Abstract

Here, we developed a new Tartary buckwheat cultivar ‘Manten-Kirari’, whose flour contains only trace amounts of rutinosidase and lacked bitterness. The trace-rutinosidase breeding line ‘f3g-162’ (seed parent), which was obtained from a Nepalese genetic resource, was crossed with ‘Hokkai T8’ (pollen parent), the leading variety in Japan, to improve its agronomic characteristics. The obtained progeny were subjected to performance test. ‘Manten-Kirari’ had no detectable rutinosidase isozymes in an in-gel detection assay and only 1/266 of the rutinosidase activity of ‘Hokkai T8’. Dough prepared from ‘Manten-Kirari’ flour contained almost no hydrolyzed rutin, even 6 h after the addition of water, whereas the rutin in ‘Hokkai T8’ dough was completely hydrolyzed within 10 min. In a sensory evaluation of the flour from the two varieties, nearly all panelists detected strong bitterness in ‘Hokkai T8’, whereas no panelists reported bitterness in ‘Manten-Kirari’. This is the first report to describe the breeding of a Tartary buckwheat cultivar with reduced rutin hydrolysis and no bitterness in the prepared flour. Notably, the agronomic characteristics of ‘Manten-Kirari’ were similar to those of ‘Hokkai T8’, which is the leading variety in Japan. Based on these characteristics, ‘Manten-Kirari’ is a promising for preparing non-bitter, rutin-rich foods.

Keywords: Tartary buckwheat, breeding, bitterness, rutinosidase, genetic resources, quality, cross breeding

Introduction

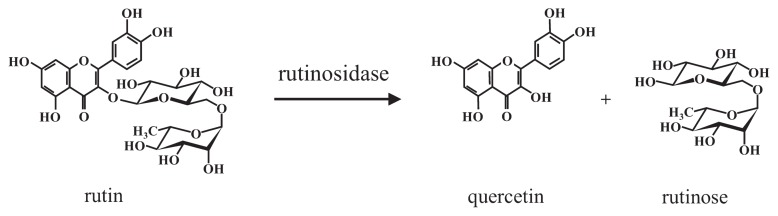

Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum Gaertn.) is cultivated in many countries and region, including China, Nepal, Russia, Europe and Japan. As the seeds of Tartary buckwheat contain approximately 100-fold higher amounts of rutin compared to common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench.), it is considered to be a rich dietary source of rutin (Ikeda et al. 2012, Kreft et al. 2006). Rutin is a type of flavonoid that is widely distributed in the plant kingdom (Couch et al. 1946, Fabjan et al. 2003, Haley and Bassin 1951, Sando and Lloyd 1924); however, buckwheat is the only known cereal to contain rutin in seeds. Rutin has numerous beneficial biological functions, including antioxidative (Awatsuhara et al. 2010, Jiang et al. 2007), antihypertensive (Matsubara et al. 1985) anti-inflammatory, and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activities (Li et al. 2009), and blood capillary strengthening properties (Griffith et al. 1944, Shanno 1946). Recently, rutin has focused because it reduces serum myeloperoxidasde and cholesterol levels (Wieslander et al. 2011), mucosal symptoms, headache, and tiredness (Wieslander et al. 2012). In addition to high rutin concentrations, however, Tartary buckwheat seeds also contain a high level of rutinosidase activity (Fig. 1) (Suzuki et al. 2002, Yasuda et al. 1992, Yasuda and Nakagawa 1994), which is capable of hydrolyzing rutin (approximately 1%–2% [w/w]) in the prepared flour within a few minutes after the addition of water. Therefore, the development of a low rutinosidase cultivar of Tartary buckwheat is desirable to maximize the health benefits of foods prepared from this grain.

Fig. 1.

Rutinosidase in Tartary buckwheat seeds converts rutin to quercetin and the disaccharide rutinose.

Tartary buckwheat seeds contain at least two rutinosidase isozymes, which have similar substrate specificities, Km, and optimum temperature and pH (Suzuki et al. 2002, Yasuda et al. 1992, Yasuda and Nakagawa 1994). Therefore, the expression of both isozymes must be suppressed to develop a low rutinosidase cultivar. In addition, Tartary buckwheat is traditionally known as ‘bitter buckwheat’ because its flour contains strong bitterness, a trait that limits its use in food products. To date, however, no non-bitter varieties of Tartary buckwheat with low rutinosidase activity have been developed. Recently, our research group identified a Tartary buckwheat plant with trace-rutinosidase activity from a genetic resource in Nepal (Suzuki et al. 2014). A breeding line from the plant, designated ‘f3g-162’, had no detectable rutinosidase activity in seeds using an in-gel detection method (Suzuki et al. 2014) and the prepared flour lacked bitterness. We determined that these characteristics were conferred by a single recessive gene, which was named rutinosidase-trace A (rutA). Despite the positive attributes of this line for food products, the maturing time of ‘f3g-162’ in Hokkaido, which is the largest production area of buckwheat in Japan, is markedly longer than that of the main variety of Tartary buckwheat, ‘Hokkai T8’, and therefore has very low relative yields.

In the present study, we attempted to develop a new Tartary buckwheat cultivar with agronomic characteristics that allow large-scale cultivation and whose flour has no bitterness and only trace amounts of rutinosidase activity.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials, cultivation and screening of trace-rutinosidase lines

Tartary buckwheat seeds were sown in the experimental field at the Memuro Upland Farming Research Station of the National Agriculture and Food Research Organization, Hokkaido Agricultural Research Center (Shinsei, Memuro, Kasai-Gun; longitude, 143°03′E; latitude, 42°55′N) during late May and early June under the following conditions: 4.8 m2 plot size, seeding density of 67 seeds/m2, 60-cm row spacing, three replications (small-scale performance test); 7.2 m2 plot size, seeding density of 150 seeds/m2, 60-cm row spacing, three replications (preliminary performance test); and 9.6 m2 plot size, seeding density of 150 seeds/m2, 60-cm row spacing, three replications performance test. In all three field tests, the fertilizer applied contained 0.6 kg N, 1.8 P2O5, 1.4 K2O, and 0.5 kg MgO per 10 are. The Tartary buckwheat plants were harvested, threshed using a threshing machine and seeds were stored at 4°C.

Standard assay for in-vitro rutinosidase activity and determination of rutin concentration

A standard assay for rutinosidase activity was performed by measuring the quercetin concentration in a reaction mixture using high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). The standard assay mixture consisted of 50 mM acetate-NaOH buffer (pH 5.0 at 4°C), 20% (v/v) methanol, and 0.2% (w/v) rutin in a final volume of 0.05 ml. The reaction was performed at 37°C and was stopped by the addition of 0.2 ml methanol (Suzuki et al. 2002). Rutin concentrations in seeds and dough were measured using HPLC, as previously described (Suzuki et al. 2002).

Detection of rutinosidase isozymes by native PAGE with a rutin-copper complex

Rutinosidase isozymes were detected on native-PAGE gels using a rutin-copper complex, as previously described (Suzuki et al. 2004). Briefly, Tartary buckwheat seeds or flour were homogenized with extraction buffer containing 10% (v/v) glycerol and 0.01% (w/v) Bromophenol blue (BPB) in 50 mM acetate-NaOH buffer (pH 5.0). The resulting crude enzyme solution was loaded onto a 7.5% (w/v) native-PAGE gel and then separated under non-denaturing conditions using a slab gel apparatus (Bio-Rad). After electrophoresis, the gel was equilibrated with 50 mM acetate- NaOH buffer (pH 5.0 at 4°C) containing 20% (v/v) methanol for 10 min. The equilibrated gel was stained in 50 mM acetate-NaOH buffer (pH 5.0 at 4°C), 20% (v/v) methanol, 0.6% (w/v) rutin, and 5 mM CuSO4 for 20 min (Suzuki et al. 2004) and was then washed thoroughly with water.

Breeding of ‘Manten-Kirari’

We previously screened approximately 200 genetic resources and 300 mutant lines, including seeds of Tartary buckwheat varieties collected in Nepal, and identified several plants with trace-rutinosidase activity (Suzuki et al. 2014). Seeds were harvested from each trace-rutinosidase plant, and the isozyme composition of rutinosidase was investigated using the in-gel detection method described above. Among plants with seeds that lacked rutinosidase isozymes, line ‘f3g-162’ was selected as a trace-rutinosidase line for progeny analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Breeding process of Manten-Kirari

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Generation | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | F9 | |

| Numbers of materials | 85 plants | 633 lines | 176 lines | 17 lines | 17 lines | 13 lines | 2 lines | 1 line | 1 line | |

| Numbers of selections | 17 lines | 633 plants | 176 lines | 17 lines | 17 lines | 13 lines | 2 lines | 1 line | 1 line | 1 line |

|

| ||||||||||

| Breeding procedure | crossing f3g162 × Hokkai T8 | propagation of seeds | selection of low-rutinosidase lines | small scale performance test | propagation of seeds | small scale performance test | preliminary perfprmance test | performance test | performance test | propagation of seeds |

|

| ||||||||||

| Name | 09CF6-10 | Mekei T27 | Mekei T27 | Manten-Kirari | ||||||

Artificial crosses between the trace-rutinosidase line ‘f3g-162’ (as a seed parent) and the normal rutinosidase variety ‘Hokkai T8’ (as a pollen parent) were performed by hot-water emasculation (Mukasa et al. 2007). Harvested F1 seeds were sown, and plants were individually harvested to obtain F2 seeds, respectively. The rutinosidase activity of F2 progeny was investigated, and plants with trace-rutinosidase activity were selected for further propagation. The agronomical characteristics of progeny up to the F7 generation were evaluated, and the most promising line was named ‘Mekei T27’. This line was continually propagated and was submitted for variety registration in 2012 under the name ‘Manten-Kirari’ (Table 1). In 2014, ‘Manten-Kirari’ was officially registered as a variety of Tartary buckwheat with the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

Investigation of rutin hydrolysis in dough

To prepare dough, 100 g Tartary buckwheat flour was thoroughly mixed with 45 mL water, and was then stored at 5°C for 10 min, 1 h, 2 h and 6 h. The dough was then mixed with 80% (v/v) methanol containing 0.1% (v/v) phosphoric acid to inactivate rutinosidase activity and extract rutin. The mixture was centrifuged. The obtained supernatant was passed through a 0.45-μm PTFE hydrophobic filter (Advantec, Tokyo, Japan), and the rutin concentration was then measured by HPLC as previously described (Suzuki et al. 2002). The ‘residual rutin ratio’ was expressed relative to the rutin concentration in flour measured before the addition of water.

Evaluation of bitterness of Tartary buckwheat flour

To evaluate and compare the bitterness of flour prepared from the ‘Manten-Kirari’ variety, which was established by a cross between a trace-rutinosidase line and the normal rutinosidase variety ‘Hokkai T8’, sensory analysis was performed by 29 panelists, who consisted of men ranging from 34 to 55 years old, and women ranging from 29 to 56 years old. For the analysis, each panelist placed ‘Manten-Kirari’ flour (1.0 g) in their mouth and tasted the sample for 1 min. After removing the flour and washing their mouth sufficiently with water, the panelists repeated the process with a sample of ‘Hokkai T8’ flour. The panelists then assessed the bitterness of each flour sample and classified the samples based on the degree of bitterness into two categories: ‘bitter’ (bitter or extremely bitter) or ‘not bitter’ (no or little bitterness).

Results

Breeding of ‘Manten-Kirari’

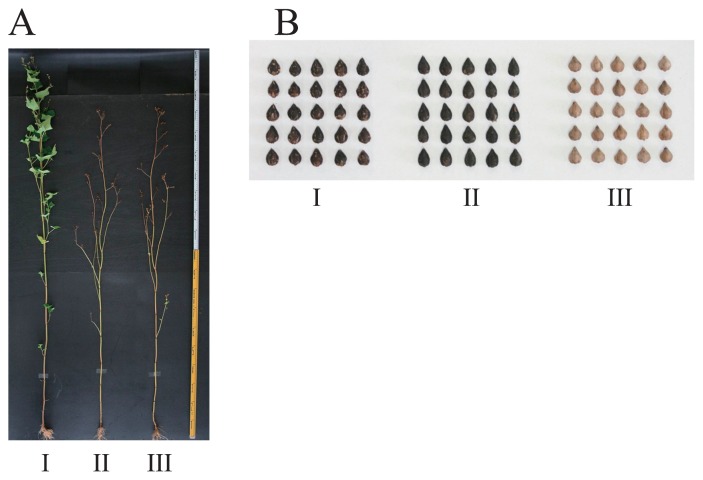

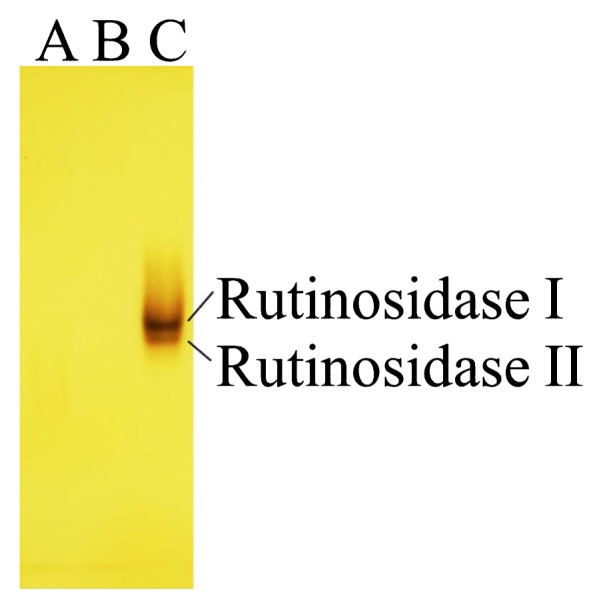

The ‘f3g-162’ line of Tartary buckwheat was previously identified as a promising breeding material for generating a buckwheat cultivar with trace-rutinosidase activity (Suzuki et al. 2014). However, because its agronomic characteristics, particularly its extremely late maturation period and low grain yield, were not suited for the climate of Hokkaido (Fig. 2A), we performed a crossing between ‘f3g-162’ and ‘Hokkai T8’, the main Tartary buckwheat variety in Japan. One of the progeny of this cross, designated ‘Manten-Kirari’, exhibited agronomic characteristics that were similar to ‘Hokkai T8’ (described below) and also had trace-rutinosidase activity in seeds. In addition, similar to the seed parent ‘f3g-162’, no rutinosidase isozymes were detected in ‘Manten-Kirari’ using an in-gel detection method (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Pictures of plants and seeds of the ‘Manten-Kirari’ variety of Tartary buckwheat. A: Picture of plants at harvesting time of ‘Manten-Kirari’. B: Pictures of seeds. I: ‘f3g-162’ (seed parent), II: ‘Manten-Kirari’, and III: ‘Hokkai T8’ (pollen parent).

Fig. 3.

Detection of rutinosidase isozymes using an in-gel detection method. Rutinosidase isozymes in the seeds of A: f3g-162 (trace-rutinosidase line; seed parent), B: Manten-Kirari, and C: Hokkai T8 (normal rutinosidase variety; pollen parent) were detected using an in-gel detection method involving the native-PAGE separation of crude protein extracts.

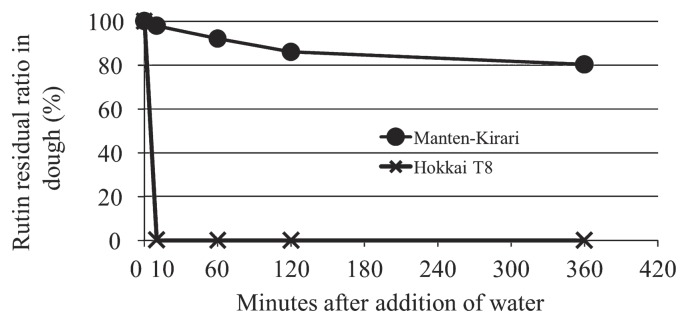

Rutin hydrolysis and bitterness of dough

As the ‘Manten-Kirari’ variety had trace-rutinosidase activity in an in-vitro assay, we examined and compared the hydrolysis of rutin during the storage of dough prepared from ‘Manten-Kirari’ with that of ‘Hokkai T8’. In ‘Hokkai T8’ dough, rutin was completely hydrolyzed within 10 min after the addition of water (Fig. 4). In contrast, rutin was only partially hydrolyzed in ‘Manten-Kirari’ dough, even 6 h after the addition of water (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Time course analysis of the residual rutin ratio in dough of the Manten-Kirari and ‘Hokkai T8’ varieties. For the analysis, Tartary buckwheat flour (100 g) was thoroughly mixed with water (45 mL), and the prepared dough was stored at 5°C for 10 min, 1 h, 2 h and 6 h. The rutin concentration was then measured using HPLC.

We also investigated the bitterness of flour prepared from seeds of ‘Manten-Kirari’ by conducting sensory evaluations. In the sensory analysis of ‘Hokkai T8’ flour, 27 of 29 panelists detected strong bitterness, whereas none of the panelists reported bitterness in ‘Manten-Kirari’ flour (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of bitterness in dough

| Bitterness | Number of people | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Bitter | Not bitter | |

| Manten-Kirar | 0 | 29 |

| Hokkai T8 | 27 | 2 |

Agronomical characteristics of ‘Manten-Kirari’

The agronomic characteristics of the ‘Manten-Kirari’ variety were evaluated by performance test (Table 3). In Hokkaido prefecture, the optimal sowing period for buckwheat is between late May and early June; therefore, we evaluated the characteristics of plants sown during this period. Compared to its seed parent ‘f3g-162’, ‘Manten-Kirari’ had an earlier maturing time, lower plant height, and higher grain yield, flour milling percentage, and rutin concentration. The agronomic characteristics of ‘Manten-Kirari’ were similar to those of ‘Hokkai T8’; however, the rutin concentration in seeds was higher in ‘Manten-Kirari’. In addition, the in-vitro rutinosidase activities of ‘Manten-Kirari’ and ‘f3g-162’ were two orders of magnitude lower than that of varieties with normal rutinosidase activity, including ‘Hokkai T8’ (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of performance test

| Variety name | Sowing time | Flowering time | Maturing time | Growing period | Plant Height | Stem diameter | Number of blanches | Number of flower clusters | Number of nodes | Lodging degreea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| month. day | month. day | month. day | days | cm | mm | number/plant | number/plant | number/plant | ||

| Manten-Kirari | 5.19 | 7.7 | 8.11 | 84 | 152 ab | 4.5 a | 5.3 a | 29.2 a | 16.0 a | 0.6 a |

| Hokkai T8 | 7.7 | 8.12 | 85 | 159 a | 4.7 a | 5.8 a | 27.2 a | 15.9 a | 1.2 a | |

| f3g-162 | 7.14 | not reached | – | 229 b | 5.5 b | 7.9 b | 53.1 b | 21.8 b | 0.2 a | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Manten-Kirari | 6.3 | 7.11 | 8.16 | 74 | 168 a | 4.8 a | 5.4 a | 28.3 a | 16.6 a | 1.7 a |

| Hokkai T8 | 7.11 | 8.16 | 74 | 169 a | 4.6 a | 4.5 a | 31.5 a | 15.9 a | 2.5 a | |

| f3g-162 | 7.19 | not reached | – | 232 b | 5.2 a | 8.1 b | 49.0 b | 22.9 b | 0.0 a | |

| Variety name | Total weight | Yield | Ratio to HokkaiT8 | Shattering seed weight | Thousand seeds weight | One liter weight of seeds | Flour milling percentatge | Rutin concentration | Rutinnosidase activity | Husk color |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| kg/10 a | kg/10 a | % | kg/10 a | g | g/L | % | mg/100 g flour | nkat/g seed | ||

| Manten-Kirari | 584 a | 248 a | 107 | 0.9 a | 17.5 a | 646 a | 62.8 a | 1,500 b | 0.533 a | Black |

| Hokkai T8 | 612 a | 231 a | 100 | 1.4 a | 18.5 a | 669 a | 62.8 a | 1,020 a | 507 b | Brown |

| f3g-162 | 913 b | 28 b | 12 | 0.1 a | 17.6 a | 532 b | 57.7 b | 1,120 a | 0.436 a | Black |

|

| ||||||||||

| Manten-Kirari | 606 a | 216 a | 97 | 0.9 a | 17.4 b | 629 b | 61.2 a | 1,390 b | 0.472 a | Black |

| Hokkai T8 | 623 a | 222 a | 100 | 1.1 a | 18.4 a | 663 a | 62.1 a | 1,200 a | 541 b | Brown |

| f3g-162 | 888 b | 32 b | 14 | 0.2 a | 17.9 a | 585 c | 59.7 b | 1,013 a | 0.446 a | Black |

Data are means of 2010 and 2011.

0: none–5: much.

Different alphabets indicate values are significantly different at P < 0.05 (Ryan’s multiple range test).

Discussion

Breeding of ‘Manten-Kirari’

As Tartary buckwheat is difficult to cross-breed due to its small flower size, simple selection and mutation breeding methods (Morishita et al. 2001) have been used for this species, and several unique and promising varieties have been developed (Kim et al. 2007, Morishita et al. 2010, Suzuki et al. 2009). The variety of Tartary buckwheat developed in the present study, ‘Manten-Kirari’, is the first to be bred using a cross-breeding method, which involved hot water emasculation (Mukasa et al. 2007). As this cross-breeding approach had a 90% success rate, it is clearly effective for the crossing of Tartary buckwheat.

In the cultivation and distribution of buckwheat, the contamination of ‘Manten-Kirari’ seeds with those of ‘Hokkai T8’ would be highly problematic because the latter contains high levels of rutinosidase and would result in the hydrolysis of rutin and generation of strong bitterness in the prepared flour. As the husk of ‘Hokkai T8’ is brown, whereas that of ‘Manten-Kirari’ is black (Fig. 2), contaminating ‘Hokkai T8’ seeds could easily be removed using a color-sorting machine, which is widely available in buckwheat-producing areas and milling companies. In addition, the cultivation of ‘Manten-Kirari’ on a large scale would necessitate the development of various discrimination techniques, such as those based on DNA markers, to evaluate the contamination of flour.

To date, breeding materials of Tartary buckwheat, such as semi-dwarf varieties have been developed by gamma ray-induced mutations in Tartary buckwheat (Morishita et al. 2010). Semi-dwarfness is a promising trait for improving the agronomic characteristics of ‘Manten-Kirari’ because of low plant height and strong lodging resistance (Kasajima et al. 2012, 2013, Morishita et al. 2010). Therefore, further breeding to cross ‘Manten-Kirari’ with a semi-dwarf cultivar would be effective to develop a new cultivar of Tartary buckwheat.

Rutin hydrolysis in dough and bitterness of Tartary buckwheat flour

Because ‘Manten-Kirari’ seeds have trace-rutinosidase activity, we hypothesized that foods prepared from ‘Manten-Kirari’ flour would contain markedly higher levels of rutin and only trace bitterness compared to those of ‘Hokkai T8’. We confirmed that only a small amount of rutin in ‘Manten-Kirari’ dough was hydrolyzed to quercetin and rutinose (Fig. 4). Because rutinosidase is not active in flour or food under dried conditions or after heat treatment, rutin-rich and non-bitter foods can be made with ‘Manten-Kirari’ dough if it is dried and/or heated within several hours of being prepared. We assumed that 6 h is sufficient to process buckwheat dough for use in many food types, such as noodles, breads, and confectioneries. We confirmed that buckwheat noodles made from ‘Manten-Kirari’ flour contained a large amount of rutin and no bitterness, whereas those made from ‘Hokkai T8’ flour contained only low concentrations of rutin and had a strong bitter taste (data not shown).

Agronomic characteristics of ‘Manten-Kirari’

Although ‘f3g-162’ is a promising breeding material for generating trace-rutinosidase varieties of buckwheat, its agronomic characteristics are not suitable for cultivation in the Hokkaido region, which is the largest production area of Tartary buckwheat in Japan. In the ‘Manten-Kirari’ variety developed here, many agronomic characteristics of ‘f3g-162’ (seed parent) were improved, including a shortening of the growth period, smaller plant height, and increased grain yields. Among the improved characteristics, we considered that the shortening of the growth period is the most important factor for the large-scale cultivation of ‘Manten-Kirari’. In the Hokkaido region, the non-frost period extends from late May to late November, and typhoons most frequently occur after August. Therefore, the optimal cultivation period of buckwheat in Hokkaido is limited to between late May and late August. However, because the ‘f3g-162’ line was originally collected in eastern Nepal, where Tartary buckwheat is generally cultivated as an autumn ecotype and is typically sown in late June (Namai and Gotoh 1994, Namai et al. 1994), it is unlikely that ‘f3g-162’ would reach maturity if cultivated in the Hokkaido region. On the other hand, ‘Manten-Kirari’ reaches maturity in middle August same as ‘Hokkai T8’ (Table 3). Therefore, ‘Manten-Kirari’ is suitable for cultivation in Hokkaido region.

In the breeding of common buckwheat, it is difficult to change ecotypes because of the allogamous nature of this plant; for example, two or three back crossings between the progeny of a cross between summer and autumn types were typically required to select for lines that reached maturation in the summer. In addition, the presence of numerous dominant genes that control the ecotype of common buckwheat (Hara et al. 2011) is also likely related to the difficulty of selection in this species. Therefore, before starting to breed for a low rutinosidase cultivar of Tartary buckwheat, we speculated that two or three crossings would be required to shorten the maturation period of ‘f3g-162’. Notably, however, we were able to select promising lines after only a single crossing. The self-pollinating characteristics of Tartary buckwheat may have contributed to the more rapid maturation of these new lines. This information will be useful for the future breeding of Tartary buckwheat.

In addition to the maturation period, the other examined agronomic characteristics of ‘Manten-Kirari’ were similar to those of ‘Hokkai-T8’, although several characteristics, such as thousand-seed weight and one-liter weight of seeds, significantly differed between the two varieties. However, these differences are not expected to limit the practical use of ‘Manten-Kirari’ in agriculture.

In Japan, commercial cultivation of ‘Manten-Kirari’ was started in 2012, and several noodle and confectionary products containing ‘Manten-Kirari’ flour are commercially available. We confirmed that rutin is not hydrolyzed and that no bitterness is evident in these products. As an alternative to the use of buckwheat varieties with trace-rutinosidase activity such as ‘Manten-Kirari’, flour or seeds from normal rutinosidase varieties can be heat treated to inactivate rutinosidase. However, the heat inactivation of rutinosidase requires a long treatment duration, which substantially deteriorates the product quality and physical properties, including the flavor and color, and increases production costs. Therefore, the ‘Manten-Kirari’ variety is advantageous for the production of non-bitter foods compared to varieties with normal rutinosidase activity, as it does not require heat treatment.

In the northern limit of the upland farming area in Japan, the number of unused and abandoned fields is rapidly increasing due to a decline in field workers as the previous generation of farmers advances in age. In this upland area, commonly farmed crops such as wheat, sugar beet, beans, and potato cannot sufficiently grow due to the shortened growth season. However, because Tartary buckwheat has a relatively short growth period of only 80–90 days, it can be cultivated in these northerly farming areas. In general, Tartary buckwheat can be cultivated with relatively little labor because it does not require additional fertilizer (Sharama 2005) and is also suitable for repeated cultivation as it is resistant to replant disease. In addition, because low temperatures often occur during the flowering period in upland farming areas, the yield of common buckwheat is low because the activity of pollen-disseminating insects is markedly reduced. Under such conditions, however, Tartary buckwheat can still be pollinated due to its self-pollinating characteristics. Due to these advantageous properties, Tartary buckwheat is one of the only crops that can grow in this region in Japan. However, the strong bitterness associated with Tartary buckwheat has limited its use in foods. For this reason, ‘Manten-Kirari’ is a promising variety of Tartary buckwheat for the preparation of rutin-rich and non-bitter foods because it can be cultivated even in the northern limits of farming regions in Japan.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. T. Saruwatari, Mr. N. Murakami, Mr. S. Nakamura, Mr. K. Abe, Mr. T. Yamada, Mr. T. Takakura, Mr. T. Fukaya, Mr. M. Oizumi, Mr. T. Hirao, and Mr. K. Suzuki for their assistance in the field. We also thank Ms. K. Fujii, Ms. M. Hayashida, and Ms. T. Ando for technical assistance. Screening of the trace-rutinosidase line was performed as part of the NIAS ‘Gene bank Project’ of the National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences, Japan. Breeding and evaluation of ‘Manten-Kirari’ was partly supported by ‘Research and Development Projects for Application in Promoting New Policy of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries’ and ‘grant from the Research Project on Development of Agricultural Products and Foods with Health-promoting benefits (NARO), Japan’.

Literature Cited

- Awatsuhara, R., Harada, K., Maeda, T., Nomura, T. and Nagao, K. (2010) Antioxidative activity of the buckwheat polyphenol rutin in combination with ovalbumin. Mol. Med. Rep. 3: 121–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch, J.F., Naghski, J. and Krewson, C.F. (1946) Buckwheat as a source of rutin. Science 103: 197–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabjan, N., Rode, J., Kosir, I.J., Wang, Z., Zhang, Z. and Kreft, I. (2003) Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum Gaertn.) as a source of dietary rutin and quercitrin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51: 6452–6455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, J.Q., Couch, J.F. and Lindauer, A. (1944) Effect of rutin on increased capillary fragility in man. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 55: 228–229. [Google Scholar]

- Haley, T.J. and Bassin, M. (1951) The isolation, purification and derivatives of plant pigments related to rutin. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 40: 111–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara, T., Iwata, H., Okuno, K., Matsui, K. and Ohsawa, R. (2011) QTL analysis of photoperiod sensitivity in common buckwheat by using markers for expressed sequence tags and photoperiod-sensitivity candidate genes. Breed. Sci. 61: 394–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, K., Ikeda, S., Kreft, I. and Rufa, L. (2012) Utilization of Tartary buckwheat. Fagopyrum 29: 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P., Burczynski, F., Campbell, C.J., Pierce, G., Austria, J.A. and Briggs, C.J. (2007) Rutin and flavonoid contents in three buckwheat species Fagopyrum esculentum, F. tataricum, and F. homotropicum and their protective effects against lipid peroxidation. Food Res. Int. 40: 356–364. [Google Scholar]

- Kasajima, S., Itoh, H., Yoshida, H., Suzuki, T., Mukasa, Y., Morishita, T. and Shimizu, A. (2012) Growth, yield, and dry matter production of a gamma ray-induced semi dwarf mutant of Tartary buckwheat. Fagopyrum 29: 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kasajima, S., Endo, A., Itoh, H., Yoshida, H., Suzuki, T., Mukasa, Y., Morishita, T. and Shimizu, A. (2013) Internode elongation patterns in semi dwarf and standard-height genotypes of Tartary buckwheat. Fagopyrum 30: 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.J., Maeda, T., Sarker, M.Z., Takigawa, S., Matsuura-Endo, C., Yamauchi, H., Mukasa, Y., Saito, K., Hashimoto, N., Noda, T.et al. (2007) Identification of anthocyanins in the sprouts of buckwheat. J. Agric. Food Chem. 55: 6314–6318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft, I., Fabjan, N. and Yasumoto, K. (2006) Rutin content in buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) food materials and products. Food Chem. 98: 508–512. [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara, Y., Kumamoto, H., Iizuka, Y., Murakami, T., Okamoto, K., Miyake, H. and Yokoi, K. (1985) Structure and hypotensive effect of flavonoid glycosides in Citrus unshiu peelings. Agric. Biol. Chem. 49: 909–914. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.Q., Zhou, F.C., Gao, F., Bian, J.S. and Shan, F. (2009) Comparative evaluation of quercetin, isoquercetin and rutin as inhibitors of alpha-glucosidase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57: 11463–11468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita, T., Yamaguchi, H. and Degi, K. (2001) The dose response and mutation induction by gamma ray in buckwheat. The proceeding of the 8th ISB: 334–338. [Google Scholar]

- Morishita, T., Mukasa, Y., Suzuki, T., Shimizu, A., Yamaguchi, H., Degi, K., Aii, J., Hase, Y., Shikazono, N., Tanaka, A.et al. (2010) Characteristics and inheritance of the semi dwarf mutants of Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum Gaertn.) induced by gamma ray and ion beam irradiation. Breed. Res. 12: 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mukasa, Y., Suzuki, T. and Kim, S.J. (2007) Inheritance of a dark red cotyledonal trait in Tartary buckwheat. Fagopyrum 24: 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Namai, H. and Gotoh, T. (1994) Title in Japanese. Norin Suisan Gijutu Joho Kyokai Norinsuisan Gene Bank no Kisyohseibutsu toh no Idenshigen Chousa Shuushuu Itaku Jigho Seika Hokokusho IV: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Namai, H., Gotoh, T. and Chaudhary, N.K. (1994) Present situation of tatary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum) cultivation in the middle mountainous area “Mahabharat mountainous area “Mahabharat mountain range” of the eastern Nepal. Ikushyugaku Zassi 44: 266. [Google Scholar]

- Sando, C.E. and Lloyd, J.U. (1924) The isolation and identification of rutin from the flowers of elder (Sambucus canadensis L.). J. Biol. Chem. 58: 737–745. [Google Scholar]

- Shanno, R.L. (1946) Rutin: A new drug for the treatment of increased capillary fragility. Am. J. Med. Sci. 211: 539–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharama, V.K. (2005) A preliminary study on fertilizer management in buckwheat. Fagopyrum 22: 95–97. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T., Honda, Y., Funatsuki, W. and Nakatsuka, K. (2002) Purification and characterization of flavonol 3-glucosidase, and its activity during ripening in Tartary buckwheat seeds. Plant Sci. 163: 417–423. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T., Honda, Y., Funatsuki, W. and Nakatsuka, K. (2004) In-gel detection and study of the role of flavonol 3-glucosidase in the bitter taste generation in tartary buckwheat. J. Sci. Food Agric. 84: 1691–1694. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T., Watanabe, M., Iki, M., Aoyagi, Y., Kim, S.J., Mukasa, Y., Yokota, S., Takigawa, S., Hashimoto, N., Noda, T.et al. (2009) Time-course study and effects of drying method on concentrations of γ-aminobutyric acid, flavonoids, anthocyanin, and 2″-hydroxynicotianamine in leaves of buckwheats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57: 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T., Morishita, T., Mukasa, Y., Takigawa, S., Yokota, S., Ishiguro, K. and Noda, T. (2014) Discovery and genetic analysis of non-bitter Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum Gaertn.) with trace-rutinosidase activity. Breed. Sci. 64: 339–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieslander, G., Fabjan, N., Vogrinčič, M., Kreft, I., Janson, C., Spetz-Nyström, U., Vombergar, B., Tagesson, C., Leanderson, P. and Norbäck, D. (2011) Eating buckwheat cookies is associated with the reduction in serum levels of myeloperoxidase and cholesterol: A double blind crossover study in day-care center staffs. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 225: 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieslander, G., Fabjan, N., Vogrinčič, M., Kreft, I., Vombergar, B. and Norbäck, D. (2012) Effect of common and Tartary buckwheat consumption on mucosal symptoms, headache and tiredness: A double-blind crossover intervention study. J. Food Agric. Environ. 10: 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda, T., Masaki, K. and Kashiwagi, T. (1992) An enzyme degrading rutin in Tartary buckwheat seeds. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. Technol. 39: 994–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda, T. and Nakagawa, H. (1994) Purification and characterization of rutin-degrading enzymes in Tartary buckwheat seeds. Phytochem. 37: 133–136. [Google Scholar]