Abstract

A multitude of nanoparticles, such as titanium oxide (TiO2), zinc oxide, aluminum oxide, gold oxide, silver oxide, iron oxide, and silica oxide, are found in many chemical, cosmetic, pharmaceutical, and electronic products. Recently, SiO2 nanoparticles were shown to have an inert toxicity profile and no association with an irreversible toxicological change in animal models. Hence, exposure to SiO2 nanoparticles is on the increase. SiO2 nanoparticles are routinely used in numerous materials, from strengthening filler for concrete and other construction composites, to nontoxic platforms for biomedical application, such as drug delivery and theragnostics. On the other hand, recent in vitro experiments indicated that SiO2 nanoparticles were cytotoxic. Therefore, we investigated these nanoparticles to identify potentially toxic pathways by analyzing the adsorbed protein corona on the surface of SiO2 nanoparticles in the blood and brain of the rat. Four types of SiO2 nanoparticles were chosen for investigation, and the protein corona of each type was analyzed using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry technology. In total, 115 and 48 plasma proteins from the rat were identified as being bound to negatively charged 20 nm and 100 nm SiO2 nanoparticles, respectively, and 50 and 36 proteins were found for 20 nm and 100 nm arginine-coated SiO2 nanoparticles, respectively. Higher numbers of proteins were adsorbed onto the 20 nm sized SiO2 nanoparticles than onto the 100 nm sized nanoparticles regardless of charge. When proteins were compared between the two charges, higher numbers of proteins were found for arginine-coated positively charged SiO2 nanoparticles than for the negatively charged nanoparticles. The proteins identified as bound in the corona from SiO2 nanoparticles were further analyzed with ClueGO, a Cytoscape plugin used in protein ontology and for identifying biological interaction pathways. Proteins bound on the surface of nanoparticles may affect functional and conformational properties and distributions in complicated biological processes.

Keywords: silica, nanoparticles, protein corona, plasma, brain homogenate, nanotoxicity

Introduction

Silica oxide (SiO2) nanoparticles have become the preferred choice in the manufacture of glass and semiconducting products, and their use is on the rise.1–6 In addition, SiO2 nanoparticles are now being incorporated into building materials, such as strengthening filler for concrete and other construction composites. The potential applications of nanotechnology using SiO2 nanoparticles seem endless, with nanoparticle-based platforms now expanding in sensor and electronic devices, the food and cosmetic industries, and biomedical applications, such as drug delivery and theranostics.7–9 In biomedical research, polyethyleneimine-functionalized silica particles was selected for targeting and tracking cancer cells by designing functional groups on the surface. SiO2 nanoparticles can also be made porous, acting as nontoxic biocompatible vehicles for intracellular delivery of drugs.

In the early research on nanoparticles, their toxicity profiles were principally determined according to particle size.10 As more and more variants of SiO2 nanoparticles became available, it was apparent that size alone could not adequately explain the diverse outcomes and heterogenous toxicity profiles. More recently, in vitro experiments with SiO2 nanoparticles using the human reconstituted epidermis model (EpiDerm™ 3D, MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA, USA) have clearly shown a high degree of cytotoxicity.10,11 When 15 nm SiO2 nanoparticles were investigated for their cellular toxicity in vitro using A43 human skin epithelial cells and A549 human lung epithelial cells, their cytotoxicity was found to be due to oxidative stress and induction of apoptosis.12 Further, reduced growth of U87 human astrocytoma cells was observed on exposure to 12 nm SiO2 nanoparticles at higher concentrations (25 μg/mL).13 In vitro and in vivo studies have reported that SiO2 nanoparticles cause damage to the cardiovascular system.14 Moreover, mice treated with SiO2 nanoparticles showed signs of oxidative stress and an inflammatory response,15 with the administered nanoparticles accumulating mainly in the lung, liver, and spleen.16–18 In all cases, the cytotoxic mechanism was suggested to involve pathways for oxidative stress and induction of apoptosis in the mitochondria.19–24 On the other hand, administration of SiO2 nanoparticles in rats did not have any toxic effect, except for formation of granuloma in the liver and spleen.25

In the in vivo setting, when reconstituted nanoparticles in solution are administered via intravenous or intracerebral injection, nanoparticles would encounter proteins from blood or cerebrospinal fluid, which would influence their interactions at the cellular and tissue levels. Hence, proteomic analyses of proteins bound on the surface of nanoparticles, known as protein corona, might improve our understanding of the role of nanoparticles in activating certain cytotoxic pathways. Each surface modification would dictate the overall surface charge, size, stability, and cell specificity of nanoparticles in a targeted drug delivery, determining interactions with critical factors and the cytotoxicity and efficiency of cellular uptake. Analyzing the protein corona could also provide clues enabling prediction of the long-term effects of nanoparticles, as well as their clearance. Recently, SiO2 nanoparticles were reported to have affinity for a wide range of proteins.26 In addition, interactions between SiO2 nanoparticles and lysozymes seem to be determined by the size and structure of the nanoparticles when preferentially activating certain enzymes.27 Therefore, according to the above reports, SiO2 nanoparticles may interact with many diverse cellular and extracellular proteins, which may be influential factors for in vivo interactions.

In this work, interactions between SiO2 nanoparticles and proteins from blood and brain homogenates were analyzed for assessing their potential interactive pathways, and the adsorbed protein corona from blood and brain tissue were identified on the surface of SiO2 nanoparticles. Four types of SiO2 nanoparticles, 20 nm and 100 nm in size with positive and negative charges, were selected and investigated using a proteomics approach with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) technology. Identified bound proteins in the protein corona from SiO2 nanoparticles were further analyzed with ClueGO, a Cytoscape (National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Bethesda, MD, USA) plugin used in the investigation of protein ontology and potential interactions between SiO2 nanoparticles and biological processes, which may affect functional and conformational properties in complicated systems.

Materials and methods

Preparation of nanoparticles

SiO2 nanomaterials (20 nm and 100 nm in size) were obtained from E&B Nanotech Co, Ltd, (Gyeonggi-do, Korea). L-arginine was used to protonate the silanol groups on the surface of the SiO2 nanoparticles and inhibited hydrogen bonding.28 In brief, negatively charged 20 nm and 100 nm SiO2 nanoparticles (SiO2EN20(−) and SiO2EN100(−)) were diluted in deionized water, then vigorously mixed with L-arg (R) solution at around 298 K for one hour. The mixture was titrated using HCl solution, and physicochemical properties were verified including average size, morphology, and zeta potential.28 The mean size of the SiO2EN20(−) and SiO2EN100(−) nanoparticles was 20±2 nm and 90±13 nm, respectively, and the mean size of the 20 nm and 100 nm arginine-coated SiO2 nanoparticles (SiO2EN20(R), SiO2EN100(R)) was determined to be 21±2 nm and 92±9 nm, respectively. The zeta potentials were measured to be +60 to −20 mV (SiO2EN20(−)), −70 to +70 mV (SiO2EN20(R)), −80 to −20 mV (SiO2EN100(−)), and −60 to +60 mV (SiO2EN100(R)).

Preparation of plasma and brain homogenate

Rat plasma samples were collected in a sodium/heparin anticoagulant tube to prevent blood clotting and centrifuged for 30 minutes at 850× g to separate the plasma from blood cells. The supernatant (plasma) was transferred, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C.

Whole brains were obtained from adult rats immediately after euthanasia. The left hemisphere of the brain was stored in formalin at 4°C for immunohistochemistry. A 10% (w/v) homogenate for protein analysis was prepared as follows: samples taken from the right hemisphere of the brain were homogenized with a phosphate-buffered saline solution containing ceramic beads in a Ribolyser tube (Hybaid Ltd, Ashford, UK). This was dispensed into 2 mL tubes and centrifuged for an additional 30 minutes, after which the supernatant was stored at −80°C.

Incubation of SiO2 nanoparticles with plasma and brain homogenate

Prior to the binding experiment with SiO2 nanoparticles, plasma was centrifuged at 22,000× g for 30 minutes at 4°C, and 500 μL of supernatant were transferred into a new tube. SiO2 nanoparticle concentrations were prepared using phosphate-buffered saline. Because 20 nm SiO2 nanoparticles have a larger surface area than 100 nm SiO2 nanoparticles at the same concentration, each concentration was calculated to adjust identical surface area between 20 nm and 100 nm SiO2 nanoparticles during incubation. The 20 nm and 100 nm SiO2 nanoparticles were diluted to 0.2 mg/mL and 1 mg/mL, respectively, in phosphate-buffered saline. Rat plasma and brain homogenate were added separately to all four types of SiO2 nanoparticles, and incubated for one hour at 37°C. After incubation, the solution was centrifuged for 30 minutes at 18,000× g and then washed three times with 1 mL phosphate-buffered saline. Afterwards, the bound proteins in the SiO2 nanoparticles were analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

Analysis of proteins by LC-MS/MS

The LC-MS/MS was performed by Diatech Korea Co, Ltd, (Seoul, South Korea). The methodology used is described in detail below.

Enzymatic in-gel digestion

The proteins, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, were excised from the gel, and the pieces of gel including the proteins were destained using 50% acetonitrile with 50 mM NH4HCO3 and vortexed to completely remove the Coomassie brilliant blue. The pieces of gel were dehydrated in 100% acetonitrile and vacuum-dried with a SpeedVac® device (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) for 20 minutes. The pieces of gel were reduced by 10 mM DTT in 50 mM NH4HCO3 for 45 minutes at 56°C for digestion. Next, the cysteines were alkylated with 55 mM iodoacetamide in 50 mM NH4HCO3 for 30 minutes in the dark. Finally, each piece of gel was treated with 12.5 ng/μL sequencing grade-modified trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) in 50 mM NH4HCO3 buffer (pH 7.8) at 37°C overnight. Following digestion, 5% formic acid in 50% acetonitrile solution at room temperature for 20 minutes was used to extract the tryptic peptides. After drying the supernatants, resuspended samples in 0.1% formic acid were purified and concentrated using C18 ZipTips (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) before analysis by mass spectrometry.

Nanoliquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry

The tryptic peptides were loaded onto a fused silica micro-capillary column (12 cm × 75 μm) packed with C18 reversed phase resin (5 μm, 200 Å). Liquid chromatography separation was performed as follows: a gradient of 3%–40% solvent B (acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid) solvent A (deionized water containing 0.1% formic acid), with a flow rate of 250 nL per minute, for 60 minutes. The column was directly connected to an LTQ™ linear ion-trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corporation, CA, San Jose, USA) equipped with a nanoelectrospray ion source. The electrospray voltage was set at 1.95 kV. The threshold for switching from mass spectrometry to tandem mass spectrometry was 500. The collision energy for tandem mass spectrometry was 35% of the main radio frequency amplitude. The duration of activation was 30 msec. All spectra were acquired in data-dependent scan mode. Each mass spectrometry scan was preceded by five tandem mass spectrometry scans corresponding to the most intense to the fifth most intense peaks of the full mass spectrometry scan. Repeat count of peak for dynamic exclusion was 1, and its repeat duration was 30 seconds. The duration of dynamic exclusion was set for 180 seconds. Width of exclusion mass was ±1.5 Da, and the list size of dynamic exclusion was 50.

Database searching and validation

The acquired liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry fragment spectra were searched in the BioWorksBrowser™ (version Rev. 3.3.1 SP1, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) with the SEQUEST search engines against the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) nonredundant Mus musculus database (August 20, 2008 version). The searching conditions were trypsin enzyme specificity, a permissible level for two missed cleavages, peptide tolerance; ±2 amu, a mass error of ±1 amu on fragment ions, and fixed modifications of carbamidomethylation of cysteine (+57 Da) and oxidation of methionine (+16 Da) residues. The ΔCn was 0.1, the Xcorr values were 1.8 (+1 charge state), 2.3 (+2), and 3.5 (+3), and the consensus score was 10.15 for the SEQEST criteria. The consensus score was used for the selection criteria, where the corresponding score to within 1% would have a higher degree of false discovery rate in our results.

ClueGO

Cytoscape is powerful software which can visualize the relationship between proteins and genetic interactions. The Cytoscape plugin, ClueGO, allows analysis of gene ontology and biological gene processes acting in concert with other interacting proteins.29 The ClueGO program was used to analyze the single or cluster of genes, according to the respective organ isms with different identifier types. ClueGO used precompiled files, such as GO, KEGG, and BioCarta, to increase the speed of ClueGO analysis. In this work, the biological process of GO was used to visualize the network of biological processes related to protein corona. Statistical tests were used to calculate the P-value and statistical significance for each group. Moreover, it was possible to regulate network types from detailed networks to global networks. The global network simplified the biological processes by adjusting the significance of particular genes. In contrast, the detailed network displayed very specific interacting processes. After starting the functional analysis, ClueGO displayed the visualized network interactions, an information table for associated genes, and a significance histogram for each group, as well as a chart overview of the functional groups.

Results

Plasma and brain homogenate proteins on the surface of SiO2 nanoparticles were identified and classified according to their affinity (Table 1). The number of plasma proteins within the criteria, ie, score >10.15, did not differ significantly according to the size or surface charge of the nanoparticles. More plasma proteins bound to SiO2EN20(R) (115 proteins) than to SiO2EN20(−) (48 proteins). Fewer proteins bound to 100 nm SiO2 nanoparticles than to 20 nm SiO2 nanoparticles. Regarding SiO2EN100(R) and SiO2EN100(−), 50 and 36 bound proteins were identified, respectively. Interestingly, greater numbers of proteins seemed to bind to positively charged SiO2 nanoparticles than to their negatively charged counterparts. Negatively charged proteins could be responsible for this preference through electrostatic interactions between protein and SiO2 nanoparticles. We cannot explain our finding of a larger number of proteins bound to the smaller SiO2 nanoparticles than to the larger ones. However, a plausible reason could be the increased surface area of the 20 nm SiO2 nanoparticles compared with the 100 nm SiO2 nanoparticles, which allowed greater numbers of proteins to bind onto the surface.

Table 1.

Number of total proteins belonging within and outside criteria proteins according to type of SiO2 nanoparticle

| Diameter | Samples | Charge | Total proteins | Within criteria | Outside of criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 nm | Plasma | + | 132 | 115 | 24 |

| − | 52 | 48 | 15 | ||

| Brain | + | 175 | 170 | 11 | |

| homogenate | − | 155 | 125 | 33 | |

| 100 nm | Plasma | + | 74 | 50 | 27 |

| − | 41 | 36 | 15 | ||

| Brain | + | 178 | 142 | 42 | |

| homogenate | − | 178 | 145 | 38 |

With regard to proteins from brain homogenate, 170 and 125 proteins bound to SiO2EN20(R) and SiO2EN20(−), respectively, while 142 and 145 proteins were identified on SiO2EN100(R) and SiO2EN100(−). A greater number of proteins bound onto the positively charged 20 nm SiO2 nanoparticles than onto their negatively counterparts in brain homogenate also.

The degree of similarity between the proteins was compared for the different types of nanoparticles in plasma and brain homogenate (Tables 2 and 3). Twenty-eight percent of the plasma proteins bound to SiO2EN20(R) were also bound to SiO2EN20(−), whereas SiO2EN20(−) had 67% similarity to SiO2EN20(R). This phenomenon could be caused by the positive and negative charge difference of SiO2. Fifty-six percent of the same proteins were bound to SiO2EN100(R), but 78% of the same proteins were bound to SiO2EN100(−). Comparing nanoparticles with the same charge as those mentioned above, 20 nm SiO2 had less similarity than 100 nm SiO2, which could be due to the higher number of proteins bound onto 20 nm SiO2 than onto 100 nm SiO2. For the positively charged nanoparticles, the similarity was 26% to SiO2EN20(R) and 60% to SiO2EN100(R). Fifty-four percent of the same proteins were bound to SiO2EN20(−) and 72% of the same proteins were bound to SiO2EN100(−).

Table 2.

Ratio of similarity of plasma protein coronas for different types of SiO2 nanoparticles

| Types of NPs | Total proteins | Common proteins | Similarity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge | |||

| SiO2EN20(R) | 115 | 32 | 28 |

| SiO2EN20(−) | 48 | 67 | |

| SiO2EN100(R) | 50 | 28 | 56 |

| SiO2EN100(−) | 36 | 78 | |

| Size | |||

| SiO2EN20(−) | 48 | 26 | 54 |

| SiO2EN100(−) | 36 | 72 | |

| SiO2EN20(R) | 115 | 30 | 26 |

| SiO2EN100(R) | 50 | 60 | |

Abbreviations: SiO2EN20(−), negatively charged 20 nm SiO2 nanoparticles; SiO2EN100(−) negatively charged 100 nm SiO2 nanoparticles; SiO2EN20(R), positively charged 20 nm SiO2 nanoparticles; SiO2EN100(R), positively charged 100 nm SiO2 nanoparticles; NPs, nanoparticles.

Table 3.

Ratio of similarity of brain homogenate protein coronas for different types of SiO2 nanoparticles

| Types of NPs | Total proteins | Common proteins | Similarity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge | |||

| SiO2EN20(R) | 170 | 98 | 58 |

| SiO2EN20(−) | 125 | 78 | |

| SiO2EN100(R)2 | 142 | 97 | 68 |

| SiO2EN100(−) | 145 | 67 | |

| Size | |||

| SiO2EN20(−) | 125 | 102 | 82 |

| SiO2EN100(−) | 145 | 70 | |

| SiO2EN20(R) | 170 | 114 | 67 |

| SiO2EN100(R) | 142 | 80 | |

Abbreviations: SiO2EN20(−), negatively charged 20 nm SiO2 nanoparticles; SiO2EN100(−) negatively charged 100 nm SiO2 nanoparticles; SiO2EN20(R), positively charged 20 nm SiO2 nanoparticles; SiO2EN100(R), positively charged 100 nm SiO2 nanoparticles; NPs, nanoparticles.

Unlike plasma proteins, proteins from brain homogenate showed the higher degree of similarity. When they were compared according to size and charge, a similar percentage was shown between the two groups. Approximately 70% of the same proteins were bound to both SiO2EN20(R) and SiO2EN20(−), and also to SiO2EN100(R) and SiO2EN100(−). Similar results were found when they were compared according to charge, ie, 20 nm and 100 nm SiO2 had approximately 75% similarity at positive and negative charges.

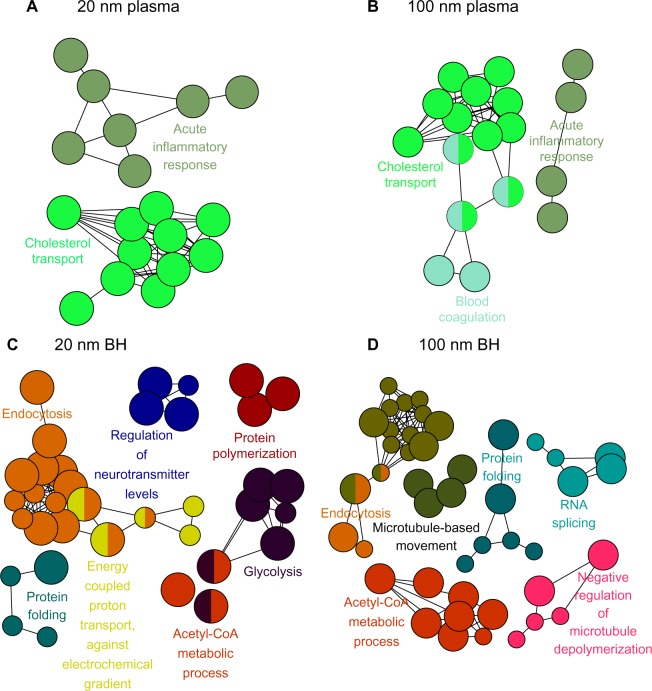

Proteins within the criteria were further analyzed using ClueGO, one of the Cytoscape plugins, which provides the gene ontology and biological processes of proteins. Each biological process was represented by their colored circular dots. In plasma, proteins involved in the acute inflammatory response and cholesterol transport pathways were bound mainly onto SiO2EN20(−) (Figure 1). In brain homogenate, SiO2EN20(−) bound with proteins involved in the acetyl-CoA metabolic process, endocytosis, protein folding, glycolysis, energy-coupled proton transport, protein polymerization, and regulation of neurotransmitters. For plasma proteins bound onto SiO2EN100(−), the result was similar to that for SiO2EN20(−), where proteins involved in the acute inflammatory response and cholesterol transport were found in addition to blood coagulation proteins. Proteins involved in the acetyl-CoA metabolic process, endocytosis, and protein folding from brain homogenate bound to both SiO2EN100(−) and SiO2EN20(−), along with proteins involved in microtubule-based movement, negative regulation of microtubule depolymerization, and RNA splicing.

Figure 1.

Visualized biological processes associated with binding of proteins from plasma and brain homogenate with SiO2 nanoparticles. (A) Plasma and negatively charged 20 nm SiO2 nanoparticles, (B) plasma and negatively charged 100 nm SiO2 nanoparticles, (C) brain homogenate and negatively charged 20 nm SiO2 nanoparticles, and (D) brain homogenate and negatively charged 100 nm SiO2 nanoparticles.

Abbreviation: BH, brain homogenate.

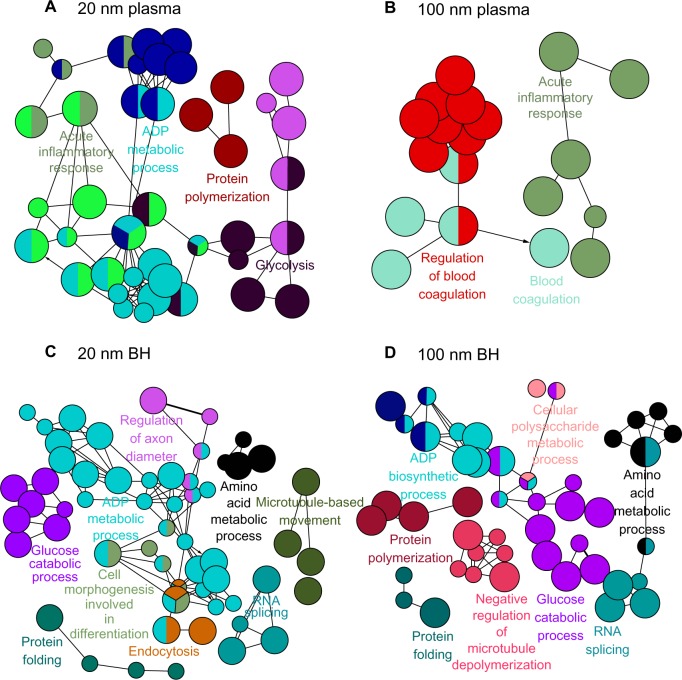

As with SiO2EN20(−), proteins involved in the acute inflammatory response bound to SiO2EN20(R), including proteins from glycolysis, protein polymerization, and the biosynthetic process for adenosine diphosphate (Figure 2). In brain homogenate, SiO2EN20(R) bound with proteins from endocytosis and protein folding, as in case with SiO2EN20(−); moreover, proteins involved in cell morphogenesis, including those for differentiation, biosynthesis of adenosine diphosphate, glucose catabolism, regulation of axon diameter, RNA splicing, amino acid metabolism, and microtubule-based movement, were also found. The plasma protein results for SiO2EN20(R) were similar to those for SiO2EN100(−) with proteins involved in blood coagulation and the acute inflammatory response being found in the protein corona. In SiO2EN20(R), similar proteins of brain homogenate from protein folding, RNA splicing, and negative regulation of microtubule depolymerization were found in the protein corona, in addition to proteins involved in the metabolism of cellular polysaccharides, the biosynthetic process for adenosine diphosphate, protein polymerization, glucose catabolism, and amino acid metabolism.

Figure 2.

Visualized biological processes associated with binding of proteins from plasma and brain homogenate with SiO2 nanoparticles. (A) Plasma and positively charged 20 mm SiO2 nanoparticles, (B) plasma and positively charged 100 mm SiO2 nanoparticles, (C) brain homogenate and negatively charged 20 nm SiO2 nanoparticles, and (D) brain homogenate and positively charged 100 mm SiO2 nanoparticles.

Abbreviations: BH, brain homogenate; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; RNA, ribonucleic acid.

Discussion

The protein corona on nanoparticles may play a key role in their interactions with cells for endocytosis and their involvements in tissue level, leading to the overall toxicity or beneficial effects of an organism. Commonly, albumin, lipoprotein, acute-phase protein, immunoglobulin, complement components, and coagulation factors in human plasma would be adsorbed onto nanoparticles. Meanwhile, other proteins may specifically bind to nanoparticles depending on their properties, including size, surface charge, and shape.30,31

From analyses of proteomic data by LC-MS/MS, the numbers of bound proteins in plasma and brain homogenate were different for each type of SiO2 nanoparticle. More proteins bound to positively charged 20 nm SiO2 than to 100 nm nanoparticles. Positively charged SiO2 were prepared using adsorption of arginine, which led to a reduction in the number of deprotonated silanol groups, probably type (II), and a stabilization of protein–protein interactions on the surface of the nanoparticle. More proteins from brain homogenate bound to both types of SiO2 nanoparticle, irrespective of particle size or shape.

Each nanoparticle was compared for its similarity and difference between bound proteins from plasma or brain homogenate. In our previous report, when ZnO nanoparticles were compared, greater differences were found between the two different sizes of nanoparticles instead of between charge differences. Various proteins were adsorbed, depending on the type of nanoparticle. On the other hand, SiO2 did not show any tendency of similarity and difference among different SiO2 NPs by their sizes and charges. Other published papers also report differential adsorption onto the surface of nanoparticles, depending on their size, surface charge, and different cell media, which would affect the cellular interactions in the next stage of nanoparticles’ pathways.32,33 These discordances could be resulted in determining different biological activities.

In comparison with results for ZnO and SiO2 nanoparticles against plasma, mainly lipoprotein, acute-phase protein, and proteins involved in the coagulation and complement pathways bound with both nanoparticles, and interestingly, albumin or immunoglobulin only bound to SiO2, not ZnO nanoparticles. Other publications suggest that proteins present at high concentration would adhere to the surface of nanoparticles first, followed by exchanges with higher affinity proteins.34,35 For instance, albumin might have a lower affinity for ZnO, whereas it would have a higher affinity for SiO2. On the other hand, lipoprotein, acute-phase proteins, and coagulation and complement factors in plasma seemed to bind strongly with ZnO and SiO2 nanoparticles.

Apolipoprotein E is another interesting protein found in the protein corona. Previously, flexible hinge regions of apolipoproteins were suggested to participate in binding interactions with ZnO and other nanoparticles, particularly given that apolipoprotein E could be involved as a mediator when nanoparticles cross the blood–brain barrier.36–38 There is some evidence that inhalation or dermal delivery of SiO2 nanoparticles resulted in crossing of the blood–brain barrier.39,40 Therefore, if SiO2 entered in the blood stream, binding to apolipoprotein E might play a role in crossing the blood–brain barrier.

Another interesting protein was fibrinogen from plasma, which existed in high concentrations of approximately 170 μg/mL. Fibrinogen is involved in many biological processes in the body from blood coagulation, promotion of attachment of immune cells, such as macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils, to binding with extracellular and foreign surfaces. SiO2 nanoparticles could induce blood coagulation or an acute inflammatory response via adsorbed fibrinogen. In a previous study, gold nanoparticles caused unfolding of fibrinogen and enhanced the interaction between fibrinogen and the integrin receptor, Mac-1.41 Fibrinogen and complement proteins were abundantly adsorbed, indicating that interaction between fibrinogen/complement proteins and SiO2 may lead to an inflammatory response. For example, complement proteins bound to carbon nanotubes can induce complement activation via both classical and alternative pathways.42 Other reports suggest that interaction between plasma components and nanoparticles can cause hemolysis, aggregation of thrombocytes, and activation of complement.43,44

Tubulin was the major protein bound onto the surface of SiO2 nanoparticles in brain homogenate. Protein ontology from ClueGO clearly indicates the biological process of tubulin. A recent report suggests that cytotoxicity and cell death are initiated by the interactions between tubulin and fullerene and involve disruption of the cytoskeleton and accumulation of autophagic vacuoles.45 Hence, interaction between nanoparticles and tubulin could also initiate disruption of the cytoskeleton, leading to accumulation of autophagic vacuoles.

Disruption of protein folding by SiO2 is becoming a popular research topic, in particular because of its potential involvement in a number of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Currently, there is no indication that nanoparticles can cause protein fibrillation or neurodegenerative disease, but protein unfolding would affect the loss in their protein functions due to binding onto the surface of nanoparticles. In addition, these altered conformation of proteins might also initiate protein aggregations in their contributions protein misfolding diseases.46

Conclusion

SiO2 nanoparticles bound mainly with albumin, lipoprotein, and proteins related to coagulation and complement system in plasma, and with tubulin in brain homogenate. The composition of the protein corona may determine the fate of nanoparticles in vivo. Other proteins could also interact with nanoparticles via proteins adsorbed at the first layer, making additional layers of protein corona. On the other hand, particle–protein interactions could be different upon endocytosis, affecting the function and conformations of proteins on the surface of other particles, as well as signal transduction.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2011 (10182MFDS991) and from the Korean National Research Foundation (2012R1A2A2A03046819).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Liu D, He X, Wang K, He C, Shi H, Jian L. Biocompatible silica nanoparticles-insulin conjugates for mesenchymal stem cell adipogenic differentiation. Bioconjug Chem. 2010;21(9):1673–1684. doi: 10.1021/bc100177v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park JH, Gu L, von Maltzahn G, Ruoslahti E, Bhatia SN, Sailor MJ. Biodegradable luminescent porous silicon nanoparticles for in vivo applications. Nat Mater. 2009;8(4):331–336. doi: 10.1038/nmat2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarn D, Ashley CE, Xue M, Carnes EC, Zink JI, Brinker CJ. Mesoporous silica nanoparticle nanocarriers: biofunctionality and biocompatibility. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46(3):792–801. doi: 10.1021/ar3000986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barandeh F, Nguyen PL, Kumar R, et al. Organically modified silica nanoparticles are biocompatible and can be targeted to neurons in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dragic P, Kucera C, Furtick J, Guerrier J, Hawkins T, Ballato J. Brillouin spectroscopy of a novel baria-doped silica glass optical fiber. Opt Express. 2013;21(9):10924–10941. doi: 10.1364/OE.21.010924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe W, Kuroda D, Itoh K, Nishii J. Fabrication of Fresnel zone plate embedded in silica glass by femtosecond laser pulses. Opt Express. 2002;10(19):978–983. doi: 10.1364/oe.10.000978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mai WX, Meng H. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles: a multifunctional nano therapeutic system. Integr Biol (Camb) 2013;5(1):19–28. doi: 10.1039/c2ib20137b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trewyn BG, Giri S, Slowing II, Lin VS. Mesoporous silica nanoparticle based controlled release, drug delivery, and biosensor systems. Chem Commun (Camb) 2007;(31):3236–3245. doi: 10.1039/b701744h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang K, He X, Yang X, Shi H. Functionalized silica nanoparticles: a platform for fluorescence imaging at the cell and small animal levels. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46(7):1367–1376. doi: 10.1021/ar3001525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park YH, Bae H, Jang Y, et al. Effect of the size and surface charge of silica nanoparticles on cutaneous toxicity. Mol Cell Toxicol. 2013;9(1):67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Musa M, Kannan T, Masudi Sa, Rahman I. Assessment of DNA damage caused by locally produced hydroxyapatite-silica nanocomposite using Comet assay on human lung fibroblast cell line. Mol Cell Toxicol. 2012;8(1):53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahamed M. Silica nanoparticles-induced cytotoxicity, oxidative stress and apoptosis in cultured A431 and A549 cells. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2013;32(2):186–195. doi: 10.1177/0960327112459206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai JC, Ananthakrishnan G, Jandhyam S, et al. Treatment of human astrocytoma U87 cells with silicon dioxide nanoparticles lowers their survival and alters their expression of mitochondrial and cell signaling proteins. Int J Nanomedicine. 2010;5:715–723. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S5238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duan J, Yu Y, Li Y, Sun Z. Cardiovascular toxicity evaluation of silica nanoparticles in endothelial cells and zebrafish model. Biomaterials. 2013;34(23):5853–5862. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park EJ, Park K. Oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory responses induced by silica nanoparticles in vivo and in vitro. Toxicol Lett. 2009;184(1):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu Y, Li Y, Wang W, et al. Acute toxicity of amorphous silica nanoparticles in intravenously exposed ICR mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie G, Sun J, Zhong G, Shi L, Zhang D. Biodistribution and toxicity of intravenously administered silica nanoparticles in mice. Arch Toxicol. 2010;84(3):183–190. doi: 10.1007/s00204-009-0488-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu T, Li L, Teng X, et al. Single and repeated dose toxicity of mesoporous hollow silica nanoparticles in intravenously exposed mice. Biomaterials. 2011;32(6):1657–1668. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye Y, Liu J, Xu J, Sun L, Chen M, Lan M. Nano-SiO2 induces apoptosis via activation of p53 and Bax mediated by oxidative stress in human hepatic cell line. Toxicol In Vitro. 2010;24(3):751–758. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu Z, Chou L, Sun J. Effects of SiO2 nanoparticles on HFL-I activating ROS-mediated apoptosis via p53 pathway. J Appl Toxicol. 2012;32(5):358–364. doi: 10.1002/jat.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Passagne I, Morille M, Rousset M, Pujalte I, L’Azou B. Implication of oxidative stress in size-dependent toxicity of silica nanoparticles in kidney cells. Toxicology. 2012;299(2–3):112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye Y, Liu J, Chen M, Sun L, Lan M. In vitro toxicity of silica nanoparticles in myocardial cells. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2010;29(2):131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rim K, Kim S, Song S, Park J. Effect of cerium oxide nanoparticles to inflammation and oxidative DNA damages in H9c2 cells. Mol Cell Toxicol. 2012;8(3):271–280. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee B, Kim K, Cho J, et al. Oxidative stress in juvenile common carp (Cyprinus carpio) exposed to TiO2 nanoparticles. Mol Cell Toxicol. 2012;8(4):357–366. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ivanov S, Zhuravsky S, Yukina G, Tomson V, Korolev D, Galagudza M. In vivo toxicity of intravenously administered silica and silicon nanoparticles. Materials. 2012;5(10):1873–1889. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shrivastava S, McCallum SA, Nuffer JH, Qian X, Siegel RW, Dordick JS. Identifying specific protein residues that guide surface interactions and orientation on silica nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2013;29(34):10841–10849. doi: 10.1021/la401985d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vertegel AA, Siegel RW, Dordick JS. Silica nanoparticle size influences the structure and enzymatic activity of adsorbed lysozyme. Langmuir. 2004;20(16):6800–6807. doi: 10.1021/la0497200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim KM, Kim HM, Choi MH, et al. Colloidal properties of surface coated colloidal silica nanoparticles in aqueous and physiological solutions. Sci Adv Mat. 2014;6(7):1573–1581. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Hackl H, et al. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(8):1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lundqvist M, Stigler J, Elia G, Lynch I, Cedervall T, Dawson KA. Nanoparticle size and surface properties determine the protein corona with possible implications for biological impacts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(38):14265–14270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng ZJ, Mortimer G, Schiller T, Musumeci A, Martin D, Minchin RF. Differential plasma protein binding to metal oxide nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2009;20(45):455101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/45/455101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fleischer CC, Payne CK. Nanoparticle surface charge mediates the cellular receptors used by protein-nanoparticle complexes. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116(30):8901–8907. doi: 10.1021/jp304630q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang H, Burnum KE, Luna ML, et al. Quantitative proteomics analysis of adsorbed plasma proteins classifies nanoparticles with different surface properties and size. Proteomics. 2011;11(23):4569–4577. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Darabi Sahneh F, Scoglio C, Riviere J. Dynamics of nanoparticle-protein corona complex formation: analytical results from population balance equations. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e64690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cedervall T, Lynch I, Lindman S, et al. Understanding the nanoparticle-protein corona using methods to quantify exchange rates and affinities of proteins for nanoparticles. Proc Natl Sci Acad U S A. 2007;104(7):2050–2055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608582104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cedervall T, Lynch I, Foy M, et al. Detailed identification of plasma proteins adsorbed on copolymer nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46(30):5754–5756. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cushley RJ, Okon M. NMR studies of lipoprotein structure. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:177–206. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.101101.140910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kreuter J, Shamenkov D, Petrov V, et al. Apolipoprotein-mediated transport of nanoparticle-bound drugs across the blood-brain barrier. J Drug Target. 2002;10(4):317–325. doi: 10.1080/10611860290031877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu J, Wang C, Sun J, Xue Y. Neurotoxicity of silica nanoparticles: brain localization and dopaminergic neurons damage pathways. ACS Nano. 2011;5(6):4476–4489. doi: 10.1021/nn103530b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nabeshi H, Yoshikawa T, Matsuyama K, et al. Systemic distribution, nuclear entry and cytotoxicity of amorphous nanosilica following topical application. Biomaterials. 2011;32(11):2713–2724. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deng ZJ, Liang M, Monteiro M, Toth I, Minchin RF. Nanoparticle-induced unfolding of fibrinogen promotes Mac-1 receptor activation and inflammation. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6(1):39–44. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salvador-Morales C, Flahaut E, Sim E, Sloan J, Green ML, Sim RB. Complement activation and protein adsorption by carbon nanotubes. Mol Immunol. 2006;43(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE. Immunological properties of engineered nanomaterials. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2(8):469–478. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dobrovolskaia MA, Clogston JD, Neun BW, Hall JB, Patri AK, McNeil SE. Method for analysis of nanoparticle hemolytic properties in vitro. Nano Lett. 2008;8(8):2180–2187. doi: 10.1021/nl0805615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson-Lyles DN, Peifley K, Lockett S, et al. Fullerenol cytotoxicity in kidney cells is associated with cytoskeleton disruption, autophagic vacuole accumulation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;248(3):249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nel AE, Madler L, Velegol D, et al. Understanding biophysicochemical interactions at the nano-bio interface. Nat Mater. 2009;8(7):543–557. doi: 10.1038/nmat2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]