A drastic, progressive gangrenous cellulitis of the soft tissues of the deep neck and mouth floor was described in 1836 by the German surgeon Karl Friedrich Wilhelm von Ludwig [1]. Current medical care practices have meant that Ludwig's angina is rarely seen. However, once the disease process is underway, there is a serious risk of sudden death due to airway obstruction.

We describe the successful management of a case of Ludwig's angina and provide details of awake fiberoptic bronchoscope (FOB) intubation using the Air-Q®sp as a conduit.

A 57-year-old, 80 kg man presented complaining of a 3 day history of mouth and neck pain, dyspnea, and dysphagia. The patient had no recent history of dental treatment, but had a medical history of gout, hypertension for 10 years, and a mild cerebral stroke 8 years previously. Laboratory tests revealed acute kidney injury combined with severe dehydration. Despite the hospitalized treatment for 2 days, his symptoms worsened and he began to exhibit the features of Ludwig's angina. Neck computed tomography (CT) showed severe swelling of the left peritonsilar region with parapharyngeal space-occupying lesions, the aryepiglottic folds with obstruction of the left pyriform sinus were suggestive of a deep neck infection.

The patient was scheduled to undergo emergency intubation ahead of surgery. The patient underwent hemodialysis to correct his renal and hemodynamic conditions prior to the procedure. He was febrile (a tympanic temperature of 39℃), a heart rate of 115 bpm, a respiratory rate of 25, and blood pressure of 150/90 mmHg. The extent of mouth opening was slightly restricted with an inter-incisor gap of 2.5 cm. Tracheostomy was considered, but it was rejected because of concerns over the reduction in the patient's cricothyroid space caused by the swelling, the limited extension and shortness of the neck with vague landmarks. Awake FOB intubation was selected as the safest option. The necessity of the procedure was explained to the patient and written informed consent was obtained. Because of the patient's status, no premedication was administered. It was difficult to effectively administer nebulized drugs, so topical 4% lidocaine drops and a 10% lignocaine spray puff was used. The FOB (outer diameter of 3.5 mm) was fitted with a size 7.0 endotracheal tube (ET). After preoxygenation (SpO2 was 98%) and meticulous suction of oral secretions, the FOB tip was gently introduced into the oral cavity with the full cooperation. The vocal cords were visible, but it was hard to move past them because of their swollen and distorted anatomy, and moving the tongue disturbed the progress, thereby stopping the FOB tip. For the second attempt, a lubricated Air-Q®sp size 3.5 (Cookgas LLC, St. Louis, USA) was gently inserted without hindrance, and a bite block was inserted through the tube of the Air-Q®sp after removing the red-color coded connector. The prepared FOB and ET were inserted using the Air-Q®sp as a conduit; the FOB tip was able to easily pass over the vocal cords and into the trachea. There were no difficulties in removing the Air-Q®sp after intubation. Successful tracheal intubation had been achieved while maintaining spontaneous ventilation. The patient was admitted to the ICU for intensive medical care. The following morning, the patient was stable but neck CT showed the deep neck regions were aggravated. Elective surgery to incise and drain the lesions was performed. Surgery and postextubation recovery was uneventful. Clinical recovery was slow, with a persistent fever that lasted until the fifth day of hospitalization. After subsequent improvement, the patient was discharged after a total of 12 days of hospitalization.

Patients with Ludwig's angina need special attention from an intubation management perspective. Patients frequently exhibit loss of normal airway anatomy, direct visualization of the vocal cord can be impossible. It may be necessary to perform a tracheotomy if the intubation procedure fails or when faced with a "can't intubate, can't ventilate" state [2]. Transnasal FOB intubation is a more time-consuming and invasive airway procedure than orotracheal FOB intubation [3]. Orotracheal FOB intubation can take time as a result of unintended movement of oral structures and triggering of the gag reflex. Repeated attempts to intubate can increase the risk of hemorrhage and damage to the vocal cords. The more attempts that are made to intubate the patient, the worse the success rate becomes.

In our patient, neck CT performed after the intubation showed aggravations. It is important not only to recognize Ludwig's angina in the early stages, but also not to miss an opportunity to intubate at an appropriate moment. There have been reports of FOB intubation performed with the aid of supraglottic airways. However, this requires the use of a smaller-sized ET and may require the use of a tube exchanger, increasing the risk of injury and raising airway flow resistance; these can also increase the risk of complications. The i-gel™ was considered unsatisfactory on the basis of its hardness and fixed curvature. The laryngeal mask airway was also available, but was not considered suitable due to its bulky head.

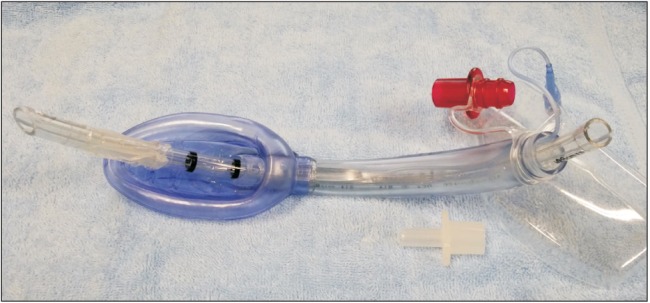

The Air-Q®sp has a number of advantages over other supraglottic airways, including a unique curvature that approximates the upper oropharyngeal airway, a shorter anterior-posterior diameter and length, a wide airway conduit, the absence of a grill in the ventilating orifice, the soft flexible material, and the self-pressurizing cuff [4]. These design features can facilitate safer awake FOB intubation even in morbidly obese patients [5]. Air-Q®sp was easy to insert with a smaller and thinner cuff, a larger view space for aiming the tip of FOB towards the vocal cords, and the largest distance from the mask aperture to the laryngeal inlet compared to others (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

7.0 mm ID TaperGuard™ endotracheal tube inserted into the tube of Air-Q®sp size 3.5 with the red color-coded connector removed.

In conclusion, awake FOB intubation was found to be the safest option in a patient with Ludwig's angina and is a good alternative to Air-Q®sp-assisted orotracheal FOB. We recommend obtaining the full cooperation of the patient and performing a thorough preoperative airway evaluation. Expert airway management taking into account the patient's condition and using a range of resources including awake FOB intubation was successful in this case.

References

- 1.Bross-Soriano D, Arrieta-Gomez JR, Prado-Calleros H, Schimelmitz-Idi J, Jorba-Basave S. Management of Ludwig's angina with small neck incisions: 18 years experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:712–717. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green L. Can't intubate, can't ventilate! A survey of knowledge and skills in a large teaching hospital. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009;26:480–483. doi: 10.1097/eja.0b013e3283257d25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xue FS, Li CW, Liu KP, Sun HT, Zhang GH, Xu YC, et al. Circulatory responses to fiberoptic intubation in anesthetized children: a comparison of oral and nasal routes. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:283–288. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000253032.09962.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schebesta K, Karanovic G, Krafft P, Rössler B, Kimberger O. Distance from the glottis to the grille: the LMA Unique, Air-Q and CobraPLA as intubation conduits: a randomised trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2014;31:159–165. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiraishi T. Awake insertion of the air-Q intubating laryngeal airway device that facilitates safer tracheal intubation in morbidly obese patients. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:1024–1025. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]