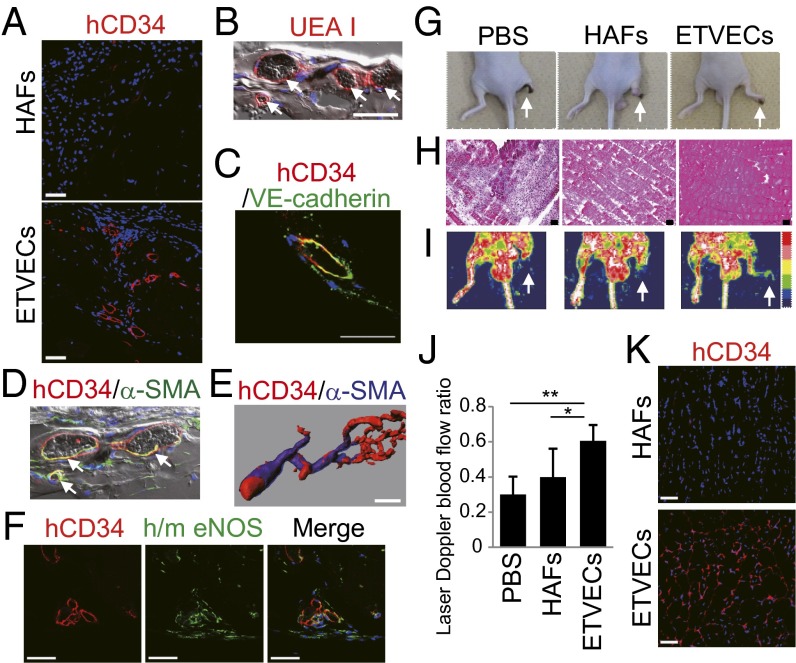

Fig. 6.

ETVECs establish mature functional vasculature in vivo. (A–F) Images of Matrigel plugs extracted from NOD SCID mice 28 (A–D and F) and 42 (E) days after the implantation of ETVECs (A–F) and HAFs (A). (B and D) The fluorescence channels were merged over bright-field pictures. White arrows indicate that erythrocytes were circulating in ETVEC-constituting vasculature. (E) Three-dimensional structure of the ETVEC-constituting vasculature. (F) Immunofluorescence images showing human CD34 (hCD34) (Left), human/mouse eNOS (h/m eNOS) (Center), and a merged image (Right) (Hoechest 33342 in blue). (G–K) Hind limb ischemia model of BALB/c-nu mice at 14 d after transplantation. (G) Representative photographs. White arrows indicate the right ischemic hind limbs. (H) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the adductor muscles of ischemic limbs. (I) Doppler images of superficial blood flow in lower limbs. Red to white color and dark-blue color on the image indicate high and low perfusion signals, respectively. White arrows indicate the right ischemic hind limbs. (J) Comparison of perfusion recovery in ischemic hind limbs. Data are mean ± SD (PBS, n = 10; HAFs, n = 10; ETVECs, n = 6). *P < 0.03; **P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA. (K) Immunofluorescence images of the cell-transplanted adductor muscles. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (Scale bars: 50 μm.)