indian communities. Am Indian Q. 1991;15(4):431–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubin P. Indian givers: the Havasupai trusted the white man to help with a diabetes epidemic. Phoenix New Times. May 27, 2004. [online] http://www.phoenixnewtimes.com/2004-05-27/news/indian-givers/full/ Accessed November 7, 2012.

- 5.Valenti JM. Reporting hantavirus: a study of intercultural environmental journalism. Presented at the Conference on Communication and Environment; March 31–April 2, 1995; Chattanooga, Tennessee. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brugge D, Missaghian M. Protecting the Navajo People through tribal regulation of research. Sci Eng Ethics. 2006;12(3):491–507. doi: 10.1007/s11948-006-0047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foulks EF. Misalliances in the Barrow Alcohol Study. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 1989;2(3):7–17. doi: 10.5820/aian.0203.1989.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schell LM, Tarbell AM. A partnership study of PCBs and the health of Mohawk youth: lessons from our past and guidelines for our future. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106(suppl 3):833–840. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobson SF, Booton-Hiser D, Moore JH, et al. Diabetes research in an American Indian community. Image J Nurs Sch. 1998;30(2):161–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1998.tb01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoddart ML, Jarvis B, Blake B, et al. Recruitment of American Indians in epidemiologic research: the Strong Heart Study. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2000;9(3):20–37. doi: 10.5820/aian.0903.2000.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee ET, Begum M, Wang W, et al. Type 2 diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in American Indians aged 5–40: the Cherokee Diabetes Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(9):696–704. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bureau of Indian Affairs, US Department of the Interior. Indian entities recognized and eligible to receive services from the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs. Fed Regist. 2014;79(19):4748–4753. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 US 1, 16–17 (1831)

- 14. Indian Self-Determination Act of 1975, Pub. L. No. 93-638, 88 Stat. 2203, 25 USC §§450–458bbb-2 (1975)

- 15. Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act Amendments of 1988, Pub. L. No. 100-472, 25 USC §§450–450n (1988)

- 16.American Indian Law Center, Inc. Model Tribal Research Code: With Materials for Tribal Regulation for Research and Checklist for Indian Health Boards. 3rd ed. Albuquerque, NM: American Indian Law Center, Inc.; 1999. pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manson SM, Garroutte E, Goins RT, et al. Access, relevance, and control in the research process: lessons from Indian country. J Aging Health. 2004;16(5 suppl):58S–77S. doi: 10.1177/0898264304268149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Struthers R, Lauderdale J, Nichols LA, et al. Respecting tribal traditions in research and publications: voices of five Native American nurse scholars. J Transcult Nurs. 2005;16(3):193–201. doi: 10.1177/1043659605274984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christopher S, Watts V, McCormick AK, et al. Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1398–1406. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acton KJ, Burrows NR, Moore K, et al. Trends in diabetes prevalence among American Indian and Alaska Native children, adolescents, and young adults. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(9):1485–1490. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Copeland KC, Zeitler P, Geffner M, et al. Characteristics of adolescents and youth with recent-onset type 2 diabetes: the TODAY cohort at baseline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):159–167. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cochran PA, Marshall CA, Garcia-Downing C, et al. Indigenous ways of knowing: implications for participatory research and community. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):22–27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.093641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammed SA, Walters KL, LaMarr J, et al. Finding middle ground: negotiating university and tribal community interests in community-based participatory research. Nurs Inq. 2012;19(2):116–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2011.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]