Abstract

Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis (CP) is a very rare but serious form of central nervous system fungal infection that is caused by dematiaceous fungi. It is commonly associated with poor prognosis irrespective of the immune status of the patient. In this study, the authors describe the first case of CP in Korea that occurred in a 75-year-old man without immunodeficiency and showed favorable outcome after surgical excision and antifungal therapy. In addition, the authors herein review the literature regarding characteristics of this rare clinical entity with previously reported cases.

Keywords: Brain abscess, Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis, Fungal infection, Treatment

INTRODUCTION

Fungal brain abscesses are well known to be associated with the immunocompromised state. However, cerebral phaeohyphomycosis (CP) caused by darkly pigmented fungi appears to be a common exception to this rule because about one-half of this fungal infection occurred in patients with no underlying disease or risk factors. CP is a very rare cause of brain abscess, but is often a fatal disease regardless of immune status14,17,23).

The authors illustrate a 75-year-old, immunocompetent male patient who had a single brain abscess from dematiaceous fungi. To the authors' knowledge, this is the first case of CP in Korea.

CASE REPORT

A 75-year-old male, a resident of a rural area and a farmer by occupation, visited our outpatient clinic with the symptoms of poor cognition and memory decline over 2 weeks. He denied any history of fever, headache, blurred vision, vomiting or seizure. He was afebrile and his vital signs were stable. There were no laboratory abnormalities including leukocytosis or C-reactive protein rising. Upon the neurologic examination, he was conscious and there were no neurologic deficits except intermittent expressive dysphasia and disorientation. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed because of suspicion of some type of dementia. It showed a 20 mm sized nodular enhancing mass with peritumoral edema in the left frontal lobe. The mass had a central cystic portion with diffusion restriction (Fig. 1). High-grade glioma or metastatic tumor was initially presumed based on his age and progressive symptoms. Excisional biopsy was performed for tissue diagnosis. The lesion appeared to be white and took the form of a relatively hard mass with a clear boundary, permitting radical excision of the mass (Fig. 2). Pathological examination revealed multiple necrotizing granulomas with brown pigmented fungal hyphae. Septated hyphae and melanin pigments were confirmed at Fontana-Masson stain consistent with CP (Fig. 3).

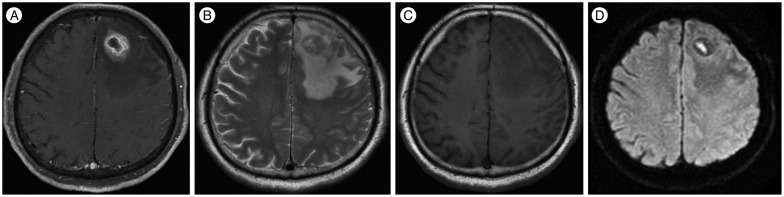

Fig. 1.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows heterogenous enhancing nodular lesion in left frontal lobe with adjacent edema (A). The mass is slightly hyperintense on T2-weighted image (B) and isointense on T1-weighted image (C). The cavity in central portion is brightly shown on diffusion-weighted image (D).

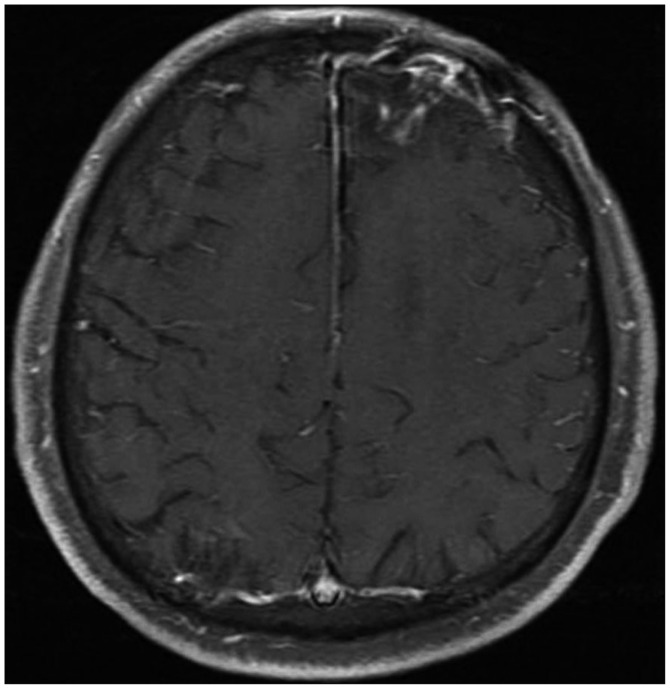

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative photography demonstrates a white-yellowish and hard mass with well-defined capsule.

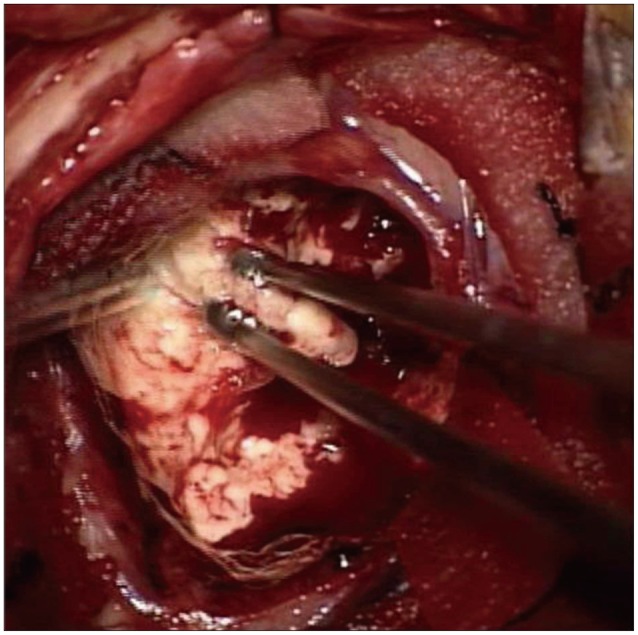

Fig. 3.

Gross preparation shows white, well-demarcated, round masses in brain parenchyma (A). Hematoxylin and eosin stain reveals necrotizing granulomas (red stared, ×100) and inflammatory infiltrates (yellow stared, ×100) (B), as well as brown colored septated hyphae (×1000) (C). Black colored melanin pigments are present in branched fungal hyphae on Fontana-Masson stain (×400) (D).

The patient was started on intravenous amphotericin B at a dose of 68 mg daily. After 10 days, he was switched to 270 mg of intravenous voriconazole twice a day because of the elevation of serum creatinine. He took the injection for 8 weeks, followed by oral voriconazole 200 mg twice a day for 2 months. A follow-up brain MRI 3 weeks after surgical excision demonstrated a significant resolution of the edema. Ongoing resolution of the lesion was found on the latest follow-up MRI (Fig. 4). He showed dramatic improvement in his symptoms including disorientation and memory disturbance after completion of surgery and antifungal therapy.

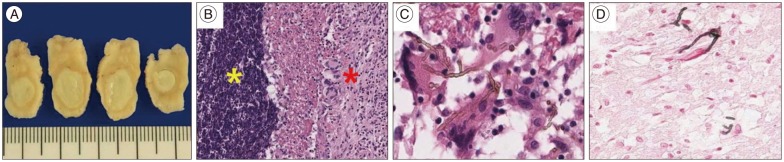

Fig. 4.

Magnetic resonance imaging 1 year after surgery depicts complete resolution of abscess and edema in the frontal lobe.

DISCUSSION

CP is a rare infection caused by darkly pigmented fungi, namely dematiaceous fungi23). Dematiaceous fungi represent a group of filamentous molds that contain melanin pigment in their cell walls3,6,14,17). Cladophialophora bantiana is the most frequently isolated species. Rhinocladiella mackenziei (formerly Ramichloridium mackenziei) is the second most common cause of CP, which is exclusively endemic in the Middle East area17,22). Most agents are found in soil. Because of this, occupational predisposition has been reported in agricultural workers, especially farmers due to risk of soil exposure17,23). CP commonly occurs in the second and third decades of life with male predominance, except Rhinocladiella mackenziei which affects adults with a median age of 62 years without male predominance3,13,23).

The most unique characteristic of CP is its occurrence irrelevant to the immune status of the host15,17,19,23). Even though immunodeficiency may play a role as a risk factor, there are many reports of this infection in immunocompetent individuals similar to the patient in this report12,15,17,19,25). The portal entry to brain is unclear, although several possible routes have been suggested, such as hematogenous dissemination of inhaled spores or accidental skin inoculation as well as direct extension from adjacent paranasal sinuses or ears2,6,10,14,15,19,22,23). The authors were unable to ascertain the route of infection in the present case. Pathogenesis of CP is associated with the presence of melanin as a virulence factor that provides advantages in evading host defense and crossing the blood-brain barrier by binding to hydrolytic enzyme14,16,17).

Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis was listed as a variable, ranging from solitary subcutaneous nodules to a life-threatening infection5,11,16,17,18). In the central nervous system (CNS) manifestation, brain abscess is a classic clinical presentation3,23). Patients can also present meningitis, encephalitis, myelitis or arachnoiditis17,19). Hemiparesis and headache are the most common symptoms followed by various clinical manifestations17). About 70-80% of cases typically manifest as a single brain abscess particularly on the frontal lobe (52%) like in our case, while multiple brain abscesses can be seen in immunocompromised patients3,6,17,19).

The diagnosis of CP can be difficult because dematiaceous fungi are often considered contaminants when identified in culture. Furthermore, the pathogen can not always be cultured and isolated from the serum or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)12,21,24). No molecular techniques are available to speedily identify these fungi even to the genus level17). Therefore, diagnosis is made by surgical biopsy. Only the tissue examination can be useful to identify irregularly swollen hyphae with yeast-like structure and to confirm the presence of dematiaceous hyphae in melanin-specific Fontana-Masson stain14,17). Unfortunately in this case, fungus was not identified in the culture of surgical specimen, therefore, the species that causes CP could not be detected. Meanwhile, the brain MRI reveals a ring-enhancing lesion with a low-attenuation core, suggesting the presence of necrosis or pus10,19). In cases where high-grade glioma or metastasis is mimicked by irregular and variably contrast-enhancing lesions, magnetic resonance spectroscopy may be used to differentiate the entities6,7,19). Imaging findings of this patient were more suggestive of a glioma than an abscess, because nodular heterogeneity on contrast injection mimicked the images seen in high-grade tumors. Consequently, surgical biopsy is essential for the diagnosis of CP.

Because of the rarity of the cases, there is no standard treatment guidelines for CP. A combination of surgical and medical treatments is generally recommended10,22). Complete excision of brain lesions may provide better results than simple aspiration unless the lesion is multiple or is located within the eloquent area of the brain3,17). Antifungal agents are generally used in combination of amphotericin B, 5-flucytosine and itraconazole because it is associated with improved survival rates3,14,17,20). Voriconazole can be used as alternative to itraconazole because of its good penetration into both CSF and brain tissue17,22). Duration of taking the medications is still unknown because most reported patients expired during treatment except a few survivors who received voriconazole for about 12 months8,19). In addition, posaconazole may be a potent drug when pathogen is Rhinocladiella mackenziei1,3,8). In this case, amphotericin B was replaced by voriconazole because of serum creatinine elevation. Amphotericin B has fatal side effects such as nephrotoxicity, therefore, close observation on kidney function is needed.

The prognosis of CP is poor. Mortality rate approaches 100% in untreated patients, while that of treated cases as high as 65% to 73% despite the aggressive treatment6,9,10,17,19,23). Interestingly, mortality rate did not differ significantly between immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients (75% vs. 71%)12,17). Multiple brain abscesses are associated with worse prognosis than solitary lesion4,23). Fortunately, the patient reported here had a good response to surgery and chemotherapy and showed fine recovery without any sequela. Solitary lesion and the good general condition of the patient, together with an aggressive therapeutic approach, are therefore inferred to contribute to a favorable outcome. Further studies are necessary to find more potentially useful antifungal regimen for these refractory infections and to investigate more detailed pathophysiology and prognostic factors to increase the survival rate.

CONCLUSION

CP is rare disease, but challenging one with high mortality rate, particularly when the CNS is affected. As shown in this report, complete resection and adequate antifungal therapy are the most recommended modality for patients with CP-related abscess to this time.

References

- 1.Badali H, de Hoog GS, Curfs-Breuker I, Meis JF. In vitro activities of antifungal drugs against Rhinocladiella mackenziei, an agent of fatal brain infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:175–177. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt ME, Warnock DW. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and therapy of infections caused by dematiaceous fungi. J Chemother. 2003;15(Suppl):36–47. doi: 10.1179/joc.2003.15.Supplement-2.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cristini A, Garcia-Hermoso D, Celard M, Albrand G, Lortholary O. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis caused by Rhinocladiella mackenziei in a woman native to Afghanistan. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3451–3454. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00924-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon DM, Walsh TJ, Merz WG, McGinnis MR. Infections due to Xylohypha bantiana (Cladosporium trichoides) Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:515–525. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fader RC, McGinnis MR. Infections caused by dematiaceous fungi : chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1988;2:925–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gongidi P, Sarkar D, Behling E, Brody J. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis in a patient with neurosarcoidosis on chronic steroid therapy secondary to recreational marijuana usage. Case Rep Radiol. 2013;2013:191375. doi: 10.1155/2013/191375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauck EF, McGinnis M, Nauta HJ. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis mimics high-grade astrocytoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:1061–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jabeen K, Farooqi J, Zafar A, Jamil B, Mahmood SF, Ali F, et al. Rhinocladiella mackenziei as an emerging cause of cerebral phaeohyphomycosis in Pakistan : a case series. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:213–217. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kantarcioglu AS, de Hoog GS. Infections of the central nervous system by melanized fungi : a review of cases presented between 1999 and 2004. Mycoses. 2004;47:4–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2003.00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li DM, de Hoog GS. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis--a cure at what lengths? Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:376–383. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsumoto T, Ajello L, Matsuda T, Szaniszlo PJ, Walsh TJ. Developments in hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32(Suppl):329–349. doi: 10.1080/02681219480000951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ochiai H, Kawano H, Minato S, Yoneyama T, Shimao Y. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis : case report. Neuropathology. 2012;32:202–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2011.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palaoglu S, Sav A, Basak T, Yalcinlar Y, Scheithauer BW. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:894–897. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199311000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ravisankar S, Chander RV. Cerebral pheohyphomycosis : report of a rare case with review of literature. Neurol India. 2013;61:526–528. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.121936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Revankar SG. Dematiaceous fungi. Mycoses. 2007;50:91–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, Pullen R, Rinaldi MG. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis : review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467–476. doi: 10.1086/338636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revankar SG, Sutton DA, Rinaldi MG. Primary central nervous system phaeohyphomycosis : a review of 101 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:206–216. doi: 10.1086/380635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rinaldi MG. Phaeohyphomycosis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:147–153. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosow L, Jiang JX, Deuel T, Lechpammer M, Zamani AA, Milner DA, et al. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis caused by Bipolaris spicifera after heart transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2011;13:419–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharkey PK, Graybill JR, Rinaldi MG, Stevens DA, Tucker RM, Peterie JD, et al. Itraconazole treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(3 Pt 2):577–586. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70259-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimosaka S, Waga S. Cerebral chromoblastomycosis complicated by meningitis and multiple fungal aneurysms after resection of a granuloma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1983;59:158–161. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.59.1.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sood S, Vaid VK, Sharma M, Bhartiya H. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis by Exophiala dermatitidis. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2014;32:188–190. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.129830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suri P, Chhina DK, Kaushal V, Kaushal RK, Singh J. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis due to cladophialophora bantiana - a case report and review of literature from India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:DD01–DD05. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7444.4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takei H, Goodman JC, Powell SZ. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis caused by ladophialophora bantiana and Fonsecaea monophora : report of three cases. Clin Neuropathol. 2007;26:21–27. doi: 10.5414/npp26021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watson KC. Cerebral chromoblastomycosis. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1962;84:233–237. doi: 10.1002/path.1700840128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]