Abstract

Nephrotoxicity is the major dose-limiting factor for the clinical use of colistin against multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria. This study aimed to investigate the protective effect of lycopene on colistin-induced nephrotoxicity in a mouse model. Fifty mice were randomly divided into 5 groups: the control group (saline solution), the lycopene group (20 mg/kg of body weight/day administered orally), the colistin group (15 mg/kg/day administered intravenously), the colistin (15 mg/kg/day) plus lycopene (5 mg/kg/day) group, and the colistin (15 mg/kg/day) plus lycopene (20 mg/kg/day) group; all mice were treated for 7 days. At 12 h after the last dose, blood was collected for measurements of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine levels. The kidney tissue samples were obtained for examination of biomarkers of oxidative stress and apoptosis, histopathological assessment, and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis. Colistin treatment significantly increased concentrations of BUN and serum creatinine, tubular apoptosis/necrosis, lipid peroxidation, and heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) activity, while the treatment decreased the levels of endogenous antioxidant biomarkers glutathione (GSH), catalase (CAT), and superoxide dismutase (SOD). Notably, the changes in the levels of all biomarkers were attenuated in the kidneys of mice treated with colistin by lycopene (5 or 20 mg/kg). Lycopene treatment, especially in the colistin plus lycopene (20 mg/kg) group, significantly downregulated the expression of NF-κB mRNA (P < 0.01) but upregulated the expression of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and HO-1 mRNA (both P < 0.01) in the kidney compared with the results seen with the colistin group. Our data demonstrated that coadministration of 20 mg/kg/day lycopene can protect against colistin-induced nephrotoxicity in mice. This effect may be attributed to the antioxidative property of lycopene and its ability to activate the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past 2 decades, there has been a pronounced increase in the emergence of Gram-negative “superbugs” (1). This has led to serious infections that are resistant to almost all clinically available antibiotics. Such a dire situation is perpetuated by a lack of novel antibiotics in the drug developmental pipeline, leaving the world in a vulnerable state with respect to these life-threatening infections (1). The dry antibacterial drug development pipeline has led to the revival of the polymyxin class of antibiotics, colistin (i.e., polymyxin E) and polymyxin B, as a last-line defense for treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative pathogens (2, 3). However, the use of polymyxins has largely been limited by nephrotoxicity, the major dose-limiting factor occurring in up to 60% of patients (4–6). As a result, development of nephroprotective agents is very important for optimizing clinical use of polymyxins.

Polymyxin-induced nephrotoxicity potentially arises from the manner in which the antibiotics are handled by the renal system (7–9). For both colistin and polymyxin B, only a very minor proportion of the dose is renally eliminated (8, 10); the majority appears to undergo extensive reabsorption after being filtered by glomeruli (8), leading to accumulation in renal tubular cells and subsequently to apoptosis and tubular damage (6, 7, 10–12). Recent studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that polymyxin-induced apoptosis in renal tubular cells appears to be mediated by oxidative stress (11, 13). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) molecules are mainly generated by mitochondria and are among the major mediators of oxidative stress; they initiate renal cell apoptosis, which finally leads to renal dysfunction (14, 15). ROS-mediated oxidative stress plays a key role in colistin-induced nephrotoxicity (12, 16–18).

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a critical transcription factor that regulates antioxidant genes by binding to antioxidant response elements (AREs) (19–22). Nrf2 activation promotes the expression of several phase II and antioxidative enzymes such as the heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), which protects the cell against apoptosis. The cytoprotection of the HO-1 isoenzyme depends on its ability to catabolize free heme, thereby preventing it from sensitizing cells to undergo apoptosis (23). Notably, Nrf2 is particularly active in tissues (e.g., kidney tissue) that are susceptible to oxidative stress from exposure to xenobiotics (24, 25). Under nominal cellular conditions, the transcriptional activity of Nrf2 is suppressed, as it remains bound by Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) in the cytoplasm (26). However, when the cell experiences oxidative stress, Nrf2 becomes dissociated from Keap1 and translocates to the nucleus, where it induces expression of ARE-dependent target genes. The Nrf2/HO-1 pathway plays an important role in the nephrotoxicity of antibiotics and toxins, including gentamicin, cisplatin, adriamycin, and manganese (22, 26–30).

Lycopene is a carotenoid compound (Fig. 1) and acts as a highly efficient antioxidant in scavenging singlet-oxygen and free radicals (31–35). Lycopene has been shown to activate the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway and can protect against nephrotoxicity induced by gentamicin, adriamycin, and cisplatin (28, 31, 36–39). Lycopene displays antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects; in one clinical trial, the data suggested that it may play an important role in protection against various chronic diseases (e.g., cancer) (40). In the present study, we investigated the nephroprotective effect of lycopene on polymyxin-induced nephrotoxicity and the involvement of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in a mouse model.

FIG 1.

Structure of lycopene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Colistin (sulfate) was purchased from Zhejiang Shenghua Biology Co., Ltd. (Zhengjiang, China) (20,400 units/mg). Lycopene was obtained from the Pure Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Hemin, glucose-6-phosphate, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Animal experiments.

This animal study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the China Agricultural University. Adult Kunming mice (female, 6 to 8 weeks of age, 18 to 22 g) were obtained from Vital River Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The animal laboratory was maintained at approximately 22°C and 50% relative humidity with a 12-h light-dark cycle. An acclimation period of 1 week was employed prior to the experiments. Mice had free access to food and water during the experiments. Fifty mice were randomly divided into five groups (n = 10 in each group): saline solution (control group), lycopene administered at 20 mg/kg of body weight/day (lycopene group), colistin at 15 mg/kg/day (colistin group), colistin at 15 mg/kg/day plus lycopene at 5 mg/kg/day (colistin/lycopene 5 group), and colistin at 15 mg/kg/day plus lycopene at 20 mg/kg/day (colistin/lycopene 20 group). For colistin (sulfate) administration, mice were intravenously injected at 15 mg/kg/day in two doses via a 3-min infusion. In the colistin plus lycopene at 5 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg groups, mice were also orally administered 5 or 20 mg/kg/day lycopene, respectively, at 2 h before administration of intravenous colistin (15 mg/kg/day). Mice in the control group were given an equal volume of saline solution. All mice were treated for 7 days, and blood samples and kidneys were collected at 12 h after the last dose for the biochemical, histopathological, and gene expression studies described below.

Biochemical analyses.

Blood samples were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min for biochemical analysis. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels were analyzed using commercial kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Biological Engineering, Nanjing, China).

Part of kidney tissue was homogenized in 9 volumes of cold Tris buffer (0.01 M Tris-HCl, 0.1 mM EDTA-Na2, 0.01 M sucrose, 0.9% saline solution, pH 7.4) to prepare a 10% tissue homogenate and then centrifuged at 3,000 × g (4°C) for 15 min. The supernatant was collected for measuring the concentrations of malondialdehyde (MDA), nitric oxide (NO), catalase (CAT), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), glutathione (GSH), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) using commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Biological Engineering). Protein concentrations in the supernatant were measured using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Wuhan Boster Bio-engineering Limited Co., Wuhan, China).

Histopathological examination.

For the light microscopy histological examination, the right kidneys were randomly selected from 4 mice in each group and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. The formalin-fixated tissue was embedded in paraffin, divided into 4-μm sections, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E). A semiquantitative evaluation of kidney injury was conducted, and a semiquantitative score (SQS) was employed to grade the lesion severity for each kidney sample. Scores of 0, +1, +2, +3, +4, and +5 corresponded to no change, mild change, mild to moderate change, moderate change, moderate to severe change, and severe change, respectively (12).

Activities of caspase-3, caspase-9, and HO-1.

The activities of caspase-3 and caspase-9 in the kidney were determined using commercial kits (Beyotime Bioengineering Institute Beijing, China). Total HO-1 activity was measured as described previously (41). In brief, reactions were performed in a 1.2-ml reaction mixture consisting of 0.5 mg protein from tissue homogenate, 2 mmol/liter glucose-6-phosphate, 0.2 U glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 0.8 mmol/liter NADP, and 20.0 mmol/liter hemin. Incubation was allowed to proceed for 1 h at 37°C. The results were determined spectrophotometrically by measuring the optical density at 464 nm against a baseline absorbance at 530 nm. Activity was normalized to the value for the control.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) examination.

Total RNA was isolated using the TRIzol extraction method according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA). The quality of RNA was verified by evaluating the optical density (OD) at 260 nm and 280 nm. One microgram of total RNA was processed to produce cDNA by the use of reverse transcription and a PrimeScript reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). The PCR conditions and primers used were as follows: Nrf2 forward, 5′-CAC ATT CCC AAA CAA GAT GC-3′; Nrf2 reverse, 5′-TCT TTT TCC AGC GAG GAG AT-3′; HO-1 forward, 5′-CGT GCT CGA ATG AAC ACT CT-3′; HO-1 reverse, 5′-GGA AGC TGA GAG TGA GGA CC-3′; NF-κB forward, 5′-CAC TGT CTG CCT CTC TCG TCT-3′; NF-κB reverse, 5′-AAG GAT GTC TCC ACA CCA CTG-3′; glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) forward, 5′-ACA GTC CAT GCC ATC ACT GCC-3′; GAPDH reverse, 5′-GCC TGC TTC ACC ACC TTC TTG-3′. Standard cycling conditions were used, including a preamplification step of 95°C for 10 min, followed by amplification for 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 20 s. All reactions were conducted in three replicates. GAPDH was used as an internal control, and fold change in gene expression was calculated using the threshold cycle method (2−ΔΔCT).

Statistical analyses.

Results are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD). A one-way analysis of variance, followed by a Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) test, was employed to compare any two means when the variance was homogeneous; otherwise, Dunnett's T3 test was used (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A P value of <0.05 represented significant difference.

RESULTS

Effect of lycopene on the levels of BUN, serum creatinine, and oxidative stress biomarkers in the kidney.

Compared to the control level, BUN and serum creatinine levels did not change in the lycopene treatment group but significantly increased in the colistin-treated mice, indicating impaired kidney function (Table 1). The BUN and creatinine levels were normal after coadministration of lycopene at 20 mg/kg of body weight/day with colistin (Table 1). Colistin treatment also significantly increased the concentrations of MDA and NO as well as iNOS activity (all P < 0.01) in the kidney tissue, while the GSH level and activities of SOD and CAT substantially decreased (all P < 0.01; Table 2). The levels of MDA, iNOS, CAT, and GSH in the colistin/lycopene 20 mg/kg group were comparable to those in the untreated control group. These results show the attenuation of colistin-induced nephrotoxicity by coadministration of 20 mg/kg/day lycopene.

TABLE 1.

Concentrations of BUN and serum creatinine in different treatment groups

| Product | Concn (mean ± SD; n = 10) for indicated groupa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Lycopene | Colistin | Colistin/lycopene 5 | Colistin/lycopene 20 | |

| BUN (mmol/liter) | 5.82 ± 1.34 | 5.97 ± 0.87 | 12.2 ± 2.93** | 7.51 ± 1.05## | 6.45 ± 1.31## |

| Creatinine (μmol/liter) | 76.9 ± 27.4 | 72.2 ± 20.6 | 219 ± 35.5** | 157 ± 32.1# | 89.8 ± 18.8## |

*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (compared to the control group); #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01 (compared to the colistin group).

TABLE 2.

Effect of lycopene on the biomarkers of renal oxidative stress induced by colistin

| Biomarker | Concn (mean ± SD; n = 10) for indicated groupa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Lycopene | Colistin | Colistin/lycopene 5 | Colistin/lycopene 20 | |

| MDA (mmol/mg pro) | 1.48 ± 0.41 | 1.45 ± 0.34 | 1.94 ± 0.36** | 1.75 ± 0.42# | 1.53 ± 0.51## |

| NO (μmol/g pro) | 4.56 ± 0.72 | 4.34 ± 0.65 | 6.45 ± 0.54** | 6.01 ± 0.72 | 5.14 ± 0.69## |

| iNOS (U/mg pro) | 0.45 ± 0.21 | 0.44 ± 0.23 | 1.09 ± 0.21** | 0.64 ± 0.34# | 0.48 ± 0.32## |

| CAT (U/mg pro) | 96.5 ± 8.42 | 99.5 ± 13.4 | 67.5 ± 10.9** | 82.4 ± 12.5# | 90.8 ± 13.1## |

| GSH (mmol/mg pro) | 55.1 ± 6.18 | 57.7 ± 7.58 | 40.3 ± 5.13** | 49.2 ± 8.89# | 55.3 ± 7.34## |

| SOD (U/mg pro) | 68.7 ± 6.23 | 71.4 ± 6.38 | 50.6 ± 9.83** | 56.8 ± 8.93 | 64.8 ± 10.1# |

MDA, malondialdehyde; NO, nitric oxide; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; CAT, catalase; GSH, glutathione; SOD, superoxide dismutase; pro, protein. Values are presented as means ± SD (n = 10). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (compared to the control group); #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01 (compared to the colistin group).

Histopathological assessment.

The representative histopathological results are shown in Fig. 2. In the kidneys from the control group and the group administered lycopene alone, no marked pathological changes were observed (Fig. 2A and B). However, in the kidneys from the colistin group, there was severe tubular damage with focal necrosis of tubular epithelial cells and numerous casts (Fig. 2C); the corresponding SQS increased to 2.75 ± 0.50 (P < 0.01). These pathological changes were significantly attenuated in the colistin/lycopene 5 mg/kg and colistin/lycopene 20 mg/kg groups (Fig. 2D, E, and F). The corresponding SQSs decreased to 1.50 ± 0.58 (P < 0.05) and 0.75 ± 0.50 (P < 0.01), respectively.

FIG 2.

Representative histopathological results and the semiquantitative scores. (A) Control group: no marked injury. (B) Lycopene group: no marked injury. (C) Colistin (15 mg/kg/day) group: marked tubular damage with necrosis and exfoliation of epithelial cells (arrows), cast formation (arrowheads), and dilation. (D) Colistin (15 mg/kg/day) plus lycopene (5 mg/kg/day) (Colistin/lycopene 5) group: mild tubular damage with necrosis (arrows) of epithelial cells and cast formations (arrowheads). (E) Colistin (15 mg/kg/day) plus lycopene (20 mg/kg/day) (Colistin/lycopene 20) group: minor tubular damage with tubular dilatation (arrows) and cast formations (arrowheads). (F) SQS values are presented as means ± SD (n = 4). **, P < 0.01 (compared to the control group); #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01 (compared to the colistin group). Data represent the results of H&E staining. Bars, 100 μm.

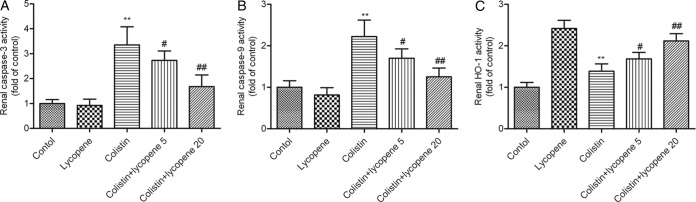

Activity of caspase-3, caspase-9, and HO-1 in the kidney.

There was a significant increase in the activities of both caspase-3 and caspase-9 in the colistin group (both P < 0.01) compared to the control group (Fig. 3A and B). The activities of both caspase-3 and caspase-9 significantly decreased in the colistin/lycopene 5 mg/kg and colistin/lycopene 20 mg/kg groups. Not surprisingly, the activity of HO-1, an antioxidative enzyme that protects cells against apoptosis, significantly increased in the colistin group compared to the control group. HO-1 activity was higher in all of the lycopene-treated groups than in the control group (Fig. 3C).

FIG 3.

Activities of caspase-3 (A), caspase-9 (B), and HO-1 (C). Values are presented as means ± SD (n = 10). **, P < 0.01 (compared to the control group); #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01 (compared to the colistin group).

Expression of OH-1, Nrf2, and NF-κB mRNA in the kidney.

Expression of Nrf2 and OH-1 mRNAs significantly increased in the colistin group and in all lycopene-treated groups compared to that in the saline solution-treated control mice (Fig. 4). In contrast, the expression of NF-κB mRNA significantly decreased in the colistin/lycopene 5 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg groups compared to the colistin group. Unlike the Nrf2 and OH-1 results, the expression of NF-κB displayed no marked changes upon lycopene treatment (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Expression of Nrf2 (A), OH-1 (B), and NF-κB (C) in the kidney. Values are presented as means ± SD (n = 10). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (compared to the control group); #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01 (compared to the colistin group).

DISCUSSION

Antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative superbugs presents a significant global medical challenge. Colistin is increasingly used as the only therapeutic option. However, recent pharmacological data indicate that plasma concentrations achieved with the currently recommended dosage regimens are suboptimal in many patients (42), potentially leading to poor clinical outcome and emergence of resistance. Simply increasing daily doses of colistin is not an option because nephrotoxicity can occur in a large proportion of patients (4, 43). In the present study, we investigated the potential nephroprotective effect of lycopene, a red-colored carotene pigment found in red fruits and vegetables, such as tomatoes, watermelons, Momordica cochinchinensis Spreng fruit, and papayas (31). Lycopene is 10-, 47-, and 100-fold more effective in quenching singlet oxygen than α-tocopherol, β-carotene, and vitamin E, respectively (32, 34). Clinical studies also demonstrated that dietary supplementation of lycopene or tomato products reduced levels of biomarkers of oxidative stress (e.g., cellular DNA damage and lipid oxidation) in healthy subjects, smokers, and type-2 diabetics (44–49). Another study showed that daily intake of 150 ml tomato juice (equal to administration of lycopene at approximately 15 mg/day) for 5 weeks can significantly reduce the serum concentration of 8-OhdG (8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine, a critical biomarker of oxidative stress) after extensive physical exercise (50). In addition, lycopene is the most effective quencher of oxygen free radicals across all of the naturally occurring carotenoids and demonstrates potential anticancer properties (35, 51); the latter has been evaluated in clinical trials in several countries (52–54).

In a mouse model, we demonstrated that coadministration of lycopene attenuated colistin-induced nephrotoxicity (Fig. 2) as shown by the decrease of BUN, serum creatinine, and caspase-dependent apoptosis levels (Table 1). These data are in line with previous studies that showed that coadministration of antioxidants can protect against colistin-induced nephrotoxicity (12, 16–18, 55). Increased production of ROS is an important mechanism in colistin-induced nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity (17, 56–58). Excessive ROS levels cause damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins, eventually leading to apoptosis (14, 59). Lycopene has been shown to interact with ROS and thereby to prevent ROS-induced tissue and cellular damage (35). Consistent with previous studies, we revealed that colistin-induced nephrotoxicity is associated with significantly increased MDA levels and a concomitant decrease in the levels of antioxidant enzymes CAT, SOD, and GSH (Table 2) (16, 18, 60, 61). In the present study, lycopene treatment restored the levels of all of these biomarkers to the normal range observed in the untreated control group (Table 2), confirming its nephroprotective effect. This protective property was also confirmed by histopathological examination of the mouse kidneys, which revealed a marked amelioration in tubular necrosis and decrease of SQSs in the lycopene-cotreated groups compared to the colistin group (Fig. 2).

Caspase-3 is a key biomarker of apoptosis (18), which can be activated by both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways and consequently lead to DNA breakdown (14, 57, 62). Several studies showed that activated caspase-3 played a key role in colistin-induced apoptosis in rat kidney tissue (12, 17, 18). The mitochondrion is a major producer of ROS and plays a central role in the process of oxidative stress (58, 63). Release of cytochrome c into the cytosol is associated with the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway which is mediated by the activation of mitochondrial permeability transition pores. The cytochrome c in the cytosol also leads to apoptosome formation, which activates caspase-9- and caspase-3-mediated apoptosis (62). Caspase 9 is an important biomarker in the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway (11, 62, 64). Our previous study demonstrated that mitochondrial dysfunction and the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway play important roles in colistin-induced nephrotoxicity (11). Previous studies identified that lycopene can protect against cell or tissue injury induced by toxins (e.g., 3-nitropropionic acid, trimethyltin, and HgCl2) via inhibiting the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway (34, 64, 65). Our findings here demonstrate that lycopene treatment markedly decreased the activities of both caspase-9 and caspase-3 (Fig. 3A and B). It is very likely that lycopene treatment minimized ROS production and the subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction (32).

The Nrf2 pathway is important in cytoprotective adaptive responses to xenobiotic insults (19). Nrf2 regulates the expression of cytoprotective genes encoding antioxidants and phase II detoxifying enzymes such as CAT, SOD, and HO-1 (22). It has been demonstrated that activation of Nrf2 is involved in drug-induced nephrotoxicity by cisplatin, gentamicin, and aristolochic acid (28, 66–70). Similarly, the mRNA levels of Nrf2 and its corresponding downstream HO-1 gene significantly increased with colistin or lycopene treatment (Fig. 4). Decreases in the GSH level in damaged cells can lead to adaptive increases in the intracellular antioxidant defense; an important event of this process is the increase of the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and its DNA binding capacity (71). The activated Nrf2 can lead to increased GSH levels through inducing the expression of the cysteine-glutamic acid exchange transporter, which protects cells from oxidative stress (71). This may explain the moderate increase of Nrf2 mRNA expression after colistin treatment. Dezoti Fonseca and colleagues showed that hemin, an inducer of HO-1, can significantly attenuate polymyxin B-induced nephrotoxicity in rats (61), which also suggested that HO-1 is involved in colistin-induced nephrotoxicity.

NF-κB plays a critical role in the regulation of many important genes involved in cellular homeostasis and cell death (26). It acts as a sensor of ROS-mediated oxidative stress (11). NF-κB activation can induce iNOS expression and then the production of NO and exacerbate oxidative stress injury (33, 51). Ozkan et al. reported that caspase-1, an activator of NF-κB, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (72), played an important role in colistin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats (18). It has been demonstrated that lycopene can suppress oxidative stress-induced NF-κB DNA binding, NF-κB/p65 nuclear translocation, and phosphorylation of IκB kinase (IKKα) and IkBα, which in turn reduces oxidative stress response (33, 73). In line with these findings, our results revealed that colistin-induced nephrotoxicity is associated with a marked increase in the level of NF-κB expression (Fig. 4), iNOS activity, and NO concentrations (Table 2). Importantly, the expression of iNOS, NO, and NF-κB in the groups treated with colistin was significantly attenuated by lycopene treatment (Table 2 and Fig. 3). This is consistent with previous findings that lycopene suppresses the production of iNOS and NO by blocking the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and translocation of NF-κB (33). In addition, cross talk between Nrf2 and NF-κB systems has been identified. Nrf2 activation caused by increased HO-1 activity can lead to the inhibition of NF-κB nuclear translocation via HO-1 end products, i.e., bilirubin and CO (71). In the present study, results indicated that the Nrf2 activation may be partially responsible for the downregulated expression of NF-κB mRNA by lycopene, which can directly scavenge singlet-oxygen and free radicals. The detailed mechanism warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, this report is the first to reveal that the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway plays a protective role in colistin-induced nephrotoxicity in mice. Importantly, our data indicate that lycopene may be able to attenuate colistin-induced nephrotoxicity via activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Award number 31372486).

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest with regard to this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Benjamin DK Jr, Bradley J, Guidos RJ, Jones RN, Murray BE, Bonomo RA, Gilbert D. 2013. 10 × ′20 Progress–development of new drugs active against gram-negative bacilli: an update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 56:1685–1694. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velkov T, Roberts KD, Nation RL, Thompson PE, Li J. 2013. Pharmacology of polymyxins: new insights into an ‘old’ class of antibiotics. Future Microbiol 8:711–724. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landman D, Georgescu C, Martin DA, Quale J. 2008. Polymyxins revisited. Clin Microbiol Rev 21:449–465. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartzell JD, Neff R, Ake J, Howard R, Olson S, Paolino K, Vishnepolsky M, Weintrob A, Wortmann G. 2009. Nephrotoxicity associated with intravenous colistin (colistimethate sodium) treatment at a tertiary care medical center. Clin Infect Dis 48:1724–1728. doi: 10.1086/599225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akajagbor DS, Wilson SL, Shere-Wolfe KD, Dakum P, Charurat ME, Gilliam BL. 2013. Higher incidence of acute kidney injury with intravenous colistimethate sodium compared with polymyxin B in critically ill patients at a tertiary care medical center. Clin Infect Dis 57:1300–1303. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kubin CJ, Ellman TM, Phadke V, Haynes LJ, Calfee DP, Yin MT. 2012. Incidence and predictors of acute kidney injury associated with intravenous polymyxin B therapy. J Infect 65:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdelraouf K, Braggs KH, Yin T, Truong LD, Hu M, Tam VH. 2012. Characterization of polymyxin B-induced nephrotoxicity: implications for dosing regimen design. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4625–4629. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00280-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Milne RW, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Smeaton TC, Coulthard K. 2003. Use of high-performance liquid chromatography to study the pharmacokinetics of colistin sulfate in rats following intravenous administration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:1766–1770. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.5.1766-1770.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandri AM, Landersdorfer CB, Jacob J, Boniatti MM, Dalarosa MG, Falci DR, Behle TF, Bordinhao RC, Wang J, Forrest A, Nation RL, Li J, Zavascki AP. 2013. Population pharmacokinetics of intravenous polymyxin B in critically ill patients: implications for selection of dosage regimens. Clin Infect Dis 57:524–531. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergen PJ, Landersdorfer CB, Zhang J, Zhao M, Lee HJ, Nation RL, Li J. 2012. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ‘old’ polymyxins: what is new? Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 74:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai C, Li J, Tang S, Li J, Xiao X. 2014. Colistin-induced nephrotoxicity in mice involves the mitochondrial, death receptor, and endoplasmic reticulum pathways. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:4075–4085. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00070-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yousef JM, Chen G, Hill PA, Nation RL, Li J. 2012. Ascorbic acid protects against the nephrotoxicity and apoptosis caused by colistin and affects its pharmacokinetics. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:452–459. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azad MA, Finnin BA, Poudyal A, Davis K, Li J, Hill PA, Nation RL, Velkov T, Li J. 24 June 2013. Polymyxin B induces apoptosis in kidney proximal tubular cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother doi: 10.1128/AAC.02587-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pabla N, Dong Z. 2008. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: mechanisms and renoprotective strategies. Kidney Int 73:994–1007. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez-Novoa JM, Quiros Y, Vicente L, Morales AI, Lopez-Hernandez FJ. 2011. New insights into the mechanism of aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity: an integrative point of view. Kidney Int 79:33–45. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghlissi Z, Hakim A, Sila A, Mnif H, Zeghal K, Rebai T, Bougatef A, Sahnoun Z. 2014. Evaluation of efficacy of natural astaxanthin and vitamin E in prevention of colistin-induced nephrotoxicity in the rat model. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 37:960–966. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yousef JM, Chen G, Hill PA, Nation RL, Li J. 2011. Melatonin attenuates colistin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4044–4049. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00328-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozkan G, Ulusoy S, Orem A, Alkanat M, Mungan S, Yulug E, Yucesan FB. 2013. How does colistin-induced nephropathy develop and can it be treated? Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3463–3469. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00343-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zoja C, Benigni A, Remuzzi G. 2014. The Nrf2 pathway in the progression of renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29(Suppl 1):i19–i24. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He M, Pan H, Chang RC, So KF, Brecha NC, Pu M. 2014. Activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant pathway contributes to the protective effects of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides in the rodent retina after ischemia-reperfusion-induced damage. PLoS One 9:e84800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan M, Ouyang Y, Jin M, Chen M, Liu P, Chao X, Chen Z, Chen X, Ramassamy C, Gao Y, Pi R. 2013. Downregulation of Nrf2/HO-1 pathway and activation of JNK/c-Jun pathway are involved in homocysteic acid-induced cytotoxicity in HT-22 cells. Toxicol Lett 223:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shelton LM, Park BK, Copple IM. 2013. Role of Nrf2 in protection against acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 84:1090–1095. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gozzelino R, Jeney V, Soares MP. 2010. Mechanisms of cell protection by heme oxygenase-1. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 50:323–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu J, Liu X, Fan J, Chen W, Wang J, Zeng Y, Feng X, Yu X, Yang X. 2014. Bardoxolone methyl (BARD) ameliorates aristolochic acid (AA)-induced acute kidney injury through Nrf2 pathway. Toxicology 318:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong YA, Lim JH, Kim MY, Kim EN, Koh ES, Shin SJ, Choi BS, Park CW, Chang YS, Chung S. 2014. Delayed treatment with oleanolic acid attenuates tubulointerstitial fibrosis in chronic cyclosporine nephropathy through Nrf2/HO-1 signaling. J Transl Med 12:50. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surh YJ, Na HK. 2008. NF-kappaB and Nrf2 as prime molecular targets for chemoprevention and cytoprotection with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant phytochemicals. Genes Nutr 2:313–317. doi: 10.1007/s12263-007-0063-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H, Wu S, Shi N, Lian S, Lin W. 2011. Nrf2/HO-1 pathway activation by manganese is associated with reactive oxygen species and ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, not MAPKs signaling. J Appl Toxicol 31:690–697. doi: 10.1002/jat.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sahin K, Tuzcu M, Sahin N, Ali S, Kucuk O. 2010. Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway may be the prime target for chemoprevention of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by lycopene. Food Chem Toxicol 48:2670–2674. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalayarasan S, Prabhu PN, Sriram N, Manikandan R, Arumugam M, Sudhandiran G. 2009. Diallyl sulfide enhances antioxidants and inhibits inflammation through the activation of Nrf2 against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in Wistar rats. Eur J Pharmacol 606:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang XJ, Li Y, Luo L, Wang H, Chi Z, Xin A, Li X, Wu J, Tang X. 2014. Oxaliplatin activates the Keap1/Nrf2 antioxidant system conferring protection against the cytotoxicity of anticancer drugs. Free Radic Biol Med 70:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erman F, Tuzcu M, Orhan C, Sahin N, Sahin K. 2014. Effect of lycopene against cisplatin-induced acute renal injury in rats: organic anion and cation transporters evaluation. Biol Trace Elem Res 158:90–95. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-9914-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yue R, Hu H, Yiu KH, Luo T, Zhou Z, Xu L, Zhang S, Li K, Yu Z. 2012. Lycopene protects against hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced apoptosis by preventing mitochondrial dysfunction in primary neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes. PLoS One 7:e50778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng D, Ling WH, Duan RD. 2010. Lycopene suppresses LPS-induced NO and IL-6 production by inhibiting the activation of ERK, p38MAPK, and NF-kappaB in macrophages. Inflamm Res 59:115–121. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-0077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ateşşahin A, Ceribaşi AO, Yilmaz S. 2007. Lycopene, a carotenoid, attenuates cyclosporine-induced renal dysfunction and oxidative stress in rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 100:371–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palozza P, Catalano A, Simone R, Cittadini A. 2012. Lycopene as a guardian of redox signalling. Acta Biochim Pol 59:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dogukan A, Tuzcu M, Agca CA, Gencoglu H, Sahin N, Onderci M, Ozercan IH, Ilhan N, Kucuk O, Sahin K. 2011. A tomato lycopene complex protects the kidney from cisplatin-induced injury via affecting oxidative stress as well as Bax, Bcl-2, and HSPs expression. Nutr Cancer 63:427–434. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.535958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yilmaz S, Atessahin A, Sahna E, Karahan I, Ozer S. 2006. Protective effect of lycopene on adriamycin-induced cardiotoxicity and nephrotoxicity. Toxicology 218:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karahan I, Atessahin A, Yilmaz S, Ceribasi AO, Sakin F. 2005. Protective effect of lycopene on gentamicin-induced oxidative stress and nephrotoxicity in rats. Toxicology 215:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Atessahin A, Yilmaz S, Karahan I, Ceribasi AO, Karaoglu A. 2005. Effects of lycopene against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and oxidative stress in rats. Toxicology 212:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ip BC, Wang XD. 2013. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma: implications for lycopene intervention. Nutrients 6:124–162. doi: 10.3390/nu6010124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taye A, Ibrahim BM. 2013. Activation of renal haeme oxygenase-1 alleviates gentamicin-induced acute nephrotoxicity in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol 65:995–1004. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garonzik SM, Li J, Thamlikitkul V, Paterson DL, Shoham S, Jacob J, Silveira FP, Forrest A, Nation RL. 2011. Population pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulfonate and formed colistin in critically ill patients from a multicenter study provide dosing suggestions for various categories of patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:3284–3294. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01733-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ko H, Jeon M, Choo E, Lee E, Kim T, Jun JB, Gil HW. 2011. Early acute kidney injury is a risk factor that predicts mortality in patients treated with colistin. Nephron Clin Pract 117:c284–c288. doi: 10.1159/000320746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Devaraj S, Mathur S, Basu A, Aung HH, Vasu VT, Meyers S, Jialal I. 2008. A dose-response study on the effects of purified lycopene supplementation on biomarkers of oxidative stress. J Am Coll Nutr 27:267–273. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steinberg FM, Chait A. 1998. Antioxidant vitamin supplementation and lipid peroxidation in smokers. Am J Clin Nutr 68:319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Upritchard JE, Sutherland WH, Mann JI. 2000. Effect of supplementation with tomato juice, vitamin E, and vitamin C on LDL oxidation and products of inflammatory activity in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 23:733–738. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.6.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hadley CW, Clinton SK, Schwartz SJ. 2003. The consumption of processed tomato products enhances plasma lycopene concentrations in association with a reduced lipoprotein sensitivity to oxidative damage. J Nutr 133:727–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Porrini M, Riso P, Brusamolino A, Berti C, Guarnieri S, Visioli F. 2005. Daily intake of a formulated tomato drink affects carotenoid plasma and lymphocyte concentrations and improves cellular antioxidant protection. Br J Nutr 93:93–99. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Visioli F, Riso P, Grande S, Galli C, Porrini M. 2003. Protective activity of tomato products on in vivo markers of lipid oxidation. Eur J Nutr 42:201–206. doi: 10.1007/s00394-003-0415-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harms-Ringdahl M, Jenssen D, Haghdoost S. 2012. Tomato juice intake suppressed serum concentration of 8-oxodG after extensive physical activity. Nutr J 11:29. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sahin K, Sahin N, Kucuk O. 2010. Lycopene and chemotherapy toxicity. Nutr Cancer 62:988–995. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2010.509838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang X, Yang Y, Wang Q. 2014. Lycopene can reduce prostate-specific antigen velocity in a phase II clinical study in Chinese population. Chin Med J (Engl) 127:2143–2146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morgia G, Cimino S, Favilla V, Russo GI, Squadrito F, Mucciardi G, Masieri L, Minutoli L, Grosso G, Castelli T. 2013. Effects of Serenoa repens, selenium and lycopene (Profluss®) on chronic inflammation associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia: results of “FLOG” (Flogosis and Profluss in Prostatic and Genital Disease), a multicentre Italian study. Int Braz J Urol 39:214–221. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2013.02.10.23683667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kucuk O, Sarkar FH, Djuric Z, Sakr W, Pollak MN, Khachik F, Banerjee M, Bertram JS, Wood DP Jr. 2002. Effects of lycopene supplementation in patients with localized prostate cancer. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 227:881–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ozyilmaz E, Ebinc FA, Derici U, Gulbahar O, Goktas G, Elmas C, Oguzulgen IK, Sindel S. 2011. Could nephrotoxicity due to colistin be ameliorated with the use of N-acetylcysteine? Intensive Care Med 37:141–146. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu Y, Dai C, Gao R, Li J. 2013. Ascorbic acid protects against colistin sulfate-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells. Toxicol Mech Methods 23:584–590. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2013.807532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dai C, Zhang D, Gao R, Zhang X, Li J. 2013. In vitro toxicity of colistin on primary chick cortex neurons and its potential mechanism. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 36:659–666. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dai C, Li J, Li J. 2013. New insight in colistin induced neurotoxicity with the mitochondrial dysfunction in mice central nervous tissues. Exp Toxicol Pathol 65:941–948. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu Y, Ruan S, Wu X, Chen H, Zheng K, Fu B. 2013. Autophagy and apoptosis in tubular cells following unilateral ureteral obstruction are associated with mitochondrial oxidative stress. Int J Mol Med 31:628–636. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keirstead ND, Wagoner MP, Bentley P, Blais M, Brown C, Cheatham L, Ciaccio P, Dragan Y, Ferguson D, Fikes J, Galvin M, Gupta A, Hale M, Johnson N, Luo W, McGrath F, Pietras M, Price S, Sathe AG, Sasaki JC, Snow D, Walsky RL, Kern G. 2014. Early prediction of polymyxin-induced nephrotoxicity with next-generation urinary kidney injury biomarkers. Toxicol Sci 137:278–291. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dezoti Fonseca C, Watanabe M, Vattimo Mde F. 2012. Role of heme oxygenase-1 in polymyxin B-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:5082–5087. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00925-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elmore S. 2007. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol 35:495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coskun PE, Busciglio J. 2012. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Down's syndrome: relevance to aging and dementia. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res 2012:383170. doi: 10.1155/2012/383170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qu M, Zhou Z, Chen C, Li M, Pei L, Chu F, Yang J, Wang Y, Li L, Liu C, Zhang L, Zhang G, Yu Z, Wang D. 2011. Lycopene protects against trimethyltin-induced neurotoxicity in primary cultured rat hippocampal neurons by inhibiting the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Neurochem Int 59:1095–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kumar P, Kalonia H, Kumar A. 2009. Lycopene modulates nitric oxide pathways against 3-nitropropionic acid-induced neurotoxicity. Life Sci 85:711–718. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kilic U, Kilic E, Tuzcu Z, Tuzcu M, Ozercan IH, Yilmaz O, Sahin F, Sahin K. 2013. Melatonin suppresses cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity via activation of Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway. Nutr Metab (Lond) 10:7. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gounder VK, Arumugam S, Arozal W, Thandavarayan RA, Pitchaimani V, Harima M, Suzuki K, Nomoto M, Watanabe K. 2014. Olmesartan protects against oxidative stress possibly through the Nrf2 signaling pathway and inhibits inflammation in daunorubicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Int Immunopharmacol 18:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moon JH, Shin JS, Kim JB, Baek NI, Cho YW, Lee YS, Kay HY, Kim SD, Lee KT. 2013. Protective effects of 6-hydroxy-1-methylindole-3-acetonitrile on cisplatin-induced oxidative nephrotoxicity via Nrf2 inactivation. Food Chem Toxicol 62:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tsai PY, Ka SM, Chang JM, Chen HC, Shui HA, Li CY, Hua KF, Chang WL, Huang JJ, Yang SS, Chen A. 2011. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate prevents lupus nephritis development in mice via enhancing the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway and inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Free Radic Biol Med 51:744–754. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee CK, Park KK, Chung AS, Chung WY. 2012. Ginsenoside Rg3 enhances the chemosensitivity of tumors to cisplatin by reducing the basal level of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2-mediated heme oxygenase-1/NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase-1 and prevents normal tissue damage by scavenging cisplatin-induced intracellular reactive oxygen species. Food Chem Toxicol 50:2565–2574. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bellezza I, Tucci A, Galli F, Grottelli S, Mierla AL, Pilolli F, Minelli A. 2012. Inhibition of NF-kappaB nuclear translocation via HO-1 activation underlies alpha-tocopheryl succinate toxicity. J Nutr Biochem 23:1583–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lamkanfi M, Kalai M, Saelens X, Declercq W, Vandenabeele P. 2004. Caspase-1 activates nuclear factor of the kappa-enhancer in B cells independently of its enzymatic activity. J Biol Chem 279:24785–24793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400985200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Simone RE, Russo M, Catalano A, Monego G, Froehlich K, Boehm V, Palozza P. 2011. Lycopene inhibits NF-kB-mediated IL-8 expression and changes redox and PPARgamma signalling in cigarette smoke-stimulated macrophages. PLoS One 6:e19652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]