Highlights

-

•

An 86-year-old woman with a history of cholelithiasis presented with abdominal pain and nausea.

-

•

Imaging demonstrated pneumobilia, bowel dilation, and a 3.5 cm gallstone in the sigmoid colon.

-

•

Conservative management, enemas, and an attempt to ensnare the gallstone by colonoscopy, failed.

-

•

The patient underwent a sigmoid resection and a Hartmann’s procedure for gallstone perforation.

-

•

She was discharged after a complicated post-operative course and has returned to her baseline.

Keywords: Colon, Sigmoid, Obstruction, Perforation, Gallstone

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Herein we present the case of an 86-year-old woman with gallstone perforation of the sigmoid colon.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

An 86-year-old woman with known cholelithiasis presented to our office with one week of abdominal pain and nausea. X-rays taken at presentation demonstrated pneumobilia, and CT scan showed a 3.5 cm gallstone in the sigmoid colon. Medical management was unsuccessful in passing the stone, and a colonoscopy on day 4 was unsuccessful in incorporating the stone. Subsequent clinical deterioration prompted a laparotomy, where a perforation was discovered. A Hartmann's procedure was performed and the patient recovered after a complicated post-operative course.

DISCUSSION

Gallstone ileus is an uncommon, but medically important, cause of bowel obstruction. This presentation is considered a surgical emergency and thus prompt identification and removal is essential. Obstructions tend to occur in either the stomach or along the various segments of the small intestine but have been reported in the colon as well.

CONCLUSION

In cases of gallstones that manage to pass into the large intestine, it is prudent to attempt conservative measures for passage. Failure to do so should raise suspicion of a possible stricture, either benign or malignant, preventing its evacuation. Earlier surgical intervention should be considered in these cases.

1. Introduction

Gallstone ileus is a rare cause of gastrointestinal obstruction, accounting for 1–3% of cases. In one large review of 1001 cases,1 the average age was 72 years old with a female predominance of 3.5:1. While indeed gallstones may cause obstruction at any point along their course through the gastrointestinal tract, they have a predilection to obstruct the smaller-caliber lumen of the small intestine (80.1%) or stomach (14.2%). Less frequently these stones may become lodged in and cause obstruction of the colon (4.1%) and in very rare cases perforation. Prompt diagnosis and management, often surgical removal, is necessary to avoid any complications associated with gallstone ileus.

2. Presentation of case

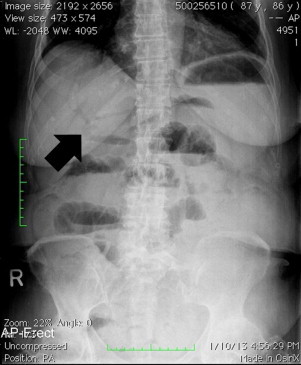

An 86-year-old woman presented to the office with a one-week history of intermittent abdominal pain and nausea. Two days prior to presentation she became constipated, obstipated, and noticed foul smelling eructation. Her medical history was significant for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, colelithiasis discovered two years prior but left untreated. Her surgical history was significant for an umbilical hernia repair in childhood. The decision was made to admit her to the surgical service for further evaluation of suspected bowel obstruction. An abdominal film soon after admission showed dilation of the small bowel along with air in the biliary tree [Fig. 1]. She then experienced two episodes of emesis. A nasogastric tube was inserted for decompression. Subsequent CT scan on that day showed pneumobilia, bowel dilation, and a 3.5 cm gallstone in the sigmoid without any distension of the proximal colon [Fig. 2]. A cholecystoduodenal fistula was identified. Because the gallstone had traversed the ileocecal valve, the decision was made for further conservative management given her age and multiple comorbidities. She was given several enemas over the next 48 h which were unsuccessful in passing the stone Table 1.

Fig. 1.

An abdominal film shows dilated small bowel and pneumobila (black arrow).

Fig. 2.

Coronal, sagittal, and transverse CT imaging shows a 3.5 cm gallstone (white arrows) in the sigmoid colon.

Table 1.

Summary of the five previously reported cases of gallstone perforation of the large intestine.

| Author (year) | Patient age/sex | Site of perforation | Gallstone size | Surgical procedure | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bollack et al. (1956) | 59 F | Sigmoid | Unknown | Hartmann's | Died 24 h post-operative |

| Van Kerschaver et al. (2009) | 72 M | Sigmoid | 4 cm | Hartmann's | Patient discharged, eventually underwent intestinal continuity |

| Quereshi et al. (2009) | 79 F | Sigmoid | 6 cm | Hartmann's | Unknown |

| Schoofs et al. (2010) | 88 F | Sigmoid | 4.7 cm | Hartmann's | Developed acute renal failure, died from acute myocardial infarction 6 weeks later |

| D’Hondt et al. (2011) | 87 F | Sigmoid | 4.2 cm | Hartmann's | Unknown |

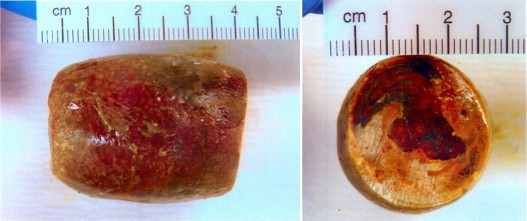

On hospital day 4, a water-soluble contrast enema was performed which demonstrated a large filling defect in the mid sigmoid colon at the site identical to the prior CT finding [Fig. 3]. Colonoscopy was subsequently attempted, but unsuccessful in incorporating the stone. Following the colonoscopy, the patient reported increased abdominal discomfort. The decision was made then to take the patient to the operating room for laparotomy. There was a large amount of fibrinous exudate and contamination throughout the abdominal cavity. The sigmoid was found to be ulcerated and inflamed with multiple extensive diverticula throughout. A small perforation was visible in the anterior surface. The sigmoid colon was resected and a Hartmann's procedure performed. Both the gallbladder and choledochoduodenal fistula were left untouched. The pathology report described a 3.7 cm × 3.0 cm × 2.7 cm barrel-shaped gallstone [Fig. 4]. Of note, there was an area of stricture around the level of the perforation located 8.5 cm from the distal margin with a luminal circumference narrowed to 3.5 cm [Fig. 5]. The proximal mucosa was prominently edematous with pseudopolypoid discoloration and deep invaginations of mucosa which extend to the wall in the vicinity of the vicinity of the serosal exudate.

Fig. 3.

A water-soluble enema demonstrates the gallstone (black arrow) at the level of the sigmoid colon.

Fig. 4.

3.7 cm × 3.0 cm × 2.7 cm barrel-shaped gallstone.

Fig. 5.

Area of stricture in the sigmoid colon around the level of the perforation with a luminal circumference narrowed to 3.5 cm.

The patient's post-operative course was complicated by septic shock, oliguric acute renal failure, and respiratory failure requiring intubation and ICU care. She responded to aggressive management and was discharged to the medical floor on post-operative day 8. She continued to improve and was transferred for long-term rehabilitation on post-operative day 16. The patient has returned to her prior baseline of health and continues to follow at our office.

3. Discussion

Gallstones are a common, often incidental, finding in adults.2 Major risk factors for gallstones include age, female sex, and obesity.3 Diabetes is also implicated in the disease.4,5 Fistula formation between the gallbladder and the small intestine is a rare event1 but may occur. Gallstones most commonly gain entry to the gastrointestinal tract via cholecystoduodenal fistulas but can also enter via cholecystocolonic and cholecystogastric fistulas.6 Imaging remains an important modality in the prompt diagnosis of gallstone ileus. The eponym “Rigler's triad” describes the findings of pneumobilia, small bowel obstruction, and gallstone, on X-ray and are considered pathognomonic, but all three are only seen in approximately one third of cases7 of gallstone ileus.

Gallstone ileus causing obstruction of the colon is a rare medical finding. Gallstones causing colonic perforation are rarer yet. A PubMed search yielded only 5 reported cases [Fig. 1].8–12 As such, there is a paucity of information detailing the optimal management of these patients. We suspected a small bowel obstruction based on the initial history and physical exam. Subsequent X-ray revealed a small bowel obstructive pattern, but also pneumobilia which raised our suspicion of gallstone ileus. A CT scan was ordered to better visualize the lesion and showed the gallstone at rest in the sigmoid colon. Given that the stone had passed through the ileocecal valve into the larger caliber colon, we reasonably expected that the stone would pass spontaneously. Aiding our decision to approach this patient conservatively, in addition to her advanced age and multiple comorbidities, was the fact that she remained afebrile, hemodynamically stable, and showed no peritoneal signs. She was observed closely for deterioration of her clinical status while an initial nonsurgical approach was attempted.

When she failed to progress by day 4, a water-soluble contrast enema [Fig. 3] was performed to better visualize the degree of obstruction and to ascertain the reason for the failure to pass the gallstone. Identification of the stone in the position identical to the prior CT prompted colonoscopy in a final attempt to remove the stone in a non-operative fashion. Multiple attempts to ensnare the stone were unsuccessful, although the stone was dislodged and able to be pushed proximally into the colon. Inflammation and edema was visualized at the site of obstruction which raised suspicion of a small perforation. Following colonoscopy the patient complained of more pain and exhibited more tenderness, which prompted a quick transfer to the OR for laparotomy. We believe that the stone became “uncorked,” resulting in pneumoperitoneum. Intraoperative findings were consistent with a process of several days’ duration. We hypothesize that the patient's stricture was secondary to diverticular disease although she had no documented history of diverticulitis.

There is little information in the surgical literature regarding management of choledochoduodenal fistula. It is advised that in each case, physicians consider the etiology of the fistula, severity of disease, and the overall condition of each patient when deciding whether or not to pursue a surgical correction.13 In this case, we decided to manage her fistula conservatively based on our patient's advanced age, condition, and the absence of long standing symptoms related to the fistula. We decided that surgical management of the fistula could be performed at a later date if necessary and following adequate recovery from the Hartmann's procedure. To date, she has demonstrated no symptoms and has received no further treatment concerning the choledochoduodenal fistula.

4. Conclusion

In cases of gallstones that manage to pass into the large intestine, it is prudent to attempt conservative measures for passage. Failure to do so should raise suspicion of a possible stricture, either benign or malignant, preventing its evacuation. Earlier surgical intervention should be considered in these cases.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No source of funding.

Ethical approval

As no data are being published that could violate the patient's privacy, no formal written consent was asked for.

Author contributions

Devin R. Halleran, BA (corresponding author), performed data collection, analysis, interpretation, and wrote the paper. David R. Halleran, MD, was the attending physician for the case, was responsible for study concept and design, performed the surgical operation, and edited and revised the paper.

References

- 1.Reisner R.M., Cohen J.R. Gallstone ileus: a review of 1001 reported cases. Am Surg. 1994;60:441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Everhart J.E., Khare M., Hill M., Maurer K.R. Prevalence and ethnic differences in gallbladder disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1999;117(3):632. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Völzke H., Baumeister S.E., Alte D., Hoffmann W., Schwahn C., Simon P. Independent risk factors for gallstone formation in a region with high cholelithiasis prevalence. Digestion. 2005;71(2):97–105. doi: 10.1159/000084525. [Epub 2005 Mar 16] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Santis A., Attili A.F., Ginanni Corradini S., Scafato E., Cantagalli A., De Luca C. Gallstones and diabetes: a case–control study in a free-living population sample. Hepatology. 1997;25(4):787. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman B.A., Wilson I.R., Frampton C.M., Chisholm R.J., Stewart N.R., Eagar G.M. Prevalence of gallbladder disease in diabetes mellitus. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41(11):2222. doi: 10.1007/BF02071404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Hillo M., van der Vliet J.A., Wiggers T., Obertop H., Terpstra O.T., Greep J.M. Gallstone obstruction of the intestine: an analysis of ten patients and a review of the literature. Surgery. 1987;101(3):273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doko M., Zovak M., Kopljar M., Glavan E., Ljubicic N., Hochstädter H. Comparison of surgical treatments of gallstone ileus: preliminary report. World J Surg. 2003;27:400–404. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6569-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Hondt M., D’Haeninck A., Penninckx F. Gallstone ileus causing perforation of the sigmoid colon. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(April (4)):701–702. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1387-4. [Epub 2010 Nov 16] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoofs C., Vanheste R., Bladt L., Claus F. Cholecystocolonic fistula complicated by gallstone impaction and perforation of the sigmoid. JBR-BTR. 2010;93(January–February (1)):32. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qureshi N.A., Dua S., Leonard O., Myint F. Faecal peritonitis secondary to perforated recto sigmoid colon by a large gallstone: a case report. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;200:9. doi: 10.1136/bcr.10.2008.1105. [pii:bcr10.2008.1105. Epub 2009 Mar 17] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Kerschaver O., Van Maele V., Vereecken L., Kint M. Gallstone impacted in the rectosigmoid junction causing a biliary ileus and a sigmoid perforation. Int Surg. 2009;94(January–February (1)):63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bollack C. Case of perforation of sigmoid by a voluminous biliary calculus. Arch Mal Appar Dig Mal Nutr. 1956;45(July–August (7–8)):37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cong K.C., You H.B., Gong J.P., Diagnosis Tu B. Management of choledochoduodenal fistula. Am Surg. 2011;77(March (3)):348–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]