Abstract

Purpose

To determine in vitro whether titanium is superior in corneal cell compatibility to standard polymethyl-methacrylate (PMMA) for the Boston Keratoprosthesis (KPro).

Methods

Human corneal-limbal epithelial (HCLE) cells were cultured 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144, or 168 hours in culture plates alone (controls) or with PMMA or titanium discs. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated (final n = 6). To determine if a soluble, toxic factor is emitted from materials, concurrent experiments at 48 and 144 hours were performed with discs placed in Transwell Supports, with HCLE cells plated beneath. As an additional test for soluble factors, cells were incubated 24 hours with disc-conditioned media, and number of viable cells per well was quantified at each timepoint by proliferation assay. To determine if delayed cell proliferation was attributable to cell death, HCLE cell death was measured under all conditions and quantified at each timepoint by cytotoxicity assay. The effects of material on HCLE cell proliferation over time was determined by repeated measures ANOVA. P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Results

HCLE cell proliferation was greater in wells with titanium discs compared to PMMA. Differences between the test discs and control non-disc cocultures were statistically significant over time for both cell proliferation (P = 0.001) and death (P = 0.0025). No significant difference was found using Transwells (P = 0.9836) or disc-conditioned media (P = 0.36).

Conclusion

This in vitro HCLE cell model demonstrates significantly increased cell proliferation and decreased cell death with cell/titanium contact compared to cell/PMMA contact. Moreover, differences are unlikely attributable to a soluble factor. Prospective in vivo analysis of the two KPro biomaterials is indicated.

Keywords: Boston Keratoprosthesis, biomaterials, titanium, corneal cell compatibility

INTRODUCTION

The Boston Keratoprosthesis (KPro) has continuously evolved over the past decade, with fewer complications and increasingly impressive results.1–3 This KPro is shaped as a collar-button and is made of polymethyl-methacrylate (PMMA). In 1992, it was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for marketing in the United States. It has since been primarily indicated for repeated graft failures, owing to the remarkably poor outcomes observed in patients with repeated corneal grafts.4 Design modifications and analyses of clinical outcomes have resulted in further optimizations of the Boston KPro. Among the modifications has been a backplate that snaps into place over the stem compared to the previous screw-on threaded models. Most recently, backplates have been machined out of titanium instead of conventional medical-grade PMMA. Use of titanium as a biomaterial is well established in orthopedic and dental prosthetics, attributable to its low density, relatively low-elastic (Young’s) modulus, superior biocompatibility, and enhanced corrosion resistance when compared to more traditional materials.5,6 Regardless of whether a backplate is PMMA or titanium, it is held in place with a titanium locking ring, exposing several corneal cell types to the material.

Although relatively benign, the tendency for KPro patients with a history of multiple operations to develop inflammation, retroprosthetic membranes (RPMs), and cellular debris (fibrin, collagen, etc.) within and around the PMMA backplate has been noted clinically. The formation of RPMs often leads to a need for repeated YAG-laser treatments, and the resulting fluctuant vision is often disconcerting for patients. More serious complications are rare but can occur, including retinal sequelae (eg, epiretinal membranes, cystoid macular edema, and even retinal detachment) or damage to the adjacent corneal tissues, leading to melt. Clinical impressions notwithstanding, no specific data exist comparing biomaterials for corneal prosthetics, particularly for the Boston KPro. Furthermore, it is unclear whether monomeric elements, cleaning or machining residues, or other toxic substances exude from the materials and consequently interact with corneal cells.7–9 Although the KPro backplates are in contact with the endothelium and are the first components of the KPro being tested as titanium, all the layers of the cornea have demonstrated clinical sequelae with the PMMA-only version. For example, neovascularization, retraction, necrosis, and melt have been observed around the KPro stem and at the surface epithelium.10,11 Titanium sheaths and other adaptations are being considered for the other parts of the Boston KPro, where they would be in contact with fibroblasts and epithelium. A readily available, well-characterized cell line, Human Corneal Limbal Epithelial (HCLE) cells, would provide us with important information about biomaterials and their effect on corneal physiology. The purpose of this experiment was, therefore, to determine whether titanium is superior with respect to corneal epithelial cell compatibility and proliferation to PMMA for the Boston KPro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Line

Immortalized HCLE cells were maintained at 37°C at 5% CO2 and grown as previously reported.12 Briefly, HCLE cultures were grown in keratinocyte serum-free medium (K-SFM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to prespecified timepoints, the final timepoint being confluence.

Experimental Design

Corneal cell compatibility with candidate ophthalmic device materials has been previously assayed using in vitro experiments in which cells are cultured either in direct contact with materials or in material-conditioned media.13–18 For studies reported here, HCLE cells were plated at equivalent cell density in wells containing a titanium disc, a PMMA disc, or no disc (controls). The discs, which were prepared per the normal KPro cleaning and manufacturing protocol,13 were similar in size and dimension to the KPro backplates. HCLE cells were cultured for 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144, or 168 hours. To determine if a soluble, toxic factor was being emitted from the materials, a concurrent experiment was performed at 48 and 144 hours, placing the discs in Transwell Permeable Supports (3.0-μm pore size; CoStar, Corning, NY), with the HCLE cells plated beneath. The number of viable cells per well for all experiments was quantified at each timepoint, using Cell Titer 96 AQueous One Solution Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI), which assays dehydrogenase enzymes in metabolically active cells. To determine if cell proliferation was being delayed by cell death, a similar experiment was conducted by measuring HCLE cell death in control, PMMA, and titanium conditions at the same 7 time-points. Cell death was quantified at each timepoint by using the Cytotox 96 nonradioactive cytotoxicity assay (Promega), which assays lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) that is released into culture media upon cell death. All experiments were done in triplicate and repeated for a final sample number of 6.

To further assess the validity of using Transwell culture as a test for a soluble toxic factor, media (K-SFM) were collected after either a 48-hour incubation with PMMA or titanium discs or media alone (control) (n = 5). The 48-hour timepoint was used because observations from earlier experiments indicated that the greatest HCLE cell death occurred during the initial 48 hours of plating. The disc-conditioned media were used to feed the HCLE cells after an initial 24 hours of culture.

The Cytotox 96 cytotoxicity assay was run on media taken after an initial 24 hours of culture (controls) and then again on disc-conditioned media taken at 48 hours from the same cultures.

Statistical Analyses

A repeated measures ANOVA with SAS version 9.1 was used to determine the effects of material over time on HCLE cell proliferation. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

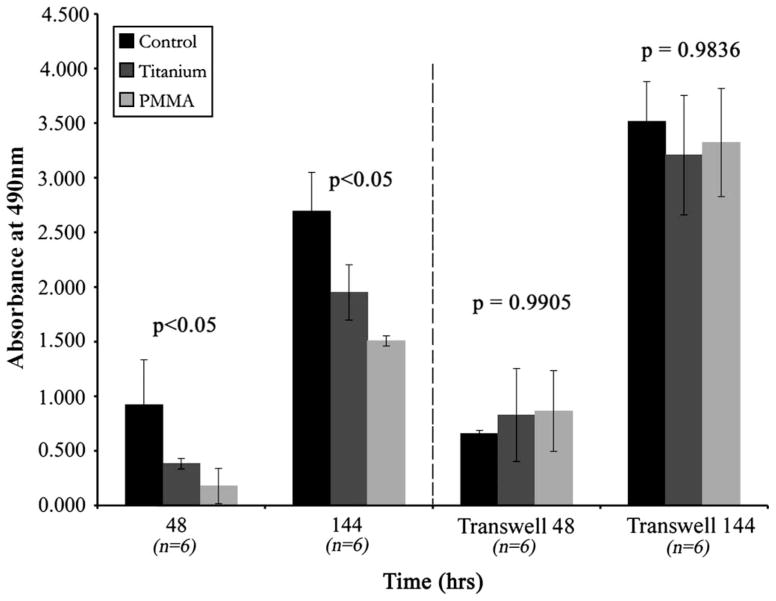

HCLE cell proliferation in wells with either titanium or PMMA discs was delayed and was less than that observed in control wells. The effect on cell proliferation of exposure of epithelial cells to the two disc types or non-disc cultured controls was statistically significant (P < 0.001) by repeated measures ANOVA; the most proliferation was seen in the control group, followed by that in the titanium group, and finally the PMMA group. Mean proliferation ± SD and exponential trend lines are illustrated in Figure 1. Cell proliferation in the wells with titanium discs was greater than in those with PMMA discs up to the 120- hour timepoint (P < 0.01). At 144 hours, this difference lost significance (P = 0.5917). Actual values for HCLE cell proliferation are given as percent of control ± SD percent in Table 1. The results from the Transwell experiment designed to determine if a soluble factor from the discs impeded cell proliferation are shown in Figure 2. HCLE cells grown in Transwell culture with the discs in the upper chamber did not demonstrate a significant difference in proliferation irrespective of the conditions (control, PMMA, or titanium) at 48 or 144 hours (P = 0.9905 and P = 0.9836, respectively).

FIGURE 1.

Human corneal-limbal epithelial (HCLE) cell proliferation over 168 hours in 3 different conditions: control, with polymethyl-methacrylate (PMMA), and with titanium. Data are given as mean cell growth ± SD. Repeated Measures ANOVA analysis indicated a significant effect for material × time for HCLE cell proliferation in this study (P < 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Percentage of Viable HCLE Cells in PMMA and Titanium Wells Compared to Control Wells

| Timepoint (hours) | PMMA | Titanium |

|---|---|---|

| 24 | 25 ± 23% | 62 ± 23% |

| 48 | 26 ± 16% | 53 ± 9% |

| 72 | 14 ± 16% | 57 ± 14% |

| 96 | 4 ± 5% | 52 ± 34% |

| 120 | 2 ± 3% | 83 ± 7% |

| 144 | 46 ± 27% | 67 ± 28% |

| 168 | 24 ± 25% | 72 ± 14% |

Data are presented as percent of control ± SD percent.

FIGURE 2.

Human corneal-limbal epithelial (HCLE) cells grown in normal wells (left) and Transwells (right) at 48 and 144 hours in control, polymethyl-methacrylate (PMMA), and titanium conditions. Data are given as mean cell growth ± SD. HCLE cells grown using Transwells did not demonstrate a significant difference in proliferation, irrespective of the condition.

HCLE cell death was measured with a Promega cyto-toxicity assay over 7 timepoints for each of the experimental conditions. Exponential trend lines in addition to mean data ± SD are shown in Figure 3. HCLE cell death in wells with PMMA occurred earlier and was greater than in wells of either the control or the titanium group. A repeated measures ANOVA indicated a significant overall effect for material over time for HCLE cell death (P < 0.0025). HCLE cell death did occur in both the control and titanium groups, but to a lesser degree than that in the PMMA group. Difference in HCLE cell death over time between PMMA and titanium was also statistically significant (P = 0.0043), whereas the difference in death over time between titanium and control was not (P = 0.42).

FIGURE 3.

Cytotoxic assay to measure human corneal-limbal epithelial (HCLE) cell death over 168 hours in control, with polymethyl-methacrylate (PMMA) and with titanium. Cell death in wells with PMMA occurred earlier and was greater than that in the control or titanium groups. Repeated measures ANOVA indicated a significant effect for material × time for HCLE cell death in this study (P < 0.01).

In all experiments, HCLE cells in the control group reached confluence on average at 144 ± 18 hours, whereas HCLE cells in the PMMA and titanium groups were delayed, reaching confluence on average at 212 ± 18 hours and 172 ± 18 hours, respectively.

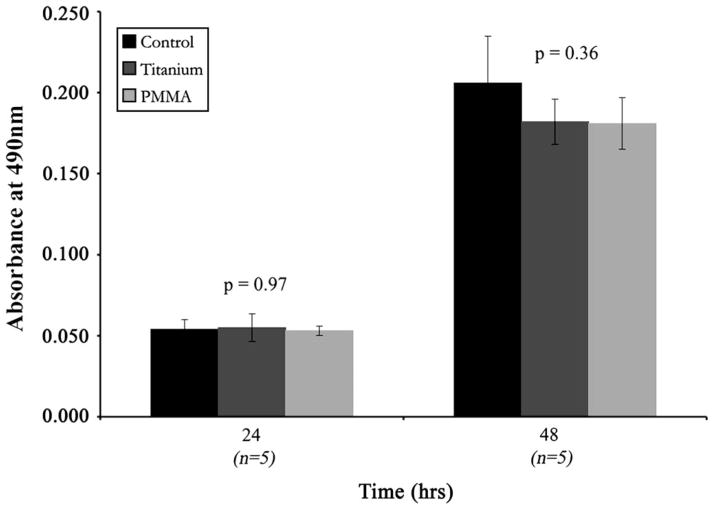

As a second assay to determine if a soluble factor eluting from the discs induced cell death, cells were cultured with disc-conditioned media (Figure 4). Differences in HCLE cell death among the control, PMMA-conditioned, and titanium-conditioned wells were not significant at 48 hours (P = 0.36), corroborating the co-culture experiments using the Transwell plate.

FIGURE 4.

Human corneal-limbal epithelial (HCLE) cell death at 24 hours in normal media and at 48 hours with disc-conditioned growth media. Data are given as mean cell death ± SD. ANOVA indicated that the amount of HCLE cell death in the control wells, polymethyl-methacrylate (PMMA)–conditioned wells, and titanium-conditioned wells did not differ significantly at 48 hours (P = 0.36).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine whether titanium demonstrated corneal cell compatibility superior to that of conventional PMMA for the Boston Keratoprosthesis (KPro). For this purpose, machined PMMA and titanium discs were prepared using the same specifications and cleaning protocols used with the KPro. HCLE cell proliferation with titanium discs was found to be superior to that with PMMA discs, and proliferation in control wells was superior to that in either of the disc-conditioned wells. Furthermore, results from both Transwell and conditioned-media experiments suggest that differences in growth are not attributable to a soluble toxic factor. It appears, therefore, that the machining and cleaning of the devices are effective and that no residues from either of the processes are a factor. It remains unknown whether increases in HCLE cell death on PMMA discs are due to surface contact issues, electrostatic forces, monomeric components, or some undetermined characteristic of the materials. It is clear, however, that the effect is contact-associated; in Transwell and disc-conditioned cultures, decreased proliferation and increased cell death are not evident, respectively.

PMMA and titanium have been used for dental and orthopedic prosthetics for decades.5,6,19–22 PMMA is often lauded for its ability to be molded, whereas titanium is noted for its low density and enhanced corrosion resistance.5 However, there have been few studies comparing the two biomaterials. One, a randomized, controlled study by Schröder et al, investigated the vertebral fusion rates and clinical outcomes, comparing PMMA to titanium in their roles as nonautologous, interbody fusion materials.23 Their findings were consistent with the results presented in this paper. Where we found that titanium was superior to PMMA in terms of corneal epithelial cell compatibility, the Schröder et al study found titanium superior to PMMA with respect to vertebral fusion rate. They also concluded that this difference was inconsequential, however, because no benefit with titanium was observed with respect to the clinical outcome. A second study sought to evaluate the biocompatibility of carbon and titanium surface modified, PMMA Intraocular Lens (IOL) in a pseudophakic rabbit model.24 In this study, white blood cell concentration in the aqueous humor was significantly lower in the carbon and titanium IOL-implanted eyes compared with PMMA IOL-implanted eyes. They also found that the exudate levels in the anterior ocular chamber and the posterior synechias were significantly lower in the titanium group alone. To the authors’ knowledge, there are no published papers reporting titanium’s superiority to PMMA as a biomaterial in the cornea.

There are two limitations to the study. First, it is an indirect in vitro measure of biocompatibility; therefore, the results cannot be extrapolated directly to the patient population. Second, as alluded to above, the KPro backplate is currently the only component machined out of titanium and is in contact with the endothelium in vivo, not the epithelium, as measured here. Large numbers of cell culture experiments were needed for this study, requiring immortalized cell lines. Immortalized HCLE cells are readily available for research, whereas endothelial cells are not, making endothelial assay not feasible. Furthermore, the applications for titanium use in other components of the KPro are being considered, in which epithelium and stromal cells will be in contact with the material. Data from the epithelial cell culture are relevant to other cell types because the toxicity and proliferation assays are employed universally for all cell types.

The findings reported in this study may have important clinical implications for the Boston KPro and may support the move towards titanium backplates in patients or feasibly a titanium sheath around areas that are in contact with the epithelium (the front plate and stem). Prospective in vivo analyses of the two KPro biomaterials, with the potential for other surfaces as well, are being conducted.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by Dr. Claes Dohlman’s keratoprosthesis research fund, in which he (CD) has no commercial or financial interest.

References

- 1.Dohlman C, Harissi-Dagher M, Khan B, et al. Introduction to the use of the Boston Keratoprosthesis. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2006;1:41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zerbe BL, Belin MW, Ciolino JB. Results from the multicenter Boston Type 1 Keratoprosthesis Study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1779, e1771–e1777. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan BF, Harissi-Dagher M, Khan DM, et al. Advances in Boston keratoprosthesis: Enhancing retention and prevention of infection and inflammation. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2007;47:61–71. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e318036bd8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bersudsky V, Blum-Hareuveni T, Rehany U, et al. The profile of repeated corneal transplantation. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:461–469. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00544-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long M, Rack HJ. Titanium alloys in total joint replacement–a materials science perspective. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1621–1639. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morra M, Cassinelli C. Biomaterials surface characterization and modification. Int J Artif Organs. 2006;29:824–833. doi: 10.1177/039139880602900903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piver WT. Diffusion of residual monomer in polymer resins. Environ Health Perspect. 1976;17:227–236. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7617227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peng C. Determination of residual monomer in polymer or polymer solution by sealed glass capillary sampling. Chromatographia. 1989;28:167–169. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lung CY, Darvell BW. Minimization of the inevitable residual monomer in denture base acrylic. Dent Mater. 2005;21:1119–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dudenhoefer EJ, Nouri M, Gipson IK, et al. Histopathology of explanted collar button keratoprostheses: a clinicopathologic correlation. Cornea. 2003;22:424–428. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200307000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harissi-Dagher M, Khan BF, Schaumberg DA, et al. Importance of nutrition to corneal grafts when used as a carrier of the Boston Keratoprosthesis. Cornea. 2007;26:564–568. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318041f0a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gipson IK, Spurr-Michaud S, Argueso P, et al. Mucin gene expression in immortalized human corneal-limbal and conjunctival epithelial cell lines. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2496–2506. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werner L, Legeais JM, Nagel MD, et al. Neutral red assay of the cytotoxicity of fluorocarbon-coated polymethylmethacrylate intraocular lenses in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;48:814–819. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(1999)48:6<814::aid-jbm8>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langefeld S, Volcker N, Kompa S, et al. Functionally adapted surfaces on a silicone keratoprosthesis. Int J Artif Organs. 1999;22:235–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chirila TV, Walker LN, Constable IJ, et al. Cytotoxic effects of residual chemicals from polymeric biomaterials for artificial soft intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1991;17:154–162. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chirila TV, Thompson DE, Constable IJ. In vitro cytotoxicity of melanized poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) hydrogels, a novel class of ocular biomaterials. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 1992;3:481–498. doi: 10.1163/156856292x00457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tripathi BJ, Tripathi RC, Millard CB, et al. Cytotoxicity of hydrogen peroxide to human corneal epithelium in vitro and its clinical implications. Lens Eye Toxici Res. 1990;7:385–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang HZ, Chang CH, Lin CP, et al. Using MTT viability assay to test the cytotoxicity of antibiotics and steroid to cultured porcine corneal endothelial cells. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1996;12:35–43. doi: 10.1089/jop.1996.12.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frick C, Dietz AC, Merritt K, et al. Effects of prosthetic materials on the host immune response: evaluation of polymethyl-methacrylate (PMMA), polyethylene (PE), and polystyrene (PS) particles. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2006;16:423–433. doi: 10.1615/jlongtermeffmedimplants.v16.i6.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yilmaz A, Baydas S. Fracture resistance of various temporary crown materials. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2007;8:44–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skoglund B, Aspenberg P. PMMA particles and pressure—A study of the osteolytic properties of two agents proposed to cause prosthetic loosening. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:196–201. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00150-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernandez EP, Oshida Y, Platt JA, et al. Mechanical properties of four methylmethacrylate-based resins for provisional fixed restorations. Biomed Mater Eng. 2004;14:107–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schroder J, Grosse-Dresselhaus F, Schul C, et al. PMMA versus titanium cage after anterior cervical discectomy— A prospective randomized trial. Zentralbl Neurochir. 2007;68:2–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-942184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan Z, Sun H, Yuan J. A1-year study on carbon, titanium surface-modified intraocular lens in rabbit eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exper Ophthalmol. 2004;242:1008–1013. doi: 10.1007/s00417-004-0970-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]