Abstract

Objective

To compare baseline characteristics, treatment frequency, visual acuity (VA), and morphologic outcomes of eyes with > 50% of the lesion composed of blood (B50 group) versus all other eyes (Other group) enrolled in the Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD) Treatments Trials (CATT).

Design

Prospective cohort study within a multicenter randomized clinical trial.

Participants

CATT patients with neovascular AMD.

Methods

Treatment for the study eye was assigned randomly to either ranibizumab or bevacizumab and to three different regimens for dosing over a two-year period. Reading center graders evaluated baseline and follow-up morphology in color fundus photographs (CFP), fluorescein angiograms (FA), and optical coherence tomography (OCT). Masked examiners tested VA.

Main Outcome Measures

VA and morphologic features at 1 and 2 years.

Results

The B50 group consisted of 84 (7.1%) of 1185 patients enrolled in CATT. The baseline lesion characteristics of the B50 group differed from the Other group. In the B50 group, CNV size was smaller (0.73 vs 1.83 Disc Areas (DA); p <0.001), total lesion size was greater (4.55 vs 2.31 DA; p <0.001), total retinal thickness was greater (524 vs 455 um; p=0.02), and mean VA was worse (56.0 vs. 60.9 letters, p=0.002). Increases in mean VA were similar in the B50 and Other groups at 1 year (+9.3 vs. +7.2 letters, p=0.22) and at 2 years (9.0 vs. 6.1 letters, p=0.17). Eyes treated PRN received a similar number of injections in the two groups (12.2 vs 13.4, p=0.27). Mean lesion size in the B50 group decreased by 1.2 DA at both 1 and 2 years (primarily due to resolution of hemorrhage) and increased in the Other group by 0.33 DA at 1 year and 0.91 DA at 2 years (p<0.001). Leakage on FA and fluid on OCT were similar between groups at 1 and 2 years.

Conclusion

In CATT, the B50 group had a visual prognosis similar to the Other group. Lesion size decreased markedly through 2 years. Eyes like those enrolled in CATT with neovascular AMD lesions composed of >50% blood can be managed similarly to those with less or no blood.

The most dramatic presentation of exudative macular degeneration is the sudden onset of subretinal hemorrhage accompanying the development of choroidal neovascularization. The natural history of such lesions is variable.1–3 Large hemorrhages are associated with damage or atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and thus removal with subretinal surgery or pneumatic displacement has been advocated in the past.4,5 Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) intravitreal injection has also been used as a sole agent or in combination with pneumatic displacement to facilitate resorption of hemorrhage and prevention of fibrosis formation.6,7

Eyes with large subretinal hemorrhage have been excluded from every major therapeutic trial of thermal laser, photodynamic therapy, and agents targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).8–12 Eligibility criteria for the initial clinical trials for choroidal neovascularization required that less than 50% of the lesion area be composed of hemorrhage because of the need to target the area of neovascularization for thermal laser and additional concerns about the ability to activate verteporfin in the presence of blood for photodynamic therapy. These exclusion criteria were carried forward to the early phase and registration trials of anti-VEGF agents because of their historical use and because of concerns about the efficacy of pegaptanib, ranibizumab, and aflibercept in the presence of blood. These exclusions have led to a dearth of information regarding the potential for such eyes to respond to treatments, with only a few case series having a small number of patients or short follow-up period providing information on outcomes of anti-VEGF treatment.13–17 The Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD) Treatments Trials (CATT) chose to include eyes with lesions composed of greater than 50% hemorrhage in an effort to understand their response to anti-VEGF therapy and to further guide clinicians in the care of such challenging eyes.

METHODS

Study Population for the Clinical Trial

Details of the design and methods for CATT have been published previously.18–21 Patients enrolled through 43 clinical centers in the United States between February 2008 and December 2009. Inclusion criteria included age ≥ 50 years, presence in the study eye (one eye per patient) of previously untreated, active choroidal neovascularization (CNV) secondary to AMD, and visual acuity (VA) between 20/25 and 20/320 in the study eye. Active CNV was considered present when both leakage on fluorescein angiography and fluid on time-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) were documented through central review of images. Fluid on OCT could be within or beneath the retina or beneath the RPE. Either neovascularization, fluid, pigment epithelial detachment, blocked fluorescence, or hemorrhage needed to be under the fovea. Hemorrhage associated with the lesion could be superficial, sub-retinal or sub-RPE in location. Hemorrhage was considered to be part of the lesion only when it was contiguous with the total neovascular lesion and the hemorrhage extended beyond the fluorescence of the underlying CNV on fluorescein angiography. During the trial, eligibility criteria were modified to allow lesions composed of > 50% blood in order to study this population specifically. Prior to 10/13/2008, study eyes that had neovascular lesions with >50% hemorrhage as part of the lesion were considered ineligible and were excluded from recruitment. The exception to the >50% blood rule was retinal angiomatous proliferations (RAP) where the area of superficial hemorrhage associated with the lesion was often more than 50%. When blood was one of the lesion components, the area of the lesion was classified as <50% blood, or ≥ 50% blood. The study was approved by an institutional review board associated with each center, was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00593450). All patients provided written informed consent.

Treatment Assignment of the Study Eye

At enrollment, patients were assigned with equal probability to one of four treatment groups defined by drug (ranibizumab or bevacizumab) and by dosing regimen (monthly or pro re nata (PRN)). At one year, patients initially assigned to monthly treatment retained their drug assignment but were re-assigned randomly, with equal probability, to either monthly or PRN treatment. Patients initially assigned to PRN treatment had no change in assignment; i.e., they retained both their drug assignment and PRN dosing regimen for year 2.

Study Procedures

At enrollment, patients provided a medical history, had VA testing, and had bilateral color stereoscopic fundus photography, fluorescein angiography and time domain optical coherence tomography (OCT). Follow-up examinations were scheduled every 28 days for two years. Eyes assigned to monthly treatment received an injection at every follow-up examination. Eyes assigned to PRN treatment had OCT scans at every examination and were treated if there was fluid by OCT or other signs of active neovascularization. Masked VA acuity examiners tested VA at selected visits, including 52 and 104 weeks. Color fundus photography and fluorescein angiography were performed at 52 and 104 weeks. Masked graders at the Photograph Reading Center assessed color photographs and fluorescein angiograms for features of the neovascular lesion and of AMD.20 The total neovascular lesion could be composed of CNV and/or scar, serous pigment epithelial detachment, blocked fluorescence and hemorrhage. For grading of hemorrhage as a lesion component at baseline, the hemorrhage had to extend beyond the fluorescence of the underlying CNV on fluorescein angiography. However, in the follow up visits hemorrhage situated anywhere in the area of the baseline total CNV lesion or in adjacent areas was graded as part of the total CNV lesion irrespective of the presence of active neovascularization.

Masked graders at the CATT OCT Reading Center identified intraretinal fluid (IRF), subretinal fluid (SRF), and fluid below the retinal pigment epithelium (sub-RPE) and measured the thickness at the foveal center of the retina, subretinal fluid, and subretinal tissue complex.21

Statistical Analyses

Eyes with lesions composed of ≥ 50% blood comprised a group, the B50 group that was compared to the group of all other study eyes, the Other group. Characteristics measured on a categorical scale were compared between groups by chi-square tests. Those measured on a continuous scale were compared with independent t-tests. Analyses involving the assigned drug or dosing regimen at year 2 included only those patients who completed at least one visit at a CATT clinical center between week 52 and 104, inclusive. Linear (continuous outcome measures) and logistic (dichotomous outcome measures) regression models including interaction terms were used to assess whether the effect of having ≥ 50% blood at baseline differed by drug or dosing regimen. Statistical computations were performed with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Eighty-four (7.1%) of 1185 patients enrolled in CATT had neovascular lesions with more than 50% of the lesion area composed of blood (B50 group). The baseline demographic characteristics were similar between the B50 group and the eyes with no or less blood (Other group) (Table 1). The mean age of both groups was 79.3 years. Approximately 60% of each group was female. The B50 group had a lower proportion of former or current smokers (46.4% vs 58.0%, p = 0.04). The rates of hypertension and of use of anticoagulant medication were similar between the two groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of groups based on presence of ≥ 50% hemorrhage (N=1185)

| Baseline Characteristics | With ≥50% hemorrhage (N=84) | Without ≥50% hemorrhage (N=1101) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | |||

| Age, years: Mean (SD) | 79.3 (7.49) | 79.3 (7.53) | 0.94 |

| Female (n, %) | 49 (58.3) | 683 (62.0) | 0.56 |

| Former or current cigarette smoker (n, %) | 39 (46.4) | 638 (58.0) | 0.04 |

| Presence of hypertension (n, %) | 57 (67.9) | 766 (69.6) | 0.81 |

| With anticoagulant use (n, %)) | 45 (53.6) | 577 (52.4) | 0.91 |

| Taking AREDS supplement (n, %) | 59 (70.2) | 687 (62.4) | 0.16 |

| GA in fellow eye (n, %) | 13 (15.5) | 130 (11.8) | 0.39 |

| CNV in fellow eye (n, %) | 34 (40.5) | 315 (28.6) | 0.02 |

| Study eye | |||

| Visual acuity, letters: Mean (SD) | 56.0 (13.4) | 60.9 (13.5) | 0.002 |

| Area of choroidal neovascularization, disc areas: Mean (SD) | 0.73 (0.81) | 1.83 (1.79) | <0.001 |

| Baseline total area of lesion, disc areas: Mean (SD) | 4.55 (4.72) | 2.31 (2.20) | <0.001 |

| Presence of occult lesion (n, %) | 43 (51.2) | 653 (59.3) | 0.20 |

| Presence of RAP lesion (n, %) | 5 ( 6.0) | 123 (11.2) | 0.15 |

| Total foveal thickness, microns: Mean (SD) | 524 (194) | 455 (185) | 0.001 |

From independent t-test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

SD = standard deviation

At baseline, mean VA was worse in the B50 group (56.0 [≈20/80] vs. 60.9 [≈20/63] letters, p=0.002). Lesion characteristics differed markedly between groups. In the B50 group, CNV size was smaller (0.73 vs 1.83 Disc Areas (DA); p <0.0001) but total lesion size was greater (4.55 vs 2.31 DA; p <0.0001). The two groups had similar rates of occult CNV (51.2% and 59.3%; p=0.20) and retinal angiomatous proliferation (6.0% vs 11.2%, p = 0.15). Eyes in the B50 group were more likely to have a fellow eye with concurrent CNV than the Other group (40.5% vs 28.6%, p=0.02). Total retinal thickness was greater in the B50 group (524 vs 455 um; p=0.001). By definition, every eye in the B50 group had hemorrhage as a component of the lesion (at least 50% of the total lesion area), while 30.6% (337 eyes) of the Other group had hemorrhage contiguous with the lesion. Hemorrhage was subfoveal in 50 (59.5%) eyes in the B50 group and in 43 (3.9%) of the Other group.

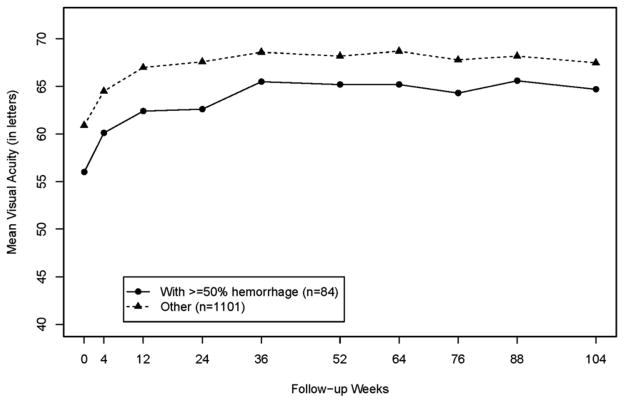

Outcomes during follow-up

The outcomes of mean VA, mean change in VA from baseline, and proportion of eyes increasing ≥15 letters were similar between the B50 and Other group at 1 year (Table 2) and 2 years (Table 3). The pattern of increase in mean VA over time in the B50 group was approximately parallel to the pattern in the Other group (Figure 1), with improving mean VA through 36 weeks and then a plateau through 104 weeks. Increases from baseline in mean VA letter score at 1 year were +9.3 in the B50 group vs. +7.1 in the Other group (p=0.22) and at 2 years were +9.0 vs. +6.1 respectively (p= 0.17). The proportion of eyes achieving at least three lines of improvement (15 letters) in VA at 2 years was 33.3% in the B50 group vs 29.4% in the Other group (p=0.50). The associations between VA during follow-up and the presence of ≥ 50% hemorrhage at baseline did not differ by whether ranibizumab or bevacizumab was used for treatment or by the dosing regimen (p> 0.10).

Table 2.

Year 1 outcomes of groups based on presence of ≥ 50% hemorrhage at baseline (N=1106§)

| Year 1 Outcomes | With ≥50% hemorrhage (N=78) | Without ≥50% hemorrhage (N=1028) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual acuity, letters: Mean (SE) | 65.2 (2.1) | 68.2 (0.6) | 0.15 |

| Visual acuity, Snellen (letters) | |||

| 20/15 – 20/40 (letter range ) | 45(57.7) | 671(65.3) | |

| 20/50–20/160 (letter range ) | 26(33.3) | 288(28.0) | |

| 20/200 or worse (letter range ) | 7(9.0) | 69( 6.7) | |

| Visual acuity change from baseline, letters: | |||

| ≥ 15 letters decrease (n, %) | 6(7.7) | 62( 6.0) | |

| < 15 letters changed (n,%) | 47(60.3) | 664(64.6) | |

| ≥ 15 letters increase (n, %) | 25 (32.1) | 302 (29.4) | |

| Visual acuity change from baseline, letters: Mean (SE) | 9.3 (1.7) | 7.2 (0.5) | 0.22 |

| Hemorrhage contiguous with lesion (n, %) | 3 (3.9) | 18 ( 1.8) | 0.19 |

| Retinal thickness at fovea, microns | 0.02 | ||

| <120 (n, %) | 18 (23.4) | 218 (21.5) | |

| 120–212 (n, %) | 43 (55.8) | 691 (68.3) | |

| >212 (n, %) | 16 (20.8) | 103 (10.2) | |

| Change in total foveal thickness from baseline, microns: Mean (SE) | −199 (20.5) | −168 ( 5.7) | 0.15 |

| No fluid on OCT (n, %) | 20 (26.0) | 293 (29.5) | 0.60 |

| Leakage on FA (n, %) | 33 (43.4) | 446 (46.1) | 0.72 |

| Change in lesion size from baseline, disc areas: Mean (SE) | −1.2 (0.42) | 0.33 (0.07) | <0.001 |

| Pathology in fovea center | 0.008 | ||

| No pathology (n, %) | 15 (19.2) | 198 (19.3) | |

| Fluid only (n, %) | 3 (3.9) | 83 ( 8.1) | |

| Choroidal neovascularization (n, %) | 13 (16.7) | 246 (24.0) | |

| Scar (n, %) | 23 (29.5) | 179 (17.4) | 0.01 |

| Geographic atrophy (n, %) | 2 (2.6) | 20 ( 2.0) | |

| Non-geographic atrophy (n, %) | 12 (15.4) | 139 (13.5) | |

| Hemorrhage (n, %) | 2 (2.6) | 1 ( 0.1) | |

| RPE tear (n, %) | 1 (1.3) | 9 ( 0.9) | |

| Other(n, %) | 7 (9.0) | 153 (14.9) | |

| RPE tear involving macula, (n,%) | 5 (6.4) | 13 ( 1.3) | 0.007 |

| Mean number of injections, PRN† only: Mean (SE) | 7.2 (0.5) | 7.3 (0.1) | 0.94 |

Number of patients with Year 1 visual acuity outcome.

From independent t-test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

42 patients with ≥50% hemorrhage and 514 patients without ≥50% hemorrhage were in PRN groups.

SE = standard error

RPE = retinal pigment epithelium

Table 3.

Year 2 outcomes of groups based on presence of ≥ 50% hemorrhage at baseline (N=1034§)

| Year 2 Outcomes | With ≥50% hemorrhage (N=72) | Without ≥50% hemorrhage (N=962) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual acuity, letters: Mean (SE) | 64.7 (2.2) | 67.5 (0.6) | 0.22 |

| Visual acuity, Snellen (letters) | |||

| 20/15 – 20/40 (letter range ) | 40(55.6) | 614(63.8) | |

| 20/50–20/160 (letter range ) | 26(36.1) | 276(28.7) | |

| 20/200 or worse (letter range ) | 6( 8.3) | 72( 7.5) | |

| Visual acuity change from baseline, letters: | |||

| ≥ 15 letters decrease (n, %) | 2( 2.8) | 93( 9. 7) | |

| < 15 letters changed (n,%) | 46(63.9) | 586(60.9) | |

| ≥ 15 letters increase (n, %) | 24 (33.3) | 283 (29.4) | |

| Visual acuity change from baseline, letters: Mean (SE) | 9.0 (1.9) | 6.1 (0.5) | 0.17 |

| Hemorrhage contiguous with lesion (n, %) | 2 ( 2.9) | 28 ( 3.0) | 1.00 |

| Retinal thickness at fovea, microns | 0.13 | ||

| <120 (n, %) | 14 (20.6) | 232 (24.4) | |

| 120–212 (n, %) | 40 (58.8) | 603 (63.5) | |

| >212 (n, %) | 14 (20.6) | 114 (12.0) | |

| Change in total foveal thickness from baseline, microns: Mean (SE) | −206 (23.6) | −161 ( 6.2) | 0.06 |

| No fluid on OCT (n, %) | 18 (26.5) | 223 (23.8) | 0.66 |

| Leakage on FA (n, %) | 17 (25.0) | 263 (28.5) | 0.58 |

| Change in lesion size from baseline, disc areas: Mean (SE) | −1.2 (0.46) | 0.91 (0.08) | <0.001 |

| Pathology in fovea center | 0.03 | ||

| No pathology (n, %) | 17 (23.6) | 187 (19.4) | |

| Fluid only (n, %) | 0 ( 0.0) | 33 (3.43) | |

| Choroidal neovascularization (n, %) | 9 (12.5) | 168 (17.5) | |

| Scar (n, %) | 27 (37.5) | 202 (21.0) | 0.002 |

| Geographic atrophy (n, %) | 3 ( 4.2) | 60 ( 6.24) | |

| Non-geographic atrophy (n, %) | 7 ( 9.7) | 182 (18.9) | |

| Hemorrhage (n, %) | 1 (1.4) | 6 ( 0.6) | |

| RPE tear (n, %) | 0 (0.0) | 9 ( 0.9) | |

| Other(n, %) | 8 (11.1) | 115 (12.0) | |

| RPE tear involving macula, (n,%) | 2 ( 2.9) | 14 ( 1.5) | 0.30 |

| Mean number of injections, PRN† only: Mean (SE) | 12.2 (1.1) | 13.4 (0.3) | 0.27 |

Number of patients with Year 2 visual acuity outcome.

From independent t-test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

39 patients with ≥50% hemorrhage and 476 patients without ≥50% hemorrhage were in PRN groups.

SE = standard error

RPE = retinal pigment epithelium

Figure 1.

Mean visual acuity (VA) by presence of ≥ 50% hemorrhage at baseline

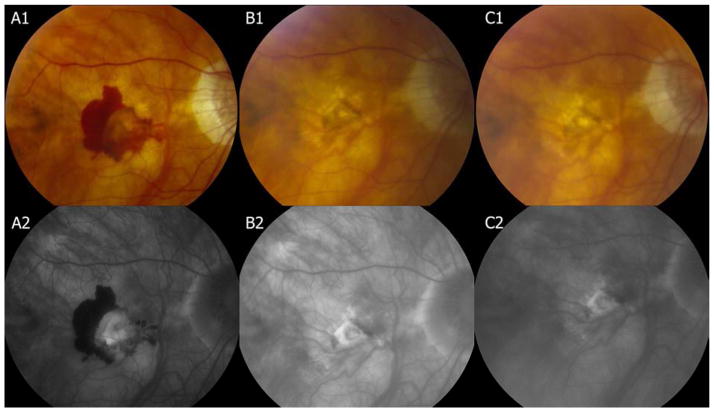

Assessment of macular morphology was conducted to identify central macular changes that could influence visual outcome (Figure 2). At both 1 and 2 years, few (<5%) eyes had contiguous blood in either group (Tables 2 and 3). Recurrent hemorrhage in the B50 group was uncommon, with 3 eyes developing new hemorrhage between Year 1 and 2. Mean total foveal thickness decreased in the B50 group at 1 year by 199 um and by 168 um in the Other group (p=0.15) with little additional change at 2 years. Lesion activity as indicated by fluid on OCT and by leakage on fluorescein angiography was similar between both groups at both 1 and 2 years. Mean lesion size in the B50 group decreased by 1.2 DA at 1 year and at 2 years but increased in the Other group by 0.33 DA at 1 year and 0.91 DA at 2 years (p<0.001). The B50 group had more foveal scarring at 1 year (29.5% vs 17.4%, p = 0.01) and at 2 years (37.5% vs 21.0%; p=0.002). Scarring in the foveal center was not restricted in either group to eyes that had blood at the fovea at baseline. Although more eyes in the B50 group were found to have a greater cumulative incidence of RPE tears in the macular region over two years (5 [6.4%] of 78 vs 13 [1.3%] of 1028) of the Other group, p=0.007), the presence of RPE tears involving the center of the macula was equal and uncommon (≈1%) in the two groups. Analysis of baseline factors predictive of outcome was similar for the B50 group as that previously reported for the group as a whole.38(Table 4 available at http://aaojournal.org) Factors in the study eye associated with worse visual acuity at 1 year were worse baseline visual acuity and larger CNV area. In the full study population, increased retinal thickness was adversely related to visual outcome38. Among patients assigned to PRN treatment for 2 years, B50 and Other groups had a similar number of treatments (12.2 and 13.4, respectively; p=0.27).

Figure 2.

At baseline, hemorrhage is greater than 50% of the lesion and visual acuity is 55 letters (≈20/80). At Year 1, hemorrhage has resolved and visual acuity has improved to 69 letters (≈20/40). At Year 2, the lesion size is stable and visual acuity has decreased 3 letters.

Table 4.

Multivariate linear regression* analysis for factors associated with visual acuity score (letters) at Year 1 among eyes with hemorrhage > 50% at baseline (N=78 with Year 1 visual acuity)

| Factor | Subjects | Mean Visual Acuity Score (Standard Error) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline visual acuity (per letter decrease) | 78 | −0.76 (0.12) | <0.0001 |

| Baseline area of choroidal neovascularization, disc areas | |||

| <=1 | 38 | 69.8 (2.33) | 0.03 |

| >1 | 12 | 61.7 (4.19) | |

| Unknown | 28 | 60.7 (2.78) | |

| Taking AREDS supplements | |||

| No | 24 | 60.1 (29.3) | 0.04 |

| Yes | 54 | 67.5 (1.95) | |

| Treatment Group | |||

| Ranibizumab monthly | 20 | 63.8 (3.22) | 0.87 |

| Bevacizumab monthly | 16 | 67.8 (3.59) | |

| Ranibizumab as needed | 21 | 65.0 (3.14) | |

| Bevacizumab as needed | 21 | 65.3 (3.11) |

The full, initial model included baseline visual acuity, baseline area of choroidal neovascularization, taking AREDS supplements, occult neovascularization, smoking status, total retinal thickness, treatment group.

DISCUSSION

Subretinal hemorrhage associated with exudative age-related macular degeneration may be associated with severe vision loss, fibrous scarring, and RPE atrophy.3 A study of 41 eyes with subfoveal hemorrhage that comprised more than 50% of the neovascular lesion found a mean loss of 3.5 (≈18 letters) lines at 3 year follow up, with 44% losing more than 6 lines (≈30 letters).2 Experimental models have demonstrated mechanical shearing of the outer segments from fibrin adhesions, apoptosis and retinal toxicity induced by migration of iron into photoreceptors and the retinal pigment epithelium as mechanisms of retinal damage caused by the presence of subretinal hemorrhage.22–24 Treatment for AMD lesions with significant subretinal hemorrhage has included management directed toward elimination or displacement of the hemorrhage. This has ranged from intravitreal injection of tissue plasminogen activator to allow fibrinolysis and absorption of the hemorrhage to subretinal injection of tPA during a vitrectomy with subsequent pneumatic displacement.7, 25–28 The Submacular Surgery Trial incorporated removal of the entire CNV complex along with the subretinal hemorrhage. In the group with more than 50% of the lesion consisting of hemorrhage there was no benefit on vision from surgery. The group included many eyes with worse baseline VA and larger hemorrhagic lesions than the CATT trial and the results are not directly comparable. However the poor outcome and high rate of complications, with 16% of the treatment group developing retinal detachment versus 2% of the observation group, served as an impetus to study eyes with larger amounts of hemorrhage in the CATT trial.4

Despite the benefits on vision of anti-VEGF treatment in previous clinical trials, the results of those trials cannot be extrapolated to eyes with larger amounts of subretinal hemorrhage. The CATT trial compared bevacizumab and ranibizumab in 3 different dosing regimens over a period of two years and enrolled 84 eyes with exudative AMD where more than 50% of the lesion area at baseline consisted of hemorrhage (B50 group). This affords the first opportunity to compare the outcome of such AMD lesions with the majority of eyes treated in the trial that had less associated hemorrhage (Other group).

The demographics of the two groups were very similar. The groups were compared for risk factors previously associated with presence and severity of subretinal hemorrhage, particularly hypertension and use of anticoagulant therapy. In a retrospective study of 71 consecutive patients with subretinal hemorrhage, use of anticoagulants was associated with a hemorrhage area of 9.71 DA versus 2.99 DA in those not using such medicines.29 Another study found a relative risk of 11.6 for developing large hemorrhage with the use of anticoagulants in the setting of exudative AMD. They did not find an increase in risk with the use of anti-platelet agents.30 In the CATT trial, use of anticoagulant medication was comparable between the two groups (53.6% B50 vs 52.4% Other). The proportion with hypertension was also very similar (66.7% vs 69.2%).

The most important differences between groups at baseline were visual acuity and lesion size. The B50 group started with a mean VA of 56.0 letters versus the Other group that had a mean of 60.9 letters. The worse acuity was associated with a mean total lesion area of 4.55 DA versus 2.31 DA for the Other group. Considering the significantly smaller area of visible CNV in the B50 group, the majority of B50 lesions were composed of blood. Both groups had resolution of blood over the course of the first year, with < 5% retaining blood as a lesion component at Year 1. Recurrence of hemorrhage was uncommon in the B50 group, with only 3 eyes demonstrating this at Year 2. Resolution of blood resulted in significant reduction in the overall size of the exudative lesion at Year 1 in the B50 group. The total lesion size in the B50 group decreased by 1.2 DA, versus an increase of 0.91 DA for the Other group at Year 2. The marked difference between the B50 and Other group in the changes in lesion size during follow-up was similar among the 3 treatment regimens (PRN, monthly, or monthly followed by PRN) and 2 drugs (ranibizumab or bevacizumab).

The presence of a larger amount of hemorrhage at baseline was associated with development of fibrotic scar at the center of the macula in follow-up. At Year 1, the B50 group had foveal scarring/fibrosis in 29.5% of eyes while the Other group had 17.4%. At Year 2, this increased to 38.6% vs 21% respectively. This is more favorable than the 53.3% combined fibrosis and atrophic scar reported in a natural history study of 60 eyes with subretinal hemorrhage.3 In the CATT trial, center-involving scarring occurred with nearly equal frequency in eyes that had blood located outside the macular center at baseline as it did in eyes with blood at the center. The development of subretinal fibrosis can occur with regression of choroidal neovascularization in the absence of subretinal hemorrhage.31

The presence of large subretinal hemorrhage with AMD has been associated with a high incidence of RPE tears.30,32 As well, RPE tears have been described as a potential consequence of anti-VEGF injection, particularly in the setting of large serous PED.33–37 At baseline, 2.5% of the Other group had serous PED involving the center versus no eyes in the B50 group. In follow-up, the B50 group was more likely to have an RPE tear in the macular region (6.4%) than the Other group (1.3%), but much less frequently than the 35% reported in association with large hemorrhages in a retrospective study. Importantly, RPE tears in the macular center were equally uncommon in both groups and therefore unlikely to significantly affect the overall visual outcome in the CATT patient groups.

Retinal thickness as measured by OCT was greater in the B50 group (524 um) than the Other group (455 um) at baseline. Greater retinal thickness at baseline has been associated with worse visual acuity outcome at Year 1 in the CATT population overall.38 There was a marked decrease in retinal thickness over the first year in both groups (−199 um and −168 um). The OCT findings are similar to those described in a small prospective study of ranibizumab treatment for eyes with lesions similar to the B50 group. In this small study, seven eyes were treated for one year and had a mean reduction in thickness of 120 um.13 In CATT, there was minimal further change in retinal thickness over the second year. Both groups had gradual and equal reduction of leakage on fluorescein angiography over two years, indicating further regression of the CNV lesion.

The pattern of visual acuity improvement was similar in the B50 and Other groups (Figure 1). The VA results are consistent with previously reported findings from CATT that eyes with worse baseline VA do not achieve the same level of VA as eyes with better VA at baseline.38 Despite the finding of fibrosis at the fovea in 37.5% of eyes in the B50 group at Year 2, the VA improved by 9.3 letters at Year 1 and 9.4 letters at Year 2. The rate of improvement mirrored the group with no blood or less than 50% blood, that gained 7.2 letters at Year 1 and 6.1 letters at Year 2. The rate of three line improvement (33.3% of B50) was also similar among the two groups. Analysis of subgroups supported the finding that VA gains were similar for the B50 group and the Other group whether eyes were treated with ranibizumab or bevacizumab and whether treatment was delivered monthly or PRN. This is consistent with the overall conclusions of the CATT trial but increases the generalizability of the findings. Eyes with exudative AMD with greater than 50% of the lesion composed of blood responded just as well as those with less or no blood.

The results described for the B50 group will not be applicable for all AMD lesions with large subretinal hemorrhages. The thickness of the hemorrhage, a factor that may affect prognosis, was not measured in CATT.39 The CATT trial inclusion criteria set a minimum corrected VA of 20/320. Although the size of some lesions was very large (up to 10 DA and 800 um total retinal thickness), there are subretinal hemorrhages that are significantly larger that may benefit from surgical interventions such as pneumatic displacement or subretinal evacuation with vitrectomy and gas placement.7, 25–28 The CATT results have shown that treatment with anti-VEGF injections alone may be preferable as the VA outcome was better than reported in most surgical case series and had a much lower complication rate. In addition, previous case series including eyes with substantially worse baseline visual acuity and greater areas of hemorrhage have reported substantial improvements in visual acuity with anti-VEGF treatment. 13–17

Eyes with predominantly hemorrhagic AMD lesions were enrolled in the CATT trial. Hemorrhage as a lesion component was retinal, subretinal or sub-RPE in location. Response to treatment was demonstrated with elimination of associated hemorrhage, reduction in lesion size, and reduction of retinal thickness over the first year. This resulted in a mean improvement of 9.3 letters. All positive changes were maintained over the second year. Eyes like those enrolled in CATT with exudative AMD lesions composed of >50% blood can be managed clinically in a similar manner as those with no or less blood and can be expected to have a similar improvement in visual outcome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by cooperative agreements U10 EY017823, U10 EY017825, U10 EY017826, and U10 EY017828 from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

A listing of the CATT Research Group is in the Appendix

This article contains additional online-only material. The following should appear online-only: Table 4.

None of the authors has any proprietary/financial interest to disclose.

ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT00593450.

Presented in part at the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Meeting. Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, May 8, 2013.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could a3ect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bennett SR, Folk JC, Blodi CF, Klugman M. Factors prognostic of visual outcome in patients with subretinal hemorrhage. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;109:33–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75575-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avery RL, Fekrat S, Hawkins BS, Bressler NM. Natural history of subfoveal subretinal hemorrhage in age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 1996;16:183–9. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199616030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scupola A, Coscas G, Soubrane G, Balestrazzi E. Natural history of macular subretinal hemorrhage in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmologica. 1999;213:97–102. doi: 10.1159/000027400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Submacular Surgery Trials (SST) Research Group. Surgery for hemorrhagic choroidal neovascular lesions of age-related macular degeneration: ophthalmic findings. SST report no. 13. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1993–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizutani T, Yasukawa T, Ito Y, et al. Pneumatic displacement of submacular hemorrhage with or without tissue plasminogen activator. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:1153–7. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1649-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CY, Hooper C, Chiu D, et al. Management of submacular hemorrhage with intravitreal injection of tissue plasminogen activator and expansile gas. Retina. 2007;27:321–8. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000237586.48231.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Handwerger BA, Blodi BA, Chandra SR, et al. Treatment of submacular hemorrhage with low-dose intravitreal tissue plasminogen activator injection and pneumatic displacement. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treatment of Age-related Macular Degeneration with Photodynamic Therapy (TAP) Study Group. Photodynamic therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration with verteporfin: one-year results of 2 randomized clinical trials--TAP report 1. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1329–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gragoudas ES, Adamis AP, Cunningham ET, Jr, et al. VEGF Inhibition Study in Ocular Neovascularization Clinical Trial Group. Pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2805–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al. MARINA Study Group. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1419–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, et al. ANCHOR Study Group. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1432–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heier JS, Brown DM, Chong V, et al. VIEW 1 and VIEW 2 Study Groups. Intravitreal aflibercept (VEGF Trap-Eye) in wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2537–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang MA, Do DV, Bressler SB, et al. Prospective one-year study of ranibizumab for predominantly hemorrhagic choroidal neovascular lesions in age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2010;30:1171–6. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181dd6d8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shienbaum G, Garcia Filho CA, Flynn HW, Jr, et al. Management of submacular hemorrhage secondary to neovascular age-related macular degeneration with anti–vascular endothelial growth factor monotherapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155:1009–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stifter E, Michels S, Prager F, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration with large submacular hemorrhage. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:886–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iacono P, Parodi MB, Introini U, et al. Intravitreal ranibizumab for choroidal neovascularization with large submacular hemorrhage in age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2014;34:281–7. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182979e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JH, Chang YS, Kim JW, et al. Intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for submacular hemorrhage from choroidal neovascularization. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:926–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CATT Research Group. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1897–908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT) Research Group, . Martin DF, Maguire MG, Fine SL, et al. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1388–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grunwald JE, Daniel E, Ying GS, et al. CATT Research Group. Photographic assessment of baseline fundus morphologic features in the Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1634–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeCroos FC, Toth CA, Stinnett SS, et al. CATT Research Group. Optical coherence tomography grading reproducibility during the Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2549–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glatt H, Machemer R. Experimental subretinal hemorrhage in rabbits. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;94:762–73. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(82)90301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toth CA, Morse LS, Hjelmeland LM, et al. Fibrin directs early retinal damage after experimental subretinal hemorrhage. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:723–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080050139046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhisitkul RB, Winn BJ, Lee OT, et al. Neuroprotective effect of intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide against photoreceptor apoptosis in a rabbit model of subretinal hemorrhage. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4071–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arias L, Monés J. Transconjunctival sutureless vitrectomy with tissue plasminogen activator, gas and intravitreal bevacizumab in the management of predominantly hemorrhagic age-related macular degeneration. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:67–72. doi: 10.2147/opth.s8635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skaf AR, Mahmoud T. Surgical treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Semin Ophthalmol. 2011;26:181–91. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2011.577133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayer WJ, Hakim I, Haritoglou C, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and gas versus bevacizumab and gas for subretinal haemorrhage. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91:274–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Treumer F, Roider J, Hillenkamp J. Long-term outcome of subretinal coapplication of rtPA and bevacizumab followed by repeated intravitreal anti-VEGF injections for neovascular AMD with submacular haemorrhage. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:708–13. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuhli-Hattenbach C, Fischer IB, Schalnus R, Hattenbach LO. Subretinal hemorrhages associated with age-related macular degeneration in patients receiving anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:316–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tilanus MA, Vaandrager W, Cuypers MH, et al. Relationship between anticoagulant medication and massive intraocular hemorrhage in age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2000;238:482–5. doi: 10.1007/pl00007887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hwang JC, Del Priore LV, Freund KB, et al. Development of subretinal fibrosis after anti-VEGF treatment in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2011;42:6–11. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20100924-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varshney N, Jain A, Chan V, et al. Anti-VEGF response in macular hemorrhage and incidence of retinal pigment epithelial tears. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48:210–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan CK, Meyer CH, Gross JG, et al. Retinal pigment epithelial tears after intravitreal bevacizumab injection for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2007;27:541–51. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3180cc2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan CK, Abraham P, Meyer CH, et al. Optical coherence tomography-measured pigment epithelial detachment height as a predictor for retinal pigment epithelial tears associated with intravitreal bevacizumab injections. Retina. 2010;30:203–11. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181babda5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carvounis PE, Kopel AC, Benz MS. Retinal pigment epithelium tears following ranibizumab for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:504–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cunningham ET, Jr, Feiner L, Chung C, et al. Incidence of retinal pigment epithelial tears after intravitreal ranibizumab injection for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2447–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarraf D, Chan C, Rahimy E, Abraham P. Prospective evaluation of the incidence and risk factors for the development of RPE tears after high- and low-dose ranibizumab therapy. Retina. 2013;33:1551–7. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31828992f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ying GS, Huang J, Maguire MG, et al. Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials Research Group. Baseline predictors for one-year visual outcomes with ranibizumab or bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:122–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Todorich B, Scott IU, Flynn HW, Jr, Johnson MW. Evolving strategies in the management of submacular hemorrhage associated with choroidal neovascularization in the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor era. Retina. 2011;31:1749–52. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31821504df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.