Highlights

-

•

Subdural empyema is difficult to differentiate from meningitis on clinical examination alone.

-

•

CT or MRI imaging must be performed for definitive diagnosis.

-

•

Prompt diagnosis, IV antibiotics and neurosurgical evacuation improve morbidity and mortality.

-

•

Use of prophylactic anticonvulsants and wide-exposure craniotomy are recommended.

-

•

Streptococcus pluranimalium needs to be further studied to assess for zoonotic potential.

Keywords: Subdural empyema, Intracranial abscess, Complicated sinusitis, Streptococcus pluranimalium, Subclinical sinusitis

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

We present the first case of a subdural empyema caused by Streptococcus pluranimalium, in a healthy adolescent male as a possible complication of subclinical frontal sinusitis. Clinical features, diagnostic approach and management of subdural empyema are discussed.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

A 17-year-old male with a 2 day history of headache and nausea was referred to our Emergency Department (ED) as a case of possible meningitis. He was afebrile, lethargic and drowsy with significant neck stiffness on examination. Computerized tomography (CT) revealed a large frontotemporoparietal subdural fluid collection with significant midline shift. Subsequent contrast-enhanced CT established the presence of intracranial empyema; the patient underwent immediate burr-hole evacuation of the pus and received 7 weeks of intravenous antibiotics, recovering with no residual neurological deficit.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of subdural empyema as a complication of asymptomatic sinusitis in an immunocompetent patient with no history of fever or upper respiratory symptoms was unanticipated. Furthermore, the organism Streptococcus pluranimalium that was cultured from the pus has only been documented twice previously in medical literature to cause infection in humans, as it is primarily a pathogen responsible for infection in bovine and avian species.

CONCLUSION

Subdural empyema represents a neurosurgical emergency and if left untreated is invariably fatal. Rapid diagnosis, surgical intervention and intensive antibiotic therapy improve both morbidity and mortality.

1. Case presentation

A 17-year-old French male of African ethnicity, was referred to our hospital as a case of possible meningitis from the Airport Medical Center. He reported vomiting once 3 days prior to presentation after which he was asymptomatic for 1 day; over the consequent 2 days he complained of worsening frontal headache associated with photophobia, nausea, loss of appetite, decreased sleep and generalized fatigue. He denied any history of fever, neck pain, seizures, rash, head trauma, upper respiratory symptoms or sick contacts. The patient was a student from France and had spent the 7 days prior to presentation in Dubai on vacation with his family. He had no relevant past medical, surgical, family or social history, and was not on any medications.

On examination he appeared very lethargic, mildly dehydrated and drowsy. Initial vitals were blood pressure 92/55 mmHg, heart rate (HR) 63/min, respiratory rate 16/min and temperature 36.5 °C. On neurological examination the patient was oriented, Glasgow Coma Scale 14/15 (Eye opening: 3/4), had significant nuchal rigidity, Kernig's sign positive, diminished reflexes (1+) and increased tone. At this time there were no focal motor or sensory deficits. All other systemic examination was unremarkable.

2. Investigations

Laboratory data was significant for leukocytosis of 14,400 cells/mm3 with 84% neutrophils, and elevated C-Reactive Protein 120 mg/L, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate 64 mm/1 h and Procalcitonin 3.09 ng/mL (High risk of progression to severe systemic infection). A Basic Metabolic panel showed a low serum Sodium of 125 mmol/L and further testing revealed low Serum Osmolality (273 mOsm/kg water), with high Urine Osmolality (940 mOsm/kg water) and elevated Urinary Sodium (75 mmol/L). Electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed sinus bradycardia with an escape junctional rhythm (HR 40–65/min); all other investigations were within normal limits. A provisional diagnosis of Bacterial Meningitis with Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion (SIADH) was made, and the patient was sent for CT scanning prior to lumbar puncture.

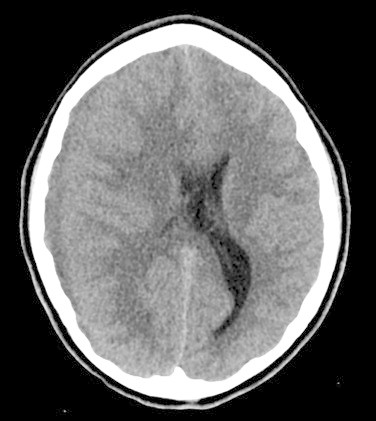

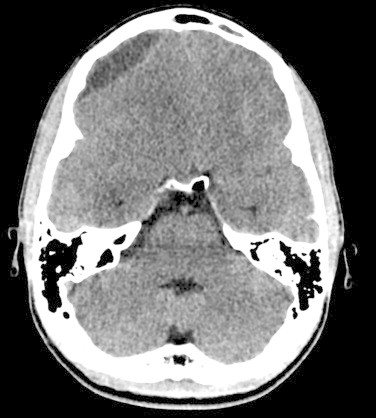

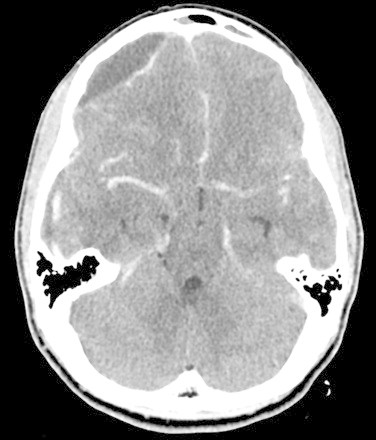

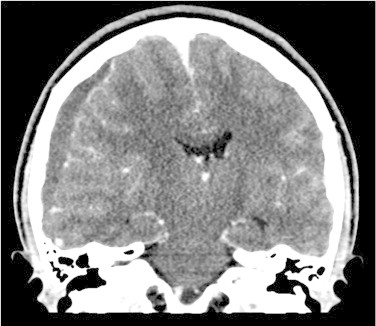

Initial noncontrast CT Brain showed diffuse cerebral edema and a well-defined extra axial fluid (subdural) collection in the right fronto-temporo-parietal region causing mass effect on the underlying cerebral parenchyma and ventricular system with significant midline shift to the left (Fig. 1), the collection also appeared to have an epidural component in the right frontal region (Fig. 2). To be able to definitively identify the cause of the collection (resolving hematoma versus abscess) an intravenous contrast-enhanced CT was performed, which demonstrated peripheral enhancement of the frontal epidural collection (Fig. 3) and subtle enhancement of the fronto-temporo-parietal subdural collection (Fig. 4) with almost complete diffuse mucosal thickening of the left frontal sinus.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative non-contrast computed tomography (axial view) demonstrating right temporo-parietal collection causing mass effect on the underlying cerebral parenchyma and ventricular system with midline shift to the left.

Fig. 2.

Preoperative non-contrast computed tomography (axial view) revealed a possible epidural component of the collection in the right frontal region, which was intraoperatively noted to also be subdural.

Fig. 3.

Preoperative contrast-enhanced computed tomography (axial view) showing peripheral enhancement of the frontal collection.

Fig. 4.

Preoperative contrast-enhanced computed tomography (coronal view) demonstrating subtle enhancement of the subdural collection.

The diagnosis of subdural empyema was made, urgent neurosurgical intervention was planned and the patient was immediately started on intravenous (IV) Ceftriaxone, Metronidazole and Vancomycin; during this time it also was noticed that the patient had developed an upper motor neuron type left facial weakness.

3. Treatment

Intra-operatively an initial right parietal burr-hole was made, the dura was incised and a large amount of yellow, liquefied, odorless pus was drained (Fig. 5). A second burr-hole was made in the frontal region and once again a large amount of pus was drained; upon irrigation a subdural communication between the frontal and parietal burr-holes was confirmed. As there was a communication and the pus was not thick the procedure was limited to burr-holes only. After copious irrigation a subdural drain was placed under low pressure through the frontal burr hole and the wound was closed.

Fig. 5.

Intraoperative photograph demonstrating yellow liquefied pus upon incision of the dura.

On Day 1 postoperatively, the patient had a generalized tonic-clonic seizure and three episodes of vomiting associated with headache. He was started on IV Phenytoin 100 mg every 8 h, Vancomycin 1 g every 12 h, Metronidazole 500 mg every 8 h and Ceftriaxone 2 g every 12 h. Over the next week he continued to have several episodes of vomiting associated with fever; however there were no more seizures, focal neurological deficits or any deterioration in his condition.

Gram staining of the pus showed gram-positive cocci and gram-negative rods. By Day 4 there was heavy growth of Streptococcus pluranimalium on all culture media, with sensitivity to Benzylpenicillin, Clindamycin, Erythromycin, Vancomycin, Linezolid and Cefepime; the colonies were identified using the VITEK®2 (bioMérieux) bacterial identification system. The gram-negative rods failed to grow on any of the culture media, and blood cultures taken were also negative.

Following the culture results, IV Metronidazole and Ceftriaxone were discontinued and he was started on Meropenem 2 g IV every 8 h with Vancomycin 1 g every 12 h.

4. Patient outcome

The patient's general condition gradually improved, his cardiac rhythm returned to normal sinus, neurologic examination remained nonfocal, and by Day 7 post-op he was no longer febrile and was free of headaches; on further questioning he denied any past history of sinusitis or any exposure to live cattle or poultry. On the 13th postoperative day the patient traveled home to France, with instructions for hospital admission and to continue IV antibiotics for a minimum of 4–6 weeks, with close neurosurgical and otorhinolaryngology follow-up.

We were informed that the patient received 5 weeks of IV antibiotics in France, and was diagnosed to have a long standing dental infection, which was posited as another possible source of the subdural spread. Unfortunately, neither source was sampled for definitive confirmation as a primary focus. The patient was ultimately discharged with no neurological deficit and with instructions for intensive dental follow-up.

5. Discussion

A subdural empyema (SDE) is a loculated collection of purulent material between the dura and the arachnoid mater, accounting for 20% of all intracranial infections. It represents a neurosurgical emergency which is inevitably life threatening if left untreated and may result in serious neurological deficits if the diagnosis and treatment is delayed.1

Agrawal et al.1 in a review of SDE reported that in the neonate and infant population the most common source of primary infection was purulent meningitis, and in older children and adolescents it is usually due to direct extension from oto-rhinogenic causes such as middle ear or paranasal sinus infections, with other causes including spread from distant sites (such as the lungs and oral cavity), post-neurosurgical interventions and as a complication of penetrating head trauma. The infection appears to have a predilection for the male gender, with over 60–80% of reported cases in men in their second to third decade of life.1,2

With no pathognomonic sign or symptom, initial clinical presentation may be impossible to differentiate from meningitis. A large clinical series of 699 cases of SDE reported fever, neck stiffness, headache, and focal seizures as the most common presenting features; more importantly 280 patients in the series underwent inappropriate lumbar punctures with neurological deterioration reported in 33 cases and 3 deaths as a direct result of the procedure.2 Therefore, it is highly recommended that prior to lumbar puncture either CT or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) be performed in any patient with clinical signs of intracranial infection with altered mental status or focal neurological deficits. Furthermore, due to the localized capsulation of the SDE lumbar puncture results are most often non-specific and MRI with gadolinium enhancement represents the gold standard diagnostic modality; however contrast-enhanced CT may be more easily available and rapidly accessible at many centers and may also be used reliably for diagnosis. Laboratory investigations are again non-specific for SDE, most often showing leukocytosis with elevated Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate and C-Reactive Protein values.1,3,4 Cardiac dysrhythmias are not uncommon in patients with Central Nervous System dysfunction,5 and the sinus bradycardia with escape junctional rhythm that was seen in our patient was most likely centrally mediated.

Once diagnosis is made, immediate neurosurgical drainage with intravenous antibiotic therapy must be initiated. Either burr-hole drainage or craniotomy may be performed for irrigation of the subdural space; wide craniotomy appears to be more effective with improved outcomes due to better exposure and a more complete evacuation of the purulent collection. In our case only burr-hole drainage was performed as intraoperatively the pus was found to be very thin, nonloculated, and washed out completely with gentle irrigation and this was also confirmed on post-operative CT scanning. However, in light of the numerous studies that show wide-exposure craniotomy as the more superior surgical option, we recommend that it is considered in cases with a more protracted history, thick loculated pus, and large collections with significant cerebral edema noted on preoperative imaging, as craniotomy allows for better empyema clearance, lower reoperation rates, better antibiotic penetration with improved morbidity and mortality.6,7 It is also recommended that the primary source of infection be simultaneously eradicated (whether otogenic or sinogenic), as this results in a significant reduction in recollection of infected material and the need for repeat surgical intervention.1,8 It is also prudent to consider the use of prophylactic anticonvulsants in patients with SDEs, especially considering that in some studies up to 32% of patients already receiving prophylactic anticonvulsants still developed seizures postoperatively.9 Residual neurological deficits and persistent seizures appear to be the most common long-term complications following a SDE.6,9

Recommendations for empiric IV antibiotics from available case series include the use of a third generation cephalosporin plus Metronidazole and either Oxacillin, Vancomycin or Nafcillin for a minimum duration of 4–6 weeks.1,3 Anaerobic and microaerophilic streptococci (S. anginosus group) are reported to be the most commonly cultured organisms from SDEs of oto-rhinogenic origin, with Staphylococcus aureus more commonly seen in post-traumatic or post-operative SDE.1

Streptococcus pluranimalium is one of the newer strains of Streptococcus, first identified by Devriese et al. in 1999; the authors coined the term ‘pluranimalium’ meaning ‘from many animals’ (pluris many, animalium from animals) due to the fact that this particular species was isolated on several different animal hosts.10 Over the years since the strain was first described, it has been identified as a causative pathogen in septicemia and valvular endocarditis in broiler chickens,11 subclinical mastitis in dairy cows10 and purulent meningoventriculitis in a calf,12 it has also been associated with many bovine reproductive diseases such as abortion, stillbirth, vulvitis, vaginitis and metritis.13,14

An extensive search of literature failed to reveal any reported cases of subdural empyema in humans caused by Streptococcus pluranimalium; therefore it appears that ours would be the first. Moreover, we could only find two other cases where S. pluranimalium was isolated in humans; the authors of the first paper describe only that the strain was grown on blood cultures taken during a febrile episode in a neutropenic patient,15 the second reported case being in a 53 year old female who presented with septic arthritis and consequently died from septic shock where S. pluranimalium was grown on blood culture as well as pus aspirated from the infected joint.16

Our patient denied any contact with farm or even domestic animals prior to hospitalization, so it is unclear how he would have acquired this particular pathogen, moreover, whether this means S. pluranimalium has the potential for zoonosis is also uncertain and requires further investigation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding was required in preparation of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

LA, SS, YK and HKNK are the emergency medicine residents who were involved in the initial care of the patient and were responsible for the acquisition of patient information, literature research and drafting of the manuscript. LMA was the neurosurgeon treating the patient and was involved in the reviewing and editing of the manuscript critically for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their heartfelt appreciation to Dr. Firas Jafar Kareem Annajjar and Dr. Michael Jalal, the Program Directors of the Emergency Medicine Residency program at the Rashid Hospital Trauma Center, for the unwavering support and motivation they provide us with every day.

References

- 1.Agrawal A., Timothy J., Pandit L., Shetty L., Shetty JP. A review of subdural empyema and its management. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2007;15(3):149–153. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathoo N., Nadvi S.S., van Dellen J.R., Gouws E. Intracranial subdural empyemas in the era of computed tomography: a review of 699 cases. Neurosurgery. 1999;44(3):529–535. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199903000-00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Bonis P., Anile C., Pompucci A., Labonia M., Lucantoni C., Mangiola A. Cranial and spinal subdural empyema. Br J Neurosurg. 2009;23(3):335–340. doi: 10.1080/02688690902939902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holland A.A., Morriss M., Glasier P.C., Stavinoha P.L. Complicated Subdural Empyema in an adolescent. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2013;28(1):81–91. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acs104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller C., Williams A. Cardiac dysrhythmias associated with central nervous system dysfunction. J Neurosci Nurs. 1993;25(6):349–355. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199312000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nayan S.A., Haspani M.S.M., Latiff A.Z.A., Abdullah J.M., Abdullah S. Two surgical methods used in 90 patients with intracranial subdural empyema. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:1567–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nathoo N., Nadvi S.S., Gouws E., van Dellen J.R. Craniotomy improves outcomes for cranial subdural empyemas: computed tomography-era experience with 699 patients. Neurosurgery. 2001;49(4):872–878. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200110000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayonne E., Kania R., Tran P., Huy B., Herman P. Intracranial complications of rhinosinusitis. A review: typical imaging data and algorithm of management. Rhinology. 2009;47(1):59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.French H., Schaefer N., Keijzers G., Barison D., Olson S. Intracranial subdural empyema: a 10-year case series. Ochsner J. 2014;14(2):188–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devriese L.A., Vandamme P., Collins M.D., Alvarez N., Pot B., Hommez J. Streptococcus pluranimalium sp. nov.: from cattle and other animals. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49(3):1221–1226. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-3-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedegaard L., Christensen H., Chadfield M.S., Christensen J.P., Bisgaard M. Association of Streptococcus pluranimalium with valvular endocarditis and septicaemia in adult broiler parents. Avian Pathol. 2009;38(2):155–160. doi: 10.1080/03079450902737763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seimiya Y.M., Takahashi M., Kudo T., Sasaki K. Meningoventriculitis caused by Streptococcus pluranimalium in a neonatal calf of premature birth. J Vet Med Sci. 2007;69(6):657–660. doi: 10.1292/jvms.69.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Twomey D.F., Carson T., Foster G., Koylass M.S., Whatmore A.M. Phenotypic characterisation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis of veterinary isolates of Streptococcus pluranimalium. Vet J. 2012;192(2):236–238. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster G., Hunter L., Baird G., Koylass M.S., Whatmore A.M. Streptococcus pluranimalium in ovine reproductive material. Vet Rec. 2010;166(8) doi: 10.1136/vr.c979. 246-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paolucci M., Stanzani M., Melchionda F., Tolomelli G., Castellani G., Landini M.P. Routine use of a real-time polymerase chain reaction method for detection of bloodstream infections in neutropaenic patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;75(2):130–134. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacob E., Kiran S., Jithendranath A., Sheetal S., Gigin S.V. Streptococcus pluranimalium-close encounter of a new kind. J Assoc Physicians India. 2014;62 http://www.japi.org/oral_Feb_2014/poster_Infectious_Diseases.html Available from: [accessed 02.06.14] [Google Scholar]