A 67-year-old man with painless jaundice for 3 weeks was brought to the emergency department by his brother. The patient noted yellow eyes and skin, white stool, fatigue, and pruritis that interfered with sleep. He denied abdominal pain, fevers, chills, diarrhea, melena, hematochezia, anorexia, dysphagia, nausea, or vomiting. He had noted a 20-lb unintentional weight loss over the last 2 months. His past medical history was notable for a stab wound in his abdomen for which he had undergone laparotomy without bowel resection many years ago. He took no medications. He was a Japanese-American Vietnam War veteran who lived with his ex-wife and owned a video store. He had previously drunk 12 beers daily, but cut back to 2 daily 1 year ago. He had a 50 pack-year smoking history and denied any illicit drug use. His family history was negative for malignancy or liver disease.

In a middle-aged patient, painless jaundice is an ominous finding as it immediately brings to mind biliary obstruction due to cholangiocarcinoma or pancreatic head cancer. He had several risk factors for pancreatic cancer, including a significant smoking history and ongoing alcohol consumption. Similarly, the weight loss and lack of right upper quadrant discomfort pointed us toward a process causing extrabiliary obstruction, which is most commonly associated with cancer. Extraductal biliary obstruction usually presents without pain as it does not cause spasm of the sphincter of Oddi as occurs in intraductal processes such as impacted gallstones. Before prematurely deciding about this possibility, however, there are other diagnoses to consider that could be intra- or extrahepatic. These etiologies are difficult to determine until we see the results of laboratory tests including the fractionated bilirubin level. It was also necessary to keep an open mind to the possibility of rare infections that I am less familiar with, contracted during his remote travels in Vietnam, that could cause biliary stasis.

The first step in reasoning is defining a problem representation—the epidemiology, time course, and clinical syndrome—around which a clinician's thinking can be organized. In this case, the physician begins by extracting “painless jaundice” from all the information presented. It is important to seek symptoms or findings that limit the differential diagnosis. After forming the problem representation, the physician activates illness scripts for the various causes of painless jaundice. Illness scripts are the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical features that summarize a clinical diagnosis. As the physician gathers more information, he or she will compare these scripts with particular attention to the data that distinguish among them to determine the most likely diagnosis. The physician recognizes the risk of premature closure, the most common cause of cognitive errors, and entertains other diagnoses.1 The physician is also aware of the limits of his or her knowledge and questions whether the patient’s travel to Vietnam could have resulted in an infectious process unknown to him or her.

The physical examination was notable for a temperature of 98.1° F, blood pressure of 135/82 mmHg, pulse of 82 beats/min, an oxygen saturation of 98 % on ambient air, and a body mass index of 23. The patient was a slender male in no acute distress with jaundice of the skin and soft palate. His cardiopulmonary examination was normal. His abdomen was notable for a large surgical scar, no organomegaly, a possible fluid wave, and multiple skin excoriations. He had no other stigmata of chronic liver disease and no asterixis on neurological examination. Initial laboratory tests demonstrated a normal complete blood count, serum electrolytes, and renal function and coagulation studies. Liver function tests (LFTs) demonstrated a total bilirubin of 13.7 mg/dl with a direct bilirubin of 7.9 mg/dl, an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 50 u/l, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 78 u/l, and albumin of 3.7 g/dl. The hepatitis A and B serologies indicated prior vaccination or infection, and hepatitis C antibodies were negative. The alpha-fetoprotein level was normal.

This patient is an elderly smoker with a subacute process leading to weight loss and painless jaundice. He has several pertinent negatives on his examination and laboratory tests confirming that he does not have one of three life-threatening causes of jaundice: intravascular hemolysis, cholangitis, or fulminant hepatic failure. He has no stigmata of liver disease except for a fluid wave, which is listed as “possible.” Fluid waves are often difficult to determine on examination, so this isolated abdominal finding is tricky to interpret. His LFTs demonstrate a marked conjugated hyperbilirubinemia with fairly trivial changes in his transaminase levels as well as intact synthetic function. This LFT pattern is most consistent with post-sinusoidal biliary obstruction, which greatly reduces the likelihood of intrahepatic processes. Pancreatobiliary cancer is still the most likely diagnosis, but portal lymphadenopathy from lymphoma, tuberculosis, or metastatic disease could cause this picture as well. Cholangiopathy from infectious causes (including HIV, clonorchis sinensis, or ascaraisis), post-surgical adhesions from the previous laparotomy, other mechanical obstructions from Mirizzi’s syndrome, or primary biliary cirrhosis (much more common in women) could conceivably present like this as well. I would obtain HIV testing, a lipase level, and blood cultures, but since my biggest concern is extrahepatic cholestasis, I would quickly move toward an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast to ensure adequate visualization of the pancreas and distal biliary tree, which are not routinely well visualized on ultrasound.

The physician refines the problem representation, noting the patient’s age and smoking history, subacute, progressive time course, and the clinical syndrome, identifying painless jaundice and weight loss. After ruling out life-threatening causes, the physician can use data to narrow the differential diagnosis, in this case beginning with painless jaundice and moving step-wise through the various etiologies of painless jaundice to focus on extrahepatic causes of biliary obstruction. Now the physician can compare the illness scripts for this narrowed problem representation to find the closest match, ultimately considering pancreatobiliary cancer the most likely cause while acknowledging several other causes of biliary obstruction. The physician then decides on the optimal imaging to distinguish among the narrowed list of illness scripts.

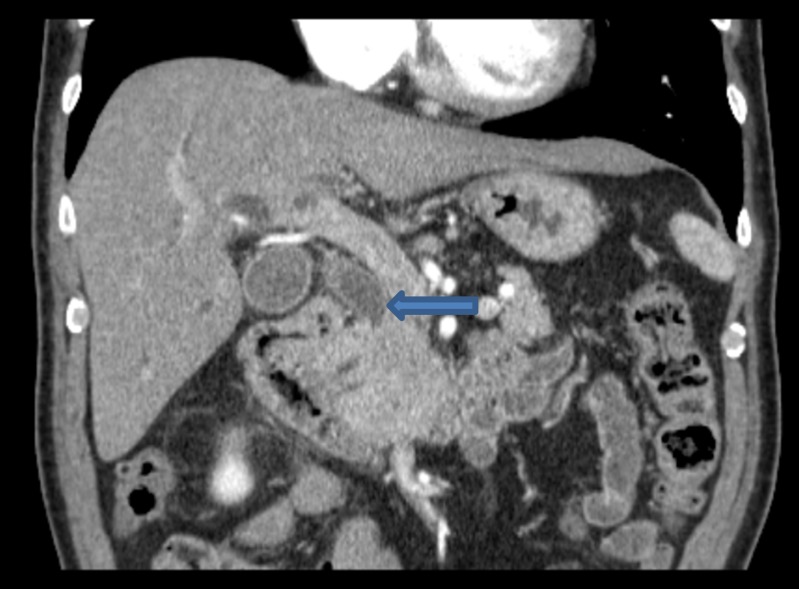

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast (Fig. 1) showed marked intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary dilation with abrupt tapering of the common bile duct (CBD) in the region of the pancreatic head. While a discrete pancreatic lesion was not appreciated, an ampullary lesion could not be entirely excluded. In addition to a pancreatic or ampullary lesion, the radiographic differential diagnosis also included chronic stricture of the CBD versus a small impacted isodense stone.

Figure 1.

Initial CT scan demonstrating tapering of the common bile duct at the head of the pancreas (arrow)

The lack of visualization of a mass gave me pause as I expected to be able to visualize a pancreatic cancer. This does not rule out pancreatic malignancy, which remained the leading possibility in my mind because of the abrupt tapering of the common bile duct. We need more imaging and a cellular diagnosis so I will consult the gastroenterology and general surgery service for assistance with the diagnosis and management. Since the biggest concern is pruritis, we should provide symptomatic treatment.

The physician pauses when the anticipated finding that would support the leading diagnosis is not found on the CT scan and appropriately steps back to avoid anchoring. In clinical medicine, anchoring is a cognitive bias that describes a physician’s tendency to ignore test results that diverge from his or her initial hypothesis.

Two days later, the patient underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which revealed a single, localized, 1-cm stenosis of the common bile duct that was successfully stented. Given the patient’s history of alcoholism, biliary stricture in the setting of chronic pancreatitis was also considered. An endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with fine-needle aspiration (FNA) demonstrated a 2.3 × 2.8-cm mass in the uncinate process of the pancreas without vascular invasion. The patient tolerated the procedures well and was treated with hydroxyzine and Sarna lotion for his pruritis.

The finding of a mass in the head of the pancreas is what we had originally feared. The pretest probability of pancreatic cancer was at least 70 % according to my previous clinical experience with patients with this presentation and tapering of the CBD on CT scan. Visualization of a mass on EUS increased the posttest probability to at least 90 % for pancreatic cancer, and the biopsy performed to confirm the diagnosis was helpful. Further evaluation should include a staging workup, and the patient should be considered for a pancreato-duodenectomy (Whipple procedure) with an eye toward cure if he has localized disease. Unfortunately, only a minority of patients with pancreatic cancer are eligible for surgery at the time of diagnosis; it tends to be patients who have adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas, which causes painless jaundice.

The physician intuitively applies Bayes’ theorem by establishing a pretest probability of 70 %, which increases to a posttest probability of 90 % after EUS has demonstrated a mass.

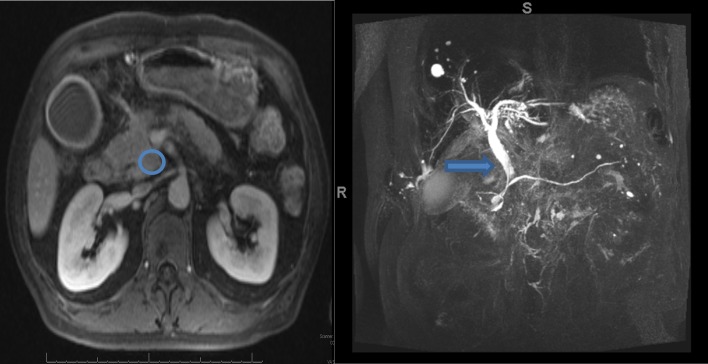

While awaiting the pathology results, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and liver protocol magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 2) demonstrated a 2.7 × 1.7-cm uncinate process mass as well as intra- and extrahepatic biliary dilatation without pancreatic ductal dilatation. The FNA biopsy results returned “abundant benign pancreatic elements.” The CA 19-9 level was within the normal range. The patient was discharged home for follow-up at a surgical clinic 3 days after discharge.

Figure 2.

Liver protocol magnetic resonance imaging (left) demonstrated a 2.7 × 1.7-cm uncinate process mass, consistent with malignancy (circle). A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (right) demonstrated intra- and extrahepatic biliary dilatation without pancreatic ductal dilatation (arrow)

Although no diagnostic procedure is perfect, the FNA result was surprising as I would have expected a positive result. A Whipple procedure entails at least a 3 % operative mortality, prolonged postoperative recovery, and the need for lifelong pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy. Therefore, it is critical to be certain of a cancer diagnosis before subjecting the patient to such a morbid procedure. Since these results are unexpected, I would slow down and use Bayes’ theorem to help me understand how these test results would alter my pretest probability of 90 %. Therefore, I need to calculate the negative likelihood ratios for each of these tests to determine whether the patient should undergo a Whipple procedure or undergo further diagnostic testing.

To do this, I need the test characteristics of the ERCP FNA and CA 19-9, which make the calculation quite easy. The test characteristics can generally be obtained quickly from online reference materials. Mathematically, a negative likelihood ratio (nLR) is equal to: (1-Sensitivity)/Specificity. For CA 19-9, the range of sensitivity (Sn) and specificity (Sp) from the literature are 70–92 %. For ease of calculation, I will assume mid-range values of 80% for both Sn and Sp; thus, the nLR = (1–0.8)/0.8 = 0.25. From there, I use a shortcut table of interpretation of likelihood ratios to help me calculate the posttest probability (Table 1). From this table, I see that the posttest probability is reduced by approximately 30 % for an nLR of 0.25. Now my new posttest probability of cancer after a negative CA 19-9 is 60 % (90 % pretest - 30 % posttest).

Table 1.

Likelihood ratios and bedside estimates

| Likelihood ratio | Approximate change in probability (%) |

|---|---|

| Values between 0 and 1 decrease the posttest probability of disease | |

| 0.1 | −45 |

| 0.2 | −30 |

| 0.3 | −25 |

| 0.4 | −20 |

| 0.5 | −15 |

| 1.0 | 0 |

| Values greater than 1 increase the posttest probability of disease | |

| 2 | 15 |

| 3 | 20 |

| 4 | 25 |

| 5 | 30 |

| 6 | 35 |

| 7 | |

| 8 | 40 |

| 9 | |

| 10 | 45 |

How to use likelihood ratios to estimate pre- to posttest probability changes based on test results. Adapted from: McGee S. Simplifying likelihood ratios. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(8):647–650

When applying sequential tests, the posttest probability after the first test result will become the pretest probability for the subsequent test result. Now we can examine the negative results of the ERCP FNA. Sn and Sp for FNA biopsy are 90 % each. Thus, the nLR, (1–0.9)/0.9, is 0.11. From Table 1, we see that this further reduces the posttest probability by 45 %. This leaves us with a 15 % posttest probability of cancer (60 % pretest – 45 % posttest), which puts this diagnosis significantly in doubt. This would lead me to revisit the problem representation and differential diagnosis and suggest further testing such as repeat tissue biopsy prior to surgical intervention.

The physician recognizes that the results do not fit the initial hypothesis, and this triggers slowing down and moving to system 2 (analytic reasoning) by applying Bayes’ theorem explicitly as more data are acquired. The physician’s pretest probability based on all data prior to the FNA and CA 19-9 was 90 %; after the negative results from the last two tests, the clinician’s posttest probability decreases to 15 %, causing a reconsideration of the initial diagnosis and avoidance of the anchoring heuristic. Bayes’ theorem is one method of analytic, or system 2, thinking that can be applied in clinical medicine when illness scripts do not fit with the “working” patient’s problem representation.

The patient was seen in a general surgery clinic where all imaging, pathology, and laboratory results were thoroughly reviewed. A pylorus-preserving Whipple resection was planned for suspected distal cholangiocarcinoma or an ampullary tumor, and the patient underwent surgery 2 days later. Intraoperatively, a very firm, periampullary lesion was identified and resected. Additionally, palpable liver nodules were resected to rule out metastatic lesions. The operation was uncomplicated. The surgical pathology showed duct-centered lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, ductilitis, fibrosis, and phlebitis with more than 100 IgG4 plasma cells per high power field, consistent with autoimmune pancreatitis type I or IgG4-related sclerosing pancreatitis and cholangitis (Fig. 3). The serum IgG4 level was 259 mg/dl (normal range, 4 to 89 mg/dl).

Figure 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain at low power (left) showed extensive duct-centered lymphoplasmacytic inflammation (arrows). Immunohistochemical staining for IgG4 at high power (right) revealed more than 100 IgG4-positive plasma cells per high power field (arrows)

In retrospect, we should have obtained a confirmatory biopsy and the IgG4 levels prior to surgical intervention. I remember many years ago talking about Whipple’s procedures with a surgical colleague, who was willing to tolerate a 10 % rate of negative pathology results post-Whipple procedure to be sure not to miss pancreatic cancer. Perhaps IgG4 disease was a contributor to these negative results. I did not consider IgG4 disease because I lacked a well-built illness script for this condition. As physicians it is important for us to learn from our successes as well as our failures. In the future, I will include a pancreatic mass in my illness script for IgG4 disease. If we had been unable to obtain a cytological diagnosis after another biopsy attempt, I think I would still have eventually wanted the patient to undergo a surgical resection to ensure we did not miss a diagnosis that has very high mortality if left untreated.

The patient was informed about the lack of cancer on pathology and was thrilled that he did not have cancer. He was subsequently referred to rheumatology and started on steroid therapy for his IgG4 disease. The patient is doing well 1 year post-Whipple procedure.

Discussion

This case demonstrates the clinical applicability of Bayes’ theorem. When patients do not fit neatly into an illness script, it may be necessary to slow down and apply quantitative analytics to reduce the diagnostic error. In this case, knowing when to switch from implicit reasoning (system 1) to a more deliberate system 2 approach (the dual process theory) could have prevented an unnecessary procedure.2 Bayes’ theorem is one method for quantifying our clinical reasoning and diagnostic certainty that could have had significant clinical implications had it been applied earlier in this case, i.e., by pausing after the negative biopsy and re-exploring the potential diagnoses for a pancreatic mass. In actual practice, physicians are far more likely to refine their probability of disease based on a gut feeling of the importance of a clinical finding or test result as opposed to explicitly using Bayes’ theorem. While this clinical gestalt is often enough sufficient for making the right decision for a patient, in cases with significant diagnostic confusion, Bayes’ theorem can be invaluable.

We speculate that the major barrier to utilizing Bayes’ theorem is its relative inefficiency in day-to-day practice. The huge number of clinical decisions physicians face daily makes the frequent application of Bayes’ theorem impractical. Heuristics or mental short cuts, despite associated cognitive biases, are more efficient, and possibly more effective, than analytical reasoning in the majority of problems encountered by physicians.3 However, as evident in this case, it is important for physicians to know when to pause and use Bayes’ theorem explicitly to refine their diagnostic reasoning.

Other barriers to applying Bayes’ theorem may include the lack of formal teaching or role modeling in analytical reasoning, difficulty accessing test characteristics, and unfamiliarity with how or when to apply it. Medical students have limited clinical exposure when analytic reasoning is described in the pre-clinical years, and most clinicians do not routinely apply Bayes’ theorem in everyday practice, leaving trainees with little exposure to the clinical application of the methods described here. Further, to use Bayes’ theorem appropriately, one must be able to assign a pretest probability and know the test characteristics, both of which may require additional research by the clinician. Finally, providers are often unfamiliar with the techniques described here, in which case they may be more likely to rely on their clinical gestalt in cases where analytical techniques could be particularly useful. Yet all of these barriers can be overcome with application of and practice using this important clinical decision-making technique.

To utilize Bayes’ theorem efficiently, smart phone applications (e.g., MedCalPro’s “posttest probability”) or simple reference tables (see Table 1) are available.4 Note that there are limitations to these simplified methods, however, and Bayes’ theorem should be used to update posttest probabilities as test results become available. This enables the clinician to work sequentially to reach appropriate diagnostic certainty.

Clinical Teaching Points

The differential diagnosis for a solid pancreatic mass includes pancreatic adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumor/carcinoma, metastatic carcinoma, lymphoma, focal chronic pancreatitis, and IgG4-related autoimmune pancreatitis.

IgG4-related autoimmune pancreatitis is more prevalent in older men (58 to 69 years of age).5 The pathogenesis is unclear but likely involves an autoimmune component, and the role of the IgG4 antibody is not understood.

The most common presentation of IgG4-related autoimmune pancreatitis is obstructive jaundice secondary to a pancreatic mass, which may be confused with carcinoma or lymphoma.

In the USA, the “HISORt” criteria are used to diagnose IgG4-related autoimmune pancreatitis: histology, characteristic imaging findings on CT and/or pancreatography, elevated serum IgG4 levels on serological testing, other organ involvement, and response of pancreatic and extrapancreatic manifestations to glucocorticoid therapy.6

The majority of patients show a significant clinical response within 2 weeks of glucocorticoid treatment.7

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Lawrence M. Tierney, Jr., for providing insights while solving this case, as an unknown clinical problem-solving exercise, during a resident report session. We would also like to thank Dr. Gurpreet Dhaliwal for his suggestions for the first draft of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Graber ML. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Int Med. 2005;165:1493–1499. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.13.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vick A, Kraemer RR, Morris JL, Willett LL, Centor RM, Estrada CA, Rodriguez JM. A 60-year-old woman with chorea and weight loss. J Gen Intern Med. June;27(6):747–751. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1928-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhaliwal G. Going with your gut. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;26(2):107–109. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1578-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGee S. Simplifying likelihood ratios. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(8):647–650. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zen Y, Nakanuma Y. IgG4-related disease: a cross-sectional study of 114 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1812. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f7266b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Takahashi N, Zhang L, Clain JE, Pearson RK, Petersen BT, Vege SS, Farnell MB. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis: the Mayo Clinic experience. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(8):1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moon SH, Kim MH, Park DH, et al. Is a 2-week steroid trial after initial negative investigation for malignancy useful in differentiating autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer? A prospective outcome study. Gut. 2008;57:1704. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.150979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]