Abstract

Ethnic/racial and socioeconomic status disparities in the health care and clinical outcomes of patients with chronic kidney disease are pervasive. The vast majority of care to decrease incidence of CKD risk and progression occurs in primary care settings. High quality primary care therefore represents a key strategy through which disparities in the incidence and progression of CKD may be eliminated. The Chronic Care Model provides a framework for the delivery of high quality primary care for chronic diseases, and it is frequently used to guide health care quality improvement initiatives. Evidence suggests that Chronic Care Model constructs, including provider and organizational quality improvement initiatives focused on team approaches to chronic care (e.g., case management, community health workers), are effective in modifying patients’ CKD risks among ethnic minority and low income and patients. Other Chronic Care Model constructs, including clinical information systems (e.g., disease registries), decision support interventions, and the provision of patient centered care have been shown to improve processes related to CKD care but with limited and/or mixed effects on patient outcomes. Few studies have examined the effect of these approaches on reducing disparities. Research is needed to examine the effectiveness of these strategies to eliminate CKD disparities among vulnerable populations.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, primary care, health care disparities, quality improvement, socioeconomic status

Chronic kidney disease is a significant public health problem that is characterized by marked disparities in clinical outcomes by ethnicity/race and socioeconomic status (SES), including greater CKD incidence and progression.1–5 Early recognition of patients’ CKD risks and implementation of effective therapies to slow CKD progression have been shown to improve patients’ clinical outcomes.6–9 As the first line of care for vulnerable populations, high quality primary care to identify and mitigate CKD risks represents a key strategy for eliminating disparities in CKD outcomes. However, primary care to address CKD risks among ethnic/racial minority and low income populations is suboptimal.

In this review, we discuss the important role of high quality primary care to eliminate disparities in CKD incidence and progression, factors contributing to current suboptimal primary care of vulnerable patients with CKD, and the promise of effective provider and organizational quality improvement strategies to improve the care of ethnic minority and low SES populations at risk of CKD incidence and progression.

The role of primary care in addressing CKD disparities

The vast majority of patients with CKD receive their health care from primary care providers. The Institute of Medicine defines primary care as “the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community.”10 This definition reflects the expectation that patients should ideally have many of their needs that are instrumental to CKD prevention and management addressed in primary care settings. Routine primary care visits provide opportunities for identification and management of patients’ easily identifiable risks for CKD and CKD progression (e.g., diabetes and hypertension), to address barriers to patients’ self-management of their CKD risks, and to receive timely referrals to subspecialty care.

However, disparities by ethnicity/race and SES exist in the quality of primary care for patients with CKD and CKD risk factors. Low income and ethnic/racial minority patients are less likely to receive recommended processes of care related to CKD prevention and management11, less likely to successfully modify their CKD risks by accomplishing recommended treatment goals (i.e., blood pressure control, glucose control, and cholesterol management targets)12,13, and less likely to optimally self-manage their CKD risks14. Late referrals to subspecialty care are also associated with worse clinical outcomes for African Americans compared to Whites.15

Health care disparities by ethnicity/race and SES in the primary care of CKD and its risk factors are attributed to multiple factors at patient, health care provider, and health care system levels.16 Patient factors include transportation and child care barriers that may prevent their routine access to primary care; cultural and attitudinal barriers (including health beliefs and values, preferences, and mistrust in health care providers) that may contribute to patients’ low use of primary care services; and language barriers and poor health literacy, that may contribute to patients’ poor understanding of their CKD risks and ways to modify their risks. Provider factors may include their suboptimal knowledge of CKD treatment guidelines; their biases or stereotypes regarding patients’ abilities or desires to participate in CKD care; their poor communication skills to explain to patients the importance of CKD prevention and management and engage patients in decision-making about CKD self-management; and their suboptimal interactions with patients from diverse cultural backgrounds (i.e., suboptimal cultural competence). Health system factors include office visit time constraints, limited resources for supportive care, and fragmentation of care, all of which may limit providers’ capacity to adequately follow-up and comprehensively address management of patients’ CKD risks.

Transforming Primary Care to Reduce CKD Disparities

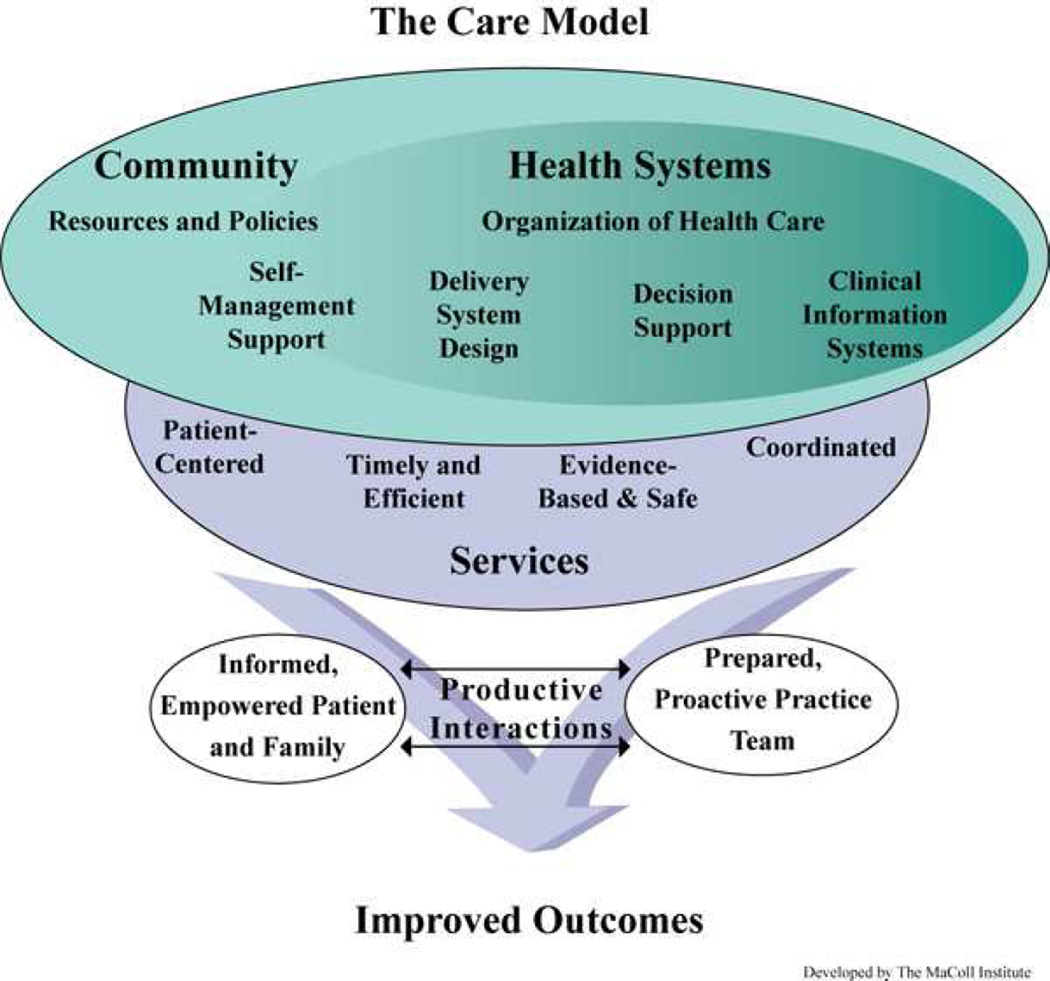

In response to increased recognition of the social determinants of health and recognition of the limitations of the current health care system to address chronic disease prevention and the health care needs of vulnerable populations, there has been renewed focus on the need for greater access and improved quality of primary care to improve population health and reduce health disparities.10 The Chronic Care Model, recognized as an effective patient-centered, population focused approach to improving the delivery of chronic disease care, has guided much of the development of quality improvement initiatives within primary care.17 The model consists of 6 core constructs including health systems, delivery system design, decision support, clinical information systems, self-management support and community resources and policies. (Figure 1) Organizational change in these interrelated areas is postulated to lead to delivery of care that is efficient, patient centered, evidence-based, and coordinated, through several mechanisms, including: (a) implementation of proactive care teams and planned interactions between health care providers and patients, (b) decision support integrated into daily practice, (c) the use of patient registries and other supportive health information technologies to guide care; and (d) the provision of patient self-management support tools and resources. The resulting productive interactions between informed, empowered patients, their families, and their prepared, proactive health care teams contribute to improved outcomes. The Chronic Care Model is closely aligned with and incorporates the core tenets of the patient-centered medical home, an additionally increasingly recognized framework for transforming primary care.18

Figure 1.

The Chronic Care Model. Developed by The MacColl Institute, © ACP-ASIM Journals and Books, reprinted with permission from ACP-ASIM Journals and Books.

Effectiveness of Provider and Organizational Strategies to Reduce CKD Disparities

While aspects of the Chronic Care Model have been applied to improving CKD-related care overall, it is unclear whether Model-based strategies promoting provider and organizational change are effective in improving outcomes among ethnic/racial minority and low SES populations and reducing inequities in the care of CKD and its risk factors. Core constructs of the Chronic Care Model implemented within the health care system (e.g., delivery system design, clinical information systems, decision support, and self-management support) could improve disparities in CKD through a variety of potential mechanisms (Table 1). We review these mechanisms and evidence regarding the effect of these constructs on reducing disparities in CKD risk or progression among ethnic/racial minority and low SES populations.

Table 1.

Provider and organizational strategies in primary care to improve health care quality among vulnerable populations

| Chronic Care Model Elements |

Description | Provider & Organizational Quality Improvement Strategies |

Mechanism for improving the quality of CKD-related care among vulnerable populations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery system design | Focus on team approaches to support chronic disease care |

|

|

| Clinical information systems | Organize individual and population data to facilitate effective and efficient care |

|

|

| Decision support | Guidance for provider decision-making |

|

|

| Self-management Support | Provider and patient partnering together to improve patient self-management |

|

|

Delivery system design

Strategies to improve the design of health care delivery systems include pro-active team-based approaches to assure regular follow-up for chronic disease management as well as the use of planned interactions to support the delivery of guideline concordant care. Strategies also include the allocation of case management services for patients at high risk for poor outcomes to support their self-management and care coordination.17 Team-based approaches to care which engage patients through outreach based on their needs rather than relying on patients’ health care seeking behaviors may reduce disparities by overcoming patient barriers (including lack of access to transportation) as well as by addressing the health system barriers (including insufficient time and poor care coordination). Strategies which are tailored to overcome additional language and literacy barriers faced by patients may have greater effectiveness among disparity populations.

Case management and community health workers are two strategies that have been increasingly incorporated into organizational quality improvement initiatives. In several systematic reviews and meta-analysis focused on patients with diabetes and hypertension, the allocation of case or disease management services to coordinate the diagnosis, treatment or ongoing management of patients’ chronic illnesses in collaboration with primary care providers has been shown to be effective in improving patient outcomes (i.e. reductions in HbA1c, blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol).19–21 Case management interventions designed to improve treatment adherence and enhance patients’ achievement of self-management of CKD risk factors have been shown to have specific benefit among ethnic/racial minority and low-income populations.22–25

Lay health workers, including community health workers and promotores de salud, (lay health advisors), can be incorporated into multidisciplinary team models to improve the health of ethnic/racial minority and low SES populations by serving as a bridge between patients’ communities and the health care system.26 These team members may help eliminate chronic care disparities through their delivery of culturally-competent education and counseling, their coordination of needed health care services, their provision of social support, and their facilitation of patients’ adoption of self-management skills to enhance treatment adherence.26 They also can help in minimizing barriers to care due to health beliefs and values. Interventions incorporating lay health workers among underserved patients with CKD risk factors have been shown to improve patients’ blood pressure control, knowledge, self-management behaviors (e.g., appointment keeping), and appropriate utilization of health services.27,28 Little work has been done to evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions among severely low-income populations (e.g., undocumented immigrants) or to evaluate these strategies’ long-term cost-effectiveness.

Clinical Information systems and decision support

Comprehensive clinical information systems provide ready access to individual and population health data to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of chronic disease care.17 Decision support is the integration of evidence-based guidelines into routine practice via effective educational methods (i.e. audit and feedback and problem-based learning) and practice aids (i.e. flow sheets or standardized clinic notes).17 With technology advances, decision support tools have increasingly been integrated within clinical information systems (i.e., computerized decision support systems). The provision of clinical information systems and decision support can enhance health care providers’ delivery of high quality care of individual patients by facilitating the provision of timely reminders to health care providers and patients regarding needed services, facilitating individual patient care planning, and facilitating information exchange between patients and between patients’ multiple health care providers to enhance the prospects for care coordination. Clinical information systems and decision support interventions may also enhance providers’ abilities to better manage their own patient populations by facilitating identification of relevant subpopulations (e.g., in disease registries) who may require more proactive or intensive care. They may also enhance providers’ and care systems’ ability to monitor their performance to support quality improvement efforts.

Patient registries may be particularly useful to improve care of CKD risks among vulnerable populations.29 Registries which facilitate the early identification of CKD, identify patients with suboptimal care quality that can be improved through interventions implemented at the point of care or implemented through outreach, and quantify and monitor CKD-related disparities may be most useful.29 Electronic alerts, reminders, or prompts to facilitate evidence-based CKD care may help to improve providers’ targeted CKD screening and management of CKD risks among high-risk vulnerable persons and may mitigate factors (i.e. providers’ bias or stereotypes) which interfere with providers’ prevention efforts or referrals to subspecialty care. Reminders can also facilitate providers’ engagement in culturally sensitive education about CKD as well as their engagement in informed and shared decision-making about renal replacement therapies.

Although systematic reviews have demonstrated the benefits of computerized decision support systems (CDSS) to improve processes of care for patients with CKD risk factors (e.g., obtaining lab tests or foot examinations), the evidence linking CDSS to patient outcomes (e.g., improved blood pressure or diabetes control) is limited.30,31 The evidence is also sparse regarding benefits related to the management of CKD. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of a CKD registry combined with periodic academic detailing in primary care practices serving 363 patients did improve achievement of one CKD process measure (ascertainment of intact parathyroid hormone), but did not appear to influence other process measures (e.g., ascertainment of hemoglobin, urine protein, phosphorous) or clinical outcomes.32 A small cluster-randomized trial evaluating an intervention integrating automated electronic medical record alerts at a university-based outpatient general internal medicine clinic (n=248 patients with CKD) also did not demonstrate any significant difference in process (i.e., proteinuria assessment) or outcome measures (i.e., blood pressure control).33 Studies regarding the effect of CDSS on reducing disparities in CKD-related care have yielded mixed findings. For instance, in a quasi-experimental study of 5101 white and 1987 black patients with diabetes receiving care within a multispecialty group practice, CDSS combined with patient reminders was effective in reducing disparities in cholesterol testing and management, but was not effective in reducing disparities in diabetes control.34 However, a second quasi-experimental study of CDSS combined with performance feedback implemented in an academic general internal practice did not show a beneficial effect in reducing racial disparities in glucose and cholesterol control among patients with diabetes.35

Clinical information systems can also be used to provide clinicians with feedback on their performance of key CKD care quality measures (e.g., obtaining yearly urine albumin quantification among patients with diabetes or appropriate use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers among patients with CKD and proteinuria). Audit and feedback to providers regarding their clinical practice performance is intended to motivate practice change when performance is not aligned with recommended clinical guidelines.36 A systematic review demonstrated the effectiveness of audit and feedback in improving processes of care and outcomes among patients with chronic illness, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes.37 While, the effectiveness of this approach in improving the care and outcomes among ethnic/racial minority and low income populations is promising, the evidence regarding its effect on reducing CKD disparities are limited. For example, in a study of providers serving a largely African American low-income population with diabetes, audit and feedback was more effective than electronic medical record reminders alone in improving patients’ intensification of diabetes treatment by providers, and in improving patients’ diabetes control.38,39 However, in a cluster-randomized controlled trial, health care providers’ performance feedback combined with cultural competence training was not effective in reducing disparities in outcomes among black and white patients with diabetes.13

Clinical information systems and decision support hold great promise in improving care quality and efficiency; however, increased attention to funneling disease management support through high-technology solutions without paying attention to the needs of vulnerable populations who may continue to have less access to these technological resources could unintentionally perpetuate or exacerbate racial disparities in care and outcomes.40 While hospitals and community health centers serving vulnerable populations had low rates of adoption of clinical information systems, more recent literature has demonstrated a significant increase in adoption rates of electronic health records in health care settings serving ethnic/racial minority and low income populations.41 To effectively reduce disparities in care and outcomes, development of health information technology resources, like all quality improvement strategies, should be tailored to specifically address barriers to quality care and self-management among vulnerable populations.

Self-management Support

Provider targeted patient self-management support interventions are designed to engage patients to be active participants in their medical care, enhance patients’ skills and confidence with chronic illness self-management, and identify and address barriers to effective self-management.17 Among vulnerable populations who experience poorer quality interactions with their provider, express greater perceived bias44, lower trust in the health care system45, and have lower health literacy46, strategies that enhance patient-centered and cultural competent interactions with providers may result in greater engagement in risk factor modification and reductions in disparities in care and outcomes.47,48

Two systematic reviews found that health care provider interventions promoting patient-centered care improve providers’ patient-centered communication skills; however, these interventions had varied effectiveness in improving patient satisfaction and other patient outcomes.49,50 The evidence regarding the effect of this approach in improving CKD-related outcomes among ethnic/racial minority and low income patients is limited. In a randomized trial, health care providers’ communication skills training combined with patient coaching in an underserved urban population with hypertension resulted in more patient-centered communication between providers and patients; however there were no observed differences in patient adherence or blood pressure control compared to the minimal intervention group (i.e., provision of educational materials to patients and providers). Among the subgroup of patients with uncontrolled hypertension, communications skills training was associated with a trend towards clinically significant reductions in systolic blood pressure.51 In a systematic review, cultural competence training of providers was consistently effective in improving health professionals’ knowledge, attitudes and skills,52,53 but the evidence for improving patient outcomes (e.g. patient satisfaction, patient trust, or disease specific outcomes such as hemoglobin A1c or blood pressure) within primary care settings was limited and did not demonstrate benefit.13,54 In a randomized controlled trial, primary care provider cultural competency training resulted in no difference in patients’ self-report of physicians’ cultural competency, patient satisfaction, or change in weight, systolic blood pressure and hemoglobin A1c.54 In a second clustered randomized controlled trial, cultural competence training combined with performance feedback for primary care providers improved providers’ acknowledgement of the presence of racial disparities in diabetes care among their own patient panel, practice, and care system, but it had no effect on reducing disparities in diabetes, blood pressure or cholesterol control between black and white patients.13

Studies of interventions to improve the cultural competency of health care for vulnerable populations have been cited as having inadequate designs to ascertain links between cultural competency training for health care providers and patients’ clinical outcomes.52,55 Further the cultural competency interventions employed in these studies are cited as featuring highly heterogeneous curricular content and educational methods, limiting the identification of clues to what particular aspects of interventions could yield the greatest benefit.52,55 The extent to which cultural competency training employed in these studies was specifically intended to influence patients’ chronic disease self-management skills is also unclear. While some approaches to cultural competency provider training may improve patients’ perceptions of and satisfaction with their care, patients’ improved perceptions and satisfaction may not, in turn, strongly influence their chronic disease self-management skills and subsequent clinical outcomes relevant to CKD care. Work is needed to standardize definitions of cultural competency. Further, those designing and applying cultural competency interventions should clearly specify the mechanisms through which interventions are hypothesized to improve clinical outcomes (e.g., through enhancing patient satisfaction or centeredness of care, through enhancing access to care, or through specifically targeting patients’ self-management behaviors). Rigorous pragmatic clinical trials studying the effect of directed cultural competency interventions on hypothesized mechanisms for improved outcomes in vulnerable populations will add evidence to further support this training to improve the primary care of vulnerable populations with CKD.

Conclusions

The vast majority of responsibility for CKD prevention and management falls to primary care providers, who currently have limited support and resources to effectively prevent CKD and its consequences among vulnerable populations. The Chronic Care Model suggests that intervening on six core constructs (i.e., health systems, delivery system design, decision support, clinical information systems, self-management support and community resources and policies) is necessary to produce informed, empowered patients and families capable of adequate chronic disease self-management and to produce primary care teams with the necessary skills, information, and resources to deliver efficient, high quality chronic disease care. Evidence suggests interventions addressing various Chronic Care Model constructs to improve aspects of care relevant to minimizing CKD risk among vulnerable populations have had modest success at best. However, studies have been limited by suboptimal designs, heterogeneous approaches, and varied populations.

To move efforts to improve outcomes of vulnerable populations at risk of CKD forward, at least two key approaches are needed. First, health systems which care for traditionally underserved populations will likely need to invest greater resources to support primary care providers in delivering CKD care (e.g., by improving multidisciplinary staff capacity, supporting enhanced care coordination, providing improved decision-support, or through addressing barriers to primary care access (e.g., through use of telemedicine). Well-documented strain on primary care systems is exacerbated by inadequate resources to support the care of patients with complex medical needs such as those at risk of CKD. Strategies incorporating multidisciplinary, integrated care management strategies, which may more specifically target barriers to optimal care among vulnerable populations, appear to have the strongest evidence base to support their implementation to improve patient outcomes in ethnic/racial minority and low-income populations and could be embraced by health care payers and policy makers. Evidence also suggests implementation of quality improvement initiatives that specifically target cultural, logistical, educational, and language barriers to optimal chronic disease care and patient self-management may improve outcomes of vulnerable populations and reduce disparities in CKD care and outcomes. Second, studies specifically examining the effectiveness of provider, organizational and multi-component quality improvement initiatives targeting health care delivery system design changes, clinical information systems, decision support, and self-management support on the elimination of racial and SES disparities in CKD are needed. Special attention to identifying the key mechanisms through which such interventions may yield improved outcomes and to developing culturally tailored strategies to modify intervention targets may yield improved health outcomes and decrease CKD risk among vulnerable populations.

Clinical Summary.

High quality primary care represents a key strategy for improving patients’ clinical outcomes overall and for eliminating ethnic/racial and socioeconomic disparities in CKD incidence and progression.

The Chronic Care Model provides a framework to promote the delivery of high quality primary care and holds promise for addressing the complex needs of ethnic/racial minorities and low socioeconomic status patients.

Although evidence is limited regarding the effectiveness of provider and organizational strategies to reduce disparities in CKD among vulnerable populations, health systems will likely need to invest further resources to improve the provision of multidisciplinary services to support vulnerable populations at risk of CKD in primary care.

Further work is needed to address specific logistical, cultural, language and educational barriers to care faced by vulnerable patient populations to improve the effectiveness of primary care and reduce CKD risks among vulnerable subgroups.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant K23DK094975 (Greer).The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Closure Statement: The authors have no financial conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Tarver-Carr ME, Powe NR, Eberhardt MS, et al. Excess risk of chronic kidney disease among African-American versus white subjects in the United States: a population-based study of potential explanatory factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2363–2370. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000026493.18542.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClellan WM, Newsome BB, McClure LA, et al. Poverty and racial disparities in kidney disease: the REGARDS study. Am J Nephrol. 2010;32:38–46. doi: 10.1159/000313883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volkova N, McClellan W, Klein M, et al. Neighborhood poverty and racial differences in ESRD incidence. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:356–364. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li S, McAlpine DD, Liu J, Collins AJ. Differences between blacks and whites in the incidence of end-stage renal disease and associated risk factors. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 2004;11:5–13. doi: 10.1053/j.arrt.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans K, Coresh J, Bash LD, et al. Race differences in access to health care and disparities in incident chronic kidney disease in the US. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:899–908. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaede P, Vedel P, Larsen N, Jensen GV, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Multifactorial intervention and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:383–393. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jafar TH, Stark PC, Schmid CH, et al. Progression of chronic kidney disease: the role of blood pressure control, proteinuria, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition: a patient-level meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:244–252. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-4-200308190-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunz R, Friedrich C, Wolbers M, Mann JF. Meta-analysis: effect of monotherapy and combination therapy with inhibitors of the renin angiotensin system on proteinuria in renal disease. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:30–48. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-1-200801010-00190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navaneethan SD, Pansini F, Perkovic V, et al. HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) for people with chronic kidney disease not requiring dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007784. CD007784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IOM. (Institute of Medicine) Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.2012 National Healthcare Disparities Report: Chapter 2. Effectiveness (continued) [Accessed March 27, 2014];Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2013 at http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhdr12/chap2a.html.

- 12.Allen AS, Forman JP, Orav EJ, Bates DW, Denker BM, Sequist TD. Primary care management of chronic kidney disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:386–392. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1523-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sequist TD, Fitzmaurice GM, Marshall R, et al. Cultural competency training and performance reports to improve diabetes care for black patients: a cluster randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:40–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine DA, Allison JJ, Cherrington A, Richman J, Scarinci IC, Houston TK. Disparities in self-monitoring of blood glucose among low-income ethnic minority populations with diabetes, United States. Ethnicity & disease. 2009;19:97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinchen KS, Sadler J, Fink N, et al. The timing of specialist evaluation in chronic kidney disease and mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:479–486. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-6-200209170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley-Matoka M, Fine MJ. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2113–2121. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arend J, Tsang-Quinn J, Levine C, Thomas D. The patient-centered medical home: history, components, and review of the evidence. The Mount Sinai journal of medicine, New York. 2012;79:433–450. doi: 10.1002/msj.21326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tricco AC, Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, et al. Effectiveness of quality improvement strategies on the management of diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:2252–2261. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60480-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welch G, Garb J, Zagarins S, Lendel I, Gabbay RA. Nurse diabetes case management interventions and blood glucose control: results of a meta-analysis. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2010;88:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glynn LG, Murphy AW, Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Interventions used to improve control of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005182.pub4. CD005182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Closing the gap: effect of diabetes case management on glycemic control among low-income ethnic minority populations: the California Medi-Cal type 2 diabetes study. Diabetes care. 2004;27:95–103. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma J, Berra K, Haskell WL, et al. Case management to reduce risk of cardiovascular disease in a county health care system. Archives of internal medicine. 2009;169:1988–1995. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glazier RH, Bajcar J, Kennie NR, Willson K. A systematic review of interventions to improve diabetes care in socially disadvantaged populations. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1675–1688. doi: 10.2337/dc05-1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hebert PL, Sisk JE, Tuzzio L, et al. Nurse-led disease management for hypertension control in a diverse urban community: a randomized trial. Journal of general internal medicine. 2012;27:630–639. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1924-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brownstein JN, Chowdhury FM, Norris SL, et al. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of people with hypertension. American journal of preventive medicine. 2007;32:435–447. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski JL, Nishikawa B, et al. Outcomes and costs of community health worker interventions: a systematic review. Med Care. 2010;48:792–808. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35b51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McBride D, Dohan D, Handley MA, Powe NR, Tuot DS. Developing a CKD Registry in Primary Care: Provider Attitudes and Input. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2013 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293:1223–1238. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cleveringa FG, Gorter KJ, van den Donk M, van Gijsel J, Rutten GE. Computerized decision support systems in primary care for type 2 diabetes patients only improve patients' outcomes when combined with feedback on performance and case management: a systematic review. Diabetes technology & therapeutics. 2013;15:180–192. doi: 10.1089/dia.2012.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drawz PE, Miller RT, Singh S, Watts B, Kern E. Impact of a chronic kidney disease registry and provider education on guideline adherence - a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2012;12:62. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdel-Kader K, Fischer GS, Li J, Moore CG, Hess R, Unruh ML. Automated clinical reminders for primary care providers in the care of CKD: a small cluster-randomized controlled trial. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2011;58:894–902. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sequist TD, Adams A, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, Ayanian JZ. Effect of quality improvement on racial disparities in diabetes care. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:675–681. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.6.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jean-Jacques M, Persell SD, Thompson JA, Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW. Changes in disparities following the implementation of a health information technology-supported quality improvement initiative. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:71–77. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1842-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larson EL, Patel SJ, Evans D, Saiman L. Feedback as a strategy to change behaviour: the devil is in the details. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2013;19:230–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01801.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3. CD000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ziemer DC, Doyle JP, Barnes CS, et al. An intervention to overcome clinical inertia and improve diabetes mellitus control in a primary care setting: Improving Primary Care of African Americans with Diabetes (IPCAAD) 8. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:507–513. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phillips LS, Ziemer DC, Doyle JP, et al. An endocrinologist-supported intervention aimed at providers improves diabetes management in a primary care site: improving primary care of African Americans with diabetes (IPCAAD) 7. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2352–2360. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopez L, Green AR, Tan-McGrory A, King R, Betancourt JR. Bridging the digital divide in health care: the role of health information technology in addressing racial and ethnic disparities. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety / Joint Commission Resources. 2011;37:437–445. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wittie M, Ngo-Metzger Q, Lebrun-Harris L, Shi L, Nair S. Enabling Quality: Electronic Health Record Adoption and Meaningful Use Readiness in Federally Funded Health Centers. Journal for healthcare quality : official publication of the National Association for Healthcare Quality. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jhq.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2084–2090. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cene CW, Roter D, Carson KA, Miller ER, 3rd, Cooper LA. The effect of patient race and blood pressure control on patient-physician communication. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1057–1064. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1051-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:101–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:358–365. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:175–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE., Jr Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989;27:S110–S127. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE, Jr, Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients' participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3:448–457. doi: 10.1007/BF02595921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003267.pub2. CD003267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheraghi-Sohi S, Bower P. Can the feedback of patient assessments, brief training, or their combination, improve the interpersonal skills of primary care physicians? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:179. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, et al. A randomized trial to improve patient-centered care and hypertension control in underserved primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1297–1304. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1794-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, et al. Cultural competence: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care. 2005;43:356–373. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156861.58905.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Renzaho AM, Romios P, Crock C, Sonderlund AL. The effectiveness of cultural competence programs in ethnic minority patient-centered health care--a systematic review of the literature. International journal for quality in health care : journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care / ISQua. 2013;25:261–269. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzt006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thom DH, Tirado MD, Woon TL, McBride MR. Development and evaluation of a cultural competency training curriculum. BMC medical education. 2006;6:38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Horvat L, Horey D, Romios P, Kis-Rigo J. Cultural competence education for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;5 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009405.pub2. CD009405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]