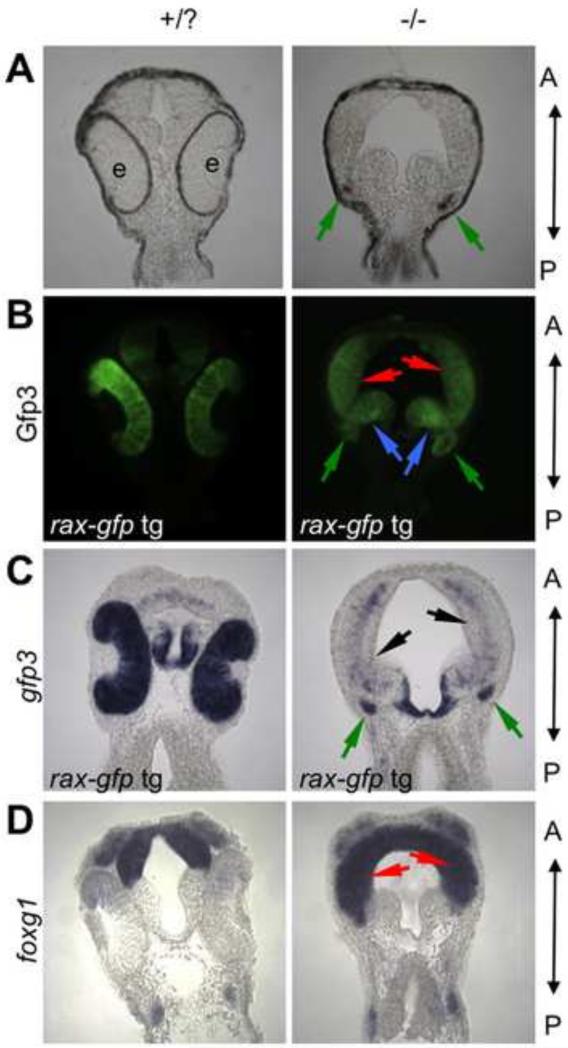

Figure 5. Presumptive retinal tissue is transformed into diencephalic and telencephalic tissue in the rax mutant.

(A-C) Genetic labeling of retinal fated tissue in wildtype and mutant embryos. A transgenic line expressing gfp3 under control of the rax-promoter was crossed into the rax mutant background. (A) Brightfield image of frontal sections from stage 32 embryos. (B) Gfp3 protein expression detected via immunostaining. (C) Transgene (gfp3) mRNA expression visualized via in situ hybridization. (D) Telencephalic marker foxg1 mRNA expression visualized via in situ hybridization. In all panels, A marks the anterior and P the posterior. Red arrows mark regions of telencephalic expansion, and blue arrows mark diencephalic expansion into eye region. Green arrows mark the small rudiment that is pigmented (A) in this specific section and continues to express Gfp3 (B-C). Although Gfp3 protein can still be readily discerned, the mRNA is mostly absent in the expanded telencephalic region (black arrows). Five embryos from each phenotype (wild-type or mutant eye morphology) and treatment were scored for these analyses; expression patterns were highly stereotyped within each phenotype. A minimum of two embryos for each phenotype and treatment were then chosen for serial sectioning and imaging.