Abstract

Objectives

(1)To describe the prevalence and severity of tremor in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) registered within a large North American MS registry; (2) to provide detailed descriptions on the characteristics and severity of tremor in a subset of registrants and (3) to compare several measures of tremor severity for strength of agreement.

Setting

The North American Research Committee on MS (NARCOMS) registry.

Participants

Registrants of NARCOMS reporting mild or greater tremor severity.

Outcome measures

We determined the cross-sectional prevalence of tremor in the NARCOMS registry over three semiannual updates between fall 2010 and fall 2011. A subset of registrants (n=552) completed a supplemental survey providing detailed descriptions of their tremor. Outcomes included descriptive characteristics of their tremors and correlations between outcome measures to determine the strength of agreement in assessing tremor severity.

Results

The estimated prevalence of tremor in NARCOMS ranged from 45% to 46.8%, with severe tremor affecting 5.5–5.9% of respondents. In the subset completing the supplemental survey, mild tremor severity was associated with younger age of MS diagnosis and tremor onset than those with moderate or severe tremor. However, tremor severity did not differ by duration of disease or tremor. Respondents provided descriptions of tremor symptoms on the Clinical Ataxia Rating Scale, which had a moderate to good (ρ=0.595) correlation with the Tremor Related Activities of Daily Living (TRADL) scale. Objectively scored Archimedes’ spirals had a weaker (ρ=0.358) correlation with the TRADL. Rates of unemployment, disability and symptomatic medication use increased with tremor severity, but were high even among those with mild tremor.

Conclusions

Tremor is common among NARCOMS registrants and severely disabling for some. Both ADL-based and symptom-descriptive measures of tremor severity can be used to stratify patients.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This cohort represents the largest descriptive study of multiple sclerosis (MS)-associated tremor to date.

The data presented are mostly derived from patient-reported scales, which have been used in previous descriptive studies of MS tremor.

Results of the study could not be objectively validated; however, findings are similar to previous descriptive studies which did include objective validation.

These data reinforce previous smaller studies describing the disproportionate effect of tremor on employment, function and overall quality of life for patients affected with MS.

Background

Associated with multiple sclerosis (MS) since the earliest descriptions of the disease, tremor is noteworthy for its strong association with disability1 and resistance to symptomatic treatment.2 The exact prevalence of tremor in the MS population is unknown; however, estimates from two prior studies suggest a prevalence range of 25–60%, with severe tremor in 3–15% of patients.3 4 Yet, the modest size of these studies (100 and 200 patients) and the populations they describe (a clinic-based cohort, and a community-based cohort with overall mild disease course5) allows for the possibility that their prevalence estimates might not generalise to the wider MS population.

A major challenge to accurately estimating the prevalence and severity of MS tremor arises from the difficulty in obtaining a large, representative cross-section of the MS population. The North American Research Committee on MS (NARCOMS) registry is a unique resource, containing over 36000 participants with MS, of whom more than 13 000 submit semiannual updates on various aspects of their disease,6 including the NARCOMS Tremor and Coordination Scale (TACS), which has been validated against clinically assessed measures of tremor.7 The size of the NARCOMS registry allows for the identification of large subsets of patients with less common manifestations, such as severe tremor.

This work represents the largest descriptive study of tremor in MS to date, estimating its prevalence and severity in the NARCOMS registry and providing a detailed, patient-reported summary of the effects of tremor on daily function and quality of life (QOL). While there is no gold standard for the measurement of tremor severity in patients with MS, better normative data about how tremor severity relates to QOL in patients with MS could be applied in trial design for potential therapeutic interventions.

Methods

Tremor prevalence

NARCOMS distributes semiannual surveys to all of its registered members asking a wide range of MS-related and QOL-related questions. Tremor and ataxia are assessed in these surveys by the TACS, which has been shown to have construct and criterion validity.7 On the scale, respondents score their tremor severity from 0 to 5 indicating absent, minimal, mild, moderate, severe or totally disabling tremor. Minimal indicates the presence of tremor without functional impairment, while the other levels indicate increasing impact of tremor on function.

In order to estimate tremor prevalence within NARCOMS, any TACS score of 1 or greater was counted towards the tremor prevalence. To approximate the methods used in prior prevalence studies of MS tremor, the prevalence of severe tremor (including totally disabling tremor) was also determined.

Surveyed cohort

With prior approval from the local IRB, we designed a supplemental printed survey that was mailed to a subset of NARCOMS registrants who were using MS disease modifying drugs (DMDs) and who indicated at least a mild effect of tremor on function on a NARCOMS update. While some demographic information and details of respondents’ MS was extracted from the master NARCOMS data set, the survey requested additional information specific to the experience of tremor, including handedness, distribution of tremor in the body, duration and family history of tremor, use of symptomatic medications to suppress tremor, and several scales designed to assess tremor severity (table 1). As part of the tremor severity assessments, respondents also drew Archimedes’ spirals with each hand using a pen provided with the survey. The pens were provided to minimise variability between respondents that might be introduced by differing writing instruments. Respondents were also asked to indicate current use of DMDs.

Table 1.

Instruments used in the study

| Name | Items (n) | Score range | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tremor and Coordination Scale | 1 | 0–5 | Brief description of tremor severity and impact on daily function |

| Tremor Related Activities of Daily Living | 25 | 25–100 | Activity of daily living-focused questions on impairment caused by MS tremor |

| Visual analog scale | 1 | 1–10 | Overall quality of life measure |

| Clinical Ataxia Rating Scale | 4 | 0–16 | Descriptive characteristics of tremor not linked to function or daily activity |

| Archimedes’ spirals | 2 | 0–20 | Right-handed and left-handed Archimedes’ spirals, scored by blinded raters |

| Tremor-related handicaps | 9 | Categorical/unranked responses | Physical or emotional impact of tremor on participation in a range of activities |

| Patient Determined Disease Steps | 1 | 0–8 | Ordinal scale indicating overall MS disability ranging from normal to bedridden. Surrogate of Expanded Disability Status Scale. |

MS, multiple sclerosis.

Each of the questionnaires listed in table 1 has been previously utilised in studies of MS-related tremor.4 7–10 Only the Clinical Ataxia Rating Scale (CARS) was used out of its original context: the CARS is intended for use by clinicians to objectively score overall tremor severity through a ranked scoring system to describe dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia and gait impairment. For the purposes of this study, the language for the CARS was altered to be made understandable to non-clinicians, so that respondents could report ataxic symptoms in a descriptive manner approximating a clinical evaluation.

Patients who received the survey were invited to participate as part of a separate study evaluating whether DMDs change tremor severity over time.11 At a minimum, all patients must have indicated a mild or worse tremor between fall 2010 and 2011, and the current use of an approved MS DMD. Respondents taking natalizumab were deliberately oversampled, while patients taking the other approved MS DMDs were selected at random.

Surveys were mailed in March 2012 and returned over a 2-month period. Data from the supplemental survey and the 2011 semiannual surveys (demographics, MS-related disability and QOL) were compiled and de-identified. MS disability in NARCOMS is scored using the Patient Determined Disease Steps (PDDS),12 and general health-related QOL is gauged by the Short Form (SF)-12 physical and mental composite scores.13

Archimedes’ spirals were scored by three raters (two primary, one secondary) with experience in the treatment of movement disorders. Each Archimedes spiral was assigned a score between 0 and 10, with 0 representing no evidence of tremor and 10 indicating inability to complete the spiral. Scores were assigned according to a scoring system published by Bain and Alusi.8 When the primary reviewer scores were identical or differed by 1 point, a mean of the two primary reviewer scores were used for that spiral. When scores differed by >1 point, the secondary reviewer's score was incorporated into the mean score. A subset of spirals were duplicated and randomly distributed within the scored spirals to test intra-rater reliability. Each respondent's left-handed and right-handed mean spiral scores were summed to generate a sum spiral score which was used for analysis. In order to account for spiral differences related to handedness, respondents were asked in the survey to self-identify their dominant hand.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was conducted using JMP 10.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA). To determine the prevalence of tremor in the NARCOMS registry, we calculated the proportion of patients indicating a TACS score >0 relative to the total number of completed surveys across three consecutive semiannual survey periods: fall 2010, spring 2011 and fall 2011 (the ‘Tremor Prevalence Cohort’). Three periods were included in order to maximise the number of eligible respondents to whom we could send the paper tremor survey, which then defined the ‘Surveyed Cohort’.

The cohort was stratified by tremor severity as measured by the TACS, as this scale alone is used to identify tremor on the semiannual NARCOMS updates distributed to active participants. Owing to the small number of respondents indicating totally disabling tremor on the TACS, these respondents were combined with those reporting severe tremor for the purpose of determining severe tremor prevalence.

Descriptive characteristics of the cohort were reported as frequencies, means with SDs, or medians with IQRs. Comparisons between groups were performed using analysis of variance for continuous outcomes (eg, age), and χ2 tests were used to compare nominal data (eg, sex). Intra-rater and inter-rater reliability of the spiral ratings were determined by calculating κ scores and Spearman correlations for the three raters.

Spearman's correlations were calculated for the various tremor and disease severity scales, to determine strength of agreement. Missing data were handled through listwise deletion.

Results

Tremor prevalence

The mean prevalence of tremor among NARCOMS respondents was approximately 45% for each of the three update periods (the ‘Tremor Prevalence Cohort’, table 2). Approximately one quarter of respondents experienced tremor with at least some impact on function (mild or worse tremor). In table 3, the NARCOMS Prevalence Cohort is compared to the London, UK4 and Olmsted County, USA3 prevalence studies on MS tremor.

Table 2.

Prevalence of tremor in the NARCOMS registry

| Fall 2010 | Spring 2011 | Fall 2011 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed surveys (n) | 14 268 | 14 235 | 13 117 |

| TACS≥1, n (%) (any tremor) | 6424 (45.0) | 6655 (46.8) | 5923 (45.2) |

| TACS≥2, n (%) (mild or worse tremor) | 3453 (24.2) | 3604 (25.3) | 3155 (24.1) |

| TACS≥3, n (%) (moderate or worse tremor) | 1978 (13.9) | 1955 (13.7) | 1760 (13.4) |

| TACS≥4, n (%) (severe or worse tremor) | 848 (5.9) | 789 (5.5) | 757 (5.8) |

| TACS=5, n (%) (totally disabling tremor) | 212 (1.5) | 202 (1.4) | 162 (1.2) |

NARCOMS, North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis; TACS, Tremor and Coordination Scale.

Table 3.

Tremor prevalence across studies

| London, UK | Olmsted County, USA | NARCOMS registry* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort size, n | 100 | 200 | 13 873 |

| Tremor prevalence, % | 37.0 (58.0)† | 25.5 | 45.7 |

| Severe tremor prevalence, % | 15.0 | 3.0 | 5.8 |

*Mean results from Fall 2010, Spring 2011 and Fall 2011 surveys.

†Tremor was reported by 37 patients, but detected by examining clinicians in 58.

NARCOMS, North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis.

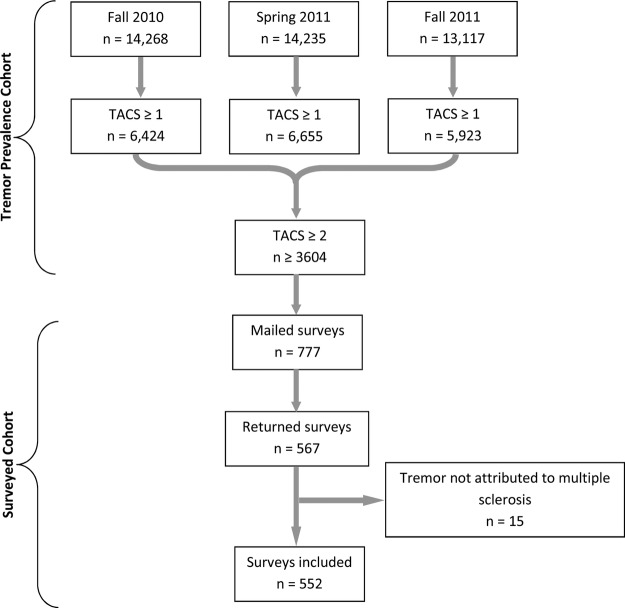

Among the approximately 3600 NARCOMS respondents with functionally significant tremor (TACS≥2), 777 were mailed supplemental surveys, and of those returned, 552 were included in the final database (the ‘Surveyed Cohort’, figure 1). The Surveyed Cohort constitutes approximately 16% of NARCOMS registrants with mild or worse tremor. Respondents who completed the survey and attributed their tremor entirely to a cause other than MS (2.7% of respondents) were excluded from the final data set.

Figure 1.

Recruitment flowchart. The upper bracket depicts how tremor prevalence was determined for the NARCOMS registry over three consecutive semi-annual surveys in fall 2010, spring 2011 and fall 2011. The lower bracket depicts the derivation of the Surveyed Cohort from those registrants with mild or worse tremor who were mailed the supplemental survey. NARCOMS, North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis; TACS, Tremor and Coordination Scale.

The distribution of tremor severity within the Surveyed Cohort differed somewhat from the Tremor Prevalence Cohort. Respondents in the Surveyed Cohort were less likely to characterise their tremor as mild (35.5% vs 42.7–45.8%), and somewhat more likely to identify themselves as having moderate (38% vs 31.8–32.7%) or severe (22.8% vs 16.3–18.9%) tremor. The ranges presented for the Prevalence Cohort derive from the three separate survey periods. PDDS scores, reflecting global MS disability, were the same by TACS level between the Prevalence and Surveyed Cohorts (data not shown).

Demographics and distribution of tremor

Demographic characteristics of the Surveyed Cohort are reported in table 4. Women comprised a greater proportion of those with mild tremor, while men were more likely to report severe or totally disabling tremor. Tremor severity did not differ between white and non-white respondents; however, NARCOMS is known to under-represent minority ethnic groups.14 Current age, MS onset age and tremor onset age all differed between TACS severity groups; however, neither duration of tremor nor duration of MS were significantly different between tremor severity groups.

Table 4.

Demographics and descriptive characteristics

| Characteristic | Total cohort (n=550) | TACS=2 (n=196) | TACS=3 (n=209) | TACS=4 or 5 (n=145) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | 0.004* | ||||

| Female | 429 (78.0) | 162 (82.7) | 168 (80.4) | 99 (68.3) | |

| Male | 121 (22.0) | 34 (17.3) | 41 (19.6) | 46 (31.7) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.821 | ||||

| White | 485 (96.0) | 175 (95.6) | 179 (96.8) | 131 (95.6) | |

| Non-white | 20 (4.0) | 8 (4.4) | 6 (3.2) | 6 (4.4) | |

| MS subtype, n (%) | 0.005* | ||||

| Relapsing–remitting | 230 (48.9) | 102 (59.3) | 80 (47.3) | 48 (36.9) | |

| 2° Progressive | 145 (30.8) | 48 (27.9) | 50 (29.6) | 47 (36.2) | |

| 1° Progressive | 27 (5.7) | 5 (2.9) | 8 (4.7) | 14 (10.7) | |

| Progressive-relapsing | 30 (6.4) | 6 (3.5) | 14 (8.3) | 10 (7.7) | |

| Unsure | 33 (7.0) | 11 (6.4) | 13 (7.7) | 9 (6.9) | |

| Current age, mean (SD) | 55.3 (9.2) | 53.4 (9.6) | 56.0 (9.1) | 57.0 (8.4) | <0.001* |

| Age of MS diagnosis, mean (SD) | 38.1 (9.5) | 36.6 (9.4) | 39.2 (9.6) | 38.7 (9.3) | 0.018* |

| Age of tremor onset, mean (SD) | 43.6 (11.4) | 41.8 (11.6) | 44.4 (11.0) | 45.0 (11.3) | 0.021* |

| Duration of MS, mean (SD) | 17.1 (8.4) | 16.7 (8.2) | 16.8 (7.9) | 18.3 (9.2) | 0.146 |

| Duration of tremor, mean (SD) | 11.6 (8.8) | 11.2 (8.3) | 11.6 (8.9) | 12.1 (9.5) | 0.702 |

| Family history of tremor, n (%) | 84 (15.5) | 30 (15.7) | 34 (16.4) | 20 (14.1) | 0.845 |

| Patient Determined Disease Step (IQR) | 5 (3, 6) | 4 (2, 5) | 5 (3, 6) | 6 (4, 6) | <0.001* |

*p<0.05.

MS, multiple sclerosis; TACS, Tremor and Coordination Scale.

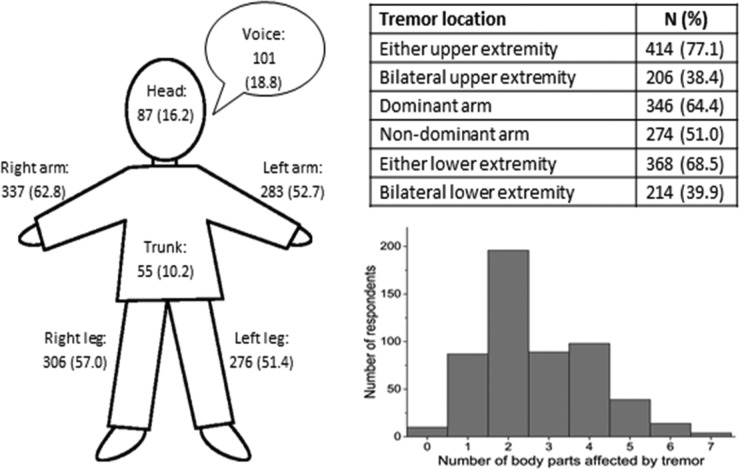

Figure 2 summarises the patient-reported descriptions of body regions affected by tremor. Similar to previous reports3 4 the upper extremities were most commonly involved, and among those who reported unilateral tremor (n=208), respondents were twice as likely to report tremor in their dominant arm (n=140, 67.3%) as compared with their non-dominant arm (n=68, 32.7%).

Figure 2.

Bodily distribution of tremor among surveyed registrants. The figure depicts the number (%) of patients reporting tremor in each of 7 bodily regions. The table reports the proportion of respondents indicating tremor in either or both upper or lower extremities, and the occurrence of tremor in the dominant versus non-dominant arm. The histogram depicts how the tremor was distributed throughout the body for respondents with at least mild tremor.

Tremor severity measures

Both subjective and objective instruments have been developed to measure tremor severity. Subjective instruments generally relate tremor severity to QOL and interference with routine activities, while objective instruments rely on direct observation of tremor by a clinician expert or indirect rating of the effects of tremor, such as accelerometers, Archimedes’ spirals or handwriting samples.9 10 At present, there is no widely accepted ‘gold standard’ for assessing tremor severity in MS. As such, we chose to include a range of instruments including QOL-based measures (TACS, Tremor Related Activities of Daily Living (TRADL), SF-12 Health Survey), objectively scored Archimedes’ spirals and the descriptive (but not objective) CARS.

For the scoring of Archimedes’ spirals, κ and Spearman statistics were determined for inter-rater and intra-rater reliability. The κ scores reflect the consistency with which raters assigned identical scores to individual spirals, while the Spearman scores reflect how consistently spirals were ranked in order of severity. Intra-rater κ scores ranged from 0.48 to 0.56 (moderate agreement) and Spearman coefficients ranged from 0.79 to 0.89 (good agreement), while inter-rater κ scores ranged from 0.30 to 0.38 (fair agreement) and Spearman coefficients ranged from 0.81 to 0.85 (good agreement). While the κ scores indicate broad inconsistency in assigning the same score to the same spiral, the Spearman scores suggest good consistency in ranking spirals by order of severity.

The correlation between spiral sum scores and the CARS was weak (ρ=0.288, p<0.001). A summary of the Spearman correlations between the objective/descriptive instruments (spiral scores and CARS) and the subjective/QOL instruments is depicted in table 5. For all of the subjective QOL measures the correlation with the CARS was stronger than with spirography scores. The strongest correlation was between the CARS and the TRADL. The strength of this correlation between ADL impairments and specific abnormalities in body movement suggests patient-provided descriptions of tremor (on the CARS) correspond reasonably well to tremor impacts on activities of daily living (the TRADL). Correlations were weakest with the physical SF-12, which is neither MS-specific nor tremor-specific.

Table 5.

Spearman correlations between descriptive and quality of life tremor assessment instruments

| Subjective measures of impairment or quality of life | Objective/descriptive measures of tremor |

|

|---|---|---|

| Spiral Sum Score | Clinical Ataxia Rating Scale | |

| Tremor and Coordination Scale | 0.203 | 0.368 |

| Tremor Related Activities of Daily Living | 0.358 | 0.595 |

| Visual analog scale | 0.246 | 0.485 |

| Patient Determined Disease Steps | 0.312 | 0.534 |

| SF-12 Physical Health QOL | −0.145 | −0.275 |

SF-12, Short Form 12; QOL, quality of life.

In an effort to improve the correlation strength between spirography and TRADL, we limited the correlation to those respondents indicating involvement of the dominant upper extremity. Even using this limited data set, the strength of the correlation only improved to 0.381.

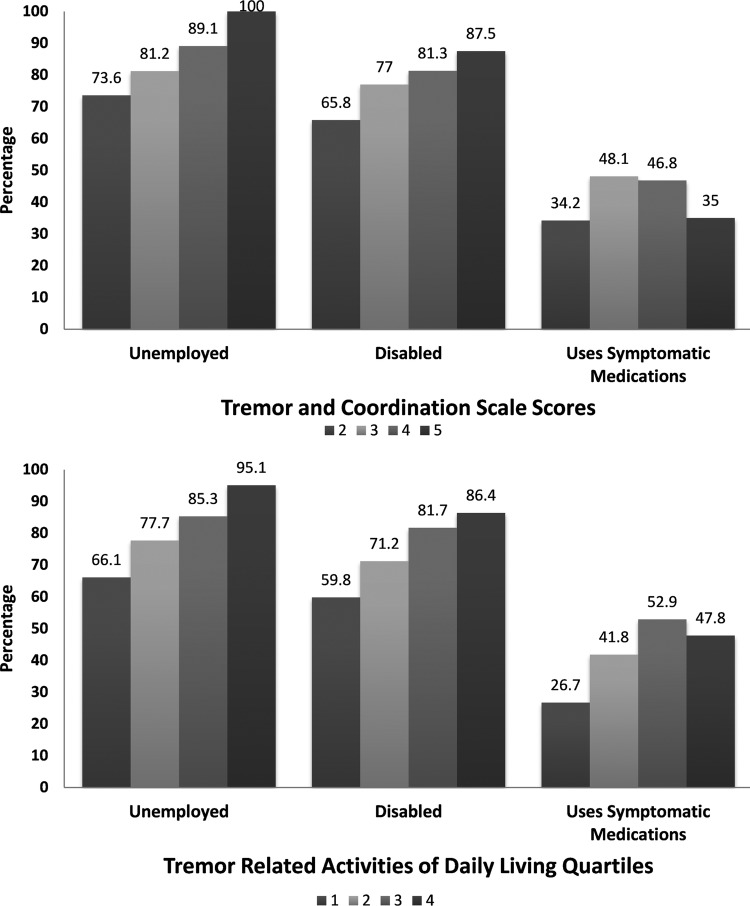

Figure 3 depicts the association between tremor severity and unemployment, disability, and use of symptomatic medications (to suppress tremor severity). The intention was to ‘anchor’ the inherently subjective measures of severity to outcomes less prone to responder opinion. For comparison purposes, we included the TACS (since it is regularly included in NARCOMS updates) and the TRADL (owing to its detailed inventory of tremor-related QOL scenarios). As the level of tremor severity increased, an increasing proportion of those in each TACS level reported being unemployed and disabled. With respect to the use of symptomatic medications, the TRADL quartiles appeared to better correspond with use of tremor-suppressing medications, although the most severely affected patients on both scales appeared less likely to use symptomatic medications.

Figure 3.

Employment, disability and symptomatic medication use by tremor severity. The figure depicts the proportion of registrants indicating unemployment, disability status and use of symptomatic medication by two different measures of tremor severity. The upper figure depicts tremor severity by the Tremor and Coordination Scale (TACS) scores derived from the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) semiannual updates. The scores denote mild (TACS=2), moderate (TACS=3), severe (TACS=4) and totally disabling (TACS=5) tremor. The lower figure depicts tremor severity by dividing responses on the Tremor Related Activities of Daily Living scale into quartiles of severity ranging from 1 (least severe) to 4 (most severe).

Discussion

This study describes the largest cohort of patients with MS-associated tremor to date. In our study, the prevalence of both overall tremor and severe tremor fall between that described in the London clinic-based prevalence study4 and the Olmsted County population-based study.3 By utilising patient-reported data, our study reflects the characteristics of a large, heterogeneous patient population across a wide geographic area. While registry-based studies by nature are limited by the inability to objectively confirm the data being provided, the size of our cohort should alleviate some concerns about whether these results are indicative of the general MS population. Indeed, an advantage to our approach is that we are less prone to the bias towards greater disease severity often encountered in studies based in specialised academic centres, and less prone to the population homogeneity of a single-region population-based study.

Another aim of this study was to introduce an objectively scored measurement of tremor (the Archimedes’ spirals) into an otherwise subjective battery of outcomes. However, the correlation of spirography scores with subjective measures of tremor severity were at best only fair, suggesting the task of drawing spirals does not correspond with daily function. Likewise, drawing spirals would not be expected to capture resting or postural tremors, or tremors affecting parts of the body other than the distal upper extremities. We were also unable to control for patients bracing their drawing hands to improve the spiral quality, although the surveys did include instructions not to do so.

In contrast to the Archimedes’ spirals, the modified CARS, which asked respondents to put themselves in the place of an observant clinician and rate the severity of their tremor based on manoeuvres commonly performed in a neurological examination, yielded the strongest correlations with the tremor-specific (TRADL, TACS, visual analog scale) and the MS-specific (PDDS) disability measures. These results suggest patient-report measures of tremor need not be limited to daily function and QOL-anchored scales, although formal validation would further strengthen this conclusion.

By including multiple measures of tremor severity (eg, TRADL, TACS) we were also able to compare measures of tremor severity to end points such as employment and disability. Despite the limited scoring range of the TACS, it performed similar to the TRADL in stratifying respondents by tremor severity.

Additional interesting observations also bear mentioning. In all three prevalence studies on MS tremor, upper extremity tremor was by far the most common (>90% in London and Olmsted County studies, 77.1% in this study).3 4 In contrast, NARCOMS respondents were much more likely to report tremor in the lower extremities (68.5%) than in either of the two earlier studies (17–24%). The rates of head and truncal tremor were similar across all three studies. Since we know from our results that respondents were more likely to report tremor in a dominant upper extremity than in a non-dominant upper extremity, suggesting a reporting bias, they may likewise misidentify symptoms such as ataxia, clonus or spasticity in the lower extremities as tremor.

This study also found patients with MS with tremor report a high rate of tremor in their family history (15.5%), which was also observed by Bain and Alusi, who reported a rate of 7%.4 In comparison, the most common form of tremor among adults, essential tremor,15 affects approximately 0.9% of the adult population, and between 4.6% and 6.3% of the population older than 65 years.16 Whether this represents a bias towards increased recognition of tremor among affected families versus a biological predisposition towards tremor is unclear.

While our results in large part confirm or expand on prior observations regarding tremor in MS, our study does have limitations. As a registry-based study, our reports of tremor severity and other aspects of patients’ illness cannot be independently verified. However, past validation studies on the NARCOMS registry have largely supported the validity and generalisability of its findings.17–19 Another potential criticism of this study is that participant selection for the Surveyed Cohort was not conducted completely at random. The selection criteria for the cohort were developed to answer a question related to the effects of DMDs on tremor over time, thus all patients who were not using DMDs were excluded, and only those with mild or worse tremor (indicating at least some interference with function) were invited to complete the detailed survey. By limiting the cohort to those patients with functionally relevant tremor, the correlations in this study are weakened by the absence of those patients with absent or very mild tremor. This excluded part of the tremor population also makes the correlations presented in this paper unsuitable for comparison to similar prior studies using the same instruments in a population containing the full range of tremor severity. In addition, since our population oversampled patients taking natalizumab as their DMD, the sample may be biased towards patients with more severe disease, since natalizumab is commonly reserved for those patients with very active or severe MS.

In summary, this study confirms in a large patient registry that tremor is common among patients with MS, and that tremor can markedly detract from patient QOL and daily function. Better understanding the prevalence and severity of tremor in MS and how it impacts daily function could inform trial design for potential therapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the NARCOMS registrants who took the time to complete and return the surveys. They also thank Dr Stacey Cofield for assistance in survey design and Jeffry Hebert for database construction.

Footnotes

Contributors: JRR conceived and designed the study, performed statistical analysis, and authored and revised the manuscript. ARS participated in study design and statistical analysis, and assisted in drafting and revising the manuscript. HW, AA and WM each contributed to study design, performed blinded spiral ratings and critically revised the manuscript. GRC contributed to the design and statistical analysis of the study, and provided critical review of the manuscript. All authors provided final approval of the submitted manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by an Investigator Initiated Grant/Trial Award from Biogen Idec (US-TYS-11–10238). HW and AA receive grant support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. HW is supported by K23NS067053 and AA is supported by K23NS080912.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: University of Alabama at Birmingham Internal Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Weinshenker BG, Rice GP, Noseworthy JH et al. . The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study. 3. Multivariate analysis of predictive factors and models of outcome. Brain 1991;114:1045–56. 10.1093/brain/114.2.1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koch M, Mostert J, Heersema D et al. . Tremor in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2007;254:133–45. 10.1007/s00415-006-0296-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pittock SJ, McClelland RL, Mayr WT et al. . Prevalence of tremor in multiple sclerosis and associated disability in the Olmsted County population. Mov Disord 2004;19:1482–5. 10.1002/mds.20227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alusi SH, Worthington J, Glickman S et al. . A study of tremor in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2001;124:720–30. 10.1093/brain/124.4.720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pittock SJ, Mayr WT, McClelland RL et al. . Disability profile of MS did not change over 10 years in a population-based prevalence cohort. Neurology 2004;62:601–6. 10.1212/WNL.62.4.601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. NARCOMS Multiple Sclerosis Registry (on-line). http://www.narcoms.org/ (accessed 8 Dec 2013).

- 7.Marrie RA, Goldman M. Validation of the NARCOMS Registry: Tremor and Coordination Scale. Int J MS Care 2011;13:114–20. 10.7224/1537-2073-13.3.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bain PG, Findley LJ. Assessing tremor severity. 1st edn. London: Smith-Gordon and Company Ltd, 1993:5–24. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bain PG, Findley LJ, Atchison P et al. . Assessing tremor severity. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1993;56:868–73. 10.1136/jnnp.56.8.868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alusi SH, Worthington J, Glickman S et al. . Evaluation of three different ways of assessing tremor in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;68:756–60. 10.1136/jnnp.68.6.756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rinker JR, Salter AR, Cutter GR. Improvement of multiple sclerosis-associated tremor as a treatment effect of natalizumab. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2014;3:505–12. 10.1016/j.msard.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Learmonth YC, Motl RW, Sandroff BM et al. . Validation of patient determined disease steps (PDDS) scale scores in persons with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurology 2013;13:37 10.1186/1471-2377-13-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burdine JN, Felix MR, Abel AL et al. . The SF-12 as a population health measure: an exploratory examination of potential for application. Health Serv Res 2000;35:885–904. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marrie RA, Cutter G, Tyty T et al. . Does multiple sclerosis-associated disability differ between races? Neurology 2006;66: 1235–40. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000208505.81912.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louis ED, Ottman R, Hauser WA. How common is the most common adult movement disorder? Estimates of the prevalence of essential tremor throughout the world. Mov Disord 1998;13:5–10. 10.1002/mds.870130105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louis ED, Ferreira JJ. How common is the most common adult movement disorder? Update on the worldwide prevalence of essential tremor. Mov Disord 2010;25:534–41. 10.1002/mds.22838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marrie RA, Cutter G, Tyry T et al. . Validation of the NARCOMS registry: diagnosis. Mult Scler 2007;13:770–5. 10.1177/1352458506075031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marrie RA, Cutter G, Tyry T et al. . Validation of the NARCOMS registry: fatigue assessment. Mult Scler 2005;11:583–4. 10.1191/1352458505ms1216oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marrie RA, Cutter G, Tyry T et al. . Validation of the NARCOMS registry: pain assessment. Mult Scler 2005;11:338–42. 10.1191/1352458505ms1167oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]