SUMMARY

The women, men, and transgender persons who sell sex globally have disproportionate risks and burdens of HIV, in low, middle and high income country settings, and in concentrated and generalized epidemic contexts. The greatest HIV burdens continue to be among African women sex workers. Worldwide, sex workers continue to face reduced access to needed HIV prevention, treatment, and care services. Legal environments, policies and policing practices, lack of funding for research and HIV programming, human rights violations and stigma and discrimination continue to challenge sex workers’ abilities to protect themselves, their families, and their sexual partners from HIV. These realities must change for the benefits of recent advances in HIV prevention and treatment to be realized and for global control of the HIV pandemic to be achieved. Effective combination prevention and treatment approaches are feasible, can be tailored for cultural competence, can be cost-saving and can help address the unmet needs of sex workers and their communities in ways that uphold their human rights. To address HIV among sex workers will require sustained community engagement and empowerment, continued research, political will, structural and policy reform and innovative programming. But it can and must be done.

Keywords: sex work, MSM, Transgender women, HIV prevalence, cost effectiveness, molecular epidemiology, human rights

INTRODUCTION

Women, men, and transgender persons who engage in sex work face disproportionate burdens of HIV, HIV risks and lack of access to essential services. This is true in low, medium and high income countries, in concentrated HIV epidemics and in generalized ones.1,2 We must do better and we can. Improved efforts by and for people who sell sex can no longer be seen as peripheral to the achievement of universal access to HIV services and to eventual control of the pandemic.

Sex workers (SW) are an enormously diverse group working in a wide array of contexts—some in safety—and some in difficult and dangerous settings. Shannon, et al, in this series, demonstrate how structural determinants can heighten risk for HIV, or markedly decrease it.1,2 While governments and security entities, most notably the police, have crucial roles to play in helping to establish environments which support public health goals of safety and HIV risk reduction—they often remain impediments to protection.3 Widespread use of condom carriage as evidence of sex work by police is a vivid reminder of how life-threatening bad public policy can be.

The current moment is one of great optimism in HIV prevention. Breakthroughs in HIV treatment, prevention science, program implementation and human rights realization have led to assertions that “an AIDS free generation” is possible.4 Advances in HIV prevention science relevant to SW were reviewed by Bekker, et al,5 for women, by Baral, et al,6 for men, and by Poteat, et al,7 for transgender women, and show considerable promise. Uptake, adaptation, and successful use of these innovations by sex workers are critical steps for the future. Yet however far the global response to HIV can move toward the goal of universal access to these new interventions, Decker and Kerrigan put forth in their papers that without a rights-based framework for HIV interventions and participation, engagement, and empowerment of sex workers, HIV control will remain elusive.3,8

In reviewing the evidence about HIV among SW, we identified striking trends and problematic gaps. For the first 2 decades of HIV, female SW were central to many HIV research and program efforts. Studies of HIV in women routinely were either conducted within female SW populations or included their substantial numbers.9 Community-based and led intervention efforts, including the Sonagachi Program and other efforts in Bangladesh, Thailand, Cambodia, Kenya, the Gambia and Brazil demonstrated impressive reductions in HIV risk, and in other sexually transmitted infections (STI), prior to the advent of the antiretroviral therapy (ART) era.8,10,11

Several events and trends markedly changed this situation and slowed further progress. Controversy over the ethics of the first oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) trials in women, which had been designed for female SW in Cambodia in 2004 and in Cameroon in 2005, halted both studies. Many researchers moved toward less contested populations.12 The advent of the 2003 “Prostitution Pledge” policy requirement for U.S. Federal (PEPFAR) funding reduced programmatic engagement with SW in some settings.3,13,14 This has been associated with reduced financing of HIV programs for SW, particularly programs which funded SW-led organizations.15 Finally, the very high HIV incidence among women in Southern Sub-Saharan Africa in 2001–2005, meant that HIV studies which required HIV sero-conversion endpoints (microbicides, HIV vaccines, PrEP)) could be conducted among the general population of reproductive aged women, markedly reducing the necessity of recruiting SW. These trends led to a challenging new situation: we have a tremendous increase in efficacious HIV prevention tools and approaches—yet none of these advances, have specifically been investigated among SW. Adaptation of these tools, and assessment of SW interest and self-efficacy in their use, remains work undone in 2014. Table 1 sets forth a research agenda to address these gaps.

Table 1.

Research Agenda for Sex Workers and HIV

| Question | Study | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | ||

|

| ||

| How prevalent is HIV in SW? How common is undiagnosed HIV infection? | HIV seroprevalence and testing surveys | Must be voluntary, use newer methods (RDS, VTS) |

|

| ||

| What is HIV incidence in SW? | Cross-sectional or prospective studies | Next generation recency assays |

|

| ||

| Basic Sciences | ||

|

| ||

| What formulations of vaginal and rectal microbicides will be acceptable, safe, and efficacious for SW? | Phase I and II trials need to include SW in sufficient sample size for stratified analyses | |

| What new oral/injectable PrEP agents will be acceptable, safe, and efficacious for SW? | Phase I and II trials need to include SW of all genders | |

|

| ||

| Promoting Optimal Care | ||

|

| ||

| How do we optimize access to care for SW? | Continuum of Care and implementation science studies for SW | Stand alone vs integrated services, community led vs community engaged |

| Stigma reduction interventions in health care settings | ||

| Novel adherence studies | Community mobilization interventions could be adapted to adherence support | |

| Human Rights: Impact on successful prevention and treatment | Integration of violence, discrimination, and other human rights measures into SW studies | Violence and broader dimensions of trauma shown to compromise adherence and treatment responses |

| Trauma-informed care | ||

|

| ||

| HIV Prevention | ||

|

| ||

| What combinations of HIV preventive interventions will reduce HIV incidence for SW? | Testing feasibility, acceptability, of prevention packages, trials of efficacy | Resources for SW specific RCTs may be limited |

| What are the best methods to assess combination prevention? | Modeling studies, community-participatory research | |

| What new interventions may hold promise for SW? | Next generation HIV vaccines | Planned WRAIR trial will study MSM in Thailand, may include MSW, TGSW |

|

| ||

| Structural Change | ||

|

| ||

| Structural interventions can reduce HIV risks and increase HIV access for SW? | Structural determinants (risks and protective) studies | Many studies may not have HIV outcomes, but measure changes in violence, safety, access to care |

| Ending impunity for crimes and abuses | Impact of decriminalization on health outcomes | Little is known about changing contexts of impunity to accountability |

| Police, violence prevention, community empowerment interventions | ||

THE GLOBAL BURDEN OF HIV AMONG SEX WORKERS

Estimates of the global numbers of SW and their global HIV burden have been challenged by limitations in surveillance, research methodologies and available data. Baral, et al, conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of HIV prevalence data among female SW in low and middle income countries through June 2011.2,9 Data were available from 50 countries, and included HIV data on 99,878 adult women. Overall HIV prevalence was estimated at 11.8% (95% CI 11.6–12.0), with highest burdens found in Sub-Saharan Africa, 36.9% (95% CI 36.2–37.5) and in Eastern Europe, 10.9% (95% CI 9.8–12.0). Comparing these burdens with women of reproductive age in the same populations yielded a pooled global odds ratio of 13.5% (95% CI 10.0–18.1).

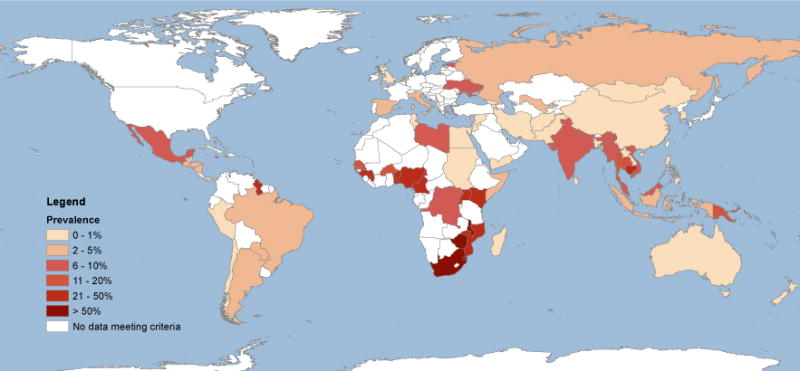

We expanded these data to include high-income countries and updated prevalence estimates for low and middle-income countries through June 20, 2013. Figure 1 shows the global burden of HIV among female SW by 2013 from 79 countries (n= 437,025 women). [Online Appendix 1, Table 1 shows the meta-analysis by region and country economy level.] Sub-Saharan Africa remains the highest burden region with a combined HIV prevalence of 29.3% (95%CI: 25.0 – 33.8%). Countries with over 50% of SW living with HIV are all in southern Africa. Differences in HIV prevalence across economic strata are marked but may be biased by lack of data in high-income countries; neither the U.S. nor Canada collect HIV surveillance data on SW.

Figure 1.

Global burden of HIV infection among adult women sex workers, 2013.

(References for Figure 1 are in the Online Appendix 1)

The high HIV burdens among SW globally, particularly in southern Africa, underscore the need for tailored interventions for SW living with HIV. While all SW need access to condoms, education, STI care and other basic services, ART access for those living with HIV is a treatment and prevention priority.

Prüss-Ustün, et al, recently reported a population attributable fraction (PAF) analysis of the estimated proportion of HIV among women and of the number of HIV deaths among women attributable to sexual transmission in sex work.16 They estimated that globally some 15% (11.5–18.6) of HIV infections among women in 2011 were attributable to sexual transmission in sex work, with the highest proportions in Sub-Saharan Africa (17.8%). Recent estimates of the proportion of new HIV infections within the last year that were due to sexual transmission in sex work include nearly one third of new infections in Ghana, 14% in Kenya, and 10% in Uganda.17–19 A microsimulation study further demonstrated a reduction of incident HIV infection among the total population in Kisumu, Kenya by 66% (54–75%) over 20 years with the removal of transmission in sex work.20

For male SW (MSW), the data are sparse. As of 2011, 51 countries provided data on the burden of HIV among MSW to UNAIDS.6 Four countries reported HIV prevalence over 25%, 12 between 12.5 and 25% and 35 reported HIV prevalence among MSW of under 12.5%.

Global data on the burden of HIV among transgender (TG) sex workers is also limited. One meta-analysis of data from 14 countries found that TG female SW bore a higher burden of HIV (27% prevalence) than other TG women (15%), male SW (15%), and female SW (5%). A recent report from Argentina found TG SW to be the most burdened of any group, with 33.9% HIV prevalence and 11.3/100 PY incidence.21 TG women and TG female SW are often included research as male (MSM) or female SW. Results stratified by TG status are rarely available, limiting understanding of HIV epidemiology or intervention effects. Very high HIV burdens among TG women argue for urgent action in research and interventions.

CALLS TO ACTION

The Role of Structural Determinants

In the epidemiology paper of this series, we review the global epidemiology of HIV among women SW and the extent to which epidemiology considers structural determinants (factors such as laws, migration, stigma; community organization; social, policy, economic and physical features of the work environment), alongside partner/dyad, behavioral and biological factors in HIV transmission.1 We then model the potential course of HIV epidemics and potential reduction of infections through structural change in three epidemiologic settings, high and medium prevalence, concentrated epidemics (India, Canada) and heavy HIV burden settings (Kenya).

Coverage and equitable access to condoms, ART and HIV prevention for SW continues to lag. In heavy HIV burden countries, such as Kenya, where access remains low and ability of SW to organize has been limited by criminalization, stigma and funding gaps, enhanced ART coverage of the SWs and client populations to meet new WHO guidelines (CD4<500) could avert 34% of HIV infection among SWs and clients if met with structural support (e.g. reduction of stigma and discrimination). Even modest coverage of peer/SW-led outreach and support could avert a further 20% of infections among SWs and clients over the next decade. These results support calls for multi-pronged structural and community-led interventions that substantially reduce HIV burden and promote human rights.

Our review and modeling points to the critical need for macro-structural changes (e.g. decriminalization of sex work; addressing migration, stigma) and the work environment features (e.g. reductions/elimination of violence, police harassment, implementation of supportive venue-based policies and practices) they engender as critical to stemming HIV epidemics among SWs and clients. In settings such as Kenya and Canada where sex work is criminalized and sexual violence against SW (by clients, police, partners, strangers) remains endemic, elimination of sexual violence alone could avert 17–20% of HIV infections among SW and clients over the next decade. Access to safer work environments (e.g. venues with supportive policies and practices on violence, HIV; access to condoms) could substantially shift the course of epidemics. Decriminalization of sex work could avert the largest percentage of HIV infections among SWs and clients (33–46%) over the next decade, through iterative effects on violence, police harassment, and safer work environments and HIV transmission pathways.

Prevention

Reducing the HIV transmissions associated with sex work and making sex work safer both for workers and clients are key components to achieving universal prevention access.22 Bekker et al5 describe an impressive array of prevention modalities that can be combined and applied to reduce risk of HIV acquisition in female SW populations globally. In this era of biomedical advances, including topical and oral ARV based PreP and earlier antiretroviral treatment as prevention, it is critical that these are additive, voluntary, and not at the cost of established prevention modalities.23 Community empowerment programs such as Sonagachi24 and others25 have demonstrated the effectiveness of SW-led, rights based programs on a range of HIV-related prevention outcomes—though not HIV incidence—and these approaches can serve as the essential platforms for adaptation and uptake of the next generation of prevention approaches.5,26,27 These are occupational health approaches, which recognize sex work as work, and that many persons will continue to sell sex, and that reducing HIV risks and exposures is a key goal.10 Model simulations suggest that condom promotion and distribution in South Africa have already reduced HIV incidence in SW and their clients by more than 70%. Under optimistic assumptions, voluntary access to PrEP for SW together with ‘test and treat,’ could further reduce HIV incidence in South African female SW and theirclients by 40% or more between 2015 to 2025.5 Effectiveness of biomedical ART-based interventions have approximately >90% protection against transmission if used consistently.28 The great value to individual health of treatment with ART is clear, in terms of reductions in individual morbidity and mortality, and is equally cost-effective. Earlier effective treatment at community levels will also prevent further transmission of HIV to SW by reducing the pool of potentially infectious clients.29 Given that scale-up of coverage will be challenging, there is a need to ensure availability and accessibility of other promising approaches. Male circumcision may also reduce female SW risks for acquisition by reducing the number of men with HIV infection at community levels, although this hypothesis has not been formally investigated. Carefully adding these approaches to tailored prevention packages that recognize and support safe workplaces and respect communities will go far in reducing HIV infection among SW.

Community-Empowerment Responses

Kerrigan, et al,8 report that community empowerment-based responses to HIV are significantly associated with reductions in HIV and STI outcomes and increases in consistent condom use. The systematic review found that community empowerment approaches among SW were associated with reductions in HIV among SW (OR: 0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.52–0.89), gonorrhea (OR: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.46, 0.82), chlamydia (OR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.57, 0.98), and high-titre syphilis (OR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.41, 0.69), and were associated with increased consistent condom use with clients (OR: 3.27; 95% CI: 2.32, 4.62).

Their review, which examined both the peer-reviewed and practice-based evidence from SW-led initiatives, documented formidable barriers to implementation and scale-up, of community empowerment approaches despite the growing evidence of its effectiveness. Challenges, include regressive international discourses and funding constraints, national laws criminalizing sex work, and intersecting social stigmas, discrimination and violence including those related to occupation, gender and HIV status. These findings underscore the need for social and political change related to the recognition of sex work as work.

Human Rights and the Law

A rapidly growing evidence base confirms that human rights violations increase HIV vulnerability and undermine effective prevention.3

Punitive laws create significant barriers in accessing justice, creating a climate of impunity that fuels abuses by police and non-state actors alike. Many rights violations against SW represent gross misinterpretations of policy. Physical and sexual abuse by police, including rape in detention, are well outside international law. Even when lawfully implemented, punitive laws preclude health and safety measures and often result in SW being incarcerated or detained, including in “rehabilitation” centres, without access to treatment or prevention. HIV prevention and treatment for SW requires laws, policies and a social climate that enable their human rights. Furthermore, HIV-interventions themselves must abide by human rights guidelines and policies, programs and practices that are coercive or discriminatory, such as mandatory or forced testing or denial of care must be ended.

Recent policy shifts as well as innovative programming suggest promise for the future in a rights-based HIV response. Shifts toward full decriminalization, as seen in New Zealand, have improved human rights for SW, including the right to health.3

Male Sex Workers

Risks for HIV acquisition have been reported at multiple levels for MSW including the efficient transmission of HIV in anal intercourse, high numbers of sexual partners, large and non-dense sexual networks, and compounded intersectional stigmas.6 Risk reduction for these men is impeded by laws criminalizing sex work, homosexual acts or persons, limited access to HIV prevention and treatment, and HIV non-disclosure. Addressing the complex needs of these men necessitates synergizing laws with public health policy so that available HIV prevention and treatment may be accessed by MSW; improving the surveillance of HIV; characterizing context-specific HIV risks; and providing comprehensive HIV prevention, treatment and care programs. Increasing access to basic prevention technologies, including condoms and condom compatible-lubricants is necessary, but will likely be insufficient. Combination HIV prevention programs for MSW which address the biological drivers of HIV infection, including the strategic and tailored use of anti-retroviral agents including PEP, PrEP, and rectal microbicide formulations, will likely be necessary for HIV prevention success. Ensuring high coverage of HIV testing services with active linkage to CD4 testing, ART initiation, and retention services are core components to ensure optimal health outcomes and to reduce HIV transmission.

Transgender Sex Workers

TG sex workers face unique vulnerabilities to HIV.7 Globally, social acceptance of TG women is heterogeneous –ranging from cultural acceptance to social stigma and criminalization. Stigmatization and criminalization of “cross dressing”, perceived homosexuality, as well as SW status, can create intensely hostile environments for TG SW. Challenges related to legal identities often limit access to HIV services and other care. There is a paucity of evidence-based HIV prevention interventions that have been evaluated among TG SW and none that address structural drivers. Better quality research and surveillance are needed that clearly disaggregate TG women SW from MSM, female SW, and other TG women. In Sub-Saharan Africa and Eastern Europe/Central Asia where there is no data, researchers should engage and collaborate with local TG communities to fill this gap. Mathematical modeling of data from distinct settings in San Francisco and Peru demonstrates that even modest improvements in coverage of biomedical interventions may effect a 50% reduction in HIV incidence within 10 years. Rapid implementation of sustainable, community-led, combination prevention strategies that address social, interpersonal, and individual risks for HIV and integrate gender care into HIV services are urgently needed.

DIVERSITY AND COMMUNALITY

The great diversity of SW and of sex work settings, contexts, and work environments is a challenge for the optimization of HIV services. While burdens of HIV infection in SW generally reflect, albeit at higher prevalence levels, the HIV burdens in the populations of which they are a part,2 SW do share some communalities that transcend context and may require novel approaches to HIV prevention and treatment.

Multiple Partnerships, Antiretroviral Coverage and Viral Load among Sex Workers

In high HIV prevalence networks, even modest risks can yield high probabilities of infection.30 It is now clear that the proportion of HIV-infected persons treated or untreated with ART plays critical roles in individual risks for HIV acquisition.31 Sexually active persons in networks with high viral load and low ART coverage are at higher risk for HIV infection.31 For individuals in serodiscordant relationships, earlier initiation of ART is effective HIV prevention.32 But for those with multiple partners, who are likely to encounter persons at varied stages of HIV infection (acute, recent, and established, diagnosed and not, treated and not) the population levels of these parameters may be critical. This may help explain why women who sell sex in settings with high rates of HIV infection and low treatment coverage, as in Southern and East Africa, have the highest rates of HIV infection among SW globally. Modeling suggests that due to the preventive effects of ART, scale up of ART access in Kenya for both female SW and their male clients to meet new WHO treatment guidelines of treatment initiation at CD4<500 could avert one-third of new HIV infections among SW and clients over the next decade.1

Since ART has been shown to impart significant reductions in onward transmission with the suppression of viral load, treatment for SW living with HIV is an important prevention priority as well as individual right and is essential to improved morbidity and mortality outcomes. Many SW community groups and advocates are rightfully cautious about HIV testing programs targeting SW—given the rights violations inherent in ongoing mandatory testing programs. Testing innovations, including self-testing, may help SW who wish to know their status free of coercion.33 Reducing discrimination in health care settings will also be a necessary part of successful treatment programs. Too many SW are treated as unwelcome, unworthy, and undeserving of the treatment they need.34,35 Violence and trauma have been shown to undermine treatment adherence, underscoring the need for trauma informed approaches for SW, where relevant.36–38

Molecular Epidemiology

Molecular epidemiology informs understanding of HIV transmission dynamics, spread of resistance, network and community level dynamics, and the role of acute and super-infection. Since SW share the potential risks of multiple partners, and for many, patterns of mobility and social mixing both for themselves and of their clients, they may face some distinct biological challenges to HIV prevention and treatment. SW have participated in many molecular epidemiologic investigations, including some early studies which demonstrated the utility of molecular approaches to understanding HIV outbreaks.39 Table 2 summarizes some of the recent work on molecular epidemiology among SW.

Table 2.

Recent studies on the molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 among sex workers

| Source | Population(s) | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Ssemwanga, et al, ARHR 201269 | 324 HIV + FSW Kampala, Uganda | Virology and partnership history. Women working in the same venues shared HIV variants; high rates of multiple HIV infections (dual and triple) |

| Carobene, et al, J Med Virol, 201470 | 273 HIV + Transgender SW, Argentina | Subtypes (BF, B, C, A) were similar to other risk groups. Many drug resistant variants, and 6.5% co-infection with HCV |

| Merati, et al, Sex Health, 201271 | 175 IDU, SW, MSM in Bali, Jakarta, Indonesia | IDU had 100% CRF-01A/E, sexual transmission (SW, MSM) had more mixed, non-A/E |

| Tran, et al, ARHR, 201240 | 284 women SW, Viet Nam | No NRTI or PI resistance mutations detected, although the rate of ART coverage had increased |

| Mehta, et al, ARHR, 201072 | Multiple sources, San Diego, USA, and Tijuana, Mexico | Molecular analysis showed distinct HIV outbreaks in these border cities |

| Pando, et al, ARHR 201121 | 12,192 persons: MSM, IDU, FSW, MSW, TGSW, FDU, Argentina | Transgender SW were the most HIV burdened group; but ARV resistance mutations were most common among women drug users |

| Land, et al, ARHR, 200873 | 240 persons, mixed risks, and Female SW, Nairobi, Kenya | HIV subtypes clustered by sex work status: less clade C, more recombinant subtypes in SW |

Encouragingly, recent studies have investigated, but not found, increases in ART resistance mutations in SW.40,41 Several groups have reported significant clustering of HIV subtypes by sex work status, clade differences from other high risk groups, linkage with general population samples, and high proportions of dual, multiple, and recombinant HIV infections.(Table 2) These findings are consistent with the multiple and repeated exposures. The molecular epidemiology of HIV among FSW is generally linked to heterosexual variants in the populations from which they come.(Table 2) Male and Transgender SW, in contrast, typically cluster with MSM populations, and less so with either FSW or other heterosexual networks.21,42,43

Female SW, and their distinctive risk exposures, have also been the subject of intensive research on HIV exposed seronegative individuals. Cohorts of FSW who have remained HIV uninfected despite very high levels of exposure to HIV have been studied in Kenya, Thailand, and Cote d’Ivoire since the 1990s.44–46 While a wide range of immunologic factors have been investigated to understand this phenomenon and its implications for HIV prevention, no single mucosal immunologic finding yet fully explains why subsets of women who sell sex may resist HIV acquisition.44,47,48

COSTING A NEW RESPONSE

Optimizing prevention for SWs and clients requires estimates of the costs and benefits of interventions within national and local contexts shaped by HIV epidemiology, by patterns and characteristics of sex work, and by economic, social, and policy environments. Unfortunately few cost-effectiveness studies focus on FSWs (and none on transgender SWs), and only limited data are available on intervention costs, infections averted, treatment costs saved, and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) averted. Mathematical models have begun to address some of these limitations by extrapolating the benefits and costs of interventions for FSWs, We reviewed the cost-effectiveness literature for individual-based and structural interventions for FSWs and clients. Modelling in this series of biomedical5 and structural1 interventions for FSWs also allows estimates of the thresholds for these interventions to be cost-saving or cost-effective and are also reported. Further details of these methods and results are presented in the accompanying online appendix 2.

One primary HIV prevention strategy, increasing condom use in sex work, has long been identified as an economical strategy.49 Mathematical models of the epidemic in South Africa suggest that increases in condom use during sex work since 1990 prevented 66% and 85% of new infections in clients and sex workers in 2010, respectively.5 In sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, peer/community counseling and condom distribution amongst FSWs was estimated to be cost-effective, at $86 per infection averted and $5 per DALY averted1, and was more cost-effective than school-based education, voluntary counseling and testing, prevention of mother-to-child transmission, and STI treatment.50 For the female condom, simulations indicate that distribution to rural Kenyan FSWs would be cost saving,51 but substitution of female condoms for less expensive male condoms that would otherwise have been used may limit financial benefits.52 Female condoms may be most appropriate when the use of male condoms is not a viable prevention strategy.53

Microbicides and oral PrEP are promising prevention strategies, but more data are needed on efficacy, acceptability, adherence, and risk compensation. Modelling by Bekker et al. reveals that even with modest uptake and efficacy and with decreased condom use, microbicide use by FSWs in South Africa could prevent 1,385 new infections among FSWs and clients over ten years,5 saving over $10m in HIV treatment costs (see Online Appendix 2). Based on estimated intervention costs in South Africa,54,55 microbicides are unlikely to come under the cost-saving threshold of $0.17 per sex act, but microbicides may meet the highly cost-effective threshold of $2.17 based on international standards.56

Use of PrEP by FSWs in South Africa would reduce incident infections among FSWs by 7.4% over ten years and prevent nearly 3,000 infections.5 With general population person-year costs estimated at $200 in South Africa,57 PrEP for FSWs would be cost saving. However, for both microbicides and PrEP, additional expenditures may be required to reach and engage FSWs and to facilitate adequate coverage and adherence. Drug costs will be a major determinant with Truvada costing as much as $10,000 per year in some countries.58 Additionally, local variation in HIV, condom use and patterns of sex work may dramatically affect the effectiveness of microbicides59 and oral PrEP.60

Periodic HIV testing and the offer of immediate treatment for FSWs is an especially promising intervention. Mathematical modelling reveals that over a 40-year period in Vietnam, an additional 19% investment in HIV testing and counseling and ART could prevent 31% of new infections at an estimated cost of $116/DALY.61 For FSWs in South Africa, a test-and-treat strategy over ten years could reduce infections among clients by 23%, prevent nearly 34,000 infections,5 and save $265m in treatment costs. However, investments of over $80m would likely be required to achieve these savings.

Individual-based interventions may require additional activities and resources when stigmatization affects prevention programs, when use of condoms as evidence of sex work affects condom carriage and usage, and when social exclusion affects access to care. Community-based, structural interventions, in contrast, change these contexts by creating safer work environments, reducing violence, and reducing police harassment.

Beattie et al. provide estimates of the effectiveness (but not the costs) of violence reduction interventions for FSWs,62 and modeling studies indicate that eliminating violence-attributable risk for HIV in various countries would substantially reduce HIV transmission.1,63 However, the investments required to achieve such benefits have not been established, and cost estimates are similarly needed for reducing police harassment and creating safer work environments.

Informing policy makers about the merits of sex work decriminalization requires better identification and quantification of the potential benefits and costs. Besides HIV prevention,1 other societal benefits may include increased access to police protection, improved occupational health and safety in sex work and the redirection of law enforcement and criminal justice expenditures towards health and social services.64 Even with rights-based law reform, advocacy and FSW-led interventions with police departments65 may be required to maximize the benefits in regards to reduced harassment and increase access to justice for FSWs.

Based on their modelling, Shannon et al.1 estimated that decriminalization of sex work would over ten years avert 72 infections among FSWs and clients in Vancouver, Canada, 233 infections in Bellary, India, and 1,155 infections in Mombasa, Kenya. The cost-saving and highly cost-effective thresholds for the decriminalization of sex work varies across these settings due to variations in the estimated number of infections averted, GDP, HIV treatment costs, and DALYs averted. For Vancouver, Bellary, and Mombasa, respectively, the cost-saving thresholds are estimated to be approximately $24m, $1.5m, and $12m (see Online Appendix 2).

Several cost-effectiveness studies demonstrate the value of community empowerment. In Ahmedabad, India, empowerment, outreach, peer education, condom distribution, and free STI clinics was cost saving, eliminating over 50% of incident infections among FSWs and their clients.66 Two community mobilization interventions in the Dominican Republic were cost-effective for reducing HIV at $523 and $1,356 per DALY averted.67 Modelled scale-up of empowerment-based approaches in Ukraine, Kenya, Brazil, and Thailand over a five-year period has demonstrated reductions in approximately 8–12% of new infections among SWs with benefits further enhanced by scale-up of ART.68 Kerrigan et al.9 estimated that the cost per DALY averted for these community empowerment-based interventions would vary from Ukraine ($87) and Kenya ($87) to Brazil ($1,448) and Thailand ($3,167).

These studies are elucidating how the prevention response may be improved, but much more research is required. We need to know how the cost-effectiveness of individual or combined FSW interventions is shaped by local and national contexts, and the costs and benefits of tailoring interventions to overcome the unique barriers to HIV risk reduction among FSWs and how to strengthen and leverage resilience.

CONCLUSIONS

The component of global HIV and AIDS related to SW has been understudied and under addressed for too long. It is clear that SW are in need of services globally, and that empowered and engaged individuals, collectives and communities want and will use those services if they are available in safety, dignity, and freedom from harassment. Recognizing the diversity of SW and their environments and appropriately tailoring promising HIV interventions to the specific contexts is a public health priority. Many HIV interventions which meet efficacy and/or effectiveness criteria would also be cost saving. In the current policy and funding climate where some donors seek to transition to country ownership of HIV efforts, HIV programs for sex workers may be challenged. All engaged in the HIV response must work to ensure that effective programs for sex workers are supported and sustained in these transitions.

Punitive approaches to sex work have hindered our responses and aided and abetted the HIV virus. They remain barriers to pragmatic and public health oriented approaches which can reduce transmission, save lives, and reduce violence and rights abuses against the women, men, and transgender persons who sell sex. The rich evidence base for community-based interventions how us that when SW lead in interventions, real and measureable improvements in health and rights can be achieved. The coming together of community engagement and new biomedical tools for HIV prevention and treatment offer the promise of dramatic reductions in HIV risks and burdens for sex workers in the future, and could reduce treatment costs and save lives. If these advances can be made available in policy contexts where carrying condoms is seen as a positive, where police protect SW from violence rather than perpetrate it, and where outcomes of policies are measured in reduced HIV infections, not increases in arrests, this component of the global HIV response could be markedly more effective.

Table 3.

Calls for action for stakeholders in the HIV response for sex workers.

| Stakeholders | Actions | Evidence/Rationale |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Community | Engage in sex worker community empowerment, commit to activism | Kerrigan et al, Lancet 2014,8 Community engagement is cost-effective and reduces HIV risks |

| Advocate for universal access to services, including HIV services provided with dignity, safety, and confidentiality | ||

| Monitor the work of governments, donors and multilaterals and hold them accountable for adequate programming and policy to address HIV among sex workers | ||

|

| ||

| Governments | Decriminalize sex work | Shannon, et al, Lancet 2014,1 decriminalization can improve the risk environment |

| End impunity for crimes and abuses committed against sex workers | Decker, et al, Lancet 20143 | |

| Advance evidence-based policies and practices in partnership with sex worker led organizations | ||

| End discriminatory laws, policies and practices against female, male and transgender sex workers | Decker et al, Lancet 20143 Baral et al, Lancet 20146 Poteat et al, Lancet 20147 | |

| Include sex workers in epidemiological surveillance and make results publicly available | ||

| Include civil society, including sex worker led organizations, in national policy planning | ||

| Recognize sex work as work and develop occupational health and safety standards, mechanisms to redress violence against sex workers and other labor and human rights violations | ||

|

| ||

| Donors | Address the current under-funding of the responses to HIV among sex workers. | |

| Increase support for the research agenda for combination HIV prevention and care services for sex workers | Novel and combined enhanced prevention and treatment programs have not been investigated among SW | |

| Support sex worker-led organizations at global, regional and country levels | Community organizations need funding in order to participate in the HIV response. | |

| Empowerment models require funding of community-led organizations rather than to organizations working with communities.74,75 | ||

| Invest in strategic information on HIV and sex work | Reliable data on HIV and sex work is needed including access to ART and ART coverage, condoms and lubricants, comprehensive SRH services; migration and mobility; trafficking in persons meeting the Palermo Protocol; gender based violence; affirmative action addressing human rights violations towards sex workers | |

| Harmonize donor responses | Competing interventions, including those driven by ideology and not science are limiting the scale and efficacy of the HIV response among sex workers. Kerrigan et al., World Bank 2012.8,9 | |

|

| ||

| Implementers & Providers | Tailor care and support programmes for sex workers living with HIV | Sex workers commonly live and work away from home communities. National and local support for the wider population living with HIV is unavailable to sex workers |

| Scale up comprehensive HIV/STI/SRH programmes for sex workers that are non-stigmatising and meet quality standards | Sex workers face inadequate access to ART, condoms and lubricants, safe abortions and post-abortion care, STI management, contraception services, vertical transmission programmes, maternal health services and drug treatment services | |

| Act to reduce stigma and discrimination in health care settings for sex workers | ||

| Refrain from participation in health programmes that are not evidence based | ||

| Ensure training in culturally competent care for all personnel in clinical settings, including non-clinical staff (security, intake) who may interact with sex workers | ||

|

| ||

| Researchers | Partner with sex worker communities and organizations to focus research efforts on questions of relevance to sex workers | Partnerships between researchers and sex worker communities have led to some of the most robust research findings on HIV prevention. |

| Investigate novel options for HIV prevention, treatment and care for sex workers of all genders, including in challenging policy environments | ||

| Take advantage of natural experiments to evaluate the impact of various sex work regulations on HIV incidence, prevention, care and treatment | ||

| Dispel myths about sex workers that undermine access to HIV prevention, care and treatment | Research can be a powerful tool to dispel myths about sex workers (Shannon et al, Lancet, 2014)1 | |

| Expand implementation science and operations research to develop and refine HIV services for sex workers | ||

| Expand research on sex worker relevant issues in understudied regions, including Africa, the Middle East, Eastern Europe and Central Asia | Very little prevention or treatment research has been conducted in some critical areas where HIV epidemics continue to expand | |

| Expand research on HIV prevention and treatment for male and transgender sex workers, particularly in regions where there are currently little or no data | No research has been done for or with male and transgender sex workers in the majority of countries worldwide. HIV data on Transgender women in general are available for only 15 countries in 2013.(Baral, et al, LID, 2013.)76 | |

Text Box 1. Christine’s story, Myanmar.

I started selling sex when I was 18. When I was 15 or 16, I started taking [a form of] cough syrup as a drug. My friends were doing drugs, and then I got a boyfriend who also used drugs so we started doing it together. Then we broke up and I started trading sex for drugs.

In 2008, Cyclone Nargis hit my country. During the cyclone, my father passed away. After his death, I had to look after my family. Before the cyclone, I was not forced to sell sex; I could choose when and with whom, and I could say no. But after the cyclone, I had to go with any client that came. Some clients were good and some were bad. But I wanted to give my little sister and brothers an education, and my grandmother needed an eye operation.

To deal with the stress, I started taking more cough syrup. At first I didn’t take a lot, but then I started using it to get high and ease the pain. The drugs made me feel inner peace and also allowed me to do more work since I didn’t need to sleep. It was a circle of doing drugs, and needing money for drugs and my siblings’ education.

I had some health problems in the beginning, like excessive discharge, pain and bruising. My fellow sex workers and I helped each other to heal our health issues. You need to have a group where you can discuss issues and solve problems together; you can discuss your feelings like if you are happy or sad. I had an implant for birth control in case a condom broke, but I also used condoms and every three months went for a HIV test.

I never wanted problems with the police, so whenever they wanted to have sex, I gave it to them for free. They didn’t care if I was tired or didn’t want to – they just told me they want it. Also, the police made us pay for their food in tea houses. If I went to do sex work in a different area of my city, I had to make a deal with the police chief of that area. Sometimes I had to give them money for alcohol.

Through having saved money, I finally managed to support education for my two younger brothers and my sister, and I was able to pay for my grandmother’s eye operation. I also got a job in an international non-governmental organization, and they helped me to stop my [drug] addiction through keeping me busy with work but also providing me information about drug use. Having the job with the NGO made my grandmother so proud of me – she cried when I told her the news.

I still do sex work sometimes when I travel because my job doesn’t pay me enough to support my family. My salary is only 100 dollars a month. But I feel proud at what I’ve achieved.

I want to keep working on human rights issues, and also support other young people like me.

Text box 2. Search Strategy for Global Burden of HIV among Female Sex Workers.

We updated the 2012 estimates by Baral and colleagues2 to identify new publications since the last search and to conduct a global analysis, now including high-income countries. We searched PubMed and EMBASE for studies published between January 1, 2007, and June 20, 2013. Articles and citations were downloaded, organized, and reviewed using the QUOSA information management software package (version 8.05) and EndNote (version X4). The search included MeSH terms for HIV or AIDS, and terms associated with sex work (prostitute [MeSH] OR “sex work” OR “sex work*” OR “female sex worker” OR “commercial sex worker” AND HIV [MeSH] OR AIDS [MeSH] OR “HIV” OR “AIDS”). Other data sources included UNAID and national surveillance system data reports, including demographic health surveys, and integrated biobehavioral surveillance studies conducted by large international non-governmental organizations.

Studies and reports from low, middle, and high-income countries were included in the analysis. We included studies with samples sizes greater than 50 female sex workers and of any design that measured the prevalence or incidence of HIV among female sex workers. Studies were accepted if clear descriptions of sampling, HIV testing methods (i.e. laboratory derived HIV status with biological samples from blood, urine, or oral specimens) and analytic methods were included. Studies with self-reported HIV status were excluded. Estimated derived from respondent-driven sampling that did not provide sample sizes and unweighted estimates were excluded from analysis. Studies in which female sex workers were not the main focus of the study were included only if results were disaggregated to provide results specific to female sex workers. Additionally, studies that required additional criteria for inclusion, such as injection drug use or current incarceration were excluded.

Text Box 3. The Global Commission on HIV and the Law – making the law work for HIV and health.

In 2011, the Global Commission on HIV and the Law examined the relationship between law and public health in the context of HIV. The 14 member independent commission, chaired by Fernando Henrique Cardoso (former President of Brazil), assessed research and submissions from more than 1000 authors covering 140 countries, as well as engaging parliamentarians, ministries of justice and health, judiciary, lawyers, police and civil society in frank and constructive policy dialogue.

The Commission concluded that laws criminalizing consensual adult sex, as well as a range of other laws and legal practices, are undermining effective HIV programming with and for sex workers. The Commission found that:

Laws against consensual adult sex work impede HIV prevention, allow for police harassment and violence, and weaken sex workers ability to negotiate safe sex. These laws deter sex workers from accessing HIV and other health services and increase HIV vulnerability.

Criminal laws conflate trafficking with consensual adult sex work, and the broad deployment of anti-trafficking laws against sex work results in denial of human rights of people in sex work. The harms from this conflation have increased over the past decade as much HIV funding has been predicated on the acceptance of the conflation of trafficking with consensual adult sex work.

Criminalizing the clients of sex workers impacts negatively on sex workers and hinders effective HIV responses. This approach shifts sex work into underground settings with less security, more violence and increased vulnerability to HIV, and worsens the lives of sex workers.

Rights-based approaches that empower sex workers and engage law enforcement officials are critical to effective HIV responses. When the rights of sex workers are recognized, they have collectivized to protect their health, bodily integrity and control HIV.

Progress is being made: SW are increasingly organizing and demanding recognition that they not lose their rights when involved in sex work. Some communities have had long experience with rights-based approaches to sex work and data shows that HIV and other health outcomes have improved. Some countries have moved away from the “rehabilitation” center model and other punitive approaches, and recent court decisions have begun to disentangle the conflation of sex work with human trafficking, including by striking down punitive conditions in development assistance.

The Commission concluded that countries should reform their approach towards sex work so that consenting adults involved in sex work are not punished but are ensured safe working conditions, and that SW and clients have access to HIV and health services. Countries must also take all measures to stop police harassment and violence against sex workers, including stopping mandatory HIV and STI testing. Countries must also ensure that the enforcement of anti-human trafficking laws is carefully targeted to punish those who use force, dishonesty or coercion to procure people into sex work. Anti- trafficking laws must be used to prohibit sexual exploitation of adults and children and they must not be used against adults involved in consensual sex work.

Reforming legal environments related to sex work is not without political challenges but it is the right thing to do. It is essential to curbing the HIV epidemic and to ensuring the realization of human rights.

Text Box 4. The Melbourne 2014 Declaration.

Nobody Left Behind

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Article 1, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948.

We gather in Melbourne, the traditional meeting place of the Wurundjeri, Boonerwrung, Taungurong, Djajawurrung and the Wathaurung people, the original and enduring custodians of the lands that make up the Kulin Nation, to assess progress on the global HIV response and its future direction, at the 20th International AIDS Conference, AIDS 2014.

We, the signatories and endorsers of this Declaration, affirm that non-discrimination is fundamental to an evidence-based, rights-based and gender transformative response to HIV and effective public health programmes.

To defeat HIV and achieve universal access to HIV prevention, treatment, care and support – nobody should be criminalized or discriminated against because of their gender, age, race, ethnicity, disability, religious or spiritual beliefs, country of origin, national status, sexual orientation, gender identity, status as a sex worker, prisoner or detainee, because they use or have used illicit drugs or because they are living with HIV.

We affirm that all women, men, transgender and intersex adults and children are entitled to equal rights and to equal access to HIV prevention, care and treatment information and services. The promotion of gender equity is essential to HIV responses that truly meet the needs of those most affected. Additionally, people who sell or who have sold sex, and people who use, or who have used illicit drugs are entitled to the same rights as everyone else, including non-discrimination and confidentiality in access to HIV care and treatment services.

We express our shared and profound concern at the continued enforcement of discriminatory, stigmatizing, criminalizing and harmful laws which lead to policies and practices that increase vulnerability to HIV. These laws, policies, and practices incite extreme violence towards marginalized populations, reinforce stigma and undermine HIV programmes, and as such are significant steps backward for social justice, equality, human rights and access to health care for both people living with HIV and those people most at risk of acquiring the virus.

In over 80 countries, there are unacceptable laws that criminalize people on the basis of sexual orientation. All people, including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people are entitled to the same rights as everyone else. All people are born free and equal and are equal members of the human family.

Health providers who discriminate against people living with HIV or groups at risk of HIV infection or other health threats, violate their ethical obligations to care for and treat people impartially.

We therefore call for the immediate and unified opposition to these discriminatory and stigmatizing practices and urge all parties to take a more equitable and effective approach through the following actions:

Governments must repeal repressive laws and end policies that reinforce discriminatory and stigmatizing practices that increase the vulnerability to HIV, while also passing laws that actively promote equality.

Decision makers must not use international health meetings or conferences as a platform to promote discriminatory laws and policies that undermine health and wellbeing.

The exclusion of organisations that promote intolerance and discrimination including sexism, homophobia, and transphobia against individuals or groups, from donor funding for HIV programmes.

All healthcare providers must demonstrate the implementation of non-discriminatory policies as a prerequisite for future HIV programme funding.

Restrictions on funding, such as the anti-prostitution pledge and the ban on purchasing needles and syringes, must be removed as they actively impede the struggle to combat HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and hepatitis C among sex workers and people who inject drugs.

Advocacy by all signatories to this Declaration for the principles of inclusion, non-criminalization, non-discrimination, and tolerance.

In conclusion we reaffirm our unwavering commitment to fairness, to universal access to health care and treatment services, and to support the inherent dignity and rights of all human beings. All people are entitled to the rights and protections afforded by international human rights frameworks.

An end to AIDS is only possible if we overcome the barriers of criminalization, stigma and discrimination that remain key drivers of the epidemic.

KEY MESSAGES.

HIV epidemics among female sex workers generally reflect the HIV burden in heterosexual adults in their surrounding communities, but with significantly higher HIV incidence and prevalence. The most burdened sex workers are African women—and all countries with over 50% HIV prevalence in sex workers are in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Male and Transgender sex workers have very high HIV risks and burdens, reflecting the high HIV incidence seen among gay, bisexual, and other MSM at risk worldwide.

Structural determinants, including laws, policies, rights contexts, community organization, and the physical and economic features of sex work play critical roles in generating or mitigating risks for HIV infection among sex workers. Modeling suggests that decriminalization of sex work could avert 33–46% of new HIV infections among sex workers and clients over a decade, through its iterative effects on violence, policing, safer work environment, and HIV transmission.

Human rights violations against sex workers increase HIV vulnerability and undermine effective prevention. Many rights violations, including physical and sexual violence by police and other state actors, are the result of climates of impunity which must change.

Decriminalization, expanded access to antiviral treatment for sex workers living with HIV, and community empowerment and engagement could have synergistic impacts on reducing HIV infections among sex workers.

Community empowerment-based HIV prevention has been shown to significantly reduce HIV risks, gonorrhea, and chlamydia infections in female sex workers, and to increase condom use with clients. There is a need for social and political change related to the recognition of sex work as work and scale-up of empowerment-based approaches to HIV prevention for SW.

Peer/community counseling and condom distribution among female sex workers has been shown to be cost-effective in SE Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, and was more cost-effective than school-based education, voluntary counseling and testing, prevention of mother-to-child transmission, and STI treatment.

Combination HIV prevention programs which address biological drivers of HIV infection, including tailored use of anti-retroviral agents in PEP, PrEP, and rectal microbicides, will likely be needed to prevent HIV among male and transgender sex workers. Ensuring high coverage of HIV testing, and ART treatment access will be key to health outcomes and to reducing HIV transmission. These approaches should be carefully added to tailored prevention packages that recognize and respect communities’ human rights in program design and implementation. Equitable funding for HIV programming can support these efforts.

Research is urgently needed on the epidemiology of HIV among sex workers and on novel effective interventions and combination interventions. The global lack of data on HIV among transgender women and male sex workers calls for more and better research among these populations to identify needs and inform prevention efforts and treatment access.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the contribution and thank the following individuals: Aleksandra Mihailovic and Hae-Young Kim, research assistants at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Dept. of Epidemiology, for their contributions to the search and data abstraction for the analysis of the global prevalence of HIV among sex workers; Mandeep Dhaliwal of UNDP for the text box on the Global Commission on HIV and the Law; The Conference Coordinating Committee of the 20th International AIDS Conference for the Melbourne 2014 Declaration.

This paper and The Lancet Series on HIV and Sex Work was supported by grants to the Center for Public Health and Human Rights at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health from The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; The United Nations Population Fund; the Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research, an NIH funded program (1P30AI094189), which is supported by the following NIH Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH,NIA, FIC, and OAR; and by The Johns Hopkins HIV Epidemiology and Prevention Sciences Training Program (1T32AI102623-01AI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

All costs herein expressed in 2012 US$

To sign on to the Melbourne 2014 Declaration visit: www.aids2014.org/declaration.aspx

References

- 1.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, et al. The global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: the influence of structural determinants. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60931-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet InfectDis. 2012;12(7):538–49. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Decker MR, Crago AL, Chu S, Sherman SG, Dhaliwal M, Beyrer C. Human rights and HIV among sex workers. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60800-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Havlir D, Beyrer C. The beginning of the end of AIDS? NEnglJMed. 2012;367(8):685–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1207138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bekker LG, Johnson L, Overs S, et al. Combination HIV prevention for female sex workers: what is the evidence? Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60974-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baral SD, Friedman MR, Caceres C, et al. Male sex workers: biological, behavioral, and structural risks for HIV acquisition and transmission. Lancet. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Radix A, et al. A comprehensive review of HIV risk and prevention interventions among transgender women sex workers. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60833-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerrigan DL, Kennedy CE, Thomas RM, et al. Community empowerment-based HIV prevention among sex workers: effectiveness, challenges, and considerations for implementation and scale-up. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60973-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerrigan D. The Global HIV Epidemics among Sex Workers. Washington, D.C.: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jana S, Rojanapithayakorn W, Steen R. Harm reduction for sex workers. Lancet. 2006;367(9513):814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steen R, Zhao P, Wi TE, Punchihewa N, Abeyewickreme I, Lo YR. Halting and reversing HIV epidemics in Asia by interrupting transmission in sex work: experience and outcomes from ten countries. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2013;11(10):999–1015. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2013.824717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mills E, Rachlis B, Wu P, Wong E, Wilson K, Singh S. Media reporting of tenofovir trials in Cambodia and Cameroon. BMCIntHealth HumRights. 2005;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masenior NF, Beyrer C. The US anti-prostitution pledge: First Amendment challenges and public health priorities. PLoS Med. 2007;4(7):e207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ditmore MH, Allman D. An analysis of the implementation of PEPFAR’s anti-prostitution pledge and its implications for successful HIV prevention among organizations working with sex workers. JIntAIDS Soc. 2013;16:17354. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.17354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Committee on the Outcome and Impact Evaluation of Global HIV/AIDS Programs Implemented Under the Lantos-Hyde Act of 2008; Board on Global Health; Board on Children Y, and Families; Institute of Medicine. Evaluation of PEPFAR. The National Academies Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prüss-Ustün A, Wolf J, Driscoll T, Degenhardt L, Neira M, Calleja JM. HIV due to female sex work: regional and global estimates. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelmon L, (Kenya) NACC . Kenya HIV Prevention Response and Modes of Transmission Analysis. National AIDS Control Council; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wabwire-Mangen F, Commission UA, HIV/AIDS. JUNPo . Uganda HIV Modes of Transmission and Prevention Response Analysis: Final Report, March 2009. Uganda National AIDS Commission; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.UNAIDS. New HIV Infections by mode of transmission in West Africa: A Multi-Country Analysis Dakar. UNAIDS, World Bank; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steen R, Hontelez JA, Veraart A, White RG, de Vlas SJ. Looking upstream to prevent HIV transmission: can interventions with sex workers alter the course of HIV epidemics in Africa as they did in Asia? AIDS (London, England) 2014;28(6):891–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pando MA, Gomez-Carrillo M, Vignoles M, et al. Incidence of HIV type 1 infection, antiretroviral drug resistance, and molecular characterization in newly diagnosed individuals in Argentina: A Global Fund Project. AIDS ResHumRetroviruses. 2011;27(1):17–23. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UNAIDS. Global report UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic: 2013. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christenson K. Four game-changing HIV/AIDS treatments. oneorg. 2011 11/16/2011. http://www.one.org/us/2011/11/16/four-game-changing-hivaids-treatments/ (accessed 2/16/2014)

- 24.Mas de Xaxas M, OΓÇÖReilly K, Evans C, Higgins D, Gillies P, Jana S. Meeting community needs for HIV prevention and more: Intersectoral action for health in the Sonagachi red-light area of Kolkata. Geneva: WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh JP, Hart SA. Sex Workers and Cultural Policy: Mapping the Issues and Actors in Thailand. Review of Policy Research. 2007;24(2):155–73. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerrigan DL, Fonner VA, Stromdahl S, Kennedy CE. Community empowerment among female sex workers is an effective HIV prevention intervention: a systematic review of the peer-reviewed evidence from low- and middle-income countries. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):1926–40. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medley A, Kennedy C, O’Reilly K, Sweat M. Effectiveness of peer education interventions for HIV prevention in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS EducPrev. 2009;21(3):181–206. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baeten JM, Haberer JE, Liu AY, Sista N. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: where have we been and where are we going? JAcquirImmune DeficSyndr. 2013;63(Suppl 2):S122–S9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182986f69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNairy ML, Howard AA, El Sadr WM. Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of HIV and tuberculosis: a promising intervention but not a panacea. JAcquirImmune DeficSyndr. 2013;63(Suppl 2):S200–S7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182986fc6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):341–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanser F, Barnighausen T, Grapsa E, Zaidi J, Newell ML. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Science. 2013;339(6122):966–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1228160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. NEnglJMed. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pant PN, Sharma J, Shivkumar S, et al. Supervised and unsupervised self-testing for HIV in high- and low-risk populations: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2013;10(4):e1001414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghoshal N. “Treat us like human beings” : discrimination against sex workers, sexual and gender minorities, and people who use drugs in Tanzania2013. 2013 http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/tanzania0613webwcover_0_0.pdf (accessed.

- 35.Scorgie F, Nakato D, Harper E, et al. ‘We are despised in the hospitals’: sex workers’ experiences of accessing health care in four African countries. CultHealth Sex. 2013;15(4):450–65. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.763187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mugavero M, Ostermann J, Whetten K, et al. Barriers to antiretroviral adherence: the importance of depression, abuse, and other traumatic events. AIDS PatientCare STDS. 2006;20(6):418–28. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Reif S, et al. Overload: impact of incident stressful events on antiretroviral medication adherence and virologic failure in a longitudinal, multisite human immunodeficiency virus cohort study. PsychosomMed. 2009;71(9):920–6. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bfe8d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schafer KR, Brant J, Gupta S, et al. Intimate partner violence: a predictor of worse HIV outcomes and engagement in care. AIDS PatientCare STDS. 2012;26(6):356–65. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beyrer C, Artenstein A, Kunawararak P, et al. The molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 among male sex workers in northern Thailand. JAcquirImmune DeficSyndrHumRetrovirol. 1997;15(4):304–7. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199708010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tran VT, Ishizaki A, Nguyen CH, et al. No increase of drug-resistant HIV type 1 prevalence among drug-naive individuals in Northern Vietnam. AIDS ResHumRetroviruses. 2012;28(10):1349–51. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chamberland A, Diabate S, Sylla M, et al. Transmission of HIV-1 drug resistance in Benin could jeopardise future treatment options. Sex TransmInfect. 2012;88(3):179–83. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aguayo N, Laguna-Torres VA, Villafane M, et al. Epidemiological and molecular characteristics of HIV-1 infection among female commercial sex workers, men who have sex with men and people living with AIDS in Paraguay. RevSocBrasMedTrop. 2008;41(3):225–31. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822008000300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jung M, Leye N, Vidal N, et al. The origin and evolutionary history of HIV-1 subtype C in Senegal. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yao XD, Omange RW, Henrick BM, et al. Acting locally: innate mucosal immunity in resistance to HIV-1 infection in Kenyan commercial sex workers. MucosalImmunol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jennes W, Evertse D, Borget MY, et al. Suppressed cellular alloimmune responses in HIV-exposed seronegative female sex workers. ClinExpImmunol. 2006;143(3):435–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beyrer C, Artenstein AW, Rugpao S, et al. Epidemiologic and biologic characterization of a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 highly exposed, persistently seronegative female sex workers in northern Thailand. Chiang Mai HEPS Working Group. JInfectDis. 1999;179(1):59–67. doi: 10.1086/314556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chege D, Chai Y, Huibner S, et al. Blunted IL17/IL22 and pro-inflammatory cytokine responses in the genital tract and blood of HIV-exposed, seronegative female sex workers in Kenya. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lajoie J, Juno J, Burgener A, et al. A distinct cytokine and chemokine profile at the genital mucosa is associated with HIV-1 protection among HIV-exposed seronegative commercial sex workers. MucosalImmunol. 2012;5(3):277–87. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rojanapithayakorn W. The 100% condom use programme in Asia. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14(28):41–52. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)28270-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hogan DR, Baltussen R, Hayashi C, Lauer JA, Salomon JA. Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies to combat HIV/AIDS in developing countries. BMJ. 2005;331(7530):1431–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38643.368692.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marseille E, Kahn JG, Billinghurst K, Saba J. Cost-effectiveness of the female condom in preventing HIV and STDs in commercial sex workers in rural South Africa. SocSciMed. 2001;52(1):135–48. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomsen SC, Ombidi W, Toroitich-Ruto C, et al. A prospective study assessing the effects of introducing the female condom in a sex worker population in Mombasa, Kenya. Sex TransmInfect. 2006;82(5):397–402. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.019992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hernan L, Kahn JG, Marseille E, Pham HV. Smarter Programming of the Female Condom: Increasing Its Impact on HIV Prevention in the Developing World. Boston. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walensky RP, Park JE, Wood R, et al. The cost-effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection in South African women. ClinInfectDis. 2012;54(10):1504–13. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams BG, Abdool Karim SS, Karim QA, Gouws E. Epidemiological impact of tenofovir gel on the HIV epidemic in South Africa. JAcquirImmune DeficSyndr. 2011;58(2):207–10. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182253c19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.World Health Organization, Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Sachs J. Macroeconomics and health investing in health for economic development : report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health2001. 2001 (accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hallett TB, Baeten JM, Heffron R, et al. Optimal uses of antiretrovirals for prevention in HIV-1 serodiscordant heterosexual couples in South Africa: a modelling study. PLoS Med. 2011;8(11):e1001123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hellinger FJ. Assessing the cost effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in the US. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(12):1091–104. doi: 10.1007/s40273-013-0111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vickerman P, Watts C, Delany S, Alary M, Rees H, Heise L. The importance of context: model projections on how microbicide impact could be affected by the underlying epidemiologic and behavioral situation in 2 African settings. Sex TransmDis. 2006;33(6):397–405. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000218974.77208.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vissers DC, Voeten HA, Nagelkerke NJ, Habbema JD, de Vlas SJ. The impact of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) on HIV epidemics in Africa and India: a simulation study. PLoS One. 2008;3(5):e2077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kato M, Granich R, Bui DD, et al. The potential impact of expanding antiretroviral therapy and combination prevention in Vietnam: towards elimination of HIV transmission. JAcquirImmune DeficSyndr. 2013;63(5):e142–e9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829b535b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beattie TS, Bhattacharjee P, Ramesh BM, et al. Violence against female sex workers in Karnataka state, south India: impact on health, and reductions in violence following an intervention program. BMCPublic Health. 2010;10:476. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Decker MR, Wirtz AL, Pretorius C, et al. Estimating the impact of reducing violence against female sex workers on HIV epidemics in Kenya and Ukraine: a policy modeling exercise. AmJReprod Immunol. 2013;69(Suppl 1):122–32. doi: 10.1111/aji.12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abel G, Fitzgerald L, Brunton C. Report to the Prostitution Law Review Committee. Christchurch: University of Otago; 2007. The impact of the Prostitution Reform Act on the health and safety practices of sex workers. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Biradavolu MR, Burris S, George A, Jena A, Blankenship KM. Can sex workers regulate police? Learning from an HIV prevention project for sex workers in southern India. SocSciMed. 2009;68(8):1541–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fung IC, Guinness L, Vickerman P, et al. Modelling the impact and cost-effectiveness of the HIV intervention programme amongst commercial sex workers in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. BMCPublic Health. 2007;7:195. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sweat M, Kerrigan D, Moreno L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of environmental-structural communication interventions for HIV prevention in the female sex industry in the Dominican Republic. JHealth Commun. 2006;11(Suppl 2):123–42. doi: 10.1080/10810730600974829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wirtz AL, Pretorius C, Beyrer C, et al. Epidemic impacts of a community empowerment intervention for HIV prevention among female sex workers in generalized and concentrated epidemics. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ssemwanga D, Kapaata A, Lyagoba F, et al. Low drug resistance levels among drug-naive individuals with recent HIV type 1 infection in a rural clinical cohort in southwestern Uganda. AIDS ResHumRetroviruses. 2012;28(12):1784–7. doi: 10.1089/AID.2012.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carobene M, Bolcic F, Farias MS, Quarleri J, Avila MM. HIV, HBV, and HCV molecular epidemiology among trans (transvestites, transsexuals, and transgender) sex workers in Argentina. JMedVirol. 2014;86(1):64–70. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Merati TP, Ryan CE, Spelmen T, et al. CRF01_AE dominates the HIV-1 epidemic in Indonesia. Sex Health. 2012;9(5):414–21. doi: 10.1071/SH11121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mehta SR, Delport W, Brouwer KC, et al. The relatedness of HIV epidemics in the United States-Mexico border region. AIDS ResHumRetroviruses. 2010;26(12):1273–7. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]