Abstract

In developing countries, demand exists for a cost-effective method to evaluate Human Immunodeficiency Virus patients’ CD4+ T-helper cell count. The TH (CD4) cell count is the current marker used to identify when an HIV patient has progressed to Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, which results when the immune system can no longer prevent certain opportunistic infections. A system to perform TH count that obviates the use of costly flow cytometry will enable doctors to more closely follow patients’ disease progression and response to therapy in areas where such advanced equipment is unavailable. Our system of two serially-operated immiscible phase exclusion-based cell isolations coupled with a rapid fluorescent readout enables exclusion-based isolation and accurate counting of T-helper cells at lower cost and from a smaller volume of blood than previous methods. TH cell isolation via IFAST compares well against the established Dynal T4 Quant Kit and is sensitive at CD4 counts representative of immunocompromised patients (below 200 TH cells per µL of blood). Our technique retains use of open, simple-to-operate devices that enable IFAST as a high throughput, automatable sample preparation method, improving throughput over previous low-resource methods.

Keywords: Point-of-Care Testing, CD4 Count, HIV/AIDS, Microfluidics, IFAST

Introduction

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) continues to challenge the global health community, particularly in the developing world. The virus infects immune cells displaying the membrane protein CD4, significantly impacting CD4-positive T-helper (TH) lymphocytes (CD4 cells). As HIV progresses, the number of TH cells declines, compromising the body’s adaptive immune response and increasing its susceptibility to infections. Once the CD4 cell count drops below 200 cells/µL, the patient is diagnosed with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)1. According to the World Health Organization, anti-retroviral therapy (ART) should be initiated when the CD4 count reaches 300 cells/µL1, with the prophylactic intention of preventing further immune suppression and opportunistic infection. However, HIV mutates rapidly and each individual responds differently to ART, necessitating regular evaluation of treatment efficacy and adjustment of therapy to prevent immunological failure. Thus, accurate CD4 count remains a critical clinical measure for tracking disease progression and informing treatment decisions1.

In developed nations, flow cytometry is the gold standard for monitoring CD4 count. HIV progression is monitored in the clinic via nucleic acid tests (RT-PCR) for viral load and flow cytometry for CD4 enumeration. Unfortunately, these methods require expensive equipment and reagents, along with advanced facilities and highly trained laboratory personnel to operate and maintain the systems. Costly maintenance contracts add an additional financial strain on resource-limited clinics2. Since CD4 count is the only surrogate marker for the degree of HIV-induced immunodeficiency, it has been recommended that this test be implemented in preference to viral load measurements when both cannot be given in tandem3. Currently, the cost of CD4+ TH cell enumeration is prohibitive in the developing world as only select hospitals can afford the infrastructure to perform flow cytometry. Reaching patients in outlying and rural areas far from these clinics is difficult, especially since flow cytometry samples must be processed within a few hours of blood collection, and there is often no efficient means of sample transport. Others have proposed microfluidic strategies for obtaining CD4 count, however these methods still frequently require relatively costly and immobile microscope readouts and sophisticated assay setup4–9. The need persists for inexpensive CD4 counts that can reasonably be conducted and analyzed truly at the point-of-care (POC) in low-resource settings.

Previous work has focused on developing a CD4 count suitable for POC use2–4,7–14. The Dynal T4 Quant kit (Invitrogen, Oslo, Norway) isolates TH cells from whole blood via paramagnetic particles (PMPs, magnetic beads) functionalized with monoclonal antibodies. In brief, the kit removes monocytes (which also express CD4 and can confound the count) via anti-CD14 PMPs, then isolates TH cells via anti-CD4 PMPs. The PMP-bound TH cells are then washed and lysed, and the nuclei are colorimetrically-stained or fluorescently dyed and counted on a hemacytometer to yield the patient’s CD4 count. This technique requires little training, no equipment more advanced than a light microscope, and has been successfully demonstrated in several low-resource settings12. Lyamuya et al. compared the Dynal T4 Quant kit against standard flow cytometry and several other low-resource alternatives. Their study found excellent correlation (r = .939) between the Dynal method and flow cytometry, but noted that T4 Quant kit suffers from a laborious manual data collection process14. Other groups share this concern, noting a limit of six or fewer samples per hour1,3,13, but note the T4 Quant kit’s distinctly low cost per test12,13.

Immiscible filtration assisted by surface tension (IFAST) is a sample preparation method that utilizes microfluidic immiscible interfaces to permit rapid magnetic bead-based isolation of analytes ranging from nucleic acids to proteins to whole cells15–20. As shown in Fig. 1a, microfluidic constrictions allow immiscible fluids to form “virtual walls” in horizontally-adjacent wells, without density-driven vertical stacking as occurs in larger scale oil-water interactions. Operation of IFAST is simple: a magnet is applied to the bottom of the device and manipulated to move the analyte-bound PMPs through the immiscible barrier and into another aqueous well, thus utilizing exclusion to separate the analyte of interest from contaminating elements of the sample (e.g. red blood cells, RBCs) (Fig. 1a). Multiple oil/water interfaces can be placed in series to afford multiple “wash” steps that allow removal of contaminants more rapidly than can be achieved in conventional PMP-based isolations16, and additional analytical steps (e.g. cellular staining) can be incorporated into these wells. The purified sample eluted into the final aqueous well is ready for downstream analysis. Recent work on a mock seroconversion assay has shown that IFAST is amenable to high-throughput automation with robotic liquid handlers and that automated operation results in improved reproducibility19.

Figure 1.

IFAST sample preparation device. (a) Schematic representation of the IFAST devices used for CD14 depletion and CD4 isolation. As shown, these devices each contain a total of three oil barriers. The magnet is drawn across the bottom of the device from the input to the output well at a rate of 1–2 millimeters per second. The magnetic beads move with the magnet, carrying along attached cells and excluding unbound cells at the immiscible phase barrier. Supplemental video SV1 demonstrates the isolation process. (b) Photographs of an IFAST being manually actuated with a magnet. (c) Schematic comparison of IFAST CD4 enumeration and Dynal T4 Quant kit workflows.

In the current report, we present an IFAST method optimized for isolating CD4+ TH cells from small samples of whole blood. We have modified the Dynal T4 Quant kit protocol such that both the monocyte depletion and CD4 isolation occur in a pair of IFAST devices. Isolated cells are dyed on-chip with Calcein AM, a small molecule dye metabolized to a fluorescent form by live cells, thus avoiding use of costly and delicate fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies. Our method correlates well with conventional operation of the Dynal T4 Quant Kit and can be read by a simple fluorometer. Importantly, this technique requires considerably less blood sample and reagent volume than conventional methods (50–1000µL blood for flow cytometry collected from venipuncture vs. 125µL blood for T4 Quant Kit vs. ≤ 2.5µL blood for IFAST) and maintains IFAST’s capacity for high throughput operation, making it compatible for the varying patient demand in both regional hospitals and local clinics in the developing world.

Materials and Methods

Devices

IFAST devices were fabricated following previously-described conventional soft lithography techniques21. In brief, master molds were created by exposing SU-8 photoresist (Microchem, Newton, MA) to UV light through patterned photomasks (Image Setter, Madison, WI). Sylgard 184 polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) was mixed 10:1 with curing agent, degassed, poured on the master, and cured for four hours at 80°C. Cured devices were applied to cyclic olefin copolymer backing via conformal contact. The devices included multiple aqueous wash wells to ensure contaminants such as red blood cells were removed.

Blood Samples

Human whole blood samples from anonymous healthy donors were purchased from Valley Biomedical (Winchester, VA). Samples were validated to be HIV-, hepatitis-, and syphilis-free by the supplier before delivery, and were stored in disodium-EDTA anticoagulant at 4°C. Samples were sequentially numbered and processed immediately upon arrival, as extended storage adversely impacts leukocyte populations11,22; however, the supplier’s disease testing and shipping took ≥ 3 days, potentially depressing the CD4 count.

T4 Quant Kit Operation

The T4 Quant Kit was operated as directed by the manufacturer. Briefly, 125µL of whole blood were added to 350µL phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and 25µL of anti-CD14 PMPs in an Eppendorf tube. The mixture was incubated on a rotator at room temperature for ten minutes, and then the tube was placed on a magnetic rack for two minutes to perform monocyte depletion. While on the magnet, 200µL of the supernatant blood were pipetted to a new tube containing 200µL PBS and 25µL anti-CD4 PMPs, incubated, and placed on the magnet rack as above. Following two minutes of magnetic separation, the supernatant was aspirated and discarded. The PMP-bound CD4 cells were then washed in 500µL PBS, magnetically pelleted, and resuspended in 50µL Dynal lysis buffer containing 1:1000 Hoechst 33342 DNA dye (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). After five minutes of lysis, the solution was diluted in 50µL PBS, the PMPs were pulled aside via the magnet, and the solution was added to a hemocytometer and imaged on an Olympus IX81 fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation of the Americas, Center Valley, PA). Cell counts were performed in ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD) and a dilution factor of two was applied to obtain a CD4+ TH cell count per µL of whole blood.

IFAST Operation

First, monocytes were removed from the samples to prevent counting them as CD4 cells. 2.5µL of whole blood were incubated with 5µL anti-CD14 PMPs and 42.5µL PBS with 5mM EDTA, 1% Tween20, and 0.1% w/v bovine serum albumin (BSA) in a microcentrifuge tube at room temperature for 10 minutes. The solution was loaded via pipette into an IFAST input and the remaining wells were filled with 10µL Fluorinert FC40 oil (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 10µL PBS containing 0.01% Tween20 in alternating fashion by pipette. In this report, each oil to aqueous transition constitutes a “wash.” Monocytes were removed by pulling the anti-CD14 PMPs through the immiscible barriers (Fig. 1).

To isolate CD4 cells, half of the remaining monocyte-depleted blood was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube and incubated with 5µL anti-CD4 PMPs and 20µL PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature. Following incubation, the sample was loaded into a new IFAST device and PMP-bound CD4 cells were isolated via the magnet.

A fluorescent intracellular dye was used to image and enumerate captured cells. Calcein AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was diluted 1:200 in PBS containing 0.1% w/v BSA in the aqueous output well (30µL volume) and the cells were incubated therein for 10 minutes before further analysis.

Capture Efficiency

To test isolation efficiency, samples were “re-probed” to confirm that the vast majority of target cells were captured upon a single isolation. The IFAST protocol was modified such that both PMP varieties were run twice in series. The anti-CD14-bound cells from the first incubation were imaged and counted, then the remaining input blood was re-incubated with new anti-CD14 PMPs and another isolation was performed in a another IFAST. This provided two counts of cells bound by the same PMP type, indicating what fraction of target cells went uncaptured in the first isolation. The process was repeated on the same samples with CD4 PMPs.

In order to compare the CD4 counts obtained by the T4 Quant Kit and IFAST, CD4 cells isolated by IFAST were resuspended in the T4 Quant Kit’s lysis buffer, incubated, and imaged as described in the Kit’s protocol, above.

Cell Quantitation

Captured cells were initially counted on-chip in IFAST devices by fluorescence microscopy. PMP-bound cells were re-dispersed in the Calcein AM-containing output well and incubated in the dark for 10 minutes at room temperature. The entire output well was then imaged using a 10× objective lens on an IX70 fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation of the Americas, Center Valley, PA) on an automated stage directed by a custom journal program in MetaMorph® imaging software (Molecular Devices LLC, Sunnyvale, CA). Images were processed via background subtraction and thresholding in ImageJ. The total counts of fluorescent cells in each device were divided by the volume of whole blood inputted to the CD4 isolation (1.25µL) to yield cells/µL.

An inexpensive fluorometer was implemented to distinguish CD4 counts in mock immunocompromised blood. Mock immunocompromised blood was prepared by incubating whole blood with both anti-CD14 and anti-CD4 PMPs simultaneously and isolating the cells in an IFAST device. New whole blood was mixed with this depleted blood to constitute “immunocompromised” blood at several different CD4 counts (e.g., a 50:50 mixture of whole:depleted blood has 50% of the whole blood’s CD4 count). CD4 cells were isolated from these mixtures according to the IFAST protocol above and analyzed in a Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PMP-bound cells were re-suspended in PBS containing Calcein AM in Qubit® microtubes (200µL total volume) and incubated for 10 minutes in the dark at room temperature. Fluorescence was quantified by using a 470nm LED from the Qubit®’s dsDNA quantification protocol. Total relative fluorescence units (RFU) readings were collected in triplicate for each of three samples per blood dilution. A linear response between inputted whole blood fraction and detected fluorescence was obtained, even at low CD4 counts.

Results

Sample Purity

CD14 & CD4 Re-depletion

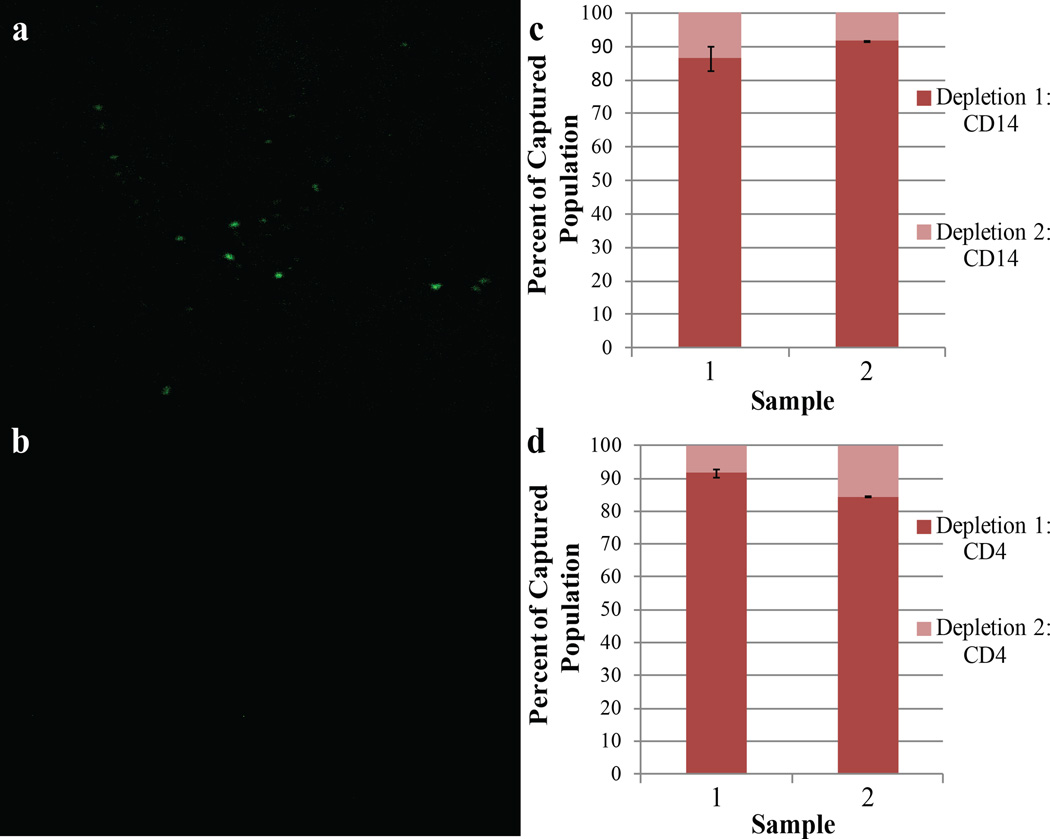

In order to ensure that cells from each population were not left behind, we “re-probed” the whole blood input with PMPs following both steps of the CD4 isolation. Dyeing and counting these cells allowed approximation of what fraction of each cell type remained uncaptured after a single isolation. Fig. 2 shows fluorescence images of captured CD4 cells following CD14 depletion. The vast majority of cells observed in both isolations reside in the initial depletion; < 15% of the total populations were counted in the re-probe fraction, as demonstrated in samples from two individual donors (Fig. 2c, Fig. 2d). This result suggests that IFAST successfully depletes the sample of contaminating CD14+ monocytes before CD4 isolation and that the CD4 count is accurate, since few cells are captured upon repeated PMP incubation.

Figure 2.

CD14 and CD4 capture efficiency. (a) 10× objective lens image of the extracted CD4+ cells stained in Calcein AM following isolation with CD4 PMPS. (b) A 10× objective image of the CD4+ yield of the second CD4 isolation; considerably fewer cells than isolated by the first. The image from the second depletion was taken from the same location as the initial depletion. Cell counts were obtained by ImageJ analysis for two distinct donors in triplicate for both CD14 (c) and CD4 (d) re-depletion tests. The plot shows percentages of the total captured cells counted in each fraction. Error bars indicate one standard deviation of the percentage of cells captured in the second isolation.

CD4 Counts

Dynal T4 Quant Kit Hemocytometer Approach and IFAST Comparison

Across multiple independent studies, the Dynal T4 Quant Kit has been previously shown to accurately count CD4 cells with a Spearman correlation coefficient r of ≥ 0.89 when compared to the results obtained by the current standard, flow cytometry3,12–14. The Kit requires that the isolated cells be incubated in a lysis buffer containing a nuclear stain then counted in a hemacytometer on a microscope. Enumeration of IFAST-isolated CD4 cells via the Kit’s imaging protocol enabled fair comparison of the two methods. IFAST provided counts consistent with the Kit for multiple patients, indicating that IFAST successfully captures and enumerates the relevant CD4+ populations (Fig. 3). The CD4 counts obtained in Fig. 3 are lower than would be expected for healthy adult donors, however, the blood used in this work was disease-tested and processed for three days before CD4 counting. Previous reports suggest that CD4+ TH cell counts decline during storage, potentially accounting for the lower than anticipated counts observed here 11.

Figure 3.

Comparison of cell count obtained by both the Dynal T4 Kit and IFAST for two donors. The methods demonstrate agreement in three or more trials. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

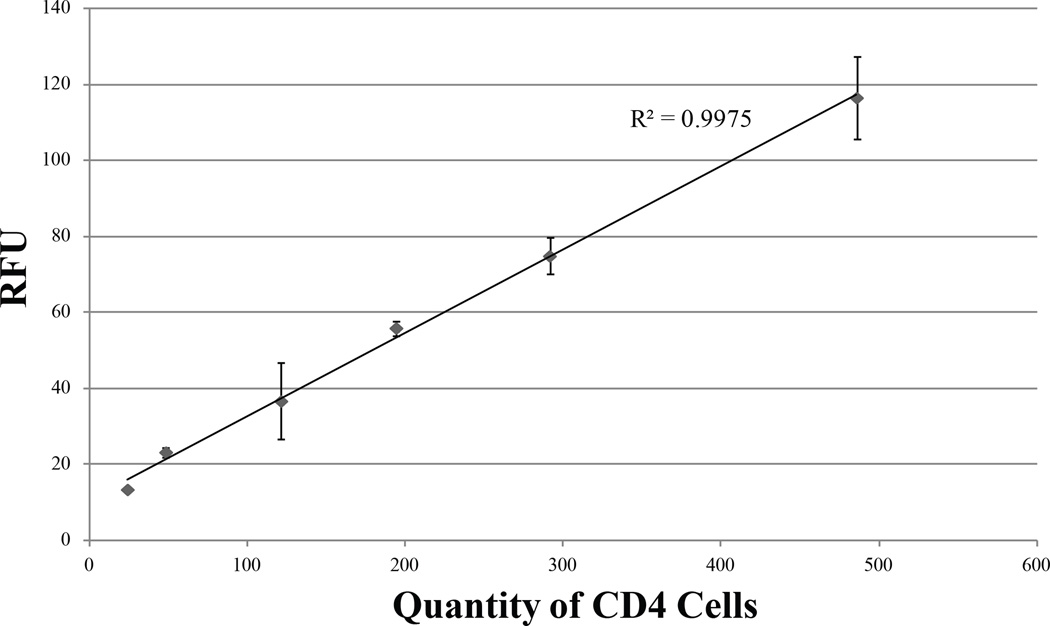

Fluorescent Readouts

While microscope-based fluorescent imaging may be unrealistic for the developing world, a simple fluorescent readout from a battery-powered device for CD4 enumeration could provide a truly POC solution for resource-constrained HIV diagnostics. The Qubit® 2.0 is a small fluorometer: slightly larger than a human hand, with 9V DC and maximum 1.33A. TH cells isolated and dyed in IFAST were analyzed by a Qubit® to determine if such a method can distinguish low CD4 cell populations in a patient suffering from AIDS. As the blood used in this work was obtained from healthy, HIV-negative individuals, the CD4 count range can be predicted to be above the range anticipated in AIDS23. To test the sensitivity of this fluorescence readout at CD4 counts relevant to different stages of HIV, depleted blood at various levels of CD4 cells was prepared to determine the linearity of the Qubit®’s response at low CD4 count. From these samples, isolated TH cells (total volume 30 µL) that had been dyed in Calcein AM for ten minutes were transferred into Qubit® microtubes containing 170µL PBS and read on the instrument. Fig. 4 depicts that the RFU readout is highly linear and consistent, with a limit of detection under 100 CD4+ cells. This result suggests that a handheld, battery-operated fluorometer could be coupled with IFAST purification of CD4+ cells from only a finger prick’s worth of blood to rapidly deliver CD4 count at the point of care. Utilizing such a method to analyze samples on-site will alleviate difficulties associated with sample storage and transportation while providing test results to patients in under an hour.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence readouts from one serially-diluted blood sample read via a Qubit® fluorometer. Whole blood was mixed with both anti-CD14 and anti-CD4 beads to simultaneously remove all CD4+ cells via IFAST, constituting CD4-depleted blood. Small amounts of whole blood were diluted in this CD4− blood such that the resultant mixture was similar to samples from immunocompromised patients. All samples were then subjected to monocyte depletion and CD4 isolation in IFAST before analysis in the Qubit® Data is plotted in terms of actual cell count per µL based on Sample 4’s counts obtained by the validated Dynal Kit protocol (Fig. 3). Error bars represent one standard deviation of three measurements.

Discussion

Here we have presented an exclusion-based method for CD4+ TH cell isolation coupled with a simple fluorescence readout for use in POC diagnostics. Our technique employs magnetic beads to efficiently deplete blood of contaminating monocytes and capture CD4 cells (Fig. 2). CD4 enumeration via IFAST compares favorably to the established Dynal T4 Quant Kit (Fig. 3). Though blood donors were HIV-negative, both patients analyzed in this study registered slightly lower CD4 counts than expected for healthy adults (>500 cells/µL expected). This may be due to protracted sample acquisition, processing, and transportation, which presently takes ≥ 3 days. Extended storage is thought to diminish lymphocyte counts11, however, we anticipate being able to run samples immediately after blood draw in future work. In order to circumvent cumbersome manual counting via microscope, we have validated that a compact, inexpensive Qubit® fluorometer responds linearly with cell number to fluorescent Calcein AM dye (Fig. 4) in samples comparable to immunocompromised blood. Our method preserves IFAST’s capacity for high-throughput automation and avoids the use of costly equipment and reagents, paving the way for a truly point-of-care CD4 count test. In future work, both monocyte depletion and CD4 isolation will be performed in a single, bi-directional IFAST device, reducing pipetting steps. Conceivably, the fluorescent readout could also be incorporated into an automated process, as this process requires only an LED and a detector.

CD4 testing remains a critical component of HIV care. Increasing access to regular CD4 counts in resource-poor settings such as Sub-Saharan Africa is imperative - a single Ugandan clinic currently reports conducting nearly 31,000 CD4 enumerations per year24. However, the current method relies on use of a flow cytometer, an expensive piece of equipment that requires specialized personnel. Lowering the cost of each test, enabling procurement of test results in remote settings, and simplifying analysis will improve treatment and management of HIV in low resource areas. Presently, untreated patients should ideally receive CD4 counts every 3–6 months to track when prophylactic ART needs to be initiated, and in treated patients with suppressed viral loads yearly tests are recommended25. Low income limits access to care in nations like Uganda, and HIV patients may face even greater financial strain resulting from missed work, etc.

Reducing the cost of CD4 testing is one of the largest hurdles in improving access to this test. In 2009/2010, average household income in Uganda totaled roughly 300,000 UGX per month - equivalent to approximately $145 USD per month at the contemporary exchange rate, but ranged as low as $56 USD per month in rural northern Uganda26. Flow cytometers require substantial financial investment, with initial capital costs > $100,000 USD, and also necessitate further expenses such as maintenance contracts, sophisticated laboratory environments, and highly skilled labor. Additionally, remotely-located cytometers may experience extended periods of disuse while awaiting maintenance. Newer, cheaper technologies such as the Alere PIMA system (which also uses a fingerprick of blood) have entered the global health market. However, many similar limitations still apply, namely high cost per test and low throughput ($9 USD reagents per test, theoretical maximum of 15 tests per day)27. The Dynal T4 Quant Kit has shown excellent correlation to flow cytometric quantitation of CD4 cells in multiple studies3,10,12–14. Previous research demonstrates that the Dynal T4 Quant Kit reduces the reagent cost of a CD4 enumeration to as little as $3 USD or even $1 USD (with modifications) per test as opposed to $25 USD for a flow cytometry test10,12. However, these methods still require manual microscopic readouts, rendering them inherently non-portable, introducing subjectivity to cell quantitation, retaining relatively large capital costs, and severely limiting throughput1. In short, the Kit is both financially and practically unrealistic as a truly point-of-care diagnostic solution for resource-constrained and remote settings.

An ideal POC CD4 test is easily administrable in both regional hospitals and in local clinics. It should be rapid, allowing quick turnaround from sample collection to test result, and be minimally-invasive to the patient. Our microfluidic IFAST platform addresses the limitations of previous magnetic bead-based CD4 counts while preserving the performance and low cost per test that make the T4 Quant Kit desirable for POC diagnostics and requiring a small sample, easily obtained via finger-prick. Additionally, IFAST’s amenability to automation has been previously shown on a mock seroconversion assay where operation by a simple robot vastly reduced variability compared with human operators19. Our current modifications to IFAST do not compromise the flat, open layout and simplicity that enable facile automation, and we anticipate that our fluorescent readout could easily be incorporated into an automated system at low cost. In cases where automation is unnecessary (e.g. low numbers of patients, especially remote settings), simple manual operation and a small, portable readout allow IFAST to address a critical need in POC diagnostics. The Qubit® 2.0 fluorometer utilized in this work is inexpensive, with < $2,000 USD in capital costs (Life Technologies product Q32866)28. Based on our method’s five-fold reduction in reagent use and minimal equipment, we estimate that an IFAST CD4 count can be administered for a total reagent cost of < $1.50 USD per test (supplemental figure S1). An initial startup cost of $2,000 USD is required for the purchase of the Qubit®; however this remains lower than capital expenses of other technologies, and may well be lowered with “home-built” fluorometers (which could potentially be integrated into an automated system).

A POC solution to CD4 counts is one that can be delivered on-site. As flow cytometers reside only in well-resourced areas, samples need to be transported off site to another location, possibly days away 12. Proper storage is not guaranteed and samples may be easily lost or mishandled along the way. Even upon analysis, there is no way to ensure that the test results will make it back to the patient, since the patient may never return to the clinic – up to 40% of HIV patients in sub-Saharan Africa do not receive their CD4 counts27. Our method of exclusion-based CD4 cell isolation and enumeration is easily transportable, and we have validated that IFAST functions in climates as extreme as 45°C and 95% relative humidity, harsher than would be found in POC environments (unpublished data). Very small blood samples (< 5µL) can be taken and analyzed on-site easily with our POC solution. From blood draw to readout, our test can be completed in ≤ 40 minutes, including a total of three 10 minute incubations. This rapid turnaround will improve patient receipt of test results and encourage counseling and treatment decisions to occur during a single visit to the clinic. Providing the patient with immediate information through on-site sample analysis and result disclosure will empower doctors and patients to more closely monitor HIV progression in low resource settings, enabling improved care by lowering the economic barrier to CD4 counts and preventing loss of communication between testing and follow-up counseling. With more affordable, frequent CD4 tests, clinicians will be able to make better-informed decisions regarding ART initiation and long-term efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The Authors wish to thank Dr. Frank Graziano for his advice and guidance in this work.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Grand Challenges in Global Health program.

A.H. is funded by the National Institutes of Health Chemistry-Biology Interface Predoctoral Training Program, (5T32GM008505-20).

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials are available online.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

S.B. and D.B. have equity in Salus Discovery LLC.

References

- 1.Laboratory Guidelines for enumerating CD4 Lymphocytes in the context of HIV/AIDS. New Dehli: WHO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balakrishnan P, Dunne M, Kumarasamy N, et al. An Inexpensive, Simple, and Manual Method of CD4 T-Cell Quantitation in HIV_Infected Individuals for Use in Developing Countries. JAIDS. 2004;36:1006. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200408150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crowe S, Turnbull S, Oelrichs R, et al. Monitoring of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in Resource-Constrained Countries. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:S25. doi: 10.1086/375369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez WR, Christodoulides N, Floriano PN, et al. A Microchip CD4 Counting Method for HIV Monitoring in Resource-Poor Settings. PloS Med. 2005;2:0663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou Q, Liu Y, Shin D-S, et al. Aptamer-Containing Surfaces for Selective Capture of CD4 Expressing Cells. Langmuir. 2012;28:12544–12549. doi: 10.1021/la2050338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes D, Morgan H. Single Cell Impedance Cytometry for Identification and Counting of CD4 T-Cells in Human Blood Using Impedance Labels. Anal Chem. 2010;82:1455. doi: 10.1021/ac902568p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng X, Irimia D, Dixon M, et al. A microchip approach for practical label-free CD4+ T-cell counting of HIV-infected subjects in resource-poor settings. JAIDS. 2007;45:257. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng X, Gupta A, Chen C, et al. Enhancing the performance of a point-of-care CD4+ T-cell counting microchip through monocyte depletion for HIV/AIDS diagnostics. Lab Chip. 2009;9:1357. doi: 10.1039/b818813k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thorslund S, Larsson R, Bergquist J, et al. A PDMS-based disposable microfluidic sensor for CD4+ lymphocyte counting. Biomed Microdevices. 2008;10:851. doi: 10.1007/s10544-008-9199-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bi X, Gatanaga H, Tanaka M, et al. Modified Dynabeads Method for Enumerating CD4+ T-Lymphocyte Count for Widespread Use in Resource-Limited Situations. JAIDS. 2005;38 doi: 10.1097/00126334-200501010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briggs C, Machin S, Muller M, et al. Measurement of CD4+ T cells in point-of-care settings with the Sysmex pocH-100i haematological analyser. Int J Lab Hematol. 2007;31:169. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2007.01017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diagbouga S, Chazallon C, Kazatchkinec MD, et al. Successful implementation of a low-cost method for enumerating CD4+ T lymphocytes in resource-limited settings: the ANRS12-26 study. AIDS. 2003;17:2201. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200310170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Didier JM, Kazatchkine MD, Demouchy C, et al. Comparative Assessment of Five Alternative Methods for CD4+ T-Lymphocyte Enumeration for Implementation in Developing Countries. JAIDS. 2001;26:193. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200102010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyamuya EF, Kagoma C, Mbena EC, et al. Evaluation of the FACScount, TRAx CD4 and Dynabeads methods for CD4 lymphocyte determination. J Immunol Methods. 1996;195:103. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strotman LN, Lin G, Berry SM, et al. Analyst. 2012;137:4023. doi: 10.1039/c2an35506j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berry SM, Alarid ET, Beebe DJ. One-step purification of nucleic acid for gene expression analysis via Immiscible Filtration Assisted by Surface Tension (IFAST) Lab Chip. 2011;11:1747. doi: 10.1039/c1lc00004g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berry SM, Strotman LN, Keuck JD, et al. Purification of cell subpopulations via immiscible filtration assisted by surface tension (IFAST) Biomed Microdevices. 2011;13:1033. doi: 10.1007/s10544-011-9573-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berry SM, Maccoux LJ, Beebe DJ. Streamlining Immunoassays with Immiscible Filtrations Assisted by Surface Tension. Anal Chem. 2012;84:5518–5523. doi: 10.1021/ac300085m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berry SM, Regehr KJ, Casavant BP, et al. Automated Operation of Immisscible Filtration Assisted by Surface Tension (IFAST) Arrays for Streamlined Analyte Isolation. JALA. 2013;18:206. doi: 10.1177/2211068212462023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moussavi-Harami F, Annis DS, Ma W, et al. Characterization of Molecules Binding to the 70K N-Terminal Region of Fibronectin by IFAST Purification Coupled with Mass Spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:3393–3404. doi: 10.1021/pr400225p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia Y, Whitesides G. Soft Lithography. Annu Rev Mater Sci. 1998;28:153. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Personal Communication, UWCCC Flow Cytometry Lab. 2013. Jun,

- 23.Bofill M, Janossy G, Lee CA, et al. Laboratory control values for CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes. Implications for HIV-1 diagnosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;88:243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb03068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.2010 Annual Report. Uganda: Joint Clinical Research Centre; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. United States: Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uganda National Household Survey 2009/2010. Uganda: Uganda Bureau of Statistics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson B, Schnippel K, Ndibongo B, et al. How to Estimate the Cost of Point-of-Care CD4 Testing in Program Settings: An Example Using the Alere PimaTM Analyzer in South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. [Accessed June 25, 2013];Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer. http://products.invitrogen.com/ivgn/product/Q32866.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.