Abstract

Erectile dysfunction (ED) has been found to frequently precedes the onset of coronary artery disease (CAD), representing an early marker of subclinical vascular disease, included CAD. Its recognition is, therefore, a “window opportunity” to prevent a coronary event by aggressive treatment of cardiovascular risk factors. The artery size hypothesis (ASH) has been proposed as a putative mechanism to explain the relationship between ED and CAD. Since atherosclerosis is a systemic disorder all major vascular beds should be affected to the same extent. However, symptoms at different points in the system rarely become evident at the same time. This is likely the result of smaller vessels (i.e. the penile artery) being able to less well tolerate the same amount of plaque when compared with larger ones (i.e. the coronary artery). If true, ED will develop before CAD. We present a case in which ED developed after a coronary event yet before a coronary recurrence potentially representing a late marker of vascular progression. Reasons for this unusual sequence are discussed as they might still fit the ASH.

Keywords: artery size hypothesis, coronary artery disease, erectile dysfunction

INTRODUCTION

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is defined as the inability to reach and maintain an erection to successfully perform sexual intercourse. The condition is present in up to 30 million men in the United States and approximately 100 million worldwide.1 In the Massachusetts Male Aging Study, 34.8% of men aged 40–60 years had moderate-to-complete ED and 15% of men aged 70 had complete ED.2 The risk of ED was directly influenced by age, number of risk factors and presence of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs).2,3 Particularly, a high prevalence of ED has been reported in conjunction with common vascular diseases, included coronary artery disease (CAD).4,5,6,7,8,9

We proposed a pathophysiological mechanism, called the “artery size” hypothesis (ASH),10,11 to explain the link between ED and CAD. Given the systemic nature of atherosclerosis, all major vascular beds should be affected to the same extent. However, symptoms at different points in the system rarely become evident at the same time. This is likely the result of larger vessels being able to better tolerate the same amount of plaque when compared with smaller ones. If true, men with early stage ED will rarely have concomitant CAD (ED as an early marker of CAD). When atherosclerosis significantly affects coronary circulation, however, the penile artery will be even more damaged, accounting for the coexistence of sexual and anginal symptoms. Thus, ED and CAD should be considered as two different aspects of the same disease, ED should come first before CAD, and CAD patients should frequently complain of ED. However, this is not always the case.

This case example refers to a patient who developed ED after the diagnosis of CAD has been made representing the classic “exception to the rule” of the ASH. We discuss the potential pathophysiologic background that may explain what we may call the “CAD-ED-CAD sequence” and how it may still fit the ASH.

CASE EXAMPLE

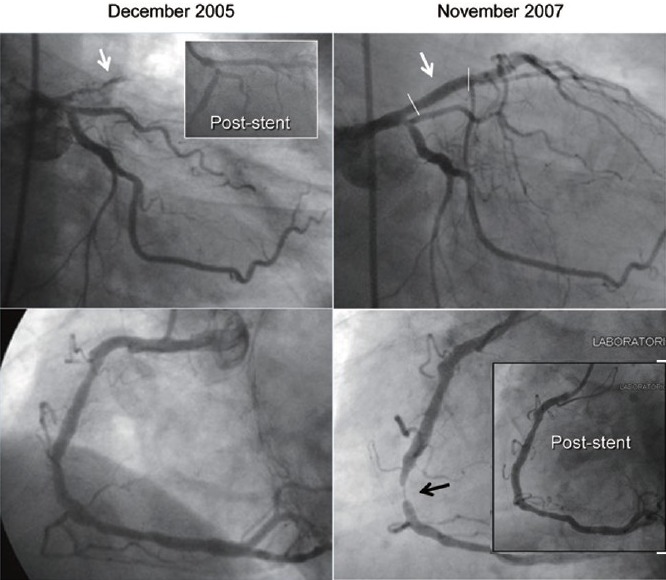

A 54-year-old man was admitted to the emergency room of our hospital because of chest pain lasting more than 12 h. His cardiovascular history was unremarkable, except for borderline hypertension and hypercholesterolemia (both untreated) and sedentary lifestyle. The electrocardiogram on admission showed anterior myocardial infarction (AMI). Coronary angiography was immediately performed, and an occluded proximal left anterior descending artery was detected (single-vessel disease). Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (two drug-eluting-stents [DESs] implanted) was performed with good vessel recanalization (Figure 1a). The post-PCI period was uneventful. A moderate left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction [EF] 45%, normal value >55%) was detected by echocardiogram. The patient was discharged on the 6th day on double antiplatelet treatment (aspirin 100 mg per day + clopidogrel 75 mg per day), beta-blocker (atenolol 50 mg per day), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ramipril 5 mg per day) and statin (atorvastatin 40 mg) (all type I, a medication according to European Society of Cardiology guidelines). A questionnaire for ED (International Index of Erectile Function 5 [IIEF-5]) was given to the patient in the 3rd post-PCI day and found to be normal (score: 23, normal value ≥23).

Figure 1.

Coronary angiography at the time of anterior myocardial infarction (left panel) and a 24 months follow-up (right panel). The left coronary artery is shown in the upper part of both panels whereas the right coronary artery in shown in the lower part. In the 2005 coronary angiography a thrombotic occlusion of the left anterior descending artery is marked by the white arrow (in the frame the angiographic result after 2 drug-eluting-stents [DES] implantations). In the 2007 coronary angiography a wide stent patency is shown, whereas a critical stenosis on the middle right coronary artery is marked by the black arrow (in the frame the angiographic result after 1 DES implantation).

Early follow-up

The patient was reassessed at a 6 months follow-up and found to be asymptomatic. He underwent a stress myocardial scintigraphy (during beta-blocker “wash-out") that turned out to be negative for inducible ischemia and a trans-thoracic echocardiogram that showed improvement (EF: 61%) of left ventricular function. Blood pressure was well under control, whereas cholesterol-low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level was still suboptimal (110 mg dl−1). At that time, he first complained of ED with an IIEF-5 score of 19. Thus, according to the favorable cardiologic results and to the potential drug-induced ED, beta-blocker was withdrawn. Atorvastatin was increased (up to 80 mg day−1) and a regimen of physical activity (at least 30 min day−1 of aerobic exercise) was prescribed. The patient was anyway commenced on sildenafil 50 mg on demand for ED treatment.

Late follow-up

At 15 months follow-up ED became moderate (IIEF-5 questionnaire score: 17) and the patient complained of chest pain associated with “unrevealing” stress test response. Cholesterol-LDL level was below 100 mg dl−1. Treatment with beta-blocker was restarted while PDE-5 inhibitor was withdrawn. A second-level noninvasive test was prescribed to better assess patient coronary reserve, but was refused. At 23 months follow-up, exercise stress test showed significant ST-segment changes involving the antero-lateral leads associated with angina pectoris. ED was now severe (IIEF-5 score: 10). Coronary angiography was performed. While a wide stents patency on the anterior descendent artery was detected, a severe (90% diameter stenosis), de-novo lesion involving the middle right coronary artery was found that was fixed with PCI and one DES (Figure 1b).

DISCUSSION

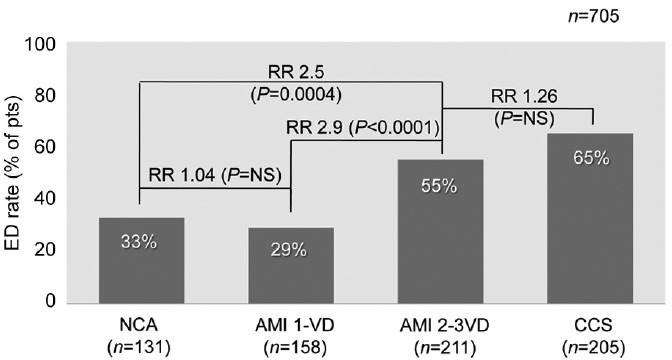

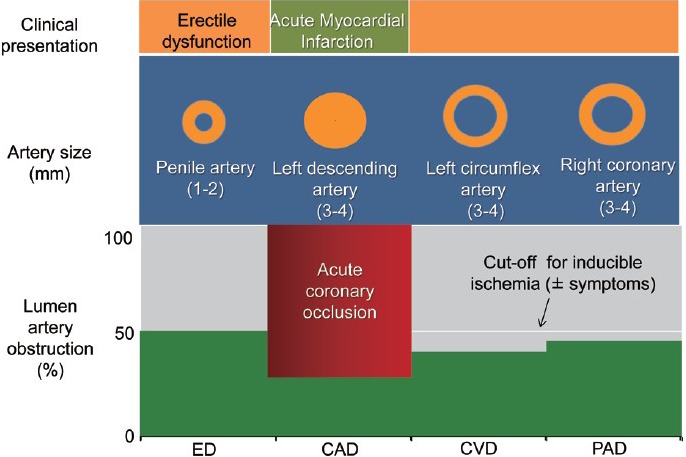

The patient cardiac history began with an AMI as the first clinical manifestation of CAD. According to the ASH, some degree of sexual dysfunction would have been expected in this “newly diagnosed” cardiac patient. However, this was not the case as shown by a normal score (≥23) of the standard self-administered IIEF questionnaire. This apparent contradiction may be explained by the different pathophysiologic background subtending acute versus chronic coronary syndromes (CCS). Acute myocardial infarction is the typical acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and is the first clinical manifestation of CAD in 80% of the cases. The remaining 20% of patients develope AMI in the setting of chronic CAD. The mechanism subtending AMI is an abrupt thrombotic coronary occlusion superimposed on a preexisting, noncritical (<50% diameter narrowing) stenosis in an otherwise angiographically normal coronary tree (single-vessel disease or mild coronary atherosclerosis pattern). The lack of preexisting significant coronary stenosis accounts for the absence of coronary symptoms until the acute event occurs. Since atherosclerosis is a systemic disorder, one can speculate that a similarly mild vascular involvement is present also at the level of hypogastric/pudendal circulation. If true, the rate of ED should be low in patients with AMI and single-vessel disease (Figure 2). In contrast to AMI, patients with CCS usually showed a severe, diffuse coronary artery involvement with long-standing anginal symptoms. Once again it can be speculated that a similarly severe vascular involvement is present also at the level of hypogastric/pudendal circulation accounting for a high rate of ED in this type of CAD. In the AssoCiatiOn Between eRectile dysfunction and coronary Artery disease (COBRA) trial12 we tested this hypothesis in 385 consecutive patients with a first diagnosis of CAD with different clinical presentation (ACS vs CCS) and the extent of vessel involvement (1 vs 2–3 vessel disease) by coronary angiography. Patients were divided into four groups: ACS with 1-vessel disease (group 1), ACS with 2–3 vessel disease (group 2), CCS (regardless the number of vessel involved, group 3) and subjects with suspected CAD but ultimately found to have entirely normal coronary anatomy (NCA group). The overall ED prevalence was 47%. When separately considered, ED rate was 22%, 55% and 65% in groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively (P = 0.0001 groups 1 vs 2 and 3 and P = NS groups 2 vs 3). The NCA group had an ED rate of 24% (P = NS vs group 1 and P < 0.0001 vs groups 2 and 3). ED difference was paralleled by difference in atherosclerotic burden (assessed by the Gensini's score) with group 1 having significantly less extent of CAD as compared to groups 2 and 3. In logistic regression analysis, age, multi-vessel versus single-vessel disease and CCS versus ACS was independent predictors of ED. Thus, the results of the COBRA trial confirmed the working hypothesis by showing a low ED rate in ACS with 1 vessel disease (similar to ED rate in normal subjects) and a high ED rate in CCS with multi-vessel disease. The group of patients with ACS and multi-vessel disease deserves some additional comments. Although this group clinical presentation was similar to group 1-that is, AMI - the coexisting diffuse coronary artery involvement detected by angiography likely accounted for an ED rate (55% vs 22%, P < 0.0001) and Gensini's score significantly higher than group 1 and similar to group 3. Thus, as far as ED rate is concerned, the “favorable pathophysiologic” background of group 1 patients was offset by the advanced (silent) atherosclerosis involvement. We confirmed the initial COBRA trial results in a widen patient population of 705 consecutive patients with CAD (Figure 3). No difference in ED rate was found between patients with NCA and group 1. Group 2 patients had a RR of ED of 2.6 (confidence interval [CI]: 1.53–4.35, P = 0.0004) versus normals and 2.9 (CI: 1.82–4.8, P < 0.0001) versus group 1, after adjustment for age, body mass index, number of risk factors and diabetes. These numbers confirm the role of the type of clinical presentation as a major determinant of the overall ED rate in CAD patients. Thus, the wide range of ED rate in previous studies (45%–75%) is the result of many factors, including patient population heterogeneity, differences in ED and CAD diagnosis and inclusion/exclusion criteria and absence of data of clinical presentation and CAD extension.

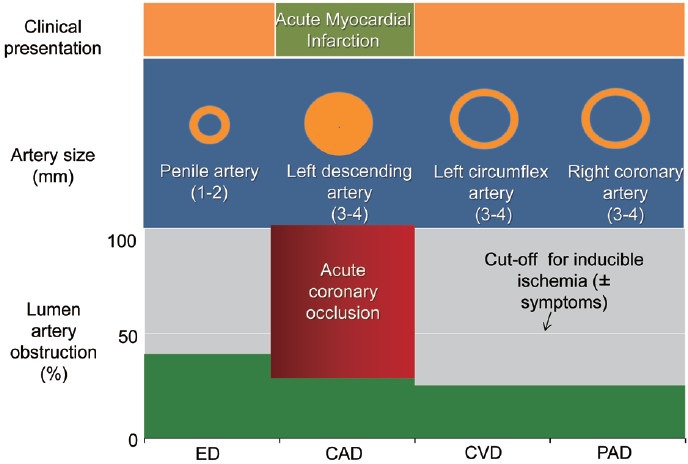

Figure 2.

A graphic depiction of the artery size hypothesis in a patient with acute myocardial infarction. In most of patients, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is due to abrupt coronary occlusion superimposing on isolated, nonsignificant coronary lesion. In other terms, AMI occurs in a modestly involved coronary tree. Penile circulation might be supposed to be similarly mild involved, accounting for low erectile dysfunction prevalence. CAD: coronary artery disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease; ED: erectile dysfunction.

Figure 3.

Erectile dysfunction (ED) prevalence in 705 consecutive patients with anterior myocardial infarction and 1 or 2–3VD, chronic coronary syndromes and normal coronary anatomy. AMI: anterior myocardial infarction; CCS: chronic coronary syndromes; RR: relative risk; NCA: normal coronary anatomy; NS: not significant; VD: vessel disease.

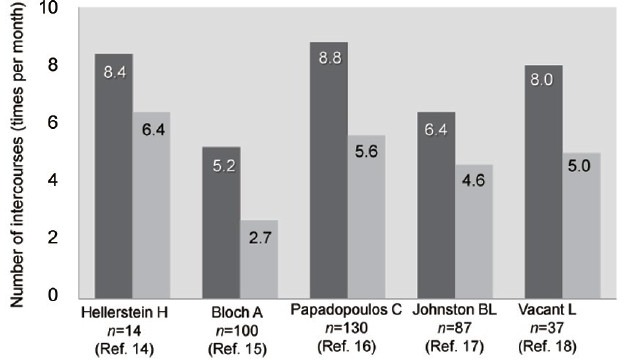

The early follow-up of this patient was characterized by the onset of ED at 6 months (ED after CAD). Potential reasons include psychological factors, drug-induced ED and progression of vascular atherosclerosis. A significant number of patients have been reported to develop sexual dysfunction within 3–6 months following a diagnosis of CVD (angina, AMI, congestive heart failure [CHF], arrhythmias) or cardiac procedures (coronary artery bypass graft, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator, cardiac transplant).13 While 25% returned to the previous level of sexual activity, 50% had reduced the number of intercourse/month, and 25% do not resume sexual activity at all. Pooling data from five previous studies,14,15,16,17,18 a common issue in subjects who were sexually active before the cardiac event was a reduction of both frequency and satisfaction with sexual activity (Figure 4). Although development of true ED has been reported in up to 40% of cases, the heterogeneity of patient population characteristics and definition/diagnosis of sexual dysfunction/ED, the lack of systematic data on precardiac event sexual status and and/or postcardiac event condition/medications significantly hamper the interpretation of these results. Psychological factors play an important role in this trend. Among those who showed reduction/cessation of sexual activity, the reasons more frequently reported were fear of coital death or repeated AMI (involving both patient and partner), performance anxiety, loss of libido (changes in sexual desire) and depression or guilty feelings.13,19 This behavior was mainly the result of lack of knowledge of the disease, need of cardiac rehabilitation and counseling and ignorance of the cardiac risk of sexual activity. In a recent multisite observational study of sexual-related outcomes after AMI in 1879 patients (the TRIUMPH registry) the absence of counseling at hospital discharge about when to resume sexual activity was a significant predictor of loss of activity at 1 year follow-up for both sexes.20

Figure 4.

Number of intercourses (times per month) in five previous studies. For each study the left column represent the precardiac event number of intercourses and the right column the postcardiac event number of intercourses.

Drugs used for treatment of CVDs have often been accused of influencing erectile function. While evidence at best is firm only for thiazide diuretics, the use of beta-blockers has been found to have neutral or detrimental effects on sexual function.21 A decreased perfusion pressure due to unopposed a-receptor stimulation (not experimentally proven or clinically investigated) and an attenuated release of sex hormones and depression of Leydig cell activity secondary to sympathetic nervous system suppression have been suggested to be involved in the reduction of sexual function.22,23 The provocative paper by Silvestri et al.24 tested the effect on sexual function of a 3 months course of atenolol 50 mg per day in three groups of patients who were blinded, knew the drug but not side-effects and knew both drug and side-effects, respectively. Interestingly, ED rate was significantly higher in those who knew the drug side-effects when compared to those without knowledge (31% vs 3%, P < 0.01). Moreover, patients with new ED entered a second phase of the study being treated with either placebo or sildenafil. ED improved in all but one case regardless the treatment confirming the role of knowing drug side-effects. If treatment with beta-blockers is clinically necessary for a CAD patient, nebivolol should be preferred. This third-generation beta-blocker has been found to own nitric-oxide-mediated vasodilator properties that answer for a neutral or even an improvement in sexual function.25,26,27,28 In general, unless ED developed within 4 weeks of initiating therapy with any cardiovascular drugs, there is little evidence to support switching the suspect drug to alleviate symptoms of sexual dysfunction.

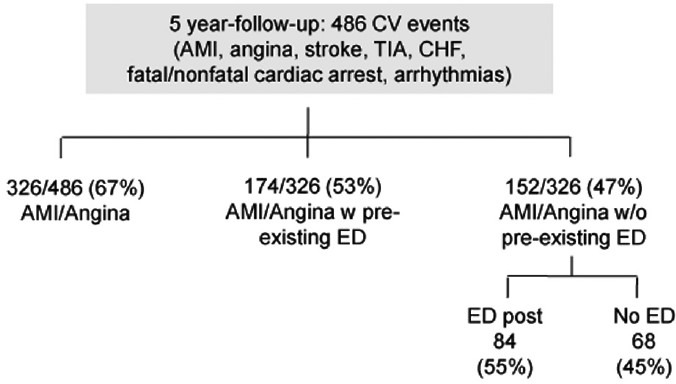

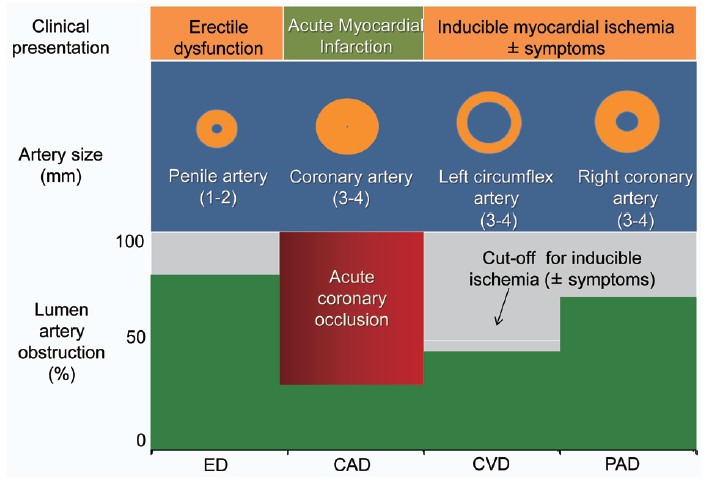

Finally, progression of cavernous (and coronary) atherosclerosis may be an alternative cause of ED after a coronary event especially if it lasts and/or worsens over time despite appropriate treatment of both psychologic and pharmacologic influences. In this occurrence, ED might represent a late warning sign of a flow-limiting coronary stenosis. The actual prevalence of ED after CAD is largely unknown. Available information came from the Thompson's study.29 The authors examined the association between ED and subsequent CVD in 9457 men enrolled in the placebo-arm of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. Among 4247 men without ED at study entry, incident ED (defined as the first report of ED of any grade) developed in 57% after 5 years of follow-up and was associated with a significant higher rate of AMI/angina when compared to men without ED. Overall, among 486 cardiovascular events (i.e. AMI, angina, transient ischemic attack, CHF, fatal/nonfatal cardiac arrest, arrhythmias), 67% involved the coronary circulation (angina and/or AMI) and occurred in roughly half of the cases after ED diagnosis (ED prior to CAD). In patients with normal sexual function who had a cardiac event, ED either followed or never occurred in 55% and 45% of cases, respectively (Figure 5). Unfortunately, in those who actually develop ED after CAD, the lack of data about psychological, pharmacological and other potential influences hampers the interpretation of the reasons for the reverse temporal sequence. We do think that ASH may still explain this occurrence. In-fact, a progression of atherosclerosis will likely affect first the smaller artery (penile circulation) leading to new ED onset despite negative cardiological tests of inducible ischemia (Figure 6). Later in the follow-up, any further plaque growing will significantly reduce coronary lumen diameter accounting for both angina symptoms and ECG changes of ischemia during the stress tests. At this time, coronary angiography may show new lesions (Figure 7). If this holds true, ED developing late after a cardiac event may represent an “early sign” of vascular disease progression in patients with known CAD with a similar pathophysiologic mechanism as in the case of ED prior to CAD. We do not have data about the average time interval between ED and “new angina” (18 months in this specific patient). As for ED prior to CAD, the length of this time interval is the result of a balance between adverse (i.e. age, risk factor profile, duration of ED at the time of the first diagnosis) and protective factors (i.e. regular exercise program, appropriate diet and pharmacological treatment of risk factors). Whatever the length of this interval is, new onset ED should rise the suspicion of CAD progression, providing a window of opportunity for an aggressive risk reduction management in these patients.

Figure 5.

Number of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events along the 5 years follow-up in the Thompson's study. AMI: anterior myocardial infarction; CHF: congestive heart failure; CV: cardiovascular; ED: erectile dysfunction; TIA: transient ischemic attack.

Figure 6.

A graphic depiction of the artery size hypothesis in a patient (as in Figure 2) with acute myocardial infarction at a 6 months follow-up time interval when erectile dysfunction developed. Progression of atherosclerosis led to a significant stenosis at the level of penile circulation. The same plaque burden was accommodated in larger arteries (right and left circumflex coronary arteries) without inducing flow-limiting stenosis. CAD: coronary artery disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease; ED: erectile dysfunction.

Figure 7.

A graphic depiction of the artery size hypothesis in a patient (as in Figure 2) with acute myocardial infarction at a 23 months follow-up time interval when angina pectoris associated with positive ST changes during exercise developed. Progression of atherosclerosis now significantly involved both penile and right coronary arteries. CAD: coronary artery disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease; ED: erectile dysfunction.

Although initial clinical data appear to support the “ASH,” exceptions may be found in the every-day clinical practice. This is due to the fact that this hypothesis besides on the conceptual model that exposure to common risk factors leads sequentially and uniformly across all vascular beds to endothelial dysfunction followed by intima-media thickening and lately, by vascular obstruction and flow-limiting stenoses. The well-known notion that upper limbs arteries are less affected by atherosclerosis as compared to lower limbs arteries suggests that the development of vascular disease is the result of a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, biochemical and mechanical factors. Thus, atherosclerosis might become clinically evident in some individual, but not in others despite a similar risk factor profile and in a given subject, vascular obstruction may involve a larger artery while sparing a smaller one.30,31 Finally, unfavorable endothelial and inflammatory state has been found to play an additional role on top of angiographic coronary involvement in the determination of ED in patients with different types of CAD.32,33 Thus, the “ASH” should be considered a putative mechanism to explain the relationship between ED and CAD.

CONCLUSIONS

This case report study depicts the less know clinical scenario of ED developing after a cardiac event. We think that this case may still fit the pathophysiological mechanism of the ASH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lue TF. Erectile dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1802–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006153422407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, Mckinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;1 51:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bortolotti A, Parazzini F, Colli E, Landoni M. The epidemiology of erectile dysfunction and its risk factors. Int J Androl. 1997;20:323–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.1998.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montorsi F, Briganti A, Salonia A, Rigatti P, Margonato A, et al. Erectile dysfunction prevalence, time of onset and association with risk factors in 300 consecutive patients with acute chest pain and angiographically documented coronary artery disease. Eur Urol. 2003;44:360–4. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solomon H, Man JW, Wierzbicki AS, Jackson G. Relation of erectile dysfunction to angiographic coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:230–1. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kloner RA, Mullin SH, Shook T, Matthews R, Mayeda G, et al. Erectile dysfunction in the cardiac patient: how common and should we treat? J Urol. 2003;170:S46–50. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000075055.34506.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burchardt M, Burchardt T, Anastasiadis AG, Kiss AJ, Shabsigh A, et al. Erectile dysfunction is a marker for cardiovascular complications and psychological functioning in men with hypertension. Int J Impot Res. 2001;13:276–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korpelainen JT, Kauhanen ML, Kemola H, Malinen U, Myllylä VV. Sexual dysfunction in stroke patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 1998;98:400–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1998.tb07321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virag R, Bouilly P, Frydman D. Is impotence an arterial disorder? A study of arterial risk factors in 440 impotent men. Lancet. 1985;1:181–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montorsi P, Montorsi F, Schulman CC. Is erectile dysfunction the “tip of the iceberg” of a systemic vascular disorder? Eur Urol. 2003;44:352–4. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montorsi P, Ravagnani PM, Galli S, Rotatori F, Briganti A, et al. The artery size hypothesis: a macrovascular link between erectile dysfunction and coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:19M–23M. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montorsi P, Ravagnani PM, Galli S, Rotatori F, Veglia F, et al. Association between erectile dysfunction and coronary artery disease. Role of coronary clinical presentation and extent of coronary vessels involvement: the COBRA trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2632–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorson AI. Sexual activity and the cardiac patient. Am J Geriatr Cardiol. 2003;12:38–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1076-7460.2003.01755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hellerstein HK, Friedman EH. Sexual activity and the postcoronary patient. Arch Intern Med. 1970;125:987–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloch A, Maeder JP, Haissly JC. Sexual problems after myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1975;90:536–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papadopoulos C, Beaumont C, Shelley SI, Larrimore P. Myocardial infarction and sexual activity of the female patient. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1528–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston BL, Cantwell JD, Watt EW, Fletcher GF. Sexual activity in exercising patients after myocardial infarction and revascularization. Heart Lung. 1978;7:1026–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vacanti L, Caramelli B. Distress: associated variables of erectile dysfunction post-acute myocardial infarction. A pilot study. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:204–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindau ST, Abramsohn E, Gosch K, Wroblewski K, Spatz ES, et al. Patterns and loss of sexual activity in the year following hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction (a United States National Multisite Observational Study) Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:1439–44. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.01.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kriston L, Günzler C, Agyemang A, Bengel J, Berner MM, et al. Effect of sexual function on health-related quality of life mediated by depressive symptoms in cardiac rehabilitation. findings of the SPARK project in 493 patients. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2044–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baumhäkel M, Schlimmer N, Kratz M, Hackett G, Jackson G, et al. Cardiovascular risk, drugs and erectile function – a systematic analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65:289–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiri R, Koskimäki J, Häkkinen J, Auvinen A, Tammela TL, et al. Cardiovascular drug use and the incidence of erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2007;19:208–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosen RC, Kostis JB, Jekelis AW. Beta-blocker effects on sexual function in normal males. Arch Sex Behav. 1988;17:241–55. doi: 10.1007/BF01541742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silvestri A, Galetta P, Cerquetani E, Marazzi G, Patrizi R, et al. Report of erectile dysfunction after therapy with beta-blockers is related to patient knowledge of side effects and is reversed by placebo. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1928–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van de Water A, Janssens W, Van Neuten J, Xhonneux R, De Cree J, et al. Pharmacological and hemodynamic profile of nebivolol, a chemically novel, potent, and selective beta 1-adrenergic antagonist. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1988;11:552–63. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198805000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritter JM. Nebivolol: endothelium-mediated vasodilating effect. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2001;38(Suppl 3):S13–6. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200112003-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doumas M, Tsakiris A, Douma S, Grigorakis A, Papadopoulos A, et al. Beneficial effects of switching from beta-blockers to nebivolol on the erectile function of hypertensive patients. Asian J Androl. 2006;8:177–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2006.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tzemos N, Lim PO, MacDonald TM. Nebivolol reverses endothelial dysfunction in essential hypertension: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. Circulation. 2001;104:511–4. doi: 10.1161/hc3001.094207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, Probstfield JL, Moinpour CM, et al. Erectile dysfunction and subsequent cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2005;294:2996–3002. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.23.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang ST, Chu CM, Hsiao JF, Chung CM, Shee JJ, et al. Coronary phenotypes in patients with erectile dysfunction and silent ischemic heart disease: a pilot study. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2798–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ponholzer A, Stopfer J, Bayer G, Susani M, Steinbacher F, et al. Is penile atherosclerosis the link between erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular risk? An autopsy study. Int J Impot Res. 2012;24:137–40. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2012.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Ioakeimidis N, Rokkas K, Vasiliadou C, et al. Unfavourable endothelial and inflammatory state in erectile dysfunction patients with or without coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2640–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vlachopoulos C, Jackson G, Stefanadis C, Montorsi P. Erectile dysfunction in the cardiovascular patient. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2034–46. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]