Abstract

Background

Hilar cholangiocarcinoma is the most common malignant tumor affecting the extrahepatic bile duct. Surgical treatment offers the only possibility of cure, and it requires removal of all tumoral tissues with adequate resection margins. The aims of this review are to summarize the findings and to discuss the controversies on the extent of surgical resection aiming at cure for hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Methods

The English medical literatures on hilar cholangiocarcinoma were studied to review on the relevance of adequate resection margins, routine caudate lobe resection, extent of liver resection, and combined vascular resection on perioperative and long-term survival outcomes of patients with resectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Results

Complete resection of tumor represents the most important prognostic factor of long-term survival for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. The primary aim of surgery is to achieve R0 resection. When R1 resection is shown intraoperatively, further resection is recommended. Combined hepatic resection is now generally accepted as a standard procedure even for Bismuth type I/II tumors. Routine caudate lobe resection is also advocated for cure. The extent of hepatic resection remains controversial. Most surgeons recommend major hepatic resection. However, minor hepatic resection has also been advocated in most patients. The decision to carry out right- or left-sided hepatectomy is made according to the predominant site of the lesion. Portal vein resection should be considered when its involvement by tumor is suspected.

Conclusion

The curative treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma remains challenging. Advances in hepatobiliary techniques have improved the perioperative and long-term survival outcomes of this tumor.

Keywords: Hilar cholangiocarcinoma, Negative margin, Hepatic resection, Vascular resection

Introduction

Hilar cholangiocarcinoma, or Klatskin tumor, is the most common malignant tumor affecting the extrahepatic bile duct. It is relatively slow growing and is usually small at clinical presentation. Only a very few patients with unresectable, indolent, and slow-growing hilar cholangiocarcinoma can have long-term survival [1]. The prognosis of most patients with unresectable tumor is poor because of the vital position of the tumor, with a median survival of less than 1 year. The treatment for hilar cholangiocarcinoma is challenging. Surgical resection remains the only potentially curative therapy. The survival rates for patients who had received R1 or R2 resection were significantly better than those with unresectable tumors [2–4]. In the old days, surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma aimed mainly at obtaining a diagnosis through laparotomy and relieving obstructive jaundice through surgical intubation or internal bypass [5]. In the past three decades, the extent of surgical resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma has shifted from local excision of the affected bile duct at the liver hilum with a local cone of adjacent liver parenchyma to more extensive resections involving combined major liver resection with increased long-term survival rates and decreased mortality and morbidity [6–10]. It is now widely accepted that resection of the bile duct cannot be accepted as a curative operation, and radical resection with combined hepatectomy is now adopted by most surgeons. The key strategy of surgical resection is to achieve adequate resection margins. This article focuses on the controversies in radical surgical resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma, including issues about the relevance of adequate resection margins, routine caudate lobe resection, extent of liver resection, and combined vascular resection on perioperative and long-term survival outcomes of patients with resectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Materials and methods

English medical literatures were extensively searched via online pubmed using the search strategy “hilar cholangiocarcinoma OR Klatskin tumor”. Studies focusing on curative surgical resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma were included. Case report and studies with less than 40 resections were excluded. Outcomes of surgical resection from 73 studies published during the period 1990–2014 were extracted and summarized in Table 1. Correlation was analyzed by Pearson’s test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 1.

Outcomes of resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma in series with more than 40 resections

| Authors | Published Year | Resections | R0 (%) | PH (%) | Mortality (%) | Morbidity (%) | 5-year survival (%) | R0 5-year survival (%) | PVR (%) | AR (%) | CR (%) | Resectablity* (%) | Bismuth III and IV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nimura et al. | 1990 | 55 | 84 | 93 | 11 | 35 | 38 | 41 | 25 | NA | 82 | 83 | NA |

| Gazzaniga et al. | 1993 | 48 | NA | NA | 23 | 79 | NA | 20 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ogura et al. | 1993 | 55 | 51 | 60 | 2 | 22 | 23 | NA | 9 | 2 | 51 | 96 | 69 |

| Sugiura et al. | 1993 | 83 | 57 | 100 | 8 | NA | 20 | 33 | 22 | 5 | 67 | NA | NA |

| Su et al. | 1996 | 49 | 49 | 57 | 10 | 47 | 15 | NA | 2 | NA | 22 | NA | 61 |

| Nakeeb et al. | 1996 | 109 | 26 | 14 | 4 | 39 | 11 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Klempnauer et al. | 1997 | 151 | 77 | 77 | 10 | NA | 28 | NA | 26 | 1 | 27 | NA | 82 |

| Miyazaki et al. | 1998 | 76 | 71 | 86 | 13 | 33 | 26 | 40 | 26 | 9 | 86 | NA | NA |

| Launois et al. | 1999 | 40 | 80 | 75 | 13 | 25 | 13 | NA | 18 | NA | 23 | 43 | 78 |

| Kosuge et al. | 1999 | 65 | 52 | 88 | 9 | 37 | 33 | NA | 5 | 5 | 83 | 73 | NA |

| Neuhaus et al. | 1999 | 80 | 55 | 83 | 8 | NA | 22 | 37 | 29 | NA | 83 | NA | 83 |

| Miyazaki et al. | 1999 | 93 | 70 | 86 | 10 | 38 | 26 | NA | 26 | 9 | 86 | NA | NA |

| Todoroki et al. | 2000 | 101 | 14 | 58 | 4 | 14 | 28 | 67 | NA | NA | NA | 89 | 70 |

| Lee et al. | 2000 | 111 | 78 | 100 | 6 | 48 | 22 | NA | 26 | 4 | 100 | NA | NA |

| Gerhards et al. | 2000 | 112 | 14 | 29 | 18 | 65 | NA | NA | 9 | 8 | NA | NA | 53 |

| Nimura et al. | 2000 | 142 | 76 | 90 | 9 | 49 | NA | 26 | 30 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Jarnagin et al. | 2001 | 80 | 78 | 78 | 10 | 64 | 27 | 30 | 11 | NA | 28 | 50 | NA |

| Kawarada et al. | 2002 | 87 | 64 | 75 | 2 | 28 | 26 | NA | NA | NA | 69 | 89 | NA |

| Shimada et al. | 2003 | 53 | 66 | 77 | 9 | 45 | 15–25 | 34 | 19 | 13 | 74 | 87 | 49 |

| Seyama et al. | 2003 | 58 | 64 | 100 | 0 | 43 | 40 | 46 | 16 | NA | 100 | 94 | 71 |

| Kawasaki et al. | 2003 | 79 | 68 | 96 | 1 | 14 | 22 | 40 | 6 | 3 | 87 | 75 | 78 |

| Kondo et al. | 2004 | 40 | 95 | 78 | 0 | 48 | NA | NA | 25 | 25 | 78 | 93 | 53 |

| Jitsma et al. | 2004 | 42 | 65 | 100 | 12 | 45 | 22 | 45 | 17 | 10 | 57 | NA | NA |

| Rea et al. | 2004 | 46 | 80 | 100 | 9 | 52 | 26 | 30 | NA | NA | 39 | NA | 85 |

| Ramesh et al. | 2004 | 46 | 70 | 76 | 7 | 28 | 22 | 25 | 7 | NA | 76 | 36 | 52 |

| Hemming et al. | 2005 | 53 | 80 | 98 | 9 | 40 | 35 | 45 | 43 | 6 | 98 | 66 | NA |

| Jarnagin et al. | 2005 | 106 | 77 | 82 | 8 | 62 | NA | NA | 9 | NA | 34 | 49 | NA |

| Dinant et al. | 2006 | 99 | 31 | 38 | 15 | 66 | 27 | 33 | 7 | NA | 15 | NA | 55 |

| Sano et al. | 2006 | 102 | 61 | 100 | 0 | 50 | 44 | NA | 22 | 5 | 100 | 92 | NA |

| Hasegawa et al. | 2007 | 49 | 78 | 90 | 2 | 47 | 40 | NA | 6 | 0 | 90 | NA | 84 |

| Baton et al. | 2007 | 59 | 68 | 100 | 5 | 42 | 20 | 28 | 8 | 2 | 100 | NA | NA |

| Hidalgo et al. | 2008 | 44 | 45 | 93 | 7 | 59 | 28 | 45 | 45 | 9 | 77 | 90 | NA |

| Konstadoulakis et al. | 2008 | 59 | 66 | 86 | 7 | 25 | 34 | NA | 24 | NA | 64 | 81 | 86 |

| Endo et al. | 2008 | 101 | 81 | 82 | 5 | NA | 31 | NA | 9 | NA | 36 | NA | NA |

| Murakami et al. | 2009 | 42 | 74 | 86 | 7 | 52 | 30 | NA | NA | NA | 90 | NA | NA |

| Young et al. | 2009 | 51 | 57 | 92 | 8 | 75 | 20 | 40 | 41 | 10 | 92 | NA | 92 |

| Miyazaki et al. | 2009 | 107 | 59 | 91 | 2 | NA | 28 | 33 | 23 | 3 | NA | NA | 83 |

| Chen et al. | 2009 | 138 | 89 | 100 | 0 | 30 | 27–34 | NA | 33 | NA | 92 | 74 | 67 |

| Hirano et al. | 2009 | 146 | 87 | 88 | 3 | 44 | 36 | NA | 45 | 14 | 88 | NA | 62 |

| Giuliante et al. | 2010 | 43 | 77 | 93 | 7 | 53 | 36 | NA | NA | 1 | NA | 29 | NA |

| Ercolani et al. | 2010 | 51 | 73 | 100 | 10 | 51 | 34 | 44 | 8 | 4 | 78 | 82 | 100 |

| Rocha et al. | 2010 | 60 | 80 | 78 | 5 | 35 | NA | 54 | NA | NA | 48 | 57 | NA |

| Gulik et al. | 2010 | 99 | 31 | 38 | 10§ | 68§ | NA | NA | 18 | NA | 39 | NA | NA |

| Kobayashi et al. | 2010 | 119 | 66 | 92 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Unno et al. | 2010 | 125 | 63 | 95 | 8 | 49 | 35 | 45 | 34 | 3 | 100 | NA | 80 |

| Igami et al. | 2010 | 298 | 74 | 98 | 2 | 43 | 42 | 52 | 37 | 18 | 98 | NA | 88 |

| Lee et al. | 2010 | 302 | 71 | 89 | 2 | NA | 33 | 47 | 13 | 2 | 89 | 86 | 81 |

| Gulik et al. | 2011 | 41 | 92 | 85 | 7 | NA | NA | NA | 22 | NA | 78 | NA | 78 |

| Saxena et al. | 2011 | 42 | 64 | 100 | 2 | 45 | 24 | NA | 26 | 5 | 36 | 78 | 79 |

| Chauhan et al. | 2011 | 51 | 73 | 76 | 12 | 69 | 29 | NA | 6 | NA | 8 | NA | NA |

| Guglielmi et al. | 2011 | 62 | 74 | 87 | 10 | 55 | 15 | NA | 16 | 3 | 76 | NA | NA |

| Hemming et al. | 2011 | 95 | 84 | 100 | 5 | 34 | 43 | 50 | 44 | 5 | 100 | NA | 89 |

| Neuhaus et al. | 2011 | 100 | NA | 100 | 11–12 | NA | 43 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 90 |

| Otto et al. | 2011 | 123 | 79 | 89 | 6 | NA | 26 | NA | 38 | NA | 89 | 77 | 91 |

| Li et al. | 2011 | 215 | 66 | 95 | 5 | NA | 30 | 41 | 16 | 6 | NA | 73 | 41 |

| Ruys et al. | 2012 | 57 | 75 | 88 | NA | NA | 42 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 60 | NA |

| Cannon et al. | 2012 | 59 | 63 | 83 | 5 | 39 | NA | 58 | NA | NA | NA | 54 | NA |

| Cho et al. | 2012 | 105 | 71 | 78 | 14 | NA | 34 | 50 | 8 | NA | 59 | NA | 81 |

| Kow et al. | 2012 | 127 | 89 | 97 | 2 | 6 | 30–66 | NA | NA | NA | 55 | NA | 100 |

| Matsuo et al. | 2012 | 157 | 76 | 82 | 8 | 59 | 32 | 36 | 10 | NA | 36 | 53 | NA |

| Lee et al. | 2012 | 162 | 77 | 81 | 1 | NA | 42 | 45 | 6 | 2 | 76 | 66 | 69 |

| Cheng et al. | 2012 | 171 | 78 | 100 | 3 | 26 | 14 | 17 | 13 | 3 | 80 | 61 | 100 |

| de Jong et al. | 2012 | 305 | 65 | 73 | 12 | NA | 20 | 25 | 17 | NA | NA | NA | 44 |

| Nuzzo et al. | 2012 | 440 | 77 | 85 | 9 | 37 | 26 | 32 | 8 | 2 | 67 | NA | 59 |

| Nagino et al. | 2012 | 574 | 77 | 97 | 5 | 57 | 33 | NA | 36 | 13 | 97 | 90 | 85 |

| Song et al. | 2013 | 230 | 77 | 78 | 4 | NA | 33 | 40 | 10 | 1 | 44 | 100 | 70 |

| Dumitrascu et al. | 2013 | 90 | 76 | 73 | 8 | 53 | 27 | 31 | 13 | 3 | 50 | 69 | 76 |

| Farges et al. | 2013 | 366 | NA | 100 | 11 | 69 | NA | NA | 23 | NA | NA | NA | 78 |

| Gomez | 2014 | 57 | 74 | 86 | 14 | 60 | 40 | NA | 9 | 4 | 86 | 67 | NA |

| Yu | 2014 | 238 | 50 | 51 | 1 | 18 | 17 | NA | 11¶ | 20 | NA | NA | 86 |

| Furusawa et al. | 2014 | 144 | 74 | 99 | 1 | 73 | NA | NA | 15 | 3 | 100 | NA | 78 |

| Tamoto | 2014 | 49 | 82 | 100 | 4 | 63 | NA | NA | 73 | NA | 100 | NA | NA |

*Data indicates percentage of resections in patients explored with curative intent

§In the last period (1998–2003, n = 29)

¶Data indicates percentage of portal vein resections in R0 resections

PVR indicates portal vein resecion

AR artery resecion; CR caudate lobe resecion; NA data not available

Results and discussion

Tumor-free resection

The most important factor affecting long-term survival in the surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma is whether the tumor has been completely resected on histological examination (R0 resection). The margin status include R0 margin (no residual tumor), R1 margin (microscopic residual tumor), and R2 margin (macroscopic residual tumor). Patients with R1 margin or R2 margin have a dismal survival [11, 12]. Of the many clinicopathological factors affecting long-term survivals, R0 resection is the only factor which can be modified by the surgeon. Thus, the primary goal of surgical therapy is to achieve R0 resection [13].

Several reports have suggested that the long-term survivals after R0 and R1 were not significantly different [14–16]. There is a possibility that in these reports, some of the patients with R1 resection were mistakenly classified as R0 resection because there was no adequate sampling of the margins, especially in patients with narrow resection margins. Endo et al. classified their patients who have received R0 resection into the wide margin group and the narrow margin group. Of all the patients with R0 bile duct margins shown intraoperatively, only 60 % were associated with improvement in disease-specific survival when compared with patients with R1 resections. While the group of patients with wide margin experienced better, the group of patients with narrow margin had similar disease-specific survival similar to those patients who underwent R1 resection [17]. Similarly, Seyama et al. found that patients with surgical tumor-free margin of over 5 mm resulted in significantly better long-term survival than those patients with a margin of less than 5 mm. However, there was no difference between the survival of patients after R0 resection with those who had a narrow margin (<5 mm) or those who had received R1 resection [15]. The wider and the longer the resection margin, the less likely it is to find a positive resection margin [18]. Thus, wide and long R0 margins are required for resection with curative intent in hilar cholangiocarcinoma resectional surgery.

It is frequently difficult to achieve a wide and long resectional margin for curative treatment. First, hilar cholangiocarcinoma is located in the liver hilum surrounded by vital structures. Second, it is difficult to determine the exact length and width of microscopic tumor extension preoperatively and intraoperatively. The biological nature of cholangiocarcinoma involves proximal microscopic spread of the disease along the bile duct extending beyond the palpable macroscopic boundaries of the primary hilar mass. Sakamoto et al. histologically examined serial sections of 62 specimens of resected hilar cholangiocarcinoma. They found that anastomotic recurrences never occurred in patients who had a proximal tumor-free resection margin greater than 5 mm, suggesting that a 5 mm tumor-free margin was adequate for curative intent [19]. However, it has been demonstrated that the longitudinal extent of tumor at the proximal border ranged from 0.6 to 18.8 mm in the submucosa layer [19], and that the width of the superficial extension showed a wide distribution of 31–52 mm [18, 19]. Surgeons, thus, cannot be certain on the length and width of the resection margins. Third, intraoperative frozen-section examination of ductal margins has an accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of only 56.5, 75.0, and 46.7 %, respectively [20].

Nonetheless, to achieve real R0 resection, transection of the proximal bile duct above the macroscopic border of the primary tumor should be carried out as high as technically feasible with careful consideration of the potential morbidity, and resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma combined with major hepatectomy has the potential to provide wide and long resection margins on the ipsilateral side of the combined liver resection [17].

Further resection

The recent reported incidences of positive resection margins in patients who had undergone surgical resection with curative intent ranged from 64.6 to 88.2 % at high-volume centers [4, 10, 14, 21–23]. When a positive resection margin is diagnosed intraoperatively using frozen section examination, further resection is recommended if technically possible to obtain complete tumor removal [11, 12, 24]. However, further resection of the bile duct at the proximal side can be technically difficult due to encroachment onto vital structures and adjacent liver parenchyma [2, 25, 26]. Not every patient with R1 resection can be subjected to further resection [17, 25]. For patient who can be further resected because of technically feasibility or no radial tumoral invasion, 54 to 83 % can achieve R0 resection [12, 14, 17, 25]. Unfortunately, the clinical usefulness of further resection has not yet been established, and it is still controversial whether further resection improves patients’ survival [12, 14, 17, 25]. While several reports have suggested that further resection did not contribute to improvement in survival [14, 17] probably because of the limited further length of less than 5 mm that could be resected [25], Ribero and colleagues achieved good results in 15 secondary negative margins in 18 additional resections [12]. Unfortunately, they did not record the exact length of further bile duct resection. However, they demonstrated that the survival of patients who had a secondary R0 resection was similar to that of the primarily R0-resected patients, and they were significantly better than those patients with R1 resection. They also showed similar median survival to recurrence and similar incidence of local site recurrence when patients with R1 resection were compared with patients with R0 resection, independent of whether further resection was carried out [12]. Notably, the primary essence of further resection is to obtain tumor-free margins wide and long enough for curative intent. It is recommended that more extended resections with adequate surgical margins should be carried out when technically possible and when the patient has good functional reserves [25]. To further address these issues, randomized controlled studies with adequate patients are required, and the adequate length of bile duct resection should be carefully defined to provide more convincing data.

Hepatic resection

In the old days, hilar cholangiocarcinoma had been considered to be unresectable and palliative decompression of the obstructed biliary tract using bypass surgery or tube-drainage was popularly employed. Surgical resections with curative intent were later attempted to achieve better survival [27–31]. Both local resection of bile duct and resection combined with major hepatectomy were used. The surgical strategy was made according to the location and involvement of the tumor mass. When the tumor was small or localized, the tumor was resected together with an adjacent cone of liver parenchyma. If it infiltrated into the liver parenchyma, combined major liver resection was carried out [24, 27, 32, 33].

In 1990, a review on 581 resections for hilar bile duct cancer was published: 245 patients (42.2 %) received local bile duct confluence resection while 224 (38.6 %) patients received resection of the bile duct confluence combined with major liver resection [34]. Tumor cells from hilar cholangiocarcinoma are apt to infiltrate along the bile duct wall and invade into the surrounding vital structures as well as the adjacent liver parenchyma because the confluence of the bile ducts has thin walls and it is strategically situated. Even as early as the 1980s [7, 31, 34], surgeons started to hold the view that hilar cholangiocarcinoma should be regarded more as a regional than a local disease. As a consequence, an increasing number of combined major liver resections were performed [34]. However, there was no survival benefit at that time using bile duct resection combined with major hepatectomy when compared with local resection of a cone of adjacent liver parenchyma [33, 35]. The increase in 5-year survival rate from 6 % for local resection to 14 % for major liver resections was almost completely offset by the increase in postoperative mortality from 9 % for local resections to 17 % for major liver resections [34]. Also, the mean survival time [34] as well as the R0 resection rate [33, 35] had hardly been improved by the use of combined major liver resection.

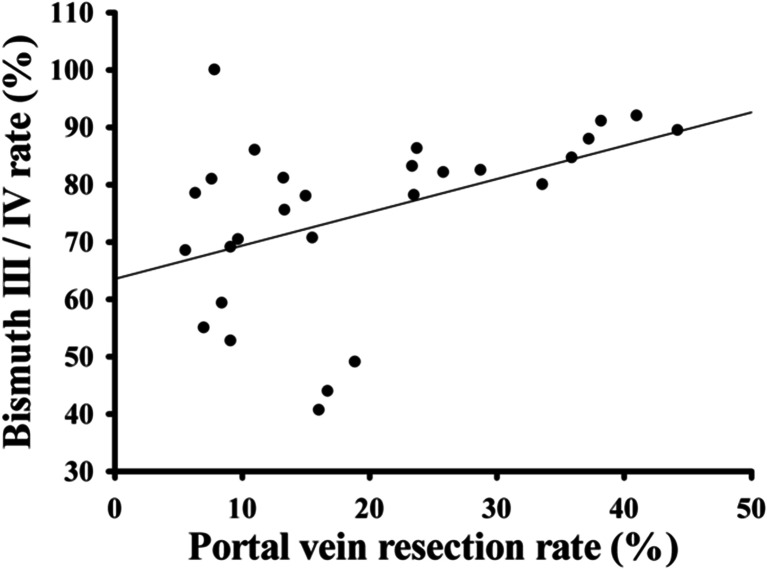

Over the last two decades, complex and aggressive surgical resections were made possible with acceptable morbidity and mortality rates by major advances in patient selection, radiologic assessment, surgical techniques, and perioperative care [21, 33, 36–41]. At the same time, there are more evidences to support bile duct resection with an adjacent cone of liver parenchyma cannot be accepted as an adequate curative treatment, and combined major hepatic resection is associated with improved survival [38, 39, 42–44]. The main aim of the aggressive surgical approach is to obtain R0 resection. Figure 1 shows that the percentage of hilar cholangiocarcinoma resected with combined major hepatic resection in surgical series is positively correlated with the tumor-free resection margin rate. Most reports coming from single center studies indicated that there was a progressive increase in proportion of patients submitted to combined major hepatic resection with an increased R0 resection rate and improved survival over the study period [3, 37, 45–50] (Table 2). Bile duct resection combined with major hepatic resection has now been increasingly accepted as a standard surgical treatment for hilar cholangiocarcinoma [51].

Fig. 1.

Positive correlation of hepatic resection rates and tumor-free margin achievement. Data were extracted from Table 1

Table 2.

Surgery outcomes according to the time period in several series from single centers

| Authors | Published year | Time period | Resections | R0 (%) | PH (%) | Mortality (%) | Morbidity (%) | 5-year survival (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gerhards et al. | 2000 | 1983 | −1987 | 42 | 5 | 36 | 19 | 66 | NA |

| 1988 | −1992 | 45 | 13 | 9 | 20 | 73 | NA | ||

| 1993 | −1997 | 25 | 32 | 52 | 12 | 52 | NA | ||

| Kawarada et al. | 2002 | 1976 | −1993 | 62 | 55 | 65 | 2 | 31 | 20 |

| 1994 | −2000 | 25 | 88 | 100 | 4 | 20 | 50 | ||

| Dinant et al. | 2006 | 1988 | −1993 | 45 | 13 | 9 | 20 | 73 | 22 |

| 1993 | −1998 | 25 | 32 | 52 | 12 | 52 | 35 | ||

| 1998 | −2003 | 29 | 59 | 72 | 10 | 68 | 59 | ||

| Gulik et al. | 2010 | 1988 | −1993 | 45 | 13 | 9 | NA | NA | 20 |

| 1993 | −1998 | 25 | 32 | 52 | NA | NA | |||

| 1998 | −2003 | 29 | 59 | 72 | 10 | 68 | 33 | ||

| Nagino et al. | 2012 | 1977 | −1990 | 72 | 75 | 92 | 11 | 76 | 23 |

| 1991 | −2000 | 116 | 93 | 10 | 80 | ||||

| 2001 | −2005 | 168 | 78 | 98 | 3 | 52 | 38 | ||

| 2006 | −2010 | 218 | 99 | 1 | 43 | ||||

| Furusawa et al. | 2014 | 1990 | −2000 | 70 | 70 | 99 | 1.4 | 85.7 | 33 |

| 2001 | −2012 | 74 | 78 | 100 | 0 | 61 | 35 | ||

NA indicates data not available

Is hepatic resection necessary for type I or II hilar cholangiocarcinoma

Even though combined major hepatic resection is widely accepted for Bismuth type III and IV hilar cholangiocarcinoma, whether it is necessary for type I or II tumor is still controversial. A number of researchers consider that tumor resection with an adjacent cone of liver parenchyma is sufficient for patients with type I or II tumor [10, 52–55] especially for type I tumors [10, 21, 56, 57]. Launois et al. performed combined major hepatectomy depending on two factors: tumor location and TNM classification [58]. They performed local hilar resection mainly for Bismuth I or II tumors with Tis and T1 lesions and the survival seemed better than that of combined major hepatectomy which was done mainly for Bismuth III or IV tumors, suggesting that local hilar resection is sufficient if the tumor is Bismuth I or II [58]. Similarly, Otani et al. compared local hilar resection for Bismuth type I or II tumors with T2 or less lesions with combined major hepatectomy for type III or IV tumors and found that similar R0 resection rates as well as cumulative survivals were equally achieved in the two groups [59]. They concluded that local hilar resection was indicated for papillary T1 or T2 tumors in Bismuth type I or II tumor [59]. However, there are limited data to assess the effectiveness of combined major hepatic resection for type I or II tumor in these studies, and it is difficult for a surgeon to get the precise information on the tumor classification or the TNM staging preoperatively or intraoperatively [60]. Ikeyama et al. compared survival in patients with nodular and infiltrating hilar cholangiocarcinoma who tolerated right hemihepatectomy with survival in patients who tolerated bile duct resection with or without limited hepatic resection, and recommended that the surgical approach to Bismuth type I and II hilar cholangiocarcinoma should be determined according to preoperative cholangiographic features. For nodular and infiltrating hilar cholangiocarcinoma, right hepatectomy is essential for cure, for papillary tumor local resection with or without limited hepatic resection is adequate [48]. A more recent retrospective study, which aimed to evaluate surgical outcomes of bile duct resection alone and combined major liver resection in 52 patients with Bismuth type I and II hilar cholangiocarcinoma, revealed that concomitant liver resection had a higher curability, lower local recurrence rate, and better overall survival with a similar postoperative morbidity and mortality [61]. In addition, the authors found that cancer recurred in three patients out of the six R0 resectional papillary tumors treated by bile duct resection alone [61]. It seems that concomitant liver resection should be considered in all patients with Bismuth type I and II hilar cholangiocarcinoma regardless of the tumor classification. Several types of hepatic resections were performed in that study, including left or right hepatectomy or volume-preserving liver resection [61]. In our experience, central hepatectomy resecting segment 5 and segment 4b/extended 4b resection is the primary choice for type I and II tumors [62]. This operation is adequate for both negative resection margins and good exposure. Properly conducted prospective randomized controlled trials are needed to validate the treatment strategy for type I and II hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Routine caudate lobe resection

The caudate lobe is located deep in the liver between the inferior vena cava and the hepatic hilum, thus isolation and resection of the caudate lobe remain a challenge for surgeons. The importance of tumor involvement of the caudate lobe in the treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma had not been fully recognized two decades ago. Some surgeons do not adopt a strategy of routine caudate lobe resection even now [33, 35], mainly due to the deep anatomical location of the caudate lobe and the concern on postoperative insufficient remnant liver parenchyma. The result was dismal. Bengmark et al. employed major liver resections in 100 % of the 22 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma from 1968 to 1984; however, they did not emphasize the inclusion of caudate lobe resection in the surgical procedure [7]. R0 resection was achieved just in 18.2 % of the patients [7].

The close anatomic relationship between the caudate lobe and the hilar cholangiocarcinoma was well studied by Mizumoto et al. in 1986 [63]. As hilar cholangiocarcinoma has a high chance to invade the biliary branches or directly infiltrate the parenchyma of the caudate lobe [38–40, 64], routine caudate lobe resection should be carried out for curative treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma [63]. Better R0 resection rates and higher cumulative survival rates are achieved by concomitant caudate lobe resection [9, 39, 49]. At present, caudate lobe resection is increasing carried out for hilar cholangiocarcinoma all over the world [9, 45, 49, 65]. Table 1 shows that, for the period of 2006 to 2014, there were 3447 caudate lobe resections in 4577 patients with surgical resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma, which are significantly higher than the percentage of caudate lobe resection carried out from 1980 to 2005 (Fig. 2). Two retrospective studies published in 2012 aimed primarily to assess the specific role of routine caudate lobe resection for Bismuth type III/IV hilar cholangiocarcinoma found total caudate lobectomy contributed to improvement in survival [22, 66]. The role of routine caudate lobe resection in Bismuth type I/II tumors is still uncertain.

Fig. 2.

Caudate lobe resection rate according to the time period. Data were extracted from Table 1

Nimura et al. reported in 1990 that 98 % of caudate lobe resections were histologically confirmed to be tumor positive [64]. However, other authors reported that the caudate lobe was involved in hilar cholangiocarcinoma in 32.4 ± 7.1 % (mean ± standard deviation) [38, 39, 45, 62, 67, 68]. It is our opinion that it should be routine as at least one third of patients had the caudate lobe involved by hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Major liver resection or minor liver resection

There are still controversies on the optimal extent of hepatic resection to achieve a high percentage of R0 resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Combined major liver resection represents an aggressive surgical approach to remove a large volume of hepatic parenchyma, including the use of right trisectionectomy (Couinaud segment 1, 4–8), right hemihepatectomy (S1, 5–8), left trisectionectomy (S1–5, S8), or left hemihepatectomy (S1–4). This approach has widely been advocated as a prime choice of surgical treatment for hilar cholangiocarcinoma, especially in patients with advanced tumors [69–71]. It is believed that combined major liver resection has the advantage to increase surgical curability by obtaining wide and negative surgical resection margins [72, 73]. In addition, hemihepatectomy/trisectionectomy is technically feasible and can be carried out by many surgeons. The major drawback of combined major liver resection is the small postoperative liver remnant which is associated with high surgical morbidities and mortalities [44, 49, 74, 75]. Dinant et al. reported hospital morbidity of 70.3 % (26/37) and mortality of 21.6 % (8 dead in 37) in patients after hemi- or extended hemihepatectomy [49]. Similarly, Ramesh et al. and Gerhards et al. reported that the overall mortality rate was 25 % (3/12 and 8/32, respectively) after major liver resections resulting in postoperative liver failure [50, 75]. Thus, the increase in resectability rate can be offset by the increase in postoperative mortality after associated major liver resection. Some approaches have been proposed to reduce the perioperative risk of associated major liver resection, including adequate assessment of the volume/function of the future remnant liver, preoperative biliary drainage, and portal vein embolization (PVE). Kawasaki et al. showed an in-hospital mortality rate as low as 1.3 % could be achieved after extended, mainly right, hepatectomy with routine preoperative biliary drainage and hemihepatic PVE [60]. Preoperative PVE is thought to be effective to induce hypertrophy in the remnant liver and thus may increase safety for patient who is considered insufficient in remnant liver volume. However, the benefit of preoperative biliary drainage and PVE has not been fully recognized and consensus of indication criteria has not yet been established [52, 60, 71, 76–78]. PVE procedure may delay the surgical resection and associate with rapid tumor growth or liver metastases. Besides, the estimated blood loss and operation time were reported significantly higher in PVE group [52].

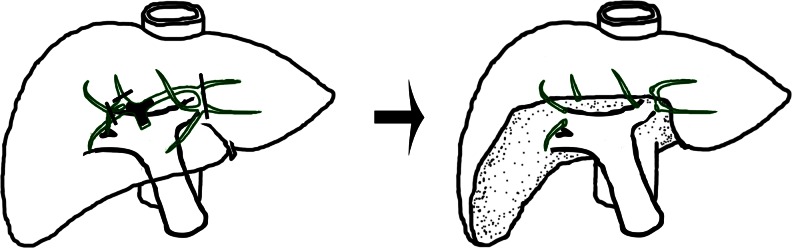

In the late twentieth century, Nimura and Miyazaki advocated using minor central hepatic resection in carefully selected patients to preserve as much as possible the functional liver volume [44, 64]. Limited central liver resection means excision of liver segments/subsegments around the liver hilum, such as segment 1 resection, segment 1 and 4 (4b) resection, segment 1, 4 (4b), and 5 resection, or mesohepatectomy (segment 1, 4 (4b), 5, and 8 resection). We believe that this approach should take an important part in surgical treatment for most of the hilar cholangiocarcinoma. First, a large amount of liver parenchyma involved in combined major liver resection is free of tumor and it is not necessarily to resect these liver tissues. Based on a three-dimensional perception of the tumor located centrally in the liver, the aim of the curative resection is to resect adequately the bile duct bifurcation with the adjacent liver parenchyma. Generally, resection of segment 1, 4 (4b), and 5 is adequate. The extent of liver resection can occasionally be modified to include partial segment 6, 7, and 8 if necessary (Fig. 3). Minor central liver resection can be performed in patients with type I, type II, type IIIa, and type IIIb tumors [62] and even for type IV tumors [56]. Second, although there are some concerns that minor central liver resection may decrease the rate of curative surgical resection, the Japanese surgeons have shown clearly that surgical curability and postoperative survival rates in selected patients with minor central hepatic resection were not compromised and surgical morbidity/mortality rate was significantly lower than that in the combined major liver resection group [44, 79, 80]. Similarly, patients who received minor central liver resection had good perioperative outcomes (9.7 % morbidity and 0 % mortality) with no decreased long-term survival rates (5-year survival rates were 34 % for minor resection vs. 27 % for major resection) [62]. One should be noticed that there is an intrinsic limitation in these retrospective studies. Patients submitted in major or minor resection groups were not randomized controlled. Select bias occurred when the surgeons made the decision of surgical strategy. Minor resections tend to be chosen for type I to III tumors or tumors confined to the first-order hepatic duct. Thus, it is difficult to tell the differences of these two surgical strategies in a tumor with a certain bismuth type or T stage. More recently, a technique of modified extended liver resection which aimed to reduce the removal of the amount of functional liver parenchyma has been described with a R0 resection rate of 92 % and an overall mortality rate of 7 % [81]. In this strategy, segment 4a was preserved in extended right hepatectomy and a modified extended left hepatectomy was performed by preserving the bile duct of segment 8 with its associated parenchyma on the cranial side. The authors also employed mesohepatectomy as an alternative to extended right hepatectomy for Bismuth type IIIa and IV tumors, when tumor infiltration into the ducts of segments 6 and 7 was limited and the right hepatic artery was not involved [81]. Third, even though minor central liver resection is technically more difficult than the other types of major liver resections because of the many intrahepatic ductal openings that need to be anastomosed, we have described a special technique of hepaticojejunostomy to solve this problem [62].

Fig. 3.

Minor liver resection. Liver parenchyma adjacent to the liver hilum, including segment 1, 4b, 5, and part of segment 6, 7, 8, is resected. Resection of segment 4b and 5 provides good exposure

The lack of consensus on the extent of liver resection seems to arise mainly from the difficulty in precisely determining the extent of the proximal tumor preoperatively and intraoperatively. Kawasaki et al. argued against minor central liver resection and claimed that major hepatectomy should be performed for all patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma because of the limitations of the currently available preoperative diagnostic modalities [60]. Some surgeons thought minor central liver resection should be limited strictly to patients with T2 tumor which has not invaded beyond any of the segmental hepatic ducts [44, 50, 62, 80]. Central minor liver resection carried out departing from these principles may result in poor survival outcomes. Indeed, minor central liver resections with curative intent should only be applied after precise anatomical assessment of the biliary tract with adequate assessment of the extent of tumor [44, 81]. The dilemma between major liver resection with potential postoperative liver failure and central minor liver resection with potential positive resection margins might be solved by advances in preoperative assessment. Concomitant use of three dimension and multiplanar reconstruction images using multidetector row computed tomography data can precisely detect both longitudinal and vertical tumor invasion [82]. This technique is noninvasive and can improve the curative resection rate, which might reduce the risk of positive margin even in minor liver resection. Sasaki et al. estimated length of proximal hepatic ducts using this technique, and found 17 in 18 hepatic ducts (94 %) were diagnosed negative [83]. However, this technique has not yet been evaluated in minor liver resections to our knowledge. Further advances in sensitivity of this technique are expected and may provide the hope to determine the extent of surgical resection for a tumor in a patient.

Left- or right-sided hepatectomy

The decision of whether right- or left-sided hemihepatectomy is indicated is made according to the predominant site of the lesion. In general, right hemihepatectomy can be applied to type IIIa tumors and IV tumors when the lesion is predominantly located in the right hepatic duct; whereas left hemihepatectomy can be applied to type IIIb tumors and IV tumors with left-sided predominance [60, 84, 85].

Right or extended right hemihepatectomy, the most radical surgical procedure, is routinely adopted by many surgeons on the basis of several anatomical considerations for patients with centrally situated hilar cholangiocarcinoma which can be treated by either combined right or left hemihepatectomy [8, 42, 51, 60, 86]. First, the extrahepatic part of the left hepatic duct is longer than the right hepatic duct, and the distance from the bifurcation to the sectional duct ramification is also much longer in the left liver. Second, the hepatic duct confluence lies on the right side of the hepatic hilum. Third, the right hepatic artery generally runs behind the common hepatic duct, and it is more likely to be invaded by tumor. Fourth, the left portal vein is also longer than the right portal vein. Finally, there are many anatomic variations which can jeopardize the safe performance of left-sided hepatectomy [87]. Therefore, right-sided hepatectomy is thought to be technically easier and has the additional advantage of radicality [42, 60, 88]. It is also emphasized that right-sided hepatectomy has superiority because it enabled en-bloc resection of the hepatic ductal confluence and its surrounding structures [89, 90]. In a right-sided hepatectomy predominated study, extended left hepatectomy was only occasionally performed as an alternative because of insufficient remnant liver volume [60]. Recently, Neuhaus et al. described the hilar en-bloc resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma which comprises of resecting en bloc the portal vein bifurcation, the right hepatic artery, and liver segments 1 and 4 to 8, and showed its oncological superiority to the conventional combined major hepatectomy [91].

The major drawback of the right-sided hepatectomy is loss of a large volume of liver mass. Farges et al. reported a higher mortality rate after right-sided hepatectomy than left-sided hepatectomy [76]. Some surgeons also prefer left-sided hepatectomy because segment 4, an anatomical part of the left liver [81], is potentially invaded by tumor. By routinely resection segment 4, left-sided hepatectomy preserves more liver parenchyma than the right-sided approach (with only segment 2 and 3 remaining) [46].

Even though right-sided hepatectomy is the preferred approach for hilar cholangiocarcinoma [21], if there is a choice, in some series, left- or right-sided hepatectomies were carried out in a comparable number of patients [38, 52, 92]. In a recently large series published by Nagino et al. on 574 patients, left-sided hepatectomy contributed more than right-sided hepatectomy (51.8 vs. 38.3 %) [79]. In that cohort, type IV tumor took 45.5 % of all the cases and type III took 39.2 %. It seems that the author may prefer left-sided hepatectomy even for type IV tumors.

Shimuzu et al. performed left-sided hepatectomy for Bismuth type IIIb tumors in 88 patients and right-sided hepatectomy for type IIIa and IV tumors in 84 patients and showed equivalent operative curability and postoperative long-term survival between patients undergoing left-sided hepatectomy and right-sided hepatectomy [88]. Similarly, in a recent series reported by Lim et al., survival and recurrence rates after left hepatectomy were not significantly different from right hepatectomy in patients with type I and II hilar cholangiocarcinoma [61]. Further studies are required to identify the treatment strategy for type IV hilar cholangiocarcinoma between right- and left-sided hepatectomy.

Combined vascular resection

The anatomical location of hilar cholangiocarcinoma is close to the portal vein bifurcation and the hepatic artery. These vascular structures are often invaded by tumor. The involvement of these vascular structures calls for combined vascular resection to achieve R0 resection. The indications for combined vascular resection include intraoperative suspicion of gross tumor invasion to the vessels [43, 93, 94], tight adherence of the tumor to the vessels during vascular skeletonization [8, 22, 55] and routine resection of portal vein in systematic radical surgery as advocated by some authors [10]..

Concomitant hepatic arterial resection and reconstruction should be performed with caution because it may result in higher morbidity and mortality rates but without any proven survival benefit [95]. Recent three meta-analyses draw similar conclusions that portal vein resection does not affect on postoperative mortality [95–97]. This consensus needs to be carefully interpreted. First, Wu et al. conducted the conclusion from subgroup analysis including studies from experienced surgeons and those published after 2007 [97]. Second, Abbas et al. draw the conclusion in an indirect manner. They found that the increase in mortality in patients who received vascular resection resulted from concomitant hepatic arterial resection, thus supposed that portal vein resection had no impact on postoperative mortality [95]. Another similar conclusion from these studies is that portal vein resection does not increase morbidity [95–97], and there is only occasional postoperative portal vein thrombosis (Table 3). Thus, portal vein resection can be performed safely. However, patients in portal vein resection cohort have lower 5-year survival rates. At first sight, the value of portal vein resection is limit for hilar CC patients with portal vein involvement. One should notice that patients who received portal vein resection had significantly higher rates of advanced disease (T3 and T4) when compared with patients without portal vein involvement [10, 95, 97], and they tended to have Bismuth III or IV tumors (Fig. 4). The importance of portal vein resection should be revealed by investigating the impact of portal vein resection on the surgical results for patients with the same tumor stage and Bismuth type.

Table 3.

Complications related to portal vein resection

| Authors | Published year | Resections (n) | PVR (n) | Outcomes of PVR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klempnauer et al. | 1997 | 151 | 39 | Three portal vein thrombosis |

| Neuhaus et al. | 1999 | 80 | 23 | Do not associate with mortality |

| Gerhards et al. | 2000 | 112 | 10 | Significant predictors of increased mortality. |

| Capussotti et al. | 2002 | 36 | 5 | Do not associate with morbidity and mortality |

| Kawasaki et al. | 2003 | 79 | 5 | Do not associate with survival |

| Seyama et al. | 2003 | 58 | 9 | Do not associate with survival |

| Dinant et al. | 2006 | 99 | 7 | Do not associate with morbidity and mortality |

| Hasegawa et al. | 2007 | 49 | 3 | Do not associate with survival |

| Konstadoulakis et al. | 2008 | 59 | 14 | Do not associate with morbidity and mortality |

| Yong et al. | 2009 | 51 | 21 | Zero mortality, and 1 portal vein thrombosis |

| Lee et al. | 2010 | 302 | 40 | Zero mortality, and 1 portal vein thrombosis |

| Igami et al. | 2010 | 298 | 111 | Five portal vein thrombosis |

| Hemming et al. | 2011 | 95 | 42 | Do not associated with mortality |

| Nagino et al. | 2012 | 574 | 206 | Do not associated with mortality |

| de Jong et al. | 2012 | 305 | 51 | Increase perioperative risk (mortality) |

| Song et al. | 2013 | 230 | 22 | One portal vein thrombosis |

| Gomez et al. | 2014 | 57 | 5 | One portal vein thrombosis |

| Yu et al. | 2014 | 119 | 25 | Had no effect on patient survival |

| Tamoto et al. | 2014 | 49 | 36 | Do not associate with post-operative complications. |

PVR portal vein resection

Fig. 4.

Portal vein resection rate significantly correlate with Bismuth type. Data were extracted from Table 1

The histological involved margin status seems more important than the presence of direct invasion/involvement of portal vein for long-term overall survival [10]. Even the role of portal vein resection on R0 margin rates is still controversial [95–97], logically portal vein resection allows patients who had advanced tumor a chance to achieve a better histological result. Therefore, when portal vein invasion is suspected, combined portal vein resection should be carried out. This conclusion is further supported by a recent international, multicenter, retrospective study on a large cohort of patients [10].

The reported rates of actual tumor invasion into the resected vessels varied from 22 to 100 % [8, 10, 90, 93, 94, 98–100]. This indicate that it is difficult to determine the actual status of vascular involvement preoperatively or intraoperatively and that the indication of portal vein resection is quite variety. Therefore, some Japanese surgeons advocated routine portal vein resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma to achieve better long-term survival [4, 8, 91, 101]. However, the benefit of routine portal vein resection requires further evidence to support [5, 13, 95].

Conclusion

Treatment for hilar cholangiocarcinoma remains challenging. In order to improve surgical outcomes for patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma, strategy of surgical resection with curative intent has improved over the years. Some consensuses have been reached, including R0 margin achievement, routine caudate lobe resection, combination of partial hepatectomy, and portal vein resection when involved by tumor. However, there are still several controversial issues need to be further clarified. Improvement of hepatobiliary imageological technique that can provide more accurate information of the tumor extent preoperatively will offer help. Due to the rarity of hilar cholangiocarcinoma, prospective randomized studies can only be carried out in multiple centers.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by the Hepatic surgery clinical study center of Hubei province, China (2014BKB089).

References

- 1.Ruys AT, van Haelst S, Busch OR, Rauws EA, Gouma DJ, van Gulik TM. Long-term survival in hilar cholangiocarcinoma also possible in unresectable patients. World J Surg. 2012;36(9):2179–2186. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1638-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiffman SC, Reuter NP, McMasters KM, Scoggins CR, Martin RC. Overall survival peri-hilar cholangiocarcinoma: R1 resection with curative intent compared to primary endoscopic therapy. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105(1):91–96. doi: 10.1002/jso.22054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cannon RM, Brock G, Buell JF. Surgical resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Experience improves resectability. HPB (Oxford) 2012;14(2):142–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Igami T, Nishio H, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Sugawara G, Nimura Y, Nagino M. Surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma in the “new era”: the Nagoya University experience. JHepato-Biliary-Pancreat Surg. 2010;17(4):449–454. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lau SH, Lau WY. Current therapy of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2012;11(1):12–17. doi: 10.1016/S1499-3872(11)60119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tompkins RK, Thomas D, Wile A, Longmire WP., Jr Prognostic factors in bile duct carcinoma: Analysis of 96 cases. Ann Surg. 1981;194(4):447–457. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198110000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bengmark S, Ekberg H, Evander A, Klofver-Stahl B, Tranberg KG. Major liver resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1988;207(2):120–125. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198802000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuhaus P, Jonas S, Bechstein WO, Lohmann R, Radke C, Kling N, Wex C, Lobeck H, Hintze R. Extended resections for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1999;230(6):808–818. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199912000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, Tso WK, Lam CM, Wong J. Improved operative and survival outcomes of surgical treatment for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2006;93(12):1488–1494. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jong MC, Marques H, Clary BM, Bauer TW, Marsh JW, Ribero D, Majno P, Hatzaras I, Walters DM, Barbas AS, Mega R, Schulick RD, Choti MA, Geller DA, Barroso E, Mentha G, Capussotti L, Pawlik TM. The impact of portal vein resection on outcomes for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a multi-institutional analysis of 305 cases. Cancer. 2012;118:4737–4747. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemming AW, Reed AI, Fujita S, Foley DP, Howard RJ. Surgical management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2005;241(5):693–699. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000160701.38945.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribero D, Amisano M, Lo Tesoriere R, Rosso S, Ferrero A, Capussotti L. Additional resection of an intraoperative margin-positive proximal bile duct improves survival in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2011;254(5):776–781. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182368f85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito F, Cho CS, Rikkers LF, Weber SM. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Current management. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):210–218. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181afe0ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JH, Hwang DW, Lee SY, Park KM, Lee YJ. The proximal margin of resected hilar cholangiocarcinoma: the effect of microscopic positive margin on long-term survival. Am Surg. 2012;78(4):471–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seyama Y, Kubota K, Sano K, Noie T, Takayama T, Kosuge T, Makuuchi M. Long-term outcome of extended hemihepatectomy for hilar bile duct cancer with no mortality and high survival rate. Ann Surg. 2003;238(1):73–83. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000074960.55004.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otto G, Hoppe-Lotichius M, Bittinger F, Schuchmann M, Duber C. Klatskin tumour: Meticulous preoperative work-up and resection rate. Z Gastroenterol. 2011;49(4):436–442. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1246011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Endo I, House MG, Klimstra DS, Gonen M, D’Angelica M, Dematteo RP, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR. Clinical significance of intraoperative bile duct margin assessment for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(8):2104–2112. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebata T, Watanabe H, Ajioka Y, Oda K, Nimura Y. Pathological appraisal of lines of resection for bile duct carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2002;89(10):1260–1267. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakamoto E, Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, Kamiya J, Kondo S, Nagino M, Kanai M, Miyachi M, Uesaka K. The pattern of infiltration at the proximal border of hilar bile duct carcinoma: a histologic analysis of 62 resected cases. Ann Surg. 1998;227(3):405–411. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199803000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okazaki Y, Horimi T, Kotaka M, Morita S, Takasaki M. Study of the intrahepatic surgical margin of hilar bile duct carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49(45):625–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SG, Song GW, Hwang S, Ha TY, Moon DB, Jung DH, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Kim MH, Lee SK, Sung KB, Ko GY. Surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma in the new era: the Asan experience. JHepato-Biliary-Pancreat Surg. 2010;17(4):476–489. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kow AW, Wook CD, Song SC, Kim WS, Kim MJ, Park HJ, Heo JS, Choi SH. Role of caudate lobectomy in type III A and III B hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a 15-year experience in a tertiary institution. World J Surg. 2012;36(5):1112–1121. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1497-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Qin Y, Cui Y, Chen H, Hao X, Li Q. Analysis of the surgical outcome and prognostic factors for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a Chinese experience. Dig Surg. 2011;28(3):226–231. doi: 10.1159/000327361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bismuth H, Nakache R, Diamond T. Management strategies in resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1992;215(1):31–38. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199201000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shingu Y, Ebata T, Nishio H, Igami T, Shimoyama Y, Nagino M. Clinical value of additional resection of a margin-positive proximal bile duct in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery. 2010;147(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zervos EE, Pearson H, Durkin AJ, Thometz D, Rosemurgy P, Kelley S, Rosemurgy AS. In-continuity hepatic resection for advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2004;188(5):584–588. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evander A, Fredlund P, Hoevels J, Ihse I, Bengmark S. Evaluation of aggressive surgery for carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile ducts. Ann Surg. 1980;191(1):23–29. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198001000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Launois B, Campion JP, Brissot P, Gosselin M. Carcinoma of the hepatic hilus. Surgical management and the case for resection. Ann Surg. 1979;190(2):151–157. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197908000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fortner JG, Kallum BO, Kim DK. Surgical management of carcinoma of the junction of the main hepatic ducts. Ann Surg. 1976;184(1):68–73. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197607000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Longmire WP, McArthur MS, Bastounis EA, Hiatt J. Carcinoma of the extrahepatic biliary tract. Ann Surg. 1973;178(3):333–345. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197309000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beazley RM, Hadjis N, Benjamin IS, Blumgart LH. Clinicopathological aspects of high bile duct cancer. Experience with resection and bypass surgical treatments. Ann Surg. 1984;199(6):623–636. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198406000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blumgart LH, Hadjis NS, Benjamin IS, Beazley R. Surgical approaches to cholangiocarcinoma at confluence of hepatic ducts. Lancet. 1984;1(8368):66–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baer HU, Stain SC, Dennison AR, Eggers B, Blumgart LH. Improvements in survival by aggressive resections of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1993;217(1):20–27. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199301000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boerma EJ. Research into the results of resection of hilar bile duct cancer. Surgery. 1990;108(3):572–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hadjis NS, Blenkharn JI, Alexander N, Benjamin IS, Blumgart LH. Outcome of radical surgery in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery. 1990;107(6):597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramacciato G, Nigri G, Bellagamba R, Petrucciani N, Ravaioli M, Cescon M, Del Gaudio M, Ercolani G, Di Benedetto F, Cautero N, Quintini C, Cucchetti A, Lauro A, Miller C, Pinna AD. Univariate and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in the surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Am Surg. 2010;76(11):1260–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jarnagin WR, Bowne W, Klimstra DS, Ben-Porat L, Roggin K, Cymes K, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, D’Angelica M, Koea J, Blumgart LH. Papillary phenotype confers improved survival after resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2005;241(5):703–712. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000160817.94472.fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugiura Y, Nakamura S, Iida S, Hosoda Y, Ikeuchi S, Mori S, Sugioka A, Tsuzuki T. Extensive resection of the bile ducts combined with liver resection for cancer of the main hepatic duct junction: a cooperative study of the Keio Bile Duct Cancer Study Group. Surgery. 1994;115(4):445–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogura Y, Mizumoto R, Tabata M, Matsuda S, Kusuda T. Surgical treatment of carcinoma of the hepatic duct confluence: analysis of 55 resected carcinomas. World J Surg. 1993;17(1):85–92. doi: 10.1007/BF01655714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gazzaniga GM, Ciferri E, Bagarolo C, Filauro M, Bondanza G, Fazio S, Ermili F. Primitive hepatic hilum neoplasm. J Surg Oncol Suppl. 1993;3:140–146. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930530537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Makuuchi M, Thai BL, Takayasu K, Takayama T, Kosuge T, Gunven P, Yamazaki S, Hasegawa H, Ozaki H. Preoperative portal embolization to increase safety of major hepatectomy for hilar bile duct carcinoma: a preliminary report. Surgery. 1990;107(5):521–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neuhaus P, Thelen A. Radical surgery for right-sided klatskin tumor. HPB (Oxford) 2008;10(3):171–173. doi: 10.1080/13651820801992708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee SG, Lee YJ, Park KM, Hwang S, Min PC. One hundred and eleven liver resections for hilar bile duct cancer. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Surg. 2000;7(2):135–141. doi: 10.1007/s005340050167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyazaki M, Ito H, Nakagawa K, Ambiru S, Shimizu H, Okaya T, Shinmura K, Nakajima N. Parenchyma-preserving hepatectomy in the surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189(6):575–583. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(99)00219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Ardito F, Giovannini I, Aldrighetti L, Belli G, Bresadola F, Calise F, Dalla Valle R, D’Amico DF, Gennari L, Giulini SM, Guglielmi A, Jovine E, Pellicci R, Pernthaler H, Pinna AD, Puleo S, Torzilli G, Capussotti L, Cillo U, Ercolani G, Ferrucci M, Mastrangelo L, Portolani N, Pulitano C, Ribero D, Ruzzenente A, Scuderi V, Federico B. Improvement in perioperative and long-term outcome after surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Results of an Italian multicenter analysis of 440 patients. Arch Surg. 2012;147(1):26–34. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Gulik TM, Kloek JJ, Ruys AT, Busch OR, van Tienhoven GJ, Lameris JS, Rauws EA, Gouma DJ. Multidisciplinary management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Klatskin tumor): Extended resection is associated with improved survival. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rocha FG, Matsuo K, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. JHepato-Biliary-Pancreat Surg. 2010;17(4):490–496. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ikeyama T, Nagino M, Oda K, Ebata T, Nishio H, Nimura Y. Surgical approach to bismuth Type I and II hilar cholangiocarcinomas: Audit of 54 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2007;246(6):1052–1057. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318142d97e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dinant S, Gerhards MF, Rauws EA, Busch OR, Gouma DJ, van Gulik TM. Improved outcome of resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Klatskin tumor) Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(6):872–880. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gerhards MF, van Gulik TM, de Wit LT, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Evaluation of morbidity and mortality after resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma—a single center experience. Surgery. 2000;127(4):395–404. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.104250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paik KY, Choi DW, Chung JC, Kang KT, Kim SB. Improved survival following right trisectionectomy with caudate lobectomy without operative mortality: Surgical treatment for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(7):1268–1274. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0503-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cho MS, Kim SH, Park SW, Lim JH, Choi GH, Park JS, Chung JB, Kim KS. Surgical outcomes and predicting factors of curative resection in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma: 10-year single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1672–1679. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1960-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Young AL, Prasad KR, Toogood GJ, Lodge JPA. Surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma in a new era: Comparison among leading Eastern and Western centers, Leeds. J Hepato-Biliary-Panc Sci. 2009;17(4):497–504. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hirano S, Kondo S, Tanaka E, Shichinohe T, Tsuchikawa T, Kato K, Matsumoto J, Kawasaki R. Outcome of surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a special reference to postoperative morbidity and mortality. J Hepato-Biliary-Pan Sci. 2009;17(4):455–462. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Konstadoulakis MM, Roayaie S, Gomatos IP, Labow D, Fiel MI, Miller CM, Schwartz ME. Aggressive surgical resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: is it justified? Audit of a single center’s experience. Am J Surg. 2008;196(2):160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tan JW, Hu BS, Chu YJ, Tan YC, Ji X, Chen K, Ding XM, Zhang A, Chen F, Dong JH. One-stage resection for bismuth type IV hilar cholangiocarcinoma with high hilar resection and parenchyma-preserving strategies: a cohort study. World J Surg. 2013;37:614–621. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1878-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Song SC, Choi DW, Kow AW, Choi SH, Heo JS, Kim WS, Kim MJ. Surgical outcomes of 230 resected hilar cholangiocarcinoma in a single centre. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83(4):268–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Launois B, Terblanche J, Lakehal M, Catheline JM, Bardaxoglou E, Landen S, Campion JP, Sutherland F, Meunier B. Proximal bile duct cancer: High resectability rate and 5-year survival. Ann Surg. 1999;230(2):266–275. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199908000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Otani K, Chijiiwa K, Kai M, Ohuchida J, Nagano M, Kondo K. Role of hilar resection in the treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59(115):696–700. doi: 10.5754/hge09725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kawasaki S, Imamura H, Kobayashi A, Noike T, Miwa S, Miyagawa S. Results of surgical resection for patients with hilar bile duct cancer: Application of extended hepatectomy after biliary drainage and hemihepatic portal vein embolization. Ann Surg. 2003;238(1):84–92. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000074984.83031.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lim JH, Choi GH, Choi SH, Kim KS, Choi JS, Lee WJ. Liver resection for bismuth type I and type II hilar cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2013;37(4):829–837. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-1909-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen XP, Lau WY, Huang ZY, Zhang ZW, Chen YF, Zhang WG, Qiu FZ. Extent of liver resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2009;96(10):1167–1175. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mizumoto R, Kawarada Y, Suzuki H. Surgical treatment of hilar carcinoma of the bile duct. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1986;162(2):153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, Kamiya J, Kondo S, Shionoya S. Hepatic segmentectomy with caudate lobe resection for bile duct carcinoma of the hepatic hilus. World J Surg. 1990;14(4):535–543. doi: 10.1007/BF01658686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ercolani G, Zanello M, Grazi GL, Cescon M, Ravaioli M, Gaudio M, Vetrone G, Cucchetti A, Brandi G, Ramacciato G, Pinna AD. Changes in the surgical approach to hilar cholangiocarcinoma during an 18-year period in a Western single center. J Hepato-Biliary-Pan Sci. 2010;17(3):329–337. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng QB, Yi B, Wang JH, Jiang XQ, Luo XJ, Liu C, Ran RZ, Yan PN, Zhang BH. Resection with total caudate lobectomy confers survival benefit in hilar cholangiocarcinoma of Bismuth type III and IV. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38(12):1197–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dumitrascu T, Chirita D, Ionescu M, Popescu I. Resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Analysis of prognostic factors and the impact of systemic inflammation on long-term outcome. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:913–924. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kawarada Y, Das BC, Naganuma T, Tabata M, Taoka H. Surgical treatment of hilar bile duct carcinoma: experience with 25 consecutive hepatectomies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6(4):617–624. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(01)00008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jonas S, Benckert C, Thelen A, Lopez-Hanninen E, Rosch T, Neuhaus P. Radical surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34(3):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Witzigmann H, Berr F, Ringel U, Caca K, Uhlmann D, Schoppmeyer K, Tannapfel A, Wittekind C, Mossner J, Hauss J, Wiedmann M. Surgical and palliative management and outcome in 184 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Palliative photodynamic therapy plus stenting is comparable to r1/r2 resection. Ann Surg. 2006;244(2):230–239. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217639.10331.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rea DJ, Munoz-Juarez M, Farnell MB, Donohue JH, Que FG, Crownhart B, Larson D, Nagorney DM. Major hepatic resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Analysis of 46 patients. Arch Surg. 2004;139(5):514–523. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.5.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nagino M, Kamiya J, Arai T, Nishio H, Ebata T, Nimura Y. “Anatomic” right hepatic trisectionectomy (extended right hepatectomy) with caudate lobectomy for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2006;243(1):28–32. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000193604.72436.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shimada K, Sano T, Sakamoto Y, Kosuge T. Safety and effectiveness of left hepatic trisegmentectomy for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2005;29(6):723–727. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7704-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nishio H, Nagino M, Nimura Y. Surgical management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: the Nagoya experience. HPB (Oxford) 2005;7(4):259–262. doi: 10.1080/13651820500373010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ramesh H, Kuruvilla K, Venugopal A, Lekha V, Jacob G. Surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Feasibility and results of parenchyma-conserving liver resection. Dig Surg. 2004;21(2):114–122. doi: 10.1159/000077335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Farges O, Regimbeau JM, Fuks D, Le Treut YP, Cherqui D, Bachellier P, Mabrut JY, Adham M, Pruvot FR, Gigot JF. Multicentre European study of preoperative biliary drainage for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2013;100(2):274–283. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.van Gulik TM, van den Esschert JW, de Graaf W, van Lienden KP, Busch OR, Heger M, van Delden OM, Lameris JS, Gouma DJ. Controversies in the use of portal vein embolization. Dig Surg. 2008;25(6):436–444. doi: 10.1159/000184735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hasegawa S, Ikai I, Fujii H, Hatano E, Shimahara Y. Surgical resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Analysis of survival and postoperative complications. World J Surg. 2007;31(6):1256–1263. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9001-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nagino M, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Igami T, Sugawara G, Takahashi Y, Nimura Y. Evolution of surgical treatment for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: a single-center 34-year review of 574 consecutive resections. Ann Surg. 2012;258(1):129–140. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182708b57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shimada H, Endo I, Sugita M, Masunari H, Fujii Y, Tanaka K, Sekido H, Togo S. Is parenchyma-preserving hepatectomy a noble option in the surgical treatment for high-risk patients with hilar bile duct cancer? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2003;388(1):33–41. doi: 10.1007/s00423-003-0358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.van Gulik TM, Ruys AT, Busch OR, Rauws EA, Gouma DJ. Extent of liver resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma (klatskin tumor): how much is enough? Dig Surg. 2011;28(2):141–147. doi: 10.1159/000323825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Endo I, Matsuyama R, Mori R, Taniguchi K, Kumamoto T, Takeda K, Tanaka K, Kohn A, Schenk A (2014) Imaging and surgical planning for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci [DOI] [PubMed]

- 83.Sasaki R, Kondo T, Oda T, Murata S, Wakabayashi G, Ohkohchi N. Impact of three-dimensional analysis of multidetector row computed tomography cholangioportography in operative planning for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2011;202(4):441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nagino M. Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: a surgeon’s viewpoint on current topics. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47(11):1165–1176. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0628-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kobayashi A, Miwa S, Nakata T, Miyagawa S. Disease recurrence patterns after R0 resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2010;97(1):56–64. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Witzigmann H, Wiedmann M, Wittekind C, Mossner J, Hauss J. Therapeutical concepts and results for Klatskin tumors. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105(9):156–161. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Uesaka K. Left hepatectomy or left trisectionectomy with resection of the caudate lobe and extrahepatic bile duct for hilar cholangiocarcinoma (with video) J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Surg. 2012;19(3):195–202. doi: 10.1007/s00534-011-0474-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shimizu H, Kimura F, Yoshidome H, Ohtsuka M, Kato A, Yoshitomi H, Furukawa K, Miyazaki M. Aggressive surgical resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma of the left-side predominance: radicality and safety of left-sided hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 2010;251(2):281–286. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181be0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Endo I, Matsuyama R, Taniguchi K, Sugita M, Takeda K, Tanaka K, Shimada H. Right hepatectomy with resection of caudate lobe and extrahepatic bile duct for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Surg. 2012;19(3):216–224. doi: 10.1007/s00534-011-0481-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kondo S, Hirano S, Ambo Y, Tanaka E, Okushiba S, Morikawa T, Katoh H. Forty consecutive resections of hilar cholangiocarcinoma with no postoperative mortality and no positive ductal margins: Results of a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2004;240(1):95–101. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000129491.43855.6b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Neuhaus P, Thelen A, Jonas S, Puhl G, Denecke T, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Seehofer D. Oncological superiority of hilar en bloc resection for the treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;19(5):1602–1608. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Miyazaki M, Kato A, Ito H, Kimura F, Shimizu H, Ohtsuka M, Yoshidome H, Yoshitomi H, Furukawa K, Nozawa S. Combined vascular resection in operative resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: does it work or not? Surgery. 2007;141(5):581–588. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hemming AW, Mekeel K, Khanna A, Baquerizo A, Kim RD. Portal vein resection in management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(4):604–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Miyazaki M, Kimura F, Shimizu H, Yoshidome H, Ohtsuka M, Kato A, Yoshitomi H, Nozawa S, Furukawa K, Mitsuhashi N, Takeuchi D, Suda K, Yoshioka I. Recent advance in the treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Hepatectomy with vascular resection. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Surg. 2007;14(5):463–468. doi: 10.1007/s00534-006-1195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Abbas S, Sandroussi C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the role of vascular resection in the treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2013;15(7):492–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen W, Ke K, Chen YL. Combined portal vein resection in the treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(5):489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.02.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wu XS, Dong P, Gu J, Li ML, Wu WG, Lu JH, Mu JS, Ding QC, Zhang L, Ding Q, Weng H, Liu YB. Combined portal vein resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17(6):1107–1115. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tamoto E, Hirano S, Tsuchikawa T, Tanaka E, Miyamoto M, Matsumoto J, Kato K, Shichinohe T. Portal vein resection using the no-touch technique with a hepatectomy for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2014;16:56–61. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nagino M, Nimura Y, Nishio H, Ebata T, Igami T, Matsushita M, Nishikimi N, Kamei Y. Hepatectomy with simultaneous resection of the portal vein and hepatic artery for advanced perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: an audit of 50 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2010;252(1):115–123. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e463a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ebata T, Nagino M, Kamiya J, Uesaka K, Nagasaka T, Nimura Y. Hepatectomy with portal vein resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Audit of 52 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2003;238(5):720–727. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094437.68038.a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hirano S, Kondo S, Tanaka E, Shichinohe T, Tsuchikawa T, Kato K. No-touch resection of hilar malignancies with right hepatectomy and routine portal reconstruction. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Surg. 2009;16(4):502–507. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]