Abstract

Introduction

Sepsis is the leading cause of mortality in non-cardiological critically ill patients. There are as many as 20 million cases of sepsis annually worldwide, with a mortality rate of around 35%. It has been reported that the dysregulation of haemostatic system due to the interaction between coagulation system and inflammatory response is a strong predictor of mortality in patients with severe sepsis. In this context, several anticoagulants have been evaluated in recent years. However, the results of these studies were inconsistent and even contradictory. In addition, there is insufficient evidence comparing the efficacy and safety of different anticoagulants. The purpose of our study is to carry out a systematic review and network meta-analysis comparing the efficacy and safety of different anticoagulants for severe sepsis based on existing randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and ranking these anticoagulants for practical consideration.

Methods and analysis

PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Library databases will be systematically searched for eligible studies. Randomised controlled trials (RCT) on anticoagulant therapy for severe sepsis with multiple outcome measures will be included. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool will be used to assess the quality of included studies. The primary outcomes are mortality and bleeding events. The secondary outcomes include the length of intensive care stay, the length of hospital stay and duration of mechanical ventilation. Direct pairwise meta-analysis (DMA), indirect treatment comparison meta-analysis (ITC) and network meta-analysis (NMA) will be conducted to compare different anticoagulants.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required given that this is a protocol for a systematic review. The protocol of this systematic review will be disseminated in a peer-reviewed journal and presented at a relevant conference.

Trial registration number

This protocol has been registered in PROSPERO (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/) under registration number CRD42014013886.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first comprehensive review comparing the efficacy and safety of five different anticoagulants through network meta-analysis.

The results of this systematic review will help clinicians in making decisions in clinical practice.

The methods of this review are state of the art, including extensive literature search, explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria, independent study selection, data extraction, quality assessment and advanced statistical methods. In addition, we will use the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to evaluate the quality of evidence.

This study is inherently retrospective and based on the published randomised controlled trials only.

Introduction

Sepsis has been reported as the leading cause of mortality in non-cardiological critically ill patients.1 In the USA, nearly 200 000 deaths are attributed to sepsis per year2 and it is likely that there are as many as 20 million cases of sepsis annually worldwide, with a mortality rate of around 35%.3 Sepsis, defined as infection-induced systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) involves multiple mechanisms, including the release of cytokines, the activation of complement systems, coagulation systems and fibrinolytic systems.4 Of these, the dysregulation of haemostatic system from insignificant coagulopathy to severe disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) has been shown to be related with the development of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS).5–7 In a prospective epidemiological study, the authors found that the prevalence of DIC, MODS and the risk of death were associated with the severity of the disease; the more severe the infection (from SIRS to septic shock), the higher the risk of DIC, MODS and death.1 It has been reported that DIC can be found in 25–50% of patients with sepsis.8 9 Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that use of anticoagulants to inhibit the over-activated coagulation cascade may be useful in the resolution of DIC and reducing the mortality from sepsis. Following this hypothesis, the efficacy and safety of several anticoagulants were evaluated in many RCTs and meta-analysis. However, the results of these studies were inconsistent and were even contradictory.10 As a result, considerable differences exist between guidelines in the areas of treatment of DIC. The guideline published by UK recommended the use of recombination-activated protein C (rAPC) for serious cases; however, the guideline published by Japan recommended the use of supplement dose of antithrombin.10 Moreover, in majority of these studies, the target drugs were often compared with placebo; therefore, there is no evidence of which one is better.

The purpose of our study is to carry out a systematic review and network meta-analysis comparing the efficacy and safety of different anticoagulants for severe sepsis based on existing RCTs and ranking these anticoagulants for practical consideration. This study is expected to begin in August 2014 and conclude in November 2015.

Methods and analysis

Design

Systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis will be reported according to the recommendations from the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA, http://www.prisma-statement.org/).

Data sources and searches

We will systematically perform an electronic search of PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Library. In addition, we will also search conference abstracts from the Society of Critical Care Medicine, the European Society for Intensive Care Medicine, the American Thoracic Society and the American College of Chest Physicians, as well as the Clinicaltrials.gov and Controlled-trials.com along with the bibliographies of eligible studies and relevant review articles or meta-analysis. The following medical subject heading terms and text words will be used alone or in combination: SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis, severe sepsis, septic shock, pyemia*, pyohemia*, pyaemia*, septicemia*, bacteremia, anticoagulant*, anticoagulation therapy, heparin, antithrombin, drotrecogin alfa (activated), activated protein C, xigris, rAPC, rhAPC, recombinant thrombomodulin, recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin, rTM, rhTM, ART, tissue factor pathway inhibitor, TFPI, Tifacogin, random controlled trial and RCT. No limitation will be placed on publication status or language.

Eligibility criteria

Participants: Inclusion—adult patients (>18 years) with sepsis of any severity, defined according to the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP)/Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) definition or ACCP/SCCM/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine/American Thoracic Society/Surgical Infection Society definition.11 12 Patients with sepsis induced DIC should fulfil the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) DIC score or the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (JAAM) DIC scoring system.13

Interventions: Inclusion—any RCT that evaluates the efficacy and safety of five anticoagulants including heparin, antithrombin, rAPC, rhTM and TFPI (of any dose).

Controls: Inclusion—any RCT that evaluates the efficacy and safety of five anticoagulants including heparin, antithrombin, rAPC, rhTM and TFPI (of any dose) and placebo or other standard therapy according to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (http://www.survivingsepsis.org/Resources/Pages/default.aspx).

Outcome: Inclusion—the primary outcome of this study is mortality with the longest follow-up period and bleeding events during therapy process (including minor and major bleeding events; the definitions of minor and major bleeding events are developed by individual studies). The secondary outcomes include the length of intensive care stay, the length of hospital stay and duration of mechanical ventilation. In addition, we will also evaluate the difference of acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II scores, sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scores and DIC scores between two groups.

Types of study: Inclusion—only RCTs will be included.

Exclusion criteria—age less than 18 years, patients with non-infectious SIRS, studies that evaluate other drugs or combined treatments with multiple drugs; there are no original data (eg, case reports, reviews and commentary), experimental studies and observational studies.

Study selection

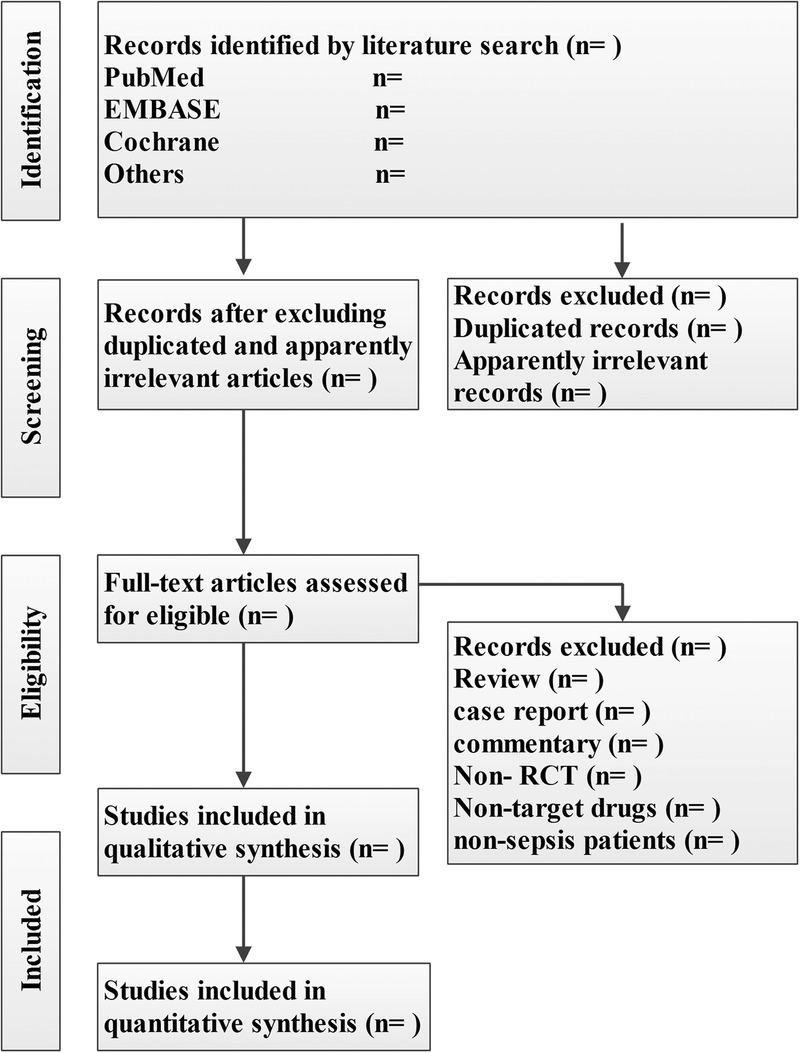

The titles and abstracts of literature search will be screened by two reviewers independently for potentially relevant studies according to the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. After excluding the duplicated and apparently irrelevant studies, the remaining studies will be read in full text. Any disagreement will be resolved by consensus. The primary selection process is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

The primary selection process.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The following data will be extracted independently and in duplicate by two reviewers into a predefined spreadsheet: the name of the first author, publication year, country of origin, patient’s characteristics (gender, age, number, inclusion and exclusion criteria, APACHE II scores, SOFA scores and DIC scores), characteristics of interventions (type and dose of target drug), characteristics of control treatment, outcomes (mortality at different time points, bleeding events, the length of intensive care stay, the length of hospital stay and duration of mechanical ventilation). Any discrepancy will be resolved by consensus. If necessary, we will try to contact the corresponding authors for more information.

The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool will be adopted to assess the risk of bias for each RCT by two reviewers.14 This tool includes six domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete data assessment, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias. Based on the above domains, the included RCTs will be classified into three categories: low risk, high risk and unclear. Any discrepancy will be resolved by consensus and discussion.

Assessment of reporting biases

A funnel scatter plot of sample and effect size will be constructed to determine the presence of publication bias and the contour-enhanced funnel plot will be applied to aid in interpreting the funnel scatter plot. If studies are missing in areas of low statistical significance, the asymmetry may be due to publication bias. If studies are missing in areas of high-statistical significance, the asymmetry may be due to other factors. Begg-Mazumdar rank correlation and Egger's regression will be used to assess small trial bias statistically.15–17

Data synthesis

Direct pairwise meta-analysis (DMA) will be conducted by Review Manager V.5.3 (http://tech.cochrane.org/revman). We will calculate risk ratio (RR) with its 95% CIs for dichotomous data and mean differences (MD) with its 95% CIs for continuous data. Weighted mean differences will be used for data measured on the same scale and for which the same units are used; otherwise, standardised mean differences will be used (http://www.cochrane.org/handbook). Heterogeneity will be quantified with Q-statistic and I2 index; p<0.1 or I2 >50% indicates the presence of at least moderate heterogeneity and in this case, the random-effect model will be used. Otherwise, the fixed-effect model will be used. I2 will be calculated according to the equation I2=100%×(Q−df)/Q, where Q is the Cochran heterogeneity statistic.18 19

When lacking head-to head evidence, indirect treatment comparison meta-analysis (ITC) will be retrieved from available evidence by using ITC software (http://www.cadth.ca/en/resources/about-this-guide/chapter-2-using-the-itc-application) will be used to obtain indirect data. In this meta-analysis, only indirect results between two comparisons, such as A vs B and B vs C, an indirect result (A vs C) will be calculated.

Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) is a technique to meta-analyse more than two drugs at the same time. In our study we will use a full Bayesian evidence network. NMA will be performed using ADDIS software (http://www.medfloss.org/node/812). We will estimate the ranking probability for each anticoagulant—the most efficacious, the second best, the highest bleeding incidence, the second highest bleeding incidence, etc—and present the results graphically. The data will also be expressed as RR or MD with 95% CI.

Consistency between direct and indirect evidence will be checked by a node splitting model through ADDIS software. When 95% CIs of inconsistency factors included zero or p>0.05, this indicates there is non-significant inconsistency between direct and indirect evidences.20 Meanwhile, Z test described by Song will be used to evaluate the difference between DMA or ITC and NMA effects. p<0.05 indicates there is significant difference between DMA or ITC and NMA effects.21

Subgroup analysis

Several subgroup analyses will be performed based on the length of the follow-up period (ICU mortality, hospital mortality, 28/30 days mortality and 90 days mortality), the severity of the disease (APACHE II≥25 or <25) and the incidence of DIC (yes or no).

Sensitivity analysis

We will assess the robustness of our results through a series of sensitivity analysis, that is, by excluding trials at high risk of bias, removing 1 study at a time iteratively, using ORs and risk differences as a measure of treatment effect and using both fixed and random effects models.

Quality of evidence

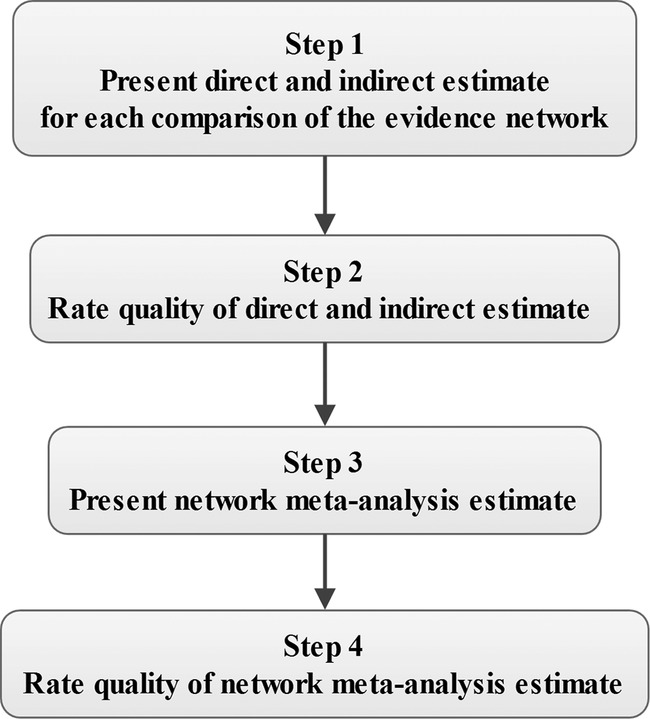

The quality of evidence will be assessed by GRADE four step approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from NMA; the process is shown in figure 2.22 The quality of evidence is classified by the GRADE group into four levels: high quality, moderate quality, low quality and very low quality. The quality rating of RCT may be rated down by −1 (serious concern) or −2 (very serious concern) for the following reasons: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias. This process will performed using GRADE pro 3.6 software (http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

Figure 2.

Approach for rating the quality of network meta-analysis (NMA) estimates.

Discussion

To our best knowledge, our study will be the first network meta-analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of different anticoagulants including heparin, antithrombin, rAPC, rhTM and TFPI. It is important for clinicians to utilise best evidence to guide the clinical practice. The dysregulation of haemostatic system, especially the incidence of DIC, is a strong predictor of mortality.23 Thus it should be diagnosed and treated early.24 25 In the past few decades, several anticoagulants have been extensively evaluated, however, the results of these studies are inconsistent. In 2001, a randomised, double blind and placebo-controlled multicentre phase 3 study (Recombinant Human Activated Protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis (PROWESS)) found that administration of rAPC (24 μg/kg/h over 96 h) to patients with sepsis was associated with a significant decrease in deaths.26 However, this mortality benefit was not observed in a subsequent larger study, the Prospective Recombinant Human Activated Protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock (PROWESS-SHOCK study).27 Ultimately the decision to withdraw rAPC was made voluntarily by the manufacturer. Whereas, in a subsequent observational study containing 15 022 participants, in which 1009 (8%) received rAPC treatment, Casserly et al28 demonstrated that treatment with rAPC could significantly improve the survival rate of patients with severe sepsis. Moreover, the mortality benefit was confirmed in a large meta-analysis and such effects could still be observed when the PROWESS-SHOCK data were added to the analysis.29 Regarding antithrombin, a large RCT (KeyberSept) found there was no significant effect of antithrombin on survival of patients with severe sepsis.30 However, a subsequent RCT and two observational studies all reported that antithrombin supplement therapy, a dose of 3000 IU/day, could improve survival rate and increase the recovery rate from DIC without any risk of bleeding in patients with DIC with sepsis.31–33 Regarding TFPI, in two RCTs, the authors found a trend toward reduction of the 28-day mortality with the administration of TFPI.34 35 However, this effect was not observed in the subsequent larger RCTs.36 rTM is a novel anticoagulant. In a phase 2b study, the authors found a trend towards reduction of the 28-day mortality with the administration of rTM; the 28-day mortality was 17.8% in the rTM group and 21.6% in the placebo group (p=0.273).37 Based on the above analysis, a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study to assess the safety and efficacy of rTM in patients with severe sepsis and coagulopathy is currently recruiting participants (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01598831?term=ART-123&rank=2). Finally, in a large meta-analysis including 17 studies, the authors demonstrated that heparin significantly decreased 28-day mortality in patients with sepsis without increasing the risk of bleeding. However, the methodological quality of studies included in this meta-analysis was poor.38

As outlined above, based on these inconsistent results, guidelines published by UN, Japan and Italy recommended different drugs for the treatment of severe sepsis-induced coagulopathy. Another concern is that, in most of the current studies, the target drugs are often compared with placebo. Therefore, we do not know which one is better in terms of efficacy and safety. The purpose of our study is to carry out a systematic review and network meta-analysis comparing the efficacy and safety of different anticoagulants for severe sepsis based on existing RCTs and ranking these anticoagulants for practical considerations.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: LJ and YM contributed to the conception of the study. The manuscript protocol was drafted by LJ, SJ and XF and was revised by YM and MZ. The search strategy was developed by all the authors and will be performed by LJ, XF and SJ who will also independently screen the potential studies, extract data from the included studies, assess the risk of bias and complete the data synthesis. MZ and YM will arbitrate in cases of disagreement and ensure the absence of errors. All authors approved the publication of the protocol. All the above authors are members of China Emergency and Critical Care Evidence-based Medicine Group (CECCEBMG).

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Rangel-Frausto MS, Pittet D, Costigan M et al. . The natural history of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). A prospective study. JAMA 1995;273:117–23. 10.1001/jama.1995.03520260039030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J et al. . Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 2001;29:1303–10. 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniels R. Surviving the first hours in sepsis: getting the basics right (an intensivist's perspective). J Antimicrob Chemother 2011;66(Suppl 2):ii11–23. 10.1093/jac/dkq515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeerleder S, Hack CE, Wuillemin WA. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in sepsis. Chest 2005;128:2864–75. 10.1378/chest.128.4.2864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bone RC. Toward a theory regarding the pathogenesis of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome: what we do and do not know about cytokine regulation. Crit Care Med 1996;24:163–72. 10.1097/00003246-199601000-00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hack CE. Tissue factor pathway of coagulation in sepsis. Crit Care Med 2000;28:S25–30. 10.1097/00003246-200009001-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caliezi C, Wuillemin WA, Zeerleder S et al. . C1-Esterase inhibitor: an anti-inflammatory agent and its potential use in the treatment of diseases other than hereditary angioedema. Pharmacol Rev 2000;52:91–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dempfle CE, Wurst M, Smolinski M et al. . Use of soluble fibrin antigen instead of D-dimer as fibrin-related marker may enhance the prognostic power of the ISTH overt DIC score. Thromb Haemost 2004;91:812–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhainaut JF, Yan SB, Joyce DE et al. . Treatment effects of drotrecogin alfa (activated) in patients with severe sepsis with or without overt disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Thromb Haemost 2004;2:1924–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iba T, Nagaoka I, Boulat M. The anticoagulant therapy for sepsis-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Res 2013;131:383–9. 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.[No authors listed]. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med 1992;20:864–74. 10.1097/00003246-199206000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC et al. . 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:530–8. 10.1007/s00134-003-1662-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gando S, Saitoh D, Ogura H et al. . A multicenter, prospective validation study of the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine disseminated intravascular coagulation scoring system in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care 2013;17:R111 10.1186/cc12783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic review of intervention version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org (accessed Sep 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR et al. . Contour-enhanced meta-analysis funnel plots help distinguish publication bias from other causes of asymmetry. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:991–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M et al. . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088–101. 10.2307/2533446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ et al. . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dias S, Welton NJ, Caldwell DM et al. . Checking consistency in mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. Stat Med 2010;29:932–44. 10.1002/sim.3767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song F, Xiong T, Parekh-Bhurke S et al. . Inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons of competing interventions: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 2011;343:d4909 10.1136/bmj.d4909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puhan MA, Schunemann HJ, Murad MH et al. . A GRADE Working Group approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network meta-analysis. BMJ 2014;349:g5630 10.1136/bmj.g5630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kidokoro A, Iba T, Fukunaga M et al. . Alterations in coagulation and fibrinolysis during sepsis. Shock 1996;5:223–8. 10.1097/00024382-199603000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wada H, Wakita Y, Nakase T et al. . Outcome of disseminated intravascular coagulation in relation to the score when treatment was begun. Mie DIC Study Group. Thromb Haemost 1995;74:848–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi N, Maekawa T, Takada M et al. . Criteria for diagnosis of DIC based on the analysis of clinical and laboratory findings in 345 DIC patients collected by the Research Committee on DIC in Japan. Bibl Haematol 1983:265–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF et al. . Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med 2001;344:699–709. 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ranieri VM, Thompson BT, Barie PS et al. . Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in adults with septic shock. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2055–64. 10.1056/NEJMoa1202290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casserly B, Gerlach H, Phillips GS et al. . Evaluating the use of recombinant human activated protein C in adult severe sepsis: results of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign. Crit Care Med 2012;40:1417–26. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823e9f45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalil AC, LaRosa SP. Effectiveness and safety of drotrecogin alfa (activated) for severe sepsis: a meta-analysis and metaregression. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:678–86. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70157-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warren BL, Eid A, Singer P et al. . Caring for the critically ill patient. High-dose antithrombin III in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;286:1869–78. 10.1001/jama.286.15.1869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gando S, Saitoh D, Ishikura H et al. . A randomized, controlled, multicenter trial of the effects of antithrombin on disseminated intravascular coagulation in patients with sepsis. Crit Care 2013;17:R297 10.1186/cc13163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iba T, Saito D, Wada H et al. . Efficacy and bleeding risk of antithrombin supplementation in septic disseminated intravascular coagulation: a prospective multicenter survey. Thromb Res 2012;130:e129–33. 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iba T, Saitoh D, Wada H et al. . Efficacy and bleeding risk of antithrombin supplementation in septic disseminated intravascular coagulation: a secondary survey. Crit Care 2014;18:497 10.1186/s13054-014-0497-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abraham E, Reinhart K, Opal S et al. . Efficacy and safety of tifacogin (recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor) in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:238–47. 10.1001/jama.290.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abraham E, Reinhart K, Svoboda P et al. . Assessment of the safety of recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor in patients with severe sepsis: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, single-blind, dose escalation study. Crit Care Med 2001;29:2081–9. 10.1097/00003246-200111000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wunderink RG, Laterre PF, Francois B et al. . Recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor in severe community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:1561–8. 10.1164/rccm.201007-1167OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vincent JL, Ramesh MK, Ernest D et al. . A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase 2b study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin, ART-123, in patients with sepsis and suspected disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care Med 2013;41:2069–79. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828e9b03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhiyong L, Hong Z, Xiaochun M et al. . Heparin for treatment of sepsis: a systemic review. Chin Crit Care Med 2014;26:135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.