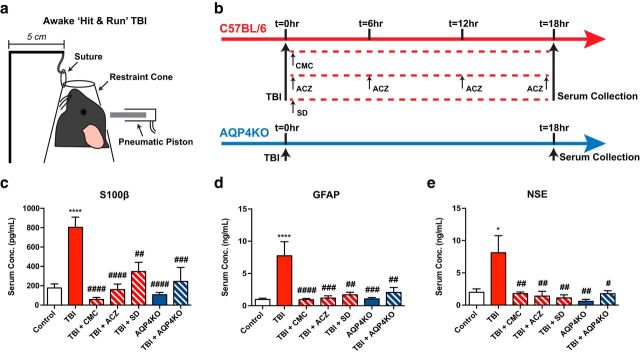

Figure 2.

Suppression of glymphatic clearance prohibits the delivery of TBI biomarkers to the serum. a, Schematic representation of nonanesthetized, closed-head “hit and run” TBI model. b, Experimental timeline: “hit and run” TBI is induced in C57BL/6 and aquaporin-4 knock-out (AQP4KO) mice. Subgroups of C57BL/6 mice then receive cisterna magna cisternotomy (CMC), acetazolamide (ACZ, 20 mg/kg, i.p.) treatment, or sleep deprivation (SD) immediately following TBI. Serum is collected 18 h subsequent to TBI and submitted for ELISA analysis of S100β, GFAP, and NSE levels. c–e, ELISA analysis of serum levels of S100β (c), GFAP (d), and NSE (e) reveals no demonstrable differences at baseline between C57BL/6 and aquaporin-4 knock-out mice. There is a significant elevation in all three of these biomarkers of brain injury 18 h following TBI. When TBI was given in conjunction with aquaporin-4 knock-out, cisterna magna cisternotomy, acetazolamide treatment, or sleep deprivation, the concentrations of all three markers in blood were significantly reduced relative to TBI alone and were not significantly different from levels seen in injury naive mice. All graphs represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 versus control (one-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc analysis). ****p < 0.0001 versus control (one-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc analysis). #p < 0.05 versus TBI (one-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc analysis). ##p < 0.01 versus TBI (one-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc analysis). ###p < 0.001 versus TBI (one-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc analysis). ####p < 0.0001 versus TBI (one-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc analysis). n = 4–10 mice per group.