Smoking is the number one preventable cause of death in the United States and half of the people who currently smoke will die from smoking-related causes (World Health Organization, 2007). Although smoking cessation treatments are effective, individuals with depressive disorders/symptoms (Weinberger et al., 2012a, 2012b, 2013) and substance use disorders (SUDs; Baca & Yahne, 2009; Okoli & Khara, 2011; Prochaska et al., 2004) have particular difficulties quitting smoking. Unfortunately, treatment providers in mental health and addiction treatment settings rarely advise their clients to quit smoking, or provide cessation treatments (Guydish et al., 2011; Knudsen et al., 2010; Prochaska, 2010), often because they believe cessation could cause relapse to other substances or increases in psychiatric symptoms (Fuller et al., 2007; Prochaska et al., 2006). However, multiple studies demonstrate that smoking cessation does not interfere with substance use (e.g., Prochaska et al., 2004; Tsoh et al., 2011), or mental health outcomes (e.g., Lawn & Pols, 2005; Prochaska et al., 2008). Despite negative consequences associated with smoking, few successful cessation treatments have been developed specifically targeting individuals with co-occurring depressive and SUDs.

Cessation programs tested with smokers with depressive disorders/symptoms include treatments focusing on motivation (Hall et al., 2006), mood management via cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; Batra et al., 2010; Hall et al., 1998), and reducing depression via CBT (Brown et al., 2001; 2007). A recent meta-analysis indicates components targeting mood management improve outcomes (Gierisch et al., 2012), suggesting it is essential to target mood improvements in individuals with depressive disorders attempting to quit smoking. However, despite significant advances in smoking cessation therapies for individuals with depressive disorders/symptoms, low cessation rates continue to be observed (e.g. Weinberger et al., 2013).

Treatments targeting individuals with SUDs have utilized CBT, contingency management, and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (see Okoli et al., 2010 review); group counseling (Reid et al., 2008); behavioral therapy (Joseph et al., 2004); and content focused on depressive symptoms (see Baca & Yahne, 2009 review). Barriers to cessation have been noted in these studies, where long-term abstinence is relatively rare. For example, only 5% of individuals with SUDs who received NRT + CBT were abstinent at a 13-week follow-up (Reid et al., 2008), while 7-day point prevalence abstinence rates were 15.5% at a 3-month follow-up among individuals with alcohol use disorders receiving NRT + behavioral therapy (Joseph et al., 2004). Thus, it is necessary to formulate new strategies to better target the needs of substance users.

Recently, researchers have targeted increases in positive affect via behavioral activation (BA) to increase abstinence from cigarettes and drugs. MacPherson and colleagues (2010) demonstrated that a BA-enhanced (see Treatment section and Table 1 for a description of BA) treatment for smokers (BATS), which included CBT for smoking cessation (CBT), NRT, and BA, significantly improved outcomes among individuals with elevated depressive symptoms. In their study, individuals receiving BATS were 2.26 times more likely to be abstinent post-treatment than individuals receiving CBT + NRT.

Table 1.

BA-DAS Session Content

Session 1: Introduction to BA and Smoking Cessation

|

| Session 2: Life Areas, Values, and Activities |

| Session 3: Quit Day: Monitoring Progress |

Session 4: Reviewing Progress and Enlisting Social Support

|

Session 5: Post-Treatment Plan

|

Indicates treatment components that are repeated at all subsequent sessions

Further, individuals in BATS had significantly greater decreases in depressive symptoms over time. BA has also been used to decrease depressive symptoms and improve substance use outcomes among individuals with SUDs (Daughters et al., 2008; Magidson et al., 2011). Taken together, these findings suggest a BA-enhanced treatment could address the multiple factors associated with poor cessation outcomes among smokers with SUDs and elevated depressive symptoms.

Method

Participants

The current study tested Behavioral Activation for Drug Abusing Smokers (BA-DAS; Table 1) among 12 African Americans (see Table 2) with SUDs and elevated depressive symptoms in residential substance use treatment. Inclusion criteria: 18–65 years-old, Beck Depression Inventory score ≥ 7, scored ≥ 5 on a 10 point scale for motivation to quit, and smoked ≥ 5 cigarettes/day for ≥ 1 year.

Table 2.

Baseline Demographics, Smoking History, and Affective Variables.

| M | SD | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| % Female | 5 (41.70) | ||

| % Black/African American | 12 (100.00) | ||

| % Court-mandated | 4 (33.30) | ||

| Average age | 39.18 | 10.25 | |

| Average treatment length (in days) | 34.50 | 17.53 | |

| Education* | |||

| Middle school graduate | 1 (8.30) | ||

| Some high school | 1 (8.30) | ||

| High school graduate/GED | 2 (16.70) | ||

| Some college | 5 (41.70) | ||

| Average household income | |||

| $0–9,909 | 3 (25.00) | ||

| $10,000–19,999 | 2 (16.70) | ||

| $20,000–29,999 | - | ||

| $30,000+ | 4 (33.30) | ||

| Smoking History Variables | |||

| Number of year smoking | 18.27 | 10.95 | |

| FTND | 5.18 | 2.36 | |

| Average weekly cigarettes pre-treatment | 96.95 | 92.97 | |

| Average weekly cigarettes post-treatment | 12.89 | 22.13 | |

| Affective Variables | |||

| Baseline BDI-II | 13.55 | 9.02 | |

| Post-treatment BDI-II | 6.67 | 8.47 | |

Not all percentages add to 100 because of missing data

Treatment

BA-DAS included key elements of CBT for smoking cessation (see Fiore et al., 2008), NRT (Nicoderm CQ 24-hour transdermal nicotine patch), and BA to target depressive symptoms (MacPherson et al., 2010). Treatment consisted of five 60–90 minute individual counseling sessions over 2 ½ weeks. BA components included: daily activity and smoking monitoring, identification of life areas (e.g., Relationships, Education) and values (broad descriptions of how individuals want to live within particular life areas), selection of activities enabling clients to live according to their values, creation of an activities schedule, and enlistment of social support via behavioral contracts (Lejuez et al., 2011; see Table 1). Therapists were four clinical psychology doctoral students who were trained extensively and received weekly supervision.

Measures

Clients reported their smoking for the 90 days prior to baseline and through four weeks post-quit via the Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1979; 1996), a reliable and valid self-report measure. TLFB reports were compared to biochemical assessments of abstinence (10ppm carbon monoxide cutoff via Vitalograph Breathco monitor). The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996) was used to determine clients’ depressive symptoms. A paper-based survey was created to determine participants’ treatment satisfaction. Presence of current SUDs was confirmed with the SCID-IV (First et al., 1995).

Results

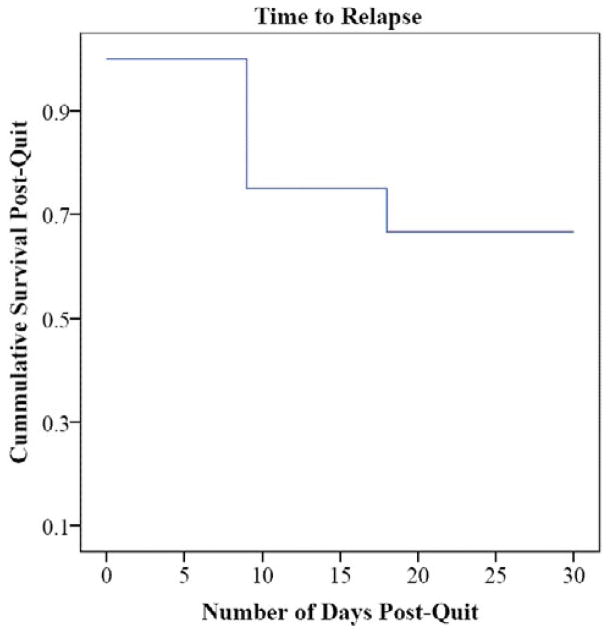

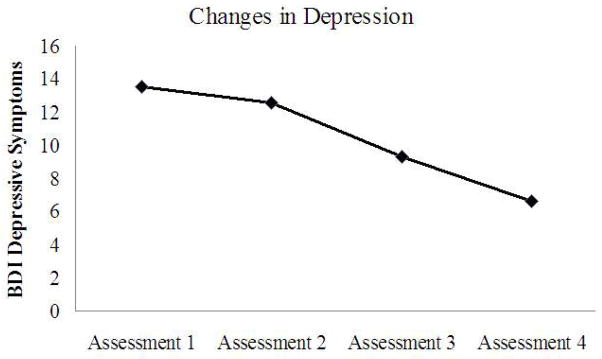

Four of the twelve participants were unreachable at the four-week follow-up. At the four-week follow-up, four of the eight participants assessed had CO levels < 10ppm, indicating abstinence (on quit day, seven of the eight participants assessed had CO levels < 10ppm; four participants did not provide CO levels because of administrator error). Of the total sample, 66.67% had not relapsed to smoking (defined as 5+ cigarettes/day for 3 days in a row; Shiffman et al., 2006) at the four-week follow-up (unreachable participants were coded as having relapsed at the prior assessment point), with a mean survival time of 23 days (see Figure 1). The average number of cigarettes consumed weekly pre-treatment was significantly higher than the average number consumed at the four-week follow-up t(8) = 2.37, p = .045 (Table 2). BDI scores decreased significantly from baseline to post-treatment t(8) = 2.49, p = .038 (see Table 2 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Survival Curve

Figure 2.

Depression Graph

Discussion

These preliminary results demonstrate the benefits of adding BA to smoking cessation interventions for individuals with substance use disorders and co-occurring depressive symptoms. Within our sample, 66.7% of participants had CO levels indicative of abstinence four weeks post-quit, as compared to 7.8% at a comparable time point in Saxon and colleagues’ (2003) study. Furthermore, participants had particularly low relapse rates during the four weeks post-quit and reduced their cigarette consumption significantly. This suggests BA-DAS may benefit participants during the time when they are most vulnerable to relapse (Brown, et al., 2001; Prochaska et al., 2004). In future work, it will be important to examine whether decreases in depressive symptoms, as a function of BA, explain decreases in cigarette consumption over treatment.

There are a number of limitations of this pilot, including the lack of a contact-time matched control condition, small sample size, missing follow-up and CO data for some participants, and the short follow-up period. In future work, it will be important to test this intervention within a randomized control trial with longer follow-up periods. Despite these limitations, there are a number of strengths of this study, including cessation benefits within this particularly difficult to treat population, high treatment satisfaction, and significant decreases in depressive symptoms over treatment. This provides an important basis for future work to examine BA-enhanced smoking cessation treatments in difficult-to-treat populations.

References

- Baca CT, Yahne CE. Smoking cessation during substance abuse treatment: What you need to know. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36(2):205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Brown G, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory II manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Kahler CW, Niaura R, Abrams DB, Sales SD, Ramsey SE, Miller IW. Cognitive–behavioral treatment for depression in smoking cessation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(3):471–480. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.3.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Niaura R, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Strong DR, Kahler CW, Abrantes AM, Miller IW. Bupropion and cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression in smoking cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(7):721–730. doi: 10.1080/14622200701416955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters S, Braun A, Sargeant M, Reynolds E, Hopko D, Blanco C, Lejuez CW. Effectiveness of a brief behavioral treatment for inner-city illicit drug users with elevated depressive symptoms: The Life Enhancement Treatment for Substance Use (LETS Act!) Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(1):122–129. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v69n0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Smith SS, Jorenby DE, Baker TB. The effectiveness of the nicotine patch for smoking cessation: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271:1940–1947. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.24.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller BE, Guydish J, Tsoh J, Reid MS, Resnick M, Zammarelli L, McCarty D. Attitudes toward the integration of smoking cessation treatment into drug abuse clinics. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierisch JM, Bastian LA, Calhoun PS, McDuffie JR, Williams JW., Jr Smoking cessation interventions for patients with depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis [serial online] Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2012;27(3):351–360. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1915-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Tajima B, Chan M, Delucchi KL, Ziedonis D. Measuring smoking knowledge, attitudes and services (S-KAS) among clients in addiction treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;114:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Tsoh JY, Prochaska JJ, Eisendrath S, Rossi JS, Redding CA, Gorecki JA. Treatment for cigarette smoking among depressed mental health outpatients: A randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(10):1808–1814. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph A, Willenbring M, Nugent S, Nelson D. A randomized trial of concurrent versus delayed smoking intervention for patients in alcohol dependence treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(6):681–691. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Studts JL, Boyd S, Roman PM. Structural and cultural barriers to the adoption of smoking cessation services in addiction treatment organizations. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2010;29:294–305. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2010.489446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn S, Pols R. Smoking bans in psychiatric inpatient settings? A review of the research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39(10):866–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1614.2005.01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Hopko DR, Acierno R, Daughters SB, Pagoto SL. Ten year revision of the brief behavioral activation treatment for depression: Revised treatment manual. Behavior Modification. 2011;35(2):111–161. doi: 10.1177/0145445510390929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson L, Tull MT, Matusiewicz AK, Rodman S, Strong DR, Kahler CW, Lejuez CW. Randomized controlled trial of behavioral activation smoking cessation treatment for smokers with elevated depressive symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(1):55–61. doi: 10.1037/a0017939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magidson JF, Gorka SM, MacPherson L, Hopko DR, Blanco C, Lejuez CW, Daughters SB. Examining the effect of the Life Enhancement Treatment for Substance Use (LETS ACT) on residential substance abuse treatment retention. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(6):615–623. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoli CC, Khara M. Smoking cessation among persons with co-occurring substance use disorder and mental illness. Journal of Smoking Cessation. 2011;6(1):58–64. doi: 10.1375/jsc.6.1.58. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okoli C, Khara M, Procyshyn R, Johnson J, Barr A, Greaves L. Smoking cessation interventions among individuals in methadone maintenance: A brief review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;38(2):191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JJ. Failure to treat tobacco use in mental health and addiction treatment settings: A form of harm reduction? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;110(3):177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J, Delucchi K, Hall S. A meta-analysis of smoking cessation interventions with individuals in substance abuse treatment or recovery. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(6):1144–1156. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JJ, Fromont SC, Louie AK, Jacobs MH, Hall SM. Training in tobacco treatments in psychiatry: A national survey of psychiatry residency training directors. Academy of Psychiatry. 2006;30:372–378. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.30.5.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JJ, Hall SM, Tsoh JY, Eisendrath S, Rossi JS, Redding CA, Rosen AB, Meisner M, Humfleet GL, Gorecki JA. Treating tobacco dependence in clinically depressed smokers: Effect of smoking cessation on mental health functioning. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:446–448. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MS, Fallon B, Sonne S, Flammino F, Nunes EV, Jiang H, Rotrosen J. Smoking cessation treatment in community-based substance abuse rehabilitation programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35(1):68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxon AJ, Baer JS, Davis TM, Sloan KL, Malte CA, Fitzgibbons K, Kivlahan DR. Smoking cessation treatment among dually diagnosed individuals: Preliminary evaluation of different pharmacotherapies. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5(4):589–596. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000118702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Scharf DM, Shadel WG, Gwaltney CJ, Dang Q, Paton SM, Clark DB. Analyzing milestones in smoking cessation: Illustration in a nicotine patch trial in adult smokers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(2):276–285. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Validity of self-reports in three populations of alcoholics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;46:901–907. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.46.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: A calendar method for assessing alcohol and drug use. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoh JY, Chi FW, Mertens JR, Weisner CM. Stopping smoking during first year of substance use treatment predicted 9-year alcohol and drug treatment outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;114:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Mazure CM, Morlett A, McKee SA. Editor’s choice: “Two Decades of Smoking Cessation Treatment Research on Smokers with Depression: 1990–2010”. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2013;15(6):1014–1031. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Pilver CE, Desai RA, Mazure CM, McKee SA. The relationship of dysthymia, minor depression, and gender to changes in smoking for current and former smokers: Longitudinal evaluation of the U.S. population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012a doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Pilver CE, Desai RA, Mazure CM, McKee SA. The relationship of major depressive disorder and gender to changes in smoking for current and former smokers: Longitudinal evaluation in the US population. Addiction. 2012b;107(10):1847–1856. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Health Report 2007: A safer future: Global public health security in the 21st century. 2007 Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241563444_eng.pdf.