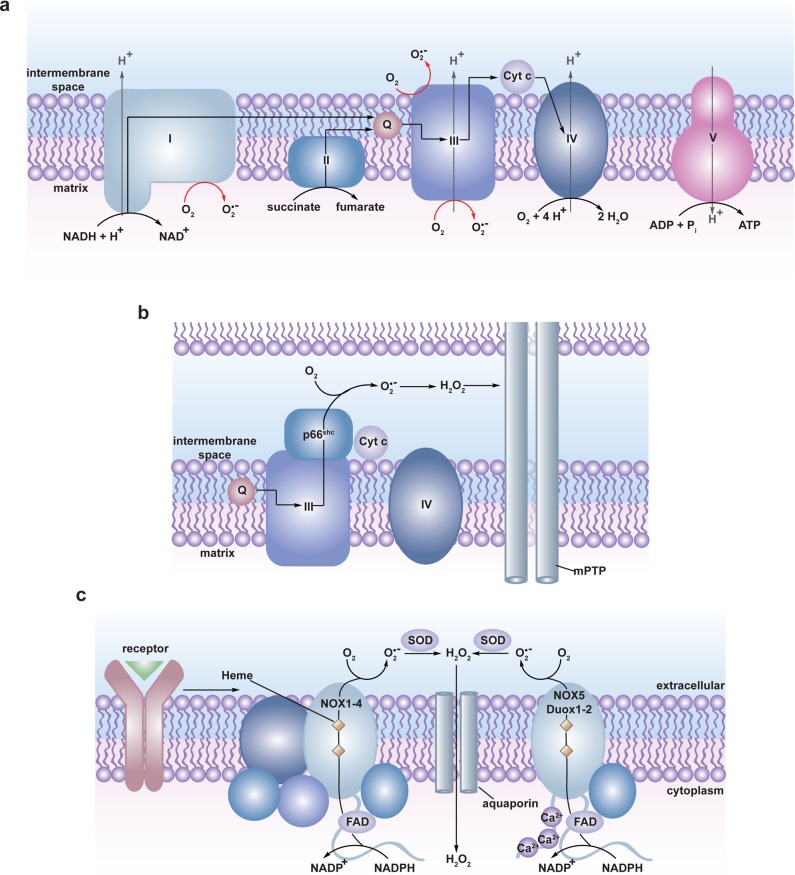

Figure 1.

Biological sources of reactive oxygen species (ROS). (a) The mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC). Four protein complexes (I–IV) funnel electrons (black arrows) from NADH and succinate in the matrix to ultimately reduce molecular oxygen to water and establish a proton gradient (gray arrows) that is harnessed by complex V to generate ATP. Electrons can leak prematurely from the ETC at complexes I and III (red arrows) to generate superoxide (O2•–) in either the matrix or intermembrane space. (b) p66 (Shc) facilitates pro-apoptotic O2•– or H2O2 production in the mitochondria. In response to UV irradiation or growth factor deprivation, p66 (Shc) localizes to the mitochondria where it interacts with complex III to divert electrons from cytochrome c directly to molecular oxygen to generate O2•– or H2O2. This H2O2 can translocate to the cytoplasm (not shown) where it can influence signaling, and can regulate opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), which initiates mitochondrial swelling and apoptosis. (c) NOX enzyme complexes assemble at distinct regions of the plasma membrane or intracellular membranes to regulate localized ROS production in response to diverse signals. Receptor stimulation initiates the recruitment of specific coactivating proteins or calcium to one of seven NOX catalytic cores. Once activated, NOX enzymes funnel electrons from NADPH in the cytoplasm through FAD and heme cofactors across the membrane to generate O2•– (NOX1-2) or H2O2 (Duox1-2) on the extracellular/lumenal face. O2•– is dismutated to H2O2 and oxygen either spontaneously or as enhanced by SOD, which can translocate across the membrane by diffusion or, more likely, through aquaporin channels to regulate protein activity and signaling in the cytoplasm.