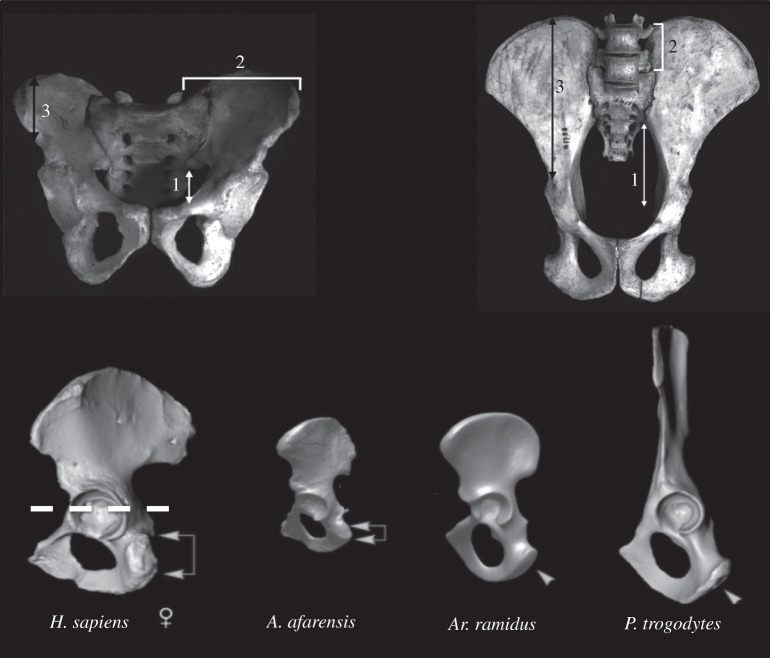

Figure 1.

The pelvis in (L to R) modern human (Homo sapiens), early hominins and chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes). In the anterior view (upper), note shortening of the height of the body (1) and blade (3) of the ilium in Homo compared with Pan, which lowers the centre of mass in the former. The iliac blade is also more laterally placed and the sacrum is wider in humans (2), which eliminates the entrapment of the lower lumbar vertebrae seen in the chimpanzee (2). In the lateral view (lower), note especially the coronal orientation of the iliac blade in the chimpanzee compared with the more laterally rotated blade in the hominins, which allows gluteal muscles that arise from the external surface of the ilium and attach to the greater trochanter of the femur to act as abductors of the thigh and, when the lower limb is in stance phase, to counteract tipping of the pelvis. In addition note the length of the ischium in Homo compared with Pan. Like chimpanzees, the ischium in Ar. ramidus is relatively long, indicating a potential mosaic evolution of the pelvis in early hominin evolution. The ischium is the site of attachment for hamstrings and sacrotuberous ligament; the small triangles indicate the orientation of the ischial tuberosity, which is directed inferiorly in Ar. ramidus and the chimpanzee but more posteriorly in A. afarensis and modern humans. (Adapted from references [20,21].)