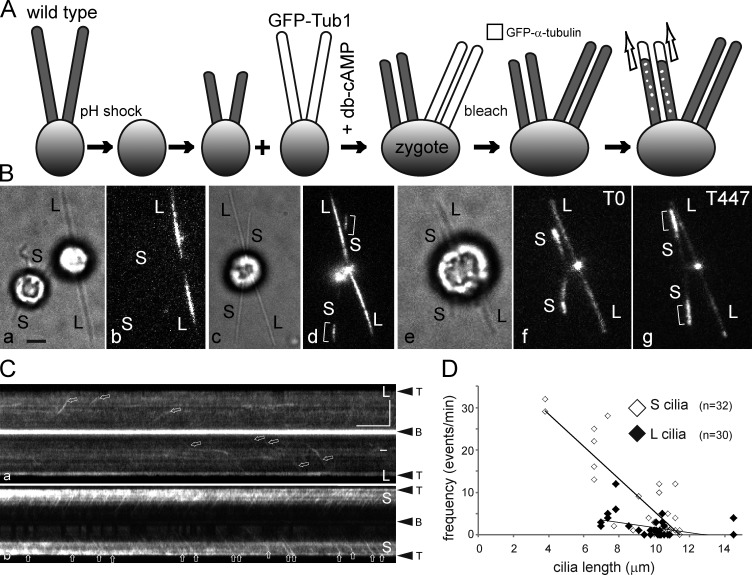

Figure 5.

Cells direct tubulin flux specifically into growing cilia. (A) Schematic presentation of the experimental design. Wild-type gametes were deciliated by a pH shock, allowed to initiate cilia regeneration, and fused to GFP–α-tubulin expressing gametes with full-length cilia. Cell fusion was promoted by adding 15 mM dibutyryl cAMP (Pasquale and Goodenough, 1987). The resulting long-short zygotes will initially possess two short, regenerating cilia and two steady-state, GFP-positive cilia. To analyzed GFP-tubulin transport, all four cilia were photobleached. (B) Bright-field (a, c, and e) and TIRF images (b, d, f, and g) of gametes (a and b) and zygotes (c–g). S, regenerating cilia. L, long flagella derived from the GFP–α-tubulin donor strain. Brackets indicate ciliary segments assembled after cell fusion. Note elongation of short cilia depicted in e–g; the time points (in seconds) are indicated. Bar, 2 µm. (C) Kymograms of the long (L) and short (S) cilia of the zygote shown in B (e–g). Arrows: GFP-tubulin trajectories. Bars, 5 µm and 5 s. (D) Scatter plot showing the frequency of anterograde GFP-tubulin trajectories in wild-type–derived regenerating cilia (S cilia, open diamonds) and GFP-Tub1–derived cilia (L cilia, closed diamonds) of eight long-short zygotes. Mean values were 7.8 ± 10 versus 1.8 ± 2.6 events/min, respectively; P = 0.0016. Some data points with zero transport events and similar ciliary length overlap. See Fig. S4 for a histogram of the data.