Abstract

Wilson’s disease (WD) is an autosomal recessive inherited disorder of hepatic copper metabolism. WD can be present in different clinical conditions, with the most common ones being liver disease and neuropsychiatric disturbances. Most cases present symptoms at < 40 years of age. However, few reports exist in the literature on patients in whom the disease presented beyond this age. In this report, we present a case of late onset fulminant WD in a 58-year-old patient in whom the diagnosis was established clinically, by genetic analysis of the ATP7B gene disclosing rare mutations (G1099S and c.1707+3insT) as well as by high hepatic copper content. We also reviewed the relevant literature. The diagnosis of WD with late onset presentation is easily overlooked. The diagnostic features and the genetic background in patients with late onset WD are not different from those in patients with early onset WD, except for the age. Effective treatments for this disorder that can be fatal are available and will prevent or reverse many manifestations if the disease is discovered early.

Keywords: Wilson’s disease, Late onset, Fulminant, ATP7B gene mutations, Copper

Core tip: There are few reports in the literature on patients in whom Wilson’s disease presented well beyond the age of 40 years and much less when the presentation is fulminant. We present a 58-year-old patient with late onset fulminant Wilson’s disease and very rare mutations in the ATP7B gene. In addition, we review the relevant literature on late onset fulminant Wilson’s disease.

INTRODUCTION

Wilson’s disease (WD) is an autosomal recessive inherited disorder of hepatic copper metabolism caused by mutation of an intracellular copper transporter ATPase, ATP7B, that is mainly expressed in hepatocytes. Loss of ATP7B function results in reduced hepatic biliary copper excretion, reduced incorporation of copper into ceruloplasmin[1] and the accumulation of copper in many organs and tissues. WD can be present in different clinical conditions, with liver disease and neuropsychiatric disturbances being the most common ones. The diagnosis of WD relies on detection of Kayser-Fleischer rings, low ceruloplasmin, elevated urine and hepatic copper level, signs of liver and/or neurologic disease and associated histologic changes in the liver[1]. If untreated, WD results invariably in severe disability and death[1]. Available medical therapies and liver transplantation can be offered to patients with this fatal disorder. The early detection of the disease and prompt initiation of treatment to prevent disease progression and reverse pathologic findings if present are warranted[2]. The disease is common in children and young adults, and presents in most cases between the age of 3 and 40 years. However, there are few reports in the literature in whom the disease presented beyond this age[3-14], with some of them in the form of case reports[3-10]. Three case series included also older patients[11-13], and one large study by Ferenci et al[14] included 46 patients who became symptomatic at > 40 years of age. Thus, more attention is needed to identify older patients with WD. In this report, we present a case of late onset fulminant WD in a 58-year-old patient and reviewed the relevant literature.

CASE REPORT

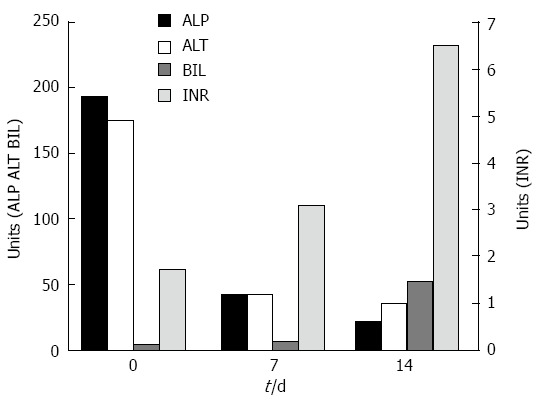

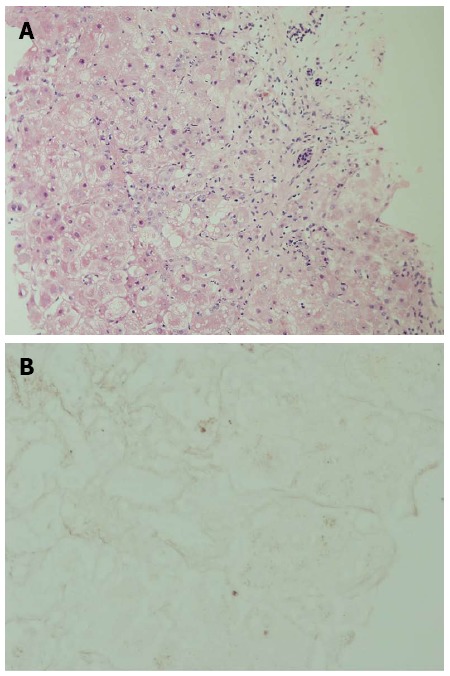

A 58-year-old morbid obese patient complained of fatigue and poor appetite for one year. In her physical examination she had leg edema and newly diagnosed ascites. She denied alcohol consumption and regular or under-the counter-medication use. Ultrasound investigation revealed a hyperechoic fatty liver, enlarged spleen and a moderate amount of ascitic fluid. Doppler examination revealed patent portal and hepatic veins. Laboratory data included: total bilirubin (Bil), 4 mg/dL (direct, 2.5 mg/dL); alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 194 U/L (normal, 115 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 112 U/L (normal, < 40 U/L); alanine transaminase (ALT), 175 U/L (normal, < 42 U/L); albumin, 2.8 g/L, international normalized ratio (INR), 1.7; hemoglobin, 12.1 g/L; white blood cell count, 5.5 × 109/L; and platelet count, 112 × 109/L. Blood sugar, urea, and creatinine were normal. Serological screening revealed that the patients tested negative for hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B core antigen, and hepatitis C virus. Serum titers of smooth muscle antibodies and nuclear and mitochondrial antibodies were negative. The patient was diagnosed as having cirrhosis due to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and was discharged with diuretic therapy. Several weeks later she was re-admitted with increasing fatigue, weakness and jaundice. Repeated blood tests demonstrated severe impairment in liver synthetic function: INR, 3.1; albumin, 2.5 g/L; and Bil, 6.7 mg/dL (direct, 4.5 mg/dL). Her hemoglobin was 12.8 g/L, white blood cell count 10.0 × 109/L, and platelet count 106 × 109/L. The condition of the patient deteriorated rapidly and her liver function tests were aggravated: AST, 91 U/L; ALT, 42 U/L; ALP, 21 U/L; Bil, 52 mg/dL; and INR, 6.5 (Figure 1). She developed renal failure (creatinine, 2.93 mg/dL) and grade 3 hepatic encephalopathy (ammonia, 180 micgr/dL) and was transferred to our intensive care unit. A tentative diagnosis of fulminant late onset WD was made and a transjugular liver biopsy was performed. Histological examination of liver tissue displayed acute hepatitis with bridging necrosis and advanced fibrosis, macro- and micro-vesicular steatosis (Figure 2A) and accumulation of copper binding proteins (Figure 2B). Hepatic copper content was 986 mcg/g dry weight (normal < 50 mcg/g dry weight). Serum ceruloplasmin level was 12 mg/dL. There was no evidence for the presence of a Kayser-Fleischer ring. To confirm the diagnosis of WD, we performed DNA sequence analysis of the ATP7B gene, which disclosed rare mutations: G1099S and c.1707+3insT. These findings were compatible with the definite diagnosis of WD with a fulminant course. The patient was transferred to a liver transplant center where molecular absorbent recycling system and plasmapheresis were performed and was urgently listed for status 1liver transplantation. However, the patient died several days later as no liver donor was available.

Figure 1.

Biochemical parameters and international normalized ratio. Serum ALP and ALT decreased while bilirubin level increased. The INR level increased dramatically, indicating the fulminant course of the disease. ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; ALT: Alanine transaminase; Bil: Bilirubin; INR: International normalized ratio.

Figure 2.

Histological evaluation of liver tissue (hematoxylin-eosin staining, × 20). A: Histological examination of liver tissue displayed acute hepatitis with bridging necrosis and advanced fibrosis, macro- and micro-vesicular steatosis; B: Using orcein (copper binding protein stain), accumulation of copper binding protein was revealed.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of fulminant late onset WD was established in our case mainly by the low ceruloplasmin level, the high hepatic copper content and the genetic analysis. However, the diagnosis of fulminant WD was deferred in our patient due to her age and the morbid obesity leading to the wrong assumption that her primary liver disease was related to NAFLD. Without urgent liver transplantation, acute liver failure (ALF) due to WD is invariably fatal[1]. Thus, rapid diagnosis of fulminant WD should prompt transplant listing. Korman et al[15] reported that utilizing conventional WD testing such as serum ceruloplasmin and/or serum copper levels are less sensitive and specific in identifying patients with ALF-WD than other available tests. It was suggested in that study that laboratory tests including alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin and serum aminotransferases provide the most rapid and accurate method for diagnosis of ALF due to WD. An AST:ALT ratio > 2.2 yielded a sensitivity of 94%, and a specificity of 86% and an ALP to total bilirubin ratio < 4 yielded a sensitivity of 94%, and a specificity of 96% for diagnosing fulminant WD[15]. Our patient fulfilled these criteria as her ALP to total bilirubin ratio was 0.4 and her AST/ALT ratio was 2.2, and the diagnosis of ALF-WD could be established using these simple criteria. The main reason that WD has been overlooked in our patient at the beginning was the morbid obesity and the NAFLD (detected by ultrasound and liver histology) that our patient suffered from. However, the most frequently observed hepatic histological lesion in WD is hepatic macro-steatosis and glycogenated nuclei[16], which are features that can be seen also in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. In a recently published study[17], the hepatic steatosis in WD was not induced by metabolic comorbidities but by the accumulation of copper in the liver tissue. However, metabolic alterations could be co-factors in the pathogenesis of steatosis in these patients. Thus, the presence of fatty liver should not exclude the diagnosis of WD.

WD may become symptomatic at any age and should be considered in any patient presenting with unclear hepatic or neurologic disease. Medical therapy includes several chelating agents and zinc salts[1,2]. In the largest study published so far[14], the diagnostic features and the genetic background in patients with late onset WD were not different from the overall cohort of 1223 patients with WD, except for age. Reviewing the literature on late onset WD, we have detected 70 reported cases (including our case): 8 case reports[3-10], 3 case series[11-13] and 1 large study[14] (Table 1). The definite diagnosis of WD was not achieved in all of the reported cases. A large variability was noted in the clinical presentation of WD (ranging from limited hepatic chronic or fulminant disease or central nervous system disease to disease that involves both organs), in the serum level of ceruloplasmin (ranging from normal to low serum level) and in the presence of a Kayser-Fleischer ring (Table 1). In all the reported cases that the liver copper content was measured, it was > 250 μg/g dry weight. The H1069Q mutation was the most frequently detected (Table 1). We have detected 6 cases (including our patient) that presented with a fulminant course. DNA sequence analysis of the ATP7B gene was not performed in these patients. However, in our patient we have detected rare mutations: the G1099S and the c.1707+3insT. These mutations have been reported so far only in the Greek population and at a frequency of 1% each[18]. This huge variability in the clinical presentation of WD reflects our limited knowledge on the natural history of WD. The phenotype is required to be defined as accurately as possible in genetic associated studies[19]. There are several explanations for the misdiagnosis of WD in older subjects. First, our diagnostic criteria that rely on the neurological symptoms, the presence of a Kayser-Fleischer ring, and a low ceruloplasmin concentration[1,2,20] are sometimes inaccurate to detect the disease. Plasma ceruloplasmin is often within the normal range and in some studies up to 50% of affected individuals with severe decompensated liver disease have normal ceruloplasmin level[2]. Kayser-Fleischer ring is absent at least in one-third of patients, and neurologic symptoms are absent in most[1,2,20]. Relying only on the diagnostic criteria can lead to misdiagnosis of WD at any age and not just in late onset. Additional laboratory data are helpful to establish the diagnosis, such as the increase in urinary copper excretion and the increased hepatic copper content, but these tests still have limitations[1,2]. Copper concentrations that are falsely low can be detected in hepatic specimens with extensive fibrosis and few parenchymal cells. In addition, greatly increased hepatic copper concentrations can be seen in long-term cholestasis[2]. Genetic testing is also now a diagnostic tool, but its application in the clinical routine is limited by the lack of general availability (cost) and the huge number of mutations[1,2,20]. Even in the largest study by Ferenci et al[14], based on clinical symptoms and laboratory findings, diagnosis was certain only in 39 (84.7%) of their patients. Other explanations for overlooking WD in older subjects are: WD may have a slowly progressing course as reported in 3 cases, of whom two presented at the age of 70 and 72 years (siblings)[8] and one presented at the age of 84 years[10]. A longer time delay from onset of symptoms until definitive diagnosis (3 years) is typically detected in patients with WD and neuropsychiatric symptoms than in patients with hepatic symptoms[21].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics at diagnosis of late onset Wilson's disease - literature review

| Ref. | n | Mean age (yr) | Diagnosis | Fulminant | Hepatic | Neurologic | Ceruloplasmin (mg/dL) | KayserFleischer ring | Mutation | Copper (μg) per gram liver dry weight |

| Fitzgerald et al[3] | 1 | 55 | Possible | No | Yes | No | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Członkowska et al[4] | 1 | 46 | NA | No | NA | Yes | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ross et al[5] | 1 | 57 | Definite | No | No | Yes | 14 | No | NA | 400 |

| Hefter et al[6] | 1 | 60 | Possible | No | No | Yes | 13 | No | NA | 356 |

| Dib et al[7] | 1 | 57 | Possible | No | No | No | 7 | No | NA | 1300 |

| Ala et al[8] | 2 | 70-72 | Definite | No | Yes | Yes | 37 | Yes | E1064A and H1069Q | 671 |

| Perri et al[9] | 1 | 60 | Definite | No | Yes | No | Normal | No | H1069Q and E1064A | 1021 |

| Członkowska et al[10] | 1 | 84 | Definite | No | Yes | No | 33.4 | Yes | H1069Q | NA |

| Danks et al[11] | 4 | 43-58 | Definite in 3 patients | Yes in 2 patients | Yes | No | 12-normal | No | NA | 717-1199 |

| Gow et al[12] | 5 | 44-58 | Definite | Yes in 2 patients | Yes | No | 14-37 | Yes in 2 patients | NA | 516-1526 |

| Pilloni et al[13] | 5 | 40-57 | NA | NA | yes | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ferenci et al[14] | 46 | 40-57 | 39 diagnosed on clinical grounds; 33 diagnosed by mutation, 5 patients diagnosis possible | Yes in 1 patient | Yes in 15 patients | Yes in 31 patients | < 20 mg/dL in 41 patients | Yes in 32 patients | H1069Q/H1069Q in 13, H1069Q/R969Q in 3, H1069Q/other in 4 patients | Liver copper> 250 in 13 of 17 biopsied patients |

| Current case | 1 | 58 | Definite | Yes | Yes | No | 12 | No | G1099S and c.1707+3insT | 986 |

In conclusion, the diagnosis of WD with late onset presentation is easily overlooked. There is considerable phenotypic variation in WD. Except for the age, the diagnostic features and the genetic background in patients with late onset WD are not different from those with early onset WD. Effective treatments are available that will prevent or reverse many manifestations of this disorder if the disease is discovered early.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

A 58-year-old female with a 1-year history of fatigue and poor appetite presented with newly diagnosed ascites.

Clinical diagnosis

Morbid obese, with leg edema and ascites.

Differential diagnosis

Decompensated cirrhosis due to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Laboratory diagnosis

Total bilirubin, 4 mg/dL (direct, 2.5 mg/dL); alkaline phosphatase, 194 U/L (normal, 115 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 112 U/L (normal, < 40 U/L); alanine transaminase, 175 U/L (normal, < 42 U/L); albumin, 2.8 g/L, international normalized ratio, 1.7; hemoglobin, 12.1 g/L; white blood cell count, 5.5 × 109/L; platelet count, 112 × 109/L. Serum ceruloplasmin level, 12 mg/dL.

Imaging diagnosis

Ultrasound investigation revealed a hyperechoic fatty liver, enlarged spleen and a moderate amount of ascitic fluid. Doppler examination revealed patent portal and hepatic veins.

Pathological diagnosis

Severe acute hepatitis with bridging necrosis and advanced fibrosis, macro- and micro-vesicular steatosis and accumulation of copper binding proteins. Hepatic copper content was 986 mcg/g dry weight (normal, < 50 mcg/g dry weight).

Treatment

The patient was transferred to a liver transplant center where molecular absorbent recycling system and plasmapheresis were performed and was urgently listed for status 1 liver transplantation. However, as no liver donor was available, the patient died.

Experiences and lessons

Wilson’s disease (WD) can have a late onset presentation. Without emergency liver transplantation, acute liver failure due to WD is invariably fatal. Therefore, rapid diagnosis of WD should aid prompt transplant listing.

Peer review

The diagnostic features and the genetic background in patients with late onset WD are not different from those with early onset WD, except for the age. If discovered early, effective treatments are available that will prevent or reverse many manifestations of this disorder that is fatal.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Lee HW S- Editor: Ding Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Rosencrantz R, Schilsky M. Wilson disease: pathogenesis and clinical considerations in diagnosis and treatment. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31:245–259. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1286056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ala A, Walker AP, Ashkan K, Dooley JS, Schilsky ML. Wilson’s disease. Lancet. 2007;369:397–408. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgerald MA, Gross JB, Goldstein NP, Wahner HW, McCall JT. Wilson’s disease (hepatolenticular degeneration) of late adult onset: report of case. Mayo Clin Proc. 1975;50:438–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Członkowska A, Rodo M. Late onset of Wilson’s disease. Report of a family. Arch Neurol. 1981;38:729–730. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1981.00510110089019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross ME, Jacobson IM, Dienstag JL, Martin JB. Late-onset Wilson’s disease with neurological involvement in the absence of Kayser-Fleischer rings. Ann Neurol. 1985;17:411–413. doi: 10.1002/ana.410170421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hefter H, Weiss P, Wesch H, Stremmel W, Feist D, Freund HJ. Late diagnosis of Wilson’s disease in a case without onset of symptoms. Acta Neurol Scand. 1995;91:302–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1995.tb07010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dib N, Valsesia E, Malinge MC, Mauras Y, Misrahi M, Calès P. Late onset of Wilson’s disease in a family with genetic haemochromatosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:43–47. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200601000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ala A, Borjigin J, Rochwarger A, Schilsky M. Wilson disease in septuagenarian siblings: Raising the bar for diagnosis. Hepatology. 2005;41:668–670. doi: 10.1002/hep.20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perri RE, Hahn SH, Ferber MJ, Kamath PS. Wilson Disease--keeping the bar for diagnosis raised. Hepatology. 2005;42:974. doi: 10.1002/hep.20893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Członkowska A, Rodo M, Gromadzka G. Late onset Wilson’s disease: therapeutic implications. Mov Disord. 2008;23:896–898. doi: 10.1002/mds.21985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danks DM, Metz G, Sewell R, Prewett EJ. Wilson’s disease in adults with cirrhosis but no neurological abnormalities. BMJ. 1990;301:331–332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6747.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gow PJ, Smallwood RA, Angus PW, Smith AL, Wall AJ, Sewell RB. Diagnosis of Wilson’s disease: an experience over three decades. Gut. 2000;46:415–419. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.3.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilloni L, Lecca S, Coni P, Demelia L, Pilleri G, Spiga E, Faa G, Ambu R. Wilson’s disease with late onset. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:180. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(00)80408-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferenci P, Członkowska A, Merle U, Ferenc S, Gromadzka G, Yurdaydin C, Vogel W, Bruha R, Schmidt HT, Stremmel W. Late-onset Wilson's disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1294–1298. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korman JD, Volenberg I, Balko J, Webster J, Schiodt FV, Squires RH, Fontana RJ, Lee WM, Schilsky ML. Screening for Wilson disease in acute liver failure: a comparison of currently available diagnostic tests. Hepatology. 2008;48:1167–1174. doi: 10.1002/hep.22446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ludwig J, Moyer TP, Rakela J. The liver biopsy diagnosis of Wilson’s disease. Methods in pathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:443–446. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/102.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liggi M, Murgia D, Civolani A, Demelia E, Sorbello O, Demelia L. The relationship between copper and steatosis in Wilson’s disease. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loudianos G, Lovicu M, Solinas P, Kanavakis E, Tzetis M, Manolaki N, Panagiotakaki E, Karpathios T, Cao A. Delineation of the spectrum of Wilson disease mutations in the Greek population and the identification of six novel mutations. Genet Test. 2000;4:399–402. doi: 10.1089/109065700750065162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferenci P. Phenotype-genotype correlations in patients with Wilson’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1315:1–5. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferenci P, Caca K, Loudianos G, Mieli-Vergani G, Tanner S, Sternlieb I, Schilsky M, Cox D, Berr F. Diagnosis and phenotypic classification of Wilson disease. Liver Int. 2003;23:139–142. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merle U, Schaefer M, Ferenci P, Stremmel W. Clinical presentation, diagnosis and long-term outcome of Wilson’s disease: a cohort study. Gut. 2007;56:115–120. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.087262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]