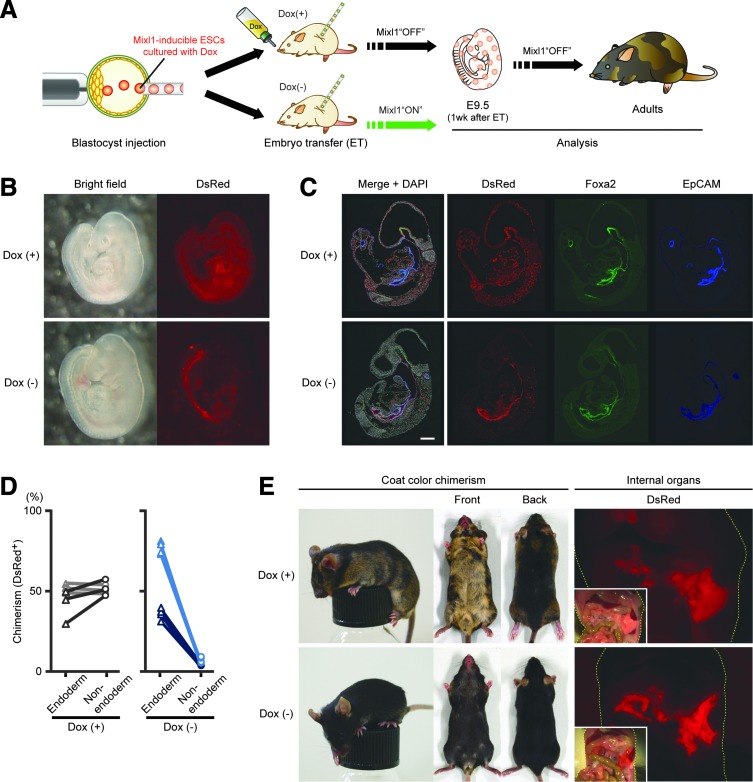

FIG. 1.

Mixl1-inducible ESCs can preferentially contribute to gut endoderm after blastocyst injection. (A) Experimental schema for analysis of chimera generated by injection of Mixl1-inducible ESCs into wild-type blastocyst. (B) Chimeric fetuses at 1 week after transfer of RT5-ESC–injected wild-type blastocysts (developmental stage: E9.5 embryo) into foster-mother uteri. Foster mothers were given drinking water with (+) or without (−) Dox. (C) Distribution of RT5-ESC–derived cells in E9.5 chimeric fetus. In Dox(−) setting, to exclude the effect of EGFP expression on multi-color staining, Dox was given to foster mothers at 1 day before analysis. Sections were immunostained for DsRed (red) and for endodermal markers Foxa2 (green) and EpCAM (blue), with nuclear counterstaining (white) using DAPI. (D) Comparison of chimerism between endodermal and nonendodermal embryonic tissues in Dox(+) and Dox(−) settings. Sections immunostained in (C) were imaged by ArrayScan technology, with collected data analyzed by FloJo software (Supplementary Fig. S2). Both Foxa2- and EpCAM-expressing cells were defined as “endoderm (triangular dots)”; cells expressing neither were defined as “nonendoderm (circular dots).” Three or four sections from each of a pair of embryos were evaluated. Values obtained from the same sections are connected by lines. (E) Adult chimeric mice generated by injection of RT5-ESCs into wild-type blastocysts. In the Dox(−) setting, foster mothers were given drinking water with Dox except during 1 week after embryo transfer. Coat-color chimerism differences between host-blastocyst progeny (BDF1xB6-derived) and donor-ESC progeny (129ola-derived) are shown, as are macroscopic views of contributions of RT5-ESC–derived cells to internal organs. Yellow dashes outline bodies. Sections in (C) were observed under confocal laser scanning microscopy. Scale bars, 100 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; ESCs, embryonic stem cells.