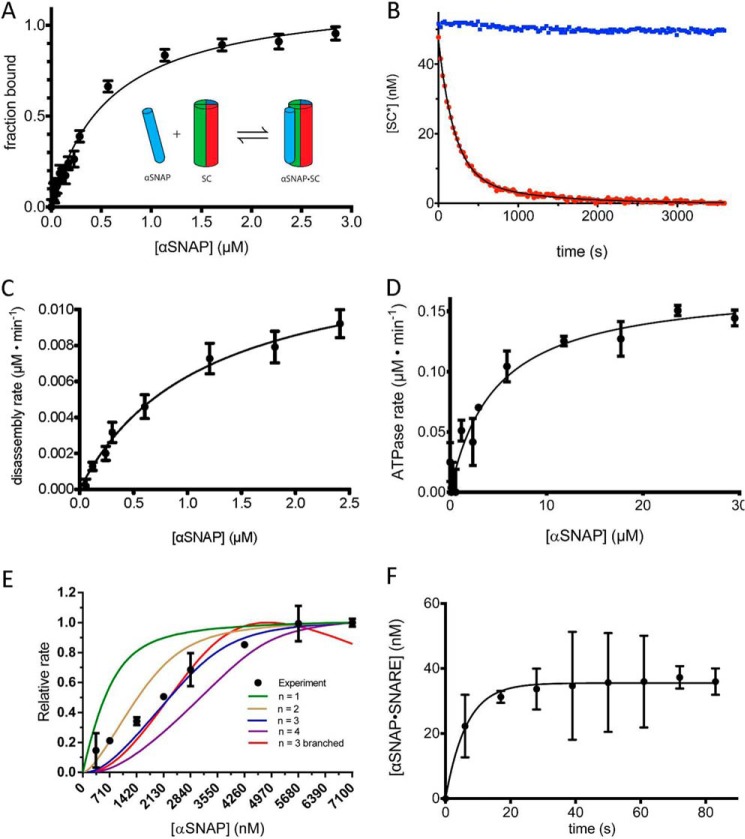

FIGURE 2.

The role of αSNAP in binding and disassembling the SNARE complex. A, SC containing labeled VAMP2-A488 (50 nm) was combined with increasing concentrations of αSNAP (0–3 μm), and the change in fluorescence anisotropy was measured. The data are shown fit to a single-site binding curve giving KdαSNAP·SNAREd = 450 ± 52 nm. The inset schematic shows a single αSNAP interaction with the SC. B, representative disassembly assay. Alexa Fluor 488-labeled SC (SC*) (50 nm) was combined with excess αSNAP (4 μm) and disassembled by NSF (2 nm) in the presence of ATP (1 mm) and Mg2+ (5 mm) (red). A control experiment was performed in the absence of Mg2+ (blue). C, initial rates of SC disassembly in steady-state conditions were measured with increasing concentrations of αSNAP (0–2500 nm). The data are fit to the equation, v = Vmax/(1 + Km/αSNAP) to give the maximal rate kcat and KmαSNAP for SC (solid black line) (Table 2). D, the ATPase activity of NSF as a function of αSNAP concentration. The data are fit to the equation, ν = Vmax/(1 + (Km/[αSNAP])) (solid black line) to give the KmαSNAP for NSF ATPase activity. E, SC disassembly rates (y axis) were measured with SC and NSF at high, fixed concentrations (1 μm each) with a range of αSNAP concentrations (0.4–7.1 μm). The lines correspond to models with different αSNAP stoichiometry, as indicated in the key. Descriptions of the models can be found under “Experimental Procedures.” F, association of αSNAP (2 μm) with SC (50 nm) as measured by fluorescence anisotropy. A 6-s instrument dead time was accounted for by shifting the data points 6 s in the direction of the positive x axis. Error bars, S.E.