Abstract

Background

We previously identified an ECF sigma factor, σS, that is important in the stress and virulence response of Staphylococcus aureus. Transcriptional profiling of sigS revealed that it is differentially expressed in many laboratory and clinical isolates, suggesting the existence of regulatory networks that modulates its expression.

Results

To identify regulators of sigS, we performed a pull down assay using S. aureus lysates and the sigS promoter. Through this we identified CymR as a negative effector of sigS expression. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) revealed that CymR directly binds to the sigS promoter and negatively effects transcription. To more globally explore genetic regulation of sigS, a Tn551 transposon screen was performed, and identified insertions in genes that are involved in amino acid biosynthesis, DNA replication, recombination and repair pathways, and transcriptional regulators. In efforts to identify gain of function mutations, methyl nitro-nitrosoguanidine mutagenesis was performed on a sigS-lacZ reporter fusion strain. From this a number of clones displaying sigS upregulation were subject to whole genome sequencing, leading to the identification of the lactose phosphotransferase repressor, lacR, and the membrane histidine kinase, kdpD, as central regulators of sigS expression. Again using EMSAs we determined that LacR is an indirect regulator of sigS expression, while the response regulator, KdpE, directly binds to the promoter region of sigS.

Conclusions

Collectively, our work suggests a complex regulatory network exists in S. aureus that modulates expression of the ECF sigma factor, σS.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12866-014-0280-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Sigma factor, Regulation, Mutagenesis

Background

Staphylococcus aureus is an exceedingly virulent and successful pathogen, capable of causing a wide range of infections, from relatively benign skin lesions to life threatening septicemia. With an overwhelming ability to adapt to its environment, S. aureus has become the most common cause of both hospital and community acquired infections, and is believed to be the leading cause of death by a single infectious agent in the United States [1,2]. The threat posed by this organism to human health is further heightened by the rapid and continued emergence of multi-drug resistant isolates [1-4]. The success of S. aureus as a pathogen can, in part, be attributed to its many immune-evasion strategies, mediated by secreted and surface-associated virulence determinants. These virulence determinants have multi-faceted roles, allowing for adhesion, immune subversion and dissemination.

The regulation of gene expression is a fundamental property to all living systems that allows them to adapt and respond to different environmental conditions. Regulation can occur at the level of transcription, translation and post-translation, with the primary point being at the level of transcription. In bacteria, transcription is catalyzed by RNA polymerase (RNAP) whose promoter recognition and selectivity is influenced by a variety of transcription factors, with the most important group being sigma factors. In order for prokaryotes to initiate transcription, a sigma factor is required to associate with core RNAP. Once associated, sigma factors play a role in promoter recognition, and promoter melting to form the transcriptional open complex. All prokaryotes have a primary sigma factor, σA, which mediates transcription of the majority of genes, including those with housekeeping functions (e.g. replication machinery, cell division). In addition to this, alternative sigma factors exist, which control subsets of genes that are involved in specialized cellular functions or stress responses (e.g. oxidative stress, heat shock, etc.) [5]. In 1994, Lonetto et al. described a subfamily of alternative sigma factors known as extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors; and over the past two decades there has been a large number of these elements identified [5-7]. Indeed, ECF sigma factors now represent the most numerate sub-family of these enzymes, with many bacteria possessing multiple such factors; so that this group outnumbers all other types of alternative sigma factors combined [5]. In addition to their growing number, their role in virulence is become increasingly apparent. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, ECF sigma factors play an important role in iron uptake pathways, alginate secretion, and the expression of virulence factors, all of which contribute to pathogenesis. With such a complex life style, it would not be surprising if several ECF sigma factors were present in the genome of S. aureus. However, to date, only one has been identified, σS, which forms the basis of this work [7].

Our group has previously shown that purified σS is able to bind core-RNAP and initiate transcription from its own promoter. A sigS mutant was found to be more sensitive to lysis by Triton X-100, and is outcompeted in long-term growth experiments by the parent under both standard conditions and in the presence of chemical stressors. Using a murine model of septic arthritis, it was also found that sigS is required for full virulence of S. aureus [7]. More recently, our group demonstrated that sigS expression is not observed under standard conditions except in the highly mutated strain, RN4220 [8]. However, sigS expression is induced in the presence of a number of chemical stressors that include DNA damaging and cell wall targeting agents. In addition, this element is upregulated upon challenge by components of the immune system, and during phagocytosis by murine macrophage-like cells [8].

The control of alternative sigma factor expression has been increasingly documented, with a number of novel genetic regulatory mechanisms identified [9,10]. A recent study regarding sigH in S. aureus, demonstrates that the expression of this element can only be induced by a chromosomal gene duplication rearrangement that occurs spontaneously, generating a new chimeric sigH gene driven by the promoters of either nusG or rplK [9]. A second, post-transcriptional mechanism of regulation also occurs, through an upstream inverted repeat that suppresses the translation of σH protein [9]. With regards to the regulation of ECF sigma factors, a number of studies have described unique mechanisms of regulation, including for an ECF sigma factor that is closely related to σS, σM of B. subtilis. In a recent study it was shown that inactivation of a conserved membrane protein, yfhO, leads to an increase in activity of a putative bactoprenol glycosyltransferase. This subsequently leads to activation of σM [10], as the shortage of available bactoprenol impacts cell envelope integrity, which σM is believed to play a role in protecting [11].

In this study we expand on our previous work exploring the environmental induction of sigS expression in S. aureus, by focusing at the genetic level, so as to understand the regulatory circuits involved in controlling the expression of this gene.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

S. aureus and E. coli strains, along with plasmids and primers, are listed in Table 1. E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. S. aureus was grown in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm, unless indicated otherwise. Synchronized cultures were obtained as previously describe [7]. When required, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: ampicillin 100 μg ml−1, tetracycline 5 μg ml−1, erythromycin 5 μg ml−1, lincomycin 25 μg ml−1, and 0.25 mM cadmium chloride. Where specified, agar plates contained the DNA damaging agent methyl methanesulfonate at a concentration of 0.25 mM.

Table 1.

Strains, plasmids and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid or primer | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | φ80 Δ(lacZ)M15 Δ(argF-lac)U169 endA1 recA1 | [12] |

| hsdR17 (rK −mK +) deoR thi-1 supE44 gyrA96 relA1 | ||

| S. aureus | ||

| RN4220 | Restriction deficient transformation recipient | Lab stocks |

| 8325–4 | Wild-Type Laboratory Strain rsbU mutant | Lab stocks |

| SH1000 | Wild-Type Laboratory Strain rsbU functional | [13] |

| LES57 | SH1000 pAZ106::sigS-lacZ sigS + | 7 |

| HKM08 | 8325–4 pAZ106::sigS-lacZ sigS + | This study |

| HKM15 | LES57 isolate subject to random mutagenesis using nitrosoguanidine | This study |

| HKM16 | LES57 isolate subject to random mutagenesis using nitrosoguanidine | This study |

| HKM17 | 8325–4 pSC-A::tet::sigS-lacZ sigS + | This study |

| HKM18 | 8325–4 pSC-A::tet::sigS-lacZ sigS + pRN3208 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSC-A | TA clone vector lacking Gram-positive origin of replication | Strata clone |

| pRN3208 | TS shuttle vector harboring Tn551 | 15 |

| pDG1515 | Tetracycline resistance antibiotic cassette in Bluescript KS(+) (Ampr) | [14] |

| pLES205 | pAZ106 containing a 1. 4 kb sigS fragment | 7 |

| pHKM4 | pSC-A containing the sigS-lacZ fragment from pLES205 | This study |

| pHKM5 | pSC-A containing a tet cassette and sigS-lacZ fragment from pLES205 | This study |

| Primers1 | ||

| OL281 | ACT GGA TCC CAG TTG CAG ATG CAT CTC TCC | |

| OL388 | GTT GTC TGA ATA AAT CGA TAA GG | |

| OL522 | ATG TCT AGA GAG TAA TGC TAA CAT AGC | |

| OL523 | ATG TCT AGA CCC AAA GTT GAT CCC TTA ACG | |

| OL909 | ATG CTG CAG CAG GAC CCA ACG CTG CCC GAG | |

| OL1039 | [Biotin]CGT GCC TTC AAT TTG ACC ATC ACG | |

| OL1184 | AGC CGA CCT GAG AGG GTG A | |

| OL1185 | TCT GGA CCG TGT CTC AGT TCC | |

| OL1471 | TTT ATG GTA CCA TTT CAT TTT CCT GCT TTT TC | |

| OL1562 | [biotin]GTA ATC CAT TGT TAC CTC CCG | |

| OL1563 | [biotin] GTG GTG TTT GTT GTA TAC GTC | |

| OL1568 | CGA TTA CGC AAA TGA ATG | |

| OL1569 | CAA GTA GTC ATT CTC CAA G | |

| OL1942 | GTA ATC CAT TGT TAC CTC CCG | |

| OL1943 | GTG GTG TTT GTT GTA TAC GTC | |

| OL2967 | [biotin]GGC TTT CAA TTT GAT TAC GTT T | |

| OL2968 | [biotin]CTA AAT TAA AAG TAT AAC TGC ATT G | |

| OL2979 | [biotin]GTA CAC CTC ATA TTA CGA CTT TTT C | |

| OL2980 | [biotin]CAT TAG TGA GAA TCA TTG TCA ATT AG | |

| OL3012 | [biotin]CCA TGA TAA CCC TCA CTT AAT ATA | |

| OL3013 | [biotin]GAC ATA ACC TTC ACC TCG ATA GCA | |

| OL3014 | CCA TGA TAA CCC TCA CTT AAT ATA | |

| OL3015 | GAC ATA ACC TTC ACC TCG ATA GCA | |

| OL3016 | [biotin]GCA TCT GAC ACA CAA GTA TTT GTG TTG | |

| OL3017 | [biotin]CCG AGT CTG TCT TTA ACA CTG | |

| OL3018 | GCA TCT GAC ACA CAA GTA TTT GTG TTG | |

| OL3019 | CCG AGT CTG TCT TTA ACA CTG |

1Restriction sites are italicized.

Construction of a tetracycline marked sigS-lacZ strain

The sigS promoter region and lacZ gene were amplified from a previously constructed reporter fusion strain using primers OL281/OL909 (Table 1) [7]. This fragment was subsequently TA cloned into pSC-A using StrataClone PCR Cloning Kit as described by the manufacturer’s instructions (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). In order to generate a tetracycline marked fusion, primer pair OL522/OL523 was used to amplify the tet resistance cassette from pDG1515 then digested with XbaI and ligated into similarly cut pSC-A containing the sigS-lacZ fragment. The resulting plasmid, pHKM5, was then transformed into S. aureus RN4220 and integrants were confirmed by PCR analysis using a forward primer that is specific to sigS, and a reverse primer that is specific to lacZ. A representative clone was then used to transfer the fusion into S. aureus 8325–4 by φ11-mediated transduction. This produced strain HKM17, which was confirmed by similar PCR analysis.

Identification of proteins that bind to the sigS promoter using a biotin pull down assay

A 553 base pair fragment, which contains the sigS promoter sequence, was amplified by PCR using primers OL388 and OL1039, with the upstream primer containing a biotinylated tag. PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel, and purified using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Overnight cultures of S. aureus RN4220 were subcultured into 100 ml of fresh TSB and grown for 3 hours, before being standardized to an OD600 of 0.05 and allowed to grow for 2 hours. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed in 10 ml of TE buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8), before being resuspended in 1 ml of phosphate buffered saline. Cytoplasmic proteins were then extracted as previously described [15], before being stored at −80°C.

Dynabeads M-280 streptavidin magnetic beads (Life Technologies) were transferred to a 1.5 ml centrifuge tube and placed on a magnetic rack for 2 minutes before being washed twice with 1 ml PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100. Beads were then incubated with either the sigS promoter region, nsaRS promoter region (control DNA fragment) or nuclease free water (negative control) at 25°C for 15 minutes. Following this, beads were again washed twice with 1 ml PBS and 0.2% Triton X-100. In order to prevent promiscuous protein binding to any unbound streptavidin beads, the beads/DNA complex was then incubated in the presence of 10 μg ml−1 biotin for 15 minutes at 25°C, followed by two washes with PBS and Triton X-100. RN4220 protein lysates were thawed on ice before the addition of 2 μg of poly(dI-dC), to act as a DNA competitor. Lysates were then added to the beads/DNA complex and incubated for 30 minutes at 25°C. Samples were subsequently washed 5 times with 1 ml of PBS and 0.2%Triton X-100, before being eluted with 50 μl of nuclease free water. Samples were run on an SDS-PAGE gel and silver-stained to visualize proteins, before being subjected to in-gel trypsin digestion as previously described [16], and identification by mass-spectrometric analysis.

Transposon mutagenesis and DNA sequencing of insertion sites

Transposon mutagenesis was carried out as previously described [17]. Briefly, a plasmid harboring the Tn551 transposon, pRN3208, was introduced into an 8325–4 sigS-lacZ strain by φ11-mediated transduction. The resulting strain, HKM18, was initially grown overnight at 30°C on a TSA plate containing 0.25 mM CdCl2, 5 μg ml−1 erythromycin, 5 μg ml−1 tetracycline (CET). A flask of 100 ml TSBCET was inoculated from this plate and grown overnight at 30°C. A 5 ml volume from the overnight was washed once with TSB and resuspended in 100 ml TSB containing erythromycin, and grown at 43°C. After 4 hours, another 5 ml of culture was transferred to 100 ml TSB containing erythromycin and allowed to grow at 43°C until the OD600 reached 1.5 [18]. One ml aliquots were then collected via centrifugation, resuspended in TSB glycerol (20% v/v) and stored at −80°C for future analysis. The CFU ml−1 and insertion rate of the library was determined via serial dilution and plating on TSA containing erythromycin and TSA containing cadmium chloride (0.25 mM). The CFU ml−1 was determined to be 5.9 × 109 and the insertion rate was 99.4%. For analysis, glycerol stocks were plated onto TSA containing erythromycin and 5-bromo-4-chloro-2-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (X-GAL) at approximately 200 colonies per plate and analyzed for the appearance of blue colonies, indicating sigS upregulation. Isolates with blue coloration were collected, and used to prepare φ11 phage lysates. To confirm linkage of the phenotype with the transposon, mutations were transduced into a clean 8325–4 sigS-lacZ strain and again inspected for blue coloration. Any strain resulting in a positive result during this secondary screen was stored as a glycerol at −80°C, and genomic DNA prepared utilizing a QIAGEN DNeasy Tissue Kit, as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The identification of insertion sites was performed utilizing single-strand DNA sequencing with primer OL1130, specific to Tn551. This approach allows for the sequencing of a small fragment of Tn551, and approximately 500 bp of flanking genomic DNA outside of the transposon. Insertion sites were then identified utilizing NCBI BLAST analysis.

In an effort to identify genes that have a positive impact on sigS expression, the previously generated 8325–4 sigS-lacZ transposon library was also plated on agar that contains 0.25 mM of the DNA damaging agent methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) and X-GAL. MMS was used because previous studies by our lab have shown that expression of sigS is induced by this agent [8]. Glycerol stocks of the transposon library were thawed, and plated at approximately 200 colonies per plate, before being analyzed for clones that lacked a blue coloration. Such colonies were isolated, subject to secondary screening, and the insertion site of transposon insertion determined, as described above.

β-Galactosidase assay

Levels of β-galactosidase activity were measured as described previously [19]. The results presented herein are the average of three independent replicates.

Generation of 8325–4 sigS-lacZ NTML strains

The Nebraska Transposon Mutant Library (NTML) was acquired from the Network on Antimicrobial Resistant in Staphylococcus aureus (NARSA). Those mutations identified in the Tn551 screens leading to altered sigS expression were transduced from relevant NTML clones into the 8325–4 sigS-lacZ strain using φ11. Each mutant was then validated using a gene specific primer (see Additional file 1: Table S1) and a primer specific to the bursa aurealis transposon (OL1471, Table 1).

Nitronitrosoguanidine mutagenesis

An overnight culture of S. aureus SH1000 sigS-lacZ was synchronized and allowed to grow to mid-exponential phase, before 50 μg ml−1 N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) was added, and allowed to incubate at 37°C for 60 min [20]. Cells were then collected via centrifugation at 3,500 rpm, washed, resuspended in TSB and allowed to recover at 37°C for 2 h [21,22]. Following the recovery period, 1 ml aliquots were collected via centrifugation and stored in TSB glycerol at −80°C. The CFU ml−1 for cultures was determined both prior to MNNG exposure, and after, in order to determine survival rates (≥50% required). For analysis, the frozen samples were allowed to thaw, before being serially diluted in sterile PBS and plated on to TSA containing X-GAL. Plates were incubated overnight, before being inspected for the appearance of blue colonies, indicating increased sigS expression as a result of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) caused by the MNNG.

Whole genome sequencing and data analysis

Whole genome sequencing was performed using an Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine (PGM, Life Technologies) according to manufacturer’s protocols, as described by us previously [23]. Genomic DNA was extracted as described above and 1 μg of total DNA was fragmented using The Ion Xpress™ Plus Fragment Library Kit (Life Technologies). DNA was size selected using the E-gel system (Invitrogen) based upon the manufacturer’s recommendations for 200 base pair sequencing protocols. The size selected DNA was used to generate templated Ion Sphere Particles (ISPs) using an Ion OneTouch™ 200 Template Kit and an Ion OneTouch instrument. The resulting ISPs were sequenced on an IonTorrent 318 chip using a PGM™ 200 Sequencing Kit (Life Technologies). Sequences generated were exported in the .sff file format and analyzed using the CLC Genomics WorkBench software package. The previously sequenced genome of closely related strain NCTC 8325 was downloaded from the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/154?project_id=57795) and used as a reference to assemble each of the sequenced strains. Variant calling was performed within CLC Genomics WorkBench, and polymorphisms were selected on the basis that they were present in >95% of reads, with a minimum coverage of at least 10 reads.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed as previously described using primers specific to sigS [8,24]. The 16S rRNA gene was used as a control, as previously described [25].

Purification of recombinant DNA binding proteins

The coding regions of lacR, cymR, and kdpE were cloned into pET24d + as previously described [7,26], before being transferred to E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS. Cloning the coding region of the specified genes into pET24d + results in the addition of a C-terminal histidine tag. Expression of lacR, cymR and kdpE was induced with the addition of 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG) to a growing 2 liter culture (OD600 = 0.6), before being allowed to grow for 5 hours at 37°C. Cells were harvested, resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) containing 1 mg ml−1 lysozyme, and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour, followed by sonication. All crude protein extracts were then applied to a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) metal- affinity matrix followed by washing with wash buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). Proteins were eluted using elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). Following elution, purified proteins were dialyzed for 48 hours against a dialysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, pH 8.0). The resulting C-terminally histidine tagged, purified proteins were stored in dialysis buffer supplemented with 10% glycerol and kept at −20°C.

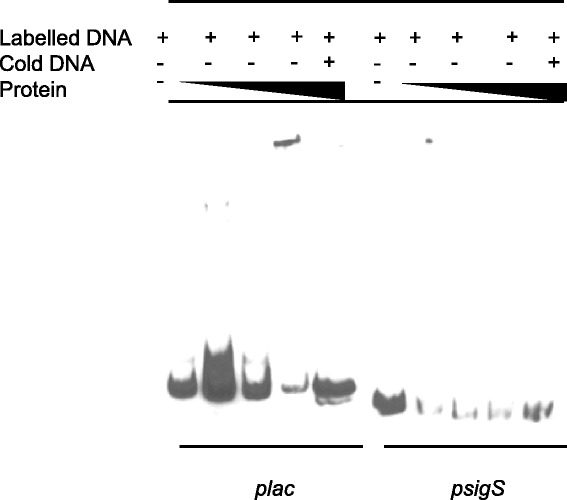

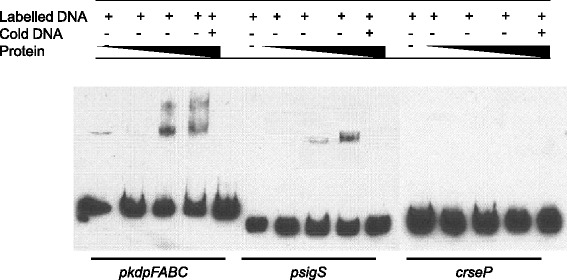

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

The promoter of sigS was amplifying using primers OL1562 and OL1563 and chromosomal DNA isolated from S. aureus USA300 HOU. As a positive control for purified LacR, the promoter fragment of the lac operon was amplified using primers OL2967 and OL2968. It has previously been shown that LacR binds to and represses transcription of the lac operon [27]. For CymR, the promoter of mccAB was amplified using primers OL3016 and OL3017. CymR has previously been shown to directly bind and repress transcription of this operon [28]. The positive control for the response regulator KdpE was the promoter region of kdpFABC, which was amplified using OL3012 and 3013. KdpE has previously been shown to bind and repress transcription from kdpFABC [29]. The PCR products were biotinylated at the 5’ and 3’ ends, and shift assays were performed using LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Pierce) according to the manufactures protocol. Briefly, labelled promoter fragments were incubated at 25°C for 20 minutes with various amounts of purified proteins in 20 μl reaction buffer (1× binding buffer, 2.5% glycerol, 50 ng ml−1 poly dI-dC, and 0.05% NP-40). The binding buffer used for LacR contained 20% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM DTT, 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, and 0.25 mg/ml poly dI-dC. The CymR and KdpE binding buffer contained 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 10% glycerol.

Results

The identification of proteins that modulate sigS expression

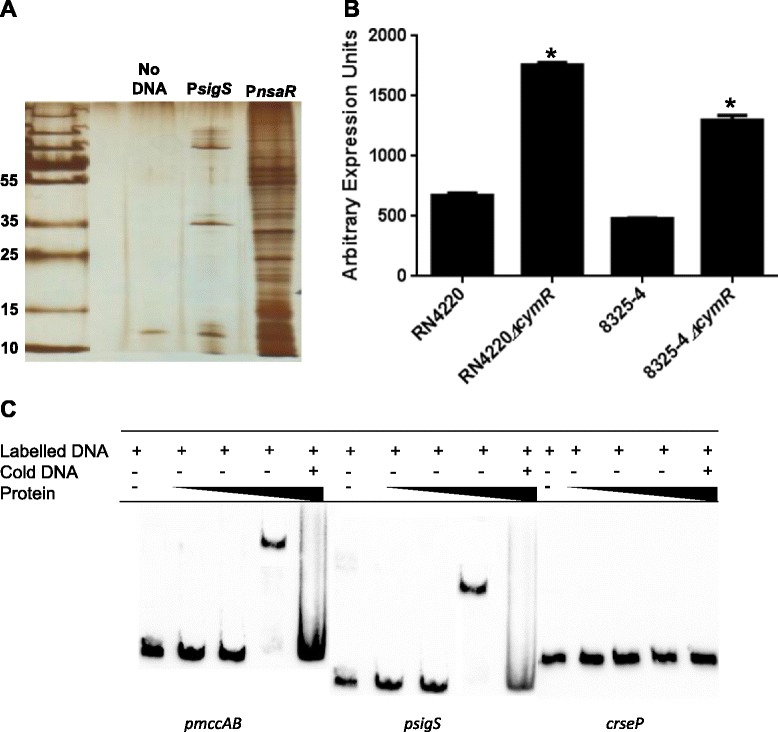

Previous studies on sigS expression by our group have demonstrated significant variability across different wild-type strains. This has led us to hypothesize in the past that there may be regulatory circuits that exists in S. aureus to control the expression of this gene [8]. As such, in order to identify direct regulators of sigS expression, a pull down assay was performed using a biotinylated sigS promoter fragment immobilized on streptavidin magnetic beads. Protein lysates from strain RN4220 were utilized in these assays, as our group previously demonstrated sigS expression to be highest in this background under standard conditions [8]. Protein lysates from RN4220 grown under standard conditions for 2 h were incubated with the biotinylated sigS promoter fragment. This time point was selected in order to identify modulators of sigS that effect transcript levels as the bacteria transition from minimal sigS expression (2 h) to maximal expression by hour 3 [8]. Proteins that were bound to the promoter region were harvested, and separated by SDS PAGE analysis followed by silver staining (Figure 1A). We observed that while there were no proteins detected in our no DNA control lane, several distinct bands were detected in the sigS test lanes. For our control promoter (nsaXRS), we observed a number of proteins bound to this fragment, which likely results from the fact that this locus is very highly expressed, and subject to complex, multifactorial regulation [30,31]. The identity of proteins bound to the sigS promoter was then determined using mass-spectrometric analysis, identifying 21 different factors (Additional file 1: Table S2). Whilst a number of proteins were identified with known or predicted DNA-binding roles (including DNA replication and transcription, stress proteins and exonucleases), only one was a known transcriptional regulator: the cysteine biosynthesis pathway transcriptional regulator, CymR. As this did not appear in either of the control samples, we next set out to determine if CymR had a measurable impact on sigS expression using qPCR and mutant strains deficient in the cymR gene. This analysis was performed in strains RN4220 and 8325–4: the former because this is the background where the identification was made and the latter as we have previously shown that this strain is highly sensitive to sigS modulation [8]. For RN4220 and 8325–4, RNA was harvested at 3 and 5 hours, respectively, as this is the time for each strain when sigS is maximally expressed [8]. Upon analysis, we observed a 2.7- and 2.6-fold increase, respectively, in sigS expression in the 8325–4 and RN4220 cymR mutants compared with the wild-type strains (Figure 1B). This would seem to indicate that the CymR protein plays a role in the negative regulation of sigS expression in S. aureus. To determine if this effect is indeed direct, we sought to recapitulate the binding of this protein to the sigS promoter in vitro using electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) (Figure 1C). The promoter region of mccAB was used as a positive control because Soutourina et al. have previously shown that CymR directly binds to this region [28]. When the mccAB promoter fragment was incubated with increasing amounts of CymR, a clear shift is observed at higher concentrations of protein. Interestingly, parallel experiments with the sigS promoter fragment revealed similar shifts, which would indicate that CymR is a direct regulator of sigS expression. In order to demonstrate that this effect was specific and not a result of promiscuity, we performed EMSAs using a biotinylated DNA fragment that was amplified from the coding region of the gene rseP. In these studies we did not observe any shift of the DNA, validating that the binding observed for sigS is indeed specific, and that CymR directly regulates, and represses, transcription from the sigS promoter.

Figure 1.

CymR is a direct repressor of transcription from the sigS promoter. (A) A pull down assay was performed using crude protein lysates harvested from RN4220 at hour 2 and a biotinylated sigS promoter DNA probe. The identity of protein bands was determined by LC/MS analysis. (B) qPCR analysis of sigS expression in a cymR mutant compared to its respective parental strain, in the 8325–4 and RN4220 backgrounds. Error bars are shown as ± SEM, * = p <0.05 using a Student’s t-test. (C) An electrophoretic mobility shift assay was performed using purified CymR, and the promoter region of mccAB (positive control), the promoter region of sigS (test), and an intergenic region from the rseP gene (rseP; negative control). CymR was added at increasing concentrations of 0.01, 0.1 and 1 μM in all panels.

A global screen to identify genes that negatively regulate sigS expression

To assess whether additional regulators of sigS expression exist in S. aureus beyond CymR, we next used a global genetic approach to identify modulating factors. Therefore, we employed transposon mutagenesis screen in conjunction with an 8325–4 sigS-lacZ reporter fusion strain. This background was chosen because our previous works have shown that 8325–4 is the most sensitive wild-type strain to sigS modulation, and that information gained using this strain is conserved amongst other S. aureus wild-types [8]. As such, we screened >10,000 clones from our transposon library, and identified 123 that had increased sigS expression. A secondary screen was performed on these mutations, by transducing them into a clean 8325–4 sigS-lacZ fusion background. This was to ensure that the increase in expression is due to direct gene disruption by Tn551, rather than the result of SNPs that may have accumulated during construction of our library. We determined that 96 mutants from our secondary screen recapitulated the increase in sigS expression on media containing X-GAL. Upon sequence analysis, we identified 58 unique insertion sites, with 49 found to be in coding regions, and a further 9 found to be intergenic between open reading frames (Additional file 1: Table S3).

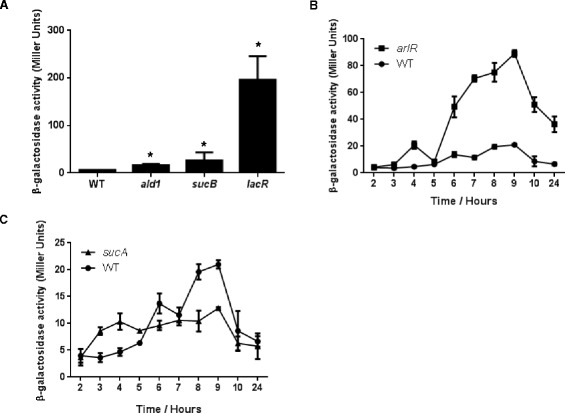

Analysis of transposon insertion sites revealed many were clustered in one particular region of the genome (SACOL1411 to SACOL1490). We have previously identified this region as a hot-spot for Tn551 insertion [17], and therefore sought to validate our findings further to ensure they specifically related to sigS expression. To achieve this, we made use of the Nebraska Transposon Mutant Library (NTML), a collection of bursa aurealis transposon mutants in almost all non-essential S. aureus gene [32]. Of the 49 identified insertions from our screen that were in coding regions, 40 had NTML mutants available (Additional file 1: Table S3). Therefore, each of the NTML insertions for these 40 genes were separately introduced into our 8325–4 reporter strain. In order to determine if the NTML mutants recapitulated our sigS expression findings from the Tn551 screen, all mutants were first analyzed using a plate based assay. Upon analysis, 20 of the transduced NTML mutants were blue when plated on media containing X-GAL (Table 2), whilst the remaining 20 did not reproduce the findings of their counterpart Tn551 insertions. β-galactosidase assays were then performed on the NTML mutants that tested positive, to specifically quantify changes in sigS expression. As such, NTML reporter fusion strains were grown for 5 h in TSB, as we have previously shown this to be the window of peak sigS expression in strain 8325–4 [8]. Interestingly, only three mutants were found to have increased sigS expression at this time point (Figure 2A): insertions in ald1 (an alanine dehydrogenase, 2.6-fold), lacR (the lactose phosphotransferase system repressor, 31-fold) and sucB (dihydroipoamide succinyltransferase, 4.2-fold). For the 17 mutants that did not demonstrate increased sigS expression at this time point, we next performed transcriptional profiling every hour over a 10 hour time course. In doing so, we observed increased sigS expression for an additional 2 mutants (Figure 2B and C): insertions in arlR (a DNA-binding response regulator), and sucA (2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase E1 component). For arlR we observed an increase in sigS expression at all hours assayed (maximal change =6.1 –fold at 9 h) except at 5 h; whilst for sucA, a gene transcribed upstream of sucB, we observed a 2.2 fold increase at hour 4. With regards to the remaining 15 transposon mutants, we did not see an increase in sigS expression over the 10 hour time course. However, we did observe a blue coloration when plated on media containing X-GAL, which does not occur with wild-type 8325–4 sigS-lacZ fusions. As such, the increase in sigS expression observed for these strains either takes place deeper into stationary phase than assessed herein; or as a result of growth on a solid surface compared with liquid culture.

Table 2.

Transposon insertions resulting in increased expression of sigS

| Accession number | NE number a | Tn 551 insertion site | Gene | Hits b | Unique c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA metabolism: DNA replication, recombination and repair | |||||

| SACOL0566 | NE544 | Nucleoside permease | nupC | 1 | 1 |

| Regulators | |||||

| SACOL0513 | NE1883 | Transcriptional regulatory protein | glcT | 1 | 1 |

| SACOL1451 | NE1684 | Response regulator | arlR | 1 | 1 |

| SACOL1436 | NE9 | Modulator of SarA | msa | 1 | 1 |

| SACOL2086 | NE1218 | Transcriptional regulator, TenA family | tenA | 1 | 1 |

| SACOL2188 | NE436 | Lactose phosphotransferase system repressor | lacR | 5 | 1 |

| Cell envelope associated | |||||

| SACOL1472 | NE1 | Cell wall associated fibronectin-binding protein | ebh | 6 | 2 |

| Transporters | |||||

| SACOL0684 | NE1292 | Na+/H + antiporter, MnhE component, putative | 2 | 1 | |

| SACOL1319 | NE1580 | Glycerol uptake facilitator protein | 5 | 1 | |

| SACOL1392 | NE142 | Sodium:alanine symporter family protein | 3 | 1 | |

| SACOL1414 | NE1609 | Peptide ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | 4 | 1 | |

| Amino acid biosynthesis | |||||

| SACOL0168 | NE595 | Glutamate N-acetyltransferase/amino-acid acetyltransferase | argJ | 2 | 1 |

| SACOL1349 | NE809 | Threonine aldolase | 1 | 1 | |

| SACOL1448 | NE1391 | Dihydroipoamide succinyltransferase | sucB | 1 | 1 |

| SACOL1449 | NE547 | 2-Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, E1 component | sucA | 3 | 1 |

| SACOL1478 | NE1136 | Alanine dehydrogenase | 1 | 1 | |

| SACOL2045 | NE1177 | Ketol-acid reductoisomerase | 1 | 1 | |

| Protein synthesis and modification | |||||

| SACOL1369 | NE1904 | 50S ribosomal protein l33 | 4 | 1 | |

| SACOL1480 | NE582 | Hypothetical protein (ribosome associated GTPase domain) | 1 | 1 | |

| Unknown function | |||||

| SACOL1452 | NE577 | PAP2 family protein | 1 | 1 | |

aNE numbers are the identification number in the Nebraska Transposon Mutant Library.

bHits refer to the total number of Tn551 insertion sites identified for a particular gene.

cThe unique number of insertions sites refers to those insertions that are a result of distinctive insertion events.

Figure 2.

Transcriptional profiling of sigS in transposon mutants found to negatively effect expression. (A, B, and C) Mutant strains bearing a sigS-lacZ fusion were grown in TSB at 37°C and samples withdrawn at the times specified. β-Galactosidase activity was measured using 4-MUG as a substrate to determine sigS expression levels. Assays were performed on duplicate samples and the values averaged. The results presented are from three independent experiments. Error bars are shown as ± SEM. Significance was determined by a Student t test; *indicates a p value of <0.05.

Transposon mutagenesis to identify positive activators of sigS expression

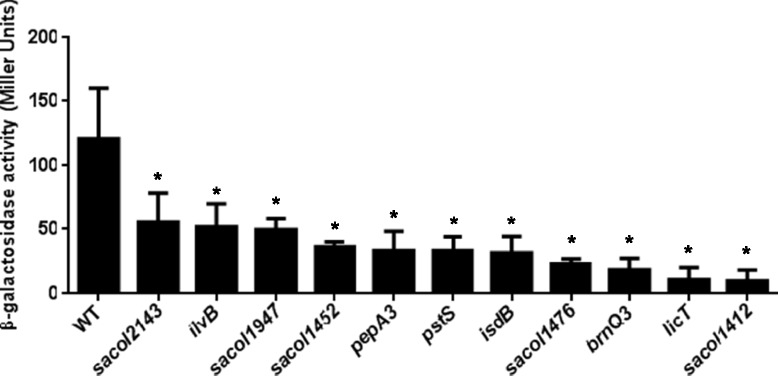

The advantage of using the 8325–4 sigS-lacZ fusion for transposon mutagenesis is that it can be performed in reverse, meaning that we can use a chemical that induces expression of sigS alongside X-GAL, and identify positive regulators by a lack of blue coloration upon transposon insertion. As such, media was prepared using 0.25 mM MMS and X-GAL, and our Tn551 mutant library was again subject to screening. In total, we assessed >10,000 clones and identified 349 that had no observable sigS expression, determined by a lack of blue coloration of colonies. A secondary screen was performed with these strains, yielding 86 that recapitulated the phenotype. This relatively low number of clones that retained phenotype, compared to our original screen, is most likely due to point mutations caused through the use of the DNA damaging agent MMS. Upon sequencing, we identified 35 unique insertion sites (Additional file 1: Table S4), 24 of which occurred within genes, and 11 that were found to be intergenic. Interestingly, 12 insertions occurred within the known hotspot region, whilst a further 5 were identified in both screens (one of which failed to validate in our previous screen, and the other four failed to validate in this screen, see below). In an effort to define which of these elements legitimately influence sigS expression in a positive manner, we again made use of the NTML collection. Of the 24 insertions within ORFs, 21 mutants were available in the Nebraska Transposon Mutant Library. As such, each of these mutations was again transduced into a clean 8325–4 sigS-lacZ strain, and their effects on sigS expression validated by plating on media containing 0.25 mM MMS and X-GAL. Of the 21 mutations assayed, 10 of them were blue when plated on media containing MMS and X-GAL (Table 3), including the remaining 4 that were identified in both screens (thus excluding them from further study). The remaining 11 mutants had abrogated sigS expression, as expect, and were thus subject to transcription profiling in liquid culture in the presence of 0.25 mM MMS for validation (Figure 3). This time, all mutants tested resulted in decreased sigS expression after 5 h of growth, ranging from 2.2-fold (SACOL2143) to 12.2-fold (SACOL1412). Of the elements identified in this screen to positively influence sigS expression, there were insertions in genes whose products are involved in regulation, transport, protein synthesis and modification, amino acid biosynthesis, and cell envelope biosynthesis.

Table 3.

Transposon insertions resulting in decreased expression of sigS

| Accession number | NE number a | Tn551 insertion site | Gene | Hits b | Unique c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulators | |||||

| SACOL1393 | NE1415 | Transcriptional antiterminator, licT putative | licT | 3 | 1 |

| Cell envelope associated | |||||

| SACOL1138 | NE1102 | LPXTG cell wall surface anchor protein | isdB | 1 | 1 |

| Transporters | |||||

| SACOL1424 | NE1459 | Phosphate ABC transporter, phosphate binding protein | 2 | 1 | |

| SACOL1443 | NE44 | Branched chain amino acid transport system II carrier protein | brnQ3 | 7 | 1 |

| SACOL1476 | NE211 | Amino acid permease | 1 | 1 | |

| Amino acid biosynthesis | |||||

| SACOL2043 | NE1166 | Acetolactate synthase, large subunit | ilvB | 1 | 1 |

| SACOL2154 | NE134 | Arginase | rocF | 1 | 1 |

| Protein synthesis and modification | |||||

| SACOL1402 | NE1306 | Glutamyl aminopeptidase, putative | pepA3 | 1 | 1 |

| Unknown Function | |||||

| SACOL1452 | NE577 | PAP2 family protein | 1 | 1 | |

| Hypothetical proteins | |||||

| SACOL1947 | NE1706 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 3 | 1 | |

| SACOL2143 | NE1104 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2 | 1 | |

aNE numbers are the identification number in the Nebraska Transposon Mutant Library.

bHits refer to the total number of Tn551 insertion sites identified for a particular gene.

cThe unique number of insertions sites refers to those insertions that are a result of distinctive insertion events.

Figure 3.

Identification of positive regulators of sigS expression. Mutant strains bearing a sigS-lacZ fusion were grown in TSB at 37°C and sampled after 5 h of growth. β-Galactosidase activity was measured using 4-MUG as a substrate to determine sigS expression levels. Assays were performed on duplicate samples and the values averaged. The results presented are from three independent experiments. Error bars are shown as ± SEM. Significance was determined using a Student t test; *indicates a p value of <0.05.

Inducing sigS expression in strain SH1000

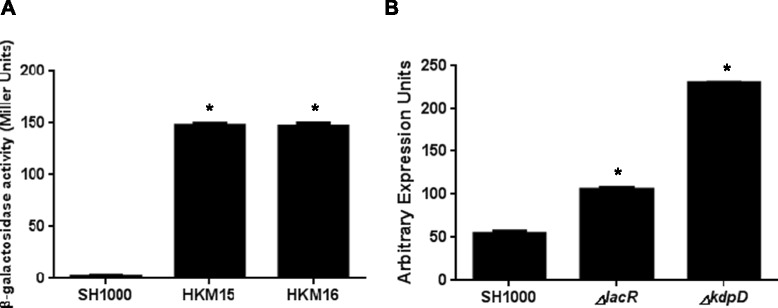

S. aureus strain SH1000 is identical to 8325–4, apart from an 11 bp deletion in the σB controlling phosphatase, rsbU. Despite this similarity, SH1000 does not demonstrate detectable sigS expression during regular growth; an effect that appears to be more complex than mere σB mediated control [7,8]. Therefore, to explore whether sigS upregulation could be achieved in this strain, we next exposed our SH1000 sigS-lacZ fusion strain to the DNA mutagen, methyl nitro-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG). MNNG acts by adding alkyl groups to O6 of guanine and O4 of thymidine, which can lead to transition mutations. This has an advantage over transposon mediated technologies as it can assess both loss- and gain-of function, rather than only the former. Upon analysis, we identified 76 strains that had an increase in expression of sigS as determine by blue coloration when plated on media containing X-GAL. To quantitate the increased sigS expression observed on a plate, we selected two strains, HKM15 and HKM16, and subjected them to continuous growth analysis in liquid media (Figure 4A). We determined that both HKM15 and HKM16 resulted in a 75-fold increases in sigS expression after 5 h of growth, compared to the wild-type. To identify the specific mutations that result in these outcomes, we next subjected these two strains to whole genome sequencing, alongside the SH1000 parent, with resulting data analyzed using the CLC Genomic Workbench software. When one compares these two datasets, we found 9 mutations that were common to both strains (Table 4). Importantly, within this list are two known transcriptional regulators, LacR, which we have already identified in this study as influencing sigS expression, and KdpD, a membrane sensor histidine kinase. In order to evaluate the effect these mutations have on sigS expression, the relevant NTML mutations were transduced into SH1000, and qPCR profiling was performed (Figure 4B). We observed a 2.0-fold increase in sigS expression in the SH1000 lacR mutant, while we observed a 4.0-fold increase in sigS expression in SH1000 kdpD. This would indicate that lack of lacR and kdpD also have a role in regulating sigS expression.

Figure 4.

Nitrosoguanidine mutagenesis identifies additional regulators of sigS expression. (A) The SH1000 sigS-lacZ fusion strain was subjected to MNNG mutagenesis. Two resulting clones were selected for further analysis during growth in TSB at 37°C. HKM15 and HKM16 were grown along side the parent strain, SH1000, with samples collected at 5 hours. β-Galactosidase activity was measured using 4-MUG as a substrate to determine sigS expression levels. Assays were performed on duplicate samples and the values averaged. The results presented are from three independent experiments. Error bars are shown as ± SEM. (B) qPCR for sigS expression was performed on SH1000 strains containing a mutation in either lacR or kdpD. Error bars are shown as ± SEM. Significance was determined using a Student t test; *indicates a p value of <0.05.

Table 4.

SNPs common to both SH1000 sigS-lacZ NTG generated mutants HKM15 and HKM16

| Annotation | Amino acid change | Function | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HKM15 | HKM16 | ||

| SACOL0400 | V342I | P307L | Transport SgaT, putative |

| SACOL1103 | G64A | G64A | Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex E1 component |

| SACOL1213 | E290K | A319V | Dihydroorotase |

| SACOL1472 | A3615T | G2291D | Cell wall associated fibronectin-binding protein |

| SACOL1686 | D388N | D388N | Histidyl-tRNA synthetase |

| SACOL2070 | P257S | P257S | Sensor histidine kinase KdpD |

| SACOL2150 | A1128T | V1818I | SasB protein (fmtB) |

| SACOL2176 | A382V | A382V | Osmoprotectant transporter, BCCT family |

| SACOL2188 | G8E | G112E | Lactose phosphotransferase system repressor |

In an effort to determine if the effect on sigS expression is direct or indirect we performed EMSAs using purified LacR and KdpE. KdpE was used because it is the partner response regulator, phosphorylated by KdpD. With regards to LacR, the promoter region of the lac operon was used as positive control, as it has previously shown that LacR directly binds to this region [27]. As such, we incubated the lac promoter fragment with increasing amounts of LacR, and, as expected, observed a shift for the lac promoter fragment at higher protein concentrations (Figure 5). However, when the sigS promoter fragment was used, no such shift was observed. This suggests that, despite LacR clearly influencing sigS expression (it was identified in two of our screens), these effects appear to be indirect.

Figure 5.

LacR does not directly regulate sigS expression. Electrophoretic mobility shift mobility assays were performed using purified LacR, the lac promoter region (positive control), and the promoter region of sigS (test). LacR was added at increasing concentrations of 0.01, 0.1 and 1 μM in all panels.

With regards to KdpE, we first used the promoter region of kdpFABC as a positive control, because it has previously been shown that KdpE directly binds this region [29]. As such, we incubated the kdpFABC promoter fragment with increasing amounts of KdpE, and detected a shift for this fragment at higher protein concentrations (Figure 6). Importantly, we also detected a shift for the sigS promoter fragment at similar concentrations, which would indicate that KdpE is a direct regulator of sigS expression. To determine if this is specific effect, and not the result of promiscuous binding by KdpE, we again used our internal fragment from the coding region of rseP as a negative control. In these studies we did not observe any shift of the DNA, validating that the binding observed for sigS is indeed specific, and that KdpDE directly regulates, and represses, transcription from the sigS promoter.

Figure 6.

KdpE directly regulates sigS expression. Electrophoretic mobility shift mobility assays were performed using purified KdpE, the promoter region of kdpFABC (positive control), the promoter region of sigS (test), and an intergenic region from the rseP gene (negative control). KdpE was added at increasing concentrations of 0.1, 0.5 and 0.75 μM in all panels.

Discussion

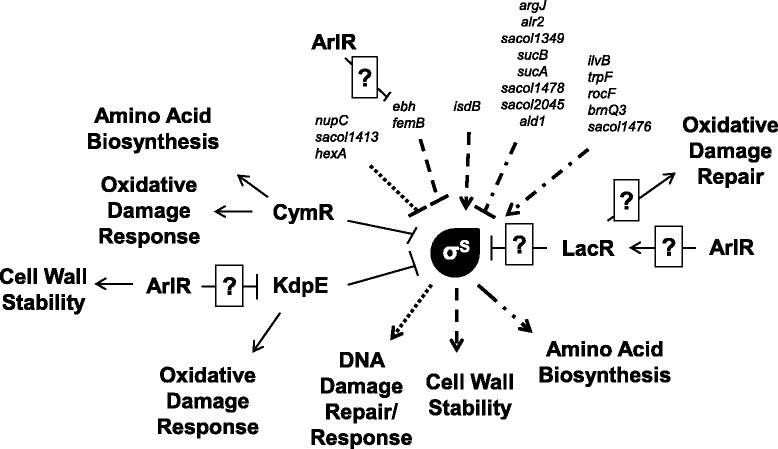

The average bacterial genome is estimated to encode at least six ECF sigma factors [5,33]. S. aureus is a highly successful pathogen with complex regulatory circuits that, interestingly, encodes only one ECF sigma factor, σS. This sigma factor has previously been shown to be important in the stress and virulence response of S. aureus [7]. In addition, we have also shown that sigS is differentially regulated across a number of S. aureus wild-type strains, which would indicate a network of regulation may exist, controlling the expression of this element. In earlier work by our group we have investigated the regulation of sigS by environmental signals in response to external stress; therefore in this study, we investigated the genetic mechanisms that regulate this transcription factor. We observed a number of findings that appear to correlate with our previous works regarding the function of σS, detailed as follows (and in Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of sigS regulation and role within the S. aureus cell. Shown are genes identified in this study that either positively or negatively regulate sigS transcription; alongside known roles for σS from our previously published works. A correlation of input factors, to output functions, is denoted by similar line dashing.

To explore direct regulators of sigS expression, we used a biotin pull down assay in conjunction with the sigS promoter, and identified CymR as specifically binding to this region of DNA. Using qPCR we were able to demonstrate that sigS expression actually increased in a cymR mutant, indicating that this regulator is acting as a repressor. CymR belongs to the poorly characterized Rrf2 family of proteins, and has been shown to be the master regulator of cysteine metabolism in S. aureus [28,34]. Functionally, CymR binds directly to the promoter sequences of eight transcription units corresponding to 18 genes, and represses the transcription of elements involved in pathways leading to cysteine formation. Interestingly, in the presence of reactive oxygen species (ROS), it has been shown that there is derepression of several direct CymR targets [8,28,34]. We ourselves have previously shown that sigS expression is inducible during oxidative stress, and that sigS mutants are more sensitive to ROS. This would therefore suggest a link between cysteine metabolism, CymR, oxidative stress and sigS expression in S. aureus.

We identified further repressors of sigS expression in S. aureus using transposon mutagenesis as well as an MNNG based mutagenesis screen, with the most profound effects observed resulting from the inactivation of LacR. In S. aureus, the lacR gene encodes the transcriptional regulator for the lactose utilization system [27]. Because this gene encodes a transcriptional regulator, we were interested to see if the protein binds to the promoter region of sigS. Using EMSAs we determined that the regulatory affect we observe for sigS by LacR is indirect. It is unclear why the S. aureus LacR protein may function to regulate genes other than those involved in lactose utilization; however, it does share homology with deoR of E. coli, which is involved in repressing genes that are a part of the catabolism of deoxyribonucleosides. Interestingly, preliminary work by our group suggests that sigS may be involved in the de novo assembly of nucleotides (Miller and Shaw, unpublished observation). As such, it is possible that LacR may have retained an evolutionary role in nucleoside catabolism, which explains why it might connect to sigS expression in S. aureus. In addition, we also observed that when the response regulator arlR is disrupted there is an increase in sigS expression. This response regulator is involved in autolysis, adhesion and virulence of S. aureus. Interestingly, arlR mutants display an increase lysis when exposed to Triton X-100, which is a phenotype that we have previously described for sigS mutants [7,35]. Interestingly, an array performed on an arlR mutant indicates that this response regulator directly and/or indirectly controls expression of at least 114 genes. These include several genes identified in this study, such the lacABCDFEG operon, which is negatively regulated by lacR; ebhAB, which encodes an adhesin identified in our transposon screen, and the two component system kdpDE. In the context of this latter element we identified mutations in the sensor histidine kinase, kdpD as negatively influencing sigS expression. This gene is part of the two component system, KdpDE, which is involved in sensing and responding to potassium levels in the cell [36]. There has been an increase in evidence that demonstrates KdpDE is an adaptive regulator involved in the virulence and intracellular survival of pathogenic bacteria. Specifically, KdpDE has been shown to regulate genes involved in responding to oxidative stress, which we have previously shown sigS to be involved in [37].

We also identified a number of other genes as negatively influencing sigS expression that would appear to corroborate previous studies performed by our group. For example, we have shown that sigS expression is increased in the presence of DNA damaging agents [8]. Herein we identified insertions in genes that are involved in DNA replication, recombination and repair pathways as influencing the expression of sigS. Specifically, we identified a mutation in SACOL1413, which is a putative helicase demonstrating homology to Snf2 family of proteins that are thought to function in DNA damage repair [38]. Again, connected with this, we have demonstrated that cells deficient in sigS are more sensitive to a variety of DNA damaging agents, and that expression of sigS is similarly increased in the presence of such stressors. A mutation in the DNA mismatch repair protein, hexA, was also identified in our screen. HexA is a major component of the methyl mismatch repair system [39]. In S. aureus, disruption of hexA leads to a higher frequency of strains acquiring random SNPs [39]. Thus, it is plausible that, in the absence of hexA, the increased level of natural mutation would instigate a DNA-damage like-response, which seems to involve σS in the S. aureus cell. In addition, disruption of nupC, which encodes a nucleoside permease, increases expression of sigS. In the closely related bacteria B. subtilis, NupC is responsible for transporting all nucleosides other than hypoxanthine and guanine, which are then catabolized to purine and pyrimidine bases, and returned to the nucleotide pool for DNA biosynthesis [40]. This is of significant interest, as preliminary work by our group indicates that sigS mutants have severely diminished expression of nucleotide biosynthesis genes (Miller and Shaw, unpublished observation). This would suggest that in the absence of nupC, sigS expression is upregulated to aid nucleotide biosynthesis to replace those not being transported into the cell.

We also identified insertions in two genes that are involved in cell wall biosynthesis as having negative influence on sigS expression. This is of interest as we have previously reported that sigS expression is induced in the presence of antibiotics that targeting the cell wall, and that sigS mutants are more sensitive to this kind of stress [8]. The first of these two elements is ebh, a cell wall associated fibronectin-binding protein. Interestingly, cells deficient in ebh have been found to be more susceptible to lysis by Triton X-100, a phenotype that we also observed with a sigS mutant [8,41]. Ebh, which is localized over the entire cell surface, is the largest protein in S. aureus, and deletion of this factor from the cell has serious consequences to cell wall stability [41,42]. Thus, it is conceivable that in the absence of ebh, the expression of sigS would be increased in an effort to combat cell wall instability. Further to this, inactivation of femB also resulted in an increase in sigS expression. FemB is involved in cell wall biosynthesis, and femB mutants of S. aureus have been shown to have reduced glycine content of their peptidoglycan, leading to decreased cell wall stability and an increase in sensitivity to cell wall targeting antibiotics, such as β-lactams [43]. This data very closely mirrors our previous reports with σS, explaining why cells deficient in femB might upregulate sigS.

There were also six insertions identified in the repressor screen for genes involved in amino acid biosynthesis. These include disruptions in the amino acid metabolism genes asd (aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase), ald1 (alanine dehydrogrenase), alr2 (alanine racemase) and argJ (glutamate N-acetyltransferase). Connected to this, we have previously shown that sigS expression is increased in the presence of amino acid limiting media [8]. Moreover, in an earlier study, we have also demonstrated the importance for a functional σS during extended starvation [7]. As such, it appears possible that disruption in the normal flow of amino acids in the S. aureus cells necessitates that activity of σS. We have also identified insertions in genes involved in alanine biosynthesis, including, SACOL1434. Further to this, in B. subtilis, alr2 is responsible for the interconversion of L-isomer and D-isomer of alanine [44,45]. Interestingly, the ability for bacteria to synthesize D-alanine is essential for the biosynthesis of the cell wall in B. subtilis [45]. Therefore, the disruption of alr2 could lead to an increase in sigS expression via two mechanisms: amino acid limitation and cell wall instability.

In the positive transposon screen, we again identified a number of mutations in genes that are involved in amino acid biosynthesis. These include ilvB (the large subunit of acetolactate synthase), trpF (phophoribosylanthranilate isomerase), brnQ3 (a branch-chain amino acid transporter), and SACOL1476 (a putative amino acid permease) that lead to a decrease in sigS expression. Thus, akin to that suggested above, it is plausible that without the ability to import and/or synthesize amino acids, S. aureus is unable upregulate sigS expression and repair the DNA damage caused by MMS. We also identified a mutation in pepA3, which encodes a putative glutamyl aminopeptidase. Glutamyl aminopeptidases are involved in cleaving glutamic and aspartic amino acids from the N-terminus of proteins. The pepA gene of E. coli encodes aminopeptidase A, a homohexameric multifunctional protein with aminopeptidase and DNA-binding activities, the latter being associated with mechanisms of transcriptional control and DNA recombination. Research has demonstrated that PepA is involved in the transcriptional regulation of the carAB operon, which encodes carbamoylphosphate synthetase; this enzyme catalyzes the ATP-dependent synthesis of carbamoyl phosphate from glutamine [46]. This process is the first committed step in pyrimidine and arginine biosynthesis. As we observed a decrease in sigS expression in a pepA3 mutant, it may suggest a link between amino acid and pyrimidine biosynthesis, and sigS. Interestingly, we have also observed that sigS may be involved in both amino acid biosynthesis and pyrimidine biosynthesis ([8], Miller and Shaw unpublished observations).

In a global effort to identify regulators of sigS expression, two Tn551 transposon screens were performed. A consideration with such approaches is that we have previously shown that Tn551 has particular preference for a 108 kb hotspot region of the genome that extends from SACOL1411 to SACOL1490 [17]. In order to ensure that the findings generated in our study were specifically connected to transposon disruption, and not an artifact of transposition, we first set out to validate the role of genes identified in modulation of sigS expression. In our repressor transposon screen, we identified 51 unique insertion sites, 57% (29 mutants) of which fall within the known Tn551 hotspot. In order to ensure that the sigS repression observed in these mutants directly connected to transposon insertion, we validated all Tn551 insertions possible by parallel creation of mutants using the Nebraska Transposon Library. This is a collection of bursa aurealis transposon mutants in almost all non-essential S. aureus gene [32]. Of the 40 mutants available in the NTML for the repressor screen, only 20 retained phenotype when recreated using the bursa aurealis mutants, with only 9 of 17 from the hotspot region. In our transposon screen for activators of sigS expression, we identified 35 unique insertion sites, 51% (18 mutants) of which fell within the Tn551 hotspot. The NTML contained 21 mutants to test for recapitulation, with 11 proving to retain phenotype upon recreating mutations. In this regard 11 of these mutants were originally in the hotspot, with 8 bursa aurealis transposon mutants validating alteration in sigS expression. Interestingly, we also identified 5 transposon mutants that were common to both screens. However, upon validation, none of the mutants retained phenotypes as both repressors and activators; with one of them proving to have only negative effects on sigS expression, whilst the remaining four were positive effectors. Overall, these findings suggest caution should be applied to performing transposon mutagenesis screens without significant efforts exerted to validate findings. It also suggests that, despite the presence of a Tn551 hotspot in the S. aureus genome, mutations identified within are no more, or less, likely to be artifacts for the phenotypes assessed.

Conclusions

Herein, we present evidence that sigS expression is controlled by a number of factors within the S. aureus cell that are involved in amino acid biosynthesis, DNA-damage repair and cell wall structural integrity. In addition, we have identified a number of transcriptional regulators that influence sigS expression, at least two of which (CymR and KdpE) do so by direct binding to the promoter of this gene. The findings of the present study correlate with our previous works on σS, which show a role for this regulator in the DNA-damage response, and in the resistance to cell wall targeting antibiotics and amino acid starvation [7,8]. Taken together, these results confirm our contention that sigS expression is tightly regulated within the S. aureus cell in a complex and multifactorial manner. A continued exploration of the role of this enigmatic protein remains a primary focus of our laboratory’s research endeavors.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by grant AI080626 (LNS) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease.

Abbreviations

- X-GAL

5-bromo-4-chloro-2-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside

- EMSA

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- ECF

Extracytoplasmic function

- h

Hour

- ISPs

Ion Sphere Particles

- IPTG

Isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside

- LB

Luria-Bertani

- MMS

Methyl methanesulfonate

- NTML

Nebraska Transposon Mutant Library

- NARSA

Network on Antimicrobial Resistant in Staphylococcus aureus

- Ni-NTA

Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- MNNG

N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine

- PGM

Personal Genome Machine

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- RNAP

RNA polymerase

- SNPs

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- TSB

Tryptic soy broth

Additional file

Primers Used to Confirm NTML Strains. Table S2. Proteins identified as binding to the sigS promoter region in a biotin pull down assay. Table S3. Tn551 Insertions Resulting in Increased Expression of sigS. Table S4. Tn551 Insertions Resulting in Decreased Expression of sigS.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

WB performed experiments and drafted the manuscript. HM, CK, and SL performed experiments. RC performed whole genome sequencing and data analysis. LS conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Whittney N Burda, Email: wburda@mail.usf.edu.

Halie K Miller, Email: hakmille@ucsc.edu.

Christina N Krute, Email: ckrute@mail.usf.edu.

Shane L Leighton, Email: sleighto@mail.usf.edu.

Ronan K Carroll, Email: ronan1@usf.edu.

Lindsey N Shaw, Email: shaw@usf.edu.

References

- 1.Emori TG, Gaynes RP. An overview of nosocomial infections, including the role of the microbiology laboratory. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:428–442. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.4.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray S, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Dumyati G, Townes JM, Craig AS, Zell ER, Fosheim GE, McDougal LK, Carey RB, Fridkin SK, Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) MRSA Investigators Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:1763–1771. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archer GL. Staphylococcus aureus: a well–armed pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1179–1181. doi: 10.1086/520289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDougal LK, Fosheim GE, Nicholson A, Bulens SN, Limbago BM, Shearer JES, Summers AO, Patel JB. Emergence of resistance among USA300 methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus isolates causing invasive disease in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3804–3811. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00351-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helmann JD. The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Adv Microb Physiol. 2002;46:47–110. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(02)46002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lonetto MA, Brown KL, Rudd KE, Buttner MJ. Analysis of the Streptomyces coelicolor sigE gene reveals the existence of a subfamily of eubacterial RNA polymerase sigma factors involved in the regulation of extracytoplasmic functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:7573–7577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw LN, Lindholm C, Prajsnar TK, Miller HK, Brown MC, Golonka E, Stewart GC, Tarkowski A, Potempa J. Identification and characterization of sigma, a novel component of the Staphylococcus aureus stress and virulence responses. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller HK, Carroll RK, Burda WN, Krute CN, Davenport JE, Shaw LN. The extracytoplasmic function sigma factor sigmaS protects against both intracellular and extracytoplasmic stresses in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:4342–4354. doi: 10.1128/JB.00484-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morikawa K, Takemura AJ, Inose Y, Tsai M, Nguyen Thile T, Ohta T, Msadek T. Expression of a cryptic secondary sigma factor gene unveils natural competence for DNA transformation in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003003. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue H, Suzuki D, Asai K. A putative bactoprenol glycosyltransferase, CsbB, in Bacillus subtilis activates SigM in the absence of co-transcribed YfhO. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;436:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thackray PD, Moir A. SigM, an extracytoplasmic function sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis, is activated in response to cell wall antibiotics, ethanol, heat, acid, and superoxide stress. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:3491–3498. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.12.3491-3498.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sambrook J, Fritsche E, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning (a laboratory manual) New York: Cold Spring harbour Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horsburgh MJ, Aish JL, White IJ, Shaw L, Lithgow JK, Foster SJ. sigmaB modulates virulence determinant expression and stress resistance: characterization of a functional rsbU strain derived from Staphylococcus aureus 8325–4. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:5457–5467. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.19.5457-5467.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerout-Fleury AM, Shazand K, Frandsen N, Stragier P. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1995;167:335–336. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00652-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rivera FE, Miller HK, Kolar SL, Stevens SM, Shaw LN. The impact of CodY on virulence determinant production in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Proteomics. 2012;12:263–268. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolar SL, Antonio Ibarra J, Rivera FE, Mootz JM, Davenport JE, Stevens SM, Horswill AR, Shaw LN. Extracellular proteases are key mediators of Staphylococcus aureusvirulence via the global modulation of virulence-determinant stability. Microbiologyopen. 2013;2:18–34. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw LN, Aish J, Davenport JE, Brown MC, Lithgow JK, Simmonite K, Crossley H, Travis J, Potempa J, Foster SJ. Investigations into sigmaB-modulated regulatory pathways governing extracellular virulence determinant production in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6070–6080. doi: 10.1128/JB.00551-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kornblum J, Hartman BJ, Novick RP, Tomasz A. Conversion of a homogeneously methicillin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus to heterogeneous resistance by Tn551-mediated insertional inactivation. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1986;5:714–718. doi: 10.1007/BF02013311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carroll RK, Robison TM, Rivera FE, Davenport JE, Jonsson IM, Florczyk D, Tarkowski A, Potempa J, Koziel J, Shaw LN. Identification of an intracellular M17 family leucine aminopeptidase that is required for virulence in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbes Infect. 2012;14:989–999. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iordanescu S, Surdeanu M. Two restriction and modification systems in Staphylococcus aureus NCTC8325. J Gen Microbiol. 1976;96:277–281. doi: 10.1099/00221287-96-2-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adelberg EA, Pittard J. Chromosome transfer in bacterial conjugation. Bacteriol Rev. 1965;29:161–172. doi: 10.1128/br.29.2.161-172.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adelberg EA, Mandel M, Ching Chen GC. Optimal conditions for mutagenesis by N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine in K12. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1965;18:788–795. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(65)90855-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitra A, Fay PA, Vendura KW, Alla Z, Carroll RK, Shaw LN, Riordan JT. Sigma -dependent control of acid resistance and the locus of enterocyte effacement in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli is activated by acetyl phosphate in a manner requiring flagellar regulator FlhDC and the sigma antagonist FliZ. MicrobiologyOpen. 2014;3(4):497–512. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss A, Ibarra JA, Paoletti J, Carroll RK, Shaw LN. The delta subunit of RNA polymerase guides promoter selectivity and virulence in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2014;82:1424–1435. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01508-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koprivnjak T, Mlakar V, Swanson L, Fournier B, Peschel A, Weiss JP. Cation-induced transcriptional regulation of the dlt operon of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3622–3630. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.10.3622-3630.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carroll RK, Veillard F, Gagne DT, Lindenmuth JM, Poreba M, Drag M, Potempa J, Shaw LN. The Staphylococcus aureus leucine aminopeptidase is localized to the bacterial cytosol and demonstrates a broad substrate range that extends beyond leucine. Biol Chem. 2013;394:791–803. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oskouian B, Stewart GC. Repression and catabolite repression of the lactose operon of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3804–3812. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3804-3812.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soutourina O, Poupel O, Coppée J-Y, Danchin A, Msadek T, Martin-Verstraete I. CymR, the master regulator of cysteine metabolism in Staphylococcus aureus, controls host sulphur source utilization and plays a role in biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol. 2009;73:194–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xue T, You Y, Hong D, Sun H, Sun B. The Staphylococcus aureus KdpDE two-component system couples extracellular K + sensing and Agr signaling to infection programming. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2154–2167. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01180-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolar SL, Nagarajan V, Oszmiana A, Rivera FE, Miller HK, Davenport JE, Riordan JT, Potempa J, Barber DS, Koziel J, Elasri MO, Shaw LN. NsaRS is a cell-envelope-stress-sensing two-component system of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology. 2011;157:2206–2219. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.049692-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blake KL, Randall CP, O'Neill AJ. In vitro studies indicate a high resistance potential for the lantibiotic nisin in Staphylococcus aureus and define a genetic basis for nisin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2362–2368. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01077-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bose JL, Fey PD, Bayles KW. Genetic tools to enhance the study of gene function and regulation in Staphylococcus aureus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:2218–2224. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00136-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staron A, Sofia HJ, Dietrich S, Ulrich LE, Liesegang H, Mascher T. The third pillar of bacterial signal transduction: classification of the extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor protein family. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74:557–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheung A, Soutourina O, Dubrac S, Poupel O, Msadek T, Martin-Verstraete I. The Pleiotropic CymR regulator of Staphylococcus aureus plays an important role in virulence and stress response. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000894. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang X, Zheng L, Landwehr C, Lunsford D, Holmes D, Ji Y. Global regulation of gene expression by ArlRS, a two-component signal transduction regulatory system of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5486–5492. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5486-5492.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freeman ZN, Dorus S, Waterfield NR. The KdpD/KdpE two-component system: integrating K(+) homeostasis and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003201. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chitnis CE, Freeman ZN, Dorus S, Waterfield NR. The KdpD/KdpE two-component system: integrating K + homeostasis and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003201. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Durr H, Korner C, Muller M, Hickmann V, Hopfner KP. X-ray structures of the Sulfolobus solfataricus SWI2/SNF2 ATPase core and its complex with DNA. Cell. 2005;121:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Neill AJ. Staphylococcus aureus SH1000 and 8325–4: comparative genome sequences of key laboratory strains in staphylococcal research. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2010;51:358–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saxild HH, Andersen LN, Hammer K. Dra-nupC-pdp operon of Bacillus subtilis: nucleotide sequence, induction by deoxyribonucleosides, and transcriptional regulation by the deoR-encoded DeoR repressor protein. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:424–434. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.424-434.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuroda M, Tanaka Y, Aoki R, Shu D, Tsumoto K, Ohta T. Staphylococcus aureus giant protein Ebh is involved in tolerance to transient hyperosmotic pressure. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;374:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng AG, Missiakas D, Schneewind O. The giant protein Ebh is a determinant of staphylococcus aureus cell size and complement resistance. J Bacteriol. 2013;196:971–981. doi: 10.1128/JB.01366-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henze U, Sidow T, Wecke J, Labischinski H, Berger-Bachi B. Influence of femB on methicillin resistance and peptidoglycan metabolism in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1612–1620. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1612-1620.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshida A, Freese E. Enzymatic properties of alanine dehydrogenase of bacillus subtilis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1965;96:248–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrari E, Henner DJ, Yang MY. Isolation of an Alanine Racemase gene from bacillus subtilis and its use for plasmid maintenance in B. subtilis. Bio/Technology. 1985;3:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nbt1185-1003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Charlier D, Kholti A, Huysveld N, Gigot D, Maes D, Thia-Toong TL, Glansdorff N. Mutational analysis of Escherichia coli PepA, a multifunctional DNA-binding aminopeptidase. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:411–426. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]