Abstract

Psychotic symptoms have been associated with post-traumatic stress disorder and war experiences. However, the relationships between types of war experiences, the onset and course of psychotic symptoms, and post-war hardships in child soldiers have not been investigated. This study assessed whether various types of war experiences contribute to psychotic symptoms differently and whether post-war hardships mediated the relationship between war experiences and later psychotic symptoms. In an ongoing longitudinal cohort study (the War-Affected Youths Survey), 539 (61% male) former child soldiers were assessed for psychotic symptoms, post-war hardships, and previous war experiences. Regression analyses were used to assess the contribution of different types of war experiences on psychotic symptoms and the mediating role of post-war hardships in the relations between previous war experiences and psychotic symptoms. The findings yielded ‘witnessing violence’, ‘deaths and bereavement’, ‘involvement in hostilities’, and ‘sexual abuse’ as types of war experiences that significantly and independently predict psychotic symptoms. Exposure to war experiences was related to psychotic symptoms through post-war hardships (β = .18, 95% confidence interval = [0.10, 0.25]) accounting for 50% of the variance in their relationship. The direct relation between previous war experiences and psychotic symptoms attenuated but remained significant (β = .18, 95% confidence interval = [0.12, 0.26]). Types of war experiences should be considered when evaluating risks for psychotic symptoms in the course of providing emergency humanitarian services in post-conflict settings. Interventions should consider post-war hardships as key determinants of psychotic symptoms among war-affected youths.

Keywords: Former child soldiers, post-war hardships, psychotic symptoms, war experiences

The burden of mental health problems in the aftermath of war forms a major public health problem. Former child soldiers are among those severely affected by war in countries such as Sierra Leone, Liberia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Uganda (Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers, 2008; Machel, 2001). In Northern Uganda, an estimated 25,000 children were abducted and conscripted into the ranks of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) where about 85% of the rebel fighters were children (Schubert, 2006; The United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF], 1998). In captivity, the abductees lived in constant terror and fear of attacks from government soldiers and threats of death and diseases (Amone-P’Olak, 2007; Angucia, 2010; Ehrenreich, 1997). In addition, the abductees were tortured, sexually abused, and used as human shields against the firepower of the government army (Amone-P’Olak, 2009; Ovuga, Oyok, & Moro, 2008). Furthermore, LRA rebel commanders forced the abductees to perpetrate killing, mutilation, torture, raiding, and the burning of villages in a strategy known as ‘burning the bridge’ (Amone-P’Olak, 2004; Derluyn, Broekaert, Schuyten, & De Temmerman, 2004; Okello, Onen, & Musisi, 2007). Abductees were forced to commit atrocities against each other and against their own communities to deter them from escaping from rebel captivity and to secure their loyalty and bondage to the rebel organization (Amone-P’Olak, 2004; Derluyn et al., 2004; Okello, Onen, & Musisi, 2007). Despite this strategy, many abducted children (now youths) escaped from captivity and were reunited with their parents or guardians where they continue to experience mental health problems (Amone-P’Olak et al., 2013).

Post-war mental health problems are not only widespread but are linked to significant impairment (Amone-P’Olak, Garnefski, & Kraaij, 2007; Bayer, Klasen, & Adam, 2007; Derluyn et al., 2004; Okello, Onen, & Musisi, 2007). Although a wide variety of mental health problems have been associated with war, psychotic symptoms have been considered in very few studies.

Psychotic symptoms are thought to result from a complex interplay of biopsychosocial factors, including childhood trauma (Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman, & Bebbington, 2001). Given this link with extreme stressors, we examined how war experiences might be a risk factor for psychotic symptoms. While war experiences have been linked to psychotic phenomena in a handful of studies (e.g., Kinzie & Boehnlein, 1989), the multiple direct and indirect pathways that link such experiences to psychotic symptoms are poorly understood. War experiences such as killings, torture, and mutilation can directly lead to survivors of war hearing voices of the dead victims of war-related conflict or seeing dead bodies even when others cannot see the dead bodies (Kinzie & Boehnlein, 1989), in a manner similar to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). For example, in the war in Northern Uganda, former child soldiers were exposed to dead bodies, were forced to kill, torture, or mutilate fellow abductees and civilians (Amone-P’Olak, 2009; Angucia, 2010; Ehrenreich, 1998). Consequently, it is possible that former child soldiers may experience psychotic symptoms.

Indirectly, war is a precipitating and perpetuating risk factor for many mental health problems, including mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders which predispose to drug and substance abuse (alcohol, marijuana, khat), which in turn, are also linked to psychotic symptoms (Odenwald et al., 2005). The few extant studies on war experiences and psychotic symptoms show that psychoses are linked to co-morbid risk factors such as substance abuse and PTSD (Bayer et al., 2007; Coentre & Power, 2011). A study of Somali refugees in London reported that one in five Somalis (most fled because of war and insecurity in their country) were found to be psychotic (Bhui et al., 2003). This may have been related to the fact that the majority of the participants also reported chewing the leaves of khat (Cathaedulis), a drug known to induce psychosis (Odenwald et al., 2005). Similarly, PTSD and psychosis have been reported to be co-morbid in victims of the Pol Pot regime in Cambodia (Kinzie & Boehnlein, 1989). In Northern Uganda, war experiences have been associated with elevated levels of PTSD among former child soldiers (Amone-P’Olak et al., 2007; Bayer et al., 2007; Derluyn et al., 2004). It is therefore possible that the elevated levels of PTSD in former child soldiers in Northern Uganda may also be a risk factor for psychotic symptoms. Likewise, the aftermath of war in Northern Uganda may be associated with drug and alcohol abuse (Bayer et al., 2007; Ezard et al., 2011) which is also known to predispose to psychotic symptoms. Therefore, different war experiences can relate to psychotic symptoms directly and indirectly through post-war contexts.

Although the direct associations between war experiences and psychotic symptoms are documented, the indirect path accounting for the continued experience of psychotic symptoms remains poorly understood. Yet, it is possible that the effects of previous war experiences on psychotic symptoms are mediated by post-war hardships and difficulties. These post-war hardships and difficulties include disproportionate levels of poverty, community and domestic violence, insecurity, eviction from family land, inadequate housing and health care, stigma and discrimination, lack of social support, and insufficient financial resources for basic necessities like soap, salt, or sugar, all of which exacerbate existing mental health problems (Al-Krenawi, Lev-Wiesel, & Sehwail, 2007; Amone-P’Olak, Stochl, et al., 2014; Betancourt, Agnew-Blais, et al., 2010; Betancourt et al., 2013; Fernando, Miller & Berger, 2010; Miller, Omidian, Rasmussen, Yaqubi, & Daudzai, 2008; Miller & Rasmussen, 2010). We used mediation analyses in the current investigation because the War-Affected Youths Survey (WAYS) study retrospectively assessed war experiences of more than 6 years ago, post-war experiences in the past year and current psychotic symptoms. Therefore, in terms of temporal order (the most important consideration for mediation analyses), the requirement for a mediation model is satisfied.

Theoretical and conceptual framework

Social stress theory hypothesizes that stressors and resources act as mediators in the relationships between various stressful life events on the one hand and poor health outcomes on the other (Aneshensel, 1992). The hypothesis suggested by this model posits that environmental stressors and resources such as unemployment, drug or substance abuse, housing or economic difficulties, and lack of money for basic necessities act as mediators in the relationship between stressful life events (e.g., war experiences) and health outcomes (e.g., psychotic symptoms). The hypothesis is that stressful life events are causally related to environmental stressors, which in turn, perpetuate health outcomes such as the experience of psychotic symptoms. Upon return to their communities, former child soldiers experience lowered social status as a result of prejudice and fear from community members. Subsequently, they may not be gainfully employed and may resort to drug or substance abuse to cope with the trauma of war. This stigma may lead to greater experiences of stress (in the form of discrimination) and reduced access to protective resources, which may, in turn, combine with internal distress to influence poor mental health outcomes. It is also possible that environmental stressors and resources serve to buffer this risk (Aneshensel & Phelan, 1999). For example, the negative effects of stressful life events (e.g., wars) on health outcomes such as psychotic symptoms can be buffered by environmental resources such as gainful employment opportunities, adequate and sanitary housing, and access to health care. Therefore, the social stress theory can be adapted to illuminate the processes characterizing the relationship between war experiences, post-war environmental stressors, and experiencing psychotic symptoms. Within the culture of the local community in which this study was conducted, killing innocent people was considered an abomination. Whether justified or not, it is believed that killing led to guilt, shame, and anxiety (Opiyo & Ovuga, 2014). The spirit of the dead haunts the killer by appearing as a ghost or talking to the killer. To appease the spirit of the dead, a killer must ask for forgiveness, pay reparation, and perform rituals to chase the spirit of the dead away; failure to do so may lead to a wide array of symptoms similar to PTSD and psychotic symptoms (Opiyo & Ovuga, 2014).

Using data from a longitudinal cohort study of former child soldiers in Northern Uganda (see cohort profile – Amone-P’Olak et al., 2013), we reported on a cross-sectional analysis of data using robust measures of demographic characteristics, war experiences, post-war hardships, and psychotic symptoms among formerly abducted children. We hypothesized that past war experiences would be associated with psychotic symptoms and that post-war hardships mediate the relations between previous war experiences and psychotic symptoms. Even though general war experiences are related to later psychotic symptoms (Kinzie & Boehnlein, 1989), we were unaware of any research that attempted to delineate the extent to which exposure to various types of war experiences predicted psychotic symptoms simultaneously in the same analyses. Therefore, in order to develop interventions to mitigate the effects of war experiences on psychotic symptoms, there is a need to understand the path from different types of war experiences to psychotic symptoms by delineating the contribution of different types of war experiences and the role of post-war contextual factors such as post-war hardships (unemployment, poverty, poor accommodation, drug and substance abuse, etc.) in explaining psychotic symptoms among formerly abducted children and other war-affected populations.

The specific objectives of this study were threefold: (1) to assess the extent to which war experiences individually predicted psychotic symptoms, (2) to investigate the independent contribution of different types of war experiences to predicting psychotic symptoms in univariable and multivariable regression models, and (3) to quantify the extent to which the relation between general war experiences and psychotic symptoms were mediated by post-war hardships and difficulties.

Method

Study design

Although the WAYS study utilizes a longitudinal cohort design, the design for the present analyses was cross-sectional. War experiences were assessed retrospectively, but post-war difficulties and hardships and psychotic symptoms were assessed for occurrence in the past year.

Participants

Participants in the ongoing WAYS study are former child soldiers who were abducted and lived in rebel captivity for significant periods of time. The major aim of the WAYS study is to assess individual, family, and community contextual risk and protective factors that influence the long-term trajectory of mental health problems in war-affected youths in Northern Uganda. Cluster sampling was employed to recruit participants in the study. A list of eligible former child soldiers was compiled by UNICEF for the most affected districts of in Northern Uganda. In these districts are sub-districts, where formerly abducted children from the villages were sampled. The list compiled by UNICEF was previously used to allow formerly abducted children to receive assistance from non-governmental organizations (NGOs), including UNICEF itself. Assistance included household items such as mattresses, blankets, cooking utensils, basins, etc. and clothes to help them resettle in communities after return from captivity. Thus, we assumed the list to be complete, inclusive, and fairly accurate. From the lists of members of these groups, the following inclusion criteria were used for this study: (1) a history of abduction by rebels, (2) lived in rebel captivity for at least 6 months, and (3) aged between 18 and 25 years. Those who met the above inclusion criteria were invited through their local council leaders to participate in the study. Of the 650 formerly abducted children who were invited to participate, data were collected from 539 (83%). The cohort profile is described in detail elsewhere (Amone-P’Olak et al., 2013). Baseline data were collected between June 2011 and September 2011. The data presented in this article are drawn from the baseline data.

Instruments

The instruments used for data collection were back-translated from English to Luo, the native language of the participants, by experts from the Department of English at Gulu University who are fluent in both the English language and Luo. This was to reduce the possibility of loss of meaning often associated with difficulties of translating from one language to the other. Thereafter, the instrument was pilot-tested and modified for cultural relevance and sensitivity.

To assess individual exposures to various war experiences, we used items from the UNICEF B&H (Bosnia and Herzegovina) Post-war Screening Survey (UNICEF, 2010). The questionnaire was adapted by our research team to better capture the local context of the war in Northern Uganda. For example, items on knowledge of, witnessing, and being sexually abused were added. The adapted instrument contained 52 items and captured 12 war-related experiences including direct personal harm (6 items, for example, serious injuries), witnessing general war violence (11 items, for example, massacres or raids on villages), sexual abuse (1 item), involvement in hostilities (2 items, for example, ‘Did you fight in the army or warring faction?’), separation (2 items), bereavement (7 items, for example, death of parents, siblings, or extended family members), material loss (4 items), physical threat to self (5 items), harm to loved ones (4 items), physical threat to relatives or loved ones (4 items), displacement (5 items), and drug and substance abuse (1 item). War experiences were binary coded for occurrence (1) versus absence (0) and summed, yielding the total number of war events experienced. We chose these war experiences because we were interested in exploring the particular effect of forms of severe violence common in war-affected youths on psychosocial outcomes such as psychotic symptoms. The war experiences have been described in detail elsewhere (Amone-P’Olak et al., 2013).

The following four items addressing psychotic symptoms (i.e., hallucinations, delusions, and persecutory feelings) were used in this study: (1) sometimes I hear voices or see things other people do not see, (2) sometimes I feel that I have special powers, (3) sometimes I think that people are listening to my thoughts or watching me when I am alone, and (4) sometimes I think that people are against me. The four items covered hallucinations, delusions, and persecutory feelings, all common features of psychotic symptoms. The items were scored ranging from 0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, and 3 = always. The psychotic symptoms scale had good psychometric properties (Cronbach’s alpha = .71).

The UNICEF B&H Post-war Screening Survey (UNICEF, 2010) was used to assess post-war hardships. The questionnaire consisted of 26 items and asked about hardships and difficulties experienced during the past 6 months. The items included economic difficulties (e.g., ‘did you lack money for basic necessities like soap, salt, or sugar?’), being physically assaulted (by known or unknown persons) and accommodation concerns (e.g., inadequate, overcrowded, or unsanitary conditions unfit for people to live in). Each question was binary coded for presence (1) versus absence (0) and the total score would range from 0 to 26. The Kuder–Richardson coefficient of reliability (KR20) was used to ascertain the internal consistency for these binary items. In this study, the Kuder–Richardson coefficient of reliability was .83.

A demographic inventory specifically designed for this study was used to collect information on sex, age, duration in captivity, parental status, and number of children.

Procedures

Research assistants for the WAYS study were all university graduates fluent in English and the native language of the participants. They received extensive and intensive training in data gathering techniques such as interviewing skills and administration of questionnaires. The research assistants administered questionnaires to participants from trading centres, community halls, and participants’ homes. The questionnaire took 30–45 min to complete.

Statistical analyses

Square root transformation was used to improve normality for variables that were not normally distributed. Demographic characteristics of the study population and bivariate correlations between variables were computed and tabulated. Univariable and multivariable regression analyses were computed to assess the contributions of different types of war experiences in predicting psychotic symptoms. Overlaps among types of war events were addressed in a multivariate regression analysis in which common variances among the types of war events were adjusted for to yield independent associations with psychotic symptoms. Multiple linear regression models were fitted using the criteria outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986) to assess the proposed mediation. All variables were standardized to a mean of zero and standard deviation (SD) of 1 (Z scores) to ensure comparability in the mediation model. To assess for mediation, we first quantified the relationships between exposure to war experiences and psychotic symptoms, exposure to war experiences and post-war hardships, and post-war hardships and psychotic symptoms adjusted for exposure to war experiences. Next, we assessed mediation by determining the degree of attenuation in the relationship between general war experiences and psychotic symptoms when including post-war hardships in the model. The attenuation was scaled as the relative decrease in the regression coefficient for general exposure to war experiences. We applied bootstrapping methods to obtain 95% confidence limits (95% confidence intervals [CIs]) for the mediated effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). CI based on bias-corrected bootstrapping have been shown to be the most accurate method of assessing mediated effects (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). All analyses were conducted using Stata OCLA version 12.

Ethical considerations

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Gulu University approved the WAYS study. Gulu University IRB is an affiliate of the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST), a body that oversees research in Uganda. Subsequently, written informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with ethical guidelines and approvals. No financial incentives were given, but participants received a T-shirt each in appreciation for their time and participation after the interview sessions. The WAYS study employed a clinical psychiatric officer to make referrals to the regional referral hospital in case of a mental health emergency such as severe depression, suicidality, or conduct problems with potential for harm. Referral took place in instances where there was a potential for harm such as suicide, homicide, and major depression. There are numerous mechanisms of support systems initiated by NGOs such as religious leaders, elders, local leaders, and community social workers, all trained by NGOs as lay counsellors to provide psychological support to war-affected people in the communities.

Although the potential for stigmatization and discrimination was ever present, especially against former child soldiers who were known to have committed acts of aggression against their own communities, sections of the population empathized with the children concerned, arguing that the children were forced to act violently towards their own communities against their will. It is possible that these acts of compassion protected some child soldiers against stigma and discrimination. Also, some time had elapsed since the end of the war (Ovuga et al., 2012).

Results

The characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. The sample consisted of 539 war-affected youths (male = 329, 61%). In general, the mean age at baseline was 22.39 years, SD = 2.03; minimum–maximum (min–max) = 18–25, mean age at abduction was 14.14 years, SD = 4.21, min–max = 7–22, and mean duration of captivity was 3.13 years, SD = 2.99, range = 0.5–17.75 years. Most of the war-affected youths were abducted between 11 and 15 years of age. Descriptive statistics (mean, SD, range) and correlations between variables in the study were computed and are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and bivariate correlation among variables in the study.

| Variables | Mean | SD | Minimum–maximum | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sex (male: n, %) | 329, 69 | 1 | ||||||

| 2 | Age at baseline | 22.39 | 2.03 | 18–25 | .07 ns | 1 | |||

| 3 | Psychotic symptoms | 3.98 | 2.64 | 00–12 | .08 | −.08 | 1 | ||

| 4 | Post-war hardships | 12.47 | 4.99 | 00–24 | −.06 ns | −.01 | .42*** | 1 | |

| 5 | General war experiences | 41.71 | 4.19 | 00–52 | −.07 ns | .05 | .37*** | .63*** | 1 |

SD: standard deviation; Min: minimum; Max: maximum; ns: not significant.

Significant statistics are in bold.

p < .001.

Psychotic symptoms correlated significantly with war experiences as well as post-war hardships. Likewise, war experiences significantly correlated with post-war hardships. Age and sex were not significantly correlated with any of the variables in our preliminary analyses, and they were removed from subsequent analyses.

Table 2 shows different types of war experiences regressed on psychotic symptoms each at a time in separate univariable regression models. Of the experiences assessed, ‘witnessing violence’, ‘direct personal harm’, ‘threat to self’, ‘deaths’, ‘threat to loved ones’, ‘involvement in hostilities’, ‘sexual abuse’, and ‘general number of war experiences’ significantly predicted psychotic symptoms. The proportion of explained variance for the models for univariable analyses is included and was in the range of R2 = .02, F(1, 537) = 81.32, p < .001, for ‘involvement in hostilities’ to R2 = .15, F(1, 537) = 78.58, p < .001, for ‘total number of war experiences’ (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariable regression analyses of different types of war experiences on psychotic symptoms.

| S/no. | Types of war experiences | β | SE | 95% CI | R 2 | F-ratio | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Witnessing violence | .21 | 0.04 | 0.13 to 0.29 | R2 = .05 | F(1, 537) = 23.95 | p < .001 |

| 2 | Direct personal harm | .18 | 0.04 | 0.10 to 0.27 | R2 = .04 | F(1, 537) =18.27 | p < .001 |

| 3 | Threat to self | .16 | 0.04 | 0.08 to 0.25 | R2 = .03 | F(1, 537) =14.62 | p < .001 |

| 4 | Deaths | .18 | 0.04 | 0.09 to .26 | R2 = .05 | F(1, 537) =16.99 | p < .001 |

| 5 | Harm to loved ones | .04 | 0.05 | 0.04 to 0.13 | R2 = .00 | F(1, 537) = 0.77 | ns |

| 6 | Material losses | .06 | 0.04 | 0.02 to 0.14 | R2 = .001 | F(1, 537) =1.96 | ns |

| 7 | Threat to loved ones | .16 | 0.04 | 0.08 to 0.25 | R2 = .03 | F(1, 537) =14.62 | p < .001 |

| 8 | Displacement | .04 | 0.04 | 0.04 to 0.13 | R2 = .000 | F(1, 537) = 0.85 | ns |

| 9 | Involvement in hostilities | .14 | 0.04 | 0.06 to 0.23 | R2 = .02 | F(1, 537) =11.15 | p < .001 |

| 10 | Separation | .07 | 0.04 | 0.01 to 0.16 | R2 = .001 | F(1, 537) = 3.01 | ns |

| 11 | Sexual abuse | .19 | 0.04 | 0.11 to 0.28 | R2 = .04 | F(1, 537) =19.64 | p < .001 |

| 12 | General war experiences | .38 | 0.04 | 0.29 to 0.46 | R2 = .15 | F(1, 537) = 78.58 | p < .001 |

R2: adjusted R-squared; SE: standard errors; CI: confidence interval; ns: not significant.

To examine their independent contributions to psychotic symptoms, all the types of war experiences that significantly predicted psychotic symptoms in the univariable models except ‘exposure to general war experiences’ were entered in one multivariable regression model simultaneously. ‘Witnessing violence’, ‘deaths’, ‘involvement in hostilities’, and ‘sexual abuse’ independently and significantly predicted psychotic symptoms (Table 3). The proportion of explained variance for the multivariable model was R2 = .09, F(7, 531) = 7.90, p < .001.

Table 3.

Multivariable regression analyses of different types of war experiences on psychotic symptoms in one model.

| S/no. | Categories of war experiences | β | SE | 95% CI | R 2 | F-ratio | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Witnessing violence | .12 | 0.04 | 0.02 to 0.21 | R2 = .09 | F(7, 531) = 7.90 | p < .001 |

| 2 | Deaths | .11 | 0.04 | 0.02 to 0.17 | |||

| 3 | Involvement in hostilities | .10 | 0.05 | 0.01 to 0.19 | |||

| 4 | Sexual abuse | .14 | 0.04 | 0.03 to 0.20 |

R2: adjusted R-squared; SE: standard error; CI: confidence interval.

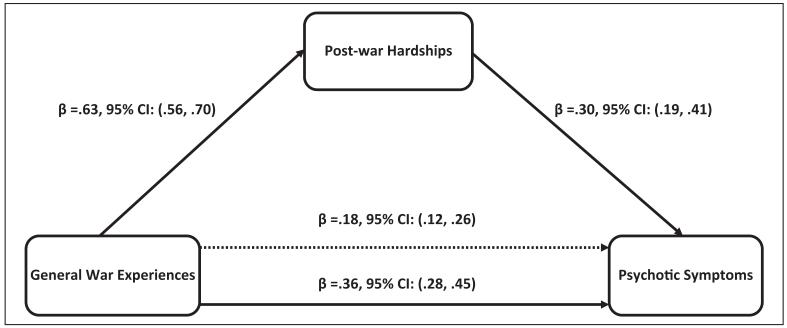

In evaluating the strength of the direct relationships, there were significant direct associations between the general war experiences and psychotic symptoms (Figure 1). Post-war hardships were significantly associated with general exposure to war experiences and with psychotic symptoms (Figure 1). Post-war hardships mediated the relationship between war experiences and psychotic symptoms by statistically significant indirect paths between war experiences and psychotic symptoms (β = .18, 95% CI = [0.12, 0.26]). Approximately 50% of the effect of war experiences on psychotic symptoms is mediated through post-war hardships. The effects of war experiences on psychotic symptoms reduced but remained statistically significant after including post-war hardships (β = 0.18, 95% CI = [0.12, 0.28]) indicating partial mediation. The proportion of explained variance for the model with only war experiences was R2 = .15, F(1, 537) = 78.58, p < .001, but this increased to R2 = .19, F(2, 536) = 49.96, p < .001, when post-war hardships were included in the mediation model.

Figure 1.

Mediation by post-war hardships of the relations between general war experiences and psychotic symptoms.

The coefficient immediately above the continuous line is before the mediator and was added to the model, and the one above the dotted line is after the mediator and was added to the model.

Indirect effect: (mediated effect) = β = .18, confidence interval (CI) = [0.10, 0.25].

Proportion of total effect = 0.18/0.36 = 0.50 (or 50%).

Ratio of indirect to direct effect = 0.18/0.18 = 1.0.

Ratio of total to direct effect = 0.36/0.18 = 2.0.

Bootstrap results =β = 0.77, CI = [0.72, 0.82].

Discussion

Using data from an ongoing longitudinal study of former child abductees, this study sought to evaluate the contributions of various types of previous war experiences on psychotic symptoms. In addition, the study assessed the mediating role of post-war hardships on the relations between general exposure to war experiences and psychotic symptoms among former child soldiers more than 6 years following the end of the war in Northern Uganda. In separate univariable models, we found ‘witnessing violence’, ‘direct personal harm’, ‘threat to self’, ‘deaths’, ‘threat to loved ones’, ‘involvement in hostilities’, ‘sexual abuse’, and ‘general exposure to war experiences’ as types of war experiences that significantly predicted psychotic symptoms. When all types of war experiences (excluding ‘general exposure to war experiences’) were assessed simultaneously in a multivariable analyses, only ‘witnessing violence’, ‘deaths’, ‘involvement in hostilities’, and ‘sexual abuse’ emerged as significant and independent predictors of psychotic symptoms. Finally, post-war hardships accounted for 50% of the association between war experiences and psychotic symptoms indicating that the enduring effect of war experiences on symptoms of psychosis in former child soldiers could be through post-war hardships. However, despite this significant reduction in the effects of war experiences on psychotic symptoms, the direct effects of war experiences on psychotic symptoms remained statistically significant suggesting that other proximal risk factors beyond post-war hardships account for the remaining 50%.

The finding in this study is supported by previous studies in which the atrocities perpetrated during the war might explain the continued toxic effect of ‘witnessing violence’, ‘direct personal harm’, ‘threat to self’, ‘deaths’, ‘threat to loved ones’, ‘involvement in hostilities’, and ‘sexual abuse’ on psychotic symptoms in former child soldiers. Indeed, war exposure such as involvement in combat has previously been suggested to relate to psychotic symptoms (Kelleher, Keeley, & Corcoran, 2013; Kinzie & Boehnlein, 1989). Furthermore, while in captivity the former child soldiers were tortured, witnessed atrocities, were threatened with death, and they were told that their relatives would be killed too. Indeed, this happened to some of those who attempted to escape and succeeded in their escape from rebel captivity (Amone-P’Olak, 2009; Angucia, 2010; Derluyn et al., 2004; Ehrenreich, 1997; Okello, Onen, & Musisi, 2007). This might explain why ‘threat to loved ones’ significantly predicted psychotic symptoms. The former child soldiers were also involved in combat where they were used as human shields during battles with government forces (Amone-P’Olak, 2009; Derluyn et al., 2004). Additionally, sexual abuse and exploitation was widely used in this war where young girls were specifically targeted for abduction to provide sexual services in captivity (Amone-P’Olak, 2005; Angucia, 2010; Okello, Onen, & Musisi, 2007; Ovuga et al., 2008).

The finding that 50% of the effects of war experiences on psychotic symptoms were mediated by post-war hardships is logical. The aftermath of war is fraught with numerous hardships and difficulties such as poverty, social exclusion, disempowerment, poor accommodation and sanitation. Similarly, domestic, gender-based, and community violence coupled with changes in family structure and functioning, lack of social support, and discrimination/stigma, are common in post-war environments (Amone-P’Olak, Stochl, et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2008; Miller & Rasmussen, 2010). All these hardships and difficulties may be linked to mental health difficulties such as PTSD, drug and substance abuse, all of which are risk factors for psychotic symptoms (Bayer et al., 2007; Ezard et al., 2011; Kelleher et al., 2013; Kinzie & Boehnlein, 1989). Nevertheless, the extent of mediation by post-war hardships in this study (accounting for 50% of the relationships) points to the presence of other proximal risk factors that may mediate the relations between war experiences and psychotic symptoms. Possible proximal risk factors among former child soldiers may include biological factors (e.g., genetic factors) or personality factors. These factors are outside the scope of this study and will be considered in subsequent studies.

The strength of this study lies in a relatively larger sample than in similar previous studies (Betancourt, Brennan, et al., 2010). Second, the instruments used were modified and validated in similar war-affected populations (Betancourt et al., 2009; UNICEF, 2010). Finally, the findings were not influenced by an ongoing war unlike previous studies (Amone-P’Olak et al., 2007; Angucia, 2010).

Nonetheless, some limitations need to be discussed as well. First, the items that denote psychotic symptoms in this study cannot be defined in terms of a clinical diagnosis, although the symptoms may be suggestive of a psychotic process. Second, there is a possibility of bias regarding the meaning of psychotic symptoms as employed in the study, and participants’ culture and understanding of the notion of psychotic symptoms. It is possible that the notion of psychotic symptoms may be confused with flashbacks and intrusive memories. This might have affected reporting rates and the validity of the instrument. In the local culture, it is believed that the spirit of the deceased might talk or appear to those who might have caused their deaths (Opiyo & Ovuga, 2014). Third, the cross-sectional design used in the study limits causal inferences. Fourth, there was no information regarding a prior history of psychotic symptoms in participants preceding the war. It is possible that psychotic symptoms may also cause post-war hardships, that is, some youth may have had early onset or pre-existing psychoses that made them even more vulnerable to post-war hardships. Nevertheless, in this study, we controlled for previous individual and family history of mental illness. It is therefore unlikely that previous mental health problems explain the results. Finally, it is possible that coding war experiences as present or absent might have masked the severity of war experiences. However, people with mental health problems are known to over-report the number and severity of stressful life events (Grant et al. 2006). Coding war experiences as present or absent was aimed at minimizing this potential for recall bias; thus, we used the number (count) of war experiences and not their perceived severity in our analyses. However, it is highly unlikely that these limitations affected the findings in any substantial way.

The results of this study have implications for research, policy, and practice. Research efforts should be directed at unravelling factors that may help to illuminate the path from war experiences to mental health problems such as psychotic symptoms. For policy makers and practising health workers, interventions should be directed towards reducing the adverse effects of war experiences such as witnessing violence, injuries resulting from war, deaths and bereavements, sexual abuse, as well as tackling post-war hardships.

Conclusion

Witnessing violence, deaths, involvement in hostilities, and sexual abuse independently predicted psychotic symptoms. These types of war experiences should therefore be considered when designing interventions to alleviate the effects of war experiences on psychotic symptoms in former child soldiers in humanitarian emergency settings. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that post-war hardships and difficulties are important determinants of psychotic symptoms reported by former child soldiers. Notwithstanding, other proximal risk factors beyond post-war hardships and difficulties such as guilt, PTSD, etc. appear to contribute to individual differences in experiencing psychotic symptoms in former child soldiers. Consequently, interventions to alleviate the adverse effects of war experiences and continuing post-war negative life events on psychotic symptoms should consider other factors such as psychological treatment to complement interventions aimed at reducing post-war hardships in former child soldiers and other war-affected populations who continue to experience psychotic symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded by The Wellcome Trust (Grant no. 087540/Z/08/Z) as part of the African Institutional Initiative for the project Training Health Researchers in Vocational Excellence (THRiVE) in East Africa.

References

- Al-Krenawi A, Lev-Wiesel R, Sehwail M. Psychological symptomatology among Palestinian children living with political violence. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2007;12:27–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2006.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amone-P’Olak K. A study of the psychological state of former abducted children at Gulu World Vision Trauma Centre. Torture. 2004;14:24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Amone-P’Olak K. Psychological impact of war and sexual abuse among adolescent girls in Northern Uganda. Intervention. 2005;3:33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Amone-P’Olak K. Coping with life in rebel captivity and the challenge of reintegrating formerly abducted boys in Northern Uganda. Journal of Refugee Studies. 2007;20:641–661. DOI:10.1093/jrs/fem036. [Google Scholar]

- Amone-P’Olak K. Torture against children in rebel captivity in Northern Uganda: Physical and psychological effects and implications for clinical practice. Torture. 2009;19:102–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amone-P’Olak K, Garnefski N, Kraaij V. Adolescents caught between fires: Cognitive emotion regulation in response to war experiences in Northern Uganda. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:655–669. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amone-P’Olak K, Jones PB, Abbott R, Meiser-Stedman R, Ovuga E, Croudace TJ. Cohort profile: Mental health following extreme trauma in a Northern Ugandan cohort of War-Affected Youth Study (The WAYS Study) SpringerPlus. 2013;2 doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-300. Article 300. DOI:10.1186/2193-1801-2-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amone-P’Olak K, Jones PB, Meiser-Stedman R, Abbott R, Ayella-Ataro PS, Amone J, Ovuga E. War experiences, general functioning and barriers to care among former child soldiers in Northern Uganda: The WAYS study. Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdt126. in press. Advance online publication. DOI:10.1093/pubmed/fdt126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amone-P’Olak K, Stochl J, Ovuga E, Abbott R, Meiser-Stedman R, Croudace TJ, Jones PB. Post-war environment and long-term mental health problems in former child soldiers in Northern Uganda: The WAYS study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2014;68:425–430. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203042. DOI:10.1136/jech-2013-203042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS. Social stress: Theory and research. Annual Review of Sociology. 1992;18:15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC. The sociology of mental health: Surveying the field. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, editors. Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Springer; New York, NY: 1999. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Angucia M. Broken citizenship: Formerly abducted children and their social reintegration in northern Uganda (Doctoral dissertation) University of Groningen; The Netherlands: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer CP, Klasen F, Adam H. Association of trauma and PTSD symptoms with openness to reconciliation and feelings of revenge among former Ugandan and Congolese child soldiers. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298:555–559. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Agnew-Blais J, Gilman SE, Williams DR, Ellis BH. Past horrors, present struggles: The role of stigma in the association between war experiences and psychosocial adjustment among former child soldiers in Sierra Leone. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Bass J, Borisova I, Neugebauer R, Speelman L, Onyango G, Bolton P. Accessing local instrument validity and reliability: A field-based example from Northern Uganda. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44:685–692. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0475-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Borisova I, Williams TP, Meyers-Ohki SE, Rubin-Smith JE, Annan J, Kohrt BA. Research review: Psychosocial adjustment and mental health in former child soldiers – A systematic review of the literature and recommendations for future research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:17–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02620.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Brennan RT, Rubin-Smith J, Fitzmaurice GM, Gilman SE. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: A longitudinal study of risk, protective factors, and mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:606–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhui K, Abdisalama A, Abdi M, Pereira S, Dualeh M, Robertson D, Ismail H. Traumatic events, migration characteristics and psychiatric symptoms among Somali refugees. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2003;38:35–43. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0596-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers . Child soldiers: Global report. Author; London, England: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coentre P, Power P. A diagnostic dilemma between psychosis and post-traumatic stress disorder: A case report and review of the literature. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2011;5 doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-97. Article 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derluyn I, Broekaert E, Schuyten G, De Temmerman E. Post-traumatic stress in former Ugandan child soldiers. Lancet. 2004;363:861–863. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15734-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich R. The scars of death: Children abducted by the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda. Human Rights Watch; New York, NY: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich R. The stories we must tell: Ugandan children and the atrocities of the Lord’s Resistance Army. Africa Today. 1998;45:79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ezard N, Oppenheimer E, Burton A, Schilperoord M, Macdonald D, Adelekan M, van Ommeren M. Six rapid assessments of alcohol and other substance use in populations displaced by conflict. Conflict and Health. 2011;5 doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-5-1. Article 1. DOI:10.1186/1752-1505-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando G, Miller KE, Berger D. The impact of potentially traumatic and daily stressors on emotional and psychosocial functioning and development of children in Sri Lanka: Disasters and their impact on child development [Special issue] Child Development. 2010;81:1192–1210. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garety PA, Kuipers E, Fowler D, Freeman D, Bebbington PE. A cognitive model of the positive symptoms of psychosis. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31:189–195. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003312. DOI:10.1017/S0033291701003312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Gipson PY, Campbell AJ, Westerholm RI. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Evidence Of moderating and mediating effects. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:257–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher I, Keeley H, Corcoran P. Childhood trauma and psychosis in a prospective cohort study: Cause, effect, and directionality. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170:734–741. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12091169. DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12091169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzie J, Boehnlein J. Post-traumatic psychosis among Cambodian refugees. Journal of Trauma Stress. 1989;2:185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Machel G. The impact of war on children. Hurst & Company; London, England: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Omidian P, Rasmussen A, Yaqubi A, Daudzai H. Daily stressors, war experiences, and mental health in Afghanistan. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2008;45:611–639. doi: 10.1177/1363461508100785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Rasmussen A. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenwald M, Neuner F, Schauer M, Elbert T, Catani C, Lingenfelder B, Rockstroh B. Khat use as risk factor for psychotic disorders: A cross-sectional and case-control study in Somalia. BMC Medicine. 2005;3 doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-3-5. Article 5. DOI:10.1186/1741-7015-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okello J, Onen T, Musisi S. Psychiatric disorders among war-abducted and non-abducted adolescents in Gulu district, Uganda: A comparative study. African Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;20:225–231. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v10i4.30260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opiyo EA, Ovuga E. Chapter 12: Peace building rituals in Acholi culture. In: Ovuga E, Obika JA, Olido K, Opiyo EA, editors. Conflict and peace studies in Africa: Peace and peace building: Enhancing human security. Vision Printing; Kampala, Uganda: 2014. pp. 304–312. [Google Scholar]

- Ovuga E, Opiyo EA, Obika JA, Olido K. Conflict and Peace Studies in Africa: Peace and Peace Building: Concepts and perceptions in Northern Uganda. Vision Printing; Kampala: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ovuga E, Oyok T, Moro EB. Posttraumatic stress disorder among former child soldiers attending a rehabilitative service and primary school education in Northern Uganda. African Health Sciences. 2008;8:136–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and re-sampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert F. Guerrillas don’t die easily: Everyday life in wartime and the guerrilla myth in the National Resistance Army in Uganda, 1981-1986. International Review of Social History. 2006;51:93–111. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . Northern Uganda psychosocial needs assessment report (NUPSA) Marianum Press; Kisubi, Uganda: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . UNICEF B&H Post-war Screening Survey. Author; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]