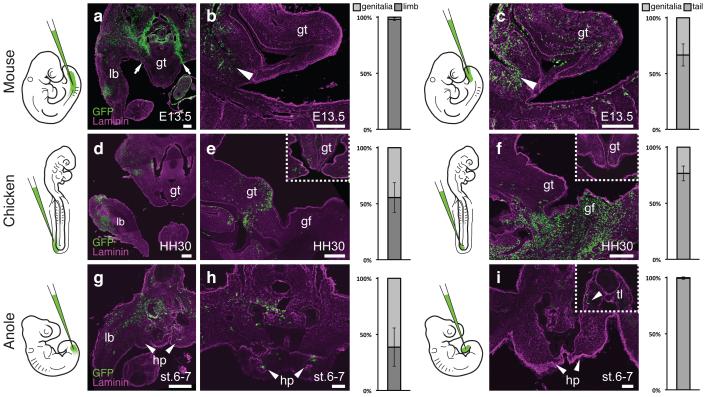

Figure 2.

Differential developmental origins of external genitalia in amniotes. (a-i) Transversal and sagittal views of GFP lentivirus injected embryos. Relative contribution of GFP-positive cells to respective organs is quantified on the right, normalized on tissue area. Error bars represent standard deviation in at least n=4 biological replicates. (a,b) Injection into the coelom at mouse E9.5 (n=48) labels the limb at E13.5, but excludes the genital tubercle (arrows). Only cells lining the peritoneal cavity are labeled (b, arrowhead), but none in the genital tubercle proper. c) Injection into the tailbud (n=101) labels cells in the genital tubercle. Accidental piercing of the coelom labels cells of the peritoneal cavity (arrowhead). (d,e) Coelom injection in HH14 chicken embryos (n=81) labels the limb and the genital tubercle at HH30. e) Sagittal and transversal close-up (inset) views. f) Sagittal and transversal close-up (inset) views of tailbud injected chick embryos (n=77), showing labeling in the genital tubercle. (g,h) Anole embryos injected into the coelom at stage 2-3 (n=94) show GFP labeling of both limb and hemipenis at stage 6-7. i) No hemipenis cells are labeled following tailbud injection (n=57), even though there are GFP-positive cells in the tail (inset, arrowhead). Scale bars, 200 μm, 50 μm (h,i). lb: limb; gt: genital tubercle; gf: genital fold; hp: hemipenis; tl: tail.